Abstract

Compared to the broad palette of fluorescent molecules, there are relatively few structures that are competent to support bioluminescence. Here we focus on recent advances in the development of luminogenic substrates for firefly luciferase. The scope of this light-emitting chemistry has been found to extend well beyond the natural substrate, and to include enzymes incapable of luciferase activity with D-luciferin. The broadening range of luciferin analogues and evolving insight into the bioluminescent reaction offer new opportunities for the construction of powerful optical reporters of use in live cells and animals.

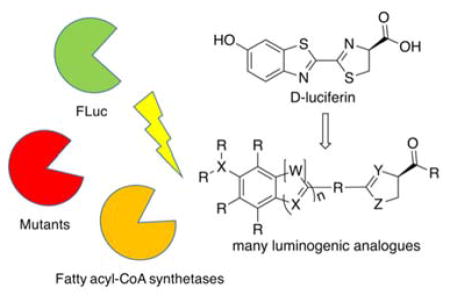

Graphical abstract

Main Text

The essential features of fluorescent molecules are generally well known, with numerous examples spanning the range from the ultraviolet to the near-infrared.1 Less well established is the scope of bioluminescence, and the critical features required for luciferase substrates. Early on, one pressing question piqued our curiosity: why are there so few luciferins?

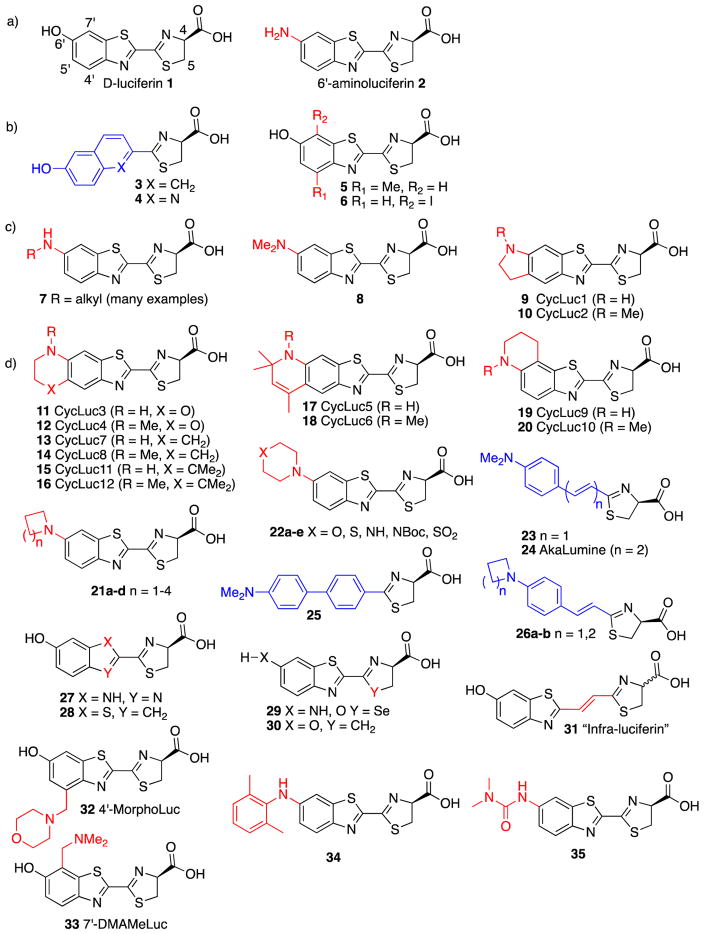

Luminous luciferins

The only natural substrate for bioluminescent fireflies is D-luciferin (Figure 1a; 1). Over fifty years ago, it was discovered that 6′-aminoluciferin (2), containing a conservative amino replacement for D-luciferin’s hydroxyl electron donor, is also a bright luminogenic substrate.2,3 On the other hand, installation of a 6′-acetamide prevents light emission, and acts as a weak inhibitor. A dearth of emissive luciferin analogues remained for many years until Branchini et al. synthesized analogues 3 and 4 that replaced the benzothiazole ring rather than the hydroxyl donor, and found that these molecules are capable of luminescence at elevated pH (Figure 1b).4 Although some conservative changes to D-luciferin were reported to be capable of light emission – such as methylation at the 4′-position (5)5 and iodination of the 7′-position (6)6 – others such as 5,5-dimethylation essentially prevent activity.7 The overall impression was that relatively few changes to D-luciferin could be tolerated. But that impression proved to be inaccurate.

Figure 1.

Structures of luminogenic firefly luciferin analogues reported in the literature: a) before 1989; b) from 1989–2004; c) from 2008–2011; d) from 2012–2017. Red = modification to luciferin scaffold; blue = replacement of core luciferin scaffold.

Several years ago, it was found that the 6′-donor can be replaced with a variety of alkylamines (Figure 1c).8–10 This includes mono-alkylated amines (7),8–10 dialkylated amines (8),9,10 and 5′,6′-fused cyclic alkylamines (9, 10).9 The behavior of these analogues differs from that of D-luciferin in several respects. First, the apparent Km values are lower. Second, the sustained bioluminescence signal is weaker in vitro with purified firefly luciferase, due in part to product inhibition. Third, the emission wavelengths are red-shifted as the electron-donating ability increases from an unalkylated 6′-amine to a monoalkylated and then dialkylated amine.9 In vitro, the net effect is somewhat disappointing – although the peak wavelength is shifted, the total red-shifted light is reduced after an initial flash of light. However, in live cells and living organisms, the low Km and higher lipophilicity of aminoluciferin analogues can yield substantial advantages over D-luciferin, enabling bright bioluminescence at much lower substrate doses.11–13 Furthermore, mutation of the luciferase can reduce product inhibition and achieve high selectivity for alkylamino luciferins over D-luciferin.11,13,14

Firefly luciferase has now been revealed to be remarkably promiscuous, accepting an impressively broad range of analogues with alkylamine donors (Figure 1).3 Bulky and rigid alkylamine analogues are accepted (7; 11–20),13,15 as well as cyclic secondary amine donors (21–22).16,17 Styrenyl luciferins with a dimethylamine donor are relatively bright emitters despite their lack of a benzothiazole (23–24),18 whereas the corresponding biphenyl analogues are weakly luminescent (25).19 Extending the alkene conjugation is well tolerated and can shift emission into the near-IR, with advantages for in vivo imaging (24).20 Furthermore, cyclic secondary amine donors are tolerated in styrenyl luciferins (26), suggesting that many of the alkylamine donors reported for the canonical benzothiazole scaffold could be transferrable to the styrenyl scaffold.21 A wide variety of alkylated aminoluciferins are also bright emitters in live cells and mice, offering the ability to further refine and tune their photophysical and pharmacokinetic properties.13,14,22,23

In analogues where the 6′-hydroxyl is retained, the core benzothiazole has been substituted with different heterocycles such as benzimidazole (27)24 and thiophene (28),25 albeit with a loss in luminescence activity (Figure 1d). The sulfur in the thiazoline ring can be replaced with selenium (29).26 Thiazoline replacement with a pyrroline is also tolerated (30), whereas oxazoline and other amino acid-derived analogues are not.27 Insertion of a double bond between the benzothiazole and thiazoline ring impressively red-shifts emission, but lowers photon flux (31).28 Halogenation of D-luciferin 1 with fluorine,29,30 chlorine,29 and bromine31 is generally well tolerated, as is alkylation at the 5′ position,29,32 although bromine is disruptive in the 7′ and especially 4′ positions for photophysical and/or steric reasons. Indeed, bulky modifications on the 4′ and 7′ positions (32–33) can engender selectivity for mutant luciferases.33

To further probe the scope of permissible donors in the 6′-position of D-luciferin, we recently developed a new route to their synthesis that allows access to disparate derivatives, revealing some surprises.17 As expected, analogues conforming to the general structure 7 with donors such as allylamine and trifluoroethylamine are luminogenic, as are cyclic secondary amine donors ranging from azetidine to piperazine to thiomorpholine (21–22).17 On the other hand, the thiomorpholine dioxide analogue 22e is very weakly emissive, suggesting a limit to the promiscuity of firefly luciferase. Arylamine derivatives, previously undescribed, were mostly found to be non-emissive inhibitors, in line with expectations based on the low quantum yields of arylamine-containing fluorophores. However, some rotationally-restricted ortho-substituted arylamines such as 34 can be weak luminogenic substrates, and mutation of the luciferase can further improve this activity.17 Analogues incorporating sulfoxide and sulfone groups in the 6′ position are non-emissive as expected, but so is the 6′-thiomethyl derivative, even though it is fluorescent.17 Classic “caged” derivatives, such as 6′-amides and carbamates, are widely considered to be non-emissive until unmasked to the amine. While this generally held true among the new analogues synthesized, the dimethylurea 35 was capable of weak bioluminescence.

Since bioluminescence emission occurs from within the luciferase active site, its molecular features (e.g., size, polarity) may limit emission from some potentially chemiluminescent analogues. On the other hand, it could also extend the range of emitters beyond what might otherwise be expected in solution (e.g., through rotational restriction). We anticipate that many of these features can be tuned by mutagenesis to further broaden the scope and selectivity of luminogenic substrates.11,33,34 Furthermore, both emissive and non-emissive analogues have value for the design of turn-ON or turn-OFF luminescent sensors, and the increasing variety of luminogenic scaffolds offer new strategies for their construction.17,35 One can thus expect many more luciferin analogues and luciferin-based probes to be reported in the coming years, with useful properties for selective imaging in live cells, tissues, and animals.

Latent luciferases

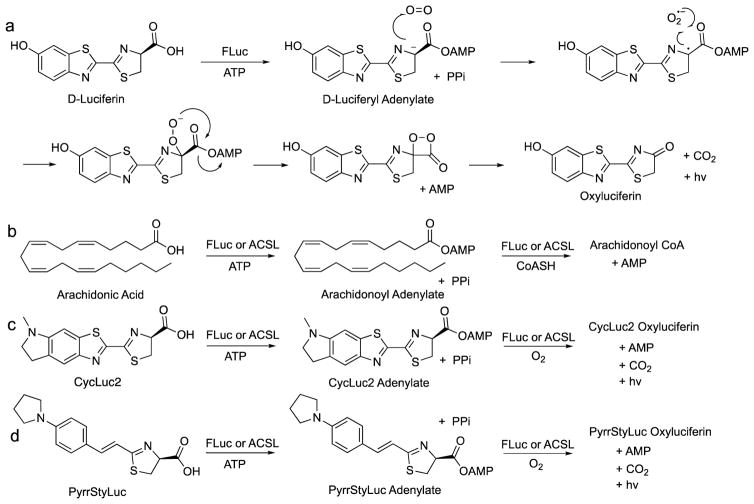

Beetle luciferases are thought to have evolved from long-chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSLs).36 The work of Oba and coworkers has shown that insect ACSLs with high homology to firefly luciferase lack luciferase activity with D-luciferin.37–39 This begged the question: why? These enzymes are all promiscuous with respect to their fatty acid substrates. The inherent chemistry of luciferin analogues should allow light emission if the substrate can be adenylated by the enzyme (Figure 2). Although ACSLs such as the fruit fly enzyme CG6178 (39% identity) cannot adenylate D-luciferin and lack luciferase activity, CG6178 was recently revealed to be a latent luciferase that emits light with CycLuc2 (Figure 2).40 In this respect, it is more selective than firefly luciferase. Presumably, the bulk and/or rigidity of the 5′,6′-fused ring is important to properly align the substrate for adenylation, which then allows the mostly substrate-directed light emission chemistry to proceed. Adenylation stabilizes C4 deprotonation, allowing single electron transfer to oxygen to form a luciferin radical and superoxide.40,41 Recombination to the peroxide followed by cyclization to the transient dioxetanone and subsequent decarboxylation are then thought to lead to an excited-state oxyluciferin.

Figure 2.

Firefly luciferase (FLuc) can accept a broad range of substrates, whereas homologous long-chain fatty-acyl CoA synthetases (ACSLs) are more selective. a) FLuc, but not ACSLs, can adenylate D-luciferin, which then reacts with oxygen to generate an excited-state oxyluciferin; b) Adenylation of fatty acids by FLuc or ACSLs results in the formation of fatty acyl-CoAs; c) CycLuc2 is a luminogenic substrate for FLuc and the ACSLs CG6178 and AbLL; d) PyrrStyLuc is a luminogenic substrate for FLuc and AbLL, but not CG6178.

Further profiling with a larger palette of luciferin analogues has since revealed that CG6178 has latent luciferase activity with several substrates, particularly rigid dialkylated CycLucs (Figure 1).21 Moreover, a second latent luciferase has been identified in AbLL, an ACSL from the nonluminescent beetle Agrypnus binodulus.21 Although generally a weaker luciferase than CG6178, it has a distinct substrate fingerprint. In particular, it emits light with styrenyl luciferin analogues that are non-emissive with CG6178 (Figure 2d).

Fatty acyl-CoA synthetases have lessons to teach us about how luciferase activity developed, and which features influence substrate selectivity. In addition to the latent luciferase activity of CG6178 and AbLL, weak activity of an ACSL with D-luciferin has been reported,42 and mutation of ACSLs can reveal nascent luciferase activity with D-luciferin.43 Furthermore, a chimera between firefly luciferase and CG6178 can be a functional luciferase,44 and chimeras between beetle luciferases can have high activity.45,46 On the other hand, an ACSL from the beetle Pyrophorus angustus failed to demonstrate any luciferase activity despite its higher homology to beetle luciferases than CG6178 or AbLL.21 Potentially, chimeras between luciferases and ACSLs could also be used to modulate activity and substrate preference and to better understand the molecular basis for these effects.

There is reason to suspect that the scope of bioluminescence could even extend outside the family of ACSLs. Recently, an earthworm luciferase has been discovered that involves adenylation of a structurally distinct luciferin as a critical step, likely operating through a similar general oxidation mechanism as firefly luciferase.47 This suggests that a broader range of adenylating enzymes could be latent luciferases, capable of bioluminescence if plied with the appropriate substrate.

Lessons learned

Based on the ability of luciferin analogues to serve as substrates for ACSLs (including firefly luciferase itself), these molecules could be considered to be acting as fatty acid mimics. At the very least, they bind in a substrate pocket which also accepts fatty acids, and with a similar orientation of the carboxylate group, enabling subsequent adenylation (Figure 2).

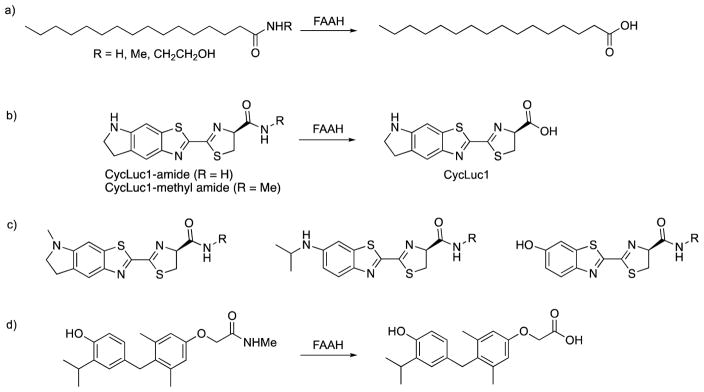

Most luciferin-based reporters generally treat luciferin as a leaving group, and do not take advantage of its inherent molecular properties as a basis for recognition.3,48 We considered that luciferins might be well-positioned to act as reporters for enzymes that release free fatty acids. To test this idea, we made luciferin amides (Figure 3), which we hypothesized would be substrates for the enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH).22 Lacking a carboxylate, these analogues are unable to be adenylated and hence unable to emit light. Hydrolysis of the amide unmasks the critical carboxylate, releasing the luminogenic luciferin, thus reporting on the liberating hydrolytic activity (Figure 3). FAAH selectively hydrolyzes primary amides and small secondary amides (e.g., methylamide, ethanolamide). These luciferin amides are poorly cleaved, if at all, by other cellular enzymes, as no bioluminescence emission is seen in luciferase-expressing cells which lack FAAH. However, strong bioluminescence emission is seen in cells transfected with FAAH, and endogenous FAAH activity is sufficient to unmask the luciferin.22

Figure 3.

Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) will accept a range of substrates. This includes endogenous and synthetic fatty acid amides (a), luciferin amides (b, c), and amides of the thyromimetic, sobetirome (d).

Typically, when luciferin-based probes have been utilized in transgenic mice that ubiquitously express firefly luciferase, they give a modest signal to noise ratio. There is often considerable background from the probe itself, trace impurities in the probe, and/or basal cleavage (not necessarily by the desired target).3 FAAH is highly expressed in the brain, but the tissue depth, location under the skull, and blood-brain barrier all render the brain one of the most difficult tissues to image. Remarkably, when luciferin amides are introduced into ubiquitously-expressing luciferase mice, the brightest signal is from the brain.22 Inhibitors of FAAH block this bioluminescence, and a FAAH inhibitor that can cross the blood-brain barrier can be readily distinguished from one that does not.

Part of the reason for this success is the improved ability of luciferin amides to access brain tissue over their parent luciferins. Neutral luciferin amides can act as “prodrugs” for delivering the anionic luciferin into the brain at very low substrate doses.22,49 Alkylamino luciferin amides are superior to their parent substrates for imaging wild-type and mutant luciferases in the brain.14,22 Bright bioluminescence can be observed even at doses 1000-fold lower than the standard imaging conditions with D-luciferin, as well as with mutant luciferases that are undetectable with D-luciferin.14

The propensity for FAAH to cleave fatty acid and luciferin amides could potentially be extended more broadly for the delivery of carboxylate-containing drugs into the brain.49 Indeed, recent work has shown that amides of the thyromimetic sobetirome are substrates for FAAH and greatly improve brain delivery over the parent carboxylate, whereas the corresponding esters do not (Figure 3).50

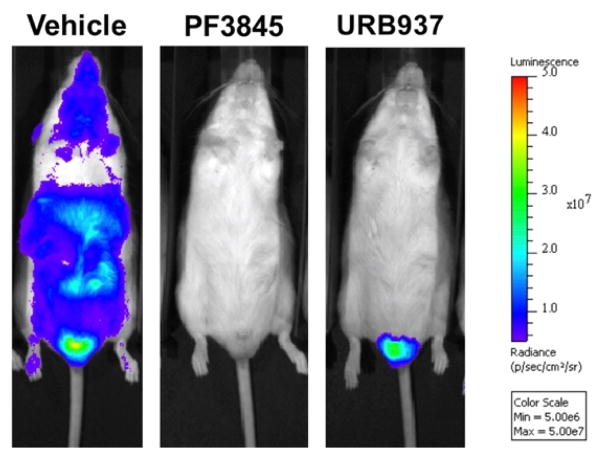

It should be noted that the published work on luciferin amides described the imaging of female mice.22 When male mice were imaged under the same conditions, conspicuously bright bioluminescence was also observed in the testes, consistent with the strong FAAH expression in this organ (Figure 4).51 Pre-incubation with the specific FAAH inhibitor PF3845 blocked FAAH activity (and hence luciferin amide bioluminescence) in all tissues, including the testes (Figure 4). Interestingly, the FAAH inhibitor URB937, which cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, failed to block bioluminescence from luciferin amides in the testes as well. Like the brain, the testis restricts access of many small molecules.52 Though morphologically distinct, both blood-tissue barriers express the efflux pumps Abcg2 and Abcb1, which are known to exclude URB937.53 Luciferin amides thus have potential for bioluminescence imaging of events and activities specific to the testes, and this amide-based prodrug approach could enable FAAH-mediated compound delivery into the testes as well as the brain.

Figure 4.

Ventral view of male ubiquitously-expressing transgenic luciferase mice imaged with CycLuc1-amide after treatment with vehicle control or the indicated FAAH inhibitor as in ref 22.

Could luciferin esters have similar utility to amides as selective probes in cells and in vivo? D-luciferin methyl ester was first reported to be a carboxyesterase substrate by Miska and Geiger in 1987.54,55 Several luciferin esters have been used to deliver luciferins into live cells and mice,22,28,56 but the location and identity of the enzyme(s) responsible for their hydrolysis has not been unambiguously assigned. Recently, D-luciferin methyl ester was reported to be a highly selective sensor for human carboxyesterase 1 (CES1).57 However, a CES1 inhibitor had little effect on the bioluminescence from live luciferase-expressing cells. CES1 is also primarily expressed in the liver, and relatively poorly expressed in cell types from many other tissues.58 It thus seems likely that luciferin esters can be substrates for several hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., lipases) in addition to CES1. Indeed, some luciferin esters are also (nonexclusive) substrates for FAAH.22 As the number and variety of luciferin scaffolds grows, there will be increasing opportunities to take advantage of their structural diversity for the design of new luminogenic sensors.17,35,59 Potentially, judicious modification of the ever-expanding armada of luciferin analogues could allow one to tune the selectivity of luciferin esters to report on a restricted subset of hydrolases.

Conclusion

Basic studies into firefly luciferase and its substrate have revealed that the chemistry of bioluminescence extends to wide range of luciferin analogues, and even includes adenylating enzymes that lack luciferase activity with D-luciferin. This expanding intersection between the chemistry of luciferins and the biology of luciferases is expected to reveal additional surprises, illuminating insights, and sensitive new detection methods of broad and general utility.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (EB013270, DA039961, and EB020243) and the McKnight Foundation. S.T.A. was supported by F31GM016586.

References

- 1.Lavis LD, Raines RT. Bright building blocks for chemical biology. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:855–866. doi: 10.1021/cb500078u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White EH, Worther H, Seliger HH, McElroy WD. Amino Analogs of Firefly Luciferin and Biological Activity Thereof. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:2015–2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams ST, Miller SC. Beyond D-luciferin: expanding the scope of bioluminescence imaging in vivo. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;21:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branchini BR, Hayward MM, Bamford S, Brennan PM, Lajiness EJ. Naphthyl- and quinolylluciferin: green and red light emitting firefly luciferin analogues. Photochem Photobiol. 1989;49:689–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1989.tb08442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farace C, Blanchot B, Champiat D, Couble P, Declercq G, Millet JL. Synthesis and characterization of a new substrate of Photinus pyralis luciferase: 4-methyl-D-luciferin. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem Z Klin Chem Klin Biochem. 1990;28:471–474. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1990.28.7.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SY, Choe YS, Lee KH, Lee J, Choi Y, Kim BT. Synthesis of 7′-[123I]iodo-D-luciferin for in vivo studies of firefly luciferase gene expression. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1161–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branchini BR, Murtiashaw MH, Magyar RA, Portier NC, Ruggiero MC, Stroh JG. Yellow-green and red firefly bioluminescence from 5,5-dimethyloxyluciferin. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2112–2113. doi: 10.1021/ja017400m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodroofe CC, Shultz JW, Wood MG, Osterman J, Cali JJ, Daily WJ, Meisenheimer PL, Klaubert DH. N-Alkylated 6′-aminoluciferins are bioluminescent substrates for Ultra-Glo and QuantiLum luciferase: new potential scaffolds for bioluminescent assays. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10383–10393. doi: 10.1021/bi800505u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy GR, Thompson WC, Miller SC. Robust light emission from cyclic alkylaminoluciferin substrates for firefly luciferase. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13586–13587. doi: 10.1021/ja104525m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takakura H, Kojima R, Urano Y, Terai T, Hanaoka K, Nagano T. Aminoluciferins as functional bioluminogenic substrates of firefly luciferase. Chem Asian J. 2011;6:1800–1810. doi: 10.1002/asia.201000873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harwood KR, Mofford DM, Reddy GR, Miller SC. Identification of mutant firefly luciferases that efficiently utilize aminoluciferins. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1649–1657. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans MS, Chaurette JP, Adams ST, Jr, Reddy GR, Paley MA, Aronin N, Prescher JA, Miller SC. A synthetic luciferin improves bioluminescence imaging in live mice. Nat Methods. 2014;11:393–395. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mofford DM, Reddy GR, Miller SC. Aminoluciferins Extend Firefly Luciferase Bioluminescence into the Near-Infrared and Can Be Preferred Substrates over d-Luciferin. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:13277–13282. doi: 10.1021/ja505795s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams ST, Mofford DM, Reddy GSKK, Miller SC. Firefly Luciferase Mutants Allow Substrate-Selective Bioluminescence Imaging in the Mouse Brain. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:4943–4946. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kojima R, Takakura H, Ozawa T, Tada Y, Nagano T, Urano Y. Rational design and development of near-infrared-emitting firefly luciferins available in vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:1175–1179. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakiuchi M, Ito S, Kiyama M, Goto F, Matsuhashi T, Yamaji M, Maki S, Hirano T. Electronic and Steric Effects of Cyclic Amino Substituents of Luciferin Analogues on a Firefly Luciferin–Luciferase Reaction. Chem Lett. 2017;46:1090–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma DK, Adams ST, Liebmann KL, Miller SC. Rapid Access to a Broad Range of 6′-Substituted Firefly Luciferin Analogues Reveals Surprising Emitters and Inhibitors. Org Lett. 2017;19:5836–5839. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwano S, Obata R, Miura C, Kiyama M, Hama K, Nakamura M, Amano Y, Kojima S, Hirano T, Maki S, Niwa H. Development of simple firefly luciferin analogs emitting blue, green, red, and near-infrared biological window light. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:3847–3856. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miura C, Kiyama M, Iwano S, Ito K, Obata R, Hirano T, Maki S, Niwa H. Synthesis and luminescence properties of biphenyl-type firefly luciferin analogs with a new, near-infrared light-emitting bioluminophore. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:9726–9734. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuchimaru T, Iwano S, Kiyama M, Mitsumata S, Kadonosono T, Niwa H, Maki S, Kizaka-Kondoh S. A luciferin analogue generating near-infrared bioluminescence achieves highly sensitive deep-tissue imaging. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11856. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mofford DM, Liebmann KL, Sankaran GS, Reddy GSKK, Reddy GR, Miller SC. Luciferase Activity of Insect Fatty Acyl-CoA Synthetases with Synthetic Luciferins. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:2946–2951. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mofford DM, Adams ST, Reddy GSKK, Reddy GR, Miller SC. Luciferin Amides Enable in Vivo Bioluminescence Detection of Endogenous Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase Activity. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:8684–8687. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu W, Su J, Tang C, Bai H, Ma Z, Zhang T, Yuan Z, Li Z, Zhou W, Zhang H, Liu Z, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Du L, Gu L, Li M. cybLuc: An Effective Aminoluciferin Derivative for Deep Bioluminescence Imaging. Anal Chem. 2017;89:4808–4816. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCutcheon DC, Paley MA, Steinhardt RC, Prescher JA. Expedient synthesis of electronically modified luciferins for bioluminescence imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7604–7607. doi: 10.1021/ja301493d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woodroofe CC, Meisenheimer PL, Klaubert DH, Kovic Y, Rosenberg JC, Behney CE, Southworth TL, Branchini BR. Novel heterocyclic analogues of firefly luciferin. Biochemistry. 2012;51:9807–9813. doi: 10.1021/bi301411d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conley NR, Dragulescu-Andrasi A, Rao J, Moerner WE. A Selenium Analogue of Firefly D-Luciferin with Red-Shifted Bioluminescence Emission. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:3350–3353. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ioka S, Saitoh T, Iwano S, Suzuki K, Maki SA, Miyawaki A, Imoto M, Nishiyama S. Synthesis of Firefly Luciferin Analogues and Evaluation of the Luminescent Properties. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:9330–9337. doi: 10.1002/chem.201600278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jathoul AP, Grounds H, Anderson JC, Pule MA. A dual-color far-red to near-infrared firefly luciferin analogue designed for multiparametric bioluminescence imaging. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:13059–13063. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takakura H, Kojima R, Ozawa T, Nagano T, Urano Y. Development of 5′- and 7′-substituted luciferin analogues as acid-tolerant substrates of firefly luciferase. Chembiochem. 2012;13:1424–1427. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pirrung MC, Biswas G, De Howitt N, Liao J. Synthesis and bioluminescence of difluoroluciferin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:4881–4883. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinhardt RC, Rathbun CM, Krull BT, Yu JM, Yang Y, Nguyen BD, Kwon J, McCutcheon DC, Jones KA, Furche F, Prescher JA. Brominated Luciferins Are Versatile Bioluminescent Probes. Chembiochem. 2017;18:96–100. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinhardt RC, O’Neill JM, Rathbun CM, McCutcheon DC, Paley MA, Prescher JA. Design and Synthesis of an Alkynyl Luciferin Analogue for Bioluminescence Imaging. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:3671–3675. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones KA, Porterfield WB, Rathbun CM, McCutcheon DC, Paley MA, Prescher JA. Orthogonal Luciferase-Luciferin Pairs for Bioluminescence Imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:2351–2358. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halliwell LM, Jathoul AP, Bate JP, Worthy HL, Anderson JC, Jones DD, Murray JAH. ΔFlucs: Brighter Photinus pyralis firefly luciferases identified by surveying consecutive single amino acid deletion mutations in a thermostable variant. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2017;115:50–59. doi: 10.1002/bit.26451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takakura H, Kojima R, Kamiya M, Kobayashi E, Komatsu T, Ueno T, Terai T, Hanaoka K, Nagano T, Urano Y. New Class of Bioluminogenic Probe Based on Bioluminescent Enzyme-Induced Electron Transfer: BioLeT. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:4010–4013. doi: 10.1021/ja511014w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oba Y, Ojika M, Inouye S. Firefly luciferase is a bifunctional enzyme: ATP-dependent monooxygenase and a long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase. FEBS Lett. 2003;540:251–254. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oba Y, Ojika M, Inouye S. Characterization of CG6178 gene product with high sequence similarity to firefly luciferase in Drosophila melanogaster. Gene. 2004;329:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oba Y, Sato M, Inouye S. Cloning and characterization of the homologous genes of firefly luciferase in the mealworm beetle, Tenebrio molitor. Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15:293–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oba Y, Iida K, Ojika M, Inouye S. Orthologous gene of beetle luciferase in non-luminous click beetle, Agrypnus binodulus (Elateridae), encodes a fatty acyl-CoA synthetase. Gene. 2008;407:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mofford DM, Reddy GR, Miller SC. Latent luciferase activity in the fruit fly revealed by a synthetic luciferin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:4443–4448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319300111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Branchini BR, Behney CE, Southworth TL, Fontaine DM, Gulick AM, Vinyard DJ, Brudvig GW. Experimental Support for a Single Electron-Transfer Oxidation Mechanism in Firefly Bioluminescence. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:7592–7595. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viviani VR, Prado RA, Neves DR, Kato D, Barbosa JA. A route from darkness to light: emergence and evolution of luciferase activity in AMP-CoA-ligases inferred from a mealworm luciferase-like enzyme. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3963–3973. doi: 10.1021/bi400141u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oba Y, Iida K, Inouye S. Functional conversion of fatty acyl-CoA synthetase to firefly luciferase by site-directed mutagenesis: A key substitution responsible for luminescence activity. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2004–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oba Y, Tanaka K, Inouye S. Catalytic properties of domain-exchanged chimeric proteins between firefly luciferase and Drosophila fatty Acyl-CoA synthetase CG6178. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:2739–2744. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Branchini BR, Southworth TL, Fontaine DM, Davis AL, Behney CE, Murtiashaw MH. A Photinus pyralis and Luciola italica Chimeric Firefly Luciferase Produces Enhanced Bioluminescence. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6287–6289. doi: 10.1021/bi501202u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Branchini BR, Southworth TL, Fontaine DM, Kohrt D, Welcome FS, Florentine CM, Henricks ER, DeBartolo DB, Michelini E, Cevenini L, Roda A, Grossel MJ. Red-emitting chimeric firefly luciferase for in vivo imaging in low ATP cellular environments. Anal Biochem. 2017;534:36–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsarkova AS, Kaskova ZM, Yampolsky IV. A Tale Of Two Luciferins: Fungal and Earthworm New Bioluminescent Systems. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:2372–2380. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heffern MC, Park HM, Au-Yeung HY, Van de Bittner GC, Ackerman CM, Stahl A, Chang CJ. In vivo bioluminescence imaging reveals copper deficiency in a murine model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:14219–14224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613628113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mofford DM, Miller SC. Luciferins Behave Like Drugs. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2015;6:1273–1275. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meinig JM, Ferrara SJ, Banerji T, Banerji T, Sanford-Crane HS, Bourdette D, Scanlan TS. Targeting Fatty-Acid Amide Hydrolase with Prodrugs for CNS-Selective Therapy. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8:2468–2476. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long JZ, LaCava M, Jin X, Cravatt BF. An anatomical and temporal portrait of physiological substrates for fatty acid amide hydrolase. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:337–344. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M012153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Enokizono J, Kusuhara H, Ose A, Schinkel AH, Sugiyama Y. Quantitative investigation of the role of breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp/Abcg2) in limiting brain and testis penetration of xenobiotic compounds. Drug Metab Dispos Biol Fate Chem. 2008;36:995–1002. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moreno-Sanz G, Barrera B, Armirotti A, Bertozzi SM, Scarpelli R, Bandiera T, Prieto JG, Duranti A, Tarzia G, Merino G, Piomelli D. Structural determinants of peripheral O-arylcarbamate FAAH inhibitors render them dual substrates for Abcb1 and Abcg2 and restrict their access to the brain. Pharmacol Res. 2014;87:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miska W, Geiger R. Synthesis and characterization of luciferin derivatives for use in bioluminescence enhanced enzyme immunoassays. New ultrasensitive detection systems for enzyme immunoassays, I. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem Z Für Klin Chem Klin Biochem. 1987;25:23–30. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1987.25.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miska W, Geiger R. A new type of ultrasensitive bioluminogenic enzyme substrates. I Enzyme substrates with D-luciferin as leaving group. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1988;369:407–411. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1988.369.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Craig FF, Simmonds AC, Watmore D, McCapra F, White MR. Membrane-permeable luciferin esters for assay of firefly luciferase in live intact cells. Biochem J. 1991;276(Pt 3):637–641. doi: 10.1042/bj2760637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang DD, Jin Q, Zou LW, Hou J, Lv X, Lei W, Cheng HL, Ge GB, Yang L. A bioluminescent sensor for highly selective and sensitive detection of human carboxylesterase 1 in complex biological samples. Chem Commun. 2016;52:3183–3186. doi: 10.1039/c5cc09874b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun X, Ai M, Wang Y, Shen S, Gu Y, Jin Y, Zhou Z, Long Y, Yu Q. Selective Induction of Tumor Cell Apoptosis by a Novel P450-mediated Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Inducer Methyl 3-(4-Nitrophenyl) Propiolate. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:8826–8837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.429316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ioka S, Saitoh T, Maki SA, Imoto M, Nishiyama S. Development of a luminescence-controllable firefly luciferin analogue using selective enzymatic cyclization. Tetrahedron. 2016;72:7505–7508. [Google Scholar]