Abstract

Empowering consumers to be active decision-makers in their own care is a core tenet of personalized, or precision medicine. Nonetheless, there is a dearth of research on intervention preferences in families seeking interventions for a child with behavior problems. Specifically, the evidence is inconclusive as to whether providing parents with choice of intervention improves child/youth outcomes (i.e., reduces externalizing problems). In this study, 129 families presenting to community mental health clinics for child conduct problems were enrolled in a doubly randomized preference study and initially randomized to choice or no-choice conditions. Families assigned to the choice condition were offered their choice of intervention from among three different formats of the Parent Management Training-Oregon Model/PMTO (group, individual clinic, home based) and services-as-usual (child-focused therapy). Those assigned to the no-choice condition were again randomized, to one of the four intervention conditions. Intent-to-treat analyses revealed partial support for the effect of parental choice on child intervention outcomes. Assignment to the choice condition predicted teacher-reported improved child hyperactivity/inattention outcomes at 6-months post-treatment completion. No main effect of choice on parent reported child outcomes was found. Moderation analyses indicated that among parents who selected PMTO, teacher report of hyperactivity/inattention was significantly improved compared with parents selecting SAU, and compared with those assigned to PMTO within the no-choice condition. Contrary to hypotheses, teacher report of hyperactivity/inattention was also significantly improved for families assigned to SAU within the no-choice condition, indicating that within the no-choice condition, SAU outperformed the parenting interventions. Implications for prevention research are discussed.

Keywords: PMTO, choice of intervention, parenting, child outcomes

Introduction

Precision, or personalized medicine, provides prevention and treatment interventions tailored to the needs, characteristics, and preferences of individuals (Bierman, Nix, Maples, Murphy, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2006; Ng & Weisz, 2016). Core to precision medicine is the recognition that those receiving services should be involved in decisions about the format, design, and delivery of those services (Collins & Varmus, 2015). However, this relatively newer area of research has focused largely on participant needs and responses to intervention, with a dearth of research aimed at participant choice, or preferences for type, features, or formats of intervention. In this article we report data from a randomized trial aimed at understanding preferences for interventions to address children’s externalizing symptoms.

Child externalizing symptoms (i.e., conduct, oppositional behavior, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems) bring significant risks for later problem behaviors including delinquency, substance use, and academic achievement difficulties (Dalsgaard, Mortensen, Frydenberg, & Thomsen, 2013; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989). These problems also are the most common source of mental health referrals for youth (Briggs-Gowan, Horwitz, Schwab-Stone, Leventhal, & Leaf, 2000). Evidence-based parenting programs are the optimal interventions to reduce child externalizing problems (Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein, & Winslow, 2015) and these programs have robust effects in preventing youth substance use and related difficulties (e.g., Haggerty, Skinner, MacKenzie, & Catalano, 2007).

Most mental health prevention and treatment interventions, however, provide a fixed prescription (i.e., ‘one size fits all’) approach, despite a growing body of evidence that has revealed important contextual moderators of both help-seeking and intervention effectiveness. For example, ethnicity moderated associations between attitudes, stigma, and intentions to seek mental health services in a sample of 238 parents (Turner, Jensen-Doss, & Heffer, 2015). Specifically, positive attitudes were associated with greater intent to seek services in European-, but not African- or Hispanic-Americans, and stigma was linked to less likelihood to seek services only in Hispanic-Americans.

Moreover, children in need of mental health prevention or treatment often do not receive services (Merikangas et al., 2010). This is particularly true among minorities, as well as low-income families; for example, even after accounting for SES and health insurance status, African-Americans still experienced higher unmet service needs than majority groups (Broman, 2012). Participation in prevention programs for child behavior problems has been documented to be as low as 25% among low SES families, compared with 44% among higher-income families (Heinrichs, Bertram, Kuschel, & Hahlweg, 2005). Empowering families by providing them with choices for their children’s interventions (i.e., addressing families’ preferences) may be one way to improve engagement, and, most important, enhance benefit from interventions (Mian, Eisenhower, & Carter, 2015).

Examining Parent Preferences

We use the term preference to refer to intervention elements that individuals like or want (Arnkoff, Glass, & Shapiro, 2002). Several researchers have used discrete choice experiments (DCEs) to understand parental preferences for children’s mental health services (e.g., Cunningham et al., 2008, 2013; Wymbs et al., 2015). For example, Wymbs et al. (2015) examined preferences for children’s ADHD interventions (individual or group) among 445 treatment-seeking parents. Sixty percent preferred individual over group parent training, placing high value on receiving information about their child’s problems. Parents preferring group parent training (20%) valued actively generating solutions for their child’s behavior problems. Studies have examined other attributes salient to parents; for many, treatment outcome appears to be key (Schatz et al., 2015). These studies provided important clues about correlates of parents’ preferences but have not examined revealed preferences—i.e., whether providing parents with intervention choices improves actual engagement – and particularly outcomes.

Preference Study Designs

Participant preferences have typically been studied using three designs: traditional randomized controlled trials/RCTs, partially randomized preference trials (PRPT; Brewin & Bradley, 1989) and doubly randomized preference trials (DRPT; Long, Little, & Lin, 2008; Marcus, Stuart, Wang, Shadish, & Steiner, 2012). A traditional RCT preference design incorporates a question about the participant’s preferred intervention, after which standard randomization takes place. This design does not account for the potential dropout of participants who have strong preferences for a treatment option they are not randomized to, leaving mostly those with weak or no preference in the study. In a PRPT, participants who strongly favor an intervention are offered their choice, while others are randomized; this design thus prevents dropout of those with strong preferences. However, not randomizing individuals with strong preferences is a significant confound, making it hard to attribute differences in engagement or outcomes (e.g., lack of positive outcomes for randomized individuals may be due to poor motivation or desire for change; see, e.g., Torgerson & Sibbald, 1998). DRPTs randomize all participants into a choice or a no-choice condition. Those in the choice condition select their preferred intervention; those assigned to no-choice are again randomized to an intervention. DRPTs allow for the examination of direct effects of choice on intervention engagement and outcome, increasing internal validity (He, Gewirtz, Lee, Morrell, & August, 2016).

Does providing choice of intervention improve outcomes?

Participants who receive their preferred intervention may be more likely to be engaged in and adhere to the program, increasing the likelihood of positive outcomes (Swift, Callahan, & Vollmer, 2011). Street, Elwyn, and Epstein (2012) suggested that providing choices might enhance outcomes by improving attendance and enhancing clients’ autonomy, sense of control and therapeutic alliance. However, results from studies have been inconclusive: some have found that offering choices for treatment improved outcomes (Kocsis et al., 2009), others have found no significant associations between offering choice and improved outcomes (Chilvers et al., 2001; Dobscha, Corson, & Gerrity, 2007; Kwan et al., 2010), and one study found that providing choices was associated with poorer outcomes (Burke et al., 2008). Research design (i.e., type of preference study) appears to act as a moderator in the relationship of choice to outcomes in studies of adults in psychotherapy, with RCTs and DRPTs, (compared with PRPTs) showing the biggest difference in favor of preference matching (Swift et al., 2011). Even among DRPTs, however, results have been mixed, with some studies finding improved outcomes as a function of choice (e.g., Clark et al., 2008; Marcus et al., 2012; McCaffery et al., 2011) and others reporting no differences (Yancy, McVay, & Voils, 2015). Most preference studies, however, have focused on medical treatment. The current study is the first to examine the impact of choice on child mental health outcomes.

The Parent Management Training-Oregon/PMTO Model

PMTO is a well-validated parent training prevention and treatment program to reduce child externalizing behavior problems (Forgatch & Patterson, 2010). The PMTO intervention is grounded in social interaction learning theory, teaching parents to monitor and modify coercive parent-child interactions via strategies to improve parenting (Forgatch, Patterson, & Gewirtz, 2013). PMTO includes five core components: skill encouragement, limit setting, monitoring, problem solving, and positive involvement. Randomized trials evaluating PMTO have demonstrated efficacy and effectiveness, showing benefits for children via reductions in externalizing problems, as well as other risk behaviors (for a comprehensive review see Forgatch & Gewirtz, 2017). Because the elementary years are a crucial age range for the onset of externalizing and related risk behaviors (e.g., substance use), PMTO provides an effective approach to prevent their development.

PMTO also provides a good laboratory for preference studies, because it is widely implemented and has an evidence-based implementation structure (see, e.g., Forgatch & DeGarmo, 2011; Forgatch & Gewirtz, 2017). Moreover, PMTO may be delivered in various modalities, including individual (home and clinic-based), and group formats. Individual sessions last for 50 minutes, and group sessions last for 90 minutes; both are provided on a weekly basis. Individual treatment may last for 3 to 9 months while group treatment includes 14 sessions with 6 to 10 parents per group. Each session consists of a warm-up activity, brief review of last week's homework, introduction of new topics, practice of new skills, and assignment of home practice. While positive outcomes are well established from intervention research on both individual and group formats of PMTO, no comparative effectiveness studies have yet examined differential dosage, participation, or outcomes across diverse formats of the intervention (e.g., group, individual, clinic, home), although one such study is underway (Gewirtz, 2014).

The current study: a doubly randomized preference trial of the Parent Management Training-Oregon/PMTO Model

In the current study we examined preferences for different formats of PMTO (i.e., group-based, home-based, clinic individual) and services as usual/SAU (i.e., child-focused interventions) among families presenting to children’s mental health clinics in a large Midwestern state. We hypothesized that random assignment to the choice condition would reduce child externalizing problems (i.e., parent and teacher report of conduct and hyperactivity-inattention problems) at six-months post-treatment completion, controlling for other factors known to influence child outcomes (i.e., parenting and parental mental health). Given the existence of an SAU condition, we also examined intervention selected or assigned (i.e., PMTO vs. SAU) as a moderator of child outcomes. We predicted that, within the choice condition, PMTO would outperform the SAU intervention; we were unsure how SAU vs. PMTO would perform in the no-choice condition.

Method

Procedures

Families with 5 to 12 year-old children with externalizing problems self-referring to one of three community mental health clinics in Detroit and its environs were informed of the opportunity to participate in a study during their intake process. Parents expressing interest provided permission for their contact information to be given to the study coordinator who called them to schedule the consent and baseline assessment process. Families were excluded from the study if the target child 1) had a pervasive developmental disability, 2) had previously received treatment for behavior problems, or if parents 3) had psychosis or lacked custody of the target child, or 4) were unwilling to be randomized. Participants were informed that this was a randomized controlled study to understand parents’ preferences for children’s mental health treatment, that participation was voluntary and their children’s treatment would not be affected if they chose not to participate. Assessments (of approximately one hour’s duration) were conducted in families’ homes, with one parent/caregiver and the target child. In-home assessments consisted of a series of parent-child interaction tasks described below. After checking for literacy and understanding of the measures, pencil-and-paper questionnaires were left in the home for the parent to complete, with a stamped, addressed envelope for the parent to return the questionnaires. Families received compensation for completing each assessment. All procedures were approved by the university IRB.

Following baseline assessment, families were randomized to choice or no-choice conditions. Within each condition, parents were again randomized, or offered choices between different formats of a parent training intervention, PMTO, and services-as-usual (SAU). Intervention formats included home-based PMTO, clinic-based individual PMTO, group-based PMTO, or services-as-usual. Families receiving PMTO modalities were treated by therapists certified in PMTO; families receiving SAU (a mix of cognitive behavioral and supportive psychotherapy) typically were treated by therapists with no PMTO training. All participating clinic therapists were licensed in psychology, social work or marriage and family therapy.

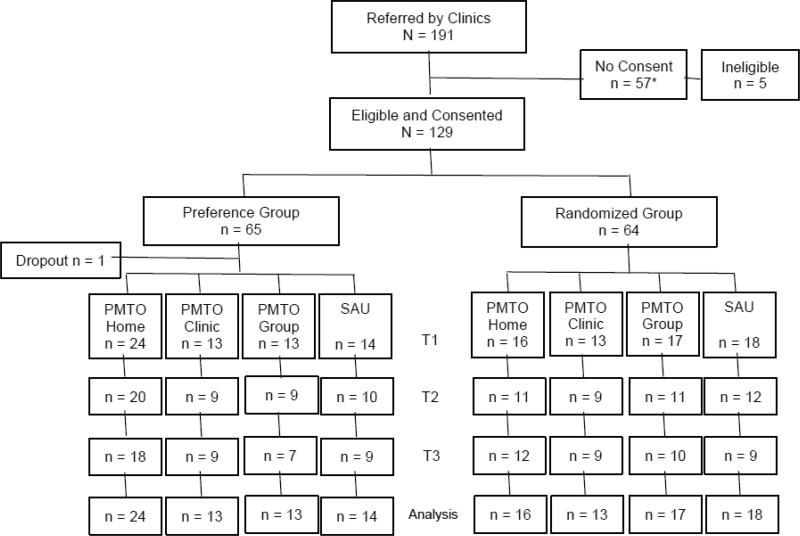

Families who chose or were randomized to SAU received services immediately; families who chose or were randomized to PMTO formats waited 3.2 months on average if PMTO was not available. Participants were assessed at baseline (T1), post-treatment (T2), and six months later (T3). Figure 1 presents a CONSORT diagram demonstrating the flow of families to conditions and the retention in each modality at each assessment. The current study utilized all data from all three time points.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of study participants

*N=57 no consents were as follows: n=23 were unresponsive to calls; n=15 reported being not interested/too busy to participate in research; n=10 had no information documented; n=3 had multiple broken consent/assessment appointments; n=3 were discharged/left clinic prior to consent; n=3 were found to be ineligible after referral.

Participants

Of the 191 families referred by the clinics to the study, 134 (70%) agreed to participate. Five families were later excluded from analyses, as it was revealed that their children had previously received services at the clinic, leaving 129 families in the final sample. Within each family, one parent was solicited as respondent/study participant together with the child referred to the clinic. Parent participants were typically mothers (126; 97.7%); just three (2.3%) were fathers. Household annual incomes reported by parents varied from zero to $130,000 per year with a median of $12,662; 75% reported annual household incomes below $20,000. Parents’ average age was 32.78 years (range of 21 to 63 years), and children’s average age was 7.69 years, with 65.1% boys and 34.9% girls. Most parents (60.2%) self-identified as African American; 30.1% as Caucasian; 5.3% multiracial, 2.7% Hispanic and 0.9% Native American. Only 13.5% of parents had completed a bachelor's degree. Information on living arrangements was received for 115 children (89%): 56 lived with single parents, 20 lived with two biological or adoptive parents, 24 lived with one parent and that parent’s partner, and 15 children lived with grandparents and other relatives. Ninety-two families remained in the study at T2 and 84 remained in the study at T3. Teacher rated child outcome data were difficult to collect in this sample of low-income, culturally diverse families. We collected teacher data for n=91 children at baseline, n=59 at T2, and n=52 at T3. Sixteen children (12.4%) had no teacher data over the course of the three assessment waves.

In an earlier study with this sample, we documented participant engagement (He et al., 2016). As is unfortunately typical with outpatient children’s mental health services (Gopalan et al., 2010), overall attrition from services was significant: almost two-thirds of the total sample either did not participate in the intervention at all (25.6%), or left prior to discharge (40.3%). Families randomized to the no-choice condition were three times more likely to drop out of treatment than families who were randomized to choose their preferred intervention modality (OR=3.12, 95%CI=1.18–8.29, p = .022), regardless of service modality (He et al., 2016). Within the choice condition, the most preferred modality was home-based PMTO (40.7% of the choice group selected this option); the remaining conditions (i.e., group-based, individual clinic-based, and services-as-usual/supportive child psychotherapy) were preferred equally.

Measures

Demographics

Parents reported their gender, age, education, ethnicity, marital status/living arrangements, annual household income and their child’s gender, ethnicity, and age.

Covariates

We examined parental mental health symptoms and parenting practices as covariates, as both have been shown to influence child externalizing symptoms. The Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18; Derogatis & Savitz, 2000) is an 18-item self-report questionnaire that assesses individuals’ psychological problems including anxiety, depression, and somatization (each is a separate scale) that occurred over the past week. Parents rated their psychological adjustment using BSI-18. The total score of the three 5-point subscales from 0 to 4 (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) were computed to represent a global severity index of overall psychological distress (α = .93) which was used in the data analysis. Higher scores on the BSI-18 suggest more severe problems.

Parents and children participated in seven videotaped Family Interaction Tasks (FITs). FITs included two 5-minute problem-solving tasks, three teaching tasks/games, a 5-minute monitoring task, and a 5-minute safety issues task. Trained coders blind to study conditions provided global ratings which yielded scores for positive (family problem-solving, positive involvement, skill encouragement, monitoring), and coercive parenting (inept discipline/non-contingent parenting). Coders scored FITs using a Coder Impressions system (Forgatch, Knutson, & Mayne, 1992). In prior observational studies of parent-child relationships in families with 5–12 year olds, FIT codes demonstrated ecological validity, construct validity, and sensitivity to change with at-risk families (e.g., Forgatch, Patterson, Degarmo, & Beldavs, 2009; Gewirtz, DeGarmo, Lee, Morrell, & August, 2015). Inter-rater reliability was assessed with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for randomly selected coder teams; 20% of videos were double coded for reliability. Global ratings loaded into parenting practices subscales of 4 items (monitoring) or 8–10 items (all other subscales). Sample items for problem solving evaluated the quality, extent, and satisfaction of the solution (α = .92, ICC = .88 – .92); harsh discipline assessed overly strict, authoritarian, or haphazard parenting (α = .80; ICC = .73 – .78); positive involvement evaluated parent’s warmth, empathy, etc. (α = .88; ICC = .76 – .78); skill encouragement reflected parent’s ability to promote children’s skill development through encouragement and scaffolding (α =.79; ICC = .73 – .77); monitoring assessed parents’ supervision and knowledge of their child’s daily activities (α = .74; ICC = .74 – .78). The final parenting scores were composites of the 5 indicators scaled 1 to 5.

Youth outcomes

The Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, Meltzer, & Bailey, 1998) is a 25-item questionnaire assessing child psychological adjustment in five domains: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity-inattention difficulties, peer relationships, and prosocial behavior. Teacher and parent versions were used in this study. Items are rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale (0 = not true, 1= somewhat true, 2 = certainly true). With five items per scale, the subscale scores range from 0 – 10. The measure has good reliability and validity (Goodman, 2001; He, Burstein, Schmitz, & Merikangas, 2013). Because the interventions targeted children’s externalizing problems, the current study outcomes were only the externalizing subscales (i.e., conduct problems (teacher alpha = .76, parent alpha = .71), and hyperactivity-inattention (teacher alpha = .88, parent alpha = .77 subscales).

Data Analysis

Group comparisons on demographic variables were conducted using t tests or ANOVAs for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Effects of preference on outcomes were analyzed using two-level mixed modeling, with time points nested within individual. Analyses were conducted using SAS Proc Mixed (Littell, Stroup, Milliken, Wolfinger, & Schabenberger, 2006).

An intent-to-treat approach was applied wherein all randomized participants were included in the analyses regardless of level of participation, missing data, or dropout status. Full information maximum likelihood method in SAS Proc Mixed was used to handle missing data (Graham, 2009). The mixed models included main effects of time and preference condition, and interaction effect of Time × Preference condition. To explore whether preference effect on child outcomes was moderated by the different intervention modalities, a two-level mixed model was applied including a three-way interaction of Time × Preference × Modality. Two-way interactions and main effects were also included in the model. All outcome analyses controlled for parent’s BSI global symptom index and parenting practices scores as time-varying covariates. Advantages of models using time-varying covariates, instead of only baseline covariates, include that they do not assume constant relationships between baseline covariates and repeatedly measured outcomes, and the models account for the longitudinal relationship between the repeatedly measured covariate and outcome (e.g., McCoach & Kaniskan, 2010). Parental psychopathology and parenting behavior were included as covariates because research shows that these factors are associated with child psychosocial functioning (Burke, Loeber, & Birmaher, 2002; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2004). We tested the intervention effects on child psychosocial functioning outcomes that were above and beyond the effects of the parental factors on the child outcomes. Site (i.e., clinic) was also controlled for in all analyses by including dummy variables in the models. An alpha level of < .05 was used to determine significance.

Results

Group Comparisons on Baseline Demographic and Characteristic Variables

Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviations for continuous variables, and percentages for categorical variables. There were no demographic or baseline characteristic differences between choice and no-choice groups. Attrition analyses comparing those who remained in the study (n=84) with those who dropped out (n=45) showed no significant differences in the demographic and characteristic variables between the groups. Comparisons between the three clinic sites revealed significant differences in parent education, income, parent BSI global severity index, parenting behavior, and parent-rated child conduct problems. One site had parents with, on average, significantly lower income level, higher BSI global severity index, lower positive parenting, and lower parent education status. Another site had significantly higher parent ratings on the SDQ conduct problems compared to the other sites. Differences among the four treatment modalities were tested within each condition at baseline. In the choice condition, parents choosing SAU had significantly lower positive parenting scores compared to the other modalities. In the no-choice condition there were no significant differences in baseline demographic or characteristic variables between the four modalities.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the choice and No-choice groups

| Variables | Choice (n=65) | No-choice (n=64) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Gender (male %) | 69.2 | 60.9 | .323 | |

| Child age (M, SD) | 7.71 (2.19) | 7.67 (1.78) | .919 | |

| Parent age (M, SD) | 32.28 (8.92) | 33.25 (7.03) | .520 | |

| Annual Income (M, SD) | 18,240 (16,190) | 19,771 (23,854) | .695 | |

| Parent race (%) | .633 | |||

| African-American | 60.3 | 60.0 | ||

| Caucasian | 27.6 | 32.7 | ||

| Other | 12.1 | 7.3 | ||

| Parent Education (%) | .747 | |||

| Less than HS | 15.5 | 18.2 | ||

| HS graduate | 17.2 | 23.6 | ||

| Some college | 51.7 | 47.3 | ||

| College graduate | 13.8 | 10.9 | ||

| Post-college degree | 0.0 | 1.7 | ||

| Treatment Modality (%) | .452 | |||

| Group-based PMTO | 20.3 | 26.6 | ||

| Clinic-based PMTO | 20.3 | 20.3 | ||

| Home-based PMTO | 37.5 | 25.0 | ||

| Child therapy (SAU) | 21.9 | 28.1 | ||

| Parent BSI (M, SD) | 15.11 (12.52) | 18.93 (16.40) | .151 | |

| Parenting score (M, SD) | 2.16 (0.34) | 2.13 (0.40) | .643 | |

| SDQ Teacher (M, SD) | ||||

| Conduct Problems | 3.79 (2.53) | 3.81 (2.94) | .969 | |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | 7.63 (2.91) | 6.47 (3.21) | .074 | |

| SDQ Parent (M, SD) | ||||

| Conduct Problems | 5.44 (2.45) | 4.97 (2.61) | .310 | |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | 8.34 (2.04) | 7.85 (2.36) | .223 | |

Effects of Choice vs. No-choice on Teacher-Rated Child Outcomes

Raw means and standard deviations of the teacher-rated SDQ subscale scores are presented in Table 2. Mixed model analyses showed a significant effect of Time × Choice condition on the teacher-rated hyperactivity/inattention scale scores [F(1, 99.5) = 5.38, p = .022, d = 0.28]. Inspection of the predicted means showed a steady decline in hyperactivity/inattention scores for the choice group over time, while the no-choice group had a slight increase in the scale scores over time (Figure 2). There was a significant time effect for conduct problems [F(1, 61.7)=4.12, p = .047], in which both groups showed improvements over time. In summary, all students showed declines in conduct problems, however only students in the preference group also showed declines in hyperactivity/inattention.

Table 2.

Raw means and standard deviation of teacher-rated and parent-rated SDQ scores for the choice and No-choice groups

| choice | No-choice | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| SDQ Teacher | ||||||||||||

| Conduct problems | 3.79 | 2.53 | 3.64 | 3.20 | 3.77 | 2.76 | 3.81 | 2.94 | 4.04 | 3.09 | 2.69 | 2.69 |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | 7.63 | 2.91 | 6.18 | 3.21 | 6.69 | 2.87 | 6.47 | 3.21 | 6.42 | 3.56 | 6.69 | 3.21 |

| SDQ Parent | ||||||||||||

| Conduct problems | 5.44 | 2.45 | 4.50 | 2.58 | 4.71 | 2.35 | 4.97 | 2.61 | 4.10 | 2.57 | 3.49 | 2.23 |

| Hyperactivity/Inattention | 8.34 | 2.04 | 7.55 | 2.17 | 7.27 | 2.28 | 7.85 | 2.36 | 6.88 | 2.41 | 6.59 | 2.23 |

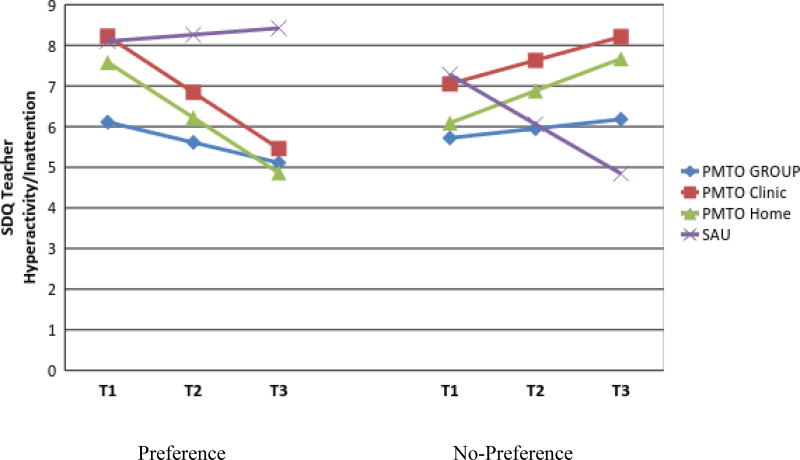

Figure 2.

Effect of Preference × Time on the teacher-rated SDQ Hyperactivity/Inattention scale. Estimated marginal means adjusted for covariates are presented. Model included site, parent BSI 18 global severity, and parenting scores as time-varying covariates. SDQ = Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman et al., 1998); BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (Derogatis, 2001).

Effects of Choice vs. No-choice on Parent-Rated Child Outcomes

Table 2 presents the raw means and standard deviations of the parent-rated SDQ subscale scores. Mixed model analyses showed no significant Time × Choice condition effect on either of the SDQ subscale scores. Significant time effects were detected on hyperactivity/inattention [F(1, 94.4) = 14.91, p < .001], and conduct problems [F(1, 90.7) = 17.77, p < .001]. In summary, all students showed declines in parent-rated conduct problems and hyperactivity/inattention with no significant difference between Choice and No-Choice conditions in rates of change over time.

Moderation effect of Intervention Modality on Child Outcomes

Mixed model analyses testing the moderation effect of intervention modality on the relationship between Preference conditions and child outcomes showed that there was a significant Time × Choice × Modality effect on the teacher-rated SDQ hyperactivity/inattention [F(3, 91.5)=4.16, p = .008]. Children of parents who chose to receive PMTO interventions showed improvements in hyperactivity/inattention compared to those who chose SAU and to those who were randomized to PMTO interventions (Figure 3). Interestingly, children of parents who were randomized to SAU also showed improvements in hyperactivity/inattention over time.

Figure 3.

Depiction of the three-way interaction of Time X Preference X Modality on the SDQ-teacher Hyperactivity/Inattention scores. Estimated marginal means adjusted for covariates are presented. Model included site, parent BSI global severity, and parenting scores as time-varying covariates. SDQ = Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman et al., 1998); BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (Derogatis, 2001). Preference No-Preference

Discussion

In this study we sought to understand whether offering parents their choice of intervention would benefit child externalizing symptoms among families seeking mental health services. Findings provided partial support for the hypothesis that provision of choice to parents would be associated with better child outcomes, with teacher, but not parent report indicating that from baseline to six months following the end of intervention, hyperactivity/inattention problems decreased significantly more for children in the choice vs. no-choice conditions. We speculate that the lack of differences in parent ratings across choice/no-choice groups may be because all parents, having sought and received services for their children’s externalizing problems, expected that their children’s behavior would improve. There may also be a regression to the mean, in that the start of the study (baseline assessment) was immediately pre-treatment and presumably, when child problems were most salient to parents.

Within the choice condition, teachers rated the children whose parents had selected PMTO with fewer inattention/hyperactivity problems compared with children whose parents selected SAU, and compared with children assigned to PMTO in the no-choice condition. Providing choice may motivate parents by increasing their investment in the intervention of choice. Indeed, earlier, we documented that provision of choice reduced drop-out in this study (He et al., 2016). Parents able to select their preferred intervention appear, then, to have more exposure to PMTO tools, and may be more motivated to use them to shape their children’s behaviors. The PMTO focus on scaffolding children by breaking down tasks into small steps and rewarding on-task behavior benefits children dealing with inattention and impulsive, hyperactive behaviors (Patterson, DeGarmo, & Knutson, 2000). With parents providing more structure at home, children may be more responsive to the high levels of structure at school. Teachers are astute observers of children’s behavior and teacher reports are considered less biased than parent reports of externalizing behavior (Stanger & Lewis, 1993). We speculate that teachers may be better able to discern differences in off-task behavior than parents because the school day requires more structure and therefore small changes in behavior may be more obvious to teachers than to parents. At least one prior parent training program evaluation examining children at risk for externalizing behaviors also has documented teachers reporting improvements that parents do not report (Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2001).

Across both choice and no-choice conditions, parents and teachers reported improvements in child conduct problems, with no differential improvement in the choice condition. It is possible that differential change (i.e. choice/no-choice) was noted with hyperactive/inattention problems but not with conduct problems, as the latter (assessed by items asking about fighting, lying/cheating, stealing) are more serious behavior problems that may take longer to remit than hyperactivity problems (assessing restless, fidgeting, impulsivity). It remains to be seen whether differential improvements in choice vs. no-choice groups would emerge on conduct problems over a longer follow-up period. In future we plan to follow larger samples over time to ascertain change beyond the 6-month post-intervention period of this study.

In addition to the main effect of choice on teacher-reported hyperactivity/inattention, the moderation analyses demonstrated significant improvements in families who selected PMTO, compared with SAU, and compared with families in the no-choice condition. Interestingly, families in the choice condition with lower parenting skills were more likely to select SAU than PMTO (which ultimately resulted in less benefit to children). This highlights the importance not only of being offered a choice of intervention, but also of making an informed choice (i.e. selecting an intervention documented to improve externalizing behaviors). These findings also point to the need to further elucidate how parents make choices about interventions for children’s conduct problems. We were not able to gather detailed data on the extent of information given to parents about the availability of the different treatment options (i.e. wait time for PMTO), or to what extent clinics provided information to parents about the content and evidence behind the interventions. We speculate that little information was provided to parents beyond the basics (e.g. that parent participation was not needed for child therapy, but was required for PMTO).

Decision aids, increasingly used in medical decision-making (Winston, Grendarova, & Rabi, 2017) likely would help parents make informed choices for child externalizing problems. For example, decision aids might help parents to weigh up the expected benefits of a parenting vs. child intervention given what is known about individual/family differences that might enhance or reduce treatment effectiveness. These could be used in conjunction with motivational interviewing-type interventions, to encourage parents to engage, and complete interventions – like PMTO - that require more parental investment in attendance and practice. Family Check-Up (e.g. Dishion et al., 2008) is the first adaptive parenting intervention that incorporates a motivational interviewing assessment with a tailored approach to subsequent parent training components. With extensive data for its effectiveness, Family Check-Up provides a model for the extension of PMTO as an adaptive intervention.

While PMTO showed strong evidence in reducing child externalizing symptoms in the choice condition, it was perplexing to find that when choice was not offered (i.e., when parents were simply assigned to intervention), SAU outperformed the parenting interventions on teacher ratings of child inattention/hyperactivity problems. Indeed, SAU in the no-choice condition appeared to be as effective as the PMTO interventions in the choice condition (Figure 3). We proffer two possible explanations for this. First, drop out among the PMTO modalities was particularly high in the no-choice, compared to the choice condition; participants randomized to SAU completed seven sessions, on average, compared with zero (group) to four (home-based) sessions in the no-choice PMTO conditions. Parent participation in PMTO requires far more effort from parents than SAU/child-focused therapy: role play and practice of parenting skills in-session, plus ongoing home practice assignments. Parents’ assignment to (rather than choice of) PMTO likely had a detrimental impact on their participation and child outcomes. Second, children in families assigned to (or selecting) SAU could start intervention immediately, compared with a three-month wait for PMTO. We speculate, then, that children assigned to SAU may have received a ‘solid dose’ of CBT from a therapist; sufficient, possibly, to provide those children with individual skills to improve off-task school behaviors, and thus teacher reports of inattention/hyperactivity. Our findings stand in contrast with the body of literature showing the superiority of parent training to address children’s externalizing problems over the longer-term. However, in the short term, it may be that child-focused therapy can benefit children in households where parents cannot, or are not interested in accessing parenting interventions. Clearly, research with a larger sample over a longer time period is needed to further understand these findings.

This was a relatively small study, powered only to detect the strongest differences between groups. The sample was predominantly low-income, diverse, single parents, and thus results may not generalize to other populations. A key drawback was the large dropout from services, which, while not atypical for community mental health services, was challenging for the study. Conducting preference trials in community settings is important for external validity, but these endeavors also must wrestle with the harsh reality of what this study was intended to inform: the high dropout rates, and low reach of children’s mental health interventions.

Overall, the study findings suggest that paying attention to participant preferences in intervention provides some benefits to families. Outpatient clinics provide treatment, but also deliver targeted prevention programs for youth identified as at-risk for (but not diagnosed with) externalizing disorders, similar to the youth in this study. Neither treatment nor prevention programs typically address parents’ preferences, with the exception of Family Check Up (Dishion et al., 2008). The predominantly low-income families in this study are important targets for prevention. Many empirically-supported prevention programs address child externalizing behaviors but few studies examine parental preferences; this study is a first step in that direction.

Acknowledgments

Funding. The research reported here was funded by grant no. P20 MH 079906 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Gerald August (Center PI) and Abigail Gewirtz (PI of this study)

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical approval. This study was approved by the University of Minnesota IRB and the Human Subjects Research Protection Board of the State of Michigan’s Department of Community Health. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Disclosure potential conflicts of interest. The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arnkoff DB, Glass CR, Shapiro SJ. Expectations and Preferences. In: Norcross JC, editor. Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 335–356. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Nix RL, Maples JJ, Murphy SA, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Examining clinical judgment in an adaptive intervention design: The fast track program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:468–481. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Bradley C. Patient preferences and randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 1989;299:313–315. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6694.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Horwitz SM, Schwab-Stone ME, Leventhal JM, Leaf PJ. Mental health in pediatric settings: disorders and factors related to service use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:841–849. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL. Race differences in the receipt of mental health services among young adults. Psychological Services. 2012;9:38–48. doi: 10.1037/a0027089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Loeber R, Birmaher B. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part II. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1275–1293. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke LE, Warziski M, Styn MA, Music E, Hudson AG, Sereika SM. A randomized clinical trial of a standard versus vegetarian diet for weight loss: the impact of treatment preference. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32:166–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, Gretton V, Miller P, Palmer B, Counselling versus Antidepressants in Primary Care Study Group Antidepressant drugs and generic counselling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomised trial with patient preference arms. BMJ. 2001;322:772–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark NM, Janz NK, Dodge JA, Mosca L, Lin X, Long Q, Liang J. The effect of patient choice of intervention on health outcomes. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2008;29:679–686. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:793–795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Chen Y, Deal K, Rimas H, McGrath P, Reid G, Corkum P. The interim service preferences of parents waiting for children’s mental health treatment: a discrete choice conjoint experiment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:865–877. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9728-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Deal K, Rimas H, Buchanan DH, Gold M, Sdao-Jarvie K, Boyle M. Modeling the information preferences of parents of children with mental health problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1123–1138. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard S, Mortensen PB, Frydenberg M, Thomsen PH. Long-term criminal outcome of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2013;23:86–98. doi: 10.1002/cbm.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Savitz KL. The SCL–90–R and Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in primary care. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The family check-up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobscha SK, Corson K, Gerrity MS. Depression treatment preferences of VA primary care patients. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:482–488. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.6.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Parenting through change: an effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:711–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Sustaining fidelity following the nationwide PMTOTM implementation in Norway. Prevention Science. 2011;12:235–246. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Gewirtz AH. Evolution of Parent Management Training-Oregon Model. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, editors. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. 3. New York: Guildford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Knutson N, Mayne T. Coder impressions of ODS lab tasks. Eugene, OR: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, Degarmo DS, Beldavs ZG. Testing the Oregon delinquency model with 9-year follow-up of the Oregon Divorce Study. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:637–660. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, Gewirtz AH. Looking Forward: The Promise of Widespread Implementation of Parent Training Programs. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8:682–694. doi: 10.1177/1745691613503478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, DeGarmo DS, Lee S, Morrell N, August G. Two-year outcomes of the Early Risers prevention trial with formerly homeless families residing in supportive housing. Journal of Family Psychology. 2015;29:242–252. doi: 10.1037/fam0000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH. Grant # W81XWH141014. Department of Defense; 2014–2019. Comparing web, group, and telehealth formats of a military parenting program. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Meltzer H, Bailey V. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;7:125–130. doi: 10.1007/s007870050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Goldstein L, Klingenstein K, Sicher C, Blake C, McKay MM. Engaging families into child mental health treatment: Updates and special considerations. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19:182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty KP, Skinner ML, MacKenzie EP, Catalano RF. A randomized trial of Parents Who Care. Prevention Science. 2007;8:249–260. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs N, Bertram H, Kuschel A, Hahlweg K. Parent recruitment and retention in a universal prevention program for child behavior and emotional problems: barriers to research and program participation. Prevention Science. 2005;6:275–286. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Burstein M, Schmitz A, Merikangas KR. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): the factor structure and scale validation in U.S. adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:583–595. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Gewirtz A, Lee S, Morrell N, August G. A randomized preference trial to inform personalization of a parent training program implemented in community mental health clinics. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2016;6:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0366-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis JH, Leon AC, Markowitz JC, Manber R, Arnow B, Klein DN, Thase ME. Patient preference as a moderator of outcome for chronic forms of major depressive disorder treated with nefazodone, cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, or their combination. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70:354–361. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan BM, Dimidjian S, Rizvi SL. Treatment preference, engagement, and clinical improvement in pharmacotherapy versus psychotherapy for depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:799–804. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Stroup WW, Milliken GA, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS for Mixed Models. Second. SAS Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Long Q, Little RJ, Lin X. Causal Inference in Hybrid Intervention Trials Involving Treatment Choice. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2008;103:474–484. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus SM, Stuart EA, Wang P, Shadish WR, Steiner PM. Estimating the causal effect of randomization versus treatment preference in a doubly randomized preference trial. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:244–254. doi: 10.1037/a0028031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG. Major depression and conduct disorder in youth: associations with parental psychopathology and parent–child conflict. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2004;45:377–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffery KJ, Turner R, Macaskill P, Walter SD, Chan SF, Irwig L. Determining the impact of informed choice: separating treatment effects from the effects of choice and selection in randomized trials. Medical Decision Making. 2011;31:229–236. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10379919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoach DB, Kaniskan B. Using time-varying covariates in multilevel growth models. Frontiers in Psychology. 2010;1:17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J-P, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and Treatment of Mental Disorders Among US Children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125:75–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian ND, Eisenhower AS, Carter AS. Targeted prevention of childhood anxiety. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2015;55:58–69. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9696-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng MY, Weisz JR. Annual Research Review: Building a science of personalized intervention for youth mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2016;57:216–236. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44:329–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS, Knutson N. Hyperactive and antisocial behaviors: comorbid or two points in the same process? Development & Psychopathology. 2000;12:91–106. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400001061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Ingram A, Wolchik S, Tein J-Y, Winslow E. Long-term effects of parenting-focused preventive interventions to promote resilience of children and adolescents. Child Development Perspectives. 2015;9:164–171. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz NK, Fabiano GA, Cunningham CE, dosReis S, Waschbusch DA, Jerome S, Morris KL. Systematic Review of Patients’ and Parents' Preferences for ADHD Treatment Options and Processes of Care. The Patient. 2015;8:483–497. doi: 10.1007/s40271-015-0112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Redmond C. Research on Family Engagement in Preventive Interventions: Toward Improved Use of Scientific Findings in Primary Prevention Practice. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;21:267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Lewis M. Agreement Among Parents, Teachers, and Children on Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;22:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Street RL, Jr, Elwyn G, Epstein RM. Patient preferences and healthcare outcomes: an ecological perspective. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 2012;12:167–180. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift JK, Callahan JL, Vollmer BM. Preferences. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67:155–165. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson DJ, Sibbald B. Understanding controlled trials. What is a patient preference trial? BMJ. 1998;316:360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner EA, Jensen-Doss A, Heffer RW. Ethnicity as a moderator of how parents’ attitudes and perceived stigma influence intentions to seek child mental health services. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2015;21:613–618. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston K, Grendarova P, Rabi D. Video-Based Patient Decision Aids: A Scoping Review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymbs FA, Chen Y, Rimas HM, Deal K. Examining parents’ preferences for group parent training for ADHD when individual parent training is unavailable. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2017;26:888–904. [Google Scholar]

- Wymbs FA, Cunningham CE, Chen Y, Rimas HM, Deal K, Waschbusch DA, Pelham WE., Jr Examining Parents’ Preferences for Group and Individual Parent Training for Children with ADHD Symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2015:1–18. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1004678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy WS, Jr, McVay MA, Voils CI. Effect of allowing choice of diet on weight loss--in response. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;163:805–806. doi: 10.7326/L15-5159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]