Abstract

Aim

Previous research indicates that preventive intervention is likely to benefit patients “at risk” of psychosis, in terms of functional improvement, symptom reduction and delay or prevention of onset of threshold psychotic disorder. The primary aim of the current study is to test outcomes of ultra high risk (UHR) patients, primarily functional outcome, in response to a sequential intervention strategy consisting of support and problem solving (SPS), cognitive-behavioural case management and antidepressant medication. A secondary aim is to test biological and psychological variables that moderate and mediate response to this sequential treatment strategy.

Methods

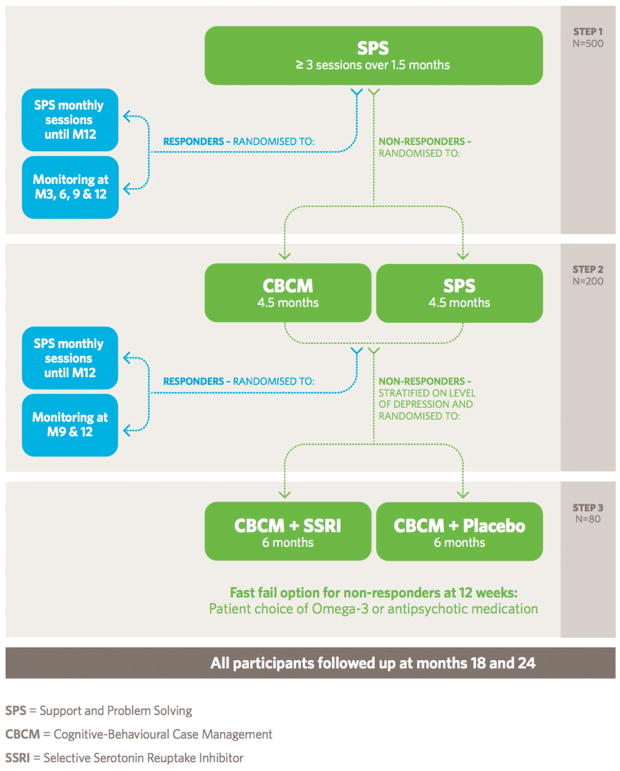

This is a sequential multiple assignment randomised trial (SMART) consisting of three steps: Step 1: SPS (1.5 months); Step 2: SPS vs Cognitive Behavioural Case Management (4.5 months); Step 3: Cognitive Behavioural Case Management + Antidepressant Medication vs Cognitive Behavioural Case Management + Placebo (6 months). The intervention is of 12 months duration in total and participants will be followed up at 18 months and 24 months post baseline.

Conclusion

This paper reports on the rationale and protocol of the Staged Treatment in Early Psychosis (STEP) study. With a large sample of 500 UHR participants this study will investigate the most effective type and sequence of treatments for improving functioning and reducing the risk of developing psychotic disorder in this clinical population.

Keywords: antidepressant medication, clinical trial, prodrome, psychosis, ultra high risk

1 | INTRODUCTION

Since our first intervention trial in the “ultra high risk” (UHR) for psychosis population in the late 1990s (McGorry et al., 2002), 11 further randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted, testing a range of psychological, pharmacological, nutritional and multicomponent psychosocial interventions. A recent meta-analysis (van der Gaag et al., 2013) found that the risk reduction of experimental interventions compared to control interventions was 54% over 12 months with a Number Needed to Treat (NNT) of 9. Cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) has been found to be of particular benefit and safety, with another meta-analysis indicating that it reduces the relative risk of developing psychosis by 50% at 6, 12 and 18–24 months (Hutton & Taylor, 2013). Integrated psychosocial interventions have also been shown to be of benefit (Bechdolf et al., 2012; Nordentoft et al., 2006). Antipsychotic medication has also shown some efficacy, although a less favourable risk-benefit ratio means that it is not appropriate for first line therapy (McGlashan et al., 2006). Omega-3 fatty acids have shown a strong and sustained benefit in one double-blind placebo-controlled trial (4.9% vs 27.5% at 12 months, P < .007) (Amminger et al., 2010), but we failed to replicate this finding in a subsequent larger-scale study(McGorry et al., 2017).

Naturalistic data has been reported suggesting that antidepressant medication may be effective in reducing the risk of transition in UHR patients (Cornblatt, Lencz, et al., 2007; Fusar-Poli, Valmaggia, & McGuire, 2007; Fusar-Poli et al., 2015). For example, Fusar-Poli et al. (2015) reported naturalistic data that antidepressant medication in conjunction with cognitive behaviour therapy was associated with greater benefits than antipsychotic medication in conjunction with cognitive behaviour therapy. The high rate of prescription of antidepressant medications (61% of the cohort) in our recent omega-3 intervention trial may have contributed to the low transition rate observed in that study (McGorry et al., 2017). However, another study failed to find support for antidepressant medications improving symptom progression in UHR patients (Walker et al., 2009). To date, the effect of antidepressant medications in this population has not been tested in a controlled trial. Antidepressants could reduce risk by improving mood and thereby indirectly reducing faulty appraisal of anomalous experiences linked to future psychosis. They may also modulate response to environmental stress and adversity, which has been found to increase risk for psychosis (Cantor-Graae, 2007; Fusar-Poli et al., 2007). This effect may occur either directly via acting on the neurochemical pathways that mediate stress response (Berton et al., 2006) or indirectly by preventing depression, affective dysregulation and anxiety secondary to these stressors (Garner et al., 2005; van Rossum, Dominguez, Lieb, Wittchen, & van Os, 2011; Yung, Buckby, et al., 2007). Consistent with this, Cornblatt et al. (2003) proposed that antidepressants may reduce some of the underlying core vulnerability factors (mood disturbance, social isolation, school failure) and thereby relieve the stress that might otherwise exacerbate attenuated psychotic symptoms. It also appears that antidepressants may possess some neuroprotective properties (Chen et al., 1999; Michael-Titus, Bains, Jeetle, & Whelpton, 2000; Sanchez et al., 2001), which may halt a neurodegenerative process associated with the evolution of psychotic disorder.

Longer term follow up of the relatively brief interventions trialled to date reveals significant differences in transition rate tend to be lost over time (McGlashan et al., 2006; Morrison et al., 2007; Phillips et al., 2007). In the first intervention trial in this group, the benefits that were associated with a combined antipsychotic medication/CBT intervention over the 6 month treatment period were not maintained at 12 month (McGorry et al., 2002) and medium term follow up (Phillips et al., 2007). Similarly, trend benefits in favour of olanzapine compared to placebo during the treatment year were not maintained over the follow-up year (McGlashan et al., 2006), nor were lower transition rates associated with CBT over a 6 month treatment period maintained at medium term follow up (Morrison et al., 2007). However, in contrast, Ising and colleagues (Ising et al., 2016) reported a benefit of CBT over treatment as usual at the 4-year follow-up point. Overall, this suggests that the intervention for most patients may have merely delayed onset through reducing risk during the period of treatment. It also suggests different treatments, sequences and durations of therapy may be needed for sustained benefits, as seen with early psychosis services in general (Bertelsen et al., 2008; Craig et al., 2004; Garety et al., 2006; Nordentoft et al., 2004; Norman, Windell, Manchanda, Harricharan, & Northcott, 2012). The first generation of UHR trials have generally been modest single site studies testing one or two candidate therapies in single step, head-to-head designs. The next step is for further trials to determine the most effective type, sequence and duration of interventions, and how they might best be personalized or tailored to individual patients, based on clinical presentation, response profile and perhaps ultimately through the use of biomarkers or psychosocial variables.

1.1 | Broadening the outcomes of interest: Functioning and non-psychotic outcomes

The UHR criteria have shown good predictive validity for progression of the psychosis phenotype, consistent with their original purpose. However, this special valence for psychosis outcomes has been shown to coexist with an increased risk of persistent subthreshold psychotic symptoms (41%), other non-psychotic syndromal outcomes (up to 40%) and a cross-diagnostic risk of poor functional outcome in a substantial minority (Addington et al., 2011; Fusar-Poli & Van Os, 2013; Simon et al., 2013; Yung, Nelson, et al., 2011). Even if UHR patients do not transit to psychosis, persistent subthreshold positive symptoms and/or mood and anxiety symptoms may seriously disable, and these syndromes are often not treated due to poor access to or engagement in subsequent care. Adopting a broader perspective for UHR treatment is congruent with the general move to prioritize social and occupational recovery as a primary target for intervention in all mental disorders (Alvarez-Jimenez et al., 2012).

1.2 | Declining transition rates and need for larger-scale, sequentially enriched studies

Another recent observation has been the declining transition rate in UHR cohorts worldwide. Early studies reported 12-month transition rates in the 30–40% range whereas more recent studies have reported rates of 10–20% (Fusar-Poli et al., 2012; Yung, Yuen, et al., 2007). The precise reasons for this are unclear, but may include a combination of lead-time bias (Nelson et al., 2013), earlier intervention (Nelson et al., 2016), a change in clinical characteristics of cohorts (Hartmann et al., 2016), referral pathways (Wiltink, Velthorst, Nelson, McGorry, & Yung, 2015) and treatment changes. The fact that UHR patients are not only already symptomatic but also functionally impaired underlines the need to clarify an evidence-based intervention sequence which may be translated directly into clinical practice. However, the declining transition rate does reduce power and highlight the need for larger sample sizes and sequential strategies to enrich risk.

1.3 | The clinical staging model

The clinical staging model is a transdiagnostic heuristic approach aimed at understanding the neurobiological and psychosocial processes underpinning the onset and course of mental disorders. Clinical staging, through integrating stage and timing with evolution of clinical phenotype, also allows interventions to be tested from a preventive standpoint in reducing the risk of progression and persistence of illness, with less risk and greater potential benefit (McGorry, 2007a, 2013; McGorry, Hickie, Yung, Pantelis, & Jackson, 2006; McGorry & van Os, 2013). Staging is a pragmatic blend of categorical and dimensional approaches which aims for clinical and research utility, providing a heuristic framework to study the significance of biomarkers by stage and clinical phenotype, psychosocial risk factors and treatment response.

Applying the clinical staging model to UHR intervention means that a staged approach to treatment is offered, with the safest, most benign and least specialized interventions used initially, and “stronger,” more intensive interventions, with potentially more adverse effects, reserved for those who do not respond to the earlier stages of intervention. This adaptive strategy also addresses the lower transition rate through a stepwise enrichment of the sample such that non-responders to initial simpler interventions will be enriched for both higher transition rates to psychosis and for greater functional impairment. The staging model also hypothesizes that timing of intervention is critical in that therapeutic agents/strategies with neuroprotective and psychoprotective qualities will be most beneficial in this subthreshold stage of disorder in reducing the impact of the disease process. Finally, this staged approach to UHR intervention addresses ethical concerns regarding intervention in this group, namely the “false positive” issue, potential stigma, and a perceived relative lack of predictive power (Warner, 2001). Since there is a need for care for the presenting clinical problems, then providing safer, nonspecific and benign interventions as a first step will allow those with milder and responsive or self-limiting problems to remit, while those who fail to benefit can progress to more intensive or relatively more specific interventions. This ensures an “enriched” sample, with fewer false positives for both persistent and more severe illness (of any phenotype) and also for transition to psychosis, in which to test more specific intervention strategies.

1.4 | Neuroprotection, inflammation and oxidative stress

Current biological treatment options for established psychoses have predominantly centred on the dopamine theory. However, it is unclear how central this theory is likely to be for UHR patients (Howes & Kapur, 2009; Kaur & Cadenhead, 2010). In addition, the side effects of dopamine antagonists (ie, antipsychotic medications) significantly limit their preventive use. There is now a clear body of evidence to support a role for both inflammation and oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders (Fineberg & Ellman, 2013; Flatow, Buckley, & Miller, 2013). There is a consistent evidence of increased blood concentrations of inflammatory cytokines (Miller, Buckley, Seabolt, Mellor, & Kirkpatrick, 2011). Inflammatory abnormalities are present in patients with first-episode, drug-naïve psychosis (FEP) compared with controls, suggesting an association independent of antipsychotic medication. Furthermore, the concentrations of some inflammatory molecules vary with the clinical status of patients, that is, there appear to be separate groups of state and trait markers. State-related markers include interleukin (IL) 1-beta, IL-6 and transforming growth factor-beta. IL-12, interferon-gamma and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) appear to be trait markers (Kirkpatrick & Miller, 2013). Oxidative stress, a state where the levels of available antioxidants is reduced, or the levels of oxidative species is increased, is well documented in schizophrenia and related psychoses (Flatow et al., 2013), with abnormal oxidative stress parameters reported in peripheral blood cells (ie, erythrocytes, neutrophils, platelets), cerebrospinal fluid and postmortem brain. Inflammation and oxidative stress also reciprocally induce each other in a positive feedback manner (Bitanihirwe & Woo, 2011). The incorporation of these factors into traditional monoamine neurotransmitter-system models facilitates a more comprehensive model of disease, potentially underpinning course of illness in psychotic disorders (Berk et al., 2011). This in turn has facilitated the identification of new therapeutic targets and neuroprotective treatments that have the potential to interrupt the identified neurotoxic cascades (Dodd et al., 2013). Although the current study will not test a pharmacological agent that targets these potential pathogenic mechanisms, relevant biological markers will be measured to assess their predictive value and whether they moderate outcome.

1.5 | Psychoprotection

The cognitive model of psychosis posits that dysfunctional interpretations of anomalous experiences contribute, against a background of pre-existing biopsychosocial vulnerability, to the emergence and maintenance of psychotic symptoms (Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Free-man, & Bebbington, 2001; Morrison, 2001). These consist of cognitive biases (Garety & Freeman, 1999) that emerge from underlying “core” beliefs or schemas about the self and world that have become entrenched during an individual’s developmental years. During the prodromal stage of psychosis, it is thought that such biases contribute to the evolution of attenuated into frank psychotic symptoms (French, 2002; Phillips & Francey, 2004). CBT for UHR individuals aims to identify, manage and correct these cognitive biases and dysfunctional interpretations of anomalous experiences through a variety of talking therapy and behavioural techniques and thereby diminish the risk of developing full-threshold psychotic disorder (Morrison, 2002; Phillips & Francey, 2004). In this way, CBT may function as a form of “psychoprotection”(Susser & Ritsner, 2010) against cognitive vulnerabilities. In several trials to date, CBT has proven effective in UHR samples (NNT = 13), although a link to the underlying mechanism of reducing cognitive biases and preventing the formation of delusional explanations of anomalous experiences, a focus of the present design, has not yet been clearly demonstrated.

Although CBT has been found to be more effective than monitoring it is not yet clear whether it is more effective than other, less intensive psychotherapies. In a trial comparing risperidone, CBT and supportive therapy, supportive therapy resulted in the same degree of symptomatic and functional improvement in UHR patients as CBT (McGorry, Nelson, et al., 2013; Yung, Phillips, et al., 2011). The current study will test cognitive-behavioural case management (CBCM), an intervention that delivers CBT in a case management format. It will therefore allow for further investigation of whether CBT provides additional advantages over supportive therapy for this patient group.

1.6 | Neurocognitive and neurobiological predictors of psychosis

There is considerable literature showing that reduced neurocognitive performance predates the onset of frank psychotic symptoms and is evident in childhood (Cannon et al., 2002) and adolescence (Davidson et al., 1999) in people who go on to develop schizophrenia. UHR patients also show reduced neurocognitive performance compared to healthy controls across a range of domains (Brewer et al., 2006). Within this group, those who transition to psychosis show even greater decrements. The precise pattern of neurocognitive deficits in those who transition is yet to be determined. However, the most consistent findings relate to reduced memory and executive function performance (Becker et al., 2010; Brewer et al., 2005; Eastvold, Heaton, & Cadenhead, 2007; Kim et al., 2011; Lencz et al., 2006; Mesholam-Gately, Giuliano, Goff, Faraone, & Seidman, 2009; Niendam et al., 2014; Pukrop et al., 2007; Riecher-Rössler et al., 2009; Seidman et al., 2010; Woodberry et al., 2010). Neurocognition will be assessed in the current study in order to probe the cognitive deficits that mark the pre-onset phase of psychotic disorder and whether neurocognitive profiles predict outcome and moderate/mediate response to treatment.

A key question in the aetiology of psychotic disorders is whether the brain changes seen in post-mortem and imaging studies of patients with long-standing illness arise during the development of the illness and, if so, whether they represent a potential target for intervention. Significant reductions in grey matter in various brain regions have been observed across the transition to psychosis in UHR samples (Borgwardt et al., 2008; Job, Whalley, Johnstone, & Lawrie, 2005; Pantelis et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2009; Takahashi, Wood, Yung, Soulsby, et al., 2009; Takahashi, Wood, Yung, Phillips, et al., 2009). White matter also shows changes around the time of transition to psychosis (Walterfang et al., 2008). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans will be performed in the current study in order to further assess these changes and whether neuroimaging parameters predict outcome and moderate/mediate response to treatment.

1.7 | Gene-environment interaction

An important current in psychosis research is understanding how genetic and environmental factors interact to contribute to the onset and evolution of psychotic disorders (EU-GEI, 2008; Sham, 1998). The current study will collect biological samples of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Sekar et al., 2016) for genetic analysis in order to investigate whether gene by environment interactions predict outcome and moderate/mediate response to treatment.

1.8 | Internationally unique enhanced primary care platforms

The Australian headspace system is a nationwide platform of care for young people, which has already enabled access to clinical and social care to over 100 000 young Australians aged 12–25 years with emerging mental ill health. The system is essentially a “one stop shop,” universal access model for young people and families experiencing early stage mental and substance use disorders. Some early literature and data on the headspace model has been published (McGorry, 2007b; McGorry, Bates, & Birchwood, 2013; McGorry et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2012). Research data gathered from these sites indicate that 38% of the patients meet the UHR criteria (Purcell et al., 2015).

2 | STUDY RATIONALE

The current study is a programme of translational research with two linked elements. The first element is designed to create new knowledge and skills for intervening in the early clinical stages of psychotic disorders. The heterogeneity of the UHR stage of illness means that individualized “adaptive” treatment policies are required. Some patients will respond while others will not to the same intervention type, intensity or duration. Other reasons in support of adaptive and sequential approaches include the need for sample enrichment, changing responsiveness linked to stage of illness, presence of comorbidities and the high risk of relapse even when initial remission has been achieved (Fusar-Poli et al., 2013). Creating an evidence base fit for implementation and for subsequent clinical translation requires a trial methodology which experimentally evaluates interventions via multistage designs, and which builds upon methods intended for the analysis of naturalistically observed strategies. A clinical trial design innovation, the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART), used in several recent large scale studies in psychiatry to develop an evidence base to support adaptive clinical care, is a good fit with the clinical staging model, and is ideal for the current study (Bhatt & Mehta, 2016). SMART designs involve multiple intervention stages that correspond to the critical decisions involved in adaptive interventions. Adaptive interventions are interventions in which the type or dosage of the intervention is individualized on the basis of patient characteristics or clinical presentation and then are repeatedly adjusted over time in response to patient progress (Bhatt & Mehta, 2016; Lei, Nahum-Shani, Lynch, Oslin, & Murphy, 2012). Interventions can also be tailored at critical decision points according to response or other patient characteristics such as specific biomarker changes or comorbidity, and also patient preference (Lavori et al., 2001).

SMART trials have been implemented in a number of fields, beginning in cancer research (Joss et al., 1994; Stone et al., 1995; Tummarello et al., 1997). Recently concluded SMART trials include the CATIE trial of treatments for schizophrenia (Stroup et al., 2003), Phase II trials at University of Texas MD for treating cancer (Thall et al., 2007), the ExTENd trial of treatments for alcohol dependence (EXTEND, 2005), and a SMART study of treatments for children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; see Lei et al., 2012 for review). Trials currently in the field include a SMART for nonverbal children with autism (CC-NIA, 2009), a SMART concerning behavioural interventions for drug-addicted pregnant women (HOME II, 2010) and a SMART for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (National Institute of Health, 2010). While adaptive trial designs add complexity to trial design and the statistical methods required, they will often provide greater statistical power and have more direct implications for real-world clinical decision making than RCTs due to the sequence of interventions based on patient response (Bhatt & Mehta, 2016).

The second element involves the processing of this emerging new evidence and adapting and translating this to key parts of the United States (US) healthcare system (the study is funded through the National Institute of Health [NIH]). We will conduct a series of focus groups with key stakeholders recruited from across the United States: (1) consumers, (2) families, (3) mental health and primary care clinicians, (4) local and national public health leadership; (5) private payer leadership; (6) public and private programme management. Each group will identify potential challenges and solutions to implement the model in public and private healthcare settings, focused on the following topics: diagnosis, assessment and eligibility, services reimbursement, prescribing issues and reimbursement, workforce training and sustainability, specialty services vs. integration, staged intervention algorithms, and cultural acceptability and adaptation. The resulting suggestions will be integrated and applied to the design of a feasibility study of open-label use of the staged treatment model in a university-based early psychosis specialty care clinic. Suggestions regarding adaptation might include guidelines for billing treatments in both public and private healthcare settings or adaptation of the model if all elements cannot be billed (eg, case management vs. therapy for private insurance).

3 | STUDY AIMS

The main study aim is to test outcomes of UHR patients, primarily functional outcome, in response to a sequential intervention strategy consisting of support and problem solving (SPS), CBCM and antidepressant medication. A secondary aim is to test biological and psychological variables that moderate and mediate response to this sequential treatment strategy.

3.1 | Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1. In Step 1 we hypothesize that 50% of participants (n = 500) will respond to the open label SPS intervention. This prediction is based on modelling of response rate achieved over 6 weeks in a previous RCT we conducted in the UHR population. (McGorry, Nelson, et al., 2013)

Hypothesis 2a In Step 2 (n = 200), we hypothesize that there will be a significantly better response (on the primary outcome of functioning) to CBCM than to SPS. This prediction is based on the evidence to date for the efficacy of CBT in the UHR population.

Secondary hypotheses for Step 2 are as follows:

In the CBCM group, baseline cognitive biases and vulnerabilities will predict response and outcome (H2b), and those with better outcome and responders will show a significantly greater change on these variables than those with worse outcome (H2c) and non-responders (H2d). These predictions are based on the assumption that CBT engages and treats psychological mechanisms (cognitive biases and vulnerability to stress) that may drive the onset of psychosis in a subset of UHR patients.

Hypothesis 3 In Step 3 (estimated n = 80), antidepressants will result in a significantly better outcome and greater response than placebo. This hypothesis is based on existing naturalistic evidence for the efficacy of anti-depressants in the UHR population. The fast-fail subgroup (see below) is a naturalistic phase and no specific hypothesis is advanced.

Hypothesis 4 For the relapse prevention arm of the study extending over a period from 6 weeks after the start through to the end of the first year of the study, depending on the point of entry, we hypothesize that those receiving SPS will show a significantly reduced rate of relapse compared to the monitoring only group. This prediction is based on the assumption that regular supportive psychotherapy may result in better outcome than simple monitoring in a subset of UHR patients.

4 | STUDY OBJECTIVES

4.1 | Primary objective

To test the effect of a sequential treatment approach consisting of SPS/SPS and SPS/CBCM on functioning levels of UHR patients 6 months post baseline (end of Step 2).

4.2 | Secondary objectives

To test the effect of a sequential treatment approach consisting of SPS, CBCM and antidepressant medication on functioning levels of UHR patients 12 months from baseline (end of Step 3).

To test the effect of a sequential treatment approach consisting of SPS, CBCM and antidepressant medication on transition to psychotic disorder by 12 months and 24 months from baseline.

To test the effect of a sequential treatment approach on UHR status (maintenance vs remission) 1.5 months, 6 months, 12 and 24 months from baseline.

To test the effect of a sequential treatment approach in UHR patients on level of psychiatric symptomatology, including positive psychotic symptoms, negative psychotic symptoms and depressive symptoms 6 months, 12 months and 24 months from baseline.

To test relapse rates (to UHR+ status) in the relapse prevention/ responder arm of the trial (SPS v monitoring) during the first 12 months.

4.3 | Exploratory objectives

The study aims to also explore whether there is a relationship between treatment response and specific patient profiles. In the subset of responders to a specific intervention, such as CBCM or antidepressants, the study will examine whether it is likely that the treatment was effective due to the proposed putative mechanisms (cognitive biases and neuroprotection). Psychological variables, inflammatory and oxidative stress, as well as related biomarkers will be measured at baseline, entry and exit from steps two and three and test whether these variables moderate or mediate response to treatment. The study will also investigate whether response to SPS or CBCM in Step 2 is mediated/moderated by degree of therapeutic alliance (quality of therapeutic relationship) between the participant and clinician. The study will also investigate whether SSRIs have any impact on inflammatory and/or oxidative stress biomarkers. Based on the background material reviewed above, we will also examine whether neurocognition, neuroimaging, CSF complement proteins and genetic variables predict outcome (persistent attenuated psychotic symptoms, transition to psychosis, poor functioning) and moderate/mediate response to treatment.

5 | STUDY DESIGN

This is a SMART. Participants who are classified as non-responders at the end of a Step will graduate to the next stage of intervention, while responders are offered entry to a maintenance/relapse prevention arm in which modest psychosocial care is compared in a randomized design with monitoring alone throughout the first 12 months of the study. A “fast fail” feature is included in Step 3 if the participant deteriorates or fails to show improvement. This consists of dose enhancement and entry to a personal choice/shared decision-making treatment option.

Research Assistants (RAs) conducting the clinical assessments will be blind to treatment allocation (Step 2: single-blind). Step 3 of the study incorporates a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled stage of the study. The study design is represented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Staged Treatment in Early Psychosis (STEP) study design

The design consists of 3 steps:

-

Step 1: Open-label Support & Problem Solving (SPS): “Open-label” SPS will be provided to all participants. A minimum of 3 sessions will be provided within a 6-week period. We expect this initial step will produce resolution of the current clinical phenotype in around 50% of participants, and thereby enrich the remaining sample for psychosis risk and functional impairment for randomisation in subsequent steps (Fusar-Poli & Van Os, 2013; Simon et al., 2013). We also expect this to help retention of participants as drop outs have tended to occur early in previous UHR trials (McGorry, Nelson, et al., 2013). Participants who respond to Step 1 will be randomized to SPS monthly sessions v Monitoring at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post entry to Step 1.

Monitoring will consist of the RA conducting a research assessment in addition to the clinician making contact with the participant in order to monitor mental state and risk and to assess whether there has been any mental health deterioration that would indicate a need for change in clinical management.

Step 2: CBCM vs SPS: Participants who do not respond (estimated at 50%) to Step 1 will be randomized to one of two treatment groups for 4.5 months: A more intensive psychosocial intervention (cognitive behavioural case management: CBCM) vs SPS. This design will test the potential benefit of a more intensive psychosocial intervention compared to extending the more basic intervention provided in Step 1 (SPS). It is possible that non-responders to Step 1 (6 weeks of SPS) have simply not received the SPS intervention for long enough (ie, the “dose” of SPS has not been sufficient to achieve symptom response and functional improvement). Extending SPS to a total of 6 months duration in Step 2 will test this possibility, as well as the potential benefit of introducing a more intensive psychotherapy in the form of CBCM. This step will test an intervention that targets a key putative mechanism for psychosis vulnerability and risk: the psychological mechanism of dysfunctional cognitive biases.

Step 3 CBCM + SSRIs vs CBCM + Placebo: The estimated 50% who do not respond by the end of Step 2 (Addington et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2013) will be randomized to antidepressant medication or placebo, in addition to CBCM, for a further 6-month period. Randomisation will be stratified based on depression scores (MADRS total score <21 or ≥21). This stage will test whether antidepressant medication in addition to CBCM contributes to improving the outcome of those who have failed to respond to previous interventions. It is appropriate to reserve antidepressants for this third step in view of their higher risk of adverse effects. By stratifying by depression at this stage of randomisation, we will be able to ascertain the impact of antidepressant medication on outcome in this population in relation to intensity of depressive symptoms, which will have direct implications for clinical decision-making as well as shed light on the possible mechanisms underlying the benefit of antidepressant medication for this patient group.

“Fast fail” in Step 3: Step 3 will incorporate a “fast fail” feature such that if patients deteriorate or have not responded after 12 weeks of this third step of the study, they will be offered the option of:

Continuing as randomized

Increasing the dosage of antidepressant medication/placebo or

Continuing the antidepressant or placebo with the addition of Omega-3 fatty acids or low dose antipsychotic medication chosen via a shared decision-making approach.

Responders

All responders during Steps 1 and 2 will be randomized at the end of each step to monthly SPS sessions or simple monitoring at 3 monthly intervals (Response to Step 1; 6, 9 and 12 months; Response to Step 2: 9 and 12 months) to assess whether such responses can be sustained. All relapsing participants at any stage and all non-responders at the 12 month point will be reassessed and offered “treatment as usual” via headspace and Orygen.

Rescue

A safety net or “rescue” strategy is built into the study design from Step 1 through to the end of Step 3 where participants whose psychotic symptoms worsen to the point of full threshold psychosis, or who develop acute mania, or sustained aggressive or suicidal risk as defined using the CAARMS are withdrawn entirely from the study and treated according to clinician’s choice, typically with antipsychotic or antidepressant medication, either as inpatients or with intensive community care and with full evidence-based psychosocial care.

Response

The definition of response is as follows:

The Global Rating Scale or the Frequency score need to be less than 3 for all of the four positive symptoms (Unusual Thought Content, Non-Bizarre Ideas, Perceptual Abnormalities and Disorganised Speech) and

There is an improvement of at least 5 points in Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) compared with baseline or the SOFAS score is at least 70.

The response status will be determined using the “current” ratings of CAARMS and will be determined at weeks 4, 6, 12, 24, 36, 52. These current ratings are based on the patients’ experience over the last fortnight and are for the four positive symptoms only.

The definitions for a responder at the different time points are as follows:

A responder at the end of Step 1 is one who shows a response at both weeks 4 and 6.

A responder at the end of Step 2 is one who shows a response at both weeks 12 and 24.

A responder at week 36 is one who shows a response at week 36 (for the “fast fail” option).

Non-response

All participants who do not meet the “response” criteria (and who have not yet made a transition to psychosis).

All participants will be closely monitored for adverse events and concomitant medication use throughout the study.

5.1 | Study setting

The sites for this trial will be 4 youth mental health services (head-space centres) funded through the Commonwealth Government of Australia and the PACE clinic, a specialized UHR research clinic that has two decades of innovation, clinical and research experience with this group of patients and their families (Phillips et al., 2002; Yung & Nelson, 2011; Yung et al., 1996). If recruitment rate is behind target, recruitment at additional headspace centres will be considered.

5.2 | Study duration

The controlled intervention component of the study is of 12 months duration. Participants will be followed up with research assessments up to 24 months post-baseline.

5.3 | Inclusion criteria

A participant will be considered eligible for inclusion in this study only if all of the following criteria apply:

Age 12–25 years (inclusive) at entry.

Ability to speak adequate English (for assessment purposes).

Ability to provide informed consent.

Meeting one or more UHR for psychosis groups (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Operationalized UHR intake criteria

| 1. Group 1: Vulnerability Group |

| Family history of psychosis in first degree relative OR Schizotypal Personality Disorder (as defined by DSM IV) in identified patient |

| AND |

| Drop in Functioning: |

| Recency: Change in functioning occurred within last year |

| Impact: SOFAS score at least 30% below previous level of functioning and sustained for at least one month. |

| OR |

| Sustained low functioning: |

| Recency: For the past 12 months or longer |

| Impact: SOFAS score of 50 or less. |

| 2. Group 2: Attenuated Psychotic Symptoms Group |

| 2a) Subthreshold intensity: |

| Intensity: Global Rating Scale Score of 3–5 on Unusual Thought Content subscale, 3–5 on Non-Bizarre Ideas subscale, 3–4 on Perceptual Abnormalities subscale and/or 4–5 on Disorganised Speech subscales of the CAARMS |

| Frequency: Frequency Scale Score of 3–6 on Unusual Thought Content, Non-Bizarre Ideas, Perceptual Abnormalities and/or Disorganised Speech subscales of the CAARMS |

| Duration: symptoms present for at least one week |

| Recency: symptoms present in past year |

| 2b) Subthreshold frequency: |

| Intensity: Global Rating Scale Score of 6 on Unusual Thought Content subscale, 6 on Non-Bizarre Ideas subscale, 5–6 on Perceptual Abnormalities subscale and/or 6 on Disorganised Speech subscales of the CAARMS |

| Frequency: Frequency Scale Score of 3 on Unusual Thought Content, Non-Bizarre Ideas,, Perceptual Abnormalities and/or Disorganised Speech subscales of the CAARMS |

| Recency: symptoms present in past year |

| 3. Group 3: BLIPS Group |

| Intensity: Global Rating Scale Score of 6 on Unusual Thought Content subscale, 6 on Non-Bizarre Ideas subscale, 5 or 6 on Perceptual Abnormalities subscale and/or 6 on Disorganised Speech subscales of the CAARMS |

| Frequency: Frequency Scale Score of 4–6 on Unusual Thought Content, Non-Bizarre Ideas, Perceptual Abnormalities and/or Disorganised Speech subscales |

| Duration: Symptoms present for less than one week and spontaneously remit on every occasion. |

| Recency: symptoms present in past year |

Young people seeking help via headspace centres will be screened using a standardized clinical assessment and the Prodromal Questionnaire-16 (PQ-16; Ising et al., 2012). Those who score 6 or more positive symptoms on the PQ-16 will be assessed using the CAARMS (Yung et al., 2005) and SOFAS (Goldman, Skodol, & Lave, 1992) to determine UHR status.

5.4 | Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Exclusion criteria

|

| Previous or current use of antipsychotic or antidepressant medication is not an exclusion criterion. In the case of current antipsychotic or antidepressant use, medication will be tapered and ceased at entry to the study. |

Potential participants who meet any of the following criteria will not be eligible for participation in this study:

5.4.1 | Participant discontinuation criteria

A participant will be considered “discontinued” from the study in cases where the study treatment is ceased. If appropriate, participants will be invited to continue in the study assessments in accordance with the study schedule, even though they are no longer receiving study treatment.

A participant will be discontinued from the study intervention in the following situations:

-

1

Serious adverse events at Investigator discretion.

-

2

Pregnancy during Step 3 (which involves antidepressant medication).

-

3

Severe non-compliance to protocol as judged by the Investigator.

-

4

At the Investigator’s discretion.

After consultation between the treating doctor and the study investigators, participant will also be discontinued from the study in the case of:

-

5

Transition to psychosis or mania. Transition is operationally defined via the CAARMS, as in previous studies (Yung et al., 2005), as positive psychotic symptoms occurring every day for 1 week or longer. A transition to full threshold mania will also mean that the participant is stopped since mood stabilizers will be administered.

-

6

Participants who have sustained risky levels of aggression or suicidality associated with their psychotic symptoms (or otherwise) at one of the follow-up assessments. Sustained levels of aggression is defined as a CAARMS 5.4 scale score of 6 sustained over the past 2 weeks and sustained levels of suicidality as a CAARMS 7.3 scale score of 6 sustained over the past 2 weeks.

These cases may be offered antipsychotic or antidepressant medication as inpatients or via intensive community care, as per early psychosis guidelines (Early Psychosis Writing Group, 2010; IEPA Writing Group, 2005). This constitutes rescue treatment.

5.5 | Visits and assessments

The schedule of assessments is shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Schedule of assessments and endpoint measures

| Visit number Intervention administered |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 (1.5 months) | Step 2 (4.5 months) | Step 3 (6 months)a | Follow upa,b | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Day -21 to Day 1 | Month 1–1.5 | Month 3a | Month 6a | Month 9 | Month 12 | Month 18 | Month 24 | ||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Screening (Day -21 to Day 1) | Baseline (Day 1) | Week 4c,d | Week 6c,d | Week 12c,d | Week 24c,d | Week 25c,d | Week 36c,d | Week 52c | Week 78c | Week 104c | |

| SPSe | SPS V CBCMf | CBCM + SSRI V CBCM + Placebof |

|||||||||

| Assessments | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Informed consent | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteriag | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Demographics | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Medical historyg | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Pregnancy (blood) | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Randomisation | X | X | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Safety | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Clinical bloods (haematology, biochemistry) | X | X | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Physical examination | X | X | X | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Adverse eventsh | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

|

| |||||||||||

| Concomitant med. review | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

|

| |||||||||||

| Psychopathology | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| PQ-16 | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| SCID_5 | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| SCID_IV PD | X | X | X | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| CAARMSk | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

|

| |||||||||||

| BPRS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| SANS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| MADRS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| FHI | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| ASSIST | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| DACOBSi | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| SQUEASE | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| CTQi | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Effects of psychological therapy scale (self-report) | X | X | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Working alliance inventory (client self-report) | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Working alliance inventory (clinician self-report) | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Functioning & quality of life | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| SOFAS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Global functioning: Social & roles scales | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| AQoL-8D | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Biologicalj | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Research bloods (inflammatory markers, oxidative stress, lipid metabolism) | X | X | X | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Genetic sample (blood) | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Neurocognition (BACS and BLERT)j | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Neuroimaging (MRI)j | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)j,l | X | X | |||||||||

Abbreviations: BACS, Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; BLERT, Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; MRI, Structural and functional MRI and Diffusion Tensor Imaging.

All follow-up visits for responders are to contain the same assessments as the corresponding non-responders progressing through Steps 2 and 3.

These assessments/visits done by all participants (including Step 1 and Step 2 responders)

Study visits 3–11 have a window of ±7 days

Data for these study visits can be captured retrospectively at the proceeding visit

≥ 3 SPS sessions over 6 weeks (1.5 months)

Weekly sessions or as clinically indicated with minimum of 6 sessions.

Assessments performed by a medical doctor and all participants will be medically reviewed by the end of Step 1.

Participants will also have regular (ideally weekly-fortnightly) contact with their treating team (case managers and/or psychiatrist), during which risk will be monitored.

Self-reports.

Optional components only to be conducted in participants consenting accordingly.

The full CAARMS will be administered across all study visits as indicated, with the exception of the screening visit; for which only the positive symptoms component of CAARMS will be administered.

The CSF collection may be conducted at two time points. The first sample will be collected during the middle of Step 2, and the second sample (optional) will typically occur at Week 52 or when the client ceases the on study participation, that is, if they are discontinued or withdraw.

6 | STUDY INTERVENTIONS

6.1 | Support and problem solving

SPS consists of basic supportive counselling and problem solving strategies delivered within a positive psychology framework. This is a minimal-level “treatment as usual” intervention for this group. Sessions will be weekly-fortnightly and of 30–50 minutes duration. Formal psychotherapy is not included in this intervention. SPS has proven safe, engaging and effective for the wider range of early diagnostic presentations in our primary care platform, headspace (Parker et al., 2011).

6.2 | Cognitive-behavioural case management

CBCM consists of CBT embedded within case management, as successfully developed and implemented in our previous studies (The PACE Manual Writing Group, 2012). The CBT consists of four modules addressing attenuated psychotic symptoms, stress management, negative symptoms/depression and other comorbidity. All modules consist of psychoeducation, behavioural strategies/experiments and cognitive restructuring. There is preliminary evidence that yoga and mindfulness may be of value in early psychosis patients (Chen et al., 2014) and have therefore been incorporated into the current treatment package, delivered in a group setting. The treatment approach is modular and based on shared formulation with the individual client; it therefore does not prescribe which module should be delivered or for how long. The treatment components are provided within a case management framework addressing practical issues. The standard will be to deliver CBCM sessions weekly, but frequency of sessions will be flexible depending on the participant’s needs. Sessions will be 30–50 minutes in duration. A minimum of 6 sessions will be provided.

6.3 | Medications

Antidepressants (SSRIs) in Step 3: Oral capsules of fluoxetine 20–40 mg or matched placebo daily for 6 months. Participants will commence on 1 capsule of fluoxetine 20 mg or 1 capsule of the placebo pill. The medication can be increased to fluoxetine 40 mg daily (or 2 placebo capsules) if there has been a poor clinical response after the first 6 weeks of Step 3.

Omega-3 fatty acids as “fast fail” option in Step 3 (12 weeks into Step 3): 2.8 g/d of marine fish oil containing approximately 1.4 g eicosapentaoic acid (EPA/DHA) in 4 × 0.700 g capsules.

Antipsychotic medication as “fast fail” option in Step 3 (12 weeks into Step 3): Quetiapine 50–300 mg/d or Aripiprazole 10–30 mg/d.

7 | CONCOMITANT MEDICATION AND THERAPIES

All psychiatric treatments administered to 24 months will be recorded.

7.1 | Procedures for monitoring compliance with interventions

SSRIs

During Step 3 participants’ compliance with study medication will be recorded via pill count. Compliance will also be monitored using a mobile application developed by our group (“Smartphone Ecological Momentary Assessment”; SEMA). This mobile phone application will consist of a system that prompts participants every evening to input their medication use (number of capsules taken) over the previous day.

SPS and CBCM

Sessions will be audiotaped and rated by blinded raters in order to assess fidelity to these psychological interventions. Fidelity will also be monitored by therapists rating their own sessions on a checklist of therapeutic interventions. Any additional psychosocial interventions delivered will also be documented.

7.2 | Statistical analysis

The primary analysis will be to compare the two Step 2 treatments on the 6-month Global Functioning: Social and Role Scale score (Cornblatt, Auther, et al., 2007) using analysis of covariance with the baseline Global Functioning: Social and Role Scale score as the covariate. The treatment options in Steps 2 and 3 correspond to 4 treatment regimes for the non-responders. Comparing fluoxetine and placebo from Step 3 is equivalent to collapsing these regimes into two groups. A secondary analysis will be to compare these two groups using ANCOVA in terms of 12-month Global Functioning: Social and Role Scale score. Comparing the different treatment regimes will also be considered. Survival analysis will also be used for comparison of transition rates. Other secondary outcome measures at the various time points will be examined using appropriate techniques such as ANCOVA, chi-square tests and multi-level modelling. Potential confounders and predictors will also be taken into account. If the amount of missing values is non-trivial, then imputation techniques such as multiple imputation will be considered. Intention to Treat (ITT) analysis will be conducted.

7.3 | Sample size and power

The study is powered on the primary aim of comparing 6-month functional outcome between the two treatment groups in Step 2. Assuming a 50% non-response rate in Step 1, an entry sample size of 500, a drop-out rate of 20% and hence a step 2 sample size of 200, we will be able to detect a fairly small effect size (0.18 in a parallel cell design) with a power of 80% and significance level of .05 by the end of Step 2. Recent data indicates that approximately 38% of young people seen at headspace meet UHR criteria, which means that approximately 2000 patients per annum will be eligible for the study. A two-year recruitment period means that 500 participants would need to be recruited from a pool of 4000 patients (12.5%). It is standard for SMART trials to be powered on a single stage or aspect of a multi-staged design (Lei et al., 2012). Nevertheless, a 50% non-response rate in Step 2 and 20% drop-out rate will result in n = 80 in Step 3, which will be sufficient to detect a clinically important medium effect size (0.29) for comparing the two Step 3 interventions with a power of 80% and significance level of .05.

8 | SUMMARY

In summary, this study’s sequential multi-stage design is intended to produce evidence to guide a stepwise clinical approach to treatment of UHR patients and reduction of risk for psychosis and other deleterious clinical and/or functional outcomes. The study will also collect data on key biomarkers and other mechanisms potentially underpinning risk, which may ultimately be used to adapt and personalize treatment. Major recent service reforms and expansions in Australia have enabled our research centre to access much larger clinical samples through which we can make a crucial contribution to assembling an evidence base that, with the assistance of the US investigators, will be translatable to US health care, and other settings worldwide with the goal of reducing the enormous human, social and economic costs of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

References

- Addington J, Cornblatt BA, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, … Heinssen R. At clinical high risk for psychosis: Outcome for nonconverters. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):800–805. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Jimenez M, Gleeson JF, Henry LP, Harrigan SM, Harris MG, Killackey E, … McGorry PD. Road to full recovery: Longitudinal relationship between symptomatic remission and psychosocial recovery in first-episode psychosis over 7.5 years. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(3):595–606. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amminger GP, Schafer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Cotton SM, Harrigan SM, … Berger GE. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):146–154. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechdolf A, Wagner M, Ruhrmann S, Harrigan S, Putzfeld V, Pukrop R, … Klosterkötter J. Preventing progression to first-episode psychosis in early initial prodromal states. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200(1):22–29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.066357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HE, Nieman DH, Dingemans PM, van de Fliert JR, De Haan L, Linszen DH. Verbal fluency as a possible predictor for psychosis. European Psychiatry. 2010;25(2):105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, Dean OM, Giorlando F, Maes M, … Malhi GS. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: Focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35(3):804–817. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Ohlenschlaeger J, le Quach P, … Nordentoft M. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness: The OPUS trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):762–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton O, McClung CA, Dileone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, … Nestler EJ. Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science. 2006;311(5762):864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1120972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt DL, Mehta C. Adaptive designs for clinical trials. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(1):65–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitanihirwe BK, Woo TU. Oxidative stress in schizophrenia: An integrated approach. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35(3):878–893. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgwardt SJ, McGuire PK, Aston J, Gschwandtner U, Pflüger MO, Stieglitz R, … Riecher-Rössler A. Reductions in frontal, temporal and parietal volume associated with the onset of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2008;106:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer W, Francey S, Wood S, Jackson H, Pantelis C, Phillips L, … McGorry PD. Memory impairments identified in people at ultra-high risk for psychosis who later develop first-episode psychosis. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(1):71–78. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer WJ, Wood SJ, Phillips LJ, Francey SM, Pantelis C, Yung AR, … McGorry PD. Generalized and specific cognitive performance in clinical high-risk cohorts: A review highlighting potential vulnerability markers for psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(3):538–555. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Taylor A, Murray RM, Poulton R. Evidence for early-childhood, pan-developmental impairment specific to schizophreniform disorder: Results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(5):449–456. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.5.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor-Graae E. The contribution of social factors to the development of schizophrenia: A review of recent findings. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52(5):277–286. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CC-NIA. Developmental and augmented intervention for facilitating expressive language (CC-NIA) 2009 [Internet]. Retrieved from http://clinical-trials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01013545?term=kasari&rank=5.

- Chen EYH, Lin J, Lee EHM, Chang WC, Chan SKW, Hui CLM. Yoga exercise for cognitive impairment in psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia Research. 2014;153(Supplement 1):S26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Hasanat KA, Bebchuk JM, Moore GJ, Glitz D, Manji HK. Regulation of signal transduction pathways and gene expression by mood stabilizers and antidepressants. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61(5):599–617. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Auther AM, Niendam T, Smith CW, Zinberg J, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33(3):688–702. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, Correll CU, Auther AM, Nakayama E. The schizophrenia prodrome revisited: A neuro-developmental perspective. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29(4):633–651. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, Olsen R, Auther AM, Nakayama E, … Correll CU. Can antidepressants be used to treat the schizophrenia prodrome? Results of a prospective, naturalistic treatment study of adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68(4):546–557. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig TKJ, Garety PA, Power P, Rahaman N, Colbert S, Fornells-Ambrojo M, Dunn G. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: Randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. British Medical Journal. 2004;329(v):1067. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38246.594873.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M, Reichenberg A, Rabinowitz J, Weiser M, Kaplan Z, Mark M. Behavioral and intellectual markers for schizophrenia in apparently healthy male adolescents. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1328–1335. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd S, Maes M, Anderson G, Dean OM, Moylan S, Berk M. Putative neuroprotective agents in neuropsychiatric disorders. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2013;42:135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early Psychosis Writing Group. Australian clinical guidelines for early psychosis. 2. Melbourne, Australia: Orygen Youth Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eastvold AD, Heaton RK, Cadenhead KS. Neurocognitive deficits in the (putative) prodrome and first episode of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;93(1–3):266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EU-GEI. Schizophrenia aetiology: Do gene-environment interactions hold the key? Schizophrenia Research. 2008;102(1):21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EXTEND. Managing alcoholism in people who do not respond to naltrexone (EXTEND) 2005 [Internet]. Retrieved from http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00115037?term=oslin&rank=8.

- Fineberg AM, Ellman LM. Inflammatory cytokines and neurological and neurocognitive alterations in the course of schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;73(10):951–966. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatow J, Buckley P, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French P. Model-driven psychological intervention to prevent onset of psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 2002;106(413):18. [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, Borgwardt S, Kempton MJ, Valmaggia L, … McGuire P. Predicting psychosis: Meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, Addington J, Riecher-Rossler A, Schultze-Lutter F, … Yung A. The psychosis high-risk state: A comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(1):107–120. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Frascarelli M, Valmaggia L, Byrne M, Stahl D, Rocchetti M, … McGuire P. Antidepressant, antipsychotic and psychological interventions in subjects at high clinical risk for psychosis: OASIS 6-year naturalistic study. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(6):1327–1339. doi: 10.1017/S003329171400244X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Valmaggia L, McGuire P. Can antidepressants prevent psychosis? Lancet. 2007;370(9601):1746–1748. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61732-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Van Os J. Lost in transition: Setting the psychosis threshold in prodromal research. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2013;127(3):248–252. doi: 10.1111/acps.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety PA, Craig TK, Dunn G, Fornells-Ambrojo M, Colbert S, Rahaman N, … Power P. Specialised care for early psychosis: Symptoms, social functioning and patient satisfaction: Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188:37–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety PA, Freeman D. Cognitive approaches to delusions: A critical review of theories and evidence. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;38:113–154. doi: 10.1348/014466599162700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Freeman D, Bebbington PE. A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31(2):189–195. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner B, Pariante CM, Wood SJ, Velakoulis D, Phillips L, Soulsby B, … Pantelis C. Pituitary volume predicts future transition to psychosis in individuals at ultra-high risk of developing psychosis. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58(5):417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman H, Skodol A, Lave T. Revising Axis V for DSM-IV: A review of measures of social functioning. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:1148–1156. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann JA, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Yung AR, Lin A, Wood SJ, … Nelson B. Declining transition rates to psychotic disorder in “ultra-high risk” clients: Investigation of a dilution effect. Schizophrenia Research. 2016;170(1):130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOME II. Reinforcement-based treatment for pregnant drug abusers (HOME II) 2010 [Internet]. Retrieved from http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01177982?term=jones+pregnant&rank=9.

- Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: Version III—The final common pathway. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35(3):549–562. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton P, Taylor PJ. Cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2013;44(3):1–20. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IEPA Writing Group. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187(supplement 48):s120–s124. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising HK, Kraan TC, Rietdijk J, Dragt S, Klaassen RM, Boonstra N, … van der Gaag M. Four-year follow-up of cognitive behavioral therapy in persons at ultra-high risk for developing psychosis: The Dutch Early Detection Intervention Evaluation (EDIE-NL) Trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2016;42(5):1243–1252. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising HK, Veling W, Loewy RL, Rietveld MW, Rietdijk J, Dragt S, … van der Gaag M. The validity of the 16-item version of the Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-16) to screen for ultra high risk of developing psychosis in the general help-seeking population. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38(6):1288–1296. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job DE, Whalley H, Johnstone EC, Lawrie SM. Grey matter changes over time in high risk subjects developing schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2005;25:1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joss RA, Alberto P, Bleher EA, Ludwig C, Siegenthaler P, Martinelli G, … Senn HJ. Combined-modality treatment of small-cell lung cancer: Randomized comparison of three induction chemotherapies followed by maintenance chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy to the chest. Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) Annals of Oncology. 1994;5(10):921–928. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur T, Cadenhead KS. Treatment implications of the schizophrenia prodrome. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 2010;4:97–121. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Shin NY, Jang JH, Kim E, Shim G, Park HY, … Kwon JS. Social cognition and neurocognition as predictors of conversion to psychosis in individuals at ultra high risk. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;130(1–3):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Miller BJ. Inflammation and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013;39(6):1174–1179. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Alpert J, Fava M, Kupfer DJ, … Trivedi M. Strengthening clinical effectiveness trials: Equipoise-stratified randomization. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50(10):792–801. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H, Nahum-Shani I, Lynch K, Oslin D, Murphy SA. A “SMART” design for building individualized treatment sequences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:21–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencz T, Smith CW, McLaughlin D, Auther A, Nakayama E, Hovey L, Cornblatt BA. Generalized and specific neuro-cognitive deficits in prodromal schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59(9):863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, Addington J, Miller T, Woods SW, … Breier A. Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis [see comment] American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):790–799. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P, Bates T, Birchwood M. Designing youth mental health services for the 21st century: Examples from Australia, Ireland and the UK. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;202(s54):s30–s35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P, van Os J. Redeeming diagnosis in psychiatry: Timing versus specificity. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):343–345. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD. Issues for DSM-V: Clinical staging: A heuristic pathway to valid nosology and safer, more effective treatment in psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007a;164(6):859–860. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD. The specialist youth mental health model: Strengthening the weakest link in the public mental health system. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007b;187(7 Suppl):S53–S56. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD. Early clinical phenotypes, clinical staging, and strategic biomarker research: Building blocks for personalized psychiatry. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):394–395. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Jackson HJ. Clinical staging of psychiatric disorders: A heuristic framework for choosing earlier, safer and more effective interventions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40(8):616–622. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Nelson B, Markulev C, Yuen HP, Schafer MR, Mossaheb N, … Amminger GP. Effect of omega-3 polyun-saturated fatty acids in young people at ultrahigh risk for psychotic disorders: The NEURAPRO randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(1):19–27. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Nelson B, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey SM, Thampi A, … Yung AR. Randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis: Twelvemonth outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):349–356. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Tanti C, Stokes R, Hickie IB, Carnell K, Littlefield LK, Moran J. Headspace: Australia’s National Youth Mental Health Foundation—Where young minds come first. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007;187(7):S68. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey S, Cosgrave EM, … Jackson H. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):921–928. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ. Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):315–336. doi: 10.1037/a0014708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael-Titus AT, Bains S, Jeetle J, Whelpton R. Imipramine and phenelzine decrease glutamate overflow in the prefrontal cortex—A possible mechanism of neuroprotection in major depression? Neuroscience. 2000;100(4):681–684. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, Mellor A, Kirkpatrick B. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: Clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70(7):663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AP. The interpretation of intrusions in psychosis: An integrative cognitive approach to hallucinations and delusions. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AP, editor. A casebook of cognitive therapy for psychosis. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AP, French P, Parker S, Roberts M, Stevens H, Bentall RP, Lewis SW. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33(3):682–687. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health. Sequential two-agent assessment in renal cell carcinoma therapy. 2010 [Internet]. Retrieved from http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01217931.

- Nelson B, Yuen HP, Lin A, Wood SJ, McGorry PD, Hartmann JA, Yung AR. Further examination of the reducing transition rate in ultra high risk for psychosis samples: The possible role of earlier intervention. Schizophrenia Research. 2016;174(1–3):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B, Yuen HP, Wood SJ, Lin A, Spiliotacopoulos D, Bruxner A, … Yung AR. Long-term follow-up of a group at ultra high risk (“Prodromal”) for psychosis: The PACE 400 Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(8):793–802. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niendam TA, Lesh TA, Yoon J, Westphal AJ, Hutchison N, Daniel Ragland J, … Carter CS. Impaired context processing as a potential marker of psychosis risk state. Psychiatry Research. 2014;221(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Petersen A, Thorup A, Ohlenschlaeger J, Krarup T, … Jorgensen P. The OPUS trial: A randomised multi-centre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for 547 -first-episode psychotic patients. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;70:31. [Google Scholar]

- Nordentoft M, Thorup A, Petersen L, Ohlenschlaeger J, Melau M, Christensen TO, … Jeppesen P. Transition rates from schizotypal disorder to psychotic disorder for first-contact patients included in the OPUS trial. A randomized clinical trial of integrated treatment and standard treatment. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;83(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RM, Windell D, Manchanda R, Harricharan R, Northcott S. Social support and functional outcomes in an early intervention program. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;140(1–3):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, Wood SJ, Suckling J, Phillips LJ, … McGuire PK. Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: A cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI study. The Lancet. 2003;361:281–288. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AG, Hetrick SE, Jorm AF, Yung AR, McGorry PD, Mackinnon A, … Purcell R. The effectiveness of simple psychological and exercise interventions for high prevalence mental health problems in young people: A factorial randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:76. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, Yuen HP, Ward J, Donovan K, Kelly D, … Yung AR. Medium term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra high risk of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;96(1–3):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LJ, Francey SM. Changing PACE: Psychological interventions in the prepsychotic phase. In: Gleeson JFM, McGorry PD, editors. Psychological interventions in early psychosis: A treatment handbook. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LJM, Leicester SBM, O’Dwyer LEB, Francey SMM, Koutsogiannis JMF, Abdel-Baki AMF, … McGorry PD. The PACE Clinic: Identification and management of young people at “ultra” high risk of psychosis. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2002;8(5):255–269. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukrop R, Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, Brockhaus-Dumke A, Klosterkötter J. Neurocognitive indicators for a conversion to psychosis: Comparison of patients in a potentially initial prodromal state who did or did not convert to a psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;92(1–3):116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell R, Jorm AF, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Amminger GP, … McGorry PD. Demographic and clinical characteristics of young people seeking help at youth mental health services: Baseline findings of the Transitions Study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2015;9(6):487–497. doi: 10.1111/eip.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riecher-Rössler A, Pflueger MO, Aston J, Borgwardt SJ, Brewer WJ, Gschwandtner U, Stieglitz RD. Efficacy of using cognitive status in predicting psychosis: A 7-year follow-up. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez V, Camarero J, Esteban B, Peter MJ, Green AR, Colado MI. The mechanisms involved in the long-lasting neuroprotective effect of fluoxetine against MDMA (‘ecstasy’)-induced degeneration of 5-HT nerve endings in rat brain. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2001;134(1):46–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]