Abstract

Objective

Ischemic heel ulcerations are generally thought to carry a poor prognosis for limb salvage. We hypothesized that patients undergoing infrapopliteal revascularization for heel wounds, either bypass or endovascular intervention, would have lower wound healing rates and amputation-free survival than patients with forefoot wounds.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed of patients who presented between 2006 and 2013 to our institution with ischemic foot wounds and infrapopliteal arterial disease and underwent either pedal bypass or endovascular tibial artery intervention. Data was collected on patient demographics, comorbidities, wound characteristics, procedural details, and postoperative outcomes, then analyzed by initial wound classification. The primary outcome was major amputation or death.

Results

398 limbs underwent treatment for foot wounds; accurate wound data was available in 380 cases. There were 101 bypasses and 279 endovascular interventions, with mean follow-up 24.6 and 19.9 months, respectively (P = .02). Heel wounds comprised 12.1% of the total with the remainder being forefoot wounds; there was no difference in treatment modality by wound type (P = .94). Of 46 heel wounds, 5 (10.9%) had clinical or radiographic evidence of calcaneal osteomyelitis. Patients with heel wounds were more likely to have diabetes mellitus (P = .03) and renal insufficiency (P = .004). 43.1% of wounds healed within one year, with no difference by wound location (P = .30). Major amputation rate at one year was 17.8%, with no difference by wound location (P = .81) or treatment type (P = .33). One-year and three-year amputation-free survival was 66.2% and 44.0% for forefoot wounds and 45.7% and 17.6% for heel wounds, respectively (P = .001). In a multivariate analysis, heel wounds and endovascular intervention were both predictors of death; however, there was significant interaction such that endovascular intervention was associated with higher mortality in patients with forefoot wounds (HR 2.25, P < .001) but not those with heel wounds (HR 0.67, P = .31).

Conclusions

Patients presenting with heel ulceration who undergo infrapopliteal revascularization are prone to higher mortality, despite equivalent rates of amputation and wound healing and regardless of treatment modality. These patients may benefit from an endovascular-first strategy.

1. Introduction

Critical limb ischemia carries a generally poor prognosis, with mortality rates as high as 40% at two years and amputation rates as high as 67% at four years [1–3]. While many of these patients have atherosclerotic disease present in multiple anatomic locations, those with tibial arterial disease are at particularly high risk of amputation [4]. Tibial disease is commonly associated with a number of medical comorbidities [4–7] which place these patients at increased risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality despite the treatment modality.

Non-healing ischemic ulcerations represent the late stages of peripheral arterial disease, and patients with such lesions are unlikely to avoid limb loss without revascularization [2]. Aspects of a wound, such as its size, depth, bone exposure, or clinically apparent infection, have long been known to have implications regarding the ability to heal the wound. The development of the Wound, Ischemia, and foot Infection (WIfI) classification system has enabled us to score ischemic foot wounds in a consistent manner [8]. A better understanding of the impact of these details allows us to identify those patients with the greatest need for operative revascularization [9].

The angiosome model and the importance of anatomic location of an ischemic foot wound has received considerable interest in contemporary literature, though not all studies show improved outcomes when angiosomes are targeted for open surgical bypass or endovascular intervention [10–13]. But in addition to the anatomic implications of a wound, there appear to be clinical implications as well. Heel ulceration is a poor prognostic indicator as it tends to occur in patients with prolonged immobility, which in turn may be a consequence of a severe comorbidity burden [14]. We hypothesized that, among patients with ischemic foot wounds and tibial arterial disease who undergo a revascularization procedure, patients with a heel wound are at greater risk of major amputation and death compared to patients with a forefoot wound and, due to the multifactorial nature of these wounds, are less likely to successfully heal their wounds after revascularization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Patient Selection

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of our work. All patients who presented to our institution between 2006 and 2013 with a lower extremity ischemic wound, were found to have atherosclerotic disease of the infrapopliteal arteries, and subsequently underwent a revascularization procedure were considered for inclusion. Patients were identified by a search of our electronic medical record (EMR). Anatomic lesions were identified by CT angiography or conventional angiography in all patients; physiologic parameters including ankle-brachial index (ABI) and toe pressure (TP) were measured in a subset of patients but were not considered in our patient selection.

Patients were included if they underwent either bypass to a pedal target (dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial, or plantar arteries) or endovascular intervention involving the tibial vessels (anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and/or peroneal arteries). Additional revascularization for more proximal disease (either surgical or endovascular) was noted but did not exclude patients from the study. Patients were excluded (1) if the wound was located above the ankle or if its location could not be determined accurately from the medical record; (2) if the operative report for the index procedure did not provide sufficient anatomic detail or the procedure was done at an outside institution; or (3) if no post-procedure follow-up data was available. In patients who received multiple tibial revascularization procedures in the same limb, only the index procedure was considered.

2.2 Data Sources

Patient data, including vascular laboratory testing and relevant imaging, was collected from the EMR. In addition to demographics, baseline patient characteristics included relevant comorbidities such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, renal impairment, known hypercoagulable state, smoking status, and a relevant medication history.

Wounds were identified from the EMR as either heel wounds or forefoot wounds. Patients with both heel and forefoot wounds were placed in the heel wound group. Wound images embedded into the EMR were also studied when available. The severity of all wounds was classified according to the Wound, Ischemia, foot Infection (WIfI) scoring system [8], which has been previously validated as a predictor of amputation in patients with infrapopliteal arterial disease [9]. Severity of heel wounds was additionally classified by the presence of calcaneal osteomyelitis, which was defined by either (1) radiographic evidence of osteomyelitis or (2) grossly exposed bone at the base of the wound. When available, specific wound data was included in the analysis.

2.3 Outcomes and Statistical Methods

Death or need for major amputation was the composite primary outcome. Death and amputation rates alone were investigated as secondary outcomes, as were primary, primary assisted, and secondary patency, and healing of the index wound. Minor amputation was not considered in our outcomes, as it is only definable in forefoot wounds. When a minor amputation was performed for a forefoot wound, the amputation incision was considered to be the index wound for analysis of healing after revascularization.

Data was compiled and organized using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), and statistical calculations were performed using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Baseline characteristics were compared using Student's t-tests (for continuous data) and Chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests (for categorical data). Equivalent nonparametric tests were used where appropriate for any data with highly skewed distributions. 30-day outcomes were analyzed by logistic regression. The remainder were treated as time-dependent, and Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards models were created for each outcome. Univariate predictors were assessed by the log-rank test (for categorical predictors) and univariate Cox regression analysis. Multivariate Cox regression models were constructed by backward stepwise elimination starting with all predictors that were significant or near-significant by univariate analysis. A critical P-value of 0.05 was used to define significance for all statistical tests. In all Kaplan-Meier curves, standard error was ≤10% at all time points in all groups shown.

3. Results

3.1 Study Cohort and Procedural Details

We identified a total of 417 limbs which underwent pedal bypass or endovascular tibial intervention in the context of a lower extremity wound and returned for at least one follow-up visit. Nineteen limbs had a wound located above the ankle and were excluded. Eighteen limbs had a wound whose location could not be identified in any documentation and were also excluded. The remaining 380 limbs comprised the cohort for our analysis. In this cohort, there were 46 (12.1%) heel wounds and 334 (87.9%) forefoot wounds. 101 (26.6%) patients underwent bypass and 279 (73.4%) underwent endovascular intervention. Wound location was not predictive of whether a patient was offered surgical bypass (P = .94). Mean follow-up was 24.6 months for patients who underwent bypass and 19.9 months for those who underwent endovascular intervention (P = .02).

Baseline characteristics by wound location are shown in Table I and were generally similar between the two groups. Patients with heel wounds were more likely to have diabetes mellitus (DM) (P = .028) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (P = .004) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) with dialysis dependence (P = .046). Nineteen percent of patients had undergone at least one prior open or endovascular procedure, with no difference between the two groups. When wounds were scored by the WIfI criteria, heel wounds were classified as more severe (P < .001), but the ischemia and foot infection scores were similar between groups. Among the heel wounds, 5 (10.9%) had clinical (exposed bone within the wound) or radiographic evidence (by X-ray or magnetic resonance imaging) of calcaneal osteomyelitis; all 5 patients underwent wound debridement with calcanectomy at the time of revascularization. ABI was unable to be calculated due to vessel non-compressibility in 65.3% of patients; toe pressures were not consistently recorded in this patient population.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics by wound location. Cell contents are expressed as either mean (standard deviation) or percentage depending on data type. WIfI: Wound, Ischemia, foot Infection.

| Baseline Characteristic | Forefoot wound N = 334 | Heel wound N = 46 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 72.9 (11.7) | 70.5 (12.2) | 0.20 |

| Male sex | 68.9% | 69.6% | 0.92 |

| White race | 85.6% | 78.3% | 0.19 |

| Hypertension | 88.3% | 95.7% | 0.133 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 59.0% | 45.7% | 0.087 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 77.3% | 91.3% | 0.028 |

| Coronary artery disease | 68.9% | 71.7% | 0.692 |

| Prior cerebrovascular accident | 22.5% | 32.6% | 0.129 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 16.2% | 17.4% | 0.833 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 44.3% | 67.4% | 0.004 |

| Dialysis dependence | 21.6% | 34.8% | 0.046 |

| Smoking (current or former) | 52.4% | 41.3% | 0.158 |

| Medications | |||

| Antiplatelet | 72.2% | 69.6% | 0.714 |

| Anticoagulant | 22.8% | 28.3% | 0.408 |

| Statin | 54.8% | 56.5% | 0.825 |

| Beta-blocker | 68.0% | 69.6% | 0.827 |

| Prior lower extremity revascularization | 19.2% | 17.4% | 0.774 |

| Open | 11.1% | 4.4% | 0.200 |

| Endovascular | 10.8% | 15.2% | 0.373 |

| WIfI wound score | |||

| 0 | 0% | 0% | |

| 1 | 24.2% | 2.2% | <0.001 |

| 2 | 65.8% | 37.0% | |

| 3 | 10.0% | 60.9% | |

| WIfI ischemia score | |||

| 0 | 16.1% | 12.5% | |

| 1 | 19.5% | 25.0% | 0.72 |

| 2 | 19.9% | 25.0% | |

| 3 | 44.5% | 37.5% | |

| WIfI foot infection score | |||

| 0 | 47.3% | 60.9% | |

| 1 | 27.9% | 17.4% | 0.32 |

| 2 | 23.9% | 21.7% | |

| 3 | 0.9% | 0.0% | |

Among patients who underwent bypass, the inflow artery was suprageniculate in 28.7% and infrageniculate in 71.3%. Bypass target was the dorsalis pedis artery or a tarsal branch in 73.3% and the posterior tibial or a plantar branch in 26.7%. Single-segment greater saphenous vein was used as the conduit in 72.3%, with the remainder being alternative autologous vein (24.8%) or prosthetic (3.0%). Two patients (2.5%) underwent concomitant endovascular intervention at a more proximal level. Seventy-nine percent of bypass patients were either initiated or maintained on antiplatelet agents post-procedure.

Among patients who underwent endovascular intervention, the anterior tibial artery was treated in 50.9%, posterior tibial artery in 35.1%, and peroneal artery in 51.6%. One tibial artery was treated in 68.5%, two in 25.5%, and all three in 6.1%. Endovascular treatment modalities included balloon angioplasty (99.3%), atherectomy (6.8%), and stenting (2.9%). Post-angioplasty dissection was noted in 8.6% of patients, which was treated by repeat angioplasty or stenting in 25% and observed in the remainder. Proximal concomitant endovascular intervention was performed in 44.8% of cases; one patient underwent femoral endarterectomy and one underwent a bypass more proximally. 88.9% of endovascular patients were either initiated or maintained on antiplatelet agents post-procedure.

3.2 30-Day Outcomes

30-day outcomes are summarized in Table II. Median length of hospital stay post-procedure was 4 days (range 0-42). As expected, hospital stay was longer for patients undergoing bypass (P < .0001), but there was no difference by wound location in the overall cohort (P = .89) or in the bypass group (P = .32). Overall 30-day mortality was 3.2%, with no difference between groups (P = .65). Major amputation rate at 30 days was also 3.2%, with no difference between groups (P = .65). There was a trend toward increased morbidity in patients with heel wounds, but no single outcome reached statistical significance. There was a near-significant association between heel wounds and discharge to a nursing facility rather than home (OR 1.75, 95% CI 0.92-3.31, P = .088).

Table II.

Perioperative outcomes by wound location. The final two outcomes are in-hospital outcomes while the remainder are 30-day outcomes. LOS: hospital length of stay.

| Outcome | Forefoot wound | Heel wound | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median LOS | 4 days | 4.5 days | 0.89 |

| Death | 3.0% | 4.3% | 0.63 |

| Major amputation | 3.0% | 4.3% | 0.63 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.2% | 4.3% | 0.13 |

| Acute kidney injury | 5.4% | 10.9% | 0.15 |

| Pneumonia | 2.4% | 6.5% | 0.13 |

| Ambulatory at discharge | 75.0% | 75.6% | 0.94 |

| Discharge to nursing facility | 26.9% | 39.1% | 0.088 |

3.3 Major Amputation-Free Survival

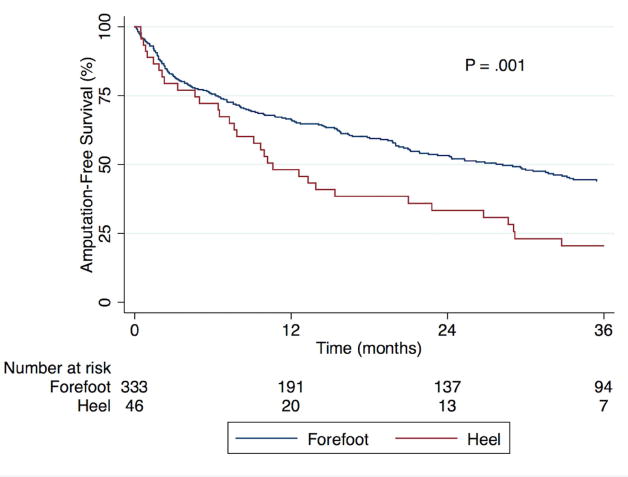

Overall major amputation-free survival (AFS) was 64.1% at one year and 40.9% at three years; there was an insufficient number of heel wounds at risk to study further time points. A Kaplan-Meier curve for AFS stratified by wound location is shown in Fig. 1. The survivor functions were statistically different with heel wound patients at higher risk (P = .001). One-year and three-year AFS was 66.3% and 43.8% for forefoot wounds and 48.1% and 20.8% for heel wounds, respectively. Univariate predictors of major amputation or death are shown in Table III, and included presence of a heel wound. Bypass was associated with improved AFS in our univariate analysis. Most comorbidities were associated with higher risk, particularly renal disease. DM, hyperlipidemia, and a former smoking history were found to be protective; current smoking was not a significant predictor. Procedural factors, such as the inflow or target vessel for a bypass or the number or identity of tibial vessels treated by endovascular intervention, and temporal trends were investigated but were not found to be predictors.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of major amputation-free survival stratified by wound location.

Table III.

Predictors of major amputation or death by univariate Cox regression analysis. DM: diabetes mellitus. CKD: chronic kidney disease. ESRD: end-stage renal disease. CAD: coronary artery disease. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Univariate Predictor | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heel wound vs. forefoot wound | 1.76 | 1.24 – 2.49 | 0.001 |

| Endovascular intervention vs. bypass | 1.86 | 1.33 – 2.60 | 0.0002 |

| Age (per year) | 1.02 | 1.01 – 1.03 | 0.006 |

| DM | 0.72 | 0.53 – 0.98 | 0.036 |

| CKD | 1.66 | 1.29 – 2.14 | 0.0001 |

| ESRD | 2.03 | 1.54 – 2.69 | <0.0001 |

| 0.65 | 0.50 – 0.83 | 0.0007 | |

| CAD | 1.32 | 0.99 – 1.76 | 0.054 |

| COPD | 1.88 | 1.37 – 2.58 | 0.0001 |

| Smoking | |||

| Former | 0.70 | 0.53 – 0.93 | 0.013 |

| Current | 0.93 | 0.64 – 1.37 | 0.72 |

A multivariate model was constructed using the predictors shown in Table IV. Wound location and treatment modality were both found to be significant predictors, but there was interaction noted between the two variables (P = .006 for the interaction term). Among patients with forefoot wounds, endovascular intervention was associated with higher risk compared to bypass (HR 2.25, P < .001); this was not true in patients with heel wounds (HR 0.67, P = .31). Similarly, among patients undergoing bypass, heel wounds were a risk factor for amputation or death (HR 3.91, P < .001); this was not true among patients undergoing endovascular intervention (HR 1.17, P = .46). Increased age, ESRD, and COPD all predicted poorer outcomes; former smoking and hyperlipidemia were again seen to be protective but DM was not.

Table IV.

Predictors of major amputation or death in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. Stratified HRs are presented for treatment modality and intervention type due to a significant interaction between them. Endo: endovascular intervention. ESRD: end-stage renal disease. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Multivariate Predictor | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endo vs. bypass | 2.25 with forefoot wound | 1.52 – 3.33 | <0.001 |

| 0.67 with heel wound | 0.31 – 1.45 | 0.31 | |

| Heel vs. forefoot wound | 3.91 with bypass | 1.84 – 8.32 | <0.001 |

| 1.17 with endo | 0.78 – 1.76 | 0.46 | |

| Age (per year) | 1.03 | 1.02 – 1.04 | <0.001 |

| ESRD | 2.49 | 1.83 – 3.39 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 1.79 | 1.28 – 2.49 | 0.001 |

| Smoking | |||

| Former | 0.61 | 0.46 – 0.83 | 0.001 |

| Current | 1.05 | 0.69 – 1.61 | 0.82 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.60 | 0.46 – 0.78 | <0.001 |

3.4 Secondary Outcomes

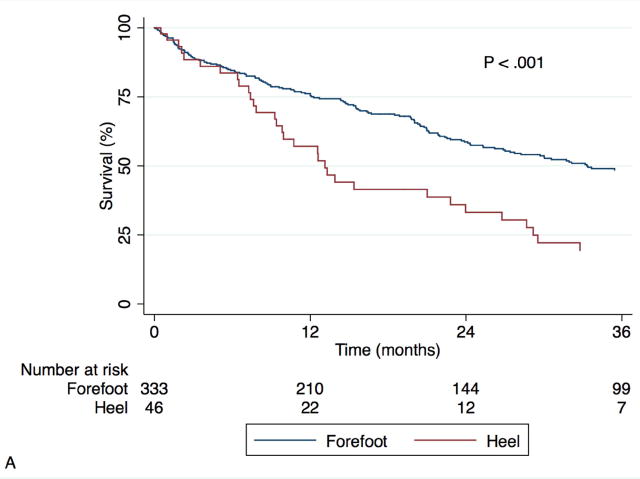

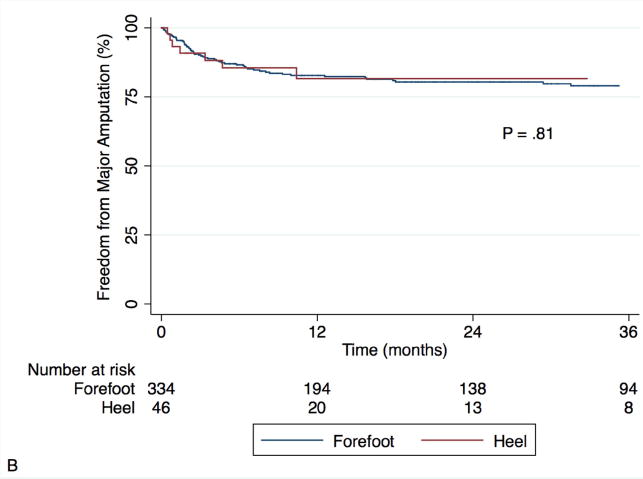

Fig. 2 shows Kaplan-Meier curves for mortality and amputation as individual outcomes. The overall mortality rate in our cohort was 26.4% at one year and 55.3% at three years. Predictors of mortality were found to be the same as those for AFS, with similar univariate hazard ratios. The same multivariate model was constructed with mortality as the outcome of interest and again a strong interaction was observed between wound location and treatment modality (P = .003). Adjusted for the predictors in Table IV, endovascular intervention was associated with greater risk of mortality in those with forefoot wounds (HR 2.62, 95% CI 1.67-4.12, P < .001) but not heel wounds (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.29-1.47, P = .305). Heel wounds were associated with significantly greater mortality after bypass (HR 5.70, 95% CI 2.50-13.03, P < .001) and a trend toward greater mortality after endovascular intervention (HR 1.43, 95% CI 0.94-2.16, P = 0.092). Amputation rates, on the other hand, did not differ by wound location. The overall major amputation rate was 17.8% at one year and 20.8% at three years, with no difference by wound location (P = .81) or treatment modality (P = .33).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for survival (A) and freedom from major amputation (B), stratified by wound location.

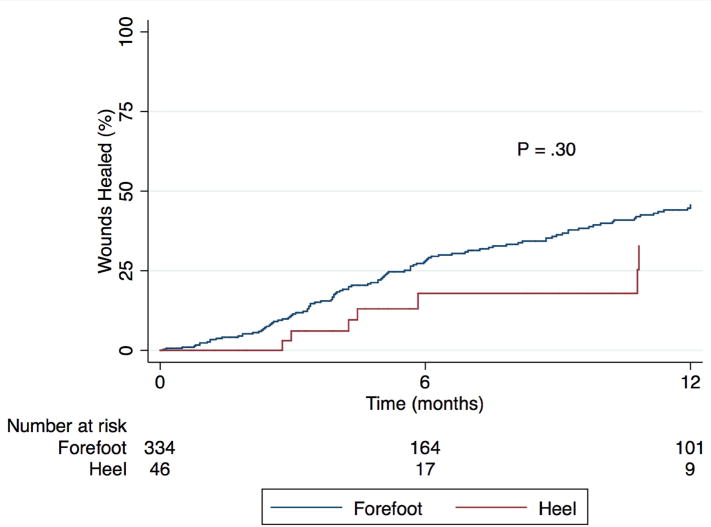

Wound healing rates and patency of bypass or endovascular intervention were similar between groups. Fig. 3 shows Kaplan-Meier curves for complete wound healing, with patients censored if they underwent major amputation. The wound healing rate was 43.1% at one year. There was no difference by wound location (P = .30). Wound healing rates also did not differ by WIfI wound severity (P = .73), or any of the predictors in Table III. Overall primary, primary assisted, and secondary patency were 41.3%, 57.1%, and 73.5% at one year and 32.3%, 50.1%, and 67.3% at three years, respectively. In the overall cohort, endovascular intervention was associated with decreased primary patency (HR 1.76, P = .0005) and primary assisted patency (HR 2.75, P < .0001), and a trend toward decreased secondary patency (HR 1.37, P = .19). There were no differences in patency rates by wound location, though there was a trend toward improved secondary patency in patients with forefoot wounds (P = .64, .97, and .17, respectively).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of complete wound healing, among patients not undergoing major amputation, stratified by wound location.

Outcomes in the 5 patients with evidence of heel osteomyelitis were individually reviewed. Two patients underwent bypasses. The first patient experienced graft occlusion at 4 months, but survived without amputation for 2.5 years. The second patient required amputation at 3.4 months despite a patent bypass and died perioperatively. Three patients underwent endovascular intervention. One was lost to follow-up at 1 month. A second required re-intervention for vessel occlusion at 5.2 months, but survived without amputation for 12.6 months. The final patient required major amputation at 1.4 months and died at 7.4 months.

4. Discussion

Non-healing ischemic foot ulcerations are reflective of severe peripheral arterial disease, and in the absence of revascularization nearly all such wounds necessitate amputation [2]. There has been increasing interest in the impact of wound location on patient outcomes [10]. Heel ulcerations tend to occur in patients with numerous medical comorbidities in the setting of prolonged immobility, and we sought to investigate whether the presence of a heel wound is independently predictive of poorer outcomes.

We conducted this study to determine whether patients with heel wounds are at higher risk for major amputation or death after presenting with infrapopliteal arterial disease. Though there is immense variability in the locations and severity of anatomic disease, we limited our study to patients with significant infrapopliteal disease in order to maximize the consistency within our cohort. We did find a significant difference between groups, but surprisingly this difference was driven entirely by higher rates of post-operative mortality in the heel wound patients. The rates of major amputation, successful wound healing, and patency of revascularization were similar between the two groups. The reason for the isolated difference in mortality is not entirely clear, but it does not appear to be related to the index limb or the revascularization itself. Based on our clinical experience, we postulate that the presence of a heel wound is a marker of poor global health status, and that the cause of death in these patients is often secondary to an unrelated disease process, either cardiovascular or otherwise. There is increasing evidence in the literature that it is possible to identify patients who are “frail” and are at high risk for mortality and other complications following an operation [15]. Though heel wounds are not a component of frailty, in the population of patients with critical limb ischemia a heel wound may predict non-limb related complications following a revascularization procedure in a similar fashion.

We found in our multivariate model that, while heel wounds did affect long-term mortality, this effect was conditional on the treatment received. In particular, we found that surgical bypass predicted improved long-term mortality only in patients with forefoot wounds. We suspect that the mortality difference between treatment modalities reflects selection bias, in that bypass was typically reserved for patients with fewer or less severe baseline comorbidities. However, this effect was not seen in patients with heel wounds. This discrepancy suggests that in the presence of a heel wound, the patient's overall burden of associated medical comorbidities has a far greater impact on mortality risk, and may even preclude the surgeon's ability to select appropriate candidates for surgical bypass. The median survival of patients with heel wounds in our cohort was approximately one year, and those with calcaneal osteomyelitis fared particularly poorly. In the context of such high mortality rates, a lower-risk endovascular intervention may be appropriate even in the face of concerns regarding patency and limb salvage rates in the long-term. Furthermore, such patients should be counseled regarding long-term expectations, and in many cases palliative wound care should be discussed as an appropriate option, with primary amputation performed as needed for overwhelming infection or severe pain. In patients considered poor operative candidates, minor amputation and local wound care, even in the presence of critical limb ischemia, have been shown to mitigate the need for major amputation and preserve functional status [16].

There were several limitations to this study. As a retrospective analysis, there was likely inherent selection bias with respect to treatment offered; we used our multivariate analysis to adjust for these factors to some extent, but we cannot account for other unknown or unmeasured confounders that distinguish certain subgroups of patients. The protective effects of hyperlipidemia and former smoking in our model, for instance, may have been proxies for statin use and positive lifestyle modifications, respectively. In addition, we excluded patients who did not undergo revascularization. It is plausible that these patients had poorer mortality and limb salvage rates than those who were treated. In particular, we noted a relatively low rate of heel osteomyelitis compared to that seen in our clinical practice; those with extensive osteomyelitis were likely offered palliative wound care or a primary amputation rather than a revascularization procedure. More granular wound data was not easily obtainable from the EMR, and we were not able to perform an angiosome-based analysis in this cohort. Likewise, immobility, a risk factor for heel wounds, could not easily be assessed from a retrospective review. Finally, we were not able to adequately assess the quality or intensity of non-operative aspects of treatment such as wound care and nutritional optimization, which are critically important even with successful revascularization. A study involving prospectively-collected data with greater detail on wounds and risk factor modification would be beneficial in addressing many of these limitations.

5. Conclusions

In the setting of infrapopliteal arterial disease, patients presenting with an ischemic heel ulcer are at increased risk of mortality compared to those with a forefoot ulcer. Bypass is associated with improved outcomes in patients with forefoot wounds but not those with heel wounds. Wound healing and major amputation rates were equivalent between groups, as were patency rates. Patients with heel wounds that are deemed appropriate for revascularization may benefit more from endovascular therapy rather than surgical bypass. In the face of such high mortality rates, palliative wound care or primary amputation should be considered more strongly in patients with heel wounds.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number 5T32HL098036-08].

Funding: This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number 5T32HL098036-08].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Reinecke H, Unrath M, Freisinger E, et al. Peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischaemia: still poor outcomes and lack of guideline adherence. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:932–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farber A, Eberhardt RT. The Current State of Critical Limb Ischemia. JAMA Surg. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conte MS. Critical appraisal of surgical revascularization for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:8S–13S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.05.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Q, Shi Y, Wang Y, et al. Patterns of disease distribution of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. Angiology. 2015;66:211–8. doi: 10.1177/0003319714525831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alzamora MT, Forés R, Baena-Díez JM, et al. The peripheral arterial disease study (PERART/ARTPER): prevalence and risk factors in the general population. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. Inter-Society Consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II) International Angiology. 2007;26:82–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Chen J, Mohler ER, et al. Risk Factors for Peripheral Arterial Disease among Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:136–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.02.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills JL, Conte MS, Armstrong DG, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Threatened Limb Classification System: Risk stratification based on Wound, Ischemia, and foot Infection (WIfI) f on behalf of the Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Guidelines. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:220–234.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darling JD, McCallum JC, Soden PA, et al. Predictive ability of the Society for Vascular Surgery Wound, Ischemia, and foot Infection (WIfI) classification system following infrapopliteal endovascular interventions for critical limb ischemia. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2016:616–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.03.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biancari F, Juvonen T. Angiosome-targeted lower limb revascularization for ischemic foot wounds: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;47:517–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chae KJ, Shin JY. Is angiosome-targeted angioplasty effective for limb salvage and wound healing in diabetic foot?: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aerden D, Denecker N, Gallala S, et al. Wound morphology and topography in the diabetic foot: Hurdles in implementing angiosome-guided revascularization. Int J Vasc Med. 2014:2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/672897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang TY, Huang TS, Wang YC, et al. Direct Revascularization With the Angiosome Concept for Lower Limb Ischemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1427. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chipchase SY, Treece KA, Pound N, et al. Heel ulcers don't heal in diabetes. Or do they? Diabet Med. 2005;22:1258–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIsaac DI, Bryson GL, van Walraven C. Association of Frailty and 1-Year Postoperative Mortality Following Major Elective Noncardiac Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5085. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barshes NR, Gold B, Garcia A, et al. Minor amputation and palliative wound care as a strategy to avoid major amputation in patients with foot infections and severe peripheral arterial disease. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2014;13:211–9. doi: 10.1177/1534734614543663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]