Abstract

Varenicline, a partial agonist for α4β2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and a full agonist for α3β4 and α7 nAChRs, is approved for smoking cessation treatment. Although, partial agonism at α4β2* nAChRs is believed to be the mechanism underlying the effects of varenicline on nicotine reward, the contribution of other nicotinic subtypes to varenicline’s effects on nicotine reward is currently unknown. Therefore, we examined the role of α5 and α7 nAChR subunits in the effects of varenicline on nicotine reward using the conditioned place preference (CPP) test in mice. Moreover, the effects of varenicline on nicotine withdrawal-induced hyperalgesia and aversion are unknown. We also examined the reversal of nicotine withdrawal in mouse models of dependence by varenicline.

Varenicline dose-dependently blocked the development and expression of nicotine reward in the CPP test. The blockade of nicotine reward by varenicline (0.1 mg/kg) was preserved in α7 knockout mice but reduced in α5 knockout mice. Administration of varenicline at high dose of 2.5 mg/kg resulted in a place aversion that was dependent on α5 nAChRs but not β2 nAChRs. Furthermore, varenicline (0.1 and 0.5 mg/kg) reversed nicotine withdrawal signs such as hyperalgesia and somatic signs and withdrawal-induced aversion in a dose-related manner.

Our results indicate that the α5 nAChR subunit plays a role in the effects of varenicline on nicotine reward in mice. Moreover, the mediation of α5 nAChRs, but not β2 nAChRs are probably needed for aversive properties of varenicline at high dose. Varenicline was also shown to reduce several nicotine withdrawal signs.

Keywords: varenicline, nicotine, alpha 5 nicotinic receptor, conditioned place preference, withdrawal

1. Introduction

Varenicline (Chantix®) was approved by the FDA for smoking cessation in 2006. Its clinical efficacy and advantage compared to bupropion and nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) is well established (Gonzales et al., 2006; Jorenby et al., 2006). However, all these pharmacotherapies are of limited effectiveness since only about one-fifth of smokers are able to maintain long-term abstinence with any of these drugs (Health and Report, 2008; Schnoll and Lerman, 2006). Therefore, an increased understanding of the mechanisms through which varenicline reduces nicotine dependence could aid in the identification of new treatment targets, and better inform pharmacotherapy of smoking cessation.

In vitro binding and functional studies showed that varenicline is a α4β2* nicotinic receptor (nAChR) partial agonist (Mihalak et al., 2006; Rollema et al., 2007) [* denotes that these nAChRs may contain other α and β subunits as well [Reviewed in (Gotti et al., 2006)]. Partial agonism at α4β2* nAChRs is believed to be the mechanism by which varenicline reduces nicotine reward in the self-administration paradigm (George et al., 2011; O’Connor et al., 2010; Rollema et al., 2007) as well as nicotine-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Reperant et al., 2010) in rodents. However, other subunits such as α5 or α6 can contribute to the α4β2* receptor heteromeric nAChRs and form subtypes such as α4α5β2, which are present in the brain and are expressed on dopaminergic nerve terminals (Zoli et al., 2002). In fact, the agonist activity of varenicline is reduced by α4β2α5 receptors compared to high sensitivity α4β2 nAChR subtypes (Peng et al., 2013). In addition, varenicline has recently been demonstrated to be a full agonist at α7 and α3β4 nAChRs with a higher potency at these two subtypes than nicotine (Grady et al., 2010; Mihalak et al., 2006). However, the contribution of these nicotinic subtypes to varenicline’s effects on nicotine reward is currently unknown. We therefore examined the role of α5 and α7 nAChR subunits in the effects of varenicline on nicotine reward using the conditioned place preference (CPP) test.

An important aspect of varenicline effectiveness as a smoking cessation agent is that it can reduce the severity of nicotine withdrawal (Gonzales et al., 2006; Jorenby et al., 2006; Nakamura et al., 2007). Emerging evidence from human studies indicates that co-occurring pain and pain-related cognitive processes may play a role in the maintenance of tobacco dependence (Ditre et al., 2016, 2011; LaRowe et al., 2017). Animal studies have long established that alterations in nociception and pain sensitivity occur after withdrawal from nicotine (Cohen et al., 2015; Damaj et al., 2003). Although current research in humans has not addressed the effects of varenicline on nicotine withdrawal-associated changes in pain sensitivity, animal models can be used effectively to evaluate such effects. As no studies have reported the effects of varenicline on nicotine withdrawal-induced hyperalgesia, another goal of the present study was to examine the aspects of varenicline that effect nicotine withdrawal and pain reactivity in mouse models of dependence. Additional experiments evaluated whether varenicline would reverse nicotine withdrawal-associated aversion, hyperalgesia, and other somatic signs in the same conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

In the current study, ICR male mice (8 weeks upon arrival; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were used to test the effect of varenicline on nicotine reward and withdrawal, unless noted otherwise. Genetically modified female and male mice (equal sexes in each group) for certain nAChRs were used to investigate possible mechanism in varenicline’s effect. The genetically modified mice (null for the α5, β2 and α7 nAChR subunit and their wild-type littermates) were bred in an animal care facility at Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond, VA) and are maintained on a C57BL/6J background with a backcrossing to at least N12 generations as described previously (Jackson et al., 2009). Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and were used only for backcrossing.

Mice were housed four per cage with ad libitum access to food and water on a 12-h light cycle in a 21 °C humidity- and temperature-controlled room that was approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Experiments were performed during the light cycle and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University and followed the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Drugs

(−)-Nicotine hydrogen tartrate [(−)-1-methyl-2-(3-pyridyl) pyrrolidine (+)-bitartrate] and mecamylamine HCl (non-selective nAChR antagonist) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Varenicline (7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-6,10-methano-6H-pyrazino(2,3-h)(3)benzazepine) was supplied by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA Drug Supply Program, Bethesda, MD). Drugs were dissolved in physiological saline and administered subcutaneously (s.c.) and freshly prepared solutions were given to mice at 10 ml/kg. All doses are expressed as the free base of the drug. All studies were conducted by an experimenter blinded to treatment.

2.3. Conditioned place preference (CPP) studies

An unbiased five-day CPP paradigm was performed, as we previously described (Jackson et al., 2017). A three-chamber design CPP apparatus (ENV3013; Med Associates, St Albans, VT) was used to determine possible place preference or avoidance in testing nicotine and varenicline. On day 1, animals were allowed to freely move in all chambers (two conditioning chambers with a central acclimation chamber) for a 15-min duration and the baseline time spent for each chamber was recorded. A CPP box was consisted of three chambers: two outer chambers (20×20×20 cm each; white mesh & wall or black rod & wall) and a small grey chamber in the middle connected to each outer chamber with a door. White and black chambers were used to condition animals to test drug or vehicle. Based on the time spent in each conditioning chamber, animals were divided into equal group of mice whenever is possible. Mice were confined in differed chambers after vehicle or test drug administration for twenty minutes for a three-day conditioning period (days 2–4). These conditioning sessions were included two sessions as morning and afternoon for each day; animals were confined in one chamber (e.g. white) in the morning and in other chamber (e.g. black) in the afternoon. While control groups received saline in both morning and afternoon sessions, the drug group received nicotine, varenicline, or their combination in one session and saline in other session. Pretreatment times for nicotine and varenicline were as follows: 5 and 10 minutes, respectively. The drug-paired chamber was determined by randomization. Morning and afternoon sessions were 4 hr apart from each other. All sessions were conducted by the same experimenter. On day 5, mice were given access to move freely in all chambers for a 15-min duration without any drug administration. The preference score was found by determining the difference between time spent in the drug paired side on day 5 versus the time in drug paired side on day 1. A significant positive response in time spent in the drug-paired chamber was interpreted as a CPP.

2.4. Nicotine precipitated withdrawal studies

In order to test whether varenicline is able to attenuate nicotine withdrawal, we used a mouse nicotine precipitated withdrawal model as previously described (Damaj et al., 2003). For this reason, mice were implanted with s.c. osmotic minipumps (model 2000; Alzet Corporation, Cupertino, CA) under isoflurane anesthesia and infused with 24 mg/kg/day nicotine or saline for 14 days (Jackson et al., 2008). Nicotine concentration was adjusted according to animal weight and minipump flow rate. On the morning of day 15, mice were pretreated with vehicle, varenicline (0.05, 0.1 and 0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) 10 min before challenge with the non-selective nAChR antagonist, mecamylamine (2 mg/kg, s.c.) to precipitate withdrawal. As described previously (Jackson et al., 2008), we evaluated the occurrence of somatic signs and hyperalgesia nicotine withdrawal signs 10 min after mecamylamine injection. Mice were put in an empty cage and observed for a 20-min period. Paw and body tremors, head shakes, backing, jumps, curls, and ptosis were considered somatic signs. First, the total number of somatic signs was evaluated for each mouse, then, the average number of observed somatic signs was determined for each test group. Hot plate test (Thermojust Apparatus, Richmond, VA) was used to evaluate possible hyperalgesia following the somatic sign assessment. Mice were placed on the hot plate (52°C) and the latency to reaction time (jumping or paw licking) was recorded. The cut-off time was set to 20-s.

2.5. Precipitated nicotine withdrawal measured by the conditioned place avoidance (CPA) test

Further, we sought to test whether varenicline is able to reverse nicotine withdrawal-induced CPA. To establish nicotine CPA, higher doses of nicotine infusion and mecamylamine were used as described previously (Jackson et al., 2008). Therefore, we used this model to investigate the effects of varenicline on nicotine abstinence-related CPA. CPA protocol was conducted using the CPP apparatus, as we previously described (Jackson et al. 2009). Mice were implanted s.c. osmotic minipump to receive a continuous nicotine (36 mg/kg/day) infusion for 28 days (Jackson et al., 2008). After chronic nicotine infusion, these mice underwent a CPA test which conditioning was conducted over the course of four days in a biased fashion. Mice were first tested for their baseline values in CPP apparatus as described above on their first day. Later, animals were paired to mecamylamine or control groups based on their baseline preference scores. The most preferred chamber of each mouse was chosen for mecamylamine paired group. On Days 2 and 3 of CPA conditioning, all mice received saline injections in the morning session and mecamylamine (3.5 mg/kg; s.c.) in the afternoon session. Before mecamylamine administration, mice were pretreated (15 min) with varenicline (0.05 and 0.1 mg/kg, s.c.) or vehicle (s.c.). On the test day (afternoon of day 4), the first day procedure was repeated, and mice were allowed to move freely between chambers. The preference score was found by determining the time spent in the initially preferred chamber at baseline minus the amount of time spent in the initially preferred compartment on test day. A significant negative response in time spent in the mecamylamine-paired chamber was interpreted as a CPA.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Behavioral results were analyzed using the GraphPad software, version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) and expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. Statistical analysis was performed with mixed-factor ANOVA. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine effect of varenicline in CPP test and withdrawal assays. Two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate effect of varenicline on nicotine-induced CPP and aversion at the different doses and in different genotypes. Prior to the ANOVA test, the data were first assessed for the normality of the residuals and homogeneity of variance. Variances were similar between groups and were assessed using either the F-test, the Brown–Forsythe test and the Bartlett’s test for one-way ANOVA or Levene’s test for two-way ANOVA. All data passed these tests. Significant overall ANOVA are followed by Tukey’s post hoc correction when appropriate. All differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Varenicline blocked nicotine CPP

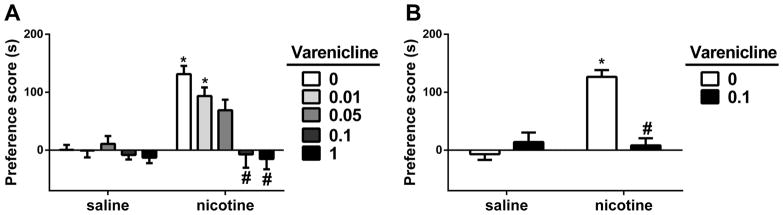

We first evaluated the effect of varenicline pretreatment on the development of nicotine CPP in male ICR mice. For that, animals were pretreated with varenicline prior to nicotine on conditioning days. Two-way ANOVA revealed that significant effects for nicotine treatment [F (1, 7) = 77.23, p < 0.05], varenicline pretreatment [F (4, 28) = 13.16, p < 0.05] and interaction [F (4, 28) = 6.681, p < 0.05]. As revealed by the Tukey’s post hoc, mice conditioned with 0.5 mg/kg s.c. of nicotine itself for three days resulted in a significant preference (p<0.05; Fig. 1A). However, pretreatment with varenicline (0.01, 0.05, 0.1 and 1 mg/kg; s.c.) given 10 min prior to nicotine (0.5 mg/kg; s.c.), inhibited nicotine CPP in a dose dependent manner (p<0.05; Fig. 1A). Varenicline at the doses of 0.1 and 1 mg/kg totally blocked the effect of nicotine in CPP test without inducing significant changes in preferences on their own.

Figure 1. Effects of varenicline on nicotine reward in the conditioned place paradigm.

A) Male ICR mice were conditioned with either subcutaneous (s.c.) saline or nicotine (0.5mg/kg) for 3 days. Saline (s.c.) or varenicline (0.01, 0.05, 0.1, and 1 mg/kg; s.c.) pretreatment were given 10-min prior to nicotine-conditioning. Nicotine itself induced a robust place preference and varenicline pretreatment dose-dependently blocked the effect of nicotine. B) Male ICR mice were conditioned with either s.c. saline or nicotine (0.5mg/kg) for 3 days. Saline (s.c.) or varenicline (0.1 mg/kg; s.c.) were given as a challenge 24 hour after last nicotine-conditioning and 10-min prior to test. Nicotine itself induced a robust place preference and varenicline challenge blocked the effect of nicotine. * Denotes p<0.05 from vehicle control; # Denotes p<0.05 from nicotine control. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of n=8 mice per group.

We then evaluated the effect of acute injection of varenicline on the expression of nicotine CPP. For that, animals were conditioned with nicotine (0.5 mg/kg; s.c.) or saline for three days. Twenty-four hours after last conditioning with either nicotine or saline, mice were given a single injection of varenicline (0.1 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline just 10 min before preference testing. A two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to determine the effect of acute injection of varenicline on nicotine CPP. Significant effects for nicotine treatment [F (1, 28) = 24.69, p < 0.05], varenicline treatment [F (1, 28) = 14.43, p < 0.05] and interaction [F (1, 28) = 29.55, p < 0.05] was found. Varenicline attenuated the expression of nicotine-induced CPP. Nicotine induced a robust CPP (p<0.05; Fig. 1B) and this effect of nicotine was significantly blocked by varenicline (0.1 mg/kg; s.c.), which administered on day five, 10 min prior to test (p<0.05; Fig. 1B).

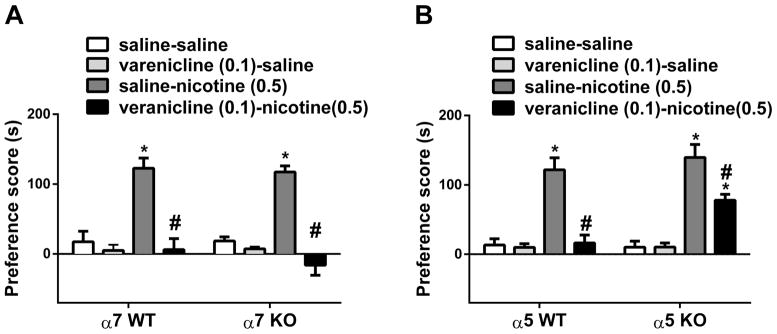

3.2. α5 but not α7 nicotinic subunits play a role in varenicline’s effects on nicotine CPP

In this experiment, we sought to determine which nAChR subtypes mediate the blockade of nicotine CPP by varenicline. While varenicline is a partial α4β2* nAChR agonist, it is also a full agonist on α7 nAChRs (Mihalak et al., 2006). In addition, α5 subunit can contribute to formation of heteromeric α4β2* nAChRs, such as α4α5β2 (Zoli et al., 2002). We therefore, determined the roles of α7 and α5 nicotinic subunits in varenicline’s effect on the development of nicotine CPP. We first examined varenicline blockade of nicotine CPP in α7 knockout mice and their wild type counterparts in the first series of experiments. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant effects for treatment [F (3, 56) = 48.97, p < 0.05], but not for α7 genotype [F (1, 56) = 0.5503, p > 0.05] and interaction [F (3, 56) = 0.4748, p > 0.05]. Tukey’s post hoc showed that nicotine on its own induced a significant CPP (p < 0.05) and varenicline significantly blocked this nicotine CPP in α7 wild type mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 2). Moreover, the blockade of nicotine-induced CPP by varenicline (0.1 mg/kg; s.c.) was preserved in α7 knock out mice (p < 0.05; Fig 2A). In the second series of experiments, we used α5 knockout mice and their wild type counterparts to determine the role of α5 subunits in varenicline’s effect. Two-way ANOVA revealed that significant effects for treatment [F (3, 56) = 47.72, p < 0.05], α5 genotype [F (1, 56) = 5.499, p < 0.05] and interaction [F (3, 56) = 3.311, p < 0.05]. As seen in Fig 2B, the blockade of nicotine-induced CPP by varenicline (0.1 mg/kg; s.c.) was partially lifted in α5 knockout mice (p < 0.05).

Figure 2. Involvement of α7 and α5 nicotinic subunits in the effects of varenicline on nicotine.

Wild type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice for A) α7 and B) α5 nAChRs subunits were conditioned with either subcutaneous (s.c.) saline or nicotine (0.5mg/kg) for 3 days. Saline (s.c.) or varenicline (0.1 mg/kg; s.c.) pretreatment were given 10-min prior to nicotine-conditioning. Nicotine itself induced a robust place preference in α7 and α5 WT mice. Varenicline pretreatment blocked the effect of nicotine in α7 KO mice but not in α5 KO mice. * Denotes p<0.05 from vehicle control; # Denotes p<0.05 from nicotine control. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of n=8 mice per group.

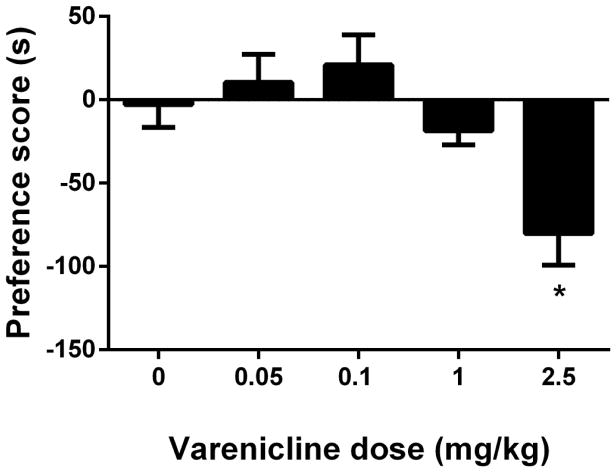

3.3. Varenicline did not induce CPP but it resulted in CPA at the highest dose

While varenicline on its own did not induce a significant change in preference in the CPP test at doses that completely blocked nicotine’s effects (Fig. 1), a non-significant trend toward aversion was observed at the highest dose of 1 mg/kg. We therefore reevaluated varenicline’s effects in the CPP test using a wider dose range (0.05 to 2.5 mg/kg). This range is also in line with several studies where varenicline was used at higher doses than 1 mg/kg in mice (Rodriguez et al., 2014; Gubner et al., 2014; Lange-Asschenfeldt et al., 2016; Slater et al., 2016). For this reason, male ICR mice were conditioned with either saline or varenicline (0.05, 0.1, 1 and 2.5 mg/kg; s.c.) for 3 days with a 10-min pretreatment prior to conditioning in the CPP paradigm. As seen in Figure 3, varenicline induced aversion in a dose-related manner [F (4, 35) = 6.408, p < 0.05] and a robust conditioned place aversion (CPA) was observed in mice at the highest dose (2.5 mg/kg) used in this study (p < 0.05; Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Effects of varenicline in the conditioned place paradigm.

Male ICR mice were conditioned with either subcutaneous (s.c.) saline or varenicline (0.05, 0.1, 1 and 2.5 mg/kg; s.c.) for 3 days with a 10-min pretreatment prior to conditioning. A robust aversion was observed in varenicline-conditioned mice. * Denotes p < 0.05 from saline. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of n=8 mice per group.

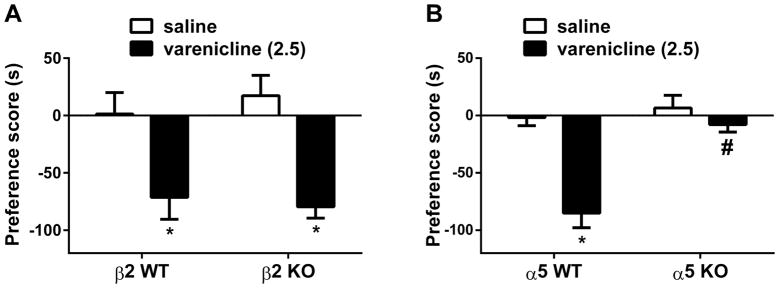

Since α5, but not α7, nAChR subunits were shown to be involved in the effect of varenicline on nicotine CPP (Figure 2), we assessed their role in varenicline-induced place aversion. We also examined the role of β2* nAChR subunit in this effect since varenicline is a partial agonist at β2* nAChR. A separate group of and β2 and α5 knockout mice and their wild type littermates were exposed to a three-day conditioning of varenicline (2.5 mg/kg, s.c.). As seen in Figure 4, varenicline-induced CPA did not differ between β2 knockout mice and wild type mice [Two-way ANOVA revealed no significant effects for genotype: F (1, 50) = 0.054, p > 0.05]. In contrast, varenicline-induced CPA disappeared completely in α5 knockout mice. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant effects for treatment [F (1, 28) = 25.53, p < 0.05], α5 genotype [F (1, 28) = 19.64, p < 0.05] and interaction [F (1, 28) = 12.68, p < 0.05]. As revealed by the Tukey’s post hoc, varenicline significantly induced an aversion in wild type mice (p<0.05), but it was ineffective in knockout mice (p > 0.05; Fig 4).

Figure 4. Involvement of β2 and α5 nicotinic subunits in varenicline-induced conditioned place aversion.

Wild type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice for A) β2 and B) α5 nAChRs subunits were conditioned with either subcutaneous (s.c.) saline or varenicline (2.5 mg/kg) for 3 days. Varenicline induced a significant place aversion in β2 and α5 WT mice. However, the CPA developed in in β2 KO mice but not in α5 KO mice. *Denotes p<0.05 from vehicle control; # Denotes p<0.05 from varenicline WT. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of n=8 mice per group.

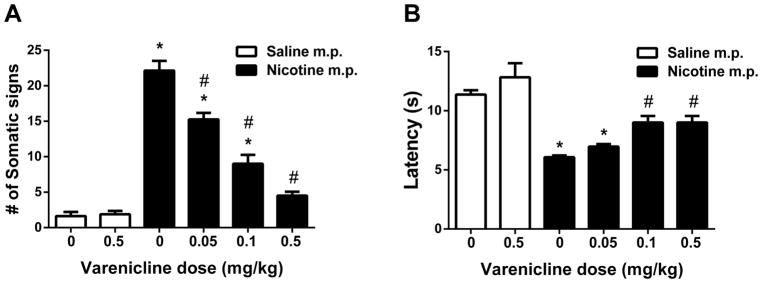

3.4. Nicotine withdrawal and hyperalgesia signs attenuated by varenicline

The somatic signs and hyperalgesia signs of nicotine withdrawal were determined in male ICR mice which infused 24 mg/kg/day via minipumps for 14 days. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms were assessed following pretreatment with either varenicline or saline 10 min prior to mecamylamine administration on day 15. One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test revealed that significant differences due to treatments were found in all parameters that measured as somatic signs [F (5, 42) = 76.67, p < 0.05; Fig. 5A] and hyperalgesia [F (5, 42) = 17.69, p < 0.05; Fig. 5B]. Tukey’s post hoc showed that nicotine withdrawal was observed as a significant increased expression of somatic withdrawal signs (p < 0.05; Fig. 5A), and decreased response latencies in the hot-plate test (p < 0.05; Fig. 5B) compared to control mice implanted with saline minipumps. While the highest dose of varenicline tested (0.5 mg/kg) did not significantly alter any behavioral responses in saline-infused mice in any withdrawal test, it affected withdrawal signs in nicotine infused mice. Indeed, varenicline pretreatment (0.05, 0.1 and 0.5 mg/kg; s.c.) decreased nicotinic somatic withdrawal signs at all doses (p < 0.05). Varenicline also totally blocked somatic signs at the dose of 0.5 mg/kg (Fig. 5A). Pretreatment with varenicline also attenuated the expression of hyperalgesia at 0.1 and 0.5 mg/kg doses (Fig. 5B) (p < 0.05).

Figure 5. Effects of varenicline on physical and affective signs of precipitated nicotine withdrawal.

Male ICR mice were chronically infused with saline or nicotine (24 mg/kg/day) for 14 days. On day 15, mice received subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of saline or varenicline (0.05, 0.1, and 0.5 mg/kg). Mice then were administered mecamylamine (2 mg/kg; s.c.) 10 min prior to behavioral assessment of A) somatic signs, and B) hyperalgesia (hot plate latency). Nicotine induced withdrawal symptoms: increased somatic signs, but decreased hot plate latency. Varenicline pretreatment attenuated somatic signs, and increased hot plate latency in nicotine withdrawn mice in a dose-related fashion. * Denotes p< 0.05 vs. Saline minipump group, # Denotes p< 0.05 vs. Nicotine minipump group. Each point represents the mean ± S.E.M. of n=8 mice per group. MP: minipump

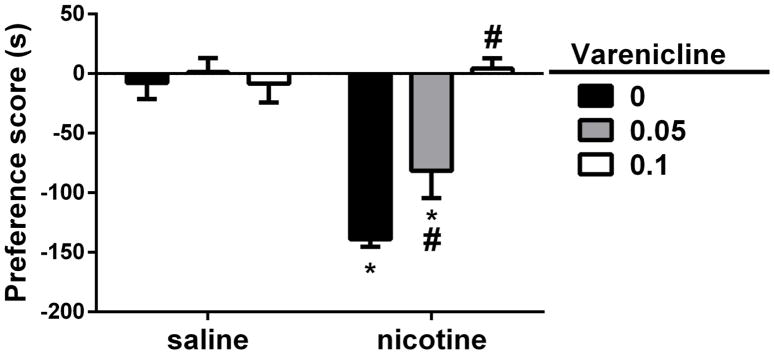

3.5. Varenicline reversed nicotine withdrawal-induced CPA

To investigate the effect of varenicline on nicotine withdrawal-induced CPA, male ICR mice were exposed to a three-day conditioning by nicotine (24 mg/kg; s.c.) and varenicline (0.05 and 0.1 mg/kg; s.c.) was injected 10 min prior to nicotine treatment. On test day, animals were injected a single dose of mecamylamine (3.5 mg/kg; s.c.) to challenge nicotine withdrawal. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test revealed significant effects for nicotine treatment [F (1, 6) = 50.89, p < 0.05], varenicline pretreatment [F (2, 12) = 9.759, p < 0.05] and interaction [F (2, 12) = 13.13, p < 0.05]. Mecamylamine challenge induced an aversive behavior in nicotine-conditioned mice (p<0.05; Fig. 5). On the other hand, varenicline pretreatment before nicotine conditioning reversed the effect of mecamylamine on test day (p<0.05; Fig. 6)

Figure 6. Varenicline reversed mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine withdrawal conditioned placed aversion.

Male ICR mice were chronically infused with saline or nicotine (36 mg/kg/day) for 28 days. On CPA conditioning days, all mice received saline injections in the morning session and mecamylamine (3.5 mg/kg; s.c.) in the afternoon session. 15 min before mecamylamine administration, mice were pretreated with varenicline (0.05 and 0.1 mg/kg, s.c.) or vehicle (s.c.). Varenicline reversed mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine withdrawal CPA. Mecamylamine (3.5 mg/kg, s.c.) precipitated a significant CPA in chronic nicotine-treated mice. However, varenicline pretreatment reversed mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine aversion in a dose-related manner. Each point represents the mean ± S.E.M. of n = 8 mice per group. * denotes p < 0.05 vs. saline group/vehicle; # denotes p < 0.05 from nicotine/vehicle

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that varenicline blocks nicotine rewarding properties in the CPP test in mice. Specifically, α5 but not α7 nicotinic subunits seem to play an important role in varenicline blockade of nicotine-induced preference in mice. In addition, higher doses of varenicline induced an α5 nAChRs-dependent place aversion in mice. Finally, varenicline ameliorates nicotine withdrawal-induced aversion, somatic signs and hyperalgesia in nicotine-dependent mice.

Our results of blockade of nicotine CPP by varenicline in mice are consistent with a previous study showing that varenicline is able to also block nicotine-induced CPP in rats (Biala et al., 2010). The mechanisms underlying varenicline’s blockade of nicotine reward and reinforcement are thought to mainly engage neuronal α4β2 nAChRs. Varenicline is a partial agonist for α4β2 nAChRs (Mihalak et al., 2006), β2*-nAChRs were reported to be crucial for nicotine self-administration (Picciotto et al., 1998) and nicotine CPP does not occur in β2 knockout mice (Walters et al., 2006). Thus, it seems likely that varenicline blocks nicotine preference in our studies through its action on the α4β2* nAChR. However, heteromeric α4β2* nAChRs exist in multiple subtypes such as the α4α5β2. Importantly, mice null for the α5 nAChR subunit showed an enhancement of nicotine intake and CPP (Fowler et al., 2011; Jackson et al., 2010). In addition, D398N (Asp398Asn) polymorphism in the human CHRNA5 gene is associated with nicotine dependence (Bierut et al., 2006; Saccone et al., 2007).

In this study, our results show that the blockade of nicotine CPP by varenicline is partially mediated by the α5 subunit. Thus, accessory α4α5β2 nAChRs may play a role in the effect of varenicline on nicotine’s rewarding properties. Even though varenicline was reported to be a full α7 nAChRs agonist (Mihalak et al., 2006), our results suggest that it does not act on the α7 nAChR to block nicotine reward in the CPP test.

Our study is also the first to show the induction of conditioned aversion by varenicline in the mouse. The effects are similar to those described for nicotine and occurs at higher doses of the drug (Grieder et al., 2017; Pastor et al., 2011; Risinger and Oakes, 1995). However, contrary to nicotine, no CPP was observed for varenicline at lower doses in our study. This is probably due to the low efficacy of varenicline at the α4β2* nAChR subtype. In addition, our data showed that a high dose of varenicline-induced a place aversion which is α5- but not β2-nAChRs mediated. One obvious nAChR candidate is the α3α5β4 subtype where varenicline was shown to be a partial agonist (Rollema et al., 2014; Stokes and Papke, 2012). The mediation of varenicline-induced place aversion by α5 nicotinic subunits is similar to those reported for nicotine. Preclinical published data indicate an important role of α5-containing nAChRs in the regulation of nicotine pharmacological effects (Bagdas et al., 2015; Jackson et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2002). The α4α5β2 nAChRs have been shown to be involved in nicotine-stimulated dopamine release in the striatum (Salminen et al., 2004). More recent data suggest that α5 nicotinic subunits play a role in nicotine aversion in terms of nicotine withdrawal and nicotine intake (Antolin-Fontes et al., 2015; Fowler et al., 2011; Frahm et al., 2011; Grieder et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2008; Salas et al., 2009). Genetically modified Tabac mice, a transgenic mouse model for the CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 gene cluster and overexpressing the β4 nAChR subunit, have been reported to increase sensitivity to nicotine-induced aversion (Frahm et al., 2011). Consistent with this report, the aversive effects of nicotine has been found to be decreased in α5 KO mice in conditioned taste avoidance and CPA tests (Grieder et al., 2017). The present finding would suggest that varenicline use could possibly lead at high doses to a dysphoric and aversive state. While some reports and case studies indicated that varenicline intake may increase neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depressed mood, agitation, and suicidal ideation (Laine et al., 2009; May and Rose, 2010; Moore et al., 2011), later randomized controlled trials revealed no evidence that varenicline is associated with adverse neuropsychiatric side effects (Gibbons and Mann, 2013). It is possible also that the place aversion observed in our animal studies could relate to the high incidence of nausea reported in patients receiving varenicline (Gonzales et al., 2006; Jorenby et al., 2006; Oncken et al., 2006). Indeed, the most common adverse drug reaction reported by people taking varenicline is nausea and its occurrence is dose-related. However, the sites and mechanisms of varenicline conditioned aversion are unknown.

Present study demonstrates that varenicline ameliorates nicotine withdrawal-induced deficits in somatic signs, aversion, and hyperalgesia in mice. The decrease in nicotine withdrawal-induced CPA is similar to the decrease in aversion by varenicline in nicotine-dependent rats using the intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) procedure (Igari et al., 2014). These findings are consistent with studies showing that varenicline is effective in ameliorating the nicotine-withdrawal associated negative affect reported in human smokers (Patterson et al., 2009; West et al., 2008). Human experimental studies have also shown that overnight nicotine deprivation can induce hyperalgesia (Ditre et al., under review), and that pain can be a potent motivator of cigarette smoking (Ditre et al., 2010; Ditre and Brandon, 2008). Given that pain and tobacco addiction frequently co-occur in the general population (Zvolensky et al., 2009), and that nicotine deprivation-induced exacerbation of pain may precipitate relapse to smoking, future research should examine the utility of varenicline in mitigating hyperalgesia during the early stages of a quit attempt.

5. Conclusions

In summary, varenicline was able to block nicotine rewarding properties and attenuate nicotine withdrawal. In addition, we provide evidence that α5 but not α7 nAChR subunits mediate the effects of varenicline on nicotine reward. Moreover, varenicline attenuated nicotine withdrawal-induced deficits. Our results suggest that α5-containing nAChR subtypes may be targeted for improved medications for smoking cessation.

Highlights.

Varenicline (Chantix®) is an approved drug for smoking cessation

α5 nAChRs, but not α7, play a role in the effect of varenicline on nicotine reward

α5 nAChRs, but not β2, mediate the aversive properties of varenicline

Varenicline reduced several nicotine withdrawal signs including hyperlagesia

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants [DA 005274 and DA032246] to MID. Dr. Bagdas’ effort was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P50DA036105 and the Center for Tobacco Products of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- CPP

conditioned place preference

- CPA

conditioned place aversion

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None of the other authors declared a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antolin-Fontes B, Ables JL, Görlich A, Ibañez-Tallon I. The habenulo-interpeduncular pathway in nicotine aversion and withdrawal. Neuropharmacology. 2015;96:213–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdas D, AlSharari SD, Freitas K, Tracy M, Damaj MI. The role of alpha5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mouse models of chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;97:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biala G, Staniak N, Budzynska B. Effects of varenicline and mecamylamine on the acquisition, expression, and reinstatement of nicotine-conditioned place preference by drug priming in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;381:361–370. doi: 10.1007/s00210-010-0498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Madden PAF, Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hatsukami D, Pomerleau OF, Swan GE, Rutter J, Bertelsen S, Fox L, Fugman D, Goate AM, Hinrichs AL, Konvicka K, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Saccone NL, Saccone SF, Wang JC, Chase GA, Rice JP, Ballinger DG. Novel genes identified in a high-density genome wide association study for nicotine dependence. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;16:24–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A, Treweek J, Edwards S, Leão RM, Schulteis G, Koob GF, George O. Extended access to nicotine leads to a CRF 1 receptor dependent increase in anxiety-like behavior and hyperalgesia in rats. Addict Biol. 2015;20:56–68. doi: 10.1111/adb.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj MI, Kao W, Martin BR. Characterization of Spontaneous and Precipitated Nicotine Withdrawal in the Mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:526–534. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Brandon TH. Pain as a Motivator of Smoking: Effects of Pain Induction on Smoking Urge and Behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:467–472. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Brandon TH, Zale EL, Meagher MM. Pain, Nicotine, and Smoking: Research Findings and Mechanistic Considerations. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:1065–1093. doi: 10.1037/a0025544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Heckman BW, Butts EA, Brandon TH. Effects of expectancies and coping on pain-induced motivation to smoke. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:524–533. doi: 10.1037/a0019568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Kosiba JD, Zale EL, Zvolensky MJ, Maisto SA. Chronic Pain Status, Nicotine Withdrawal, and Expectancies for Smoking Cessation Among Lighter Smokers. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9769-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CD, Lu Q, Johnson PM, Marks MJ, Kenny PJ. Habenular α5 nicotinic receptor subunit signalling controls nicotine intake. Nature. 2011;471:597–601. doi: 10.1038/nature09797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frahm S, Œlimak MA, Ferrarese L, Santos-Torres J, Antolin-Fontes B, Auer S, Filkin S, Pons S, Fontaine JF, Tsetlin V, Maskos U, Ibañez-Tallon I. Aversion to Nicotine Is Regulated by the Balanced Activity of β4 and α5 Nicotinic Receptor Subunits in the Medial Habenula. Neuron. 2011;70:522–535. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George O, Lloyd A, Carroll FI, Damaj MI, Koob GF. Varenicline blocks nicotine intake in rats with extended access to nicotine self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213:715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Mann JJ. Varenicline, smoking cessation, and neuropsychiatric adverse events. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1460–1467. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, Watsky EJ, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR VP3S Group. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006;296:47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Zoli M, Clementi F. Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: native subtypes and their relevance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Drenan RM, Breining SR, Yohannes D, Wageman CR, Fedorov NB, McKinney S, Whiteaker P, Bencherif M, Lester HA, Marks MJ. Structural differences determine the relative selectivity of nicotinic compounds for native α4β2*-, α6β2*-, α3β4*- and α7-nicotine acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:1054–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieder TE, George O, Yee M, Bergamini MA, Chwalek M, Maal-Bared G, Vargas-Perez H, van der Kooy D. Deletion of α5 nicotine receptor subunits abolishes nicotinic aversive motivational effects in a manner that phenocopies dopamine receptor antagonism. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;46:1673–1681. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health AUSP, Report S. A Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. A U.S Public Health Service Report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:158–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igari M, Alexander JC, Ji Y, Qi X, Papke RL, Bruijnzeel AW. Varenicline and cytisine diminish the dysphoric-like state associated with spontaneous nicotine withdrawal in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:455–465. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Bagdas D, Muldoon PP, Lichtman AH, Carroll FI, Greenwald M, Miles MF, Damaj MI. In vivo interactions between α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and nuclear peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α: Implication for nicotine dependence. Neuropharmacology. 2017;118:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KJ, Marks MJ, Vann RE, Chen X, Gamage TF, Warner JA, Damaj MI. Role of alpha5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in pharmacological and behavioral effects of nicotine in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:137–46. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.165738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KJ, Martin BR, Changeux JP, Damaj MI. Differential role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in physical and affective nicotine withdrawal signs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:302–12. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KJ, Walters CL, Damaj MI. 2 Subunit-Containing Nicotinic Receptors Mediate Acute Nicotine-Induced Activation of Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II-Dependent Pathways in Vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:541–549. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.153171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti Na, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006;296:56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine P, Marttila J, Lindeman S. Hallucinations in the context of varenicline withdrawal. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:619–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08091370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRowe LR, Zvolensky MJ, Langdon KJ, Zale EL, Ditre JW. Pain-related anxiety as a predictor of early lapse and relapse to cigarette smoking. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;25:255–264. doi: 10.1037/pha0000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May AC, Rose D. Varenicline withdrawal-induced delirium with psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:720–1. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. Varenicline Is a Partial Agonist at α4β2 and a Full Agonist at α7 Neuronal Nicotinic Receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:801–805. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025130.therapies. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TJ, Furberg CD, Glenmullen J, Maltsberger JT, Singh S. Suicidal behavior and depression in smoking cessation treatments. PLoS One. 2011;6:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Oshima A, Fujimoto Y, Maruyama N, Ishibashi T, Reeves KR. Efficacy and Tolerability of Varenicline , an α 4 β 2 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Partial Agonist , in a 12-Week , with 40-Week Follow-Up for Smoking Cessation in Japanese Smokers. Clin Ther. 2007;29:1040–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor EC, Parker D, Rollema H, Mead AN. The α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine-receptor partial agonist varenicline inhibits both nicotine self-administration following repeated dosing and reinstatement of nicotine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;208:365–376. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncken C, Gonzales D, Nides M, Rennard S, Watsky E, Billing CB, Anziano R, Reeves K. Efficacy and safety of the novel selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, varenicline, for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1571–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor V, Host L, Zwiller J, Bernabeu R. Histone deacetylase inhibition decreases preference without affecting aversion for nicotine. J Neurochem. 2011;116:636–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson F, Jepson C, Strasser AA, Loughead J, Perkins KA, Gur RC, Frey JM, Siegel S, Lerman C. Varenicline Improves Mood and Cognition During Smoking Abstinence. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C, Stokes C, Mineur YS, Picciotto MR, Tian C, Eibl C, Tomassoli I, Guendisch D, Papke RL. Differential modulation of brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptor function by cytisine, varenicline, and two novel bispidine compounds: emergent properties of a hybrid molecule. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;347:424–437. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.206904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Rimondini R, Léna C, Marubio LM, Pich EM, Fuxe K, Changeux JP. Acetylcholine receptors containing the β2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature. 1998;391:173–177. doi: 10.1038/34413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reperant C, Pons S, Dufour E, Rollema H, Gardier AM, Maskos U. Effect of the α4β2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline on dopamine release in β2 knock-out mice with selective re-expression of the β2 subunit in the ventral tegmental area. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:346–350. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger FO, Oakes RA. Nicotine-induced conditioned place preference and conditioned place aversion in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;51:457–461. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00007-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, Glowa J, Hurst RS, Lebel LA, Lu Y, Mansbach RS, Mather RJ, Rovetti CC, Sands SB, Schaeffer E, Schulz DW, Tingley FD, Williams KE. Pharmacological profile of the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:985–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Russ C, Lee TC, Hurst RS, Bertrand D. Functional interactions of varenicline and nicotine with nAChR subtypes implicated in cardiovascular control. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:733–742. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone SF, Hinrichs AL, Saccone NL, Chase GA, Konvicka K, Madden PAF, Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hatsukami D, Pomerleau O, Swan GE, Goate AM, Rutter J, Bertelsen S, Fox L, Fugman D, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Wang JC, Ballinger DG, Rice JP, Bierut LJ. Cholinergic nicotinic receptor genes implicated in a nicotine dependence association study targeting 348 candidate genes with 3713 SNPs. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:36–49. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Sturm R, Boulter J, De Biasi M. Nicotinic Receptors in the Habenulo-Interpeduncular System Are Necessary for Nicotine Withdrawal in Mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3014–3018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4934-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Murphy KL, McIntosh JM, Drago J, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Grady SR. Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1526–35. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoll RA, Lerman C. Current and emerging pharmacotherapies for treating tobacco dependence. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2006;11:429–444. doi: 10.1517/14728214.11.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes C, Papke RL. Use of an α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit concatamer to characterize ganglionic receptor subtypes with specific subunit composition reveals species-specific pharmacologic properties. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:538–546. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters CL, Brown S, Changeux JP, Martin B, Damaj MI. The β2 but not α7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is required for nicotine-conditioned place preference in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:339–344. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Orr-Urtreger A, Chapman J, Rabinowitz R, Nachman R, Korczyn AD. Autonomic function in mice lacking α5 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. J Physiol. 2002;542:347–354. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Baker CL, Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG. Effect of varenicline and bupropion SR on craving, nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and rewarding effects of smoking during a quit attempt. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:371–377. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Moretti M, Zanardi A, Mcintosh JM, Clementi F, Gotti C. Identification of the Nicotinic Receptor Subtypes Expressed on Dopaminergic Terminals in the Rat Striatum. 2002;22:8785–8789. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08785.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, McMillan K, Gonzalez A, Asmundson GJG. Chronic pain and cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence among a representative sample of adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:1407–1414. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]