Abstract

Introduction

Studies of neighborhood food environments typically focus on select stores (especially supermarkets) and/or restaurants (especially fast-food outlets), make presumptions about healthfulness without assessing actual items for sale, and ignore other kinds of businesses offering foods/drinks. The current study assessed availability of select healthful and less-healthful foods/drinks from all storefront businesses in an urban environment and considered implications for food-environment research and community health.

Methods

Cross-sectional assessment in 2013 of all storefront businesses (n=852) on all street segments (n=1,253) in 32 census tracts of the Bronx, New York. Investigators assessed for healthful items (produce, whole grains, nuts, water, milk) and less-healthful items (refined sweets, salty/fatty fare, sugar-added drinks, and alcohol), noting whether items were from food businesses (e.g., supermarkets and restaurants) or other storefront businesses (OSB, e.g., barber shops, gyms, hardware stores, laundromats). Data were analyzed in 2017.

Results

Half of all businesses offered food/drink items. More than one seventh of all street segments (more than one third in higher-poverty census tracts) had businesses selling food/drink. OSB accounted for almost one third of all businesses offering food/drink items (about one quarter of businesses offering any healthful items and more than two thirds of businesses offering only less-healthful options).

Conclusions

Food environments include many businesses not primarily focused on selling foods/drinks. Studies that do not consider OSB may miss important food/drink sources, be incomplete and inaccurate, and potentially misguide interventions. OSB hold promise for improving food environments and community health by offering healthful items; some already do.

INTRODUCTION

Studies of neighborhood food environments overwhelmingly have focused on food stores (especially supermarkets) and restaurants (especially fast-food outlets).1–3 Receiving less attention have been other kinds of businesses, yet the availability of food/drink items from other storefront businesses (OSB) may be substantial.

For example, some studies have considered gas marts, pharmacies, and dollar stores to demonstrate the frequent offering of foods/drinks.4–8 At least one study additionally focused on less-intuitive food/drink sources like hardware stores, automobile shops, furniture stores, and apparel outlets, and likewise demonstrated that food/drink offerings are common.9 Other work has examined food/drink availability at check-out counters in a variety of storefront retail.10–12 Taken together, these studies suggest pervasive availability, especially of less-healthful energy-dense convenience items (e.g., candy, cookies, chips, and soda).

The availability of more-healthful items is somewhat less clear. Although some research has considered a range of food/drink offerings through local retail, including healthful items like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and milk,6,8,10 few studies have focused specifically on healthful fare.4,5,7 It is common for research only to focus on less-healthful offerings9,12 or only to focus on very select storefronts.4–8,10

Nonetheless, it is apparent that the availability of healthful items extends beyond just food stores and restaurants.4–8,10 As such, studies that do not include a range of possible sources of healthful and less-healthful foods/drinks may be incomplete and lead to inaccurate conclusions and misguided interventions. For instance, if healthful items are widely available, selectively ignoring certain sources may result in incorrect determinations of food deserts (neighborhoods without access to healthful food) and in misdirected efforts to address gaps that do not exist. Likewise, if less-healthful items are more ubiquitous than generally appreciated,6,8–10,12 selective strategies to restrict availability might miss the most important sources to target. The whole problem of food swamps (areas in which less-healthful-food sources exceed healthier options)13,14 might be understated and go unaddressed.

The current study assesses the availability of healthful and less-healthful foods/drinks from a full range of storefront businesses. Investigators conducted assessment in a diverse urban—setting with widely varying retail density and in sociodemographically dissimilar communities—and considered implications for food environment research and community health.

METHODS

Study Sample

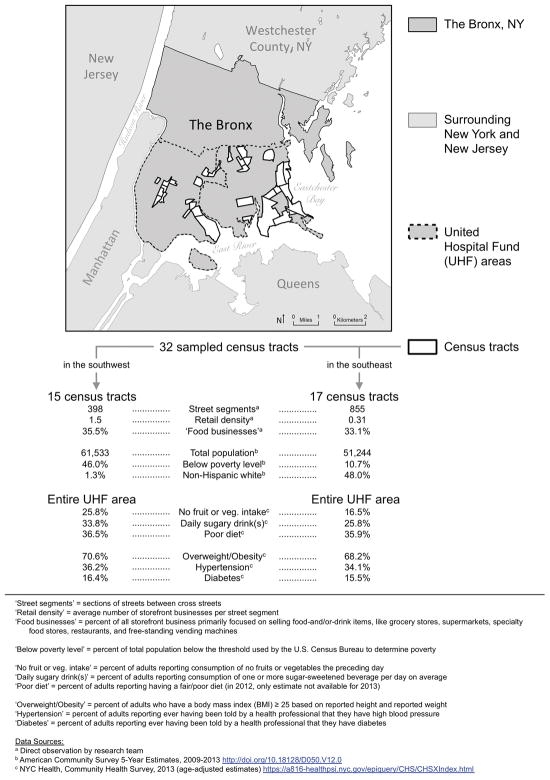

The current study focused within two large geographic areas in the Bronx, New York (Figure 1)—United Hospital Fund areas, used by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene for analytic purposes.15 The two areas differed substantially in sociodemographics (based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey16) and in eating behaviors and rates of diet-related diseases (based on New York City’s Community Health Survey17). The areas were chosen for a broader study to assess neighborhood-level differences in food environments. For that study, investigators selected census tracts having the highest proportions of residents below the Federal poverty level18 (n=15, all in southwest United Hospital Fund area) and the census tracts having the lowest proportions of residents below the Federal poverty level (n=17; all in the southeast United Hospital Fund area) to ensure large differences. It was presumed that differences in poverty rates would correlate with differences in neighborhood environments and that choosing census tracts at the extremes of residential poverty would result in marked variation in both street and retail density. It was also assumed that that there would be marked variation in demographics, diet, and disease rates among individuals living in the census-tract communities.

Figure 1.

Map of the Bronx and the 32 census tracts containing the 1,253 sampled street segments.

For the current study, the 32 selected census tracts were considered together as a single diverse environment (Figure 1). All public streets within these census tracts became the sample for assessment.

Measures

Three trained investigators conducted assessments on all 1,253 street segments (sections of a street between cross streets) in the 32 selected census tracts. Assessments proceeded by walking the length of each side of each street segment to identify any storefront businesses (including free-standing vending machines). All assessments occurred during regular business hours (generally 10:00AM–4:00PM), June–August 2013.

For each identified business, investigators recorded the name, location, type of business, and whether any foods/drinks were offered. Investigators used signage, window displays, menus/menu boards, product displays, and inquiries of staff to determine whether any foods/drinks were for sale and if so, what types.

Details on food/drink categories and examples appear in Table 1. Categories were developed through prior work in food environment assessment.19–23

Table 1.

Food/drink Categories and Healthfulness, With Example Items and Items That Were Not Examples

| Category (healthfulness) |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Foods | ||

| Fruits and vegetables (healthful) |

|

|

| Whole grains (healthful) |

|

|

| Nuts (healthful) |

|

|

| Refined sweets (less healthful) |

|

|

| Salty/Fatty fare (less healthful) |

|

|

| Drinks | ||

| Water (healthful) |

|

|

| Milk (healthful) |

|

|

| 100% juice (neither healthful nor less healthful) |

|

|

| Diet drinks (neither healthful nor less-healthful) Sugar-added drinks (less healthful) |

|

|

| Alcohol (less healthful) |

|

|

Of interest was the presence (yes/no) of any of the following food categories: fruits and vegetables, whole grains, nuts, refined sweets, and salty/fatty fare. Drink categories included: water, milk, 100% juice, diet drinks, sugar-added drinks, and alcohol. When grain-based foods were offered and the availability of whole-grain items not apparent, investigators asked specifically about possible whole-grain options. Likewise, if sugary drinks were available and the availability of healthful drinks not apparent, investigators asked specifically about healthful-drink options.

Consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans,24 the healthful food categories were fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and nuts. The healthful drink categories were water and milk. Less-healthful food categories were refined sweets and salty/fatty fare. Less-healthful drink categories were sugar-added drinks and alcohol. Given current scientific debate about 100% juice25,26 and diet drinks,27 these beverages were considered neither healthful nor less-healthful.

For data collection and management, the study used a secure, web-based application: Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), version 4.5.1. REDCap provides an intuitive interface for validated data entry, audit trails for tracking data manipulation, and automated export procedures for downloads to statistical packages.28

The principal investigator, having conducted earlier food-environment assessments,19–22 including studies using REDCap,23,29 trained other members of the research team in data collection procedures. Three team members practiced procedures by observing 20 storefront businesses outside of the study area—first independently, then as a group.

For independent assessments, there was near-perfect agreement with regard to business name, business location, business type, and food/drink offerings for the 20 selected storefronts (agreement 98.7%). Substantive errors were due to missed items (e.g., one investigator missing a vending machine full of less-healthful snacks at the back of a hair salon).

For the group assessment, no items were missed. There was essentially perfect agreement between the group-collected data and data collected by the principal investigator as the standard for comparison. The only differences were in the examples investigators chose to record for available foods/drinks (e.g., the group noting “whole-wheat bagel” and the principal investigator noting “oatmeal” for whole-grain item available at a donut shop).

Statistical Analysis

In assessing the different types of foods/drinks offered, investigators used two different units of analysis: (1) street segments and (2) businesses. For businesses, analyses additionally distinguished between food businesses (i.e., outlets primarily focused on selling food/drink items, like grocery stores, supermarkets, specialty food stores, restaurants, and free-standing vending machines) and OSB (i.e., all other storefront retail).

Investigators used Stata, version 12.1 for frequency distributions and percentages. Data were analyzed in 2017.

RESULTS

Table 2 shows food/drink offerings in the Bronx by street segment and by storefront businesses. Numbers and percentages described below come from Table 2, or from calculations based on table values unless otherwise noted.

Table 2.

Overall Food/Drink Offerings in the Bronx by Street Segments and by Storefront Businesses

| Sample characteristic | Street segments n (%) | All storefront businesses n (%) | Food businessesa n (%) | OSBb n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totals/denominators | 1,253 (100.0) | 852 (100.0) | 296 (100.0) | 556 (100.0) |

| Offering any food/drink | 184 (14.7) | 432 (50.7) | 296 (100.0) | 136 (24.5) |

| Offering only less healthful items | 4 (0.3) | 79 (9.3) | 23 (7.8) | 56 (10.1) |

| Offering any food | 173 (13.8) | 386 (45.3) | 273 (92.2) | 113 (20.3) |

| Offering any fruits or vegetables | 144 (11.5) | 274 (32.2) | 253 (85.5) | 21 (3.8) |

| Offering any whole grains | 130 (10.4) | 206 (24.2) | 181 (61.1) | 25 (4.5) |

| Offering any nuts | 135 (10.8) | 225 (26.4) | 182 (61.5) | 43 (7.7) |

| Offering any refined sweets | 165 (13.2) | 362 (42.5) | 251 (84.8) | 111 (20.0) |

| Offering any salty/fatty fare | 156 (12.5) | 303 (35.6) | 261 (88.2) | 42 (7.6) |

| Offering only less-healthful foodsc | 6 (0.5) | 79 (9.3) | 13 (4.4) | 66 (11.9) |

| Offering any drink | 172 (13.7) | 368 (43.2) | 287 (97.0) | 81 (14.6) |

| Offering any water | 164 (13.1) | 336 (39.4) | 266 (89.9) | 70 (12.6) |

| Offering any milk | 131 (10.5) | 201 (23.6) | 180 (60.8) | 21 (3.8) |

| Offering any 100% juice | 140 (11.2) | 229 (26.9) | 204 (68.9) | 25 (4.5) |

| Offering any diet drinks | 153 (12.2) | 283 (33.2) | 240 (81.1) | 43 (7.7) |

| Offering any sugar-added drinks | 166 (13.2) | 339 (39.8) | 270 (91.2) | 69 (12.4) |

| Offering any alcohol | 123 (9.8) | 160 (18.8) | 152 (51.4) | 8 (1.4) |

| Offering only less-healthful drinksd | 2 (0.2) | 31 (3.6) | 20 (6.8) | 11 (2.0) |

Note: Some foods (e.g., live chickens, live goats, and fresh eggs, as offered from two livestock vendors) and drinks (e.g., coffee or tea) fell outside of the categorization scheme for specific food/drink items but were included in totals for Offering any food, Offering any drink, or Offering any food/drink.

Food businesses = a subset of all storefront businesses including various grocery stores, supermarkets, specialty food stores, restaurants, and free-standing vending machines (outlets primarily in the business of selling food/drink); Food businesses did not offer food in 100% of cases due to bars, night clubs, coffee shops, liquor stores, and vending machines that only offered drinks.

OSB = other storefront businesses, a subset of all storefront businesses comprised of outlets not primarily in the business of selling food/drink even though they might offer various kinds and quantitates. Among OSB offering food/drink were: auto repair and auto sales shops; banks and check cashing outlets; clothing, shoe, apparel, and jewelry stores; department stores; dollar stores and discount stores; electronics stores, furniture shops; gas stations, gift shops; gyms and fitness centers; hardware stores, impound/towing facilities, laundromats and dry cleaners; newsstands; pawn shops; pharmacies; phone stores; pet shops; professional offices (medical, legal, real estate, etc.); salons and barber shops; storage facilities; tanning salons; tattoo parlors; and tobacco shops.

Only less healthful foods = only refined sweets or salty/fatty fare; no healthful food options (i.e., no fruits or vegetables, whole grains, or nuts)

Only less-healthful drinks = only sugar-added drinks or alcohol; no healthful drinks (i.e., no water or milk). Note that 100% juice and diet drinks, were considered neither healthful nor less-healthful

Food/drink items were available on 14.7% of all street segments. In the 15 higher-poverty census tracts (those in the southwest Bronx; Figure 1), 36.7% of street segments offered some food/drink (data not shown). These higher-poverty census tracts had fewer than half as many street segments as the 17 lower-poverty census tracts, but had more than twice as many storefront businesses, resulting in a retail density that was nearly five times as great (Figure 1). Despite differences in the absolute numbers of businesses though, the proportion of businesses offering foods/drinks was similar in both groups of census tracts (about 50%).

For the entire sample of all 32 census tracts, more than half of all businesses (50.7%) offered some food/drink—100% of food businesses and 24.5% of OSB. Given OSB (n=556) were almost twice as numerous as food businesses (n=296), OSB represented 31.5% of all storefronts offering food/drink overall. Among the OSB that offered food/drink were auto shops, banks, clothing outlets, department stores, dollar stores, furniture shops, gyms, hardware stores, laundromats (example in Figure 2), professional offices, and salons (footnote b of Table 2 provides additional examples).

Figure 2.

Food/drink were often found in many surprising places (e.g., sandwiches in a laundromat).

When foods/drinks were available from businesses, there were healthier options in 81.7% of cases. Although 92.2% of food businesses offered healthful options, only 58.8% of the OSB that offered food/drink did. Examples of healthful options available from OSB included pieces of fresh and dried fruit, applesauce, canned vegetables, granola bars, whole-grain cereal, whole-wheat pretzels, peanuts, tree nuts, milk, and bottled water. OSB represented 22.7% of all businesses offering healthful options across all census tracts.

For less-healthful items, OSB represented 70.9% of all businesses offering only these items (e.g., sodas, energy drinks, candies, baked sweets, and snack chips). There were only four street segments on which less-healthful foods/drinks were the only available options (0.3% of the entire sample of street segments). Food businesses offered only less-healthful options in 7.8% of cases. OSB offered only less-healthful options in 10.1% of cases overall, but when considering just the OSB that offered any food/drink, the offering of only less-healthful options occurred in 41.2% of cases.

With regard to specific food categories, less-healthful foods (refined sweets, salty/fatty fare) were more prevalent than healthful foods (fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and nuts), both by street segment and by storefront business. Refined sweets (e.g., cookies, gumballs, lollipops, candy bars, other candies) were disproportionately more available from OSB.

For drinks, water was available more often from OSB than were sugar-added drinks. Of course, water would have been available for free in most restaurants (presumably with the purchase of some other item), so the lower proportion of businesses having water for sale does not fully reflect water’s total availability among food businesses. Milk was consistently more available than alcohol (by street segment, by food business, and by other business) although in some cases only available as an additive for purchased coffee or tea. Sugar-added drinks were the most available beverages by street segment and by storefront businesses.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to examine the availability of healthful and less-healthful foods/drinks from a full range of storefront businesses. Findings more fully characterize total food/drink availability in an urban environment.

As other researchers have suggested, food/drink in the local environment may indeed be “ubiquitous” . 9 In the current study, foods/drinks were available from half of all storefront businesses. About one quarter of OSB—including auto shops, banks, clothing outlets, gyms, hardware stores, laundromats, salons, and others—had food/drink items for sale. Given their prevalence in the environment, OSB represented nearly one third of all storefronts offering food/drink overall.

Sources of less-healthful items predominated, but at least some healthful options were available from more than four fifths of the businesses that offered any food/drink. OSB offered healthful items in well over half of the instances that they offered any food/drink, and they accounted for nearly one quarter of all the businesses offering healthful options. Given these findings, it is likely that determinations of food deserts would be inaccurate if OSB are not considered.

Businesses offering only less-healthful items were in the minority (outnumbered more than four to one by businesses offering at least some healthful options). Nonetheless, all businesses offering food/drink made less-healthful items available. When less-healthful options overwhelm healthier choices, those conditions define a food swamp,13 and such swamps might be underappreciated if all storefronts are not considered, and OSB are ignored. Prior research by others has shown more purchases of unhealthful items than healthful ones from OSB.30 OSB accounted for more than two thirds of the cases of storefronts offering only less-healthful items in the current study. Refined sweets stood out as the category offered most often.

A point of nuance for the current study is that it included only food/drink items available for purchase. Notable, though, is that nine beauty salons offered free candy and one furniture store offered free coffee (that could be customized with added milk and sweeteners). These items were not included in analyses; findings do not change meaningfully if they are.

Analyses in the current paper do include 20 businesses at which whole grains (e.g., brown rice, whole-wheat bagel, whole-grain pasta, and whole-wheat wraps) were available only upon asking and not obvious from menus, menu boards, signage, or displays. These businesses contributed to reported proportions of healthful foods in both areas, but would be “true exposures” in the food environment only for customers thinking to ask about unadvertised options. If uncounted in analyses, the removal of such items from healthful-food totals would only magnify the predominance of less-healthful items reported.

The current study has several strengths. First, investigators sampled in a diverse urban setting—with widely varying retail density in sociodemographically dissimilar communities—including all storefront businesses (totaling more than 850) on all streets (totaling more than1,250). Second, data collection considered both foods/drinks. Third, investigators assessed the availability of different varieties of both healthful and less-healthful items, and did not make problematic assumptions about healthfulness (e.g., assuming supermarkets are “healthy” food sources when they may be the predominant source of less-healthful items31). Fourth, food/drink availability was assessed using two different and complementary units of analysis: street segment (what’s available on a given street) and business (what’s available from a given storefront). Fifth, for businesses, investigators further refined categorization to distinguish between food businesses (the focus of most prior studies) and other business (neglected by most prior studies).1 The expansion in assessment represents an advance in scale and scope for food environment research.

Limitations

A notable limitation of the present study is the cross-sectional design. It is conceivable that findings could change with time. Indeed, some businesses that were closed at the time of assessment (e.g., some bars, night clubs, and table-service restaurants) would have been open at other times and would have offered foods/drinks as well. Still, the number of such businesses was small (less than 5% of businesses overall) and would not have changed findings meaningfully under any scenario. Other researchers have performed impressive longitudinal assessment of food environments,32 but such work considered only a very limited range of food stores and restaurants and failed to capture OSB (whose contribution might be quite substantial as the present study demonstrates). A study that included a full range of food sources (on a sample of streets from communities in present study), found there were nearly 30% more businesses offering food in 2015 than in 2010 (Lucan et al, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, as-yet unpublished observations, 2017).

Another limitation of the present study is that categorizations were generous with regard to healthfulness (e.g., counting sweetened trail mixes, sugared nuts, and popcorn as healthful items). Counting relatively minor ingredients like toppings for sandwiches and pizzas was also generous and there was no measure of the relative amount of healthful versus less-healthful items. Analyses considered only the number of food sources, not the number of food/drink items being offered (or purchased or consumed). Anecdotally, less-healthful items might have far exceeded healthier options in both quantity and variety in many, if not most, cases (e.g., a small basket of fresh fruit on the counter at a donut shop, or the single water option in a cooler full of sugary drinks). Thus, presented findings for healthful items should be interpreted as liberal, again underscoring the preponderance of less-healthful availability reported.

Although the data do not permit comment about generalizability with regard to other areas of New York or to other cities, the availability of less-healthful items from a wide variety of storefront retailers is consistent with prior literature looking at 19 U.S. cities.9 Also, the findings from the current study show consistency across highly different Bronx neighborhoods (those in ethnically and socioeconomically dissimilar communities having a nearly fivefold difference in the number of businesses on a given street). Other research has shown that foods/drinks offered by a specific type of other business (drug stores) do not vary by neighborhood income.8 The current study showed similar proportions in food/drink availability from OSB in spite of differing poverty rates between communities.

CONCLUSIONS

This study showed that foods/drinks were available from many surprising types of urban storefronts beyond the select stores and restaurants assessed in most studies. Less-healthful items predominated over healthier ones (across businesses and by street), but at least some healthful options were available in most cases.

Moving forward, food-environment studies should include OSB. Ignoring these businesses could mean missing more than one third of all sources of food/drink, possibly leading to incomplete findings and incorrect conclusions at best, and misguided interventions and wasted resources at worst.

Future studies should also consider additional sources of food/drink in neighborhoods, like street vendors and farmers markets.1,19,21,22 Delivery services may also be important,33 as well as all the messaging to consume foods/drinks, within stores7,34 and in neighborhoods.29,35,36 Product placement, price, and promotion across a range of possible food/drink sources are likewise relevant considerations that merit further investigation.37–39 Additionally, studies should assess how all of these food environment exposures may influence people’s purchasing and consumption patterns.

For communities, recognizing the substantial availability of foods/drinks from OSB will be important. OSB may already represent about one quarter of all storefront sources of healthful items. More of the businesses already offering food/drink might be persuaded to carry healthier options, both to reduce the number of food deserts (areas lacking healthier food) and to minimize food swamps (areas overwhelmed by junk food). Shelf-stable items (e.g., dried fruits, nuts, whole-grain snacks like crackers and trail mixes, vegetable chips, and bottled water) may hold particular promise for OSB, and for improving neighborhood food environments that are currently predominated by less-healthful foods/drinks.40

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Geohaira Sosa for her help with data cleaning and analysis; and Aixin Chen, Charles Pan, and Aurora Jin for reviewing drafts of the manuscript and providing insightful comments and contributions. The lead author is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of NIH under award K23HD079606. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. Student stipends through the Albert Einstein College of Medicine supported data collection. Data collection and management were through REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), hosted by the Harold and Muriel Block Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Einstein and Montefiore under grant UL1 TR001073. The authors have no financial disclosures.

SL conceived the study, performed the literature review, designed the data collection protocol, oversaw primary data collection, performed all analyses, and drafted the manuscript, including tables and figures. AM assisted with analyses and data interpretation, created the map, and helped revise the manuscript. JS, DY, and LS performed primary data collection, assisted with data analysis and interpretation, and helped revise the manuscript. CS oversaw and assisted with data analysis and helped revise the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lucan SC. Concerning limitations of food-environment research: a narrative review and commentary framed around obesity and diet-related diseases in youth. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(2):205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinnon RA, Reedy J, Morrissette MA, Lytle LA, Yaroch AL. Measures of the food environment: a compilation of the literature, 1990–2007. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4 suppl):S124–S133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lytle LA, Sokol RL. Measures of the food environment: A systematic review of the field, 2007–2015. Health Place. 2017;44:18–34. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspi CE, Pelletier JE, Harnack L, Erickson DJ, Laska MN. Differences in healthy food supply and stocking practices between small grocery stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(3):540–547. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015002724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laska MN, Caspi CE, Pelletier JE, Friebur R, Harnack LJ. Lack of healthy food in small-size to mid-size retailers participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E135. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Racine EF, Batada A, Solomon CA, Story M. Availability of foods and beverages in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-authorized dollar stores in a region of North Carolina. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(10):1613–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caspi CE, Lenk K, Pelletier JE, et al. Association between store food environment and customer purchases in small grocery stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0531-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Racine EF, Kennedy A, Batada A, Story M. Foods and beverages available at SNAP-authorized drugstores in sections of North Carolina. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(8):674–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.05.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farley TA, Baker ET, Futrell L, Rice JC. The ubiquity of energy-dense snack foods: a national multicity study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):306–311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright J, Kamp E, White M, Adams J, Sowden S. Food at checkouts in non-food stores: a cross-sectional study of a large indoor shopping mall. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(15):2786–2793. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon H, Scully M, Parkinson K. Pester power: snack foods displayed at supermarket checkouts in Melbourne, Australia. Health Promot J Austr. 2006;17(2):124–127. doi: 10.1071/HE06124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basch CH, Kernan WD, Menafro A. Presence of candy and snack food at checkout in chain stores: results of a pilot study. J Community Health. 2016;41(5):1090–1093. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooksey-Stowers K, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Food swamps predict obesity rates better than food deserts in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(11) doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hager ER, Cockerham A, O’Reilly N, et al. Food swamps and food deserts in Baltimore City, MD, USA: associations with dietary behaviours among urban adolescent girls. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(14):2598–2607. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016002123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. [Accessed February 22, 2018];NYC UHF 34 Neighborhoods. http://a816-dohbesp.nyc.gov/IndicatorPublic/EPHTPDF/uhf34.pdf.

- 16.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed June 22, 2017];S1701 Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_13_5YR_S1701&prodType=table.

- 17.NYC Health. [Accessed January 8, 2018];Community Health Survey. 2013 https://a816-healthpsi.nyc.gov/epiquery/CHS/CHSXIndex.html.

- 18.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed February 24, 2018];How the Census Bureau Measures Poverty. www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty/guidance/poverty-measures.html.

- 19.Lucan SC, Maroko A, Shanker R, Jordan WB. Green Carts (mobile produce vendors) in the Bronx--optimally positioned to meet neighborhood fruit-and-vegetable needs? J Urban Health. 2011;88(5):977–981. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9593-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucan SC, Varona M, Maroko AR, Bumol J, Torrens L, Wylie-Rosett J. Assessing mobile food vendors (a.k.a. street food vendors)--methods, challenges, and lessons learned for future food-environment research. Public Health. 2013;127(8):766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Bumol J, Varona M, Torrens L, Schechter CB. Mobile food vendors in urban neighborhoods-implications for diet and diet-related health by weather and season. Health Place. 2014;27:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Sanon O, Frias R, Schechter CB. Urban farmers’ markets: accessibility, offerings, and produce variety, quality, and price compared to nearby stores. Appetite. 2015;90:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Seitchik JL, Yoon D, Sperry LE, Schechter CB. Sources of Foods That Are Ready-to-Consume ('Grazing Environments') Versus Requiring Additional Preparation ('Grocery Environments'): Implications for Food-Environment Research and Community Health. J Community Health. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10900-018-0498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020: Eighth edition. [Accessed February 22, 2018];For Professionals: Recommendations At-A-Glance. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/resources/DGA_Recommendations-At-A-Glance.pdf. Published March 2016.

- 25.Nicklas T, Kleinman RE, O’Neil CE. Taking into account scientific evidence showing the benefits of 100% fruit juice. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):e4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301059. author reply e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wojcicki JM, Heyman MB. Reducing childhood obesity by eliminating 100% fruit juice. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1630–1633. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ludwig DS. Artificially sweetened beverages: cause for concern. JAMA. 2009;302(22):2477–2478. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Sanon OC, Schechter CB. Unhealthful food-and-beverage advertising in subway stations: targeted marketing, vulnerable groups, dietary intake, and poor health. J Urban Health. 2017;94(2):220–232. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenk KM, Caspi CE, Harnack L, Laska MN. Customer characteristics and shopping patterns associated with healthy and unhealthy purchases at small and non-traditional food stores. J Community Health. 2018;43(1):70–78. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0389-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaughan CA, Cohen DA, Ghosh-Dastidar M, Hunter GP, Dubowitz T. Where do food desert residents buy most of their junk food? Supermarkets. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(14):2608–2616. doi: 10.1017/S136898001600269X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rummo PE, Guilkey DK, Ng SW, Popkin BM, Evenson KR, Gordon-Larsen P. Beyond supermarkets: Food outlet location selection in four U.S. cities over time. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Niemeier HM, Wing RR. Home grocery delivery improves the household food environments of behavioral weight loss participants: results of an 8-week pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:58. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohri-Vachaspati P, Isgor Z, Rimkus L, Powell LM, Barker DC, Chaloupka FJ. Child-directed marketing inside and on the exterior of fast food restaurants. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yancey AK, Cole BL, Brown R, et al. A cross-sectional prevalence study of ethnically targeted and general audience outdoor obesity-related advertising. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):155–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesser LI, Zimmerman FJ, Cohen DA. Outdoor advertising, obesity, and soda consumption: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grier SA, Kumanyika SK. The context for choice: health implications of targeted food and beverage marketing to African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1616–1629. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen DA, Collins R, Hunter G, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Dubowitz T. Store impulse marketing strategies and body mass index. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(7):1446–1452. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Kleef E, Otten K, van Trijp HC. Healthy snacks at the checkout counter: a lab and field study on the impact of shelf arrangement and assortment structure on consumer choices. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1072. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lucan SC, Karpyn A, Sherman S. Storing empty calories and chronic disease risk: snack-food products, nutritive content, and manufacturers in Philadelphia corner stores. J Urban Health. 2010;87(3):394–409. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9453-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]