Abstract

Multiple independent cancer susceptibility loci at chromosome 8q24 have been identified by GWAS (Genome-wide association studies). Forty six articles including 60,293 cases and 62,971 controls were collected to conduct a meta-analysis to evaluate the associations between 21 variants in 8q24 and prostate cancer risk. Of the 21 variants located in 8q2\5 were significantly associated with the risk of prostate cancer. In particular, both homozygous AA and heterozygous CA genotypes of rs16901979, as well as the AA and CA genotypes of rs1447295, were associated with the risk of prostate cancer. Our study showed that variants in the 8q24 region are associated with prostate cancer risk in this large-scale research synopsis and meta-analysis. Further studies are needed to explore the role of the 8q24 variants involved in the etiology of prostate cancer.

Keywords: 8q24, genetic variant, prostate cancer, susceptibility, meta-analysis

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the commonest non-cutaneous malignancy in men all over the world. Based on epidemiological and biological data, there is growing evidence that many influencing factors, including geography, ethnicity, genetic factors, and so on(Rebbeck, 2017), are associated with the risk of PCa. PCa exhibits high heritability, however, the exact etiology of PCa is still unknown. Identification of genetic factors regulating the susceptibility and progression of PCa contributes to improvement of preventive measures and therapeutic outcomes.

Multiple risk loci for prostate cancer have been identified by GWAS. In 2007, a two-stage GWAS from 1,854 prostate cancer patients and 1,894 population-screened controls was conducted. In this study, common loci at 8q24 were identified to be associated with prostate cancer (Eeles et al., 2008). It was proved that 8q24 region was associated with lots of cancers, including breast (Pereira et al., 2016), prostate (Hubbard et al., 2016), bladder (Kiltie, 2010), colon (Ling et al., 2013), lung (Zhang et al., 2012), gliomas (Rice et al., 2013), and so on. These susceptibility loci actually do not affect coding DNA, interestingly, these loci showed strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) as they often tightly linked with many SNPs. However, further study found that there are many enhancers in 8q24 region, and the rs6983267-containing enhancer interacts with the MYC gene by binding with TCF7L2 (TCF4), and alter the sensitivity to WNT signaling (Tuupanen et al., 2009). Another recent study found that the rs378854-containing region can interact with the promoters of both MYC and MYC activator PVT1(Meyer et al., 2011). Based on the above compelling evidence, it was supposed that the 8q24 variants played important roles in prostate carcinogenesis.

Here we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis, involving a total of 60,293 cases and 62,971 controls, to evaluate all genetic studies that investigated associations between 15 variants in 8q24 and risk of prostate cancer.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We systematically searched PubMed and Embase to identify genetic association studies published in print or online before January 10th, 2018 in English language using key terms “8q24” and “polymorphism or variant or genotype” and “prostate carcinoma or prostate tumor or prostate cancer”. Two investigators (Yu Tong and Tao Yu) independently assessed the eligibility of each study. All studies included in this meta-analysis must meet all the following inclusion criteria: (i) evaluating the associations of the 8q24 variants with prostate cancer risk; (ii) providing sufficient data or multivariate-adjusted risk estimates [e.g., odds ratios (ORs), hazard ratios (HRs), relative risks (RRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or standard errors (SEs)] to calculate these estimates. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) insufficient data; (ii) they were published as letters to editors or conference abstracts; (iii) they were studies about cancer mortality.

Data extraction

Guidelines recommended were used to report meta-analyses of observational studies by an investigator (Yu Tong and Tao Yu) to extract data. Extracted data efrom each eligible study included name of first author, study design, publication date, source population, ethnicity, sample size, variants, alleles, and genotype counts, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) among controls. Ethnicity was classified as Caucasian, African, Asian, or others such as Latinos and Hawaiians. In this meta-analysis, 46 eligible publications are available with sufficient data.

Statistical analysis and assessment of cumulative evidence

For each study, the odds ratio (OR) was used as the metric of choice. Pooled odds ratios were computed by the fixed effects model and the random effects model based on heterogeneity estimates, according to Prof. Michael Borenstein's suggestion (Borenstein et al., 2010). Once an overall gene effect was confirmed, the genetic model-free approach suggested by Minelli et al. (2005) was used to estimate the genetic effects and mode of inheritance. Assessment of protection from bias also considered the magnitude of association. OR less than 1.15 implicated presence of bias, unless the association had been replicated prospectivelywith no evidence of publication bias by several studies, such as GWAS or GWAS meta-analysis from collaborative studies. Heterogeneity between studies was evaluated by Cochran's Q test and calculated I2 statistic h. I2-values < 25%, 25–50%, and > 50% represent no or little heterogeneity, moderate heterogeneity, and large heterogeneity, respectively. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine if exclusion of first published study deviated from HWE in controls influence the significant association. Harbord's test was performed to evaluate publication bias. Small study bias was calculated by egger's test. All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 14.0 (StataCorp, 2017), with the metan, metabias commands.

Results

Eligible studies

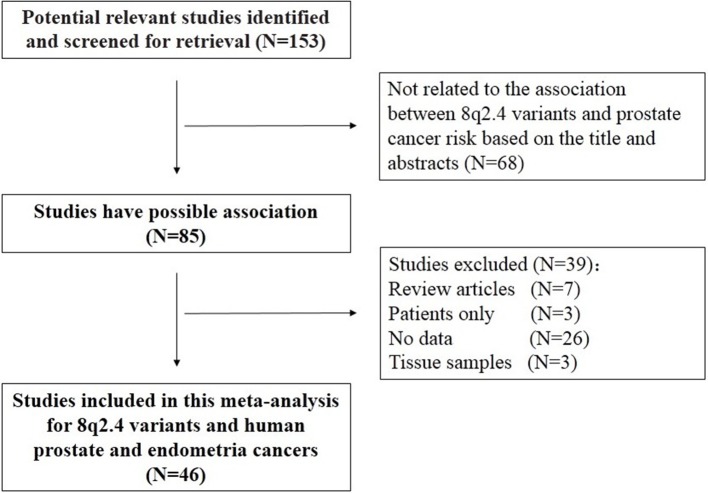

Our initial database search identified 268 potentially relevant studies. Based on a review of titles and abstracts, 85 articles were retained. The full text of these 85 articles was reviewed in detail, and 46 studies were eligible in this meta-analysis. The specific process for identifying eligible studies and inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included and excluded studies.

Allelic associations

Of the 21 variants located in 8q24, 15 were significantly associated with the risk of prostate cancer, including rs16901979, rs1447295, rs6983561, rs7000448, rs6983267, rs13254738, rs7017300, rs7837688, rs1016343, rs7008482, rs4242384, rs620861, rs10086908, DG8S737 Allele−8, and rs10090154. No significant associations were found between rs4242382, rs4645959, rs7837328, rs16901966, rs10505476, rs13281615 and prostate cancer (data not shown).

rs16901979 C>A

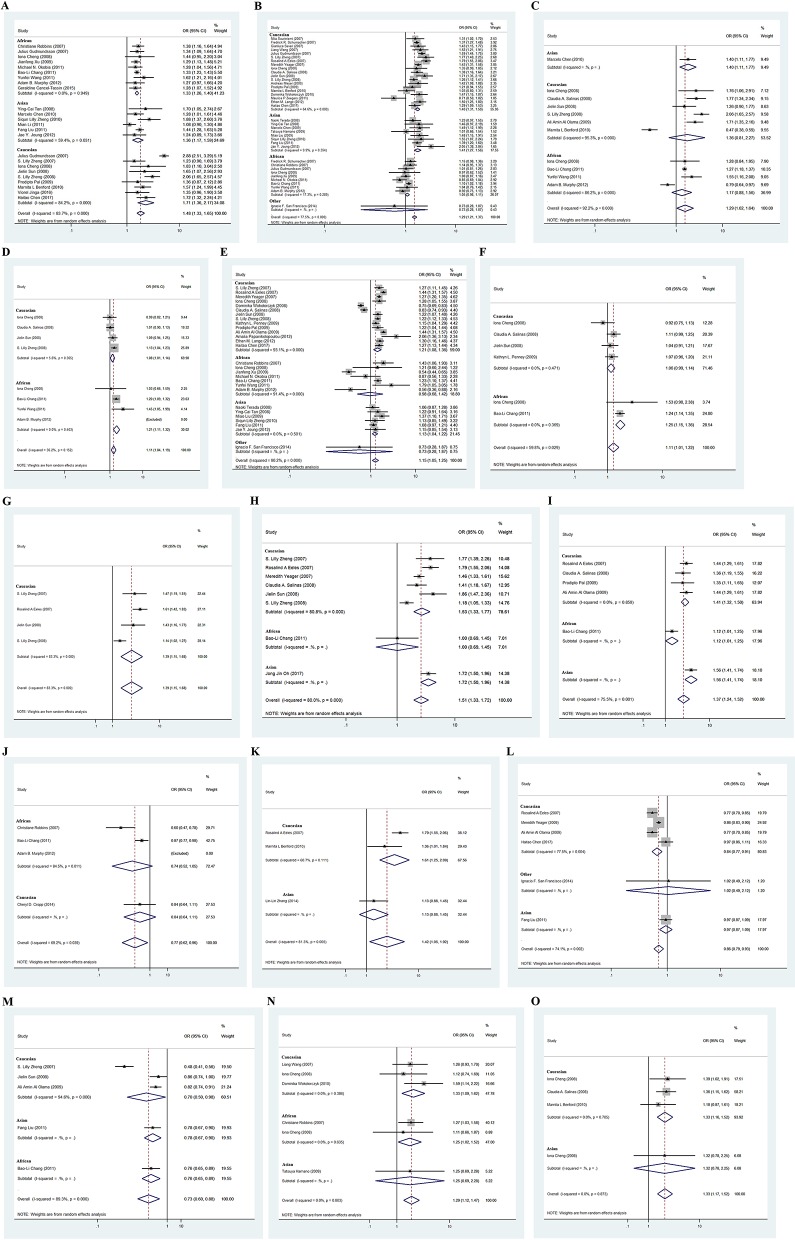

Twenty-four studies were included (Table 1), and a significant association with prostate cancer risk was found (p = 1.08 × 10−12, random effect OR = 1.48, 95% CI: 1.33, 1.65; Q = 141.34, p = 0.00, I2 = 83.7%, Figure 2A). A similar pattern was observed for Africans (p = 1.26 × 10−26, random effect OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.26, 1.40; Q = 2.76, p = 0.949, I2 = 0.0%), Asians (p = 8.49 × 10−5, random effect OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.17, 1.59; Q = 12.31, p = 0.031, I2 = 59.4%) and Caucasians (p = 6.48 × 10−6, random effect OR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.36, 2.17; Q = 50.60, p = 0.00, I2 = 84.2%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.757, Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included articles.

| Study, year | Study design | Country/region | Ethnicity | Variant | Cases/controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geraldine Cancel-Tassin, 2015 (Cancel-Tassin et al., 2015) | Population-based case–control study | France | African | rs16901979 | 489/534 |

| Mian Li, 2011 (Li et al., 2011) | Case–control study | China | Asian | rs16901979 | 432/782 |

| Maurice P Zeegers, 2011 (Zeegers et al., 2011) | Cohort Study | Netherlands | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 281/267 |

| Marcelo Chen, 2010 (Chen et al., 2010) | Case–control study | China | Asian | rs16901979 | 331/335 |

| rs6983561 | 324/336 | ||||

| Prodipto Pal, 2009 (Pal et al., 2009) | Case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs16901979 | 596/567 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs4645959 | |||||

| rs1016343 | |||||

| Marcelo Chen, 2009 (Chen et al., 2009) | Hospital-based case–control study | China | Asian | rs1447295 | 340/337 |

| Andreas Meyer, 2009 (Meyer et al., 2009) | Hospital-based case–control study | Germany | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 486/462 |

| rs13281615 | 488/462 | ||||

| Iona Cheng, 2008 (Cheng et al., 2008) | Case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs16901979 | 417/416 |

| African | 89/87 | ||||

| rs1447295 | 417/417 | ||||

| 89/89 | |||||

| DG8S737 | 416/417 | ||||

| 89/89 | |||||

| rs6983561 | 417/417 | ||||

| 88/89 | |||||

| rs10090154 | 417/414 | ||||

| 89/88 | |||||

| rs7000448 | 416/417 | ||||

| 89/89 | |||||

| rs6983267 | 417/417 | ||||

| 89/89 | |||||

| rs13254738 | 506/506 | ||||

| 89/88 | |||||

| Christiane Robbins, 2007 (Robbins et al., 2007) | Case–control study | USA | African | rs16901979 | 490/567 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| DG8S737 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs7008482 | |||||

| Miia Suuriniemi, 2007 (Suuriniemi et al., 2007) | Population-based case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 582/538 |

| Fredrick R. Schumacher, 2007 (Schumacher et al., 2007) | Nested case-control study | Multiple countries | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 5505/6270 |

| African | 676/643 | ||||

| Julius Gudmundsson, 2007 (Gudmundsson et al., 2007) | Case–control study | Iceland | Caucasian | rs16901979 | 2663/5509 |

| African | 373/372 | ||||

| Caucasian | rs1447295 | ||||

| African | |||||

| Gianluca Severi, 2007 (Severi et al., 2007) | Case–control study | Australia | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 821/732 |

| Dominika Wokołorczyk, 2008 (Wokolorczyk et al., 2008) | Case–control study | Poland | Caucasian | rs6983267 | 1910/1885 |

| S. Lilly Zheng, 2007 (Zheng et al., 2007) | Case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs16901979 | 1563/576 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs4242382 | |||||

| rs7017300 | |||||

| rs7837688 | |||||

| rs4645959 | |||||

| rs10086908 | |||||

| Jae Y. Joung, 2012 (Joung et al., 2012) | Hospital-based case–control study | Korea | Asian | rs16901979 | 194/169 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| Naoki Terada, 2008 (Terada et al., 2008) | Case–control study | Japanese | Asian | rs1447295 | 507/387 |

| rs6983267 | |||||

| Michael N. Okobia, 2011 (Okobia et al., 2011) | Case–control study | Caribbean | African | rs16901979 | 338/426 |

| rs1447295 | 354/438 | ||||

| rs6983267 | 343/426 | ||||

| Claudia A. Salinas, 2008 (Salinas et al., 2008) | Population-based case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 1252/1233 |

| rs6983561 | 1264/1236 | ||||

| rs10090154 | 1288/1250 | ||||

| rs7000448 | 1262/1239 | ||||

| rs6983267 | 1258/1238 | ||||

| rs13254738 | 1256/1234 | ||||

| rs7837688 | 1260/1241 | ||||

| rs4645959 | 1261/1238 | ||||

| rs1016343 | 1253/1233 | ||||

| rs7837328 | 1258/1239 | ||||

| rs16901966 | 1302/1260 | ||||

| rs10505476 | 1256/1233 | ||||

| rs7837328 | 1258/1239 | ||||

| rs13281615 | 1254/1234 | ||||

| Marnita L Benford, 2010 (Benford et al., 2010) | Case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs16901979 | 192/512 |

| rs1447295 | 189/523 | ||||

| rs6983561 | 186/908 | ||||

| rs10090154 | 189/505 | ||||

| rs4242382 | 193/1167 | ||||

| rs4242384 | 193/524 | ||||

| Siqun Lilly Zheng, 2010 (Zheng et al., 2010) | Population-based case–control study | China | Asian | rs16901979 | 283/145 |

| rs1447295 | 284/151 | ||||

| rs6983267 | 282/152 | ||||

| Rosalind A Eeles, 2007 (Eeles et al., 2008) | Population-based case–control study | United Kingdom | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 1906/1934 |

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs4242382 | |||||

| rs7017300 | |||||

| rs7837688 | |||||

| rs1016343 | |||||

| rs7837328 | |||||

| rs4242384 | |||||

| rs620861 | |||||

| rs16901966 | |||||

| rs7837328 | |||||

| Jielin Sun, 2008 (Sun et al., 2008) | Population-based case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs16901979 | 1625/560 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983561 | |||||

| rs10090154 | |||||

| rs7000448 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs13254738 | |||||

| rs4242382 | |||||

| rs7017300 | |||||

| rs7837688 | |||||

| rs10086908 | |||||

| Amalia Papanikolopoulou, 2011 (Papanikolopoulou et al., 2011) | Case–control study | Greece | Caucasian | rs6983267 | 86/99 |

| Kathryn L. Penney, 2009 (Penney et al., 2009) | Case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs6983267 | 1305/1402 |

| rs13254738 | |||||

| Liang Wang, 2007 (Wang et al., 2007) | Case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 1121/545 |

| DG8S737 | |||||

| S. Lilly Zheng, 2008 (Zheng et al., 2008) | Population-based case–control study | Sweden | Caucasian | rs16901979 | 2893/1781 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983561 | |||||

| rs10090154 | |||||

| rs7000448 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs4242382 | |||||

| rs7017300 | |||||

| rs7837688 | |||||

| Ying-Cai Tan, 2008 (Tan et al., 2008) | Case–control study | India | Asian | rs16901979 | 153/227 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| Viorel Jinga, 2016 (Jinga et al., 2016) | Case–control study | Romania | Caucasian | rs16901979 | 955/1007 |

| Cheryl D. Cropp, 2014 (Cropp et al., 2014) | Population-based case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs7008482 | 522/510 |

| Lin-Lin Zhang, 2014 (Zhang et al., 2014) | Case–control study | China | Asian | rs7837328 | 388/384 |

| rs4242384 | |||||

| Ignacio F. San Francisco, 2014 (San Francisco et al., 2014) | Case–control study | Chile | Hispanic | rs1447295 | 83/21 |

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs7837328 | |||||

| rs620861 | |||||

| Adam B. Murphy, 2012 (Murphy et al., 2012) | Case–control study | Cameroon | African | rs16901979 | 308/469 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983561 | |||||

| rs7000448 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs7008482 | |||||

| Fang Liu, 2011 (Liu et al., 2011) | Case–control study | China | Asian | rs16901979 | 1108/1525 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs620861 | |||||

| rs10086908 | |||||

| Ethan M. Lange, 2012 (Lange et al., 2012) | Case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 1176/1101 |

| rs6983267 | |||||

| Bao-Li Chang, 2011 (Chang et al., 2011) | Case–control study | USA | African | rs16901979 | 2642/2584 |

| rs1447295 | 3167/3325 | ||||

| rs6983561 | 2764/3255 | ||||

| rs10090154 | 1683/1403 | ||||

| rs7000448 | 1698/2329 | ||||

| rs6983267 | 3666/2992 | ||||

| rs13254738 | 2557/2277 | ||||

| rs4242382 | 1289/1527 | ||||

| rs7837688 | 636/330 | ||||

| rs1016343 | 1975/1830 | ||||

| rs7008482 | 2172/1760 | ||||

| rs7837328 | 473/772 | ||||

| rs10086908 | 861/876 | ||||

| rs16901966 | 861/875 | ||||

| rs10505476 | 473/744 | ||||

| rs7837328 | 473/772 | ||||

| Yunfei Wang, 2011 (Wang et al., 2011) | Case–control study | USA | African | rs16901979 | 127/345 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983561 | |||||

| rs10090154 | |||||

| rs7000448 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs4242382 | |||||

| Tatsuya Hamano, 2010 (Hamano et al., 2010) | Case–control study | Japan | Asian | rs1447295 | 158/119 |

| DG8S737 | |||||

| Dominika Wokołorczyk, 2010 (Wokolorczyk et al., 2010) | Hospital-based case–control study | Poland | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 690/602 |

| DG8S737 | |||||

| Meredith Yeager, 2009 (Yeager et al., 2009) | Case–control study | USA | Caucasian | rs620861 | 10286/9135 |

| rs13281615 | |||||

| Ali Amin Al Olama, 2009 (Al Olama et al., 2009) | Case–control study | United Kingdom | Caucasian | rs6983561 | 1906/1934 |

| rs10090154 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs1016343 | |||||

| rs620861 | |||||

| rs10086908 | |||||

| Miao Liu, 2009 (Liu et al., 2009) | Case–control study | Japan | Asian | rs1447295 | 391/323 |

| rs6983267 | |||||

| Jianfeng Xu, 2009 (Xu et al., 2009) | Case–control study | USA | African | rs16901979 | 868/878 |

| rs1447295 | |||||

| rs6983267 | |||||

| Joke Beuten, 2009 (Beuten et al., 2009) | Cohort Study | USA | Caucasian | rs10505476 | 601/840 |

| hispanic | 196/472 | ||||

| rs7837328 | |||||

| Meredith Yeager, 2007 (Yeager et al., 2007) | Cohort Study | USA | Caucasian | rs1447295 | 4296/4299 |

| rs6983267 | |||||

| rs7837688 | |||||

| Jong Jin Oh, 2017 (Oh et al., 2017) | Hospital-based case–control study | Caucasian | rs1016343 | 1001/2641 | |

| rs7837688 | |||||

| Haitao Chen, 2018 (Chen et al., 2018) | Case–control study | Caucasian | rs6983267 | 779/1643 | |

| rs620861 | |||||

| rs16901979 | |||||

| rs1447295 |

Figure 2.

Forest plots for associations between selected variants in the 8q24 region and prostate cancer risk. Associations of rs16901979 (A), rs1447295 (B), rs6983561 (C), rs7000448 (D), rs6983267 (E), rs13254738 (F), rs7017300 (G), rs7837688 (H), rs1016343 (I), rs7008482 (J), rs4242384 (K), rs620861 (L), rs10086908 (M), DG8S737 Allele−8 (N), and rs10090154 (O) with prostate cancer risk.

Table 2.

Details of genetic variants significantly associated with cancer risk in meta-analyses.

| Variants | Cancer risk | Initial study influence | Deviation from HWE | p-value for publication bias | p-value for small study bias | Genotype cancer risk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR1 (95% CI) | p-value | OR2 (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| rs16901979 | 1.48 (1.26–1.40) | 1.08 × 10−12 | 1.49(1.33–1.66) | 1.67 × 10−12 | No | 0.757 | 0.757 | 1.72(1.44–2.05) | 1.97 × 10−9 | 1.36(1.15–1.61) | 3.06 × 10−4 |

| rs1447295 | 1.29 (1.21–1.37) | 3.20 × 10−14 | 1.30 (1.21–1.39) | 9.94 × 10−15 | No | 0.559 | 0.664 | 1.42(1.10–1.82) | 0.006 | 1.31(1.18–1.45) | 3.06 × 10−7 |

| rs6983561 | 1.29 (1.02–1.64) | 0.036 | 1.29 (1.00–1.66) | 0.048 | No | 0.977 | 0.887 | 0.84(0.62–1.13) | 0.242 | 1.54(1.29–1.83) | 1.84 × 10−6 |

| rs7000448 | 1.11(1.04–1.19) | 0.003 | 1.11(1.03–1.20) | 0.004 | No | 0.868 | 0.889 | 0.98(0.80–1.21) | 0.867 | 1.04(0.90–1.20) | 0.64 |

| rs13254738 | 1.11(1.01–1.22) | 0.026 | 1.13(1.04–1.23) | 0.005 | No | 0.599 | 0.601 | 1.19(0.85–1.68) | 0.312 | 1.04(0.94–1.16) | 0.458 |

| rs6983267 | 1.15(1.05–1.25) | 0.003 | 1.14(1.04–1.25) | 0.006 | No | 0.577 | 0.583 | 1.31(0.92–1.86) | 0.134 | 1.05(0.5–1.22) | 0.546 |

| rs7017300 | 1.39(1.15–1.68) | 0.001 | 1.37(1.08–1.75) | 0.009 | No | 0.564 | 0.531 | ||||

| rs7837688 | 1.51(1.33–1.72) | 1.66 × 10−10 | 1.49(1.30–1.70) | 1.20 × 10−8 | No | 0.921 | 0.816 | ||||

| rs1016343 | 1.37(1.24–1.52) | 8.25 × 10−10 | 1.36(1.20–1.54) | 1.37 × 10−6 | No | 0.922 | 0.895 | ||||

| rs7008482 | 0.77(0.62–0.96) | 0.021 | 0.86(0.77–0.96) | 0.008 | No | 0.549 | 0.533 | ||||

| rs4242384 | 1.42(1.05–1.92) | 0.022 | 1.22(1.01–1.48) | 0.044 | No | 0.376 | 0.340 | ||||

| rs620861 | 0.86(0.79–0.94) | 3.57 × 10−4 | 0.89(0.81–0.97) | 0.007 | No | 0.791 | 0.795 | ||||

| rs10086908 | 0.73(0.60–0.88) | 0.001 | 0.81(0.76–0.86) | 1.66 × 10−10 | No | 0.339 | 0.428 | ||||

| DG8S737−8 allele | 1.29 (1.12–1.47) | 3.06 × 10−4 | 1.29 (1.09–1.54) | 0.004 | No | 0.592 | 0.648 | 0.83(0.29–2.38) | 0.733 | 1.25(0.98–1.59) | 0.068 |

| rs10090154 | 1.33 (1.17–1.52) | 2.04 × 10−5 | 1.33(1.16–1.52) | 3.63 × 10−5 | No | 0.641 | 0.668 | 1.34(0.82–2.19) | 0.245 | 1.40(1.2–1.62) | 1.24 × 10−5 |

rs1447295 C>A

Thirty-seven studies were included (Table 1), a significant association was found with the risk of prostate cancer (p = 3.20 × 10−14, random effect OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.21, 1.37; Q = 160.1, p = 0.00, I2 = 77.5%, Figure 2B). Significant association was also found for Asians (p = 2.08 × 10−11, random effect OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.27, 1.56; Q = 7.77, p = 0.354, I2 = 9.9%) and Caucasians (p = 2.52 × 10−23, random effect OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.31, 1.50; Q = 50.80, p = 0.00, I2 = 64.6%). However, no significant association was found for Africans (p = 0.168, random effect OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.11; Q = 9.68, p = 0.289, I2 = 17.3%), No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.587, Table 2).

rs6983561 A>C

Eleven studies were included (Table 1), a significant association was found with the risk of prostate cancer (p = 0.036, random effect OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.64; Q = 128.51, p = 0.00, I2 = 92.2%, Figure 2C). No significant association was found for Africans (p = 0.269, random effect OR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.88, 1.56; Q = 21.67, p = 0.000, I2 = 86.2%) and Caucasians (p = 0.241, random effect OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 0.81, 2.27; Q = 105.31, p = 0.00, I2 = 95.3%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.977, Table 2).

rs7000448 C>T

Eight studies were included (Table 1), a significant association was found with the risk of prostate cancer (p = 0.003, random effect OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.19; Q = 9.41, p = 0.152, I2 = 36.2%, Figure 2D). Further evaluation by ethnicity showed that significant association was found for Africans (p = 2.92 × 10−5, random effect OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.11, 1.32; Q = 1.82, p = 0.403, I2 = 0.0%) and Caucasians (p = 0.018, random effect OR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.14; Q = 3.18, p = 0.37, I2 = 5.6%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.868, Table 2).

rs6983267 T>G

Twenty-eight were included (Table 1), and a significant association with risk of prostate cancer was found (p = 0.003, random effect OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.25; Q = 275.92, p = 0.00, I2 = 90.2%, Figure 2E). A similar pattern was observed for Asians (p = 0.003, random effect OR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.22; Q = 4.35, p = 0.501, I2 = 0.0%) and Caucasians (p = 0.001, random effect OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.36; Q = 189.54, p = 0.00, I2 = 93.1%). No significant association was found for Africans (p = 0.269, random effect OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.68, 1.42; Q = 69.39, p = 0.000, I2 = 91.4%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.577, Table 2).

rs13254738 A>C

Six studies were included (Table 1), a significant association was found with the risk of prostate cancer (p = 0.026, random effect OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.22; Q = 12.44, p = 0.029, I2 = 59.8%, Figure 2F). Significant association was found for Caucasians (p = 0.08, random effect OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 0.99, 1.14; Q = 2.52, p = 0.47, I2 = 0.0%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.599, Table 2).

rs7017300 A>C

Four studies were included, a significant association with prostate cancer risk was found (p = 0.001, random effect OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.15, 1.68; Q = 17.93, p = 0.000, I2 = 83.3%, Figure 2G). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.564, Table 2).

rs7837688 G>T

Eight studies were included (Table 1), a significant association was found with the risk of prostate cancer (p = 1.66 × 10−10, random effect OR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.33, 1.72; Q = 35.02, p = 0.000, I2 = 80.0%, Figure 2H). Significant association was also found for Caucasians (p = 3.64 × 10−9, random effect OR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.33, 1.77; Q = 26.07, p = 0.000, I2 = 80.8%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.921, Table 2).

rs1016343 C>T

Six studies were included (Table 1), a significant association with risk of prostate cancer was found (p = 8.25 × 10−10, random effect OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.24, 1.52; Q = 20.42, p = 0.001, I2 = 75.5%, Figure 2I). Significant association was also found for Caucasians (p = 3.64 × 10−9, random effect OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.32, 1.50; Q = 0.76, p = 0.859, I2 = 0.0%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.922, Table 2).

rs7008482 G>T

Four studies were included (Table 1), a significant association was found with the risk of prostate cancer (p = 0.021, random effect OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.62, 0.96; Q = 6.49, p = 0.039, I2 = 69.2%, Figure 2J). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.549, Table 2).

rs4242384 A>C

Three studies were included (Table 1), a significant association with prostate cancer risk was found (p = 0.022, random effect OR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.92; Q = 10.71, p = 0.005, I2 = 81.3%, Figure 2K). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.376, Table 2).

rs620861 G>A

Six studies were included (Table 1), a significant association was found with the risk of prostate cancer (p = 3.57 × 10−4, random effect OR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.79, 0.94; Q = 19.28, p = 0.002, I2 = 74.1%, Figure 2L). Significant association was also found for Caucasians (p = 3.64 × 10−9, random effect OR = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.77, 0.91; Q = 13.34, p = 0.004, I2 = 77.5%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.791, Table 2).

rs10086908 T>C

Five studies were included (Table 1), a significant association was found with the risk of prostate cancer (p = 3.57 × 10−4, random effect OR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.60, 0.88; Q = 37.54, p = 0.000, I2 = 89.3%, Figure 2M). Significant association was also found for Caucasians (p = 0.036, random effect OR = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.50, 1.00; Q = 37.13, p = 0.004, I2 = 94.6%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.339, Table 2).

DG8S737 allele−8 absent>present

Five studies were included (Table 1), a significant association with risk of prostate cancer was found (p = 3.06 × 10−4, random effect OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.47; Q = 2.32, p = 0.803, I2 = 0.0%, Figure 2N). A similar pattern was observed for Caucasians (p = 0.005, random effect OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.62; Q = 1.91, p = 0.386, I2 = 0.0%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.592, Table 2).

rs10090154 C>T

Nine studies were included (Table 1), a significant association was found with the risk of prostate cancer (p = 2.04 × 10−5, random effect OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.17, 1.52; Q = 0.70, p = 0.873, I2 = 0.0%, Figure 2O). A similar pattern was observed for Caucasians (p = 3.63 × 10−5, random effect OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.16, 1.52; Q = 0.70, p = 0.705, I2 = 0.0%). No publication bias was found in the eligible studies (Harbord's test p = 0.641, Table 2).

Genotype comparison

rs16901979 C>A

Of the 24 studies, nine reported genotype information. The effects of genotype for AA vs. CC (OR1) and CA vs. CC (OR2) were calculated. Multivariate meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the pooled risk (Table 2). Individuals with the homozygous AA genotype (p = 3.86 × 10−9, random effect OR1 = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.43, 2.04; Q = 7.48, p = 0.486, I2 = 0.0%) and heterozygous CA genotype (p = 3.06 × 10−4, random effect OR2 = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.15, 1.61; Q = 14.29, p = 0.074, I2 = 44.0%) have increased risk of prostate cancer.

rs1447295 C>A

Of the 38 studies, 19 reported genotype information. The effects of genotype for AA vs. CC (OR1) and CA vs. CC (OR2) were calculated for each study (Table 2). Individuals with the homozygous AA genotype (p = 0.006, random effect OR1 = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.82; Q = 33.56, p = 0.010, I2 = 49.3%) and heterozygous CA genotype (p = 3.06 × 10−7, random effect OR2 = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.45; Q = 38.05, p = 0.002, I2 = 55.3%) have increased risk of prostate cancer.

rs6983561 A>C

Of the 11 studies, five reported genotype information. The genotype effects for CC vs. AA (OR1) and AC vs. AA (OR2) were calculated for each study (Table 2). There was a significantly increased risk of prostate cancer among individuals with heterozygous AC genotype (p = 1.84 × 10−6, random effect OR2 = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.29, 1.83; Q = 4.10, p = 0.393, I2 = 2.4%). However, no significant association was found among individuals with the homozygous CC genotype.

rs10090154 C>T

Of the 9 studies, four reported genotype information. The effects of genotype for TT vs. CC (OR1) and CT vs. CC (OR2) were calculated for each study (Table 2). Individuals with heterozygous CT genotype (p = 1.24 × 10−5, random effect OR2 = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.20, 1.62; Q = 1.58, p = 0.663, I2 = 0.0%) have an increased risk of prostate cancer. However, no significant association was found among individuals with the homozygous TT genotype.

Sensitivity analysis

Results of sensitivity analysis showed that the obtained results of 8q24 variants and risk of prostate cancer were robust statistically and no individual study affected the pooled OR significantly (Table 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the most comprehensive and largest evaluation of publications on associations between 8q24 variants and PCa risk. Preliminary meta-analyses mostly focused on the association between single or less SNPs with prostate cancer. From 46 eligible articles including 60,293 cases and 62,971 controls, we performed meta-analysis to evaluate associations between 15 variants in 8q24 region and PCa risk. Our study here provides an update of the previous reports. In addition, more variants were evaluated that have not been analyzed by meta-analyses previously.

Of the 21 variants located in 8q24, 15 were associated with prostate cancer risk significantly. Our primary analysis shows that, the rs16901979 (p = 1.08 × 10−12, OR = 1.48), rs1447295 (p = 4.51 × 10−15, OR = 1.29), rs6983561 (p = 0.036, OR = 1.29), rs7000448 (p = 0.003, OR = 1.11), rs6983267 (p = 0.003, OR = 1.15), rs13254738 (p = 0.026, OR = 1.11), rs7017300 (p = 0.001, OR = 1.39), rs7837688 (p = 1.66 × 10−10, OR = 1.51), rs1016343 (p = 8.25 × 10−10, OR = 1.37), rs7008482 (p = 0.021, OR = 0.77), rs4242384 (p = 0.022, OR = 1.42), rs620861 (p = 3.57 × 10−4, OR = 0.86), rs10086908 (p = 3.57 × 10−4, OR = 0.73), DG8S737 Allele-8 (p = 3.06 × 10−4, OR = 1.29), rs10090154 (p = 2.04 × 10−5, OR = 1.33) were significantly associated with PCa risk. In particular, both homozygous AA (p = 3.86 × 10−9, OR1 = 1.71) and heterozygous CA (p = 3.06 × 10−4, OR2 = 1.36) genotypes of rs16901979, as well as the AA (p = 0.005, OR1 = 1.41) and CA (p = 2.14 × 10−8, OR2 = 1.33) genotypes of rs1447295, were associated with PCa risk. Heterozygous AC genotype (p = 1.84 × 10−7, OR2 = 1.54) of rs6983561, CT genotype (p = 1.24 × 10−5, OR2 = 1.40) of rs10090154 were also found to be associated with the risk of PCa. Our findings were robust in regard to study design and sensitivity analyses according to several gene-variants-association studies and thousands of participants. No evidence of small study bias or publication bias was found.

The 8q24 region is dense with SNP (single-nucleotide-polymorphism) associated with risk for prostate, colorectal, breast cancer, et al. There are about five separated different cancer susceptibility loci specific for different cancers within the 8q24 “desert” (Huppi et al., 2012). Region 1, including rs16901979, rs13254738 and rs6983561, region 4, including rs7000448 and region 5, including rs1447295 specifically associated with the PCa risk, rs13281615 in region 2 is a breast-specific cancer susceptibility loci, rs10505477 and rs10808556 in a same block in region 3 were confirmed to be associated with colorectal cancer(Ghoussaini et al., 2008). Although the exact biological mechanisms underlying these associations with multiple cancers are confusing, these variants might affect tissue-specific enhancers of one or more genes involved in carcinogenesis. FAM84B, very closest to 8q24, is reported that, during prostate tumorigenesis and follows PCa progression, its expression increased (Wong et al., 2017). Another pseudogene of POU5F1P1/POU5F1B, located in 8q24.21 region, was also observed that levels of both the mRNA and protein increased in PCa (Kastler et al., 2010). Therefore, variants in 8q24 region themselves or with other variants might be responsible for the associations with prostate cancer.

Our study provides summary evidence that common 15 variants in the 8q24 region are associated with PCa risk. To explore the exact mechanisms of 8q24 variants involved in parthenogenesis of prostate cancer needs further functional studies.

Author contributions

Data were extracted by YT and TY. SL, FZ, and JY analyzed the data. YQ and DM wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81401238, 81330016, 81630038, 81771634), grants from the Ministry of Education of China (313037, 20110181130002), a grant from State Commission of Science Technology of China (2012BAI04B04), grants from the Science and Technology Bureau of Sichuan province (2012SZ0010, 2014SZ0149, 2016JY0028), and a grant from the clinical discipline program (Neonatology) from the Ministry of Health of China (1311200003303).

References

- Al Olama A. A., Kote-Jarai Z., Giles G. G., Guy M., Morrison J., Severi G., et al. (2009). Multiple loci on 8q24 associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 41, 1058–1060. 10.1038/ng.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benford M. L., VanCleave T. T., Lavender N. A., Kittles R. A., Kidd L. R. (2010). 8q24 sequence variants in relation to prostate cancer risk among men of African descent: a case-control study. BMC Cancer 10:334. 10.1186/1471-2407-10-334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuten J., Gelfond J. A., Martinez-Fierro M. L., Weldon K. S., Crandall A. C., Rojas-Martinez A., et al. (2009). Association of chromosome 8q variants with prostate cancer risk in Caucasian and Hispanic men. Carcinogenesis 30, 1372–1379. 10.1093/carcin/bgp148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L. V., Higgins J. P., Rothstein H. R. (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1, 97–111. 10.1002/jrsm.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancel-Tassin G., Romana M., Gaffory C., Blanchet P., Cussenot O., Multigner L. (2015). Region 2 of 8q24 is associated with the risk of aggressive prostate cancer in Caribbean men of African descent from Guadeloupe (French West Indies). Asian J. Androl. 17, 117–119. 10.4103/1008-682X.135127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B. L., Spangler E., Gallagher S., Haiman C. A., Henderson B., Isaacs W., et al. (2011). Validation of genome-wide prostate cancer associations in men of African descent. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 20, 23–32. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Ewing C. M., Zheng S., Grindedaal E. M., Cooney K. A., Wiley K., et al. (2018). Genetic factors influencing prostate cancer risk in Norwegian men. Prostate 78, 186–192. 10.1002/pros.23453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Huang Y. C., Ko I. L., Yang S., Chang Y. H., Huang W. J., et al. (2009). The rs1447295 at 8q24 is a risk variant for prostate cancer in Taiwanese men. Urology 74, 698–701. 10.1016/j.urology.2009.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Huang Y. C., Yang S., Hsu J. M., Chang Y. H., Huang W. J., et al. (2010). Common variants at 8q24 are associated with prostate cancer risk in Taiwanese men. Prostate 70, 502–507. 10.1002/pros.21084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng I., Plummer S. J., Jorgenson E., Liu X., Rybicki B. A., Casey G., et al. (2008). 8q24 and prostate cancer: association with advanced disease and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 16, 496–505. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cropp C. D., Robbins C. M., Sheng X., Hennis A. J., Carpten J. D., Waterman L., et al. (2014). 8q24 risk alleles and prostate cancer in African-Barbadian men. Prostate 74, 1579–1588. 10.1002/pros.22871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeles R. A., Kote-Jarai Z., Giles G. G., Olama A. A., Guy M., Jugurnauth S. K., et al. (2008). Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 40, 316–321. 10.1038/ng.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoussaini M., Song H., Koessler T., Al Olama A. A., Kote-Jarai Z., Driver K. E., et al. (2008). Multiple loci with different cancer specificities within the 8q24 gene desert. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100, 962–966. 10.1093/jnci/djn190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson J., Sulem P., Manolescu A., Amundadottir L. T., Gudbjartsson D., Helgason A., et al. (2007). Genome-wide association study identifies a second prostate cancer susceptibility variant at 8q24. Nat. Genet. 39, 631–637. 10.1038/ng1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamano T., Matsui H., Sekine Y., Ohtake N., Nakata S., Suzuki K. (2010). Association of SNP rs1447295 and microsatellite marker DG8S737 with familial prostate cancer and high grade disease. J. Urol. 184, 738–742. 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard G. K., Mutton L. N., Khalili M., McMullin R. P., Hicks J. L., Bianchi-Frias D., et al. (2016). Combined MYC activation and pten loss are sufficient to create genomic instability and lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 76, 283–292. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppi K., Pitt J. J., Wahlberg B. M., Caplen N. J. (2012). The 8q24 gene desert: an oasis of non-coding transcriptional activity. Front. Genet. 3:69. 10.3389/fgene.2012.00069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinga V., Csiki I. E., Manolescu A., Iordache P., Mates I. N., Radavoi D., et al. (2016). Replication study of 34 common SNPs associated with prostate cancer in the Romanian population. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 20, 594–600. 10.1111/jcmm.12729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung J. Y., Park S., Yoon H., Lee S. J., Park W. S., Seo H. K., et al. (2012). Association of common variations of 8q24 with the risk of prostate cancer in Koreans and a review of the Asian population. BJU Int. 110(6 Pt B), E318–E325. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastler S., Honold L., Luedeke M., Kuefer R., Möller P., Hoegel J., et al. (2010). POU5F1P1, a putative cancer susceptibility gene, is overexpressed in prostatic carcinoma. Prostate 70, 666–674. 10.1002/pros.21100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiltie A. E. (2010). Common predisposition alleles for moderately common cancers: bladder cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 20, 218–224. 10.1016/j.gde.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange E. M., Salinas C. A., Zuhlke K. A., Ray A. M., Wang Y., Lu Y., et al. (2012). Early onset prostate cancer has a significant genetic component. Prostate 72, 147–156. 10.1002/pros.21414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Zhou Y., Chen P., Yang H., Yuan X., Tajima K., et al. (2011). Genetic variants on chromosome 8q24 and colorectal neoplasia risk: a case-control study in China and a meta-analysis of the published literature. PLoS ONE 6:e18251. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H., Spizzo R., Atlasi Y., Nicoloso M., Shimizu M., Redis R. S., et al. (2013). CCAT2, a novel noncoding RNA mapping to 8q24, underlies metastatic progression and chromosomal instability in colon cancer. Genome Res. 23, 1446–1461. 10.1101/gr.152942.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Hsing A. W., Wang X., Shao Q., Qi J., Ye Y., et al. (2011). Systematic confirmation study of reported prostate cancer risk-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms in Chinese men. Cancer Sci. 102, 1916–1920. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02036.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Kurosaki T., Suzuki M., Enomoto Y., Nishimatsu H., Arai T., et al. (2009). Significance of common variants on human chromosome 8q24 in relation to the risk of prostate cancer in native Japanese men. BMC Genet. 10:37. 10.1186/1471-2156-10-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A., Schürmann P., Ghahremani M., Kocak E., Brinkhaus M. J., Bremer M., et al. (2009). Association of chromosomal locus 8q24 and risk of prostate cancer: a hospital-based study of German patients treated with brachytherapy. Urol. Oncol. 27, 373–376. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. B., Maia A. T., O'Reilly M., Ghoussaini M., Prathalingam R., Porter-Gill P., et al. (2011). A functional variant at a prostate cancer predisposition locus at 8q24 is associated with PVT1 expression. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002165. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minelli C., Thompson J. R., Abrams K. R., Lambert P. C. (2005). Bayesian implementation of a genetic model-free approach to the meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Stat. Med. 24, 3845–3861. 10.1002/sim.2393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A. B., Ukoli F., Freeman V., Bennett F., Aiken W., Tulloch T., et al. (2012). 8q24 risk alleles in West African and Caribbean men. Prostate 72, 1366–1373. 10.1002/pros.22486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J. J., Lee S. J., Hwang J. Y., Kim D., Lee S. E., Hong S. K., et al. (2017). Exome-based genome-wide association study and risk assessment using genetic risk score to prostate cancer in the Korean population. Oncotarget 8, 43934–43943. 10.18632/oncotarget.16540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okobia M. N., Zmuda J. M., Ferrell R. E., Patrick A. L., Bunker C. H. (2011). Chromosome 8q24 variants are associated with prostate cancer risk in a high risk population of African ancestry. Prostate 71, 1054–1063. 10.1002/pros.21320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal P., Xi H., Guha S., Sun G., Helfand B. T., Meeks J. J., et al. (2009). Common variants in 8q24 are associated with risk for prostate cancer and tumor aggressiveness in men of European ancestry. Prostate 69, 1548–1556. 10.1002/pros.20999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanikolopoulou A., Landt O., Ntoumas K., Bolomitis S., Tyritzis S. I., Constantinides C., et al. (2011). The multi-cancer marker, rs6983267, located at region 3 of chromosome 8q24, is associated with prostate cancer in Greek patients but does not contribute to the aggressiveness of the disease. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 50, 379–385. 10.1515/CCLM.2011.778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penney K. L., Salinas C. A., Pomerantz M., Schumacher F. R., Beckwith C. A., Lee G. S., et al. (2009). Evaluation of 8q24 and 17q risk loci and prostate cancer mortality. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 3223–3230. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira B., Chin S. F., Rueda O. M., Vollan H. K., Provenzano E., Bardwell H. A., et al. (2016). The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refines their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nat. Commun. 7:11479. 10.1038/ncomms11479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebbeck T. R. (2017). Prostate cancer genetics: variation by race, ethnicity, and geography. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 27, 3–10. 10.1016/j.semradonc.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice T., Zheng S., Decker P. A., Walsh K. M., Bracci P., Xiao Y., et al. (2013). Inherited variant on chromosome 11q23 increases susceptibility to IDH-mutated but not IDH-normal gliomas regardless of grade or histology. Neuro-oncology 15, 535–541. 10.1093/neuonc/nos324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins C., Torres J. B., Hooker S., Bonilla C., Hernandez W., Candreva A., et al. (2007). Confirmation study of prostate cancer risk variants at 8q24 in African Americans identifies a novel risk locus. Genome Res. 17, 1717–1722. 10.1101/gr.6782707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas C. A., Kwon E., Carlson C. S., Koopmeiners J. S., Feng Z., Karyadi D. M., et al. (2008). Multiple independent genetic variants in the 8q24 region are associated with prostate cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 17, 1203–1213. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Francisco I. F., Rojas P. A., Torres-Estay V., Smalley S., Cerda-Infante J., Montecinos V. P., et al. (2014). Association of RNASEL and 8q24 variants with the presence and aggressiveness of hereditary and sporadic prostate cancer in a Hispanic population. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 18, 125–133. 10.1111/jcmm.12171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher F. R., Feigelson H. S., Cox D. G., Haiman C. A., Albanes D., Buring J., et al. (2007). A common 8q24 variant in prostate and breast cancer from a large nested case-control study. Cancer Res. 67, 2951–2956. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severi G., Hayes V. M., Padilla E. J., English D. R., Southey M. C., Sutherland R. L., et al. (2007). The common variant rs1447295 on chromosome 8q24 and prostate cancer risk: results from an Australian population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 16, 610–612. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Lange E. M., Isaacs S. D., Liu W., Wiley K. E., Lange L., et al. (2008). Chromosome 8q24 risk variants in hereditary and non-hereditary prostate cancer patients. Prostate 68, 489–497. 10.1002/pros.20695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suuriniemi M., Agalliu I., Schaid D. J., Johanneson B., McDonnell S. K., Iwasaki L., et al. (2007). Confirmation of a positive association between prostate cancer risk and a locus at chromosome 8q24. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 16, 809–814. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y. C., Zeigler-Johnson C., Mittal R. D., Mandhani A., Mital B., Rebbeck T. R., et al. (2008). Common 8q24 sequence variations are associated with Asian Indian advanced prostate cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 17, 2431–2435. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada N., Tsuchiya N., Ma Z., Shimizu Y., Kobayashi T., Nakamura E., et al. (2008). Association of genetic polymorphisms at 8q24 with the risk of prostate cancer in a Japanese population. Prostate 68, 1689–1695. 10.1002/pros.20831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuupanen S., Turunen M., Lehtonen R., Hallikas O., Vanharanta S., Kivioja T., et al. (2009). The common colorectal cancer predisposition SNP rs6983267 at chromosome 8q24 confers potential to enhanced Wnt signaling. Nat. Genet. 41, 885–890. 10.1038/ng.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., McDonnell S. K., Slusser J. P., Hebbring S. J., Cunningham J. M., Jacobsen S. J., et al. (2007). Two common chromosome 8q24 variants are associated with increased risk for prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 2944–2950. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Ray A. M., Johnson E. K., Zuhlke K. A., Cooney K. A., Lange E. M. (2011). Evidence for an association between prostate cancer and chromosome 8q24 and 10q11 genetic variants in African American men: the Flint Men's Health Study. Prostate 71, 225–231. 10.1002/pros.21234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wokolorczyk D., Gliniewicz B., Sikorski A., Zlowocka E., Masojc B., Debniak T., et al. (2008). A range of cancers is associated with the rs6983267 marker on chromosome 8. Cancer Res. 68, 9982–9986. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wokołorczyk D., Gliniewicz B., Stojewski M., Sikorski A., Złowocka E., Debniak T., et al. (2010). The rs1447295 and DG8S737 markers on chromosome 8q24 and cancer risk in the Polish population. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 19, 167–171. 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32832945c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong N., Gu Y., Kapoor A., Lin X., Ojo D., Wei F., et al. (2017). Upregulation of FAM84B during prostate cancer progression. Oncotarget 8, 19218–19235. 10.18632/oncotarget.15168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Kibel A. S., Hu J. J., Turner A. R., Pruett K., Zheng S. L., et al. (2009). Prostate cancer risk associated loci in African Americans. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 18, 2145–2149. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager M., Chatterjee N., Ciampa J., Jacobs K. B., Gonzalez-Bosquet J., Hayes R. B., et al. (2009). Identification of a new prostate cancer susceptibility locus on chromosome 8q24. Nat. Genet. 41, 1055–1057. 10.1038/ng.444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager M., Orr N., Hayes R. B., Jacobs K. B., Kraft P., Wacholder S., et al. (2007). Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer identifies a second risk locus at 8q24. Nat. Genet. 39, 645–649. 10.1038/ng2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeegers M. P., Khan H. S., Schouten L. J., van Dijk B. A., Goldbohm R. A., Schalken J., et al. (2011). Genetic marker polymorphisms on chromosome 8q24 and prostate cancer in the Dutch population: DG8S737 may not be the causative variant. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 118–120. 10.1038/ejhg.2010.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. L., Sun L., Zhu X. Q., Xu Y., Yang K., Yang F., et al. (2014). rs10505474 and rs7837328 at 8q24 cumulatively confer risk of prostate cancer in Northern Han Chinese. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 15, 3129–3132. 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.7.3129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Chen Q., He C., Mao W., Zhang L., Xu X., et al. (2012). Polymorphisms on 8q24 are associated with lung cancer risk and survival in Han Chinese. PLoS ONE 7:e41930. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S. L., Hsing A. W., Sun J., Chu L. W., Yu K., Li G., et al. (2010). Association of 17 prostate cancer susceptibility loci with prostate cancer risk in Chinese men. Prostate 70, 425–432. 10.1002/pros.21076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S. L., Sun J., Cheng Y., Li G., Hsu F. C., Zhu Y., et al. (2007). Association between two unlinked loci at 8q24 and prostate cancer risk among European Americans. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99, 1525–1533. 10.1093/jnci/djm169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S. L., Sun J., Wiklund F., Smith S., Stattin P., Li G., et al. (2008). Cumulative association of five genetic variants with prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 910–919. 10.1056/NEJMoa075819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]