Significance

Reading of the genetic code is an intricate process in which the ribosome plays an active role in ensuring that translation proceeds rapidly and accurately. Studies have revealed that the mRNA adopts an unusual structure between the P and A sites of the small ribosomal subunit, where it is significantly kinked. In this work we probed the role of the kink structure in decoding. Substitutions that disrupt this structure were found to increase the accuracy of decoding. Conversely, peptide-bond formation on difficult-to-decode codons was severely reduced when this kink structure was perturbed. Our data suggest that the rigid nature of the mRNA backbone is important for ensuring efficient codon–anticodon interactions under suboptimal conditions.

Keywords: ribosome, decoding, mRNA structure, tRNA selection, phosphorothioate substitution

Abstract

During translation, the ribosome plays an active role in ensuring that mRNA is decoded accurately and rapidly. Recently, biochemical studies have also implicated certain accessory factors in maintaining decoding accuracy. However, it is currently unclear whether the mRNA itself plays an active role in the process beyond its ability to base pair with the tRNA. Structural studies revealed that the mRNA kinks at the interface of the P and A sites. A magnesium ion appears to stabilize this structure through electrostatic interactions with the phosphodiester backbone of the mRNA. Here we examined the role of the kink structure on decoding using a well-defined in vitro translation system. Disruption of the kink structure through site-specific phosphorothioate modification resulted in an acute hyperaccurate phenotype. We measured rates of peptidyl transfer for near-cognate tRNAs that were severely diminished and in some instances were almost 100-fold slower than unmodified mRNAs. In contrast to peptidyl transfer, the modifications had little effect on GTP hydrolysis by elongation factor thermal unstable (EF-Tu), suggesting that only the proofreading phase of tRNA selection depends critically on the kink structure. Although the modifications appear to have no effect on typical cognate interactions, peptidyl transfer for a tRNA that uses atypical base pairing is compromised. These observations suggest that the kink structure is important for decoding in the absence of Watson–Crick or G–U wobble base pairing at the third position. Our findings provide evidence for a previously unappreciated role for the mRNA backbone in ensuring uniform decoding of the genetic code.

The accurate decoding of the genetic code depends critically on the ability of the ribosome to select the aminoacyl tRNA (aa-tRNA) that matches the mRNA in its A site. During this process of tRNA selection, the ribosome employs multiple strategies to maintain the low error frequency of 10−4–10−3 per one amino acid-incorporation event (1–4). The aa-tRNA is delivered to the ribosome in a ternary complex with elongation factor thermal unstable (EF-Tu) and GTP. The hydrolysis of GTP by EF-Tu essentially divides the tRNA selection processes into two stages: initial selection and proofreading (5). Dividing the selection process gives the ribosome two opportunities to reject the incorrect aa-tRNA. This mechanism of kinetic proofreading (6, 7) utilizes both thermodynamic differences and induced fit to accelerate the dissociation rates of incorrect aa-tRNAs and forward rates for correct aa-tRNAs (8–10). In particular, during the initial selection phase, near-cognate ternary complexes rapidly fall off the ribosome, whereas GTP is rapidly hydrolyzed for cognate ternary complexes. Similarly, during the proofreading phase following the dissociation of EF-Tu, near-cognate aa-tRNAs are readily rejected, whereas cognate aa-tRNAs are readily accommodated into the active site to participate in peptidyl transfer (PT) (8).

More than half a century of biochemical studies on the ribosome have defined many of the molecular elements responsible for the observed accuracy during protein synthesis (reviewed in ref. 11). The ribosome itself plays a critical role in dictating the overall fidelity of this process (12, 13). Indeed, some of the first error-prone and hyperaccurate mutations to be identified mapped to ribosomal proteins. For instance, many mutations in the ribosomal protein genes rpsD and rpsE have long been documented to confer a ribosome ambiguity phenotype (ram) (14–19). On the other hand, mutations in the rpsL gene result in a restrictive phenotype. Most of these mutations also confer resistance to, or in some cases dependence on, the error-inducing antibiotic streptomycin (20, 21). In contrast to ribosomal proteins, mutations to the rRNA rarely appear naturally, due to incomplete penetrance of these mutations, as rRNA genes are typically found in numerous copies in the genome. Nonetheless, screens using high-copy plasmids carrying the rrn operon of Escherichia coli have been used to isolate rRNA variants that alter the decoding properties of the ribosome (22, 23). More recent studies using orthogonal ribosomes have also been successful in isolating mutants that otherwise would be dominant negative. Interestingly, most of these mutations appear to map to functionally important parts of the ribosome such as the decoding center or intersubunit bridges (24).

In addition to the ribosome, translation factors play a critical role in maintaining the fidelity of protein synthesis. For example, mutations in elongation and release factors (RFs) have been found to increase the error frequency during translation (25, 26). In addition, tRNAs arguably play one of the most important roles in the decoding process during both the aminoacylation reaction and the tRNA selection process. This is best exemplified by suppressor tRNAs that decode stop codons and result in missense suppression. While the miscoding properties of most of these RNAs can be easily rationalized by alteration to the anticodon, which allows them to base pair with the incorrect codon, some, in which mutations far from the anticodon appear to be responsible for their phenotype, are more complex. For instance, the Hirsch tRNATrp suppressor tRNA (CCA anticodon) harbors a G24A mutation in the D arm enabling it to decode the tryptophan UGG and UGA stop codons (27). Biochemical studies of this tRNA showed that this variant tRNA accelerates forward rates of tRNA selection even in the presence of mismatched codon–anticodon interaction, underlining the critical role of the tRNA during the selection process (28).

Emerging from recent structural studies of ribosomal complexes are some key hints about the molecular mechanics of the decoding process and how perturbation of the translation machinery disrupts them (29, 30). In particular, during the tRNA selection process, the decoding center of the ribosome undergoes local conformational changes that in turn drive larger changes within the small ribosomal subunit (31, 32). This so-called “domain closure” of the small subunit is also accompanied by changes to the A-site tRNA that are manifested by a large conformational change in its structure. This structural change is likely responsible for relaying a signal to the GTPase activation center of the large ribosomal subunit, leading to the subsequent accommodation of the tRNA into the peptidyl-transferase center (33, 34). These structures also provided some important mechanistic clues about how classic mutations in the ribosome perturb decoding. They appear to alter the thermodynamics of the interchangeability between the open and closed state of the ribosome (32). The rpsD and rpsE mutations of error-prone ribosomes disrupt interactions that are necessary to maintain the open conformation, whereas the rpsL mutations of hyperaccurate ribosomes disrupt interactions necessary for the closed conformation. In addition to the ribosome, the accompanying conformational changes in the tRNA as it moves into the A site play an integral role during protein synthesis (33, 35). Structural studies of the Hirsch suppressor tRNA revealed that tRNA distortion was critical for decoding (36). This increased flexibility of the tRNA allows increased GTPase activation of EF-Tu even in the presence of a near-cognate tRNA (28).

What is clear from the abundance of biochemical and structural studies on the ribosome is that decoding is an intricate process that takes cues from almost every single factor of the translation machinery. What has been less understood is the extent to which the structure of the mRNA itself is important for this process. Nonetheless, biochemical studies of the role of the mRNA ribose backbone during decoding showed that the substitutions of A-site 2′-OH residues with deoxy or fluoro groups had minimal impact on tRNA selection (37). This is in contrast to structural studies, which showed that the hydroxyl groups are important for A-minor interactions with the decoding center nucleotides (31, 32).

Equivalent studies of the role of the mRNA phosphodiester backbone on ribosome function are lacking. Interestingly, crystal structures of the ribosome revealed the mRNA adopts a kink-like structure between the P and A sites (38, 39). A magnesium ion stabilizes this structure through electrostatic interactions with the nonbridging oxygens of the phosphodiester backbone of the mRNA (39). While the kink has been speculated to be critical for frame maintenance by preventing slippage (39), this has not been tested directly. Whether the structure contributes to tRNA selection is unknown. Here, we perturbed the mRNA structure by introducing stereospecific phosphorothioate substitutions in the mRNA at the interface of the P and A sites and assessed their effect on decoding using a well-defined in vitro system. We found that substitution of either of the nonbridging oxygens results in a hyperaccurate phenotype; however, replacing the proSp oxygen, one of the oxygens involved in coordinating the divalent metal, with sulfur has a more drastic effect. In the presence of the Rp-phosphorothioate, PT rates for near-cognate aa-tRNAs were reduced by about 10-fold relative to the native mRNA. In contrast, the same rates were more than 100-fold slower for the Sp-phosphorothioate. Peptide release on near-stop codons was similarly affected, suggesting that the kink is critical for the process by which A-site ligands interact with the ribosome. In an effort to determine whether the substitutions affect both phases of tRNA selection, we measured the rates of GTP hydrolysis by near-cognate ternary complexes in the presence of the modifications. Either substitution resulted in a modest two- to threefold reduction in the observed rate, suggesting that magnesium coordination by the mRNA is important only for the proofreading phase of the selection process. Interestingly, while both substitutions appear to have no effect on most cognate aa-tRNA selection, the Sp-phosphorothioate substitution significantly reduced the PT rate for a difficult-to-decode cognate codon. In particular, PT for the AUA codon, which is decoded by the anticodon-modified Ile-tRNAIle(k2CAU), is approximately fivefold slower in the presence of Sp-modified mRNA than in the unmodified or the Rp-modified mRNAs. Finally, to expand on the potential role of the mRNA backbone on tRNA selection, we investigated the effect of the deoxy substitutions on peptide-bond formation for cognate and near-cognate ternary complexes. Similar to previous observations (37), substitution of any of the three 2′-OH groups of the A-site codon by a deoxy does not alter peptide-bond formation in the presence of a cognate aa-tRNA. However, peptide-bond formation was drastically inhibited for these modified mRNAs in the presence of a near-cognate aa-tRNA. Collectively our findings provide hints about the integral role of the mRNA structure in decoding and how its perturbation could have profound consequences on the speed of protein synthesis.

Results

Experimental Approach.

To investigate the role of the mRNA-kink structure in tRNA selection, we decided to destabilize magnesium binding at the interface of the P and A sites of the small subunit. The divalent metal ion is held in place by a network of electrostatic interactions that include three nonbridging oxygen atoms of the mRNA phosphodiester backbone (Fig. 1A). As a starting point, we chose to introduce sulfur substitutions between the initiation codon and the second codon of a model mRNA. Namely, we sought to substitute the proSp oxygen of the phosphodiester linkage between the third nucleotide of the P-site codon and the first nucleotide of the A-site codon (Fig. 1A). However, since the smallest model mRNA (∼25 nt) is too long to efficiently separate the two diastereomers resulting from chemical synthesis, we chose to generate the mRNAs from two pieces. This allowed us to synthesize the phosphorothioate-containing RNA as a 9-mer, which is readily separated into the Rp and Sp diastereomers using reverse-phase HPLC methods (Fig. 1B). Subsequent near-quantitative ligation using T4 RNA ligase 2 to an upstream RNA oligonucleotide containing the necessary Shine–Dalgarno sequence gave us the full-length model mRNA (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Structure of the mRNA on the ribosome and preparation of phosphorothioate-modified mRNAs. (A) Overview of the mRNA structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 2J00] highlighting the kink structure dividing the P and A sites of the ribosome. The nonbridging oxygen atoms (red) coordinating a magnesium ion (green) are shown. (B) A representative HPLC chromatogram showing the separation of the two phosphorothioate diastereoisomers of the downstream RNA sequence. (C) Schematic of the procedure used to synthesize the full-length modified mRNA. (Upper) Sequences of the two pieces are shown annealed to a DNA splint. (Lower) A representative denaturing PAGE used to follow the ligation reaction using a radiolabeled downstream sequence.

The modified mRNA was then used in our in vitro reconstituted system (40) to make initiation complexes. Ribosomes were incubated with initiation factors (IFs) 1, 2, and 3, f-[35S]-Met-tRNAfMet, and GTP in the presence of native or modified mRNAs. The initiation complexes were then purified away from the IFs and unbound mRNA through ultracentrifugation over a sucrose cushion. The first set of initiation complexes displayed the Glu GAA codon. Peptide-bond formation was commenced by incubating initiation complexes with ternary complexes comprised of aa-tRNA, EF-Tu, and GTP. Following quenching and hydrolysis of the ester linkage between the peptide and the tRNA with KOH, dipeptides were resolved from unreacted fMet using electrophoretic TLC and were visualized by phosphorimaging.

Phosphorothioate Substitutions at the Interface of the P and A Sites Result in Stringent tRNA Selection.

For our initial studies we conducted a surveying approach (41) in an effort to gain an unbiased view of the modifications’ effects on the decoding process. Three initiation complexes programmed with the native mRNA or with Rp- or Sp-phosphorothioate–modified mRNAs were reacted with the 20 canonical aa-tRNA isoacceptors for 30 s (Fig. 2). As expected, all three complexes, which displayed the GAA codon in the A site, reacted efficiently with the cognate Glu-tRNAGlu ternary complex. In contrast, replacement of either of the nonbridging oxygen atoms by sulfur had a profound effect on the reactivity of near-cognate ternary complexes. In particular, whereas dipeptide formation was observed for a number of near-cognate aa-tRNAs (including but not limited to Asp-tRNAAsp and Lys-tRNALys) in the presence of the native complex (O), significantly less dipeptide was observed in the presence of the Rp complex, and it was nearly undetectable for the Sp complex (Fig. 2). These observations suggested that the structure of the mRNA backbone, particularly at the interface of the A and P sites of the ribosome, plays an important role during tRNA selection.

Fig. 2.

Phosphorothioate mRNAs suppress the incorporation of near-cognate amino acids PhosphorImager scans of electrophoretic TLCs showing the reactivity profile of the initiation complexes programmed with the indicated native and phosphorothioate-modified mRNAs with the 20 aa-tRNA isoacceptors. Differential reactivities with near-cognate aa-tRNA are marked by asterisks. Note that for this particular reactivity survey the formylation of fMet was incomplete, and as a result residual Met is observed. This does not affect the analysis because of differences in migration on the TLC between fMet and Met as well as the corresponding dipeptides. A schematic of the initiation complex with fMet-tRNAfMet occupying the P site and the Glu GAA codon occupying the A siteis shown above the scans.

Although the end point of the dipeptide survey reactivities provided some important clues about the effect of the substitutions on the accuracy of peptide-bond formation, these assays fail to provide more quantitative information about the extent to which fidelity is improved. As a result, we resorted to a pre–steady-state kinetics approach to measure the PT rate for the cognate Glu-tRNAGlu ternary complex and the near-cognate Lys-tRNALys and Asp-tRNAAsp ternary complexes. Consistent with our end-point analysis in Fig. 2, the modifications appear to have little effect on the PT rates for the cognate aa-tRNA (Fig. 3A). More specifically, we measure a rate of ∼20⋅s−1 for the O mRNA and ∼15⋅s−1 for the Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate mRNAs. In contrast to the cognate reaction, both substitutions had strong effects on the near-cognate PT rates, with Sp-phosphorothioate having the most drastic effect. In the presence of Lys-tRNALys, PT rates for the O-, Rp-, and Sp-phosphorothioate mRNA-containing complexes were 0.10⋅s−1, 0.0093⋅s−1, and 0.0055⋅s−1, respectively. In addition, the Sp-phosphorothioate complex displayed a drastic end-point defect for which the fraction of fMet that converted to fMet-Lys dipeptide was 27% (Fig. 3B). Conversely, the same reactions with the unmodified and Rp-phosphorothioate went nearly to completion (∼86%). These effects of the phosphorothioate substitutions on near-cognate Lys-tRNALys selection were, by and large, similar to those measured for Asp-tRNAAsp selection. We measured PT rates of 0.056⋅s−1, 0.0089⋅s−1, and 0.017⋅s−1 for the unmodified and Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate complexes, respectively (Fig. 3C). In addition, similar to the Lys-tRNALys reaction, the modifications appear to significantly improve proofreading by the ribosome as evidenced by the reduced end points. The Sp-phosphorothioate complex displayed an even better rejection of the Asp-tRNAAsp, for which we measure an end point of 0.035. In comparison, the end points for the O and Rp-phosphorothioate complexes were 0.33 and 0.11, respectively (Fig. 3C). Collectively these observations suggest that disruption of interactions between the phosphodiester backbone of the mRNA and divalent metals induces a hyperaccurate phenotype.

Fig. 3.

The Sp-phosphorothioate substitution of the kink oxygen results in a severe hyperaccurate phenotype. (A) Representative time courses for PT reactions in the indicated complexes and the cognate Glu-tRNAGlu ternary complex. (B) Representative time course for PT reactions in the indicated complexes and the near-cognate Lys-tRNALys ternary complex. (C) Representative time courses for PT reactions in the indicated complexes and the near-cognate Asp-tRNAAsp ternary complex. (D) Bar graph showing the observed rate of GTP hydrolysis for modified and Rp- and Sp- complexes with the near-cognate Lys-tRNALys ternary complex. Unlike PT reactions, which were all conducted at 37 °C, these reactions were conducted at 20 °C. Shown are the means of three independent time courses; error bars represent the SD from the mean. (E) Representative time courses for RF2-mediated hydrolysis on the indicated complexes. (F) Representative time courses for RF1-mediated hydrolysis reaction on the indicated complexes.

The Accuracy of the Initial Phase of tRNA Selection Is Not Significantly Impacted by the Phosphorothioate Substitutions.

As our peptide-formation assays report on the overall process of tRNA selection, the observed effects of substitutions could, in principle, be the result of defects in the initial selection phase or the proofreading phase of the process. GTP hydrolysis by EF-Tu reports on the GTPase activation of the factor, which in turn reports on the accuracy of the overall initial phase. We measured the rate for GTP hydrolysis for the native and Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate complexes in the presence of the near-cognate Lys-tRNALys ternary complex. In contrast to our observations for peptide-bond formation, the substitution had only a modest effect on the observed rate of GTP hydrolysis (Fig. 3D). For the Rp-modified complex, the observed rate is merely twofold slower relative to the native complex. Similarly, the observed rate for the Sp-modified complex was threefold slower (Fig. 3D). Hence, it appears that the kink structure of the mRNA plays little to no role during the initial phase of the selection process. Instead, given that we measured rates for peptide-bond formation that are almost two orders of magnitude slower under the same conditions, the kink structure likely plays an important role during the proofreading phase. Disruption of this structure appears to reduce the accommodation rates and increase the rejection rates of near-cognate aa-tRNAs.

Phosphorothioate Substitutions Increase the Fidelity of RFs.

Next, we sought to explore the effects of phosphorothioate substitutions on the accuracy of peptide release by RFs. In particular, we were interested in examining whether the kink structure affects protein–mRNA interaction during peptide-release misrecognition of sense codons. The GAA codon displayed in the A site of our complexes is a near-stop for both RF1 and RF2, as both recognize the UAA codon. As a result, we could address the effect of the substitutions on the accuracy of both factors. Although the modifications appear to affect both RF1- and RF2-mediated hydrolysis (Fig. 3 E and F), the extent of these effects was much smaller than those observed for PT, and on average they were two- to threefold slower relative to the native mRNA. We measured rates of hydrolysis for RF2 of 0.012⋅s−1, 0.0045⋅s−1, and 0.0041⋅s−1 for the unmodified and Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate complexes, respectively (Fig. 3E). Similarly, in the presence of RF1, we measured hydrolysis rates of 0.012⋅s−1, 0.0030⋅s−1, and 0.0044⋅s−1 for the unmodified and Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate complexes, respectively (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, and in contrast to tRNA selection, peptide release on the Sp complex was faster (albeit only slightly) than on its Rp counterpart. These observations are consistent with data from our group and others that show the process of RF selection to be different from its tRNA selection counterpart (42, 43). For instance, whereas certain base modifications appear to be detrimental for peptide-bond formation, they have little effect on peptide release (44, 45). Nevertheless, the observation that phosphorothioate substitutions affect peptide release (with little distinction between the two diastereomers) highlights the importance of the mRNA backbone structure during the recognition of A-site ligands regardless of their identity.

The Effects of the Phosphorothioate Substitutions Are Not Dependent on the A-Site Codon Identity.

Our analysis, so far, had focused on one particular mRNA sequence, so our next logical step was to expand our analysis to assess whether the effects of the substitutions we observed are specific or general in nature. Our analysis on the GAA mRNA revealed that both the Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate substitutions appear to severely reduce the observed PT rates for near-cognate aa-tRNAs (Fig. 3). To simplify our approach, in the next set of experiments we chose to synthesize the modified mRNA in one piece and generate mixed complexes with a racemic mixture of the mRNA. The new complexes displayed the CAA Gln codon in the A site. Again we started our analysis by carrying out a survey for all aa-tRNA–isoacceptor reactivities (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). The reactivity profile for these complexes was nearly identical to the one observed for the previous complexes (compare Fig. 3A with SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). The native and phosphorothioate-modified complexes reacted efficiently with the cognate Gln-tRNAGln ternary complex. In contrast, the native complex reacted much better with the near-cognate Asp-tRNAAsp and His-tRNAHis ternary complexes than the modified one (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Furthermore, both RFs 1 and 2 appear to recognize the native complex better than the modified one, for which we observe significant fMet release from fMet-tRNAfMet only for the native complex. Therefore, our survey analysis suggests that effect of the phosphorothioate substitution on A-site ligand binding is general in nature.

To gain a more quantitative understanding of the effects on decoding, we measured the PT rates for the cognate and a near-cognate tRNA as well as the release rate for RF2. Similar to our observations for the previous complexes, the modification had almost no effect on the PT rate for the cognate Gln-tRNAGln complex. We measured rates of 17⋅s−1 and 15⋅s−1 for the unmodified and modified mRNAs, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Also in agreement with our surveying analysis, the modification had a drastic effect on the His-tRNAHis near-cognate reaction. Although the PT rate appears to be unaffected (in fact slightly increased from 0.0037⋅s−1 to 0.0069⋅s−1), the end point of the reaction was dramatically reduced from ∼0.6 to ∼0.05 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). These findings suggest that the modification is likely to increase the rate of aa-tRNA rejection during the proofreading phase of tRNA selection. Finally, and as expected, the modification reduced the rate of RF2-mediated peptide release by almost one order of magnitude (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D). The observation that modification of two independent mRNA sequences has nearly identical effects on peptide-bond formation and peptide release greatly suggests that the effect of the phosphorothioate substitution is independent of the mRNA sequence. This in turn adds more support for the hypothesis that the kinked mRNA structure plays a key role in ribosome function.

Phosphorothioate Modification Reduces Peptide-Bond Formation for a Subset of Cognate aa-tRNAs.

To this point, our analysis revealed that perturbation of the mRNA structure results in aggressive proofreading by the ribosome with little to no effect on cognate tRNA selection. This in turn begs the question as to why the mRNA evolved to adopt this conformation on the ribosome. It is highly likely that the structure plays a role in frame maintenance, as has been suggested by structural biologists (39). However, for our next experiments we were motivated by data on ribosome variants that showed certain hyperaccurate rRNA variants also significantly compromise PT for a subset of cognate aa-tRNAs, in particular those that exploit unusual base pairs at the wobble position (46). For example, to avoid mispairing with the AUG Met codon, the AUA Ile codon in E. coli does not base pair with an anticodon using the typical A:U base pair at the third position. Instead, the corresponding C in the anticodon is modified to lysidine (k2C). Studies by Ortiz-Meoz and Green (46) showed that mutations in helix 69 of the large subunit, while having no effect on most cognate tRNAs, significantly slow the PT rate for tRNAIle(k2C). As a result, we wondered whether the mRNA-kink structure is similarly critical for decoding the AUA codon by Ile-tRNAIle(k2C).

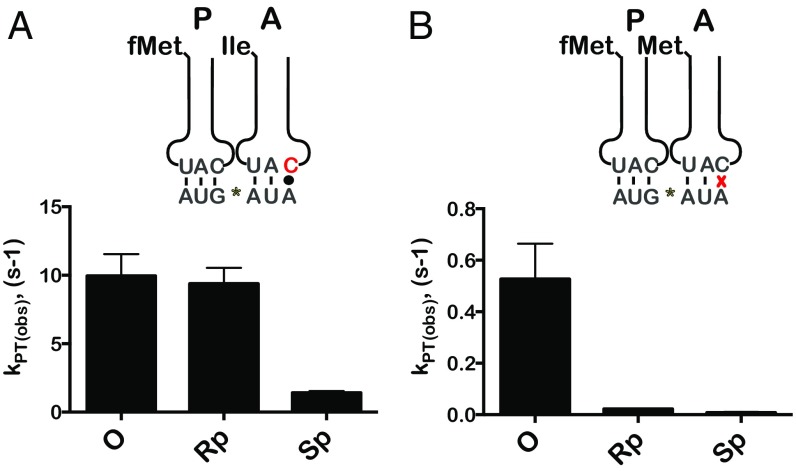

To explore this hypothesis, ribosomes were programmed with three mRNAs: native and Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate–modified mRNAs, all displaying the AUA codon in the A site. In agreement with our earlier observation, the observed PT rate for the Rp-phosphorothioate–programmed complexes with the cognate Ile-tRNAIle was indistinguishable from that for the native complexes (∼10⋅s−1) (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the PT rate for the Sp-modified complex was almost an order of magnitude slower (Fig. 4A). These findings again suggest that the proS oxygen plays a more important role in maintaining the mRNA structure. We note that, similar to our observations for the two previous complexes, the AUA complexes exhibited defects in their reactivity similar to those in near-cognate aa-tRNAs. In the presence of Met-tRNAMet, we measure rates of peptide-bond formation of 0.41⋅s−1, 0.022⋅s−1, and 0.0082⋅s−1 for the native and Rp- and Sp-modified complexes, respectively (Fig. 4B). These observations suggest that the pro-S oxygen, and likely its ability to coordinate magnesium, is critical for decoding under less than ideal conditions.

Fig. 4.

Substitution of the proS oxygen reduces the rate of peptide-bond formation in the presence of atypical tRNA–mRNA interactions. (A) Bar graph showing the PT rate for unmodified and Rp- and Sp- complexes, all displaying the Ile AUA codon in the A site (depicted above), with the cognate Ile-tRNAIle. The corresponding Ile-tRNA harbors the lysidine (k2C) modification at the wobble position. (B) Observed PT rates for the near-cognate Met-tRNAMet in the presence of the indicated complexes. Graphs show the means of three independent time courses; error bars represent the SD from the mean.

Peptide Release Is Not Impacted by Phosphorothioate Modification of the mRNA.

Our analysis thus far has suggested that the kink structure likely is important for decoding a subset of sense codons. As a result, the next logical step was to assess its effects on canonical peptide release. As before, we prepared unmodified and phosphorothioate-mRNA–containing initiation complexes that displayed the UAA stop codon in the A site. Similar to our observations for PT, the rates of peptide release were found to be unaffected by the presence of the phosphorothioate modification at the interface of the P and the A sites of the mRNA. For RF1 we measured rates of 0.35⋅s−1 and 0.49⋅s−1 for the native and modified mRNA, respectively (Fig. 5A). Likewise, for RF2, we measured rates of 0.76⋅s−1 and 0.93⋅s−1 for the same set of mRNAs (Fig. 5B). These observations are in agreement with our model that the kink structure is not important for decoding (sense and missense codons) under optimal conditions.

Fig. 5.

Peptide release is not impacted by phosphorothioate modification at interface of the P-site and A-site codons. (A and B) Representative time courses for peptide release between the indicated initiation complexes (programmed with either a native mRNA or a racemic mixture of phosphorothioate mRNAs) and RF1 and RF2, respectively.

Phosphorothioate Substitutions Between the First and Second Nucleotide of the A-Site Codon also Result in a Hyperaccurate Phenotype.

In addition to the proS oxygen between the P and A site, the kink-stabilizing magnesium ion also appears to be coordinated by the proR oxygen between the first and second position of the A-site codon (39). Consequently, substitution of this oxygen is very likely to perturb the mRNA structure and, in turn, produce a phenotype similar to the one we saw with substitutions at the P/A interface. We used the same strategy as before to generate native as well as modified complexes and assessed the effect of the sulfur substitution on PT rate for cognate and near-cognate aa-tRNAs.

Consistent with earlier observations, both Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate substitutions at the second position of the A site have minimal effects on peptide-bond formation for the cognate aa-tRNA (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the same substitutions significantly reduced the PT rates for the two tested near-cognate ternary complexes, Lys-tRNALys and Asp-tRNAAsp (Fig. 6 B and C). However, whereas the proS oxygen at the P/A interface appears to have a larger effect on decoding near-cognate aa-tRNAs, at this position in the A site the Rp-phosphorothioate substitution had a much more pronounced effect on the selection of these very same aa-tRNAs. In particular, PT rates for lys-tRNAlys were 0.080⋅s−1, 0.0039⋅s−1, and 0.011⋅s−1 for the native and Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate complexes, respectively. Similarly, PT rates for Asp-tRNAAsp were 0.035⋅s−1, 0.0049⋅s−1, and 0.0050⋅s−1 for the native and Rp- and Sp-phosphorothioate complexes, respectively. Furthermore, the end points for the same reactions were 0.51, 0.11, and 0.21, respectively, suggesting that the modification also increases the rejection rate for the near-cognate aa-tRNAs during the proofreading phase of the selection. Interestingly, at this position, the substitution does not appear to affect peptide release by RF1 (Fig. 6D) and appears to affect that by RF2 only slightly (Fig. 6E). These observations again highlight the distinction between tRNA and RF selections, with the latter being more robust to perturbations. Nevertheless, taken together, our data suggest that coordination of the magnesium ion by the phosphodiester backbone of the mRNA, and likely the resulting mRNA structure, plays a significant role during decoding.

Fig. 6.

Phosphorothioate modification at the second position of the A-site codon results in a hyperaccurate phenotype. (A) Representative time courses of peptide-bond formation between the depicted unmodified or modified complexes with the cognate Glu-tRNAGlu. The phosphorothioate modification is between the G and A of the A-site GAA codon (as shown above). (B and C) Time courses of PT reactions with the near-cognate Lys-tRNALys (B) and Asp-tRNAAsp (C) ternary complexes, respectively. (D and E) Time courses for RF1- and RF2-mediated hydrolysis reactions, respectively.

Phosphorothioate Substitutions Between the Second and Third Nucleotide of the A-Site Codon Have Little Effect on the Accuracy of tRNA Selection.

Unlike that of the P/A interface and the first position of A-site codon, the phosphate of the second position of the A-site codon does not appear to coordinate a divalent metal (Fig. 1A). Therefore, phosphorothioate substitution at this position should serve as a nice control for effects resulting from mere sulfur introduction into the backbone of the mRNA versus magnesium structural stabilization effects. We used the same GAA codon-containing mRNA but introduced the sulfur substitution between the last two nucleotides (GA-Sp-A) to generate modified initiation complexes. As expected, the substitution had no effect on the observed rate of peptide-bond formation by the cognate Glu-tRNAGlu ternary complex (Fig. 7A). In the presence of the near-cognate Lys-tRNALys ternary complex, we observed a modest threefold decrease for the modified complex (Fig. 7B). In comparison, we saw a 20-fold decrease in the observed rate for the same mRNA when it was modified at the first position (Fig. 6B), which was also accompanied by a fourfold reduction in the end point of the reaction. These observations suggest that while the introduction of sulfur on its own has some effects on the accuracy of peptide-bond formation, magnesium coordination by the nonbridging oxygen atoms of the mRNA backbone, and hence its structure, plays a far more important role in decoding accuracy.

Fig. 7.

Phosphorothioate substitution between the second and third nucleotide of the A-site codon does not significantly impact PT. (A and B) Representative time courses for PT between the indicated initiation complexes and the cognate Glu-tRNAGlu (A) and near-cognate Lys-tRNALys (B). The phosphorothioate modification is between the second and third nucleotide of the A-site codon (as shown above).

The Presence of a Deoxyribose Sugar Between the A- and P-Site Codons Results in a Hyperaccurate Phenotype.

Thus far, our studies focused on the role of the phosphodiester backbone on the accuracy of tRNA selection and suggested an important role for its structure during this process. As a logical next step, we sought to examine the role of the mRNA ribose backbone in the accuracy of decoding. Initial structural studies of the small subunit highlighted the potential role for the chemical structure of the ribose in decoding. These studies suggested that the A-site 2′-OH groups are important for distinguishing between cognate and near-cognate tRNAs (31, 32). In particular, rRNA residues G530, A1492, and A1493 were shown to monitor the minor groove of the cognate codon–anticodon helix by forming hydrogen bonds with the 2′-OH groups. However, recent structural studies from a different group suggested that the hydrogen bonding was identical for both cognate and near-cognate codons (38) and that accuracy originates from energetic penalties associated with base-pair mismatches being forced to adopt a Watson–Crick base-pair geometry. Previous biochemical studies by Simpson and colleagues (37) explicitly addressed the role of the 2′-OH groups of the A site in decoding. Interestingly, single substitution of any of the 2′-OH groups by a deoxy only marginally affected peptide-bond formation. Multiple deoxy substitutions, on the other hand, severely inhibited tRNA selection parameters. In contrast, 2′-fluoro substitutions of all three hydroxyl groups of the A site had little to no effect on tRNA selection. These findings suggested that hydrogen bonds with the ribose backbone are not important for decoding; instead, shape complementarity of the bases and their partners appears to be paramount. We note that these studies looked at the role of the 2′-OH groups in the accuracy of the decoding process through competition assays. These assays suggested that individual substitutions have no effect on fidelity. However, their effect on peptide-bond formation in the presence of near-cognate aa-tRNAs was not directly measured.

Motivated by these earlier findings, we next explored the role of the 2′-OH groups of the ribose backbone in discriminating against near-cognate tRNAs. As in the phosphorothioate assays, we prepared initiation complexes that displayed the Glu GAA codon in the A site. In addition to the native complex, we generated four more complexes that harbored one deoxy substitution at the third position of the P-site codon or at the first, second, or third position of the A-site codon. As had been seen earlier, these substitutions had a negligible effect on the rate of peptide-bond formation in the presence of the cognate aa-tRNA (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the substitutions had drastic effects on PT in the presence of the near-cognate Lys-tRNALys, with the substitutions of the A-site codon having the most profound effect (Fig. 8B). More specifically, introducing the deoxy modification to the third position of the P-site codon resulted in a 10-fold decrease in the observed rate of PT, with no appreciable effect on the end point (Fig. 8B). In contrast, although the observed rates for A-site–substituted complexes do not vary much from those of the unmodified complex, the end points for these reactions were severely diminished (1–2% of the initiation complexes reacted with the ternary complex) (Fig. 8B). Hence, substitution of the hydroxyl groups of the A-site codon appears to result in aggressive proofreading by the ribosome.

Fig. 8.

Deoxyribose substitutions in the A-site codon result in a severe hyperaccurate phenotype. (A) Representative time courses for PT reactions between the initiation complexes programmed with the indicated native and deoxyribose-modified mRNAs and the cognate Glu-tRNAGlu ternary complex. (B) Representative time courses for PT reactions between the indicated complexes and the near-cognate Lys-tRNALys ternary complex. (C) Representative time course for PT between complexes displaying the native AUA codon or the deoxy-modified one at the third position of the codon (AUdA) and the cognate Ile-tRNAIle ternary complex. The corresponding Ile-tRNA harbors the lysidine (k2C) modification at the wobble position.

These findings suggested that, similar to our findings with the phosphorothioate substitutions, the 2′-OH groups might be important for decoding when the codon–anticodon interaction is compromised. To provide further support for these ideas, we again resorted to the unusual decoding event of the AUA codon. In addition to the native complex, which displayed the unmodified AUA codon in the A site, we also generated a complex that displayed a deoxy-modified AUA codon at the third position (AUdA). As expected, the native complex reacted efficiently and rapidly with the cognate Ile-tRNAIle ternary complex (Fig. 8C) with an observed rate of 13⋅s−1. In contrast, the deoxy-modified complex reacted very slowly with the same ternary complex and did not go to completion even after 10 min of incubation; we measured an observed rate of 0.013⋅s−1 and an end point of 24%. Similar to our observations for the phosphorothioate substitutions, these results support a model for decoding in which the hydroxyl groups are dispensable under optimal base-pairing conditions but become critical when base pairing is compromised.

Discussion

Decades of biochemical and structural studies on translation have shown almost every component of the translational machinery, including the ribosomal RNA and proteins, tRNAs, and translation factors, to be important for faithful and rapid decoding (11, 29). In contrast, the role of the mRNA substrate itself during the process has been largely overlooked. Beyond its primary role in interrogating the incoming tRNA to ensure that matched codon–anticodon interactions are maintained, the mRNA is arguably perceived as a mere onlooker during elongation. It is worth noting that the tRNA substrate was also viewed similarly until structural and biochemical data provided compelling evidence to the contrary (28, 36). For instance, the tRNA is very dynamic during the selection process, adopting distinct conformations as it moves into the A site and eventually participating in PT (47, 48). Perturbance of this conformational flexibility has significant consequences on the fidelity of protein synthesis, allowing tRNAs to read the incorrect codon (49). In addition to its role in decoding, the tRNA plays an important role in the chemistry of peptide-bond formation and peptide release (50–54). The hydroxyl group of the terminal ribose (A76) of the tRNA and its ability to form a hydrogen-bonding network is important for PT (54) and appears to be absolutely required for peptide release (55, 56). Similar to the findings of studies on the functional importance of the tRNA structure, it is highly likely that the mRNA structure plays an extensive role in many aspects of protein synthesis.

Early structural studies of the decoding process revealed a central role for the ribose backbone of the mRNA in maintaining codon–anticodon interactions (31). These include A-minor interactions between the mRNA and decoding center rRNA nucleotides. In addition to interacting with O2 and N4 of the respective purine and pyrimidine bases of the codon/anticodon, the rRNA residues also hydrogen bond with the 2′-OH groups of the mRNA (31). Disruption of these interactions by replacing the ribose groups with 2′-deoxy ribose or 2′-fluoro results, as expected, in increased dissociation of the A-site tRNAs (57). However, these substitutions also result in increased translocation rates (57), suggesting that disruption of the interactions between the mRNA and tRNAs is required to remodel the mRNA during translocation. In contrast to their role in translocation, the 2′-OH groups of the A-site codon appear to be dispensable for tRNA selection (37); instead, shape complementarity appears to be the driving force for decoding. While these limited studies have highlighted the importance of the ribose backbone of mRNA during translation, the importance of the phosphodiester backbone has not been explored. In functional RNAs, the phosphodiester backbone plays an important role in coordinating divalent metals (58), which are important for maintaining the overall structure of the molecule; in certain cases the metal is directly responsible for the function of the RNA (59, 60). In the case of the ribosome, atomic-resolution structures have revealed a number of locations where metals appear to play an important role (39). However, the contribution of most of these sites to the function of the ribosome has not been directly tested. Naturally, the main limitation to carrying out such studies is the difficulty of conducting atomic mutagenesis on the rRNA and, in particular, substitutions of nonbridging oxygen atoms to interfere with metal binding. In contrast to the ribosome, these types of phosphorothioate substitutions approaches have been instrumental in working out mechanisms of ribozymes (61).

In addition to rRNA, structural studies have shown the mRNA backbone to be directly involved in coordinating at least one divalent metal at the interface of the P/A sites of the small subunit (38, 39). More important, the metal appears to play a critical role in maintaining an unusual structure of the mRNA characterized by a kink. This in turn allows rRNA nucleobases of the small subunit to sandwich themselves (through base stacking) between the P and the A sites and in the process divide the two sites (38, 39). These initial studies speculated that this structure is important for preventing slippage and hence frameshifting during translocation (39). In contrast to its supposed role in frame maintenance, the role of the kink in decoding has not been considered previously. By disrupting the interaction between the mRNA and the divalent metal (and very possibly the kink structure) through phosphorothioate substitutions, we were able to show that the structure is likely important for uniform decoding. In particular, whereas the substitutions appear to have little to no effect on PT for cognate tRNAs that utilize typical Watson–Crick as well as G–U wobble base pairs, they dramatically reduced PT for an aa-tRNA that uses atypical base pairing at the third position. Substitution of the proS oxygen (one of the atoms involved in coordinating the crucial divalent metal) at the kink reduced the PT rate for Ile-tRNAIle(k2C) by more than fivefold (Fig. 4A). Consistent with its role in boosting tRNA selection under compromised conditions, altering the kink structure also resulted in a severe hyperaccurate phenotype (Figs. 3 and 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). As a case in point, the rate of the peptide bond reaction and the end point for the near-cognate Lys-tRNALys on the Sp-GAA codon is ∼20-fold slower and approximately fourfold lower than that for the unmodified mRNA (Fig. 3 B and C). We note that these observed effects of the phosphorothioate substitutions on the tRNA selection, through which the effective accuracy is improved by almost two orders of magnitude, are much more dramatic than those observed in hyperaccurate-variant ribosomes. Restrictive mutations in the ribosomal protein S12, for instance, have been documented to improve accuracy by less than 10-fold (62). Similarly, mutations in H69 have been shown to improve accuracy by only threefold (46). These observations argue that, beyond its requirement to base pair with the tRNA, the mRNA structure is at least equally critical for tRNA selection as the rRNA and ribosomal proteins.

Arguably, one of the key questions that came out of this study is how the kink structure might affect the interaction between the mRNA and the incoming tRNA. While our data alone do not answer this question, one could take advantage of the available structural and biochemical information to come up with scenarios to explain our findings. Disruption of the kink structure appears to affect the later steps of tRNA selection more severely than the early steps (Fig. 3). In particular, in the presence of the Sp-phosphorothioate modification, PT reactions with near-cognates exhibited drastic end-point defects (Fig. 3 B and C) but a modest decrease in the observed rate of GTP hydrolysis (Fig. 3D). Hence, interfering with magnesium binding at the P/A interface appears to increase the rate of near-cognate tRNA rejection. It is plausible that the kink structure serves to rigidify the mRNA in the A site; as a result, the mRNA is more dynamic in its absence. Consequently, the dissociation rate of the tRNA is likely to increase during the proofreading phase. For typical cognate aa-tRNAs, the proceeding step of accommodation is so rapid that the increase in the dissociation rate is not realized to an extent that would affect the overall selection process. For near-cognate aa-tRNAs, accommodation is much slower, and, as a result, the effects of the kink disruption on codon recognition are felt, reducing the overall rate of peptide-bond formation. These ideas are corroborated by the observations that disruption of potential hydrogen bonds with the 2′-OH of the A-site codon has a modest effect on cognate tRNA selection but drastically diminishes peptide-bond formation in the presence of near-cognate aa-tRNAs (Fig. 8).

In an alternative scenario, the kink structure could play a role relaying signals between the P and the A sites of the ribosome. This idea is motivated by earlier studies by our group showing that mismatches in the P site severely compromise the fidelity of the next bout of tRNA selection (63, 64). These earlier findings as well as the observations we report here are consistent with a model in which the extended mRNA–tRNA interaction is important for decoding. Notwithstanding, whatever the mechanism by which the kink affects decoding may be, our findings provide some previously unappreciated insights into the role of the substrate mRNA in ensuring that protein synthesis proceeds uniformly. The observation that a mere atomic substitution of one of the nonbridging oxygen atoms can drastically modify tRNA selection parameters argues that decoding is an intricate process that evolved to take advantage of all available interactions for optimal gene expression. In addition to this role in tRNA selection, the mRNA structure is highly likely to be important for frame maintenance. Indeed, mutations and perturbations even farther from the A site in the E site have been shown to increase frameshifting (65). It will be exciting to directly probe the role of the kink in translocation and to explore whether phosphorothioate substitutions affect frameshifting.

Experimental Procedures

Materials and Reagents.

Unmodified mRNAs were synthesized using in vitro runoff transcription by T7 RNA polymerase (66). dsDNA templates were amplified from single-stranded oligonucleotides that were purchased from IDT. The final DNA templates had the following sequences:

AUG-GAA (Met-Glu):

TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTAACTTTAGAAGGAGGTATACTATGGAATAACTCGCATGCCCACTTGTCGATCACCGCCCTTGATTTGCCCTTCTGT

AUG-CAA (Met-Gln):

TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTAACTTTAGAAGGAGGTATACTATGCAATAACTCGCATGCCCACTTGTCGATCACCGCCCTTGATTTGCCCTTCTGT

AUG-AUA (Met-Ile):

TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTAACTTTAGAAGGAGGTATACTATGATATAACTCGCATGCCCACTTGTCGATCACCGCCCTTGATTTGCCCTTCTGT

The T7 promoter is italicized, the Shine–Dalgarno sequence is underlined, and the imitation codon is in bold.

AUG-sCAA (Met-Gln)–modified mRNA with the sequence AAGGAGGTAAAAAAAATGsCAAAAGTAA (“s” indicates the site of the phosphorothioate modification) was purchased from Dharmacon. AUG-sGAA, AUG-sAUA, and AUG-GsAA phosphorothioate-modified mRNAs were generated from two chemically synthetized ribo-oligonucleotides purchased from IDT. The upstream sequence of AAUAAGGAGGUAUACU was common to all of them. The downstream oligonucleotides had the following sequences: AUGsGAAUUU, AUGsAUAUUU, and AUGGsAAUUU, respectively. Before generating the full-length mRNAs, the modified oligonucleotides were separated into the Rp and Sp diastereoisomers using reverse-phase chromatography as described earlier (67). In particular, 10 nmol of RNA was injected into an Agilent 1100 HPLC system equipped with a C18 column (Zorbax ODS, 5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm). The following conditions were used for the purification: The column was equilibrated with 100 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7) containing 3% acetonitrile; 5 min following injection, the acetonitrile concentration was linearly increased to 13% over a 15-min period and was kept there for an additional 5 min. During the purification, the column was maintained at 45 °C. The purified RNA was dried using a SpeedVac concentrator (Savant) at ambient temperature overnight. The purified oligonucleotides were resuspended in water and then were phosphorylated using polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) in the presence of ATP. Before the ligation reaction was initiated, the upstream and the phosphorylated purified modified oligonucleotides were annealed to a DNA splint with final concentrations of 13 μM upstream RNA sequence, 10 μM modified phosphorylated oligonucleotide, and 11 μM DNA splint. The DNA splints had the following sequences: AAATTCCATAGTATACCT for the AUG-sGAA and AUG-GsAA mRNAs and AAATAT CATAGTATACCT for the AUG-sAUA mRNA. Ligation was carried out using T4 RNA ligase 2 (New England Biolabs) and incubation at 37 °C for 2 h. The ligated products were purified away from the substrate RNA and DNA splint using denaturing PAGE.

Tight-coupled 70S ribosomes were purified using a double-pelleting strategy as described (68). Briefly, clarified lysate was centrifuged at 107,100 × g for 16 h over a sucrose cushion at 4 °C; the ribosome pellet was resuspended, and the centrifugation step was repeated. Ribosomes were stored in Polymix buffer (69) [95 mM KCl, 5 mM NH4Cl, 5 mM Mg(OAc)2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 8 mM putrescine, 1 mM spermidine, 5 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5), 1 mM DTT], aliquoted, flash-frozen, and stored at −80 °C. His-tagged IF1, IF3 (45), and IF2 (70) were purified over Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin as described earlier (45). Purification of the His-tagged 20-aa tRNA synthetases RF1 and RF2 was carried out as described in ref. 70. EF-Tu and EF-G were also purified over Ni-NTA resin; following purification the His tag was removed using Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease (71). E. coli tRNAfMet, RNAMet, RNAGlu, RNALys, RNAArg, RNAVal, RNAPhe, and RNATyr were purchased from ChemBlock.

tRNA Aminoacylation.

[35S]-fMet-tRNAfMet was prepared as described (72) using Met-tRNA synthetase and methionyl-tRNA formyltransferase in the presence of [35S]-Met (Perkin Elmer) and a 10-formyltetrahydrofolate formyl donor at 37 °C. Purified tRNAs were aminoacylated as described (41) by incubation in the presence of the appropriate tRNA synthetase, the corresponding amino acid, and ATP. All other tRNAs were charged by incubating E. coli total tRNA (Roche) with the applicable tRNA synthetase and the equivalent amino acid in the presence of ATP.

Ribosome Complex Formation.

Initiation complexes were generated as described previously (45) by mixing 2 µM 70S ribosomes with 3 µM IF1, IF2, IF3, [35S]-fMet-tRNAfMet, 6 µM mRNA, and 2 mM GTP in Polymix buffer. Following incubation at 37 °C for 2 min, the mixture was placed on ice before MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 10 mM. The complex was purified away from IFs and unbound tRNA and mRNA through centrifugation over a sucrose cushion [1.1 M sucrose, 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 500 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA] at 223,424 × g in an MLA-130 rotor (Beckman) for 2 h at 4 °C. The purified pelleted complexes were resuspended in Polymix buffer (using the original volume). Small aliquots were taken before and after centrifugation for scintillation counting to estimate complex recovery and concentration.

Dipeptide Formation and Release Assays.

Ternary complexes were generated by first incubating 30 μM EF-Tu with 2 mM GTP to exchange bound GDP at 37 °C for 15 min before adding the appropriate aa-tRNA to a final concentration of 4 µM. The mixture was further incubated for an additional 15 min. Peptide-bond formation was initiated by mixing equal volumes of initiation complex and ternary complex at 37 °C. For fast reactions, the mixing was done on an RQF-3 quench flow apparatus (KinTek) at 37 °C. The reactions were quenched by the addition of KOH to a final concentration of 0.5 M. Dipeptides were resolved from unreacted fMet using cellulose TLC plates electrophoresed in a PyrAC buffer (3.48 M acetic acid, 62 mM pyridine) and Stoddard’s solvent at 1,200 V (40). The TLC plates were dried and exposed to phosphoscreens before imaging on a Bio-Rad personal imager phosphorimager. The fractional reactivity corresponding to the dipeptide was quantified as a function of time using Bio-Rad Quantity One software. The resulting data were fit to a single-exponential function using GraphPad prism software. All reactions were conducted at least in duplicate.

Peptide release was carried out by mixing 2 µM initiation complex with 10 µM RF1 and RF2 in Polymix buffer at 37 °C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of formic acid to a final concentration of 5% or EDTA to a final concentration of 20 mM. Released fMet was resolved from fMet-tRNAfMet using electrophoretic TLCs as described above.

Kinetics of GTP Hydrolysis.

Initiation complexes were generated as above except that fMet-tRNAfMet was nonradioactive. Ternary complexes were prepared by incubating 10 μM unlabeled GTP, 20 μCi (6,000 Ci/mmol) [γ-32P]-GTP, 20 μM EF-Tu, and 10 μM Lys-tRNALys in Polymix buffer at 4 °C for 10 min. The ternary complexes were layered over P-30 gel-filtration spin columns (Bio-Rad) equilibrated with Polymix and were centrifuged for 1 min at 1,000 × g at room temperature. The flow-through was layered over a second spin column, and the spin was repeated. The final ternary complex was diluted threefold in the process. To measure rates, equal volumes of ternary complexes and initiation complexes were combined at 20 °C, and reactions were quenched with 20% formic acid (final concentration). Inorganic phosphate was resolved from unreacted GTP using PEI-cellulose TLC plates (Sigma) and 0.5 M KH2PO4 (pH 3.5) as a mobile phase and were visualized via phosphorimaging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bob Kranz and Allen Buskirk for commenting on earlier versions of the manuscript and members of the H.S.Z. laboratory for useful discussions. This work was supported by NIH Grant R01GM112641 (to H.S.Z.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1721431115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rosenberger RF, Foskett G. An estimate of the frequency of in vivo transcriptional errors at a nonsense codon in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;183:561–563. doi: 10.1007/BF00268784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edelmann P, Gallant J. Mistranslation in E. coli. Cell. 1977;10:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouadloun F, Donner D, Kurland CG. Codon-specific missense errors in vivo. EMBO J. 1983;2:1351–1356. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer EB, Farabaugh PJ. The frequency of translational misreading errors in E. coli is largely determined by tRNA competition. RNA. 2007;13:87–96. doi: 10.1261/rna.294907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson RC. EFTu provides an internal kinetic standard for translational accuracy. Trends Biochem Sci. 1988;13:91–93. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(88)90047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopfield JJ. Kinetic proofreading: A new mechanism for reducing errors in biosynthetic processes requiring high specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:4135–4139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ninio J. Kinetic amplification of enzyme discrimination. Biochimie. 1975;57:587–595. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(75)80139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pape T, Wintermeyer W, Rodnina M. Induced fit in initial selection and proofreading of aminoacyl-tRNA on the ribosome. EMBO J. 1999;18:3800–3807. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson M, Bouakaz E, Lovmar M, Ehrenberg M. The kinetics of ribosomal peptidyl transfer revisited. Mol Cell. 2008;30:589–598. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gromadski KB, Rodnina MV. Kinetic determinants of high-fidelity tRNA discrimination on the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2004;13:191–200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaher HS, Green R. Fidelity at the molecular level: Lessons from protein synthesis. Cell. 2009;136:746–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crick FH. On the genetic code. Science. 1963;139:461–464. doi: 10.1126/science.139.3554.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLaughlin CS, Dondon J, Grunberg-Manago M, Michelson AM, Saunders G. Stability of the messenger RNA-sRNA-ribosome complex. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1966;31:601–610. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1966.031.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorini L, Jacoby GA, Breckenridge L. Ribosomal ambiguity. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1966;31:657–664. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1966.031.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosset R, Gorini L. A ribosomal ambiguity mutation. J Mol Biol. 1969;39:95–112. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmermann RA, Garvin RT, Gorini L. Alteration of a 30S ribosomal protein accompanying the ram mutation in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2263–2267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birge EA, Kurland CG. Reversion of a streptomycin-dependent strain of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1970;109:356–369. doi: 10.1007/BF00267704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brownstein BL, Lewandowski LJ. A mutation suppressing streptomycin dependence. I. An effect on ribosome function. J Mol Biol. 1967;25:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stöffler G, Deusser E, Wittmann HG, Apirion D. Ribosomal proteins. XIX. Altered S5 ribosomal protein in an Escherichia coli revertant from strptomycin dependence to independence. Mol Gen Genet. 1971;111:334–341. doi: 10.1007/BF00569785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorini L, Kataja E. Phenotypic repair by streptomycin of defective genotypes in E. coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1964;51:487–493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.51.3.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozaki M, Mizushima S, Nomura M. Identification and functional characterization of the protein controlled by the streptomycin-resistant locus in E. coli. Nature. 1969;222:333–339. doi: 10.1038/222333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connor M, Dahlberg AE. The involvement of two distinct regions of 23 S ribosomal RNA in tRNA selection. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:838–847. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor M, Thomas CL, Zimmermann RA, Dahlberg AE. Decoding fidelity at the ribosomal A and P sites: Influence of mutations in three different regions of the decoding domain in 16S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1185–1193. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClory SP, Leisring JM, Qin D, Fredrick K. Missense suppressor mutations in 16S rRNA reveal the importance of helices h8 and h14 in aminoacyl-tRNA selection. RNA. 2010;16:1925–1934. doi: 10.1261/rna.2228510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carr-Schmid A, Durko N, Cavallius J, Merrick WC, Kinzy TG. Mutations in a GTP-binding motif of eukaryotic elongation factor 1A reduce both translational fidelity and the requirement for nucleotide exchange. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30297–30302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito K, Uno M, Nakamura Y. Single amino acid substitution in prokaryote polypeptide release factor 2 permits it to terminate translation at all three stop codons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8165–8169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirsh D. Tryptophan transfer RNA as the UGA suppressor. J Mol Biol. 1971;58:439–458. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cochella L, Green R. An active role for tRNA in decoding beyond codon:anticodon pairing. Science. 2005;308:1178–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.1111408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voorhees RM, Ramakrishnan V. Structural basis of the translational elongation cycle. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:203–236. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-113009-092313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmeing TM, Ramakrishnan V. What recent ribosome structures have revealed about the mechanism of translation. Nature. 2009;461:1234–1242. doi: 10.1038/nature08403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogle JM, et al. Recognition of cognate transfer RNA by the 30S ribosomal subunit. Science. 2001;292:897–902. doi: 10.1126/science.1060612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogle JM, Murphy FV, Tarry MJ, Ramakrishnan V. Selection of tRNA by the ribosome requires a transition from an open to a closed form. Cell. 2002;111:721–732. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loveland AB, Demo G, Grigorieff N, Korostelev AA. Ensemble cryo-EM elucidates the mechanism of translation fidelity. Nature. 2017;546:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature22397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmeing TM, et al. The crystal structure of the ribosome bound to EF-Tu and aminoacyl-tRNA. Science. 2009;326:688–694. doi: 10.1126/science.1179700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voorhees RM, Schmeing TM, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V. The mechanism for activation of GTP hydrolysis on the ribosome. Science. 2010;330:835–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1194460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmeing TM, Voorhees RM, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V. How mutations in tRNA distant from the anticodon affect the fidelity of decoding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:432–436. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khade PK, Shi X, Joseph S. Steric complementarity in the decoding center is important for tRNA selection by the ribosome. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:3778–3789. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demeshkina N, Jenner L, Westhof E, Yusupov M, Yusupova G. A new understanding of the decoding principle on the ribosome. Nature. 2012;484:256–259. doi: 10.1038/nature10913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selmer M, et al. Structure of the 70S ribosome complexed with mRNA and tRNA. Science. 2006;313:1935–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.1131127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Youngman EM, Brunelle JL, Kochaniak AB, Green R. The active site of the ribosome is composed of two layers of conserved nucleotides with distinct roles in peptide bond formation and peptide release. Cell. 2004;117:589–599. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierson WE, et al. Uniformity of peptide release is maintained by methylation of release factors. Cell Rep. 2016;17:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freistroffer DV, Kwiatkowski M, Buckingham RH, Ehrenberg M. The accuracy of codon recognition by polypeptide release factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2046–2051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030541097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petropoulos AD, McDonald ME, Green R, Zaher HS. Distinct roles for release factor 1 and release factor 2 in translational quality control. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:17589–17596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.564989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hudson BH, Zaher HS. O6-methylguanosine leads to position-dependent effects on ribosome speed and fidelity. RNA. 2015;21:1648–1659. doi: 10.1261/rna.052464.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simms CL, Hudson BH, Mosior JW, Rangwala AS, Zaher HS. An active role for the ribosome in determining the fate of oxidized mRNA. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1256–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ortiz-Meoz RF, Green R. Helix 69 is key for uniformity during substrate selection on the ribosome. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25604–25610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.256255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agirrezabala X, et al. Visualization of the hybrid state of tRNA binding promoted by spontaneous ratcheting of the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2008;32:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agirrezabala X, et al. Structural insights into cognate versus near-cognate discrimination during decoding. EMBO J. 2011;30:1497–1507. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ortiz-Meoz RF, Green R. Functional elucidation of a key contact between tRNA and the large ribosomal subunit rRNA during decoding. RNA. 2010;16:2002–2013. doi: 10.1261/rna.2232710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmeing TM, Huang KS, Kitchen DE, Strobel SA, Steitz TA. Structural insights into the roles of water and the 2′ hydroxyl of the P site tRNA in the peptidyl transferase reaction. Mol Cell. 2005;20:437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trobro S, Aqvist J. Mechanism of peptide bond synthesis on the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12395–12400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504043102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dorner S, Panuschka C, Schmid W, Barta A. Mononucleotide derivatives as ribosomal P-site substrates reveal an important contribution of the 2′-OH to activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6536–6542. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dorner S, Polacek N, Schulmeister U, Panuschka C, Barta A. Molecular aspects of the ribosomal peptidyl transferase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:1131–1136. doi: 10.1042/bst0301131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaher HS, Shaw JJ, Strobel SA, Green R. The 2′-OH group of the peptidyl-tRNA stabilizes an active conformation of the ribosomal PTC. EMBO J. 2011;30:2445–2453. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw JJ, Trobro S, He SL, Åqvist J, Green R. A role for the 2′ OH of peptidyl-tRNA substrate in peptide release on the ribosome revealed through RF-mediated rescue. Chem Biol. 2012;19:983–993. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brunelle JL, Shaw JJ, Youngman EM, Green R. Peptide release on the ribosome depends critically on the 2′ OH of the peptidyl-tRNA substrate. RNA. 2008;14:1526–1531. doi: 10.1261/rna.1057908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khade PK, Joseph S. Messenger RNA interactions in the decoding center control the rate of translocation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1300–1302. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Draper DE, Grilley D, Soto AM. Ions and RNA folding. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:221–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bowman JC, Lenz TK, Hud NV, Williams LD. Cations in charge: Magnesium ions in RNA folding and catalysis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2012;22:262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fedor MJ, Williamson JR. The catalytic diversity of RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:399–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frederiksen JK, Piccirilli JA. Identification of catalytic metal ion ligands in ribozymes. Methods. 2009;49:148–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zaher HS, Green R. Hyperaccurate and error-prone ribosomes exploit distinct mechanisms during tRNA selection. Mol Cell. 2010;39:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zaher HS, Green R. Quality control by the ribosome following peptide bond formation. Nature. 2009;457:161–166. doi: 10.1038/nature07582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zaher HS, Green R. Kinetic basis for global loss of fidelity arising from mismatches in the P-site codon:anticodon helix. RNA. 2010;16:1980–1989. doi: 10.1261/rna.2241810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Devaraj A, Shoji S, Holbrook ED, Fredrick K. A role for the 30S subunit E site in maintenance of the translational reading frame. RNA. 2009;15:255–265. doi: 10.1261/rna.1320109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zaher HS, Unrau PJ. T7 RNA polymerase mediates fast promoter-independent extension of unstable nucleic acid complexes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7873–7880. doi: 10.1021/bi0497300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frederiksen JK, Piccirilli JA. Separation of RNA phosphorothioate oligonucleotides by HPLC. Methods Enzymol. 2009;468:289–309. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)68014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cochella L, Brunelle JL, Green R. Mutational analysis reveals two independent molecular requirements during transfer RNA selection on the ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:30–36. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jelenc PC, Kurland CG. Nucleoside triphosphate regeneration decreases the frequency of translation errors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:3174–3178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shimizu Y, et al. Cell-free translation reconstituted with purified components. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:751–755. doi: 10.1038/90802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blanchard SC, Gonzalez RL, Kim HD, Chu S, Puglisi JD. tRNA selection and kinetic proofreading in translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1008–1014. doi: 10.1038/nsmb831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Walker SE, Fredrick K. Preparation and evaluation of acylated tRNAs. Methods. 2008;44:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.