Abstract

Objectives:

To understand trends in health care use among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), this study compared trends in hospitalization rates, comorbidities, and hospital death rates of hospitalized PLWHA with the overall hospitalized population in Illinois during 2008-2014.

Methods:

This study identified principal hospitalizations (the principal discharge diagnosis coded with an HIV-related billing code) and secondary HIV hospitalizations (a non-principal discharge diagnosis coded with an HIV-related billing code) from 2008-2014 Illinois hospital discharge data. Hospitalization rates among PLWHA were calculated using prevalence data from the Illinois Electronic HIV/AIDS Registry; US Census population estimates were used to calculate overall Illinois hospitalization rates. Joinpoint regression analysis was used to assess trends overall and among demographic subgroups. Comorbidities and discharge status for all hospitalizations were identified.

Results:

In 2014, the hospitalization rate was 2.2 times higher among PLWHA than among the overall Illinois hospitalized population. From 2008 to 2014, principal HIV hospitalization rates per 1000 PLWHA decreased by 48% (from 71 to 37) and secondary HIV hospitalization rates declined by 26% (from 296 to 218). The decline in the principal HIV hospitalization rate was steepest from 2008 to 2011 (annual percentage change = –16.0%; P = .003). Mood disorders, substance-related diagnoses, and schizophrenia accounted for 18% to 22% of principal hospitalizations among PLWHA compared with 7% to 8% of overall Illinois hospitalizations. Hepatitis as a comorbidity was more common among hospitalized PLWHA (18%-22%) than among the overall Illinois hospitalized population (1.4%-1.5%). Hospitalized PLWHA were 3 times more likely than the overall Illinois hospitalized population to die while hospitalized.

Conclusions:

HIV hospitalizations are largely preventable with appropriate treatment and adherence. Additional efforts to improve retention in HIV care that address comorbidities of PLWHA are needed.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, hospitalization, comorbidities, disparities, mental health

In the United States and Illinois, the past 2 decades have resulted in substantial progress in addressing the HIV epidemic. The number of people newly diagnosed with HIV in the United States has decreased, and people diagnosed with HIV who are on treatment are living longer compared with 2 decades ago, with a lower proportion of those with HIV infection progressing to AIDS.1 In Illinois, from 2008 to 2014, the annual HIV incidence rate decreased from 15 to 13 new HIV diagnoses per 100 000 population, whereas the prevalence rate increased from 231 to 287 people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) per 100 000 population.2

Despite this progress, untreated PLWHA continue to have opportunistic infections and other consequences of living with uncontrolled disease.3 For PLWHA who are on treatment, long-term antiretroviral therapy can lead to side effects such as lipodystrophy and long-term drug toxicity, and markers of inflammation associated with HIV infection can remain elevated and are associated with increased morbidity.3 For the more than one-third of PLWHA in the United States aged >50, control of aging-associated illnesses such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes may be complicated by HIV treatment.4

Various morbidity measures are used to monitor the health of PLWHA, including biomedical measures (eg, CD4 counts and viral loads), outpatient care use (eg, physician and emergency department visits), and inpatient hospitalization data. Inpatient hospitalization data capture information on the more severe spectrum of illness of PLWHA. Several changes took place during 2008-2014 that may have affected hospitalization rates among PLWHA in Illinois, including passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010,5 which increased the proportion of people with health care insurance in Illinois6; national guidelines that recommended initiation of HIV treatment regardless of disease stage7; efforts to expand access to HIV care8; and increased HIV testing initiatives.9 This study examined trends in hospitalization rates among PLWHA and the overall Illinois hospitalized population from 2008 through 2014.

Methods

This study used hospital discharge data reported to the Illinois Department of Public Health during 2008-2014 (11.2 million hospitalizations) to analyze hospitalizations among both PLWHA and the overall Illinois hospitalized population. Data are reported to the Illinois Department of Public Health from all acute-care hospitals, specialty hospitals, and ambulatory surgical treatment centers in Illinois.10

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes were used to classify diagnoses associated with hospital use during this period.11 To identify HIV/AIDS hospitalizations, the following ICD-9-CM codes were used: 042 (HIV disease), 079.53 (HIV-2), 795.71 (nonspecific serologic evidence of HIV), and V08 (asymptomatic HIV infection status). Hospitalizations with a principal diagnostic code (ie, the first-listed diagnosis) with one of the aforementioned ICD-9-CM HIV codes indicating that a patient was hospitalized because of a complication of HIV infection were classified as principal HIV hospitalizations. For these hospitalizations, the subsequent diagnostic code identified the associated HIV-related condition.12 The Illinois hospital discharge data set included up to 25 diagnostic codes for each hospitalization. An HIV diagnostic code in any of the other 24 nonprincipal diagnostic codes indicated that the patient was known to have HIV but that the hospitalization was the result of other cause(s). These hospitalizations were classified as secondary HIV hospitalizations.

The Illinois Electronic HIV/AIDS Registry (eHARS) maintains data on people diagnosed with HIV in Illinois; it has data on >95% of the people estimated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to have been newly diagnosed with HIV in Illinois annually.13 To determine annual hospitalization rates among PLWHA in Illinois, the annual number of HIV hospitalizations was divided by the number of PLWHA indicated in eHARS as alive and residing in Illinois at the end of each calendar year. Overall Illinois hospitalization rates were calculated using intercensal population estimates from the US Census Bureau.14 Hospitalization rates among PLWHA were summarized by year of hospitalization (2008-2014), age group (<25, 25-44, 45-64, and ≥65 years), sex (male, female), and racial/ethnic group (Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic other).

Joinpoint regression analysis, using the JoinPoint Regression Program version 4.5.0.1, was used to determine the estimated annual percentage change (APC) of hospitalization rates and to identify whether any significant breaks in the trend of hospitalization occurred among all PLWHA in Illinois. This software uses nonparametric permutation techniques to identify the smallest number of joinpoints that fit the data.15 The estimated slope for each portion of the line from the best fit model was then back-transformed to calculate a modeled APC.16 The significance test of the modeled APC was based on an asymptotic t test; P < .05 was considered to be significant.16 In this study, a maximum of 1 joinpoint was allowed for each estimation.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality single-level diagnosis Clinical Classification System was used to classify the large number of ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes into 285 clinically meaningful categories.17 These categories were used to identify the principal reasons for hospitalization and to identify the 15 most common comorbidities across all 25 diagnostic codes for hospitalizations among both PLWHA and the overall Illinois hospitalized population. Finally, this study identified the proportion of hospitalizations resulting in death among PLWHA and the overall Illinois hospitalized population.

This study was deemed public health nonresearch by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response Human Subjects Review Board.

Results

Trends in Overall, Principal HIV, and Secondary HIV Hospitalization Rates

Of 10 980 principal HIV hospitalizations in Illinois during 2008-2014, ICD-9-CM code 042 accounted for 99.8% (n = 10 967), V08 for 0.2% (n = 22), and 795.71 for <0.1% (n = 1) of hospitalizations; no hospitalizations were coded as 079.53. Despite an increase in the number of diagnosed PLWHA in Illinois (from 29 465 in 2008 to 36 965 in 2014), the annual number of principal HIV hospitalizations decreased by 35% (from 2093 hospitalizations in 2008 to 1350 hospitalizations in 2014). A smaller decline occurred in the annual number of secondary HIV hospitalizations (from 8709 hospitalizations in 2008 to 7879 hospitalizations in 2014). Hospitalizations with any HIV diagnosis (principal or secondary) accounted for 70 967 (0.6%) of the 11.2 million hospitalizations in Illinois during 2008-2014.

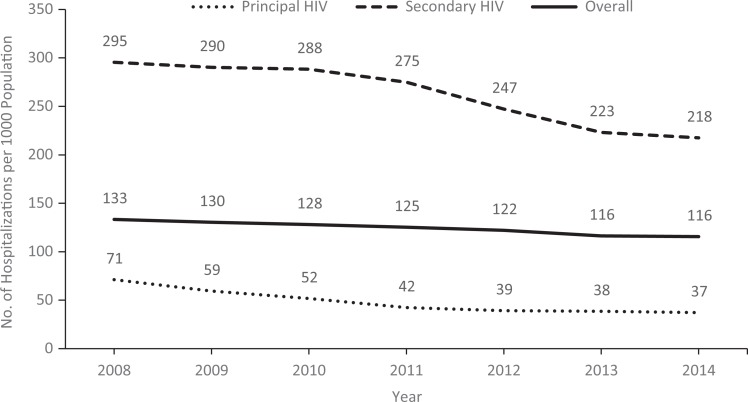

The rate of principal HIV hospitalizations per 1000 PLWHA declined by 48%, from 71 in 2008 to 37 in 2014 (Figure 1). The APC from 2008 to 2011 was –16.0% (P = .003) and from 2011 to 2014 was –4.5% (P = .05). The rate of secondary HIV hospitalizations per 1000 PLWHA declined by 26% overall, from 295 in 2008 to 218 in 2014, with no significant decline from 2008 to 2010 and a decrease of –7.4% annually from 2010 to 2014 (P = .03). By comparison, hospitalization rates per 1000 population for the overall Illinois hospitalized population declined consistently by an average of –2.5% annually, from 133 in 2008 to 116 in 2014 (P < .001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rates for principal HIV hospitalizations (n = 10 980), secondary HIV hospitalizations (n = 59 987), and overall hospitalizations (n = 11.2 million), by year, Illinois, 2008-2014. Principal HIV hospitalizations are hospitalizations with a principal diagnostic code (ie, the first-listed diagnosis) with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) HIV codes 042, 079.53, or 795.71 indicating that a patient was hospitalized because of a complication of HIV infection.11 Secondary HIV hospitalizations are hospitalizations with an ICD-9-CM HIV code as any nonprincipal diagnostic code. Data sources: Illinois Department of Public Health, hospital discharge data10; Illinois HIV surveillance data13; and US Census population estimates, 2008-2014.14

Trends in Principal HIV Hospitalization Rates by Demographic Group

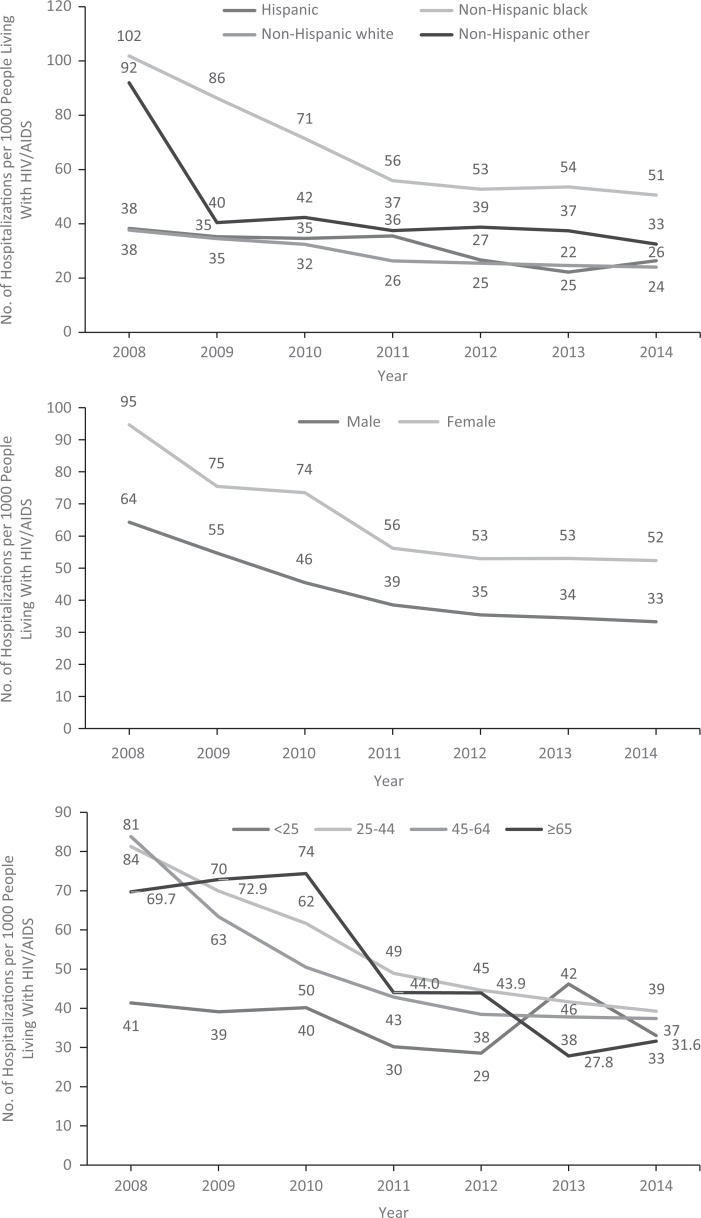

Rates of principal HIV hospitalizations per 1000 PLWHA declined for all racial/ethnic groups from 2008 to 2014 (Figure 2). Non-Hispanic black PLWHA accounted for 66% of principal HIV hospitalizations and had the highest rate of HIV hospitalizations during 2008-2014 (66.4 hospitalizations per 1000 PLWHA). From 2008 to 2011, the APC in the primary hospitalization rate among non-Hispanic black PLWHA was –18.2% (P = .005); however, from 2011 to 2014, the APC was –3.7% and not significant (P = .14). Among non-Hispanic white PLWHA (APC = –7.9%, P < .001) and Hispanic PLWHA (APC = –7.6%, P = .01), the annual APC was stable from 2008 to 2014. As a result, although the principal HIV hospitalization rate per 1000 population among non-Hispanic black PLWHA (101.9) was 2.7 times the rate of non-Hispanic white PLWHA in 2008 (37.7), by 2011 it had declined to 55.9, which was 2.1 times the rate of non-Hispanic white PLWHA (26.3). This level of disparity persisted through 2014, when non-Hispanic black PLWHA had a hospitalization rate per 1000 population of 50.6 compared with 24.0 for non-Hispanic white PLWHA.

Figure 2.

Rates for principal hospitalizations (n = 10 980) among people living with HIV/AIDS, by race/ethnicity, sex, age group, and year, Illinois, 2008-2014. Excluded were 332 hospitalizations for which the patient’s ZIP code indicated the patient did not reside in Illinois. Data sources: Illinois Department of Public Health hospital discharge data10; Illinois HIV surveillance data13; and US Census population estimates, 2008-2014.14

The rate of principal HIV hospitalizations was higher among women than among men during 2008-2014 (Figure 2). Although the overall decline in HIV hospitalization rates from 2008 to 2014 among women (from 94.6 to 52.4 hospitalizations per 1000 PLWHA) and men (from 64.4 to 33.3 hospitalizations per 1000 PLWHA) was similar (45%), among women, the APC was –9.9% (P = .002), with no joinpoints identified. Among men, from 2008 to 2011, the decline in the hospitalization rate was steep, with an APC of –16.2% (P < .001), but from 2011 to 2014, the APC declined to –4.7% (P = .014).

The rate of principal HIV hospitalizations declined across all age groups from 2008 to 2014 (Figure 2). The largest decline (55%) was among adults aged 45-64, from 83.8 to 37.4 hospitalizations per 1000 PLWHA, although this age group had the highest annual number of HIV hospitalizations (689 HIV hospitalizations in 2014). In this age group, the APC from 2008 to 2011 was –20.8% (P = .002) but declined from 2011 to 2014 to –3.4% (P = .10). In 2014, the rate of HIV hospitalizations was highest among adults aged 25-44 (39.3 hospitalizations per 1000 PLWHA and a total of 533 hospitalizations). From 2008 to 2014, the APC in the hospitalization rate in this age group was –12.2% (P < .001), with no break in trend detected. Because of the small number of hospitalizations (<75 per year in each age group) among PLWHA aged <25 and ≥65, annual hospitalization rates in these age groups varied widely during 2008-2014 and trends could not be assessed.

Comorbidities Among PLWHA

Principal diagnostic codes

Among the 70 067 hospitalizations with any HIV diagnosis during 2008-2014, the most common principal diagnosis listed for hospitalization was HIV infection. However, principal HIV hospitalizations as a proportion of hospitalizations with any HIV diagnosis decreased from 19.4% of 10 802 principal HIV hospitalizations in 2008 to 14.6% of 9229 principal HIV hospitalizations in 2014 (Table 2). During 2008-2014, the most common condition associated with principal HIV hospitalizations was pneumonia, followed by mycoses, septicemia, acute renal failure, and adult respiratory failure (Table 1). However, the proportion of principal HIV hospitalizations with pneumonia listed as the associated diagnosis decreased from 23% in 2008 to 17% in 2014 (APC = –5.3%; P = .01).

Table 2.

Fifteen most common principal diagnoses among patients hospitalized with HIVa and percentage of primary and secondary hospitalizations, by year, Illinois, 2008-2014b

| Rank | 2008 (n = 10 802) | 2009 (n = 10 741) | 2010 (n = 10 806) | 2011 (n = 10 432) | 2012 (n = 9753) | 2013 (n = 9204) | 2014 (n = 9229) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | |

| 1 | HIV infection | 19.4 | HIV infection | 17.0 | HIV infection | 15.2 | HIV infection | 13.3 | HIV infection | 13.7 | HIV infection | 14.7 | HIV infection | 14.6 |

| 2 | Mood disorders | 9.4 | Substance-related disorders | 9.1 | Substance-related disorders | 10.1 | Substance-related disorders | 8.7 | Mood disorders | 8.7 | Mood disorders | 8.6 | Mood disorders | 8.6 |

| 3 | Substance-related disorders | 8.0 | Mood disorders | 8.4 | Mood disorders | 7.3 | Mood disorders | 8.5 | Substance-related disorders | 8.0 | Substance-related disorders | 5.4 | Substance-related disorders | 4.8 |

| 4 | Schizophrenia | 4.0 | Pneumonia | 4.2 | Schizophrenia | 4.6 | Schizophrenia | 4.8 | Schizophrenia | 4.5 | Schizophrenia | 4.2 | Schizophrenia | 4.2 |

| 5 | Pneumonia | 4.5 | Schizophrenia | 4.0 | Pneumonia | 4.1 | Pneumonia | 4.1 | Pneumonia | 3.8 | Pneumonia | 3.7 | Septicemia | 3.5 |

| 6 | Septicemia | 1.8 | Skin infection | 2.5 | Skin infection | 2.4 | Skin infection | 2.9 | Septicemia | 3.0 | Septicemia | 3.1 | Pneumonia | 3.0 |

| 7 | Skin infection | 2.6 | Complications device | 1.8 | Septicemia | 2.4 | Septicemia | 2.5 | Skin infection | 2.3 | Skin infection | 2.1 | Skin infection | 2.1 |

| 8 | Complications device | 1.6 | Septicemia | 1.8 | CHF (non–high blood pressure) | 2.0 | CHF (non–high blood pressure) | 1.8 | Alcohol-related disorders | 1.7 | Complications device | 1.9 | CHF (non–high blood pressure) | 2.0 |

| 9 | CHF (non–high blood pressure) | 1.6 | CHF (non–high blood pressure) | 1.7 | Complications device | 1.8 | Complications device | 1.8 | COPD | 1.6 | Acute renal failure | 1.7 | Alcohol-related disorders | 1.8 |

| 10 | Alcohol-related disorders | 1.4 | Alcohol-related disorders | 1.6 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 1.6 | Alcohol-related disorders | 1.6 | CHF (non–high blood pressure) | 1.6 | Asthma | 1.6 | Complications device | 1.8 |

| 11 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 1.4 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 1.5 | Asthma | 1.5 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 1.6 | Complications device | 1.5 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 1.6 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 1.8 |

| 12 | Asthma | 1.3 | Chest pain | 1.4 | Chest pain | 1.5 | COPD | 1.6 | Acute renal failure | 1.4 | Alcohol-related disorders | 1.5 | COPD | 1.6 |

| 13 | COPD | 0.9 | Pancreas disorders | 1.3 | Alcohol-related disorders | 1.5 | Asthma | 1.5 | Chest pain | 1.3 | COPD | 1.4 | Asthma | 1.6 |

| 14 | Chest pain | 1.6 | COPD | 1.2 | COPD | 1.4 | Maintenance chemotherapy or radiotherapy | 1.4 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 1.3 | CHF (non–high blood pressure) | 1.4 | Maintenance chemotherapy or radiotherapy | 1.5 |

| 15 | Acute renal failure | 0.8 | Hypertension complications | 1.2 | Acute renal failure | 1.1 | Chest pain | 1.3 | Asthma | 1.2 | Chest pain | 1.3 | Acute renal failure | 1.5 |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder.

a Includes principal and secondary HIV hospitalizations. Principal HIV hospitalizations are hospitalizations with a principal diagnostic code (ie, the first-listed diagnosis) with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) HIV codes 042, 079.53, or 795.71 indicating that a patient was hospitalized because of a complication of HIV infection.11 Secondary HIV hospitalizations are hospitalizations with an ICD-9-CM HIV code as any nonprincipal diagnostic code.

Table 1.

Fifteen most common conditions associated with principal HIV hospitalizationsa and percentage of total principal HIV hospitalizations, by year, Illinois, 2008-2014b

| Rank | 2008 (n = 2093) | 2009 (n = 1821) | 2010 (n = 1640) | 2011 (n = 1392) | 2012 (n = 1133) | 2013 (n = 1351) | 2014 (n = 1350) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | |

| 1 | Pneumonia | 23.1 | Pneumonia | 19.7 | Pneumonia | 18.8 | Pneumonia | 21.2 | Pneumonia | 17.0 | Pneumonia | 16.3 | Pneumonia | 16.7 |

| 2 | Mycoses | 7.8 | Mycoses | 8.1 | Mycoses | 7.6 | Adult respiratory failure | 7.0 | Septicemia | 7.4 | Septicemia | 8.4 | Septicemia | 9.8 |

| 3 | Septicemia | 6.3 | Acute renal failure | 6.9 | Acute renal failure | 7.4 | Mycoses | 6.8 | Adult respiratory failure | 6.3 | Mycoses | 6.8 | Adult respiratory failure | 7.7 |

| 4 | Acute renal failure | 4.7 | Septicemia | 5.3 | Septicemia | 6.8 | Septicemia | 6.7 | Mycoses | 5.5 | Adult respiratory failure | 6.1 | Mycoses | 6.0 |

| 5 | Adult respiratory failure | 3.3 | Adult respiratory failure | 4.9 | Adult respiratory failure | 4.8 | Chronic kidney disease | 4.5 | Chronic kidney disease | 4.3 | Nutrient deficiencies | 5.7 | Acute renal failure | 4.5 |

| 6 | Hepatitis | 3.0 | Anemia | 3.6 | Nutrient deficiencies | 4.4 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 3.5 | Anemia | 4.3 | Acute renal failure | 5.0 | Chronic kidney disease | 4.1 |

| 7 | Chronic kidney disease | 3.0 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 3.5 | Anemia | 3.5 | Acute renal failure | 3.2 | Nutrient deficiencies | 3.8 | Chronic kidney disease | 4.7 | Nutrient deficiencies | 3.9 |

| 8 | Nutrient deficiencies | 2.7 | Nutrient deficiencies | 3.2 | Chronic kidney disease | 3.4 | Nutrient deficiencies | 3.1 | Acute renal failure | 3.7 | Anemia | 3.3 | Anemia | 3.8 |

| 9 | Anemia | 2.6 | Chronic kidney disease | 3.2 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 2.8 | Anemia | 2.6 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 3.6 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 2.7 | Meningitis | 3.1 |

| 10 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 2.6 | Viral infection | 2.6 | Urinary tract infection | 2.4 | Viral infection | 2.4 | Meningitis | 1.8 | Viral infection | 2.2 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 2.9 |

| 11 | Viral infection | 2.2 | Hepatitis | 2.1 | Viral infection | 2.1 | Other nervous system disorders | 2.4 | Other nervous system disorders | 1.7 | Meningitis | 2.2 | Other nervous system disorders | 2.4 |

| 12 | Other nervous system disorders | 2.1 | Other nervous system disorders | 1.8 | Other nervous system disorders | 2.0 | Meningitis | 2.2 | Hepatitis | 1.7 | Other bacterial infection | 2.2 | Other bacterial infection | 2.0 |

| 13 | Urinary tract infection | 1.9 | Urinary tract infection | 1.8 | Hepatitis | 1.7 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1.7 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1.7 | Intestinal infection | 1.9 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1.7 |

| 14 | Meningitis | 1.6 | Skin infection | 1.6 | Pancreas disorders | 1.6 | Other principal cancer | 1.5 | Urinary tract infection | 1.6 | Hepatitis | 1.4 | Viral infection | 1.7 |

| 15 | Other bacterial infection | 1.6 | Meningitis | 1.5 | Meningitis | 1.6 | Intestinal infection | 1.4 | Viral infection | 1.4 | Other nervous system disorders | 1.3 | Intestinal infection | 1.4 |

a Principal hospitalizations are hospitalizations with a principal diagnostic code (ie, the first-listed diagnosis) as International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification HIV codes 042, 079.53, or 795.71 indicating that a patient was hospitalized because of a complication of HIV infection.11

Mental health diagnoses, in particular mood disorders, substance-related diagnoses, and schizophrenia, were listed as the principal diagnosis for 18% to 22% of hospitalizations among PLWHA during 2008-2014. This percentage was higher than among the overall Illinois hospitalized population, where these principal diagnoses combined accounted for 6% to 7% of hospitalizations. Principal diagnoses that were less common among hospitalized PLWHA compared with the overall Illinois hospitalized population included dysrhythmia, which accounted for 0.4% to 0.7% of hospitalizations among PLWHA compared with 1.8% to 1.9% of overall Illinois hospitalizations; osteoarthrosis, which accounted for 0.2% to 0.5% of hospitalizations among PLWHA compared with 2.0% to 2.9% of overall Illinois hospitalizations; and congestive heart failure (non–high blood pressure), which accounted for 1.4% to 2.0% of hospitalizations among PLWHA compared with 2.4% to 2.6% of overall Illinois hospitalizations.

All diagnostic codes

Of 25 diagnostic codes included in the hospital discharge data, after HIV infection, the most common diagnoses among patients hospitalized with an HIV diagnosis during 2008-2014 were anemia (31% of hospitalizations), fluid or electrolyte disorders (30% of hospitalizations), and hypertension (28% of hospitalizations) (Table 3). These comorbidities were also common in the overall Illinois hospitalized population. In 2014, 20% of overall Illinois hospitalizations included a diagnosis of anemia, 30% a diagnosis of fluid or electrolyte disorders, and 33% a diagnosis of hypertension. However, during 2008-2014, 18% to 22% of hospitalized PLWHA had a hepatitis diagnosis, a higher proportion than among the overall Illinois hospitalized population (1.4%-1.5%). Coronary atherosclerosis, which was listed as a diagnosis for 31% to 33% of overall Illinois hospitalizations, was mentioned less often (8%-12%) as a comorbidity for hospitalized PLWHA.

Table 3.

Fifteen most common diagnoses among patients hospitalized with HIVa and percentage of primary and secondary HIV hospitalizations combined, by year, Illinois, 2008-2014b

| Rank | 2008 (n = 10 802) | 2009 (n = 10 741) | 2010 (n = 10 806) | 2011 (n = 10 432) | 2012 (n = 9753) | 2013 (n = 9204) | 2014 (n = 9229) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | Condition | % | |

| 1 | HIV infection | 100.0 | HIV infection | 100.0 | HIV infection | 100.0 | HIV infection | 100.0 | HIV infection | 100.0 | HIV infection | 100.0 | HIV infection | 100.0 |

| 2 | Anemia | 27.7 | Anemia | 28.8 | Anemia | 28.8 | Unclassifiedc | 30.6 | Unclassifiedc | 34.2 | Unclassifiedc | 38.4 | Unclassifiedc | 40.4 |

| 3 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 24.7 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 25.1 | Unclassifiedc | 26.7 | Anemia | 28.5 | Anemia | 29.5 | Anemia | 32.0 | Anemia | 31.1 |

| 4 | Hypertension | 23.9 | Unclassifiedc | 25.0 | Hypertension | 25.6 | Hypertension | 26.5 | Hypertension | 27.2 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 28.9 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 30.0 |

| 5 | Unclassifiedc | 23.9 | Hypertension | 24.7 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 25.5 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 24.6 | Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 26.4 | Hypertension | 27.1 | Hypertension | 28.3 |

| 6 | Hepatitis | 21.2 | Hepatitis | 21.1 | Hepatitis | 20.6 | Hepatitis | 20.0 | Other aftercare | 19.8 | Other aftercare | 20.2 | Other aftercare | 21.0 |

| 7 | Pneumonia | 17.0 | Asthma | 16.8 | Asthma | 16.9 | Asthma | 17.6 | Hepatitis | 18.8 | Hepatitis | 19.9 | Hepatitis | 19.2 |

| 8 | Asthma | 15.1 | Pneumonia | 15.9 | Chronic kidney disease | 15.8 | Chronic kidney disease | 16.4 | Asthma | 18.0 | Other nutritional disorders | 18.3 | Other nutritional disorders | 19.1 |

| 9 | Other GI disorders | 13.7 | Chronic kidney disease | 15.2 | Other GI disorders | 15.1 | Other aftercare | 14.9 | Other nutritional disorders | 16.1 | Chronic kidney disease | 17.7 | Chronic kidney disease | 18.9 |

| 10 | Chronic kidney disease | 13.7 | Other GI disorders | 14.3 | Pneumonia | 14.7 | Pneumonia | 14.5 | Other GI disorders | 16.1 | Asthma | 17.7 | Other nervous system disorders | 18.5 |

| 11 | Other nutritional disorders | 12.4 | Hypertension complications | 13.0 | Hypertension complications | 13.2 | Other GI disorders | 14.3 | Chronic kidney disease | 15.8 | Other GI disorders | 17.5 | Asthma | 18.4 |

| 12 | Hypertension complications | 11.7 | Other nutritional disorders | 12.2 | Other nervous system disorders | 12.9 | Hypertension complications | 14.2 | Other nervous system disorders | 14.8 | Other nervous system disorders | 16.6 | Other GI disorders | 17.1 |

| 13 | Other nervous system disorders | 11.5 | Mycoses | 11.3 | Other nutritional disorders | 12.7 | Other nutritional disorders | 13.9 | Pneumonia | 14.2 | Hypertension complications | 15.6 | Hypertension complications | 16.5 |

| 14 | Mycoses | 11.3 | Diabetes, no complications | 11.1 | Diabetes, no complications | 12.2 | Other nervous system disorders | 13.5 | Hypertension complications | 13.6 | Pneumonia | 14.7 | Disorders of lipid metabolism | 15.3 |

| 15 | Diabetes, no complications | 11.2 | Other nervous system disorders | 11.0 | Other aftercare | 11.7 | Diabetes, no complications | 12.9 | Diabetes, no complications | 12.6 | Disorders of lipid metabolism | 13.6 | Acute renal failure | 15.1 |

Abbreviation: GI, gastrointestinal.

a Includes principal and secondary HIV hospitalizations. Principal HIV hospitalizations are hospitalizations with a principal diagnostic code (ie, the first-listed diagnosis) with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) HIV codes 042, 079.53, or 795.71 indicating that a patient was hospitalized because of a complication of HIV infection.11 Secondary HIV hospitalizations are hospitalizations with an ICD-9-CM HIV code as any non-principal diagnostic code.

b Excluded were 332 hospitalizations in which the patient’s ZIP code indicated that the patient did not reside in Illinois. Data sources: Illinois Department of Public Health hospital discharge data10 and Illinois HIV surveillance data 2008-2014.13

c Unclassified hospitalizations represent various diagnoses that do not fit into other Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System (CCS) categories and that have been grouped together into 1 CCS category.17

Hospital-Based Mortality

During 2008-2014, patients hospitalized with a complication of HIV (principal HIV hospitalization) were much more likely to die during their hospitalization than the overall Illinois hospitalized population. Among PLWHA with a principal hospitalization, 4.1% to 6.6% of hospitalizations resulted in patient death with no significant trend identified during 2008-2014. Among the overall Illinois hospitalized population, 1.7% to 1.8% of hospitalizations resulted in patient death, and again, no significant trend occurred during 2008-2014.

Discussion

The decrease in both principal and secondary HIV hospitalization rates in Illinois from 2008 to 2014 is promising, with HIV hospitalization rates declining more rapidly than the overall Illinois hospitalization rate. Earlier initiation of diagnosis and treatment among PLWHA likely contributed to the decline in principal HIV hospitalizations.18 However, after a steep reduction in principal HIV hospitalization rates from 2008 to 2011, the rate of decline slowed from 2011 to 2014. This decreased rate of decline occurred among non-Hispanic black people, men, and those aged 45-64. Despite the decline in hospitalizations among PLWHA, in 2014, PLWHA were hospitalized at more than twice the rate of the overall Illinois hospitalized population and were more likely to die during their hospitalization.

During 2010-2014, women accounted for 18% of new HIV diagnoses in Illinois; in 2014, 1.2 women and 4.6 men per 1000 population had HIV/AIDS.2 Although men accounted for most PLWHA, women had a higher rate of principal HIV hospitalizations during 2008-2014. Women have higher all-cause hospitalization rates nationally,19 and other state and national analyses have also found higher principal HIV hospitalization rates among women compared with men.20,21 The higher rate of principal HIV hospitalizations among women compared with men in Illinois was not because of pregnancy-related HIV hospitalizations. In Illinois, rates of late HIV diagnosis, defined as either having AIDS at the time of initial HIV diagnosis or being diagnosed with AIDS within 12 months of initial HIV diagnosis, are similar among men and women.22 Additional research is needed to better understand the factors that contribute to higher principal HIV hospitalization rates among women with HIV/AIDS compared with men with HIV/AIDS.

Non-Hispanic black people had a higher prevalence of HIV in Illinois compared with all other racial/ethnic groups. The reduction in the principal HIV hospitalization rate among non-Hispanic black people from 2008 to 2011 indicates progress in HIV management in this population. However, since 2011, the disparity in principal HIV hospitalizations between non-Hispanic black people and those in other racial/ethnic groups has been consistent, with non-Hispanic black PLWHA hospitalized at double the rate of non-Hispanic white PLWHA. Higher HIV hospitalization rates among non-Hispanic black people compared with other racial/ethnic groups have also been found nationally.21

Most hospitalizations among PLWHA during 2008-2014 were for non–HIV-related conditions. Hospitalizations for mental health and substance use–related diagnoses accounted for a higher proportion of hospitalizations among PLWHA than among the overall Illinois hospitalized population and point to challenges that patients may face in adhering to treatment. About 20% of hospitalizations among PLWHA included hepatitis as a comorbidity, another factor complicating treatment of PLWHA. HIV/hepatitis C coinfection is associated with higher rates of hospital admission, compared with HIV mono-infection, including admissions for conditions not directly related to HIV infection.23,24 Hospitalized PLWHA were less likely than the overall Illinois hospitalized population to have such conditions as coronary atherosclerosis, congestive heart failure, and dysrhythmia. This finding is likely a reflection of the younger age distribution of PLWHA compared with the overall Illinois hospitalized population.25

A significant finding of this analysis was the reduction in rates of pneumonia among principal HIV hospitalizations. Pneumococcal vaccine is recommended as part of routine care for PLWHA, regardless of a patient’s CD4 count.26 In 2012, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices began recommending the use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, in addition to the already recommended 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, among immunocompromised adults.27 Use of these vaccines may have contributed to the reduction in rates of pneumonia among principal HIV hospitalizations, although additional analyses are needed to understand what caused this reduction.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the hospital discharge data were not de-duplicated; therefore, patients with a high number of repeat hospitalizations may have skewed the findings. Second, using ICD-9-CM codes to characterize patient illness may not accurately capture the reasons for a patient’s hospitalization because hospitals use these codes primarily for billing. Finally, not having data on patient HIV measures, such as CD4 counts and viral load, limited the ability of this study to understand the impact of individual HIV disease management on risk of hospitalization.

Conclusions

The Illinois Department of Public Health, with substantial federal support, has several initiatives in place to reach vulnerable populations living with HIV, including providing access to health care through the Ryan White Program, ensuring access to medication through the AIDS Drug Assistance Program, and supporting several linkage-to-care programs.2,8 The decline in principal HIV hospitalization rates from 2008 to 2014 by almost 50% is promising. However, disparities in hospitalization rates among subpopulations of PLWHA and a stagnation in the decline of principal HIV hospitalization rates since 2011 indicate the need for sustained, targeted interventions. Public health agencies, community-based organizations, and health care providers should work together to continue the positive trend in the reduction of hospitalization rates among PLWHA in Illinois.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks staff members from the Illinois Department of Public Health HIV Section and the Division of Patient Safety and Quality for access to data and review of this article. Dr Fangchao Ma and Dejan Jovanov provided substantial feedback and analytic support. As part of the clearance process, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) staff members who reviewed this article provided critical input, in particular, Dr W. Randolph Daley, Division of State and Local Readiness, Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by CDC funding opportunity announcement PS12-1201.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveill Rep. 2016;27:1–114. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed May 13, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Illinois Department of Public Health, Office of Health Protection, HIV/AIDS Section. Illinois integrated HIV prevention and care plan 2017-2021: a roadmap for collective action in Illinois. 2016. http://www.dph.illinois.gov/sites/default/files/publications/publicationsohp-illinoishivintegratedplan2017-2021_0.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 3. Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1525–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(3):453–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. US Government. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub L No. 111-148, as amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act, Pub. L No. 111-152 (2010).

- 6. Barnett JC, Vornovitsky MS. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2015. Current Population Reports, P60-257(RV) Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2016. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p60-257.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents. Last updated March 2012 https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/adultandadolescentgl003093.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 8. Illinois Public Health Association. Illinois HIV Care Connect. http://hivcareconnect.com/for-people-living-with-hiv. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 9. Illinois Department of Public Health. Counseling and testing sites. http://www.idph.state.il.us/aids/test_serve_sites.htm. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 10. Illinois Department of Public Health. Hospital discharge database. 2018. http://www.dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/prevention-wellness/patient-safety-quality/discharge-data. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 11. National Center for Health Statistics. International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification. Page updated June 2013 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Official authorized addenda: human immunodeficiency virus infection codes and official guidelines for coding and reporting IC-9-CM. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1994;43(RR-12):11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13. llinois Department of Public Health. Illinois Electronic HIV/AIDS Reporting System. 2008. –2014. http://www.dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/diseases-and-conditions/hiv-aids/hiv-surveillance. Accessed June 10, 2018.

- 14. US Census Bureau, Population Division. Population and housing unit estimates tables: annual estimates of the resident population. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/data/tables.All.html. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 15. National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.5.0.1. Bethesda, MD: Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xie L, Onysko J, Morrison H. Childhood cancer incidence in Canada: demographic and geographic variation of temporal trends (1992-2010). Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(3):79–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Last modified March 2017 https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 18. Song R, Hall HI, Green TA, Szwarcwald CL, Pantazis N. Using CD4 data to estimate HIV incidence, prevalence and percent of undiagnosed infections in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Brief #180. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Trends in the hospitalization of persons living with HIV/AIDS in California, 1988 to 2008. 2011. http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/documents/HID/HealthFacts/HealthFacts_HIV_AIDS_WEB.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 21. Bachhuber MA, Southern WN. Hospitalization rates of people living with HIV in the United States, 2009. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(2):178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Illinois Department of Public Health. Factsheet: late HIV diagnosis. 2014. http://www.dph.illinois.gov/sites/default/files/publications/1-25-16-OHP-HIV-factsheet-Late-HIV-Diagnosis.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 23. Norton BL, Park L, McGrath LJ, Proschold Bell RJ, Muir AJ, Naggie S. Health care utilization in HIV-infected patients: assessing the burden of hepatitis C virus coinfection. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(9):541–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Linas BP, Wang B, Smurzynski M, et al. The impact of HIV/HCV co-infection on health care utilization and disability: results of the ACTG Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials (ALLRT) cohort. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18(7):506–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Illinois Department of Public Health. 2014. Illinois HIV/AIDS epidemiology profile. 2016. http://www.dph.illinois.gov/sites/default/files/publications/1-27-16-OHP-HIVfactsheet-Overview.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2018.

- 26. Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(40):816–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]