Abstract

Background

Advance care planning (ACP) involves several behaviors that individuals undertake to prepare for future medical care should they lose decision-making capacity. The goal of this study was to assess whether playing a conversation game could motivate participants to engage in ACP.

Methods:

Sixty-eight English speaking, adult volunteers (n=17 games) from communities around Hershey, Pennsylvania and Lexington, Kentucky played a conversation card game about end-of-life issues. Readiness to engage in four ACP behaviors were measured by a validated questionnaire (based on the trans-theoretical model) immediately before and 3 months post-game and a semi-structured phone interview. These behaviors were: 1) completing a living will; 2) completing a health-care proxy; 3) discussing end-of-life wishes with loved ones; and 4) discussing quality versus quantity of life with loved ones.

Results:

Participants’ (n=68) mean age was 51.3 years (SD=0.7, range 22–88); 94% of participants were Caucasian and 67% were female. 78% of participants engaged in ACP behaviors within 3 months of playing the game (e.g. updating documents, discussing end-of-life issues). Furthermore, 73% of participants progressed in Stage of Change (ie. readiness) to perform at least one of the four behaviors. Scores on measures of Decisional Balance and Processes of Change increased significantly by 3 months post-intervention.

Conclusions:

This pilot study found that individuals who played a conversation game had high rates of performing ACP behaviors within three months. These findings suggest that using a game format may be a useful way to motivate people to perform important ACP behaviors.

Keywords: Advance care planning, end-of-life care, palliative care, advance directives, health behavior, communication

INTRODUCTION

Advance care planning (ACP) involves a process consisting of behaviors that individuals undertake to prepare for future medical care should they lose decision-making capacity. This process is multi-faceted and includes considering one’s values, goals, and preferences regarding medical care; discussing them with loved ones and healthcare providers; and documenting those wishes in the form of advance directives (such as a living will or healthcare proxy).1

Recent studies support the notion that when patients and their families discuss one another’s values and beliefs about end-of-life care, outcomes are improved for both patients and families.2–6 In one randomized controlled trial, when hospitalized patients had such discussions, their wishes were more likely to be followed, their stress, anxiety, and depression decreased, and both patients and their families were more satisfied with hospital care.2 In another randomized controlled study, structured conversations with trained facilitators and patients significantly improved surrogates’ understanding of patient preferences,5 and others have shown that ACP increases documentation of advance directives in the medical record from 9% to 45%.6

Though discussing values and beliefs has been shown to have positive outcomes for patients and their families, <25% of individuals engage in meaningful ACP discussions and <30% complete an advance directive document.7–9 Known barriers to ACP include 1) lack of opportunity for having ACP conversations;10–12 2) reluctance to discuss death and dying;11, 12 3) concerns about the impact of ACP on family dynamics;11, 13 and 4) time constraints for clinicians to devote to ACP.14–17

A promising intervention for addressing the first and second of these barriers is an end-of-life conversation game, called ‘My Gift of Grace.’ It is well recognized that games can be used to engage people in sensitive discussions18–20 as well as to stimulate behavior change in various health contexts.21 In a recent feasibility study participants reported that playing ‘My Gift of Grace’ resulted in satisfying, realistic, and enjoyable conversations about death and dying.22

In this pilot study, we report on this conversation game’s effect on motivating participants to engage in subsequent ACP behaviors (such as discussing end-of-life issues with loved ones, family, or completing advance directives). Using Prochaska’s Trans-theoretical model of behavior change,23 we hypothesized that participants who played ‘My Gift of Grace’ would advance in their stage of readiness to complete ACP behaviors.

METHODS

Conceptual Framework For Behavior Change

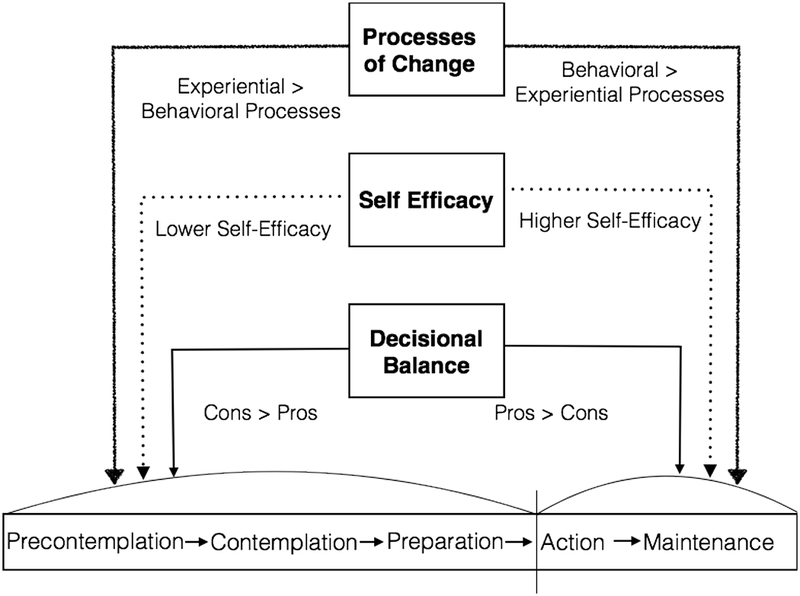

We selected Prochaska’s trans-theoretical model (TTM) of behavior change as our conceptual framework (Figure 1). An extensive literature spanning more than two decades provides ample foundation for applying this model to intentional behavior change across a wide variety of health behaviors, including ACP.23–28 Furthermore, several validated surveys have been developed that apply TTM to the measurement of behavior change in the ACP context, and research shows consistency between survey results and Prochaska’s theory.29 This model presumes that behavior change occurs incrementally through a process of five stages (“Stages of Change”), culminating in the ultimate target behavior.

Figure 1.

The trans-theoretfcal model.

In the context of end-of-life conversations, the five stages of change are: pre-contemplation (“I am not ready to discuss this”), contemplation (“I am considering talking about this with my family in the next 6 months”), preparation (“I am going to talk about this in the next 30 days”), action (“I have talked with my family in the past 6 months”), and maintenance (“We discussed this >6 months ago”).30 Individuals who are in the maintenance stage may also re-engage in the ACP process by revisiting conversations with loved ones periodically.

These stages are influenced by, and are dependent upon, three other constructs: decisional balance, processes of change, and self-efficacy (Figure 1). Decisional balance involves attitudes about the ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ of behavior change. Processes of change represent behavioral activities (e.g. seeking out information) and/or experiential processes (e.g. supportive partnerships with loved ones) that may alter one’s perceptions of behavior and their intention to change. Self-efficacy involves one’s level of confidence in the ability to change one’s behavior.

As individuals advance through the five stages of change, each of these constructs is affected. Decisional balance shifts in favor of ‘pro’ statements that reflect positive aspects of ACP (versus the ‘cons’ or negative aspects of ACP); processes of change become more pronounced and may shift in nature (eg. greater focus on behaviors versus experiential thinking) and self-efficacy rises (Figure 1).

Subjects and Study Design

Description of Game Intervention

The ‘My Gift of Grace’ game was chosen for this study because it was designed to promote ACP engagement. The game was developed by a third party using patient-centered interviews and focus groups of >100 patients, content experts, caregivers, and other stakeholders, and prior research found this game effective for stimulating end-of-life conversations.22

The game uses 47 question cards to prompt discussions about death, dying, and end-of-life issues, and are ordered with regard to pacing, content and emotional depth. Some questions ask about medical decision-making (e.g. “When you think about care at the end of your life, do you worry more about not getting enough care, getting overly aggressive care, or other?” and “In order to provide the best care possible, what three non-medical facts should your doctor know about you?”). Other questions are intended to provide emotional respite for players (e.g. “What music do you want to be listening to on your last day alive?” and “If you could pick anyone to sing at your memorial service, who would it be and what would they sing?”). Players take turns drawing cards and reading them to the group, then independently write down their answers, and then take turns sharing and discussing their responses. Players exchange game tokens to express gratitude, or acknowledge poignant, emotional, or thoughtful responses. The present study used 20 of the questions that were found effective at eliciting meaningful, clinically relevant discussions.31, 32 An initial coin toss, whose outcome is not revealed until the end of the game, determines whether the player with the most or the least game chips wins. Games were stopped after two hours, or when participants finished discussing all 20 questions (whichever came first).

Participants

We used local advertisements to recruit 70 adults from communities in central Pennsylvania (n=57; 14 games) and Lexington, Kentucky (n=13; 4 games). Games were played by groups of 2–6 participants. Eligibility criteria included being: 1) English-speaking; 2) >18 years old; 3) without self-reported hearing impairment; and 4) able to engage in conversation for 2–3 hours. Participants were given the option of playing the game with family, friends, or strangers. Institutional Review Boards from Penn State Hershey Medical Center and University of Kentucky approved all study procedures. Data were collected from June 2014 to January 2015. One game was excluded from analysis due to deviation from protocol, resulting in a final sample of 16 games and 68 participants.

Study Design and Measures

Prior to playing the game, participants individually completed written questionnaires eliciting demographics, experiences with medical decision-making, and readiness to engage in ACP. Based on prior work by Fried, we selected four key ACP behaviors to measure pre- and post-intervention: 1) completing a living will (LW); 2) identifying and naming a health-care proxy; 3) discussing end-of-life wishes with loved ones; 4) discussing quality versus quantity of life with loved ones.1, 29 Readiness to engage in these behaviors was measured by questionnaire immediately before the game and via a semi-structured phone interview 3 months afterwards. To measure the trans-theoretical model constructs of Stage of Change, Decisional Balance, and Processes of Change, patients completed validated questionnaires based on the trans-theoretical model that demonstrate high factor loading (>0.5) and excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.76–0.93).29 Participants received compensation of $30 and a copy of the game after the 2.5 hour study session and an additional $10.00 for the follow-up phone call..

Stages of Change

The Stages of Change portion of the questionnaire consists of 22 items culminating in identification of the appropriate stage of change (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, or maintenance) for each of the four ACP behaviors. Stage of Change was compared (pre- to 3-months post-intervention) for each of the four behaviors, and an indicator variable was defined based on the direction of movement. If participants advanced in the Stage of Change continuum, they were categorized as ‘forward’. If there was no change in stage, they were assigned ‘stable’. If they moved backwards in stage of change (i.e., contemplation to pre-contemplation) they were categorized as ‘backward’. Participants with missing data were categorized as “unstageable,” and stage movement that was nonsensical (i.e, action to pre-contemplation) was categorized as “conflicting”. Behaviors were considered completed if participants moved into the “action” stage for any behavior, or reported a behavior during the 3-month follow-up phone interview (see below).

Decisional Balance

The Decisional Balance portion of the questionnaire contained 12 statements about the ‘Pros’ (6 items) and ‘Cons’ (6 items) of doing ACP. Example statements are: “Pro”–‘Doing advance care planning would simplify how decisions would be made if I were very ill,’ and “Con” – ‘I don’t want to talk with loved ones about end-of-life decisions.’29 Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement using a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree, 5=strongly disagree). Both sets of statements were summed separately to calculate a composite score for each (6=strongly agree; 30=strongly disagree).

Processes of Change Questionnaires

The Processes of Change (POC) portion of the questionnaire consists of 15 items that represent both experiential (6-items) and behavioral processes (9-items) that influence behavior change. Respondents rated each item based on how often they used each process within the last month (1=almost never; 5=almost always). Experiential and behavioral processes were summed separately to calculate a composite score for each (6–30; 30=almost always). Example items are: experiential process–‘I look for information on ACP’; behavioral process–‘I feel committed to doing ACP.’29

3-month Follow-up Phone Interviews

Immediately after the game, participants completed questionnaires about the game experience and participated in a focus group discussion whose results are reported elsewhere.22 In an audio-recorded phone interview 3 months later, the same trans-theoretical model questionnaires were asked, along with a semi-structured interview to identify additional behaviors (such as gathering written ACP information, making funeral arrangements, etc.) Participants were also asked, “Since playing the game at the study session, have you performed any additional activities to prepare for future medical decisions or end-of-life issues?” with additional prompts such as “Did you discuss these issues with anyone (and if so, who)”; “Did you play the game with anyone since the study session (and if so, who)”; and “Did you complete any documents stating your wishes?” Audio was transcribed verbatim.

Statistical Analyses of Questionnaires

Demographic data were analyzed and reported as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages of the direction of movement were calculated for each participant and for each of the four behaviors. We performed paired t-tests to compare differences between pre and post-intervention scores on Decisional Balance and POC. Significance level was set at 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.

Analyses of Phone Interviews

Initially, one author (JMR) reviewed all phone interview transcripts to identify the ACP behaviors that were reported by participants. These behaviors were then grouped into the following categories: 1) had an ACP conversation with a loved one; 2) had an ACP conversation with a healthcare provider; 3) played the game again (formally by following the game rules or informally by just reviewing the card questions); 4) updated, reviewed, organized, or created an advance directive; 5) gathered written information about ACP or long-term care; 6) made nursing home or funeral arrangements (or made appointments to do so); and 7) made an appointment with a healthcare provider or lawyer (but had not yet attended). Then, a separate coder reviewed transcripts and, for each participant, determined whether the behavior described by was ‘performed’ or ‘not performed’. Behaviors were categorized as ‘performed’ only if they occurred after the study session (not during). Finally, a second author (LJV) reviewed the coded data for accuracy and consistency with transcripts. Discrepancies were reviewed by an author (JMR) and resolved by group discussion. Descriptive statistics were complied of the frequency and type of behaviors performed.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 51.3 years (SD=0.7, range 22–88); 94% of participants were Caucasian and 67% were female. The mean game duration was 91 minutes (SD=25.6), with no difference in games played among families (n=3), strangers (n=4), friends (n=6), or mixed groups (n=4). No games were terminated prior to completion and no participants reported or displayed emotional distress during the game or during the follow-up interviews. Most participants reported having lost a relative or close friend in the last 5 years (79%); but <18% reported having made medical decisions for another individual in that same time frame; and <9% reported having made a major medical decision for themselves in the past 5 years.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n=17 games)

| Demographics (N=68) | |

|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 51.3 (0.7) |

| Gender, N (%) | |

| Female | 46 (67.6) |

| Male | 22 (32.4) |

| Race, N (%) | |

| White | 64 (94.1) |

| African American | 1 (1.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (1.5) |

| 2 or more | 2 (2.9) |

| Marital Status, N (%) | |

| Single | 8 (26.5) |

| Married | 36 (52.9) |

| Divorced | 8 (11.8) |

| Widowed, Other | 6 (8.9) |

| Education, N (%) | |

| High school | 6 (8.8) |

| Some College | 15 (22.1) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 24 (35.3) |

| Graduate Degree | 23 (33.8) |

| Self-rated Health Status, M (SD) | 1.9 (0.7) |

Percentages may not add to100 because some participants had performed ACP behaviors >5 years prior or due to missing data.

ACP Behaviors

We assessed ACP behaviors in two ways: 1) by identifying behaviors during the 3-month follow-up interview, and 2) by identifying participants whose follow-up stage of change moved into ‘Action’ stage for any of the 4 measured ACP behaviors. During phone interviews, 78% of participants reported completing an ACP behavior within 3 months after the intervention (Table 2). In contrast to the 21% of participants who discussed end-of-life issues with loved ones prior to the intervention, 60% did so post-intervention. Additionally, among the 33 participants who did not already have a living will, 21% created a living will within 3 months of the intervention. Similarly, of the 37 participants who did not already have a healthcare proxy, 19% named a healthcare proxy within 3 months of the study. We also found that 46% of the participants had already completed a living will (i.e., were in the maintenance stage) and 39% had already completed a healthcare proxy prior to the study

Table 2.

ACP Behaviors Performed by Participants

| Behaviors Assessed via Phone Interview 3 months after Intervention | n (%) |

| Talked with friends, family or loved ones about end-of-life issues in general | 44 (73) |

| Played the game again or reviewed game cards with family or friends | 16 (27) |

| Updated, reviewed, organized or created an advance directive | 12 (20) |

| Told other about the game experience | 6 (10) |

| Gathered written information (brochures, forms, etc.) | 4 (7) |

| Made nursing home, funeral home arrangements or made appointments to do so | 4 (7) |

| Made appointment with physician or lawyer | 2 (3) |

| Discussed end-of-life issues with healthcare provider | 2 (3) |

| Performed at least one of the above behaviors (via phone interview) | 47 (78) |

| Behaviors Assessed by Action Stage of Survey | Action Stage Pre-Game (N=68) n(%) | Action Stage 3-months Post-Game (N=60) n(%) | Percent Change since Game |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed a living will | 0 (0) | 7 (11.6) | 11.6% |

| Completed a healthcare proxy | 1 (1.5) | 7 (11.6) | 10.1% |

| Talked with loved ones about end-of-life issues | 14 (20.6) | 34 (56.7) | 36.1% |

| Talked with loved ones about quality of life versus quantity of life | 14 (20.9) | 36 (60.0) | 39.1% |

Stages of Change

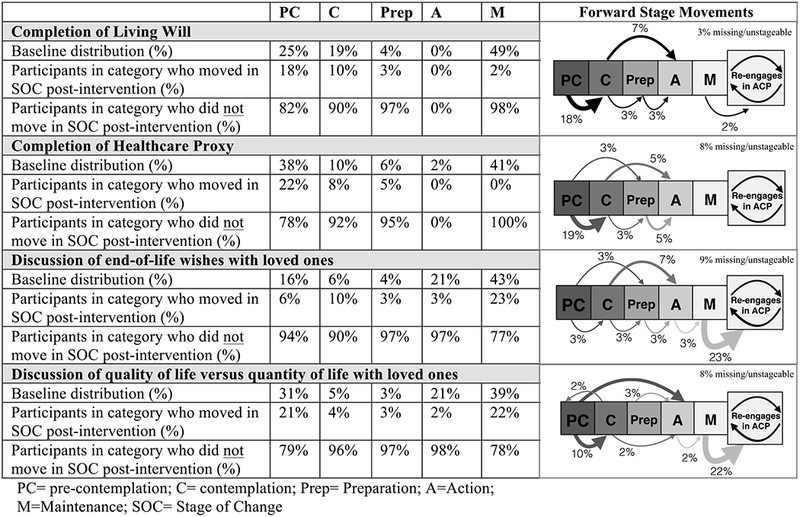

Figure 2 illustrates the movement in Stage of Change for each of the 4 ACP behaviors measured in the questionnaires (forward, stable, missing, or conflicting). We found that 73% of participants advanced in stage of change for at least one of the four ACP behaviors, and 44% of participants advanced in stage of change for at least two of the four ACP behaviors. Of the 46% of participants who had already had conversations with loved ones about end-of-life wishes (ie. were in maintenance stage prior to the intervention), half of those individuals (23%) re-initiated end-of-life conversations with loved ones within 3 months of the intervention. Similarly, of the 38% of individuals who had already discussed quality versus quantity of life with loved ones, over half (22%) re-initiated those discussions within 3 months after the intervention (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Stages of Change Pre- and 3 months Post-intervention

Decisional Balance and Processes of Change

We found that participants were significantly more likely post-intervention to agree with the ‘Pro’ statements about ACP on the Decisional Balance measure (p=0.02; Table 3), compared to pre-intervention. Similarly, we found that participants were significantly less likely post-intervention to agree with ‘Con’ statements about ACP on the Decisional Balance measure (p=0.001; Table 3) compared to pre-intervention. Scores were significantly higher 3 months after the intervention on both the experiential (p=0.002; Table 3) and behavioral (p=0.000; Table 3) processes of change, indicating that participants were more favorable toward ACP.

Table 3.

Other constructs of the trans-theoretical model

| Questionnaire Scale | Paired n | Pre-Game Mean (SD) | 3-month post-game mean (SD) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decisional Balance | Pros of ACP (6-items) | Scored 6–30; 6=strongly agrees with pros of ACP, 30= strongly disagrees with pros of ACP | 58 | 10.2 (3.9) | 8.9 (2.7) | 0.02 |

| Cons of ACP (6-items) | Scored 6–30; 6=strongly agrees with cons of ACP, 30= strongly disagrees with cons of ACP | 57 | 24.2 (3.9) | 25.6 (3.2) | 0.001 | |

| Process of Change | Experiential Processes of Change (6-items) | Scored 6–30; lower scores signifying never doing the ACP behavior | 55 | 13.6 (7.2) | 16.8 (6.2) | 0.002 |

| Behavioral Processes of Change (9-items) | Scored 9–45; lower scores signifying never doing the ACP behavior | 52 | 21.0 (10.6) | 25.4 (9.0) | 0.000 | |

DISCUSSION

This study found that participants who played an end-of-life conversation game had a high frequency of performing subsequent advance care planning (ACP) behaviors and/or advanced in their readiness to do so. We found that within 3 months of playing the game, 78% of participants engaged in at least one ACP behavior, the most common of which involved starting further ACP discussions with a family member or friend about end-of-life issues. Individuals also completed new (or reviewed old) advance directives, sought out written information about long-term care options, and did other activities key to the ACP process.1, 33 In addition to prior data showing that a conversation game can stimulate satisfying, realistic and clinically meaningful conversations,22, 31 the present results demonstrate that playing such a game can motivate individuals to perform critical ACP behaviors and/or advance their readiness to do so.

Given the minority of Americans who have had substantive ACP conversations, and the appeal of game activities, the present findings offer compelling evidence that a conversation game can be used not only to broach complex and sensitive issues about end-of-life issues, but also motivate individuals to engage in subsequent ACP behaviors. Almost three-quarters of participants in this study advanced in their stage of readiness to perform an ACP behavior, and following the conversation game, participants were significantly more likely to have a positive view of ACP activities, all of which is consistent with behavior change as predicted by the trans-theoretical model.23, 29 As such, the present findings have a strong conceptual grounding for explaining how this game intervention succeeds in moving participants towards behavior change with regard to ACP.

Even though 46% of our participants had completed a living will and 39% had assigned a healthcare proxy prior to the study, the game intervention motivated approximately half of those individuals to review their existing documents and/or to revisit end-of-life conversations with loved ones. This is a promising finding because it is widely agreed that in addition to completing advance directives, the most effective ACP also includes revisiting end-of-life related values, goals and beliefs in a series of conversations over time.1, 33

Establishing a conversational tool that actually compels participants to act is important because changing health behaviors is a notoriously difficult task to accomplish, particularly with regard to ACP. Despite agreement among patients and clinicians that meaningful ACP is important, it seldom occurs. Though many of ACP interventions have been attempted and several studied, (such as the community-based Respecting Choices Program34, POLST programs,35 and others,24 the vast majority of these interventions are complex, expensive, and typically require experienced clinicians, trained facilitators, and/or some formal support mechanism to be accomplished. Furthermore, to our knowledge, existing interventions still struggle to overcome a key barrier to engagement in the ACP process: the perceived unpleasant nature of conversations about end-of-life issues.

A game intervention reframes the very prospect of such conversations by casting them as enjoyable, positive experiences22 and does so via an inexpensive, self-guided tool that does not require physician involvement or integration with a healthcare system.

Our findings that game participants had high rates of completion of ACP behaviors are consistent with other studies that have found that games are an effective means for affecting behavior change. Game playing has been successfully used to address other emotionally charged health topics such as sexual health,18 cancer,19 post-traumatic stress disorder,36 anxiety,20 and obesity.37 Games have been shown to be effective in changing health-related behaviors such as dietary habits,38 smoking cessation,39 exercise,40–43 medication adherence, and others,21, 44–48 and recent reviews of video games, board games and card games have shown promising results within a variety of fields of healthcare. Our study adds to this growing literature by demonstrating that a conversation card game motivates participants engage in an unpopular health behavior, namely discussing death and dying.

Our study is not without limitations. First, convenience samples always introduce the possibility of selection bias that might impact the rates with which participants completed ACP behaviors. Second, because our sample population consisted of highly educated, Caucasian individuals, and we did not record cultural factors in our demographic survey, our results may not be generalizable to more diverse populations. Third, because this study was an exploratory pilot study with no control group, its finding that a conversation game increases the rates of ACP behaviors requires confirmation in a randomized controlled trial before they can be asserted with any real confidence. Additionally, in an effort to maximize participation and retention of individuals in the study, participants received stipends that may have increased participants’ motivation to participate in the study. That said, participants were blind to the study outcomes in order to minimize the impact of the incentive. Finally, though we used both qualitative and quantitative measures to determine the rates of ACP behaviors, data on ACP behaviors were based on participant self-report, which may introduce recall and/or social desirability bias.

Despite these limitations, the present findings contribute to our knowledge of how clinicians, researchers, healthcare providers, and advocates of ACP can motivate individuals to engage in conversations about end-of-life issues. Our findings also suggest there is value in continuing to evaluate and develop game based interventions to enhance engagement in ACP activities. Future studies will test the game intervention in a randomized controlled trial and evaluate the quality of end-of-life conversations that result from playing the game.

CONCLUSION

Individuals who played a conversation game had a high rate of performing ACP behaviors three months after the intervention. These findings suggest that games that may be useful tools for motivating people to engage in ACP behaviors such as discussing end-of-life issues and completing advance directives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All individuals who contributed significantly to this work have been included as authors and have The authors would like to thank XXX for assistance with initial project development, institutional review board approval, and review of the manuscript.

Funding Sources:

This study was funded in part by the Pennsylvania State University Social Sciences Research Institute and the Penn State College of Medicine. Dr. Van Scoy receives funding from the Parker B. Francis Career Development Award from the Francis Family Foundation.

Sponsor’s Role

This study was funded in part by the XX. XX receives funding from the Parker B. Francis Family Foundation. The funders had no role in design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The conversation game “My Gift of Grace” was designed and is sold by an independent company, Common Practice. XXX is an unpaid research advisor to Common Practice, which waived the licensing fee required for use of Intellectual Property for the purposes of this research. However, the authors have no financial relationships with Common Practice to disclose, and Common Practice was not involved in the development, implementation, analysis, or publication of this research. The funders of this research have no relationships with Common Practice or others related to this research to disclose.

Author Contributions:

All authors contributed substantially to this work. This study was conceptualized and designed by authors XXX. Data was collected by authors XXX. Data was analyzed XXX. Data was interpreted by all authors. The manuscript was prepared and reviewed by all authors.

Prior presentations of this work include:

Preliminary results from this study were presented at the 2015 American Thoracic Society Meeting in Denver, Colorado and the 2015 American Society for Bioethics and Humanities meeting in Houston, Texas.

REFERENCES

- [1].Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, O’Leary JR. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57: 1547–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340: 1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Silveira MJ, Kim SH, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362: 1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Scott A Communication about end-of-life health decisions. Communication Yearbook. 2014;38: 242–277. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, et al. Effect of a disease-specific planning intervention on surrogate understanding of patient goals for future medical treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58: 1233–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Morrison RS, Chichin E, Carter J, et al. The effect of a social work intervention to enhance advance care planning documentation in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53: 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin FC, et al. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46: 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Greenberg MR, Weiner M, Greenberg GB. Risk-reducing legal documents: controlling personal health and financial resources. Risk Anal, 2009;29: 1578–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hopp FP. Preferences for surrogate decision makers, informal communication, and advance directives among community-dwelling elders: results from a national study Gerontologist, Volume 40, 2000, pp. 449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Berger JT. What about process? Limitations in advance directives, care planning, and noncapacitated decision making. The American journal of bioethics, 2010; 10: 33–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, et al. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2009; 57: 1547–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57: 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Morrison RS, Morrison EW, Glickman DF. Physician Reluctance to Discuss Advance DirectivesAn Empiric Investigation of Potential Barriers Arch Intern Med, Volume 154: American Medical Association, 1994, pp. 2311–2318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Momen NC, Barclay SI. Addressing ‘the elephant on the table’: barriers to end of life care conversations in heart failure - a literature review and narrative synthesis. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care. 2011;5: 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Prendergast TJ. Advance care planning: pitfalls, progress, promise. Crit Care Med, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Slort W, Schweitzer BP, Blankenstein AH, et al. Perceived barriers and facilitators for general practitioner-patient communication in palliative care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2011;25: 613–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Winzelberg GS, Hanson LC, Tulsky JA. Beyond autonomy: diversifying end-of-life decision-making approaches to serve patients and families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53: 1046–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].DeSmet A, Shegog R, Van R, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Interventions for Sexual Health Promotion Involving Serious Digital Games. Games for Health Journal. 2015;4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wiener L, Battles H, Mamalian C, et al. ShopTalk: a pilot study of the feasibility and utility of a therapeutic board game for youth living with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19: 1049–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Piercey CD, Charlton K, Callewaert C. Reducing Anxiety Using Self-Help Virtual Reality Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Games for Health Journal. 2012;1: 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kharrazi H, Lu AS, Gharghabi F, et al. A Scoping Review of Health Game Research: Past, Present, and Future. Games Health J. 2012;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Van Scoy LJ, Reading JM, Scott AM, et al. Conversation game effectively engages groups of individuals in discussions about death and dying: a feasibility study. J Palliat Med. 2016. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12: 38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jezewski MA, Meeker MA, Sessanna L, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to increase advance directive completion rates. J Aging Health. 2007;19: 519–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mastellos N, Gunn LH, Felix LM, et al. Transtheoretical model stages of change for dietary and physical exercise modification in weight loss management for overweight and obese adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014;2: CD008066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhu LX, Ho SC, Sit JW, et al. The effects of a transtheoretical model-based exercise stage-matched intervention on exercise behavior in patients with coronary heart disease: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95: 384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Finnell DS, Wu YW, Jezewski MA, et al. Applying the transtheoretical model to health care proxy completion. Med Decis Making. 2011;31: 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Aveyard P, Cheng KK, Almond J, et al. Cluster randomised controlled trial of expert system based on the transtheoretical (“stages of change”) model for smoking prevention and cessation in schools. BMJ. 1999;319: 948–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fried TR, Redding CA, Robbins ML, et al. Promoting advance care planning as health behavior change: development of scales to assess Decisional Balance, Medical and Religious Beliefs, and Processes of Change. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86: 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fried TR, Redding CA, Robbins ML, et al. Stages of change for the component behaviors of advance care planning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58: 2329–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Van Scoy LJ, Scott AM, Reading J, et al. An end-of-life conversation game: assessing content and quality of communication. American Sociatey of Bioethics and Humanities; Houston, Texas, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Van Scoy L, Reading JM, Scott AM, et al. Measuring of the quality of end-of-life discussions stimulated by a conversation game using a multiple goals conceptual framework. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society International Conference Denver, Colorado, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med, 2010; 153: 256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hammes BJ, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD. A comparative, retrospective, observational study of the prevalence, availability, and specificity of advance care plans in a county that implemented an advance care planning microsystem. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58: 1249–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bomba P, Kemp M, Black J. POLST: An improvement over traditional advance directives. Cleve Clin J Med, 2012; 79: 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Albright G, Goldman R, Shockley KM, et al. Using an Avatar-Based Simulation to Train Families to Motivate Veterans with Post-Deployment Stress to Seek Help at the VA. Games for Health Journal. 2011;1: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lu AS, Thompson D, Baranowski J, et al. Story Immersion in a Health Videogame for Childhood Obesity Prevention. Games Health J. 2012;1: 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kamada M, Moriyama M, Iwai K. A New Program for Healthy Eating Study Using a Card Game. Games for Health Journal. 2013;2: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Prezzemolo R, et al. Impact of a board-game approach on current smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy. 2013;8: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kayama H, Okamoto K, Nishiguchi S, et al. Efficacy of an Exercise Game Based on Kinect in Improving Physical Performances of Fall Risk Factors in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Games for Health Journal. 2013;2: 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Maloney AE, Stempel A, Wood ME, et al. Can Dance Exergames Boost Physical Activity as a School-Based Intervention? Games for Health Journal. 2012;1: 416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Natbony LR, Zimmer A, Ivanco LS, Studenski SA, Jain S. Perceptions of a Videogame-Based Dance Exercise Program Among Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. Games for Health Journal. 2013;2: 235–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Orsega-Smith E, Davis J, Slavish K, et al. Wii Fit Balance Intervention in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Games for Health Journal. 2012;1: 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Baranowski MT, Fiellin PE, Gay G, et al. Using What’s Learned in the Game for Use in Real Life. Games for Health Journal. 2014;3: 6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kato PM. Video games in health care: Closing the gap. Rev Gen Psychol. 2010;14: 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rahmani E, Boren SA. Videogames and Health Improvement: A Literature Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Games for Health Journal. 2012;1: 331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Read JL, Shortell SM. Interactive games to promote behavior change in prevention and treatment. JAMA. 2011;305: 1704–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]