Abstract

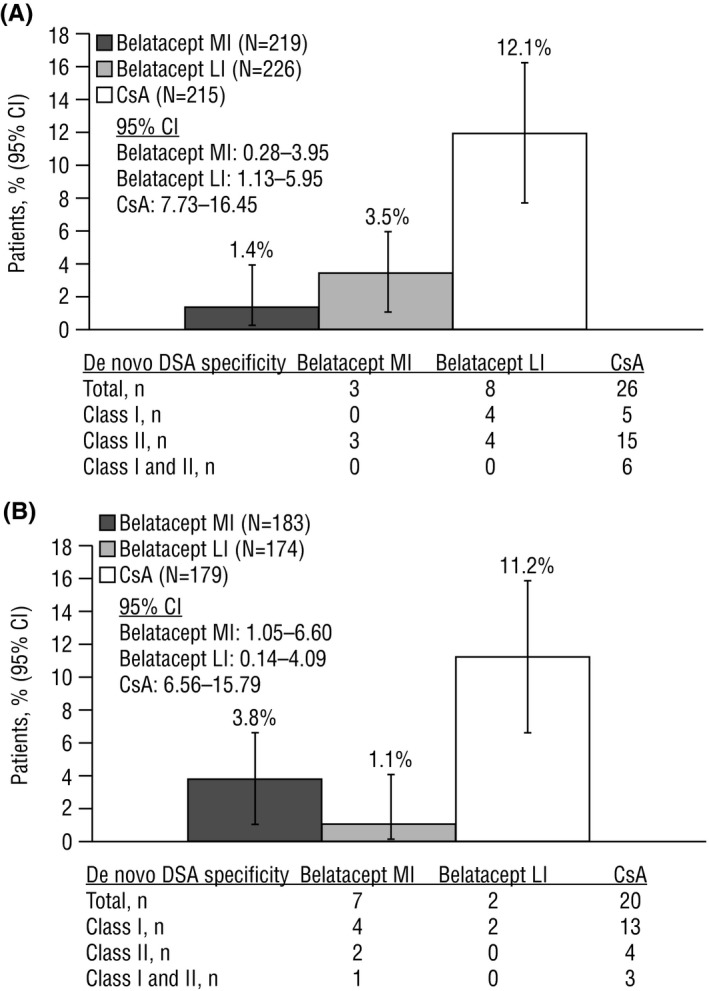

Donor‐specific antibodies (DSAs) are associated with an increased risk of antibody‐mediated rejection and graft failure. In BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT, kidney‐transplant recipients were randomized to receive belatacept more intense (MI)–based, belatacept less intense (LI)–based, or cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression for up to 7 years (84 months). The presence/absence of HLA‐specific antibodies was determined at baseline, at months 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 84, and at the time of clinically suspected episodes of acute rejection, using solid‐phase flow‐cytometry screening. Samples from anti‐HLA‐positive patients were further tested with a single‐antigen bead assay to determine antibody specificities, presence/absence of DSAs, and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of any DSAs present. In BENEFIT, de novo DSAs developed in 1.4%, 3.5%, and 12.1% of belatacept MI‐treated, belatacept LI‐treated, and cyclosporine‐treated patients, respectively. The corresponding values in BENEFIT‐EXT were 3.8%, 1.1%, and 11.2%. Per Kaplan‐Meier analysis, de novo DSA incidence was significantly lower in belatacept‐treated vs cyclosporine‐treated patients over 7 years in both studies (P < .01). In patients who developed de novo DSAs, belatacept‐based immunosuppression was associated with numerically lower MFI vs cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression. Although derived post hoc, these data suggest that belatacept‐based immunosuppression suppresses de novo DSA development more effectively than cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression.

Keywords: antibody biology, belatacept, clinical research/practice, clinical trial, cyclosporin A (CsA), immunosuppressant ‐ calcineurin inhibitor, immunosuppressant ‐ fusion proteins and monoclonal antibodies, kidney transplantation/nephrology

Short abstract

At 7 years posttransplant, patients treated with belatacept exhibit a lower incidence of de novo donor‐specific HLA antibody compared to recipients treated with cyclosporine.

Abbreviations

- BENEFIT

Belatacept Evaluation of Nephroprotection and Efficacy as First‐Line Immunosuppression Trial

- BENEFIT‐EXT

BENEFIT‐Extended Criteria Donors Trial

- CI

confidence interval

- CsA

cyclosporine

- DSA

donor‐specific antibody

- ESRD

end‐stage renal disease

- HR

hazard ratio

- LI

less intense

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MI

more intense

- PRA

panel reactive antibody

1. INTRODUCTION

Belatacept, a selective T cell costimulation blocker, is approved in the United States, the European Union, and other countries for preventing organ rejection in kidney‐transplant recipients aged ≥18 years.1 Belatacept was investigated in 2 randomized phase III studies: Belatacept Evaluation of Nephroprotection and Efficacy as First‐Line Immunosuppression Trial (BENEFIT) and BENEFIT‐Extended Criteria Donors (BENEFIT‐EXT). In these studies, patients were de novo recipients of a living or standard criteria deceased donor kidney (BENEFIT) or an extended criteria donor kidney (BENEFIT‐EXT) and randomized to receive up to 7 years of treatment with belatacept more‐intense (MI)–based, belatacept less‐intense (LI)–based, or cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression.2, 3 In an intent‐to‐treat analysis of BENEFIT undertaken at 7 years posttransplant, belatacept‐based immunosuppression was associated with a 43% reduction in the risk of death or graft loss relative to cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression (belatacept more intensive (MI) vs cyclosporine: hazard ratio [HR] 0.57, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.35–0.95, P = .02; belatacept LI vs cyclosporine: HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.35–0.94, P = .02).4 The risk of death or graft loss in belatacept‐treated and cyclosporine‐treated patients enrolled in BENEFIT‐EXT was similar (belatacept MI vs cyclosporine: HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.63–1.34, P = .65; belatacept LI vs cyclosporine: HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.63–1.36, P = .70).5 Estimated GFR was significantly higher in belatacept‐treated vs cyclosporine‐treated patients over 7 years of follow‐up in both studies.4, 5 No new safety signals emerged with longer duration of exposure to belatacept.4, 5

In kidney‐transplant recipients, the presence of donor‐specific antibodies (DSAs) is associated with an increased risk of antibody‐mediated rejection and graft failure.6 Approximately 11% of kidney‐transplant recipients develop de novo DSAs within the first year after transplantation; this proportion increases to 20% by 5 years posttransplant.7 The risk of antibody‐mediated rejection and graft loss increases with higher mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), a semi‐quantitative measure of the number of DSAs circulating in patient sera.8

On‐treatment analyses of data from BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT showed the Kaplan‐Meier cumulative event rates for de novo DSA development at 7 years posttransplant to be significantly lower with belatacept‐based vs cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression.4, 5 In this updated analysis, MFI was also quantified in the subsets of patients from BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT who developed de novo DSAs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

BENEFIT (NCT00256750) and BENEFIT‐EXT (NCT00114777) were 3‐year, international, partially blinded, active‐controlled, parallel‐group, randomized phase III studies.4, 5 Patients in BENEFIT were transplanted with a living or standard criterion deceased‐donor kidney. Patients in BENEFIT‐EXT were transplanted with an extended criteria donor kidney, which was defined as those meeting United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) expanded donor criteria, those with an anticipated cold ischemia time ≥24 hours, or those donated after circulatory death. All patients in BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT were initially randomized (1:1:1) to receive belatacept MI–based, belatacept LI–based, or cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression for 3 years. Following a protocol amendment, patients were allowed to continue the study treatment to which they had been randomized beyond 3 years, if approved by the treating physician and if the patient provided additional written informed consent.9, 10 In addition to randomized treatment, all study participants received basiliximab induction, mycophenolate mofetil, and corticosteroids.

BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review boards/ethics committees at participating centers approved the study protocols. All patients provided written informed consent.

2.2. Assessments

The presence of HLA antibodies was assessed in all randomized, transplanted patients at baseline, at months 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 84, and at the time of any clinically suspected episodes of acute rejection. Antibody screening was performed centrally at Emory University using solid‐phase flow cytometry screening (FlowPRA, One Lambda, Inc., Canoga Park, CA). Mismatch was determined by comparing donor‐recipient phenotype at the antigen/allele‐level. Sera from patients with anti‐HLA antibodies were subsequently analyzed using LABScreen single‐antigen bead assay (One Lambda, Inc.) to determine antibody class specificity (I or II), the presence/absence of DSAs, and the MFI of any DSAs that were present. A patient was considered de novo DSA‐positive if DSAs developed posttransplant (on‐treatment or within 60 days of discontinuation of study treatment). Antibody specificities with MFI ≥2000 were scored as positive; specificities with MFI <2000 were scored as negative. Sera were not pretreated or diluted prior to single‐antigen bead testing. To minimize variation due to lot/technician differences, all samples—irrespective of the time at which they were drawn—were tested and analyzed at the same time. Single‐antigen bead testing was performed using a modified technique employing a biotin‐conjugated secondary antibody followed by phycoerythrin‐conjugated streptavidin. An MFI value of 2000 in this assay corresponds to a slightly lower MFI value than in the non‐modified assay. Details on our modified technique are described.11

2.3. Statistics

Analyses were performed on the intent‐to‐treat population. The absolute proportion of patients who developed de novo DSAs by year 7 (month 84) was calculated for each study. The cumulative incidence of de novo DSAs was analyzed separately for BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT and summarized using Kaplan‐Meier curves and event rates. HRs and 95% CIs at month 84 were calculated via Cox regression. MFI in the subset of patients from each study who developed de novo DSAs was summarized using descriptive statistics.

3. RESULTS

3.1. BENEFIT

At 7 years posttransplant, 1.4% (3/219) of belatacept MI‐treated, 3.5% (8/226) of belatacept LI‐treated, and 12.1% (26/215) of cyclosporine‐treated patients developed de novo DSAs (Figure 1A). All 3 belatacept MI‐treated patients developed de novo DSAs with class II HLA specificity. Of the 8 belatacept LI‐treated patients who developed de novo DSAs, class I HLA specificity was detected in 4 patients; the remaining 4 patients developed de novo DSAs with class II HLA specificity. Among cyclosporine‐treated patients, 5 developed de novo DSAs with class I HLA specificity, 15 with class II HLA specificity, and 6 with both class I and class II HLA specificity. De novo DSAs developed most frequently against the HLA‐DQ locus in all treatment arms (belatacept MI 100.0% [3/3], belatacept LI 50.0% [4/8], cyclosporine 69.2% [18/26]) arms (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Absolute percentage of patients who developed de novo DSAs by month 84 in (A) BENEFIT and (B) BENEFIT‐EXT. CI, confidence interval; CsA, cyclosporine; DSA, donor‐specific antibody; LI, less intense; MI, more intense

Table 1.

Specificity of de novo DSAs by HLA locus

| BENEFIT | BENEFIT‐EXT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belatacept MI (n = 3) | Belatacept LI (n = 8) | Cyclosporine (n = 26) | Belatacept Ml (n = 7) | Belatacept LI (n = 2) | Cyclosporine (n = 20) | |

| Class 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 13 |

| A | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| B | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| C | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| A and B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| A, B, and C | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Class II | 3 | 4 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| DR | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| DP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DQ | 3 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| DR and DQ | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Class 1 and II | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| A and DR | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| A, B, and DR | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| A, B, DR, and DQ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A, C, and DQ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A and DQ | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B and DR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Data are number of patients. DSA, donor‐specific antibody; LI, less intense; Ml, more intense.

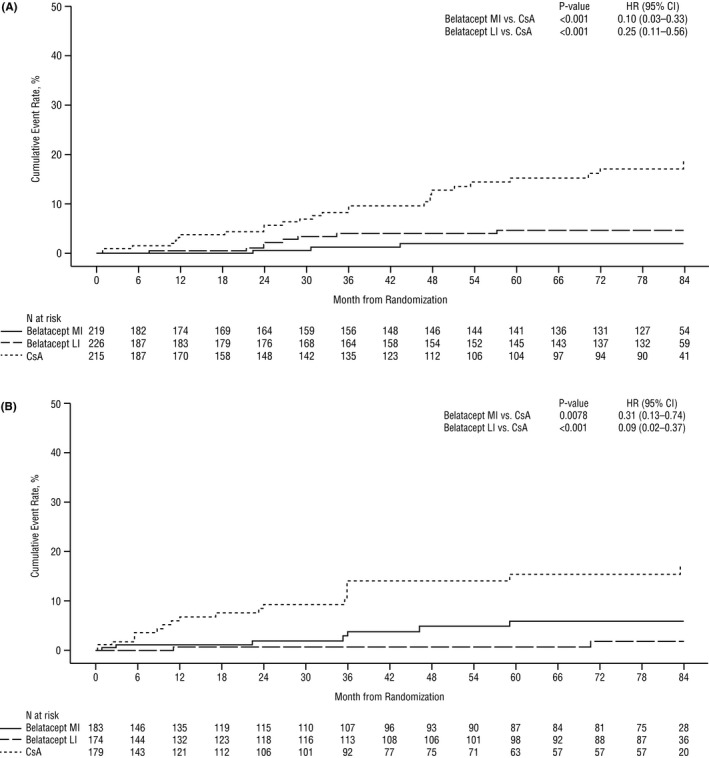

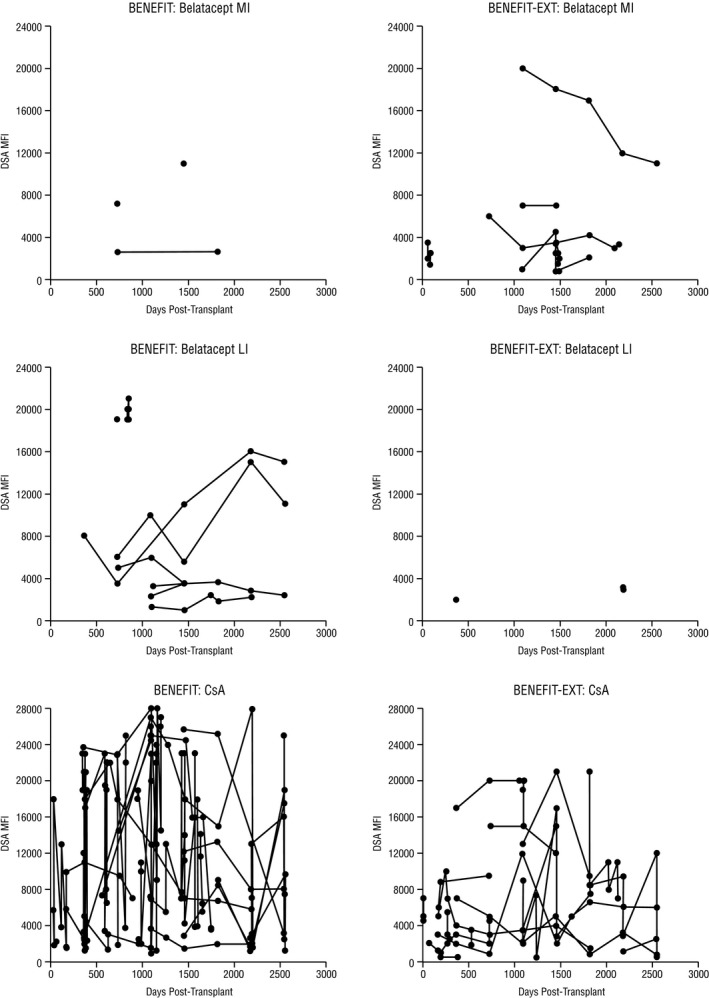

The cumulative event rates of de novo DSAs at month 84 for belatacept MI‐treated, belatacept LI‐treated, and cyclosporine‐treated patients were 1.9%, 4.6%, and 18.9%, respectively. The HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with cyclosporine was 0.10 (95% CI 0.03–0.33, P < .001), and the HR for the comparison of belatacept LI with cyclosporine was 0.25 (95% CI 0.11–0.56, P < .001) (Figure 2A). Proportionally fewer belatacept‐treated vs cyclosporine‐treated patients who developed de novo DSAs had MFI >10 000 (belatacept MI 33.3% [1/3]; belatacept LI 50.0% [4/8]; cyclosporine 76.9% [20/26]) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan‐Meier analysis of the cumulative rate of de novo DSA development in (A) BENEFIT and (B) BENEFIT‐EXT. CI, confidence interval; CsA, cyclosporine; DSA, donor‐specific antibody; HR, hazard ratio; LI, less intense; MI, more intense

Figure 3.

MFI in the subset of patients in BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT who developed de novo DSAs. CsA, cyclosporine; DSA, donor‐specific antibody; LI, less intense; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; MI, more intense

Across the 3 treatment arms, 37 patients developed de novo DSAs and 623 did not. Baseline characteristics were generally similar between patients who did and did not develop de novo DSAs, but a numerically greater percentage of de novo DSA‐positive patients had categorized panel‐reactive antibody <20% (97.3% vs 86.4%) and 6 HLA mismatches (16.2% vs 8.5%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics in the subgroups of patients who did and did not develop DSAs

| BENEFIT | BENEFIT‐EXT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De novo DSA‐positive (n = 37) | De novo DSA‐negative (n = 623) | De novo DSA‐positive (n = 29) | De novo DSA‐negative (n = 507) | |

| Mean age, y (SD) | 35.4 (13.3) | 43.7 (14.0) | 53.7 (11.7) | 56.3 (12.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 26 (70.3) | 432 (69.3) | 15 (51.7) | 343 (67.7) |

| Region | ||||

| North America | 22 (59.5) | 269 (43.2) | 6 (20.7) | 130 (25.6) |

| South America | 1 (2.7) | 101 (16.2) | 12 (41.4) | 129 (25.4) |

| Europe | 9 (24.3) | 155 (24.9) | 11 (37.9) | 245 (48.3) |

| Rest of world | 5 (13.5) | 98 (15.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.6) |

| Categorized PRA, n (%) | ||||

| <20% | 36 (97.3) | 538 (86.4) | 26 (89.7) | 477 (94.1) |

| ≥20% | 1 (2.7) | 70 (11.2) | 0 (0) | 7 (1.4) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 15 (2.4) | 3 (10.3) | 23 (4.5) |

| Reported cause of ESRD, n (%) | ||||

| Glomerular disease | 15 (40.5) | 161 (25.8) | 6 (20.7) | 113 (22.3) |

| Diabetes | 3 (8.1) | 75 (12.0) | 4 (13.8) | 76 (15.0) |

| Polycystic kidneys | 2 (5.4) | 89 (14.3) | 4 (13.8) | 91 (17.9) |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 3 (8.1) | 59 (9.5) | 4 (13.8) | 90 (17.8) |

| Renovascular and other vascular diseases | 0 (0.0) | 12 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (2.0) |

| Congenital, rare familial, and metabolic | 0 (0) | 23 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.2) |

| Disorders | ||||

| Tubular and interstitial diseases | 1 (2.7) | 33 (5.3) | 3 (10.3) | 26 (5.1) |

| Re‐transplant/graft failure | 0 (0) | 7 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 13 (35.1) | 164 (26.3) | 8 (27.6) | 95 (18.7) |

| HLA mismatches, n (%) | ||||

| 4 | 7 (18.9) | 127 (20.4) | 8 (27.6) | 132 (26.0) |

| 5 | 7 (18.9) | 70 (11.2) | 5 (17.2) | 100 (19.7) |

| 6 | 6 (16.2) | 53 (8.5) | 4 (13.8) | 34 (6.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 17 (2.7) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0) |

DSA, donor‐specific antibody; ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; LI, less intense; MI, more intense; PRA, panel reactive antibody; SD, standard deviation.

3.2. BENEFIT‐EXT

At 7 years posttransplant, 3.8% (7/183) of belatacept MI‐treated, 1.1% (2/174) of belatacept LI‐treated, and 11.2% (20/179) of cyclosporine‐treated patients developed de novo DSAs (Figure 1B). Among belatacept MI‐treated patients, 4 developed de novo DSAs with class I HLA specificity, 2 with class II HLA specificity, and 1 with both class I and class II HLA specificity. Both belatacept LI‐treated patients developed de novo DSAs with class I HLA specificity. Among cyclosporine‐treated patients, 13 developed de novo DSAs with class I HLA specificity, 4 with class II HLA specificity, and 3 with both class I and class II HLA specificity. The HLA loci against which de novo DSAs developed are summarized in Table 1.

The cumulative event rates of de novo DSAs at month 84 for belatacept MI‐treated, belatacept LI‐treated, and cyclosporine‐treated patients were 5.9%, 1.9%, and 17.1%, respectively. The HR for the comparison of belatacept MI with cyclosporine was 0.31 (95% CI 0.13–0.74, P = .0078), and the HR for the comparison of belatacept LI with cyclosporine was 0.09 (95% CI 0.02–0.37, P < .001) (Figure 2B). Proportionally fewer belatacept‐treated vs cyclosporine‐treated patients who developed de novo DSAs had MFI >10 000 (belatacept MI 14.3% [1/7], belatacept LI 0% [0/2], cyclosporine 45.0% [9/20]) (Figure 3).

Across the 3 treatment arms, 29 patients developed de novo DSAs and 507 did not. Baseline characteristics were generally similar between patients who did and did not develop de novo DSAs, but a numerically lower proportion of de novo DSA‐positive patients were male (51.7% vs 67.7%) (Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

The outcomes from this on‐treatment analysis of de novo DSA development in the phase III BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT studies show that belatacept‐based immunosuppression is associated with a significantly lower incidence of de novo DSA development relative to cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression over 7 years (84 months) of follow‐up. These findings are consistent with analyses performed at 3 years posttransplant,12, 13 which suggests that the effects of belatacept on preventing de novo DSA development are sustained over time. In the subset of patients in BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT who developed de novo DSAs, belatacept‐based treatment appeared to result in lower antibody titers compared with cyclosporine‐based treatment. Of note, 76.9% (20/26) of cyclosporine‐treated patients who developed de novo DSAs had either class II HLA‐DR and/or HLA‐DQ mismatches. In the subset of belatacept‐treated patients (MI or LI) who developed de novo DSAs, 63.6% (7/11) were HLA‐DQ mismatched, but none had a HLA‐DR mismatch. These data suggest an intriguing biological relationship between class II HLA‐DQ mismatching and de novo DSA production that will need to be addressed in subsequent studies.

Due to the post hoc nature of these analyses and small sizes, these results should be interpreted with caution. In addition to these limitations, the inability to detect DSAs immediately prior to transplant does not prove that all DSAs measured posttransplant were de novo; pretransplant/preexisting DSAs could have been present at levels below the sensitivity of the assays used or have resulted from a memory response. Despite these caveats, these preliminary results suggest that belatacept‐based immunosuppression prevents de novo DSA development more effectively than cyclosporine‐based immunosuppression.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation. M. Roberts, M. Polinsky, and L. Yang are salaried employees of and own stock in Bristol‐Myers Squibb. R. Townsend and H.‐U. Meier‐Kriesche were salaried employees of Bristol‐Myers Squibb at the time that these analyses undertaken and still own stock in Bristol‐Myers Squibb. C. P. Larsen has received grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb. R. Bray and H. Gebel have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT studies were sponsored by Bristol‐Myers Squibb. Support for third‐party writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by Tiffany DeSimone, PhD, of CodonMedical, an Ashfield Company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, and was funded by Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

Bray RA, Gebel HM, Townsend R, et al. De novo donor‐specific antibodies in belatacept‐treated vs cyclosporine‐treated kidney‐transplant recipients: Post hoc analyses of the randomized phase III BENEFIT and BENEFIT‐EXT studies. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:1783–1789. 10.1111/ajt.14721

REFERENCES

- 1. Squibb Bristol‐Myers . Belatacept (NULOJIX) Prescribing Information. Princeton, NJ: Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vincenti F, Charpentier B, Vanrenterghem Y, et al. A phase III study of belatacept‐based immunosuppression regimens vs cyclosporine in renal transplant recipients (BENEFIT study). Am J Transplant. 2010;10:535‐546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Durrbach A, Pestana JM, Pearson T, et al. A phase III study of belatacept vs cyclosporine in kidney transplants from extended criteria donors (BENEFIT‐EXT study). Am J Transplant. 2010;10:547‐557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vincenti F, Rostaing L, Grinyo J, et al. Belatacept and long‐term outcomes in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:333‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durrbach A, Pestana JM, Florman S, et al. Long‐term outcomes in belatacept‐ vs cyclosporine‐treated recipients of extended criteria donor kidneys: final results from BENEFIT‐EXT, a phase III randomized study. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:3192‐3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mohan S, Palanisamy A, Tsapepas D, et al. Donor‐specific antibodies adversely affect kidney allograft outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:2061‐2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Everly MJ, Rebellato LM, Haisch CE, et al. Incidence and impact of de novo donor‐specific alloantibody in primary renal allografts. Transplantation. 2013;95:410‐417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lefaucheur C, Loupy A, Hill GS, et al. Preexisting donor‐specific HLA antibodies predict outcome in kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1398‐1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rostaing L, Vincenti F, Grinyó J, et al. Long‐term belatacept exposure maintains efficacy and safety at 5 years: results from the long‐term extension of the BENEFIT study. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2875‐2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charpentier B, Medina Pestana JO, Del C Rial M, et al. Long‐term exposure to belatacept in recipients of extended criteria donor kidneys. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2884‐2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sullivan HC, Gebel HM, Bray RA. Understanding solid‐phase HLA antibody assays and the value of MFI. Hum Immunol. 2017;78:471‐480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vincenti F, Larsen CP, Alberu J, et al. Three‐year outcomes from BENEFIT, a randomized, active‐controlled, parallel‐group study in adult kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(1):210‐217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pestana JO, Grinyo JM, Vanrenterghem Y, et al. Three‐year outcomes from BENEFIT‐EXT: a phase III study of belatacept vs cyclosporine in recipients of extended criteria donor kidneys. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:630‐639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]