Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor α (PPARα) is a key transcriptional factor that regulates hepatic lipid catabolism by stimulating fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis in an adaptive response to nutrient starvation. However, how PPARα is regulated by posttranslational modification is poorly understood. In this study, we identified that progestin and adipoQ receptor 3 (PAQR3) promotes PPARα ubiquitination through the E3 ubiquitin ligase HUWE1, thereby negatively modulating PPARα functions both in vitro and in vivo. Adenovirus‐mediated Paqr3 knockdown and liver‐specific deletion of the Paqr3 gene reduced hepatic triglyceride levels while increasing fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis upon fasting. PAQR3 deficiency enhanced the fasting‐induced expression of PPARα target genes, including those involved in fatty acid oxidation and fibroblast growth factor 21, a key molecule that mediates the metabolism‐modulating effects of PPARα. PAQR3 directly interacted with PPARα and increased the polyubiquitination and proteasome‐mediated degradation of PPARα. Furthermore, the E3 ubiquitin ligase HUWE1 was identified to mediate PPARα polyubiquitination. Additionally, PAQR3 enhanced the interaction between HUWE1 and PPARα. Conclusion: Ubiquitination modification through the coordinated action of PAQR3 with HUWE1 plays a crucial role in regulating the activity of PPARα in response to starvation. (Hepatology 2018;68:289‐303).

Abbreviations

- aa

amino acid

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- FGF21

fibroblast growth factor 21

- GST

glutathione‐S‐transferase

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- NEFA

nonesterified fatty acid

- NFκB

nuclear factor κB

- PAQR

progestin and adipoQ receptor

- PPARα

peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor α

- RT‐PCR

reverse‐transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SD

standard deviation

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- TG

triglyceride

The liver is the central metabolic organ that regulates several key aspects of lipid metabolism, including fatty acid β‐oxidation, lipogenesis, lipoprotein uptake, and secretion in response to nutritional and hormonal signals. For example, fed and fasting conditions are the two most important ways to change hormone secretion and modulate anabolism and catabolism in the body. In the fed state, increased glucose levels stimulate insulin secretion, which is a driving force to stimulate anabolic reactions, such as increased glycogen synthesis and lipogenesis. In contrast, fasting is a driving force for catabolism through the stimulation of fatty acid oxidation and autophagy. Hepatic fatty acid oxidation can also generate ketone bodies that progressively become the predominant energy source for the brain during long‐term fasting. Dysregulation of lipid metabolic pathways in the liver results in the development of hepatic steatosis and contributes to the development of chronic hepatic inflammation, insulin resistance, and liver damage.1, 2, 3

The integrated transcriptional regulatory networks that are governed at the transcriptional level by transcription factors and cofactors enable an organism to adapt its metabolic state to different nutrient conditions.4, 5, 6 The key regulatory factors responding to diet‐derived bioactive lipids are represented by a group of adopted orphan nuclear receptors that includes peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor (PPAR), retinoid X receptor, liver X receptor, and farnesoid X receptor.7 Among these nuclear receptors, PPARs, which consist of PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARβ/δ, mainly function as integrators of inflammatory and metabolic signaling networks and have been extensively targeted for the treatment of metabolic disorders.8 PPARα is expressed predominantly in the liver, where it plays a crucial role in modulating lipid metabolism in response to fasting. PPARα is robustly induced upon fasting and PPARα activation promotes the hepatic transcription of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, fatty acid transport, and ketogenesis.8 PPARγ is highly expressed in adipose tissues and regulates various functions in adipocytes. PPARβ/δ is mainly expressed in skeletal muscles and plays a functional role in the response to exercise. PPARs form heterodimers with retinoid X receptor, followed by binding to specific DNA‐response elements in target genes known as peroxisome proliferator response elements. PPARα is indispensable for maintaining lipid homeostasis in the liver, as PPARα‐null mice are unable to meet energy demands during fasting and suffer from hypoglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hypoketonemia, and fatty liver.9, 10 PPARα overexpression or activation by specific PPARα agonists lowers plasma triglycerides, reduces adiposity, and improves hepatic steatosis, consequently improving insulin sensitivity.11, 12, 13

Recent studies have provocatively suggested that posttranslational modifications can be found on all three PPAR isoforms.14 For example, several E3 ubiquitin ligases have been reported to participate in the polyubiquitination of PPARγ during adipocyte differentiation.15, 16, 17 Additionally, PPARγ itself acts as an E3 ligase to induce the degradation of nuclear factor κB (NFκB)/p65 and inhibit NFκB‐mediated inflammatory responses and xenograft tumor growth.18 It was reported recently that monoubiquitination of PPARα by the ubiquitin ligase MuRF1 is able to regulate PPARα nuclear export in the heart in a proteasome‐independent manner.19 Moreover, MDM2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, is also able to interact with PPARα to modulate its transcriptional activity at the cellular level.20 However, how PPARα is regulated by polyubiquitination and proteasome‐mediated degradation remains unknown.

HUWE1 (also named ARF‐BP1, HectH9, LASU1, Mule, and Ureb1) is a large protein (∼500 kDa) whose function is not fully understood. HUWE1 belongs to the HECT‐domain family of ubiquitin ligases, which are characterized by a conserved carboxyl‐terminal catalytic domain.21 HUWE1 has been reported to act as an E3 ligase to regulate the degradation of many proteins involved in various biological functions. In particular, HUWE1 directly binds to and ubiquitinates p53 and subsequently promotes cell growth in a p53/Mdm2‐independent manner.22 HUWE1 can also control neural differentiation and proliferation by destabilizing the oncoprotein N‐Myc.23 Additionally, HUWE1 plays an important role in regulating apoptosis via polyubiquitination of Mcl‐1.24 HUWE1 can also function as a tumor suppressor to inhibit tumor cell proliferation and is also implicated in other biological functions such as protein homeostasis and mitochondrial integrity.25, 26 HUWE1 also regulates mitochondrial morphology and function.27 It maintains cellular homeostasis as a quality control system that degrades unassembled ribosomal proteins.28 It also regulates the Wnt signaling pathway to impact intestinal stem cell niches.29 However, whether HUWE1 is involved in metabolism regulation in the liver has been elusive.

Progestin and adipoQ receptor 3 (PAQR3) is a member of the PAQR superfamily and displays the characteristic seven transmembrane helices.30, 31 Previous studies have revealed that PAQR3 acts as a tumor suppressor to regulate tumor cell proliferation and migration by negatively regulating Raf kinases and AKT activation.30, 32, 33, 34, 35 Further studies have demonstrated that PAQR3 also modulates insulin sensitivity, energy metabolism and obesity in mice partly by negatively regulating class I PI3K.36, 37 PAQR3 can regulate insulin signaling in the liver.36 Deletion of Paqr3 can alleviate hepatic steatosis in mice fed a high‐fat diet.37 Our group recently found that PAQR3 can regulate autophagy by integrating AMPK signaling upon glucose starvation.38 Intriguingly, PAQR3 also regulates anabolism by elevating cholesterol homeostasis by anchoring the Scap/SREBP2 complex to the Golgi apparatus.39 In this study, we demonstrate that PAQR3 is an important regulator of lipid catabolism by regulating PPARα polyubiquitination/degradation, thereby modulating the hepatic functions of PPARα.

Materials and Methods

Additional details regarding the materials and methods used in this study are provided in the http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo.

ANIMALS

Eight‐ to 10‐week‐old male mice with a C57BL/6 background were purchased from Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Inc. (Shanghai, China) and fed a normal chow diet (SLACOM, Shanghai, China). All the mice were kept on a regular chow diet and allowed ad libitum access to food and water on a 12‐hour light/dark cycle. All mice were randomly grouped before any experiments started. For fasting experiments, food was removed for 18 hours. Paqr3 tm1a(KOMP)Wtsi (Strain ID) embryos with C57BL/6 background were ordered and resuscitated in the KOMP Repository (Davis, CA). The mice were then bred with Flp mice to release the flox sites. They were then mated with mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by the albumin promoter (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to generate liver‐specific Paqr3 knockout mice (Paqr3 LKO). PAQR3 LKO mice and their age‐matched littermate Lox controls (Cre−/−, Paqr3flox/flox) were fed ad libitum with a standard laboratory chow diet (SLACOM, Shanghai, China). All animal procedures were performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute for Nutritional Sciences, Shanghai Institute for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

MOUSE PRIMARY HEPATOCYTE ISOLATION, ADENOVIRUS INFECTION, AND INDUCTION OF FATTY ACID OXIDATION

The isolation of mouse primary hepatocytes was completed as described in detail previously.39 Briefly, mouse primary hepatocytes were isolated from male wild‐type control or liver‐specific PAQR3 deletion mice using collagenase perfusion, seeded on collagen‐coated plates in seeding medium (high‐glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM], 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 nM insulin, 1 mM dexamethasone), and maintained in maintenance medium (low‐glucose DMEM, 0.1% fetal bovine serum). For adenovirus infection, mouse primary hepatocytes were isolated from male C57BL/6 wild‐type (WT) mice. At 4 hours after cell attachment, adenovirus was added to the plates by changing the culture medium. To induce the expression of fatty acid oxidation genes, primary hepatocytes were preincubated with 125 μM palmitic acid/bovine serum albumin overnight in the presence or absence of 30 μM WY14643 (Tocris Bioscience, MN) in low‐glucose medium, followed by incubation with 125 μM palmitic acid/bovine serum albumin and 1 mM carnitine in glucose‐free DMEM medium for an additional 4 hours.

ANALYSIS OF PROTEIN UBIQUITINATION

The relevant plasmids were cotransfected into HEK293T cells in 6‐cm dishes using polyetherimide following the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty‐four hours after transfection, cells were washed three times with phosphate‐buffered saline and then lysed with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris‐HCl [pH 7.5], 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% NP‐40, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitor cocktail) for 30 minutes at 4°C. The homogenates were centrifuged for 30 minutes at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. Then, 5% of the supernatant was harvested for immunoblotting as inputs, while the remaining cell lysate was incubated with the indicated antibodies overnight at 4°C. Protein A/G plus agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were added to the supernatants for another 2 hours at 4°C. After extensive washing (6 times) with lysis buffer, the beads were spun down and resuspended with 60 μL 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis buffer, followed by immunoblotting. For the ubiquitination assay, lentivirus‐mediated HEK293T and HepG2 stable cells were transfected with HA–ubiquitin constructs together with the indicated plasmids. Twenty‐four hours after transfection, the cells were treated with or without 10 μM MG132 for an additional 6 hours to block proteasomal degradation of the PPARα protein before being lysed with denaturing lysis buffer as completed before. Pulled down samples were subject to immunoblotting with anti‐HA (ubiquitin) to visualize the polyubiquitinated PPARα protein bands under various conditions.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were performed using an unpaired, two‐tailed Student t test. Analysis of variance was used for more than two groups, and post hoc analysis was performed using Tukey's test.

Results

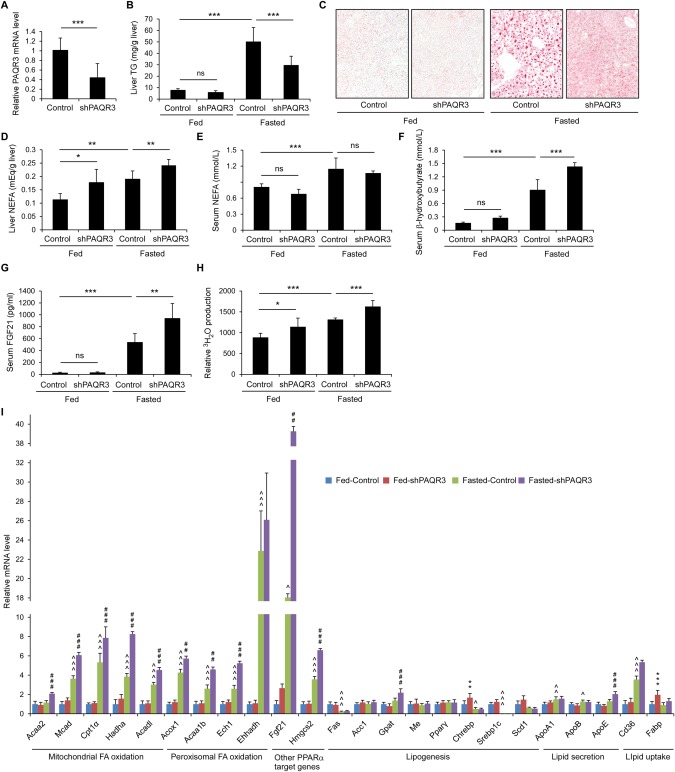

ADENOVIRUS‐MEDIATED KNOCKDOWN OF PAQR3 LOWERS HEPATIC Triglyceride CONTENTS UPON FASTING

To investigate whether PAQR3 participates in hepatic lipid metabolism upon food deprivation, we first examined the effects of Paqr3 knockdown on lipid accumulation in mouse livers under both fed and fasting conditions. We injected C57BL/6 mice with control or PAQR3‐specific short hairpin RNA (shRNA) adenoviruses by way of tail vein injection as described previously.39 Successful silencing of Paqr3 was confirmed by reverse‐transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) using liver samples (Fig. 1A). Liver triglyceride (TG) levels were analyzed in both fed and fasted mice. As expected, fasting was able to robustly elevate liver TG levels (Fig. 1B). Intriguingly, Paqr3 knockdown significantly reduced the fasting‐induced increase in liver TG levels (Fig. 1B). Consistently, Oil Red O staining of the liver samples demonstrated that the Paqr3 knockdown mice exhibited ameliorated hepatic steatosis compared with the control mice under fasting conditions (Fig. 1C). The levels of nonesterified fatty acids (NEFAs) in the liver were also slightly increased by Paqr3 knockdown under both fed and fasted conditions (Fig. 1D). Paqr3 knockdown had minimal effects on serum NEFAs (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Paqr3 knockdown lowers hepatic TG contents and enhances PPARα functions in response to fasting. Male C57BL/6 mice (8‐10 weeks old) were injected with adenovirus containing control shRNAs or PAQR3‐specific shRNAs by way of tail vein injection for 7 days, followed by fasting for 18 hours (n = 8 per group). (A) PAQR3 mRNA levels were measured by quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR. (B) Liver TG levels. (C) Oil Red O staining of liver sections from mice. (D‐G) Other liver and serum parameters including NEFAs (D), serum NEFAs (E), serum β‐hydroxybutyrate (F), and serum FGF21 concentrations (G). (H) Relative rate of fatty acid oxidation in the mouse liver. (I) Quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR analysis of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, lipogenesis, lipid secretion, and lipid uptake in the liver. All data are presented as the mean ± SD. For data shown in panels A‐H: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. ns, not significant. For data shown in panel I: *comparison between fed‐control and fed‐shPAQR3 groups; ∧comparison between fed‐control and fasted‐control groups; #fasted‐control and fasted‐shPAQR3 groups; one symbol for P < 0.05, two symbols for P < 0.01; three symbols for P < 0.001.

As expected, the serum levels of β‐hydroxybutyrate, a marker for fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis in the liver, were robustly elevated by fasting (Fig. 1F). Importantly, Paqr3 knockdown greatly enhanced this elevation (Fig. 1F). Fasting also induced the expression of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) (Fig. 1G), another important molecule that mediates the regulatory functions of PPARα under fasting conditions.40 Consistently, Paqr3 knockdown enhanced the fasting‐induced secretion of FGF21 (Fig. 1G).

REGULATION OF HEPATIC PPARΑ FUNCTION BY PAQR3

The enhancement of β‐hydroxybutyrate and FGF21 by Paqr3 knockdown under fasting conditions led us to speculate that PAQR3 could regulate the function of PPARα, a master regulator of fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis in the liver.9, 10, 41 To test this hypothesis, we investigated the rate of fatty acid oxidation in mouse livers. We found that 3H‐palmitate β‐oxidation was modestly enhanced by Paqr3 knockdown in liver tissue homogenates (Fig. 1H), providing evidence that PPARα‐controlled fatty acid oxidation is indeed modulated by PAQR3.

We next analyzed the effects of Paqr3 knockdown on the expression of PPARα target genes, including those involved in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation. We also analyzed the expression of other genes involved in lipid metabolism, such as those involved in lipogenesis, lipid secretion, and lipid uptake. In general and as expected, fasting could stimulate the expression of most PPARα target genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, including Mcad, Cpt1α, and Acox1 (Fig. 1I). Fasting also slightly stimulated the expression of genes involved in lipid secretion, such as ApoA1 and ApoB, while reducing the expression of a few lipogenic genes, including Fas, Chrebp, and Srebp1c (Fig. 1I). Under fed conditions, Paqr3 knockdown had a minimal effect on the expression of most of the analyzed genes (Fig. 1I). However, Paqr3 knockdown could significantly enhance the fasting‐induced expression of most PPARα target genes, though it had no significant effects on most of the other lipid metabolism‐related genes (Fig. 1I). Collectively, these data are highly indicative that PAQR3 can drastically enhance the expression of PPARα target genes under fasting conditions. These data also indicate that Paqr3 knockdown lowers liver TG levels upon fasting mainly through up‐regulation of the PPARα pathway, but not through its modulation of lipogenesis, lipid uptake, or lipid secretion.

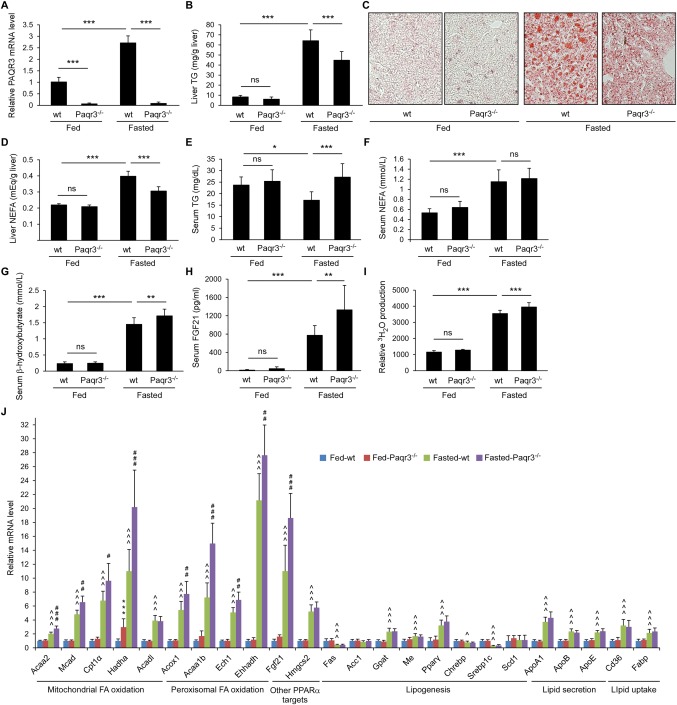

HEPATIC DELETION OF Paqr3 LOWERS HEPATIC TG CONTENTS AND ENHANCES THE EXPRESSION OF PPARΑ TARGET GENES UPON FASTING

To further validate whether PAQR3 participates in hepatic lipid metabolism upon food deprivation, we generated liver‐specific Paqr3 knockout mice (referred to as Paqr3 LKO mice) with a C57BL/6 background using the Cre/loxP system. The successful deletion of Paqr3 in the liver was confirmed by RT‐PCR (Fig. 2A). Although Paqr3 LKO mice were phenotypically normal under a chow diet without a change in their body weight, they had reduced liver TG levels under fasting conditions (Fig. 2B). Consistently, Oil Red O staining demonstrated that Paqr3 LKO mice exhibited ameliorated hepatic steatosis under fasting conditions (Fig. 2C). Liver NEFAs were also decreased by Paqr3 deletion under fasting conditions (Fig. 2D). Serum TG levels were significantly elevated by Paqr3 deletion under fasting conditions (Fig. 2E), with no significant effect on serum NEFAs (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Liver‐specific deletion of Paqr3 elevates PPARα functions. Male mice with a liver‐specific deletion of Paqr3 (Paqr3−/− mice) and age‐matched flox/flox littermates (wt) at 8‐10 weeks old were fed ad libitum or fasted for 18 hours (n = 8 per group). (A) PAQR3 expression levels were measured by way of real‐time RT‐PCR in the liver. (B) Liver TG contents. (C) Oil Red O staining of liver sections from mice. (D‐G) Other liver and serum parameters including NEFAs (D), serum TG (E), serum NEFAs (F), serum β‐hydroxybutyrate (G), and serum FGF21 concentrations (H). (I) Relative rate of fatty acid oxidation in the liver. (J) Quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR analysis of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, lipogenesis, lipid secretion, and lipid uptake in the mouse liver. All data shown above are presented as the mean ± SD. For data shown in panels A‐I: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. ns, not significant. For data shown in panel J: *comparison between fed‐control and fed‐Paqr3−/− groups; ∧comparison between fed‐control and fasted‐control groups; #fasted‐control and fasted‐Paqr3−/− groups; one symbol for P < 0.05, two symbols for P < 0.01, three symbols for P < 0.001.

We next analyzed markers that are regulated by PPARα. We found that serum β‐hydroxybutyrate levels were significantly elevated by Paqr3 deletion under fasting conditions (Fig. 2G). The fasting‐induced secretion of FGF21 into the serum was significantly enhanced by Paqr3 deletion (Fig. 2H). Consistently, the fasting‐induced increase in 3H‐palmitate β‐oxidation was slightly but significantly enhanced by Paqr3 deletion in the liver (Fig. 2I). Furthermore, we found that the fasting‐induced expression of numerous PPARα target genes was enhanced by Paqr3 deletion in the liver (Fig. 2J). Collectively, these data provide additional evidence that PAQR3 can negatively modulate PPARα function in the mouse liver.

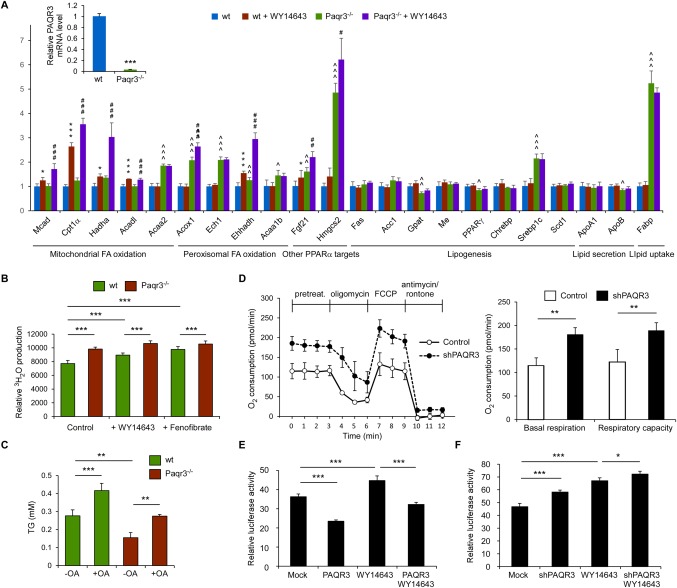

PAQR3 REGULATES PPARΑ FUNCTION IN PRIMARY HEPATOCYTES

We next explored the modulatory effects of PAQR3 on PPARα function at the cellular level. We successfully established primary hepatocytes from wild‐type control or Paqr3 LKO mice. The knockout efficiency of Paqr3 was confirmed by way of RT‐PCR (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the data observed at the animal level (Figs. 1 and 2), deletion of Paqr3 led to increased expression of some PPARα target genes, such as Acaa2, Acox1, Ech1, Ehhadh, and Fgf21 (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, Paqr3 knockout was able to boost the expression of numerous PPARα target genes stimulated by the PPARα agonist WY14643 (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the increase in the expression of fatty acid oxidation‐related genes by PAQR3 deletion, 3H‐palmitate β‐oxidation in Paqr3‐deficient hepatocytes was significantly higher than in control hepatocytes (Fig. 3B). Moreover, Paqr3 knockout could enhance 3H‐palmitate β‐oxidation upon treatment with the PPARα agonists WY14643 or fenofibrate (Fig. 3B). Because fatty acid oxidation is associated with the triglyceride contents in hepatocytes, we used BODIPY to stain the lipid droplets in primary hepatocytes. Paqr3 knockdown significantly reduced lipid droplet accumulation after oleic acid treatment (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo). Consistently, the triglyceride contents were significantly reduced in Paqr3‐deleted hepatocytes (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

PAQR3 regulates PPARα functions in primary hepatocytes. (A) PAQR3 regulates the expression of PPARα target genes in hepatocytes. Primary hepatocytes from wild‐type control or liver‐specific Paqr3 deletion mice were treated with WY14643 (30 μM) as described in the Materials and Methods. The mRNA levels of PAQR3 as well as genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, lipogenesis, lipid secretion, and lipid uptake were measured by way of quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR. (B) PAQR3 modulates fatty acid oxidation in hepatocytes. The cells in panel A were treated with WY14643 (30 μM) or fenofibrate (50 μM) for 24 hours, followed by measurement of the fatty acid oxidation rate. (C) PAQR3 affects lipid accumulation in hepatocytes. The TG concentration was determined in primary hepatocytes as in panel A after incubation with or without oleic acid (OA, 200 μM) for 18 hours. (D) Oxygen consumption is modified by PAQR3. HepG2 cells infected with lentivirus‐containing control shRNAs or PAQR3‐specific shRNAs were analyzed with a Seahorse XF24 extracellular flux analyzer. The basal respiration and respiratory capacity oxygen consumption rates were measured and calculated as averages for each phase. (E, F) PAQR3 regulates ligand‐dependent PPARα transactivation. HepG2 cells that stably expressed ectopic PAQR3 (E) or PAQR3‐shRNA (F) as well as their individual controls through lentiviruses were transiently transfected with the PPAR‐responsive luciferase reporter, followed by treatment with WY14643 (30 μM) for 24 hours as indicated. Luciferase activity was measured in these cells. All data are presented as the mean ± SD. For data shown in panel A: *comparison between control and WY14643 groups; ∧comparison between control and shPAQR3 groups; #shPAQR3 and shPAQR3+WY14643 groups; one symbol for P < 0.05, two symbols for P < 0.01, three symbols for P < 0.001. For data shown in panels B‐F: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To investigate cellular oxygen consumption rates, an index of mitochondrial oxidation function, we used a Seahorse Bioscience extracellular flux analyzer to analyze HepG2 cells that were stably transfected with control lentivirus or a lentivirus‐containing PAQR3‐specific shRNAs. As shown in Figure 3D, the bioenergetics profiles and the calculated oxygen consumption rates indicated that Paqr3 knockdown significantly increased the basal and maximal mitochondrial respiratory capacity, which is consistent with the observed increase in the genes involved in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation upon PAQR3 down‐regulation.

We then investigated the effects of PAQR3 on PPARα transactivation activity using a PPAR‐responsive luciferase reporter assay.42 HepG2 cells were stably infected with an empty vector or a PAQR3‐overexpressing lentivirus, followed by treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide or the PPARα agonist WY14643. As expected, WY14643 treatment resulted in the stimulation of the luciferase activity (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, both the basal and WY14643‐induced luciferase activity was significantly inhibited by PAQR3 overexpression (Fig. 3E). In contrast, Paqr3 knockdown could elevate both the basal and WY14643‐induced luciferase activity (Fig. 3F). In HEK293T cells, PAQR3 overexpression inhibited the activity of the PPAR‐responsive luciferase reporter, whereas Paqr3 knockdown stimulated it (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo). These results collectively demonstrate that PAQR3 can regulate the transactivation activity of PPARα in hepatocytes.

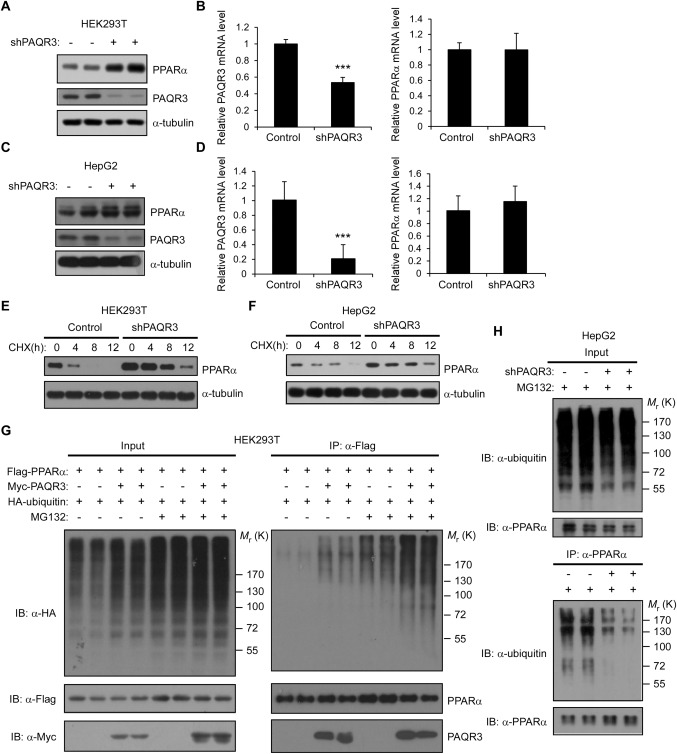

PAQR3 REGULATES PPARΑ PROTEIN STABILITY

We next explored the potential mechanisms underlying PAQR3 regulation of PPARα activity. We examined whether PAQR3 could modulate PPARα messenger RNA (mRNA) and/or protein levels. In HEK293T cells, Paqr3 knockdown drastically elevated PPARα steady state protein levels (Fig. 4A). However, Paqr3 knockdown had no effect on PPARα mRNA levels (Fig. 4B). The same situation occurred in HepG2 cells, where Paqr3 knockdown increased PPARα protein levels but not mRNA levels (Fig. 4C,D). Paqr3 knockdown also increased steady state PPARα protein levels in primary hepatocytes (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo). Because PAQR3 could alter PPARα at the protein level, we next analyzed whether PAQR3 impacted the half‐life of the PPARα protein. Paqr3 knockdown in both HEK293T and HepG2 cells could markedly reduce the degradation rate of newly synthesized PPARα protein in the presence of cycloheximide (Fig. 4E,F and http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo). Thus, these data indicated that PAQR3 could modulate PPARα protein stability.

Figure 4.

PAQR3 regulates PPARα stability and polyubiquitination. (A‐D) Paqr3 knockdown increases PPARα protein levels without changing its mRNA levels. Lentivirus‐containing control shRNAs or PAQR3‐specific shRNAs were used to infect HEK293T or HepG2 cells, followed by immunoblotting and RT‐PCR to determine PPARα protein and mRNA levels, respectively. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with PPARα expression plasmids (A, B). Endogenous PPARα was detected in HepG2 cells (C, D). Data are presented as the mean ± SD, ***P < 0.001. (E, F) Paqr3 knockdown elevates PPARα protein stability. The cells used in panels A and C were treated with 100 μg/mL of cycloheximide (CHX) for different lengths of time and then harvested for immunoblotting with the antibodies as indicated. (G) PAQR3 promotes PPARα ubiquitination. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with HA‐tagged ubiquitin, Myc‐tagged PAQR3, and Flag‐tagged PPARα as indicated. At 24 hours after the transfection, the cells were pretreated with or without MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours, followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting (IB) with antibodies as indicated. (H) Paqr3 knockdown decreases endogenous PPARα polyubiquitination. HepG2 cells were stably transfected with lentivirus‐expressing control shRNAs or PAQR3‐specific shRNAs. The cells were pretreated with MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours, and then the cell lysates were used in IP and IB with the antibodies as indicated.

To determine whether PAQR3 could affect the proteasome‐mediated degradation of PPARα protein, we analyzed PPARα protein polyubiquitination levels in the presence or absence of MG132, a proteasome inhibitor. In the presence of MG132, PPARα polyubiquitination levels were enhanced by PAQR3 overexpression in HEK293T cells (Fig. 4G), indicating that PAQR3 could increase PPARα ubiquitination and promote its degradation. In agreement with this conclusion, Paqr3 knockdown in HEK293T cells reduced PPARα polyubiquitination, whereas overexpression of a shRNA‐resistant PAQR3 abrogated this reduction (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo). Consistently, Paqr3 knockdown in HepG2 cells also reduced the polyubiquitination of endogenous PPARα (Fig. 4H). Collectively, these data support the conclusion that PAQR3 has a positive effect on PPARα ubiquitination and degradation.

In the cell, ubiquitinated proteins can be degraded by both proteasome‐ and lysosome‐mediated pathways. To elucidate the pathway, we treated HEK293T cells with MG132 to block the proteasome pathway or chloroquine to block lysosome function. Interestingly, MG132, but not chloroquine, could markedly enhance PPARα protein accumulation with or without Paqr3 knockdown (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo). We also investigated whether ubiquitinated PPARα is linked to lysine 48 or 63 of ubiquitin. Using ubiquitin mutants, we found that PPARα is mainly linked to lysine 48 in the ubiquitin chain (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo). Taken together, these data indicate that PAQR3 promotes PPARα ubiquitination and degradation mainly through the proteasome pathway.

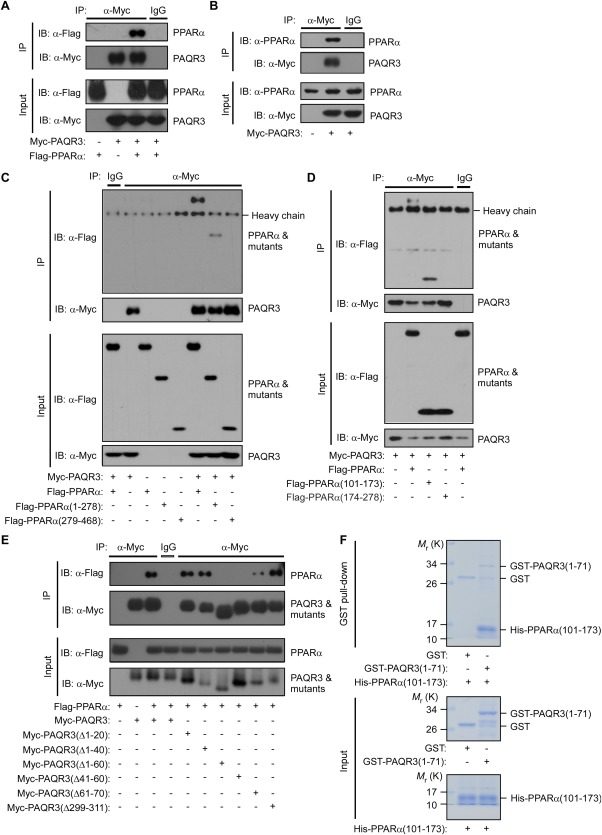

INTERACTION BETWEEN PPARΑ AND PAQR3

Because PAQR3 could modulate the function of PPARα by controlling its degradation, we postulated that PAQR3 might physically interact with PPARα. Consistent with our hypothesis, a co‐immunoprecipitation experiment in HEK293T cells revealed that overexpressed PAQR3 could associate with overexpressed PPARα (Fig. 5A). Moreover, endogenous PPARα could be co‐immunoprecipitated by an anti‐Myc antibody when Myc‐tagged PAQR3 was expressed (Fig. 5B). We next explored the functional domains in PPARα involved in this interaction. Similar to other typical nuclear receptors, PPARα has modular structures consisting of five domains, including an N‐terminal transactivation domain (AF1), a highly conserved DNA‐binding domain and a C‐terminal ligand‐binding domain enclosing a ligand‐dependent transactivation function (AF2).43 The DNA‐binding domain confers PPARα the ability to bind to PPAR response elements in the promoters of target genes as an obligate heterodimer with retinoid X receptor. Co‐immunoprecipitation assay revealed that PAQR3 could interact with PPARα amino acid (aa) residues 1‐278, which contain the N‐terminal AF1 domain and the DNA‐binding domain (Fig. 5C). Further analysis revealed that PAQR3 interacted with aa 101‐173, which contain the PPARα DNA‐binding domain, but not with aa 174‐278, which contain the PPARα hinge domain (Fig. 5D). We also identified the domains in PAQR3 involved in the interaction with PPARα using a series of PAQR3 deletion mutants. As shown in Figure 5E, the Δ1‐60aa and Δ41‐60aa PAQR3 deletion mutants could not interact with PPARα, whereas the association between PAQR3 and PPARα was retained by the Δ1‐40aa and Δ61‐70aa deletion mutants, indicating that PAQR3 N‐terminal aa 41‐60 are required for PPARα interaction. Furthermore, we investigated whether there was a direct interaction between PAQR3 and PPARα. PAQR3 N‐terminal aa 1‐71 were fused with glutathione‐S‐transferase (GST) and PPARα aa 101‐173 were linked to a His‐containing vector. The PAQR3 aa 1‐71 fusion protein, but not the GST control, could pull down in vitro–synthesized His‐tagged PPARα protein (Fig. 5F), suggesting that the PAQR3 NH2 terminus interacts directly with the PPARα DNA‐binding domain.

Figure 5.

PAQR3 interacts with PPARα. (A) Cell lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐tagged PPARα and/or Myc‐tagged PAQR3 were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting (IB) with the antibodies as indicated. (B) Interaction of PAQR3 with endogenous PPARα in Hepa1‐6 cells. Hepa1‐6 cells were transiently transfected with Myc‐tagged PAQR3 and the cell lysates were used for IP and IB with the antibodies as indicated. (C‐E) Identification of the structural domains in PPARα and PAQR3 involved in the interaction. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the plasmids as indicated, followed by IP and IB with the antibodies as indicated. (F) Direct interaction between PAQR3 and PPARα GST pull‐down assay was used to analyze the in vitro binding of purified His‐tagged PPARα (101‐173 aa) with purified GST‐fused PAQR3 (1‐71 aa).

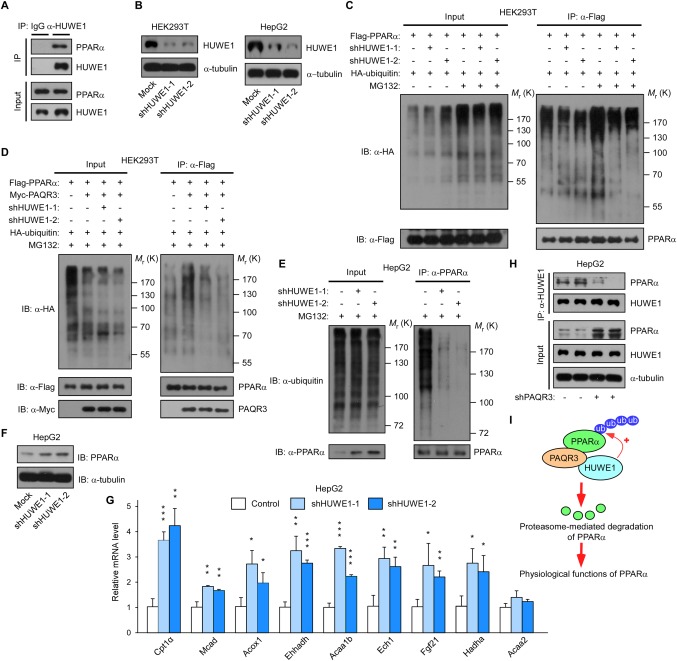

PAQR3 PROMOTES PPARα UBIQUITINATION THROUGH E3 UBIQUITIN LIGASE HUWE1

We next tried to identify the potential E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in PPARα polyubiquitination by mass spectrometry. Myc‐tagged PAQR3 and Flag‐tagged PPARα were coexpressed in HEK293T cells. The PPARα protein was purified from cells using an anti‐Flag antibody with protein A/G beads, and the associated proteins were identified by way of mass spectrometry. Among the E3 ubiquitin ligases identified by mass spectrometry, the HECT‐domain E3 ligase HUWE1 had the highest abundance (data not shown). Thus, we focused on HUWE1 in our subsequent studies. We first confirmed the interaction between endogenous PPARα and endogenous HUWE1 in HepG2 cells using a co‐immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 6A). We then attempted to knockdown Huwe1 expression with two independent shRNAs. These two shRNAs could markedly reduce Huwe1 expression in both HEK293T and HepG2 cells (Fig. 6B). Next, we investigated whether HUWE1 functioned as an E3 ubiquitin ligase for PPARα. In the presence of MG132, PPARα polyubiquitination was drastically reduced by both HUWE1 shRNAs in HEK293T cells (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, the elevated polyubiquitination of PPARα by PAQR3 overexpression was blunted by both HUWE1 shRNAs (Fig. 6D), indicating that PAQR3‐induced ubiquitination of PPARα is mediated by HUWE1. We also found that the polyubiquitination of endogenous PPARα was significantly blocked by Huwe1 knockdown in HepG2 cells upon MG132 treatment (Fig. 6E). Consistently, PPARα steady state protein levels were elevated by Huwe1 knockdown (Fig. 6F), suggesting that HUWE1‐mediated polyubiquitination could modulate PPARα protein stability. Functionally, a number of PPARα target genes involved in fatty acid oxidation were significantly increased by Huwe1 knockdown in HepG2 cells (Fig. 6G). Because these results suggest that PAQR3‐induced ubiquitination of PPARα is mediated by HUWE1, we postulated that PAQR3 may act as an adapter protein to aid in the interaction between HUWE1 and PPARα. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that the interaction between endogenous HUWE1 and endogenous PPARα was reduced by Paqr3 knockdown in HepG2 cells (Fig. 6H). Taken together, these results indicate that PAQR3 promotes PPARα ubiquitination and degradation by recruiting HUWE1, thereby affecting PPARα functions (Fig. 6I).

Figure 6.

PAQR3 promotes PPARα polyubiquitination through the E3 ubiquitin ligase HUWE1. (A) Interaction of endogenous PPARα with endogenous HUWE1. Cell lysates from HepG2 cells were used in immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting (IB) with the antibodies as indicated. (B) Analysis of Huwe1 knockdown efficiency. Both HEK293T and HepG2 cells were infected with lentivirus‐expressing control shRNAs or HUWE1‐specific shRNAs. The cell lysates were used in IB. (C) Huwe1 knockdown reduces PPARα ubiquitination. HEK293T cells that stably expressed lentiviruses with control shRNAs or HUWE1‐specific shRNAs were transiently transfected with plasmids as indicated. At 24 hours after transfection, the cells were treated with or without MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours, followed by IP and IB with the antibodies as indicated. (D) Huwe1 knockdown abrogates PAQR3‐stimuated polyubiquitination of PPARα. HEK293T cells in C were transfected with the plasmids as indicated. At 24 hours after transfection, the cells were pretreated with MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours before IP and IB using the antibodies as indicated. (E) Huwe1 knockdown decreases endogenous PPARα polyubiquitination. HepG2 cells were stably transfected with lentivirus‐expressing control shRNAs or HUWE1‐specific shRNAs. The cells were pretreated with MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours, followed by IP and IB. (F) Huwe1 knockdown elevates PPARα basal protein levels. The HepG2 cells in panel E were used for IB with the antibodies as indicated. (G) Huwe1 knockdown increases the expression of PPARα target genes. The cells in panel E were used for quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR to determine the expression of PPARα target genes. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 compared with the control group. (H) Paqr3 knockdown decreases the interaction between PPARα and HUWE1. HepG2 cells were stably transfected lentivirus‐expressing control shRNAs or PAQR3‐specific shRNAs. The cell lysate was used for IP and IB to detect endogenous PPARα and endogenous HUWE1. (I) Model depicting the coordinated action of PAQR3 and HUWE1 in PPARα polyubiquitination and degradation. PAQR3 functions as an adaptor protein to facilitate the interaction between the ubiquitin ligase HUWE1 and PPARα and promotes PPARα ubiquitination/degradation.

Discussion

It is well established that PPARα plays a central role in the starvation response by directly stimulating the transcription of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and ketone body production.9, 44 In the present study, we identified that PAQR3 modulates PPARα function both in vitro and in vivo. Paqr3 deficiency or deletion in the liver promotes fasting‐induced fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis, contributing to the improvement of hepatic steatosis upon long‐term nutrient deprivation. PAQR3 negatively regulates PPARα by promoting PPARα polyubiquitination and degradation through the E3 ubiquitin ligase HUWE1. We propose that PAQR3 functions as an important player to coordinate lipid metabolism in the body by regulating both lipid anabolism and catabolism in the liver. PAQR3 positively regulates lipid anabolism by facilitating the function of SREBPs39 and negatively regulates lipid catabolism by inhibiting the function of PPARα. Therefore, the net effect of a PAQR3 deficiency is a reduction in lipid accumulation in both fed (mainly by modulating SREBPs) and fasted (mainly by modulating PPARα) states. As a result, both high‐fat diet–induced hepatic steatosis and fasting‐induced hepatic steatosis are ameliorated by a PAQR3 deficiency in mice.

In the present study, we revealed the molecular mechanism underlying PPARα polyubiquitination‐mediated degradation. Our study supports an earlier observation showing that PPARα turnover can be regulated by the ubiquitin‐proteasome system in a ligand‐dependent manner.45 Mechanistically, we demonstrated that PAQR3 promotes PPARα polyubiquitination and degradation through the E3 ubiquitin ligase HUWE1. Thus, our study broadens the spectrum of biological activities regulated by HUWE1 and highlights its involvement in lipid metabolism by regulating PPARα. Interestingly, the specific deletion of HUWE1 in pancreatic β cells leads to reduced β cell mass with aging, resulting in severe diabetes before reaching 1 year of age,46, 47 indicating that HUWE1 is involved in metabolic regulation. This notion is also supported by our finding that Huwe1 knockdown up‐regulated the expression of PPARα target genes at the cellular level (Fig. 6G). Interestingly, HUWE1 expression was up‐regulated by fasting in mice, and this increase was abrogated by PAQR3 deletion (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo).

It is noteworthy that the mRNA levels of endocrine hormone fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) were elevated under fasting conditions when PAQR3 was deficient in the liver (Figs. 1 and 2). Consistently, serum FGF21 levels were also elevated by Paqr3 knockdown/deletion in the liver upon fasting (Figs. 1H and 2H). FGF21, a member of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) superfamily, has recently emerged as a major regulator of metabolism and energy utilization. FGF21 enhances energy expenditure and improves glucose homeostasis via changes in adiponectin and ceramide.48 Because FGF21 expression can be modulated by PAQR3, it is possible that part of the metabolism‐modulating effects of PAQR3 are due to its regulation of FGF21. Thus, the functional link between PAQR3 and FGF21 in the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism deserves further investigation.

In conclusion, we have shown that PAQR3 plays an important role in regulating lipid catabolism in response to nutrient deprivation by modulating PPARα function. Because PAQR3 can regulate both lipid catabolism and anabolism in a coordinated way, targeting PAQR3 would be a promising strategy to control blood lipid levels and improve metabolism disorders in the clinical setting. Our previous study indicated that blocking PAQR3 function can lower cholesterol synthesis in the mouse liver.39 It will be interesting to investigate whether blocking PAQR3 function also lowers lipid levels by improving fatty acid oxidation. Another important issue that must be addressed is the coordination of the lipid‐modulating functions of PAQR3 with its tumor suppressor activity. Studies at cellular, animal, and human levels have indicated that PAQR3 has a strong tumor suppressor activity in various types of cancers; however, it is unknown whether the regulation of lipid metabolism by PAQR3 contributes to its tumor suppressor activity. Addressing this important issue will undoubtedly shed light on the functional involvement of lipid metabolism in cancer development, thus providing a new strategy to control cancer.

Author names in bold designate shared co‐first authorship.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo.

Supporting Information 1

Potential conflicts of interest: Nothing to report.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31630036 and 81390350 to Y.C.), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant 2016YFA0500103 to Y.C.), and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grants XDA12010102, QYZDJ‐SSW‐SMC008, and ZDRW‐ZS‐2016‐8 to Y.C.).

REFERENCES

- 1. Browning JD, Horton JD. Molecular mediators of hepatic steatosis and liver injury. J Clin Invest 2004;114:147‐152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu XQ, Elder BD, Bilz S, Befroy D, et al. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem 2004;279:32345‐32353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanyal AJ. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;2:46‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spiegelman BM, Heinrich R. Biological control through regulated transcriptional coactivators. Cell 2004;119:157‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Desvergne B, Michalik L, Wahli W. Transcriptional regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev 2006;86:465‐514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feige JN, Auwerx J. Transcriptional coregulators in the control of energy homeostasis. Trends Cell Biol 2007;17:292‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chawla A, Repa JJ, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X‐files. Science 2001;294:1866‐1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gross B, Pawlak M, Lefebvre P, Staels B. PPARs in obesity‐induced T2DM, dyslipidaemia and NAFLD. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2017;13:36‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kersten S, Seydoux J, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Desvergne B, Wrahli W. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha mediates the adaptive response to fasting. J Clin Invest 1999;103:1489‐1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leone TC, Weinheimer CJ, Kelly DP. A critical role for the peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha (PPAR alpha) in the cellular fasting response: The PPAR alpha‐null mouse as a model of fatty acid oxidation disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:7473‐7478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guerre‐Millo M, Gervois P, Raspe E, Madsen L, Poulain P, Derudas B, et al. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha activators improve insulin sensitivity and reduce adiposity. J Biol Chem 2000;275:16638‐16642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chou CJ, Haluzik M, Gregory C, Dietz KR, Vinson C, Gavrilova O, et al. WY14,643, a peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha (PPAR alpha) agonist, improves hepatic and muscle steatosis and reverses insulin resistance in lipoatrophic A‐ZIP/F‐1 mice. J Biol Chem 2002;277:24484‐24489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim H, Haluzik M, Asghar Z, Yau D, Joseph JW, Fernandez AM, et al. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐alpha agonist treatment in a transgenic model of type 2 diabetes reverses the lipotoxic state and improves glucose homeostasis. Diabetes 2003;52:1770‐1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wadosky KM, Willis MS. The story so far: post‐translational regulation of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors by ubiquitination and SUMOylation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012;302:H515‐H526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim JH, Park KW, Lee EW, Jang WS, Seo J, Shin S, et al. Suppression of PPAR gamma through MKRN1‐mediated ubiquitination and degradation prevents adipocyte differentiation. Cell Death Different 2014;21:594‐603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Watanabe M, Takahashi H, Saeki Y, Ozaki T, Itoh S, Suzuki M, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM23 regulates adipocyte differentiation via stabilization of the adipogenic activator PPAR gamma. Elife 2015;4:e05615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li JJ, Wang RS, Lama R, Wang XJ, Floyd ZE, Park EA, et al. Ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 regulates PPAR gamma stability and adipocyte differentiation in 3T3‐L1 cells. Sci Rep 2016;6:38550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hou YZ, Moreau F, Chadee K. PPARγ is an E3 ligase that induces the degradation of NFκB/p65. Nat Commun 2012;3:1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodriguez JE, Liao JY, He J, Schisler JC, Newgard CB, Drujan D, et al. The ubiquitin ligase MuRF1 regulates PPARalpha activity in the heart by enhancing nuclear export via monoubiquitination. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2015;413:36‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gopinathan L, Hannon DB, Peters JM, Vanden Heuvel JP. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐alpha by MDM2. Toxicol Sci 2009;108:48‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huibregtse JM, Scheffner M, Beaudenon S, Howley PM. A family of proteins structurally and functionally related to the E6‐AP ubiquitin‐protein ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:2563‐2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen D, Kon N, Li M, Zhang W, Qin J, Gu W. ARF‐BP1/Mule is a critical mediator of the ARF tumor suppressor. Cell 2005;121:1071‐1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhao X, Heng JI, Guardavaccaro D, Jiang R, Pagano M, Guillemot F, et al. The HECT‐domain ubiquitin ligase Huwe1 controls neural differentiation and proliferation by destabilizing the N‐Myc oncoprotein. Nat Cell Biol 2008;10:643‐653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhong Q, Gao W, Du F, Wang X. Mule/ARF‐BP1, a BH3‐only E3 ubiquitin ligase, catalyzes the polyubiquitination of Mcl‐1 and regulates apoptosis. Cell 2005;121:1085‐1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bernassola F, Karin M, Ciechanover A, Melino G. The HECT family of E3 ubiquitin ligases: multiple players in cancer development. Cancer Cell 2008;14:10‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adhikary S, Marinoni F, Hock A, Hulleman E, Popov N, Beier R, et al. The ubiquitin ligase HectH9 regulates transcriptional activation by myc and is essential for tumor cell proliferation. Cell 2005;123:409‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Senyilmaz D, Virtue S, Xu XJ, Tan CY, Griffin JL, Miller AK, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology and function by stearoylation of TFR1. Nature 2015;525:124‐128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sung MK, Porras‐Yakushi TR, Reitsma JM, Huber FM, Sweredoski MJ, Hoelz A, et al. A conserved quality‐control pathway that mediates degradation of unassembled ribosomal proteins. Elife 2016;5:e19105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dominguez‐Brauer C, Hao Z, Elia AJ, Fortin JM, Nechanitzky R, Brauer PM, et al. Mule regulates the intestinal stem cell niche via the Wnt pathway and targets EphB3 for proteasomal and lysosomal degradation. Cell Stem Cell 2016;19:205‐216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Feng L, Xie XD, Ding QR, Luo XL, He J, Fan FJ, et al. Spatial regulation of Raf kinase signaling by RKTG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:14348‐14353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luo X, Feng L, Jiang X, Xiao F, Wang Z, Feng GS, et al. Characterization of the topology and functional domains of RKTG. Biochem J 2008;414:399‐406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xie XD, Zhang YX, Jiang YH, Liu WZ, Ma H, Wang ZZ, et al. Suppressive function of RKTG on chemical carcinogen‐induced skin carcinogenesis in mouse. Carcinogenesis 2008;29:1632‐1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang Y, Jiang X, Qin X, Ye D, Yi Z, Liu M, et al. RKTG inhibits angiogenesis by suppressing MAPK‐mediated autocrine VEGF signaling and is downregulated in clear‐cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2010;29:5404‐5415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jiang YH, Xie XD, Li ZG, Wang Z, Zhang YX, Ling ZQ, et al. Functional cooperation of RKTG with p53 in tumorigenesis and epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res 2011;71:2959‐2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang X, Li X, Fan F, Jiao S, Wang L, Zhu L, et al. PAQR3 plays a suppressive role in the tumorigenesis of colorectal cancers. Carcinogenesis 2012;33:2228‐2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang X, Wang L, Zhu L, Pan Y, Xiao F, Liu W, et al. PAQR3 modulates insulin signaling by shunting phosphoinositide 3‐kinase p110alpha to the Golgi apparatus. Diabetes 2013;62:444‐456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang L, Wang X, Li Z, Xia T, Zhu L, Liu B, et al. PAQR3 has modulatory roles in obesity, energy metabolism, and leptin signaling. Endocrinology 2013;154:4525‐4535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu DQ, Wang Z, Wang CY, Zhang DY, Wan HD, Zhao ZL, et al. PAQR3 controls autophagy by integrating AMPK signaling to enhance ATG14L‐associated PI3K activity. EMBO J 2016;35:496‐514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu D, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Jiang W, Pan Y, Song BL, et al. PAQR3 modulates cholesterol homeostasis by anchoring Scap/SREBP complex to the Golgi apparatus. Nat Commun 2015;6:8100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Badman MK, Pissios P, Kennedy AR, Koukos G, Flier JS, Maratos‐Flier E. Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by PPAR alpha and is a key mediator of hepatic lipid metabolism in ketotic states. Cell Metab 2007;5:426‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Montagner A, Polizzi A, Fouche E, Ducheix S, Lippi Y, Lasserre F, et al. Liver PPARalpha is crucial for whole‐body fatty acid homeostasis and is protective against NAFLD. Gut 2016;65:1202‐1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 15‐Deoxy‐delta 12, 14‐prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR gamma. Cell 1995;83:803‐812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Poulsen L, Siersbaek M, Mandrup S. PPARs: fatty acid sensors controlling metabolism. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2012;23:631‐639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lefebvre P, Chinetti G, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Sorting out the roles of PPAR alpha in energy metabolism and vascular horneostasis. J Clin Invest 2006;116:571‐580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Blanquart C, Barbier O, Fruchart JC, Staels B, Glineur C. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha (PPARα) turnover by the ubiquitin‐proteasome system controls the ligand‐induced expression level of its target genes. J Biol Chem 2002;277:37254‐37259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kon N, Zhong J, Qiang L, Accili D, Gu W. Inactivation of arf‐bp1 induces p53 activation and diabetic phenotypes in mice. J Biol Chem 2012;287:5102‐5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang L, Luk CT, Schroer SA, Smith AM, Li X, Cai EP, et al. Dichotomous role of pancreatic HUWE1/MULE/ARF‐BP1 in modulating beta cell apoptosis in mice under physiological and genotoxic conditions. Diabetologia 2014;57:1889‐1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Holland WL, Adams AC, Brozinick JT, Bui HH, Miyauchi Y, Kusminski CM, et al. An FGF21‐adiponectin‐ceramide axis controls energy expenditure and insulin action in mice. Cell Metab 2013;17:790‐797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29786/suppinfo.

Supporting Information 1