Abstract

This study was conducted to test our hypothesis that intramuscular fat (IMF) accumulation increases in pigs fed on a low lysine diet during the dark period than those fed on the same diet during the light period. Using barrows aged 6 weeks, we monitored whether serum glucose and insulin levels were affected by light conditions. Two diets with different levels of lysine, 0.78% (LL diet) and 1.37% (control diet) were prepared. Eight pigs were fed on the diet during the light period, while the remaining pigs were fed during the dark period. The pigs were fed either the LL diet or the control diet. Although IMF contents of Longissimus dorsi (LD) muscle were higher in the pigs fed on a LL diet (p < .05), the light conditions had no effect. Low dietary lysine caused reduction in serum glucose levels (p < .05) and serum insulin levels (p = .0613). However, they were also unaffected by the lighting conditions. To gain further insights, we determined the messenger RNA levels of insulin receptor, insulin receptor substrate 1, acetyl CoA carboxylase, and fatty acid synthase in LD and Rhomboideus muscles and in the liver.

Keywords: dietary lysine, intramuscular fat, lighting condition, pig

1. INTRODUCTION

We previously reported that dietary low lysine promotes accumulation of intramuscular fat (IMF) in porcine muscle (Katsumata, Kobayashi, Matsumoto, Tsuneishi, & Kaji, 2005; Katsumata, Kyoya, Ishida, Ohtsuka, & Nakashima, 2012; Kobayashi, Ishida, Ashihara, Nakashima, & Katsumata, 2012). We subjected the pigs to ad libitum feeding in these experiments to allow them to obtain sufficient energy for IMF accumulation. When the pigs were allowed ad libitum feeding, 70%–90% of their eating behavior was observed during the light period (Dourmad, 1993; Wangsness, Gobble, & Sherritt, 1982). As we did not observe any change in the feeding behavior of pigs in our previous studies, we surmised that pigs in our previous studies also consumed the diets mainly during the light period. The effects of timing of food intake on body composition of animals have been studied in laboratory rodents. As rodents are nocturnal, they rest during the light period; that is the light period is their resting period. According to Bray et al. (2013), restricting access to diet during the light period (the resting period) in mice led to higher diet intake compared to mice with restricted access to diet during the dark period. In addition, energy expenditure and oxidation of fatty acids are reduced in mice with restricted access to diet during the light period (Bray et al., 2013). These results suggest that diet consumption only during the resting period causes higher adiposity in animals. Wu et al. (2011) suggested that when animals are allowed energy intake until immediately before the resting period, more fat is accumulated in their bodies. Although the effects of timing of food intake on body composition of pigs have not yet been elucidated, it may be reasonable to assume that restricting energy intake only during the resting period (dark period) or allowing energy intake until immediately before the resting period causes higher adiposity in pigs as well. If this is also the case for IMF accumulation, we may be able to improve the efficiency of IMF accumulation by controlling the timing of food intake. Thus, we hypothesized that IMF accumulation increases in pigs when fed on a low lysine diet during their resting period (the dark period) compared to those fed on a low lysine diet during their active period (the light period). To test this hypothesis, we compared the IMF content of pigs that received a low lysine diet during the dark period to those pigs that received a low lysine diet during the light period. Due to the limitations in room size and cage size, we used 6‐week‐old pigs in this experiment.

The response of the pigs to low dietary lysine and high IMF accumulation is very reproducible. However, the exact modes of action of such accumulation are still unknown. One of the candidates involved may be the downstream signaling of insulin; we observed lower circulating levels of insulin in pigs that received a low lysine diet while the circulating levels of glucose were not affected (Kobayashi et al., 2012). These results indicate that sensitivities of peripheral tissues to insulin are higher in pigs subjected low dietary lysine. Thus, in addition to testing the above hypothesis, we also verified whether low dietary lysine reduced circulating levels of insulin in pigs fed on a low lysine diet during the dark period.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Ethical considerations

All the experimental procedures in this study were performed in accordance with the animal experiment regulations of National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO), and were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of NARO Institute of Livestock and Grassland Science (NILGS). The certification number of this experiment issued by the committee is 12032653.

2.2. Animals, diets, and outline of the experiment

Sixteen barrows (Landrace × Large White) × Duroc cross‐breeds, from four litters, that is four barrows from each litter, aged 6 weeks were used. Pigs were moved to the chambers 7 days prior to the start of the experiment. The average initial body weight was 14.8 ± 0.2 kg. In this experiment, we used two different air‐conditioned chambers (chambers A and B) located in the pig unit of NILGS. The lighting cycle of the chambers were 12 hr light : 12 hr dark. Chamber A was bright from 07.00 to 19.00 hours while chamber B was bright from 19.00 to 7.00 hours. Fluorescent light was fitted to both chmbers A and B. The luminous intensities at the center of the chambers measured using an apparatus (Testo540; Testo K.K., Yokohama, Japan) were 466 lx and 557 lx for chambers A and B, respectively. Since there are no windows in the chambers, the inside of the chambers was completely dark when the light was switched off. However, around 16.30 hours each day, the light in the chamber B was turned on for less than 15 min to clean the cages and the chambers. Two pigs from a litter were kept in chamber A, while the others were kept in chamber B. The pigs were kept individually in metabolism cages (1.6 × 1.3 m). We prepared two diets with different levels of lysine (0.78% and 1.37%, Table 1). Hereafter, the diets are referred as LL diet and control diet, respectively. The two diets were iso‐energetic and iso‐nitrogenous, and contained equal amounts of nutritionally essential amino acids apart from lysine. Further, the diets contained all nutritionally essential amino acids apart from lysine in the amounts recommended by the Japanese Feeding Standard for Swine (National Agriculture and Bio‐oriented Research Organization 2005). The amount of the diet given to the pigs each day was equivalent to 4% of their body weight. The daily amount of the diet was equally divided into three parts and each portion was given to the pigs at 09.00, 13.00, and 16.00 hours, respectively. All the pigs consumed the diets completely at 19.00 hours each day. Thus, the pigs kept in chamber A consumed the diets during the light cycle, while the pigs kept in chamber B consumed the diets during the dark cycle. When we fed the pigs in chamber B during the dark period (i.e., at 13.00 and 16.00 hours), we used a torch light to ensure the correct position of the feeders. One pig in a chamber was assigned to the control diet, while the other pig kept in the same chamber was assigned to the LL diet. The pigs were fed these diets throughout the 3‐week experimental period. Hence, the design of this experiment was a two‐way factorial; lighting condition and dietary lysine level were considered as independent variables.

Table 1.

Composition of the control and the low lysine diets on an as‐fed basis

| Control | Low lysine | |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredients (%) | ||

| Corn | 68.00 | 68.00 |

| Soya bean meal | 6.50 | 6.50 |

| Fish meal | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| Corn gluten feed | 11.05 | 11.05 |

| Soya bean oil | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| HCl‐lysine | 0.75 | — |

| dl‐methionine | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| l‐threonine | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| l‐tryptophan | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| l‐valine | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| l‐isoleucine | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| l‐glutamic acid | — | 0.375 |

| Glycine | — | 0.375 |

| Tricalcium phosphate | 1.60 | 1.60 |

| Sodium chloride | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Vitamin and mineral mixa | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Antibioticsb | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Calculated chemical composition | ||

| Crude protein (%) | 16.4 | 16.3 |

| Digestible energy (Mcal/kg) | 3.40 | 3.39 |

| Lysine (%) | 1.37 | 0.78 |

aProviding per kg of diet: vitamin A, 11,000 IU; vitamin D3, 1,170 IU; vitamin E, 30 mg; thiamine nitrate, 4.3 mg; riboflavin, 5.9; pyridoxine hydrochloride, 8.9; calcium phantothetic acid, 11.0; nicotinamide, 45.6; choline chloride, 1264; Mn (manganese carbonate) 16.5; Zn (zinc sulfate) 46.8; Cu (copper sulfate) 8.0; Fe (iron sulfate) 123; I (calcium iodate) 0.80.

bProviding mg/kg of diet: tyrocin 100; tetracycline 100.

2.3. Sample collection and analysis

At the end of experiment, the pigs were fed their last meal at 09.00 hours and the pigs were killed at 13.00 hours in an abattoir at NILGS by electrical stunning, followed by exsanguination. Thus, the sample was collected approximately 4–5 hr after the last meal. Serum samples were obtained and stored at −40°C until analysis of insulin and glucose. Immediately after killing, samples of Longissimus dorsi (LD), Rhomboideus muscles, and liver were taken for determination of messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of insulin receptor (IR), insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1), acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC), and fatty acid synthase (FAS). Tissue samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis. A large portion of each sample of LD muscle was used to determine the IMF content; these samples were kept at 4°C overnight and then minced. The IMF content was measured as crude fat by following the ether extraction method.

The levels of serum insulin (ELISA kit; Shibayagi, Gunma, Japan) and glucose (Glucose Test Wako; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) were determined using commercially available kits.

Total RNA was extracted from the frozen muscle sample using a commercial reagent (RNA Lipid Tissue Kits; Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan) following the manufacturer's instruction. First‐strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using random hexamer primers (Takara, Osaka, Japan) and a reverse transcriptase (ReverTra Ace; Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Quantification of mRNA was performed with a LightCycler ST300 (Roche Diagnostics K.K., Tokyo, Japan) and using a commercial kit (QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit; Qiagen K.K., Tokyo, Japan). The porcine 18S ribosomal RNA (18S) was used as an internal standard. The primers were designed based on the sequence of porcine IR, FAS, ACC, and 18S (XM_005654749, NM_001244489, NM_001099930.1, AF175308.1, and AY265350, respectively). The sequences of forward and reverse primers for each amplicon are as follows: IR, 5′‐CAGCGATGTATTTCCATGTTCTGT‐3′ and 5′‐GCGTTTCCCTCGTACACCAT‐3′; IRS1, 5′‐TCTCCTCGACACCCAGTGC‐3′ and 5′‐CTTGAGGGCGCTGTTTGAA‐3′; ACC 5′‐CTCCAGGACAGCACAGATCA‐3′ and 5′‐GCCGAAACATCTCTGGGATA‐3′; FAS, 5′‐CTCCTTGGAACCGTCTGTGT‐3′ and 5′‐AACGTCCTGCTGAAGCCTAA‐3′; 18S 5′‐AGTCGGCATCGTTTATGGTC‐3′ and 5′‐CGCGGTTCTATTTTGTTGGT‐3′. The PCR conditions were as follows: pre‐denaturing temperature 95°C for 15 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturing at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 60°C for 20 s, and extending at 72°C for 15 s. In order to assess whether the PCR products were single and had specific amplicons, we checked the melt curves of the amplicons produced by each primer set and confirmed that all the curves had single peaks.

Statistical significance of the effects of lighting conditions and dietary lysine levels were assessed by analysis of variance for a randomized‐block design, where litter was the block, and lighting conditions and dietary lysine levels were the main effects, by using the GLM procedure of SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). When the main effects were significant, the significance of differences between least square means were assessed by the least significant difference method using the LSMEANS statement of the GLM procedure of SAS. Results are presented as least square means ± pooled standard errors.

3. RESULTS

Growth performance and IMF content of LD muscle are shown in Table 2. Neither dietary lysine levels nor lighting conditions affected feed intake in the pigs. Although daily body weight gain and feed efficiencies were lower in the pigs that received LL diet (p < .05), lighting conditions did not have any effect. IMF content of LD muscle was higher in the pigs that received the LL diet (p < .05), and lighting conditions did not affect the IMF content.

Table 2.

Growth performances and intramuscular fat content (n = 4)

| Light | Dark | Pooled SE | LysineA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | LL | Control | LL | |||

| Feed intake (kg/3 week) | 15.2 | 14.8 | 14.7 | 14.3 | 0.6 | |

| Body weight gain (kg/3 week) | 8.7a | 6.9b | 8.9a | 6.3b | 0.3 | ** |

| Feed efficiency | 0.58a | 0.46b | 0.61a | 0.44b | 0.02 | ** |

| Intramuscular fat (%) | 0.68b | 1.15a | 0.61b | 0.96ab | 0.12 | ** |

AThe effects of dietary lysine concentrations **p < .01.

The means with different superscripts differ (a, b; p < .05).

Table 3 shows serum glucose and insulin levels. Serum glucose level was lower in the pigs that received the LL diet (p < .05) but lighting conditions had no effect. Low dietary lysine tended to also reduce the serum insulin level (p = .0613), and lighting conditions once again did not have any effect. We also calculated the ratio of the concentration of glucose to insulin as an indicator of sensitivities of peripheral tissues to insulin in terms of glucose uptake. These results are shown in Table 3. We observed a tendency of an interaction between dietary lysine levels and lighting conditions (p = .052); dietary lysine levels did not affect the ratio in the pigs that received the diets during the light period, while dietary low lysine increased the ratio in the pigs that received the diets during the dark period.

Table 3.

Serum glucose, insulin, and glucose/insulin ratio (n = 4)

| Light | Dark | Pooled SE | LA | LysB | IntC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | LL | Control | LL | |||||

| Glucose (mg/100 ml) | 134.5ab | 127.5b | 143.3a | 130.5ab | 8.9 | * | ||

| Insulin (ng/ml) | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.13 | p = .061 | ||

| Glucose/insulin | 355 | 249 | 342 | 699 | 104 | p = .065 | p = .052 | |

A,B,CThe effects of lighting conditions, dietary lysine concentrations and their interactions, respectively. *p < .05.

The means with different superscripts differ (a, b; p < .05).

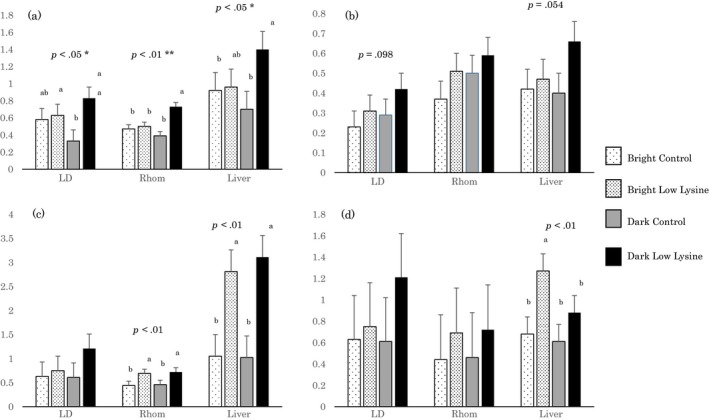

Abundance of mRNA of insulin receptor, IRS1, ACC, and FAS in LD and Rhomboideus muscles and liver are shown in Figure 1. Interactions between dietary lysine levels and lighting conditions were observed for levels of insulin receptor mRNA in all the tissues examined (p < .05); although dietary lysine levels did not affect the mRNA levels in pigs that received each diet during the light period, they were higher in the pigs that received the LL diet during the dark period than those in pigs that received the control diet during the dark period. Neither dietary lysine levels nor lighting conditions affected the levels of IRS1 mRNA. The quantity of ACC mRNA in Rhomboideus muscles and liver were higher in the pigs that received the LL diet (p < .05). Levels of FAS mRNA were affected by the treatments only in the liver; they tended to be higher during the light period (p < .10), while low dietary lysine contributed to an increase in FAS mRNA levels (p < .01).

Figure 1.

Abundance of messenger RNA (mRNA) of insulin receptor (a), insulin receptor substrate 1 (b), acetyl CoA carboxylase (c), and fatty acid synthase (d) in Longissimus dorsi and Rhomboideus muscles and liver. Bars are expressed as least square means and error bars are their pooled standard errors, n = 4. The abundances are expressed as relative ratios of the target mRNAs to the internal standard mRNA (18S ribosomal RNA). LD; longissimus dorsi muscle, Rhom; rhomboideus muscle. p values are the results of analysis of variance on the effects of dietary lysine levels. * and **, the interactions between lighting conditions and dietary lysine levels are significant, p < .05 and p < .01, respectively. a and b, differences between least square means (p < .05)

4. DISCUSSION

In terms of increase in IMF accumulation by low dietary lysine, the results of this study are consistent with previous observations. However, our hypothesis that IMF accumulation increases in pigs fed on a low lysine diet during their resting period (the dark period) was rejected. Indeed, although the average levels of ACC and FAS mRNA in LD muscle were higher in the pigs that received a low lysine diet, the lighting conditions did not affect them. For the pigs consuming the entire diet provided each time, the amount of the diet each day was equivalent to 4% of their body weight. Hence, the pigs were subjected to a mild restricted feeding condition. In other studies, when mice were fed only during the light period (i.e., their resting period), they consumed higher total energy per day compared with mice fed only during the dark period (i.e., the active period) (Bray et al., 2013). If the pigs had been allowed free access to the diets during either the light or the dark period in the present study, diet intake would naturally have been higher in the pigs receiving the diet during the dark period, and hence the accumulation of IMF would have been affected by the lighting conditions. Further studies are required to elucidate this aspect.

Dietary low lysine tended to reduce the levels of serum insulin. This result is consistent with our previous observation (Kobayashi et al., 2012). As other studies have also shown that low dietary lysine reduced circulating levels of insulin in pigs (Ren, Zhao, Li, & Meng, 2007; Roy, Lapierre, & Bernier, 2000), reduction of insulin levels due to low dietary lysine seems to be a reliable phenomenon. When 4‐month‐old pigs were fed a meal equivalent to approximately 1.5× their maintenance energy, the levels of insulin peaked within an hour after the feeding and returned to the pre‐feeding levels 6 hr post‐feeding (Metzler‐Zebeli et al., 2015). In the present study, we evaluated basal levels of insulin rather than postprandial elevated levels of insulin because approximately 70% of maintenance of energy was provided at 09.00 hours, and blood was drawn 4–5 hr post‐feeding. As the amount of energy (i.e., the amount present in a meal) was less than 50% of that used in the study by Metzler‐Zebeli et al. (2015), 4–5 hr may be sufficient for insulin to return to near basal levels. Although we did not measure the levels of plasma lysine in the present study, the concentrations of plasma lysine of the pigs that received a low lysine diet were approximately a quarter of those of the pigs that received a control diet (97 vs. 393 nmol/ml, Katsumata, Matsumoto, Kobayashi, & Kaji (2008)). Thus, low lysine concentrations may be associated with low basal insulin levels. Effects of low dietary lysine on postprandial rise in insulin (i.e., insulin secretion) in pigs need to be examined.

An interesting finding of the present study is the effect of lighting conditions on the glucose‐insulin system. Although the lighting conditions did not affect insulin levels, the average concentration of the pigs that received the LL diet during the dark period were found to be the lowest. The average ratio of levels of glucose to insulin in the pigs that received the LL diet during the dark period were found to be the highest. In addition, there were interactions of the dietary lysine levels and the lighting conditions on the level of insulin receptor mRNA, both in the muscles and liver. Such effects of the dietary lysine were detected only during the dark period and the levels in the pigs that received the LL diet during the dark period were the highest. These results suggest that lighting conditions may affect insulin secretion, glucose uptake, and insulin signaling in pigs. These effects may be dependent on the dietary lysine levels. The effects of lighting conditions on endocrine hormones, and on melatonin are well‐known. Circulating levels of melatonin are higher at night compared to levels during the day, which is also applicable for pigs (Andersson, 2001). Oral administration of melatonin to rats for 9 weeks reduced insulin levels (Peschke, 2010; Ríos‐Lugo et al., 2010). Glucose uptake and phosphorylation of IRS1 and phosphoinositide 3‐kinase of the C2C12 muscle cells were up‐regulated by treatments with melatonin (Ha et al., 2006). Hence, melatonin reduces circulating levels of insulin, but promotes glucose uptake by stimulating insulin signaling. The lowest levels of insulin and the highest ratio of glucose to insulin were recorded in the pigs that received the LL diet during the dark period, and could be linked to melatonin. However, in pigs, neither lower circulating levels of insulin during the night (during the dark period) nor reduction of circulating levels of insulin due to exogenous melatonin have been reported to date. Regarding the effects of amino acids, tryptophan has been shown to enhance circulating levels of melatonin in rats, chicken, and goats (Huether, Poeggeler, Reimer, & George, 1992; Ma, Zhang, Song, Sun, & Jia, 2012). However, the effects of lysine have not been reported to date. Finally, it is important to consider the timing of sample collection and its impact. In the present study, we obtained the samples under natural light conditions; the samples were obtained 15–30 min after the pigs placed in chamber B (i.e., in the dark condition) were exposed to the natural light. Even though melatonin could affect circulating levels of insulin in pigs, whether or not the effects of melatonin would last for 15–30 min after exposure to bright light is unclear and should be examined. Indeed, how dietary lysine and lighting conditions affect insulin secretion, glucose uptake, and insulin signaling is an attractive research topic that warrants further investigation.

Our hypothesis that IMF accumulation increases in pigs fed on a low lysine diet during their resting period (the dark period), was rejected in the present study. However, we may need to re‐test the hypothesis under a condition of free access to diet because dietary intake would be higher in the pigs that received diet during the dark period if only they were allowed free access to additional amounts of diet. In this experiment, the light in chamber B was turned on once around 16.30 hours each day to clean the cages and the chamber. Hence, the internal clock of the pigs of the dark group could have been disturbed, and such disturbances can influence the study results. However, we believe that the glucose‐insulin system of the pig is affected by lighting conditions and this effect is dependent on dietary lysine levels. The effects of lighting conditions and dietary lysine on insulin secretion, glucose uptake, and insulin signaling were discussed in this study. Further studies are required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of these effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the Program for the Promotion of Basic and Applied Research for Innovation in Bio‐oriented Industry. We thank the members of the Pig Unit of NILGS for their care of the pigs and their support with sample collection. Statistical analysis was performed using the supercomputer facility of the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Research IT (AFFRIT), Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF), Japan.

Katsumata M, Kobayashi H, Ashihara A, Ishida A. Effects of dietary lysine levels and lighting conditions on intramuscular fat accumulation in growing pigs. Anim Sci J. 2018;89:988–993. 10.1111/asj.13019

REFERENCES

- Andersson, H. (2001). Plasma melatonin levels in relation to the light‐dark cycle and parental background in domestic pigs. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 42, 287–294. 10.1186/1751-0147-42-287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, M. S. , Ratcliffe, W. F. , Grenett, M. H. , Brewer, R. A. , Gamble, K. L. , & Young, M. E. (2013). Quantitative analysis of light‐phase restricted feeding reveals metabolic dyssynchrony in mice. International Journal of Obesity, 37, 843–852. 10.1038/ijo.2012.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourmad, J. Y. (1993). Standing and feeding behavior of the lactating sow: Effect of feeding level during pregnancy. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 37, 311–319. 10.1016/0168-1591(93)90120-e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ha, E. , Yim, S. V. , Chung, J. H. , Yoon, K. S. , Kang, I. , Cho, Y. H. , & Baik, H. H. (2006). Melatonin stimulates glucose transport via insulin receptor substrate‐1/phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase pathway in C2C12 murine skeletal muscle cells. Journal of Pineal Research, 41, 67–72. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2006.00334.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huether, G. , Poeggeler, B. , Reimer, A. , & George, A. (1992). Effect of tryptophan administration on circulating melatonin levels in chicks and rats evidence for stimulation of melatonin synthesis and release in the gastrointestinal tract. Life Sciences, 51, 945–953. 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90402-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata, M. , Kobayashi, S. , Matsumoto, M. , Tsuneishi, E. , & Kaji, Y. (2005). Reduced intake of dietary lysine promotes accumulation of intramuscular fat in the longissimus dorsi muscles of finishing gilts. Animal Science Journal, 76, 237–244. 10.1111/j.1740-0929.2005.00261.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata, M. , Kyoya, T. , Ishida, A. , Ohtsuka, M. , & Nakashima, K. (2012). Dose‐dependent response of intramuscular fat accumulation in longissimus dorsi muscle of finishing pigs to dietary lysine levels. Livestock Science, 149, 41–45. 10.1016/j.livsci.2012.06.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata, M. , Matsumoto, M. , Kobayashi, S. , & Kaji, Y. (2008). Reduced dietary lysine enhances proportion of oxidative fibers in porcine skeletal muscle. Animal Science Journal, 79, 347–353. 10.1111/j.1740-0929.2008.00536.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, H. , Ishida, A. , Ashihara, A. , Nakashima, K. , & Katsumata, M. (2012). Effects of dietary low level of threonine and lysine on the accumulation of intramuscular fat in porcine muscle. Bioscience Biotechnology Biochemistry, 76, 2347–2350. 10.1271/bbb.120589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. , Zhang, W. , Song, W. H. , Sun, P. , & Jia, Z. H. (2012). Effects of tryptophan supplementation on cashmere fiber characteristics, serum tryptophan, and related hormone concentrations in cashmere goats. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 43, 239–250. 10.1016/j.domaniend.2012.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler‐Zebeli, B. U. , Eberspächer, E. , Grüll, D. , Kowalczyk, L. , Molnar, T. , & Zebeli, Q. (2015). Enzymatically modified starch ameliorates postprandial serum triglycerides and lipid metabolome in growing pigs. PLoS ONE, 10, e0130553 10.1371/journal.pone.0130553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Agriculture and Bio‐oriented Research Organization . (2005). Japanese Feeding Standard for Swine (2005). Tokyo: Japan Livestock Industry Association. [Google Scholar]

- Peschke, E. (2010). Long‐term enteral administration of melatonin reduces plasma insulin and increases expression of pineal insulin receptors in both Wistar and type 2‐diabetic Goto‐Kakizaki rats. Journal of Pineal Research, 49, 373–381. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2010.00804.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J. B. , Zhao, G. Y. , Li, Y. X. , & Meng, Q. X. (2007). Influence of dietary lysine level on whole‐body protein turnover, plasma IGF‐I, GH and insulin concentration in growing pigs. Livestock Science, 110, 126–132. 10.1016/j.livsci.2006.10.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos‐Lugo, M. J. , Cano, P. , Jiménez‐Ortega, V. , Fernández‐Mateos, M. P. , Scacchi, P. A. , Cardinali, D. P. , & Esquifino, A. I. (2010). Melatonin effect on plasma adiponectin, leptin, insulin, glucose, triglycerides and cholesterol in normal and high fat‐fed rats. Journal of Pineal Research, 49, 342–348. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2010.00798.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, N. , Lapierre, H. , & Bernier, J. F. (2000). Whole‐body protein metabolism and plasma profile of amino acids and hormones in growing barrows fed diets adequate or deficient in lysine. Canadian Journal of Animal Science, 80, 585–595. 10.4141/a98-057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wangsness, P. J. , Gobble, J. L. , & Sherritt, G. W. (1982). Feeding behavior of lean and obese pigs. Physiology & Behavior, 24, 407–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T. , Sun, L. , ZhuGe, F. , Guo, X. , Zhao, Z. , Tang, R. , … Fu, Z. (2011). Differential roles of breakfast and supper in rats of a daily three‐meals schedule upon circadian regulation and physiology. Chronobiology International, 28, 890–903. 10.3109/07420528.2011.622599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]