Abstract

Background

ASSURE‐CSU revealed differences in physician and patient reporting of angioedema. This post hoc analysis was conducted to evaluate the actual rate of angioedema in the study population and explore differences between patients with and without angioedema.

Methods

This international observational study assessed 673 patients with inadequately controlled chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). Physicians abstracted angioedema data from medical records, which were compared with patient‐reported data. Patients in the Yes‐angioedema category had angioedema reported in the medical record and a patient‐reported source. For those in the No‐angioedema category, angioedema was reported in neither the medical record nor a patient‐reported source. Those in the Misaligned category had angioedema reported in only one source. Statistical comparisons between Yes‐angioedema and No‐angioedema categories were conducted for measures of CSU activity, health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), productivity and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU). Regression analyses explored the relationship between Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score and angioedema, adjusting for important covariates.

Results

Among evaluable patients, 259 (40.3%), 173 (26.9%) and 211 (32.8%) were in the Yes‐angioedema, No‐angioedema and Misaligned category, respectively. CSU activity and impact on HRQoL, productivity, and HCRU was greater for Yes‐angioedema patients than No‐angioedema patients. After covariate adjustment, mean DLQI score was significantly higher (indicating worse HRQoL) for patients with angioedema versus no angioedema (9.88 vs 7.27, P < .001). The Misaligned category had similar results with Yes‐angioedema on all outcomes.

Conclusions

Angioedema in CSU seems to be under‐reported but has significant negative impacts on HRQoL, daily activities, HCRU and work compared with no angioedema.

Keywords: angioedema, economic burden, observational study, quality of life, urticaria

Highlights.

Nearly one‐third of CSU patients in ASSURE‐CSU reported having experienced angioedema in the past 12 months but did not have physician‐reported angioedema as documented in their medical records.

Patients with angioedema had greater CSU activity, HRQoL and productivity impairment, and resource utilization than those without. After controlling for other factors, angioedema significantly affected DLQI total score.

Among patients with inadequately controlled symptomatic CSU, the proportion with angioedema may be higher than previously thought.

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is characterized by the presence of hives, angioedema or both, recurring for 6 weeks or longer, in the absence of identifiable triggers.1, 2 Angioedema is defined as rapid swelling at a deeper level under the skin than hives, occurring on the face, inside the mouth or elsewhere on the body.2, 3 It is estimated that 33%‐67% of patients with CSU exhibit both hives and angioedema, 29%‐65% exhibit only hives and 1%‐13% exhibit only angioedema.4, 5

Patients who experience CSU as concurrent hives and angioedema often experience a longer duration of disease than patients who experience only hives.6, 7 Angioedema may be disfiguring or painful, may limit daily activities and may have a significant impact on quality of life.8, 9 Patients with CSU‐associated angioedema often experience concern over their health status, at times worrying that swelling episodes may cause problems with breathing or may be life‐threatening.9 A real‐world multicentre study in Germany has shown that in a 6‐month period, more than 40% of patients with inadequately controlled CSU experienced angioedema; among these patients, 78% rated their angioedema as severe or moderate in intensity, and a mean of 34 days with angioedema was reported during the 6‐month period.5 In addition to its considerable symptom burden, recurrent angioedema (in those with hereditary angioedema) can lead to absenteeism and can have a negative impact on work productivity.10

The observational, multinational ASSURE‐CSU (ASsessment of the Economic and Humanistic Burden of Chronic Spontaneous/Idiopathic URticaria PatiEnts) study aimed to characterize the patient population with inadequately controlled CSU and to evaluate the burden of disease.11, 12 Analyses of ASSURE‐CSU data revealed different rates of CSU‐associated angioedema between physician and patient reports.12 The objectives of this post hoc analysis were to provide a better estimate of angioedema rates among CSU patients in the ASSURE‐CSU study by aligning patient and physician reports and to analyse differences in patient characteristics as well as humanistic and economic burden between individuals with and without angioedema.

2. METHODS

2.1. ASSURE‐CSU study design

ASSURE‐CSU was an observational, noninterventional, multinational, multicentre study conducted at urticaria specialty centres in Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Methodology11 and overall results12 have been reported previously. In summary, recruitment of 700 patients was planned. Adult patients who had a clinician‐confirmed CSU diagnosis, had received at least one treatment course with an H1‐antihistamine, had been symptomatic for more than 12 months and were currently symptomatic despite treatment were eligible12; patients with urticaria that was predominantly of the inducible form were ineligible. Study data were collected via a retrospective 12‐month patient medical record abstraction (MRA) by physicians, a cross‐sectional patient survey and a prospective 8‐day patient diary. The appropriate national‐, local‐ and site‐level ethical approvals were obtained, and all patients provided written informed consent. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.13

2.2. Study measures

Study measures relevant to this analysis included the occurrence of angioedema as reported in the physician MRA, the cross‐sectional patient survey and the patient diary. Specifically, physicians reported from the medical chart whether the patient had angioedema associated with his or her CSU ever, at the time of diagnosis, and/or within the past 12 months. In the patient survey, completed at enrolment, patients answered whether they had experienced angioedema ever, during the past 12 months, within the past 4 weeks and/or currently (at survey completion); patients also answered questions about the duration and location of angioedema, as well as the symptoms they experienced with angioedema (swelling, itching and pain) and what they would do to seek treatment (or not) during an angioedema episode. In the Urticaria Patient Daily Diary (UPDD), completed for each of 7 days following enrolment, patients indicated whether they had experienced “rapid swelling, also called angioedema,” during the past 24 hours.

Additional measures explored in this analysis included demographic data, comorbidities and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) related to CSU during the previous 12 months, as abstracted by physicians in the MRA. Additional measures collected in the patient survey included validated patient‐reported outcome measures such as the Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU‐Q2oL)14, 15 and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)16 and HCRU. The 7‐day UPDD17 also included the twice‐daily Urticaria Activity Score over 7 Days (UAS7TD),18 daily sleep interference and activity impairment, in addition to the aforementioned occurrence and management of angioedema. On the 8th day, patients completed the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI), which has a recall period of 7 days.19

2.3. Statistical analysis

Frequency of angioedema within the past 12 months and misalignment of angioedema reporting between physician and patient data sources were evaluated. For patients in the Yes‐angioedema category, physician and patient data sources agreed that the patient had experienced angioedema. For these cases, the MRA and either the patient survey or patient diary indicated that the patient had experienced angioedema in the past 12 months. For patients in the No‐angioedema category, physician and patient data sources agreed that the patient had not experienced angioedema. For these cases, all 3 data sources indicated no angioedema in the past 12 months. For the Misaligned category, the physician and patient data sources (either patient survey or diary) did not agree as to whether the patient had experienced angioedema. For these cases, the physician data source indicated no angioedema during the past 12 months while one of the patient sources indicated that angioedema had occurred, or the physician source indicated that the patient had experienced angioedema in the past 12 months while the patient sources did not. If the angioedema classification was missing either from the MRA or from both patient data sources (survey and diary), the patient was assigned to a Missing category and excluded from analysis.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population by angioedema classification (Yes‐angioedema, No‐angioedema, Misaligned). Disease activity was determined by UAS7TD score bands: UAS7TD = 0‐6 (urticaria‐free or well‐controlled urticaria activity), 7‐15 (mild activity), 16‐27 (moderate activity) and 28‐42 (severe activity).20 Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) measures were analysed by published methodology where available.

Statistical comparisons of patients with and without angioedema were conducted using t tests or Kruskal‐Wallis tests for continuous variables and chi‐square tests for categorical variables. Tests were performed between those in the Yes‐angioedema and No‐angioedema categories; patients who fell into the Misaligned category were not included in the statistical comparisons.

Regression modelling was used to explore whether the relationship between DLQI score and angioedema remained significant after adjusting for important covariates. An analysis of covariance model was used to evaluate the effect of angioedema on DLQI total score. Adjustment covariates included UAS7TD score, age, sex, country, disease duration from diagnosis to enrolment and selected comorbidities at enrolment (hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, Hashimoto's disease and asthma). UAS7TD score, age and disease duration were treated as continuous variables. Least‐squares mean estimates and standard errors were estimated for each angioedema classification; patients in the Misaligned category were combined with patients in the Yes‐angioedema category for the primary analysis. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted in which the Misaligned category was excluded from the comparison.

All tests were performed at a nominal significance level of α = .05 with 2‐sided, single degree‐of‐freedom tests. No correction was made for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using SAS for Windows statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Initial angioedema frequency over the past 12 months

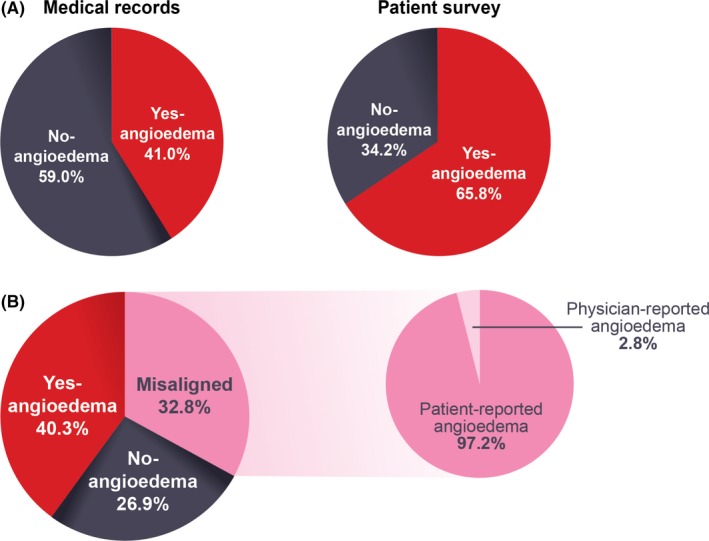

According to the MRA, physicians reported that 276 of 673 patients enrolled (41.0%) had experienced CSU‐associated angioedema within the past 12 months, with a mean (standard deviation [SD]) of 19.0 (42.13) angioedema episodes during this period. Among the 649 patients who completed the survey, 427 (65.8%) patients reported having had angioedema within the past 12 months (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Frequency of angioedema in the past 12 months. (A) Initial frequency: Angioedema in the past 12 months was more frequently reported by patients who completed the survey (65.8%, 427/649 patients) than recorded in the medical record (41.0%, 276/673 patients). (B) Revised frequency: Of the 32.8% of patients (211/643) with misaligned reporting of angioedema in the past 12 months, 97.2% (205/211) reported having had angioedema when it was not noted in the medical record

Among the 614 patients who completed the diary over 1 week, 294 (47.9%) patients reported that they had angioedema at least 1 day; the mean (SD) patient‐reported number of days with angioedema was 3.2 (1.92) over the 7 days. The occurrence of angioedema and number of days with angioedema increased with increasing disease activity over that week.12

3.2. Postalignment angioedema frequency over the past 12 months

Of the 673 patients enrolled, 643 patients had recorded data for assigning the angioedema classification, and 30 patients had missing data either in the MRA or from both patient data sources (survey and diary) and could not be classified. Of the 643 patients included in the angioedema analyses, 276 (42.9%) had angioedema according to the MRA, and 467 (72.6%) had angioedema according to one of the patient sources (survey or diary).

For the analyses, 259 patients (40.3%) were in the Yes‐angioedema category, 173 (26.9%) were in the No‐angioedema category, and 211 (32.8%) were in the Misaligned category. Of the 211 patients in the Misaligned category, 205 (97.2%) had angioedema recorded in one of the patient sources (survey or diary) but not in the MRA (Figure 1B; Table S1).

3.3. Patient demographics

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between patients in the Yes‐angioedema and No‐angioedema categories, except in duration of CSU and presence of Hashimoto's disease (Table 1). Patients in the Yes‐angioedema category had longer mean (SD) duration of disease from diagnosis to enrolment (61.7 [76.64] months) than those in the No‐angioedema category (46.1 [69.06]) (P < .05) and a higher prevalence of Hashimoto's disease (10.4% vs 2.9%; P < .01).

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics from the medical record abstraction, overall and by angioedema classification

| Patient characteristicsa | Total (n = 643) | Angioedema category | P valueb (yes vs no) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 259) | No (n = 173) | Misaligned (n = 211) | |||

| Age at enrolment (years) | .0906 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.0 (15.56) | 49.4 (14.45) | 46.8 (16.50) | 50.4 (15.95) | |

| Min, Max | 19.0, 89.0 | 20.0, 81.0 | 19.0, 89.0 | 19.0, 87.0 | |

| Female sex (%) | 469 (72.9) | 197 (76.1) | 117 (67.6) | 155 (73.5) | .0540 |

| Race and ethnicityc | 544 | 205 | 155 | 184 | .5262 |

| Caucasian/White (%) | 491 (90.3) | 189 (92.2) | 138 (89.0) | 164 (89.1) | |

| Other (%) | 44 (8.1) | 15 (7.3) | 14 (9.0) | 15 (8.2) | |

| Data not available (%) | 9 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.9) | 5 (2.7) | |

| Disease duration from diagnosis to enrolment (months) | .0486 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 57.3 (77.73) | 61.7 (76.64) | 46.1 (69.06) | 61.0 (85.43) | |

| Comorbid conditions at enrolment (%) | |||||

| Hypersensitivity to NSAIDs | 52 (8.1) | 28 (10.8) | 10 (5.8) | 14 (6.6) | .0833 |

| Hashimoto's disease | 43 (6.7) | 27 (10.4) | 5 (2.9) | 11 (5.2) | .0042 |

| Asthma | 71 (11.0) | 33 (12.7) | 18 (10.4) | 20 (9.5) | .5434 |

| CSU/CIU severity at the time of diagnosis (%) | 642 | 259 | 173 | 210 | .0101 |

| Mild | 71 (11.1) | 27 (10.4) | 32 (18.5) | 12 (5.7) | |

| Moderate | 202 (31.5) | 81 (31.3) | 53 (30.6) | 68 (32.4) | |

| Severe | 233 (36.3) | 98 (37.8) | 45 (26.0) | 90 (42.9) | |

| Data not available | 136 (21.2) | 53 (20.5) | 43 (24.9) | 40 (19.0) | |

| UAS7TD | |||||

| Mean (SD) UAS7TD | 17.3 (10.46) | 17.6 (10.55) | 14.6 (8.97) | 19.2 (11.05) | .0032 |

| UAS7TD band (%) | 600 | 244 | 161 | 195 | .0140 |

| 0‐6 | 98 (16.3) | 41 (16.8) | 28 (17.4) | 29 (14.9) | |

| 7‐15 | 204 (34.0) | 75 (30.7) | 73 (45.3) | 56 (28.7) | |

| 16‐27 | 182 (30.3) | 82 (33.6) | 40 (24.8) | 60 (30.8) | |

| 28‐42 | 116 (19.3) | 46 (18.9) | 20 (12.4) | 50 (25.6) | |

CIU, chronic idiopathic urticaria; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; MRA, medical record abstraction; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; SD, standard deviation; UAS7TD, Urticaria Activity Score over 7 Days, twice‐daily assessment.

For categorical variables, the total number of patients with nonmissing data is presented by angioedema category for each question along with “n (%)” for each possible response to the question. Except where otherwise noted, percentage denominators are the number of patients with nonmissing data for the applicable question.

P values shown from t tests for means of continuous variables and chi‐square tests for frequencies of categorical variables to compare patients who experience angioedema (Yes‐angioedema) with those who do not (No‐angioedema). Patients in the Misaligned category were not included in the statistical comparison. For race and ethnicity, due to the small number of patients in many of the race/ethnicity categories, all races other than white were combined for these comparisons. Patients whose race/ethnicity group is “data not available” were excluded from the statistical comparison.

Race and ethnicity data were not collected in France. For some categories of race and ethnicity, different terms were used across countries.

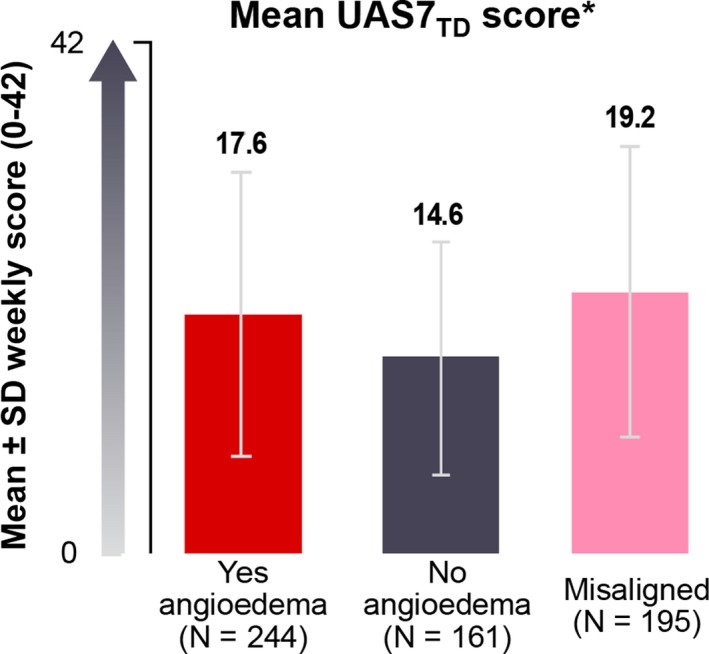

3.4. Urticaria severity and activity

More patients in the Yes‐angioedema category were reported to have severe CSU activity at diagnosis (37.8%) than those in the No‐angioedema category (26.0%) (Table 1). Mean (SD) UAS7TD score reported in the patient diary was higher for patients in the Yes‐angioedema category (17.6 [10.55]) than for those in the No‐angioedema category (14.6 [8.97]) (P < .01) (Figure 2). In line with this observation, more patients in the Yes‐angioedema category than in the No‐angioedema category had severe (UAS7TD 28‐42) disease activity (18.9% vs 12.4%) (Figure S1).19 Moreover, a significant difference was observed between patients in the Yes‐angioedema and No‐angioedema categories in the mean (SD) absolute number of hives over a week collected in the UPDD (147.9 [266.37] vs 77.1 [123.87], respectively).

Figure 2.

Mean urticaria activity score over 7 days, twice‐daily assessment (UAS7TD), by angioedema classification. UAS7TD scores were calculated by summing the average of twice‐daily assessments of hive count and itch score and summing these daily scores over 7 days. *P < .01 (Yes—angioedema vs No—angioedema). Patients who fell into the Misaligned group were not included in the statistical comparisons. SD, standard deviation. [Colour figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com/]

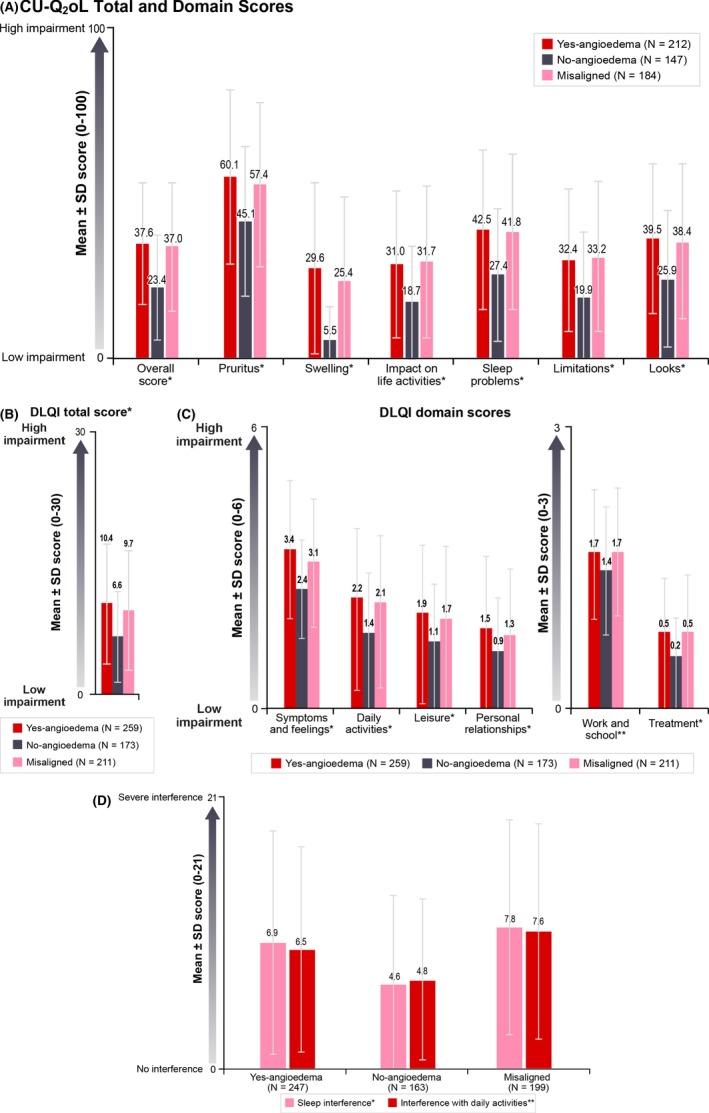

3.5. Effect of angioedema on HRQoL, sleep and daily activities

The mean (SD) CU‐Q2oL score for the overall patient sample was 33.6 (21.02). Mean (SD) CU‐Q2OL scores differed significantly between patients in the Yes‐angioedema and No‐angioedema categories (37.6 [20.81] vs 23.4 [17.12], P < .001), reflecting significantly lower HRQoL for patients with angioedema (Figure 3A). Significant differences were observed between patients with and without angioedema on all CU‐Q2oL domains.

Figure 3.

Impact of CSU on HRQoL, sleep and daily activities, overall and by angioedema classification. (A) CU‐Q2oL total and domain scores. Different CU‐Q2oL scale scores are used in Germany than in Canada, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and the UK. German CU‐Q2oL overall score and scale scores are presented in Figure S2; (B) DLQI total score; (C) DLQI domain scores; (D) Interference with sleep and interference with daily activities over a week, as reported on the Urticaria Patient Daily Diary, by angioedema classification. For all scores, a higher score means higher impairment. *P < .001 (Yes—angioedema vs No—angioedema); **P < .05 (Yes—angioedema vs No—angioedema). Patients who fell into the misaligned category were not included in the statistical comparisons. CU‐Q2oL, Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; HRQoL, health‐related quality of life; SD, standard deviation. [Colour figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com/]

On the DLQI, mean (SD) overall score for the entire sample was 9.1 (6.63) and for Yes‐angioedema and No‐angioedema groups were 10.4 (6.85) and 6.6 (5.21), respectively (P < .001) (Figure 3B). Again, significant differences were observed between patients with and without angioedema on all DLQI domains (Figure 3C). More patients in the Yes‐angioedema category (45.5%) than in the No‐angioedema category (20.4%) had DLQI scores >10 (indicating a very to extremely large effect on HRQoL21).

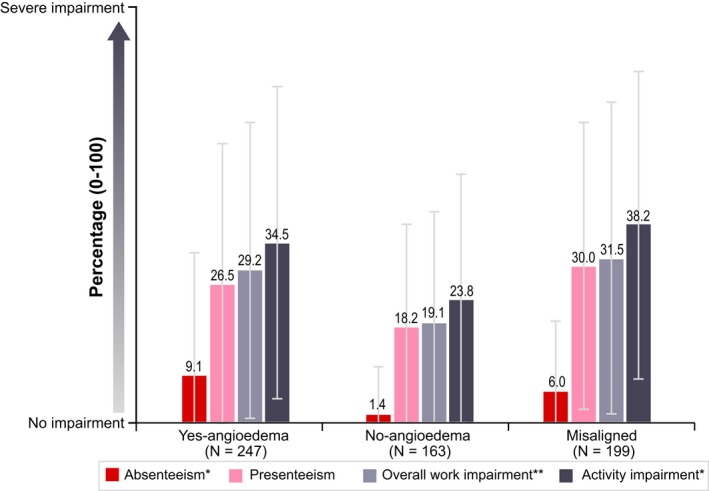

As patients reported on the UPDD, mean (SD) weekly scores for interference with sleep were higher for patients in the Yes‐angioedema category (6.9 [6.14]) than for patients in the No‐angioedema category (4.6 [4.92]) (P < .001), as were mean (SD) weekly scores for interference with daily activities (6.5 [5.68] vs 4.8 [4.39]; P < .05) (Figure 3D). Activity impairment measured by the mean percentage overall activity impairment score on the WPAI was also greater for patients in the Yes‐angioedema category than for patients in the No‐angioedema category (34.5% vs 23.8%; P < .001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI) results by angioedema classification. Absenteeism was defined as percentage of work time missed due to chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) in the past 7 days. Presenteeism was defined as percentage impairment while working due to CSU in the past 7 days. Overall work impairment was defined as percentage work impairment due to CSU in the past 7 days, incorporating both absenteeism and presenteeism using the following validated WPAI algorithm: overall work impairment = absenteeism + (1‐absenteeism)*presenteeism. *P < .001 (Yes—angioedema vs No—angioedema); **P < .05 (Yes—angioedema vs No—angioedema). Patients who fell into the misaligned category were not included in the statistical comparisons. SD, standard deviation; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment. [Colour figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com/]

3.6. Economic and societal impact of angioedema

Patients in the Yes‐angioedema category had greater HCRU, both documented in medical records and self‐reported, than patients in the No‐angioedema category (Table S2). According to the MRA, patients in the Yes‐angioedema category were more likely to have a CSU‐related emergency department visit than patients in the No‐angioedema category (24.7% vs 5.2%, P < .001) and were more likely to have one or more inpatient hospital stays in the past 12 months (11.6% vs 3.5%, P < .01). As reported in the patient diary, patients with angioedema were more likely to call a healthcare provider during the 7‐day window than patients without angioedema (7.3% vs 0.6%, P < .01).

Impact on work was greater among patients in the Yes‐angioedema category than among patients in the No‐angioedema category. Patients in the Yes‐angioedema category who completed the diary were more likely to have missed 1 or more hours of work in the 7‐day diary window than patients in the No‐angioedema category (27.6% vs 5.8%, P < .001), and mean (SD) number of days of work missed in the past 3 months was significantly higher for patients in the Yes‐angioedema versus the No‐angioedema category (4.7 [11.64]) vs 0.8 [3.86], P < .001). WPAI scores showed significantly greater absenteeism among patients in the Yes‐angioedema versus No‐angioedema categories (mean [SD] percentage absenteeism: 9.1% [23.22%] vs 1.4% [9.08%], P < .001), as well as significantly greater overall work impairment (mean [SD] percentage overall work impairment: 29.2% [28.48%) vs 19.1% [21.37%], P = .02) (Figure 4). Overall, angioedema was the second most common reason for missing work, after itching.

3.7. Characteristics of the misaligned angioedema category

Patients in the Misaligned category were compared descriptively with patients in the Yes‐angioedema and No‐angioedema categories and were found to be most similar to patients in the Yes‐angioedema category in all outcomes. Demographics were similar in terms of age, sex, disease duration from diagnosis to enrolment and CSU severity at diagnosis (Table 1). Similar proportions of patients in the Misaligned and Yes‐angioedema categories had moderate (UAS7TD 16‐27) or severe (UAS7TD 28‐42) disease activity (56.4% and 52.5%, respectively). When completing the survey, 52.2% of patients in the Misaligned category reported that their angioedema typically lasts more than 12 hours, compared with 47.8% of patients in the Yes‐angioedema category. The mean (SD) amount of swelling, on a scale of 0 to 10, was similar for patients in the Misaligned category (7.1 [2.12]) and those in the Yes‐angioedema category (7.2 [2.20]). In addition, the HRQoL impact of CSU was similar for patients in the Misaligned and Yes‐angioedema categories, as indicated by mean (SD) overall scores on the DLQI (10.4 [6.85] and 9.7 [6.87], respectively) and CU‐Q2oL (37.6 [20.81] and 37.0 [21.49], respectively) (Figure 3A,B). Percentage overall work impairment due to CSU was similar for patients in the Misaligned and Yes‐angioedema categories (mean [SD] = 31.5% [29.99%] and 29.2% (28.48%), respectively) (Figure 4).

3.8. DLQI regression analysis

Given the similarities in characteristics and outcomes among patients in the Misaligned and Yes‐angioedema categories, the Misaligned patients were combined with the Yes‐angioedema patients in the primary regression analysis of DLQI total score. After covariate adjustment, mean DLQI score was significantly higher for patients with angioedema versus without (9.88 vs 7.27, P < .001) (Table 2). Results were similar in the sensitivity analysis in which patients in the Misaligned angioedema category were excluded: mean DLQI total score was significantly higher for patients with angioedema versus without (9.69 vs 6.73, P < .001).

Table 2.

DLQI regression results

| Angioedema Classification | Within Group | Contrast in LS Mean | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | LS Mean | SE | Comparison | LS Mean | SE | 95% CI | P value | |

| Primary analysis: ANCOVA for DLQI total score by angioedema classification (assigning Misaligned category to Yes‐angioedema category) | ||||||||

| No‐angioedema | 150 | 7.27 | 0.850 | vs Yes | −2.61 | 0.558 | −3.71 to −1.51 | <.0001 |

| Yes‐angioedema | 399 | 9.88 | 0.722 | |||||

| Sensitivity analysis: ANCOVA for DLQI total score by angioedema classification (removing the Misaligned category) | ||||||||

| No‐angioedema | 150 | 6.73 | 0.902 | vs Yes | −2.96 | 0.586 | −4.12 to −1.81 | <.0001 |

| Yes‐angioedema | 232 | 9.69 | 0.795 | |||||

LS means, 95% CIs and P values are from an ANCOVA model with covariates: angioedema classification, UAS7TD score (continuous), age at enrolment (continuous), sex (male and female), country (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands and the UK), disease duration from diagnosis to enrolment (continuous) and comorbidities at enrolment (hypersensitivity to NSAIDs [yes/no], Hashimoto's [yes/no] and asthma [yes/no]). ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; CI, confidence interval; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; LS, least squares; n, number of subjects with data for all model inputs; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; SE, standard error; UAS7TD, Urticaria Activity Score over 7 days, twice‐daily assessment.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of this post hoc analysis revealed notable differences in reporting of angioedema between CSU patients and physicians in the ASSURE‐CSU study. The objective of this analysis was to align angioedema data in order to better estimate the actual rate of angioedema and to analyse differences between patients with and without angioedema. Angioedema was more frequently reported by patients than by physicians: 65.8% of patients who completed the survey reported having experienced angioedema during the past 12 months, whereas physicians reported that 41.0% of patients had experienced angioedema during the same time period. A large majority (97%) of patients with misaligned angioedema data did not have physician‐reported angioedema but reported having experienced angioedema in either the patient survey or diary. These findings suggest that the occurrence of angioedema may be under‐recognized among physicians (who may not routinely ask patients about angioedema symptoms), that patients may not always report their angioedema symptoms to physicians or that patients characterize some CSU‐related swelling as angioedema when a physician would classify it as hives or sometimes as swelling unrelated to urticaria.

ASSURE‐CSU patients with misaligned angioedema data appear most similar to patients with angioedema, in terms of disease duration; disease activity; and scores on patient‐reported outcome measures including the CU‐Q2oL, DLQI and WPAI. If patients in the Misaligned category were reclassified into the Yes‐angioedema category, which they closely resembled, the percentage of patients in the ASSURE‐CSU study with angioedema over 12 months would increase from 40.3% to 73.1%. Moreover, our analysis suggests that patients with more severe CSU are more likely to have angioedema. Physicians reported that more patients with angioedema than without had severe CSU at diagnosis, and patients with angioedema reported greater CSU activity as indicated by UAS7TD mean score than those without angioedema.

The primary ASSURE‐CSU analysis found that angioedema had a significant impact on HRQoL in patients with CSU, particularly with respect to emotional well‐being, fatigue and mood.12 The current analysis also revealed the considerable impact of angioedema on HRQoL, as indicated by CU‐Q2oL and DLQI scores, and its additional negative impact on top of itch and hives. Even after controlling for other factors, angioedema has a significant effect on the DLQI total score. In addition, patients with angioedema have additional impairment on work productivity and more HCRU than those without it, indicating that angioedema further contributes to the economic burden of inadequately controlled CSU.

Taken together, findings from these analyses suggest that physicians should ensure that patients understand the manifestations of angioedema and should routinely assess patients with CSU for presence of angioedema, which may enable more accurate estimates of the true prevalence and burden of angioedema. Appropriate tools available for evaluating angioedema activity and its impact on CSU patients’ lives should be used regularly in clinical practice.22, 23, 24 In patients with recurrent angioedema, CSU should be considered as one of the differential diagnoses.1, 25 Additionally, angioedema in CSU should prompt adequate treatment. The development of new treatments specifically for CSU has been shown to prevent angioedema and improve angioedema‐dependent and dermatology‐related quality of life.9, 26, 27, 28 Future research should explore the clinical course of angioedema in CSU—including the most commonly affected areas, the clinical differences compared with hereditary angioedema and evolution of symptoms over time—as well as the distinct management patterns that patients with angioedema in CSU require. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of angioedema in CSU29 and exploring differences in the general categories of angioedema (ie mast cell–induced and bradykinin‐induced) are also important areas for additional research.

Several limitations must be considered when the results of this study are interpreted. First, the study was conducted in specialized centres only, and physicians and centres were not selected systematically, owing to the small number of specialist units for this population. The resulting sample is not guaranteed to be representative of all medical settings and physicians treating patients with CSU. Second, the target population had had CSU for at least 12 months and had not responded adequately to treatment at the time of inclusion in the study; thus, the study does not reflect the entire population of patients with CSU but more patients with inadequately controlled CSU. Moreover, although patients received training about identifying angioedema and reporting it in the patient survey or diary, like all patient‐reported data, angioedema was still subject to patients’ individual interpretation of the symptom description and manifestation. In addition, data extracted by physicians from medical records were not independently validated.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Among this study population with inadequately controlled CSU, 40.3% had confirmed angioedema in the past 12 months, and 32.8% of patients had misaligned angioedema data (ie the majority reporting having experienced angioedema in the past 12 months without having it documented in their medical records). This suggests that a higher proportion of patients with inadequately controlled symptomatic CSU might have angioedema than previously thought. Patients with angioedema reported statistically significantly worse HRQoL and higher societal burden than patients without angioedema; patients in the Misaligned group reported similar impairment as patients with confirmed angioedema. Overall, the study found that angioedema has an incremental impact on societal and humanistic outcomes in CSU patients. These findings suggest the need for improved physician‐patient communication regarding angioedema for better symptom control in patients with inadequately controlled CSU.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

This research was performed under a research contract between RTI Health Solutions and Novartis Pharma AG and was funded by Novartis Pharma AG. K.H., S.H., D.McB., C.S. and D.W. are employees of RTI Health Solutions, which provides consulting and other research services to pharmaceutical, device, governmental and nongovernment organizations. In their salaried positions, they work with a variety of companies and organizations. They receive no payment or honoraria directly from these organizations for services rendered. M.M.B. is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG. H.T. is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.M.B., K.H. and D.McB. initiated the study. M.M.B., K.H., D.McB, C.S. and D.W. designed the study; M.A., F.B., W.C., H.O.E., A.G‐A., C.G., A.K., J‐P.L., C.L., A.M., M.M., A.N., J.O.d.F., G.S. and K.W. provided clinical input on the study design. K.H., D.McB., C.S. and D.W. managed data collection, and M.M.B., K.H., D.McB., S.H., C.S., H.T. and D.W. led the data analyses. M.M.B., M.A., F.B., W.C., H.O.E., A.G‐A., C.G., K.H., A.K., J‐P.L., C.L., A.M., M.M., D.McB., A.N., J.O.d.F., C.P., G.S., C.S., H.T., K.W. and D.W. interpreted the data. M.M.B., K.H., S.H., D.McB. and G.S. drafted the manuscript, and M.A., F.B., W.C., H.O.E., A.G‐A., C.G., A.K., J‐P.L., C.L., A.M., M.M., A.N., J.O.d.F., C.S., H.T., K.W. and D.W. revised it critically for intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for the work as a whole.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following recruiting physicians: Drs. Sameh Hanna, Jacques Hebert, Amin Kanani, Paul Keith, Gina Lacuesta, Jason Lee, G‐Daniel Schachter, Susan Waserman and Shahin Zanganeh in Canada; Drs. Emmanuelle Amsler‐Soria, Annick Barbaud, Claire Bernier, Laurence Bouillet, Jean‐Jacques Grob, Giordano Labadie, Laurent Machet, Paul Martin, Fabien Pelletier, Nadia Rasion‐Peyron, Delphine Staumont‐Salle and Manuelle Viguier in France; Drs. Andrea Bauer, Randolf Brehler, Hans Merk, Franziska Rueff, Petra Staubach‐Renz and Amir Yazdi in Germany; Drs. Ornella de Pità, Silvia Mariel Ferrucci, Maria Laura Flori, Giampiero Girolomoni, Giovanni Pellacani, Paolo Pigatto and Domenico Schiavino in Italy; Drs. Menno T. W. Gaastra, G. R. R. Kuiters, M. L. A. Schuttelaar, R. A. Tupker, Thomas Rustemeyer, Phyllis Spuls and Roy Gerth van Wijk in the Netherlands; Drs. Jesús Borbujo, Pablo de la Cueva, Alejandro Joral Badas, Moisés Labrador Hornillo, Ana Perez Montero, Javier Pedraz and Esther Serra in Spain; and Drs. Anthony Bewley, Seautak Cheung, Nyz Chiang, Venkata Gudi, Frances Humphreys, Dimtra Koumaki, John Reed and Donna Torley in the United Kingdom.

Kate Lothman of RTI Health Solutions provided medical writing services, which were funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

Sussman G, Abuzakouk M, Bérard F, et al. Angioedema in chronic spontaneous urticaria is underdiagnosed and has a substantial impact: Analyses from ASSURE‐CSU. Allergy. 2018;73:1724–1734. 10.1111/all.13430

REFERENCES

- 1. Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014;69:868‐887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rye Rasmussen EH, Bindslev‐Jensen C, Bygum A. Angioedema—assessment and treatment. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2012;132:2391‐2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Banerji A, Sheffer AL. The spectrum of chronic angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009;30:11‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev‐Jensen C, et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a GA²LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66:317‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maurer M, Staubach P, Raap U, et al. H1‐antihistamine‐refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: it's worse than we thought—first results of the multicenter real‐life AWARE study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017a;47:684‐692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Valk P, Moret G, Kiemeney L. The natural history of chronic urticaria and angioedema in patients visiting a tertiary referral centre. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:110‐113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sánchez‐Borges M, Caballero‐Fonseca F, Capriles‐Hulett A, González‐Aveledo L, Maurer M. Factors linked to disease severity and time to remission in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:964‐971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, et al. Development and construct validation of the angioedema quality of life questionnaire. Allergy. 2012;67:1289‐1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Staubach P, Metz M, Chapman‐Rothe N, et al. Effect of omalizumab on angioedema in H1‐antihistamine resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria patients: results from X‐ACT, a randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:1135‐1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lumry WR, Castaldo AJ, Vernon MK, Blaustein MB, Wilson DA, Horn PT. The humanistic burden of hereditary angioedema: impact on health‐related quality of life, productivity, and depression. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:407‐414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weller K, Maurer M, Grattan C, et al. ASSURE‐CSU: a real‐world study of burden of disease in patients with symptomatic chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015a;5:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maurer M, Abuzakouk M, Bérard F, et al. The burden of chronic spontaneous urticaria is substantial: real‐world evidence from ASSURE‐CSU. Allergy. 2017b;72:2005‐2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Medical Association . Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. October 2008. Available at: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/. Accessed April 16, 2016.

- 14. Baiardini I, Pasquali M, Braido F, et al. A new tool to evaluate the impact of chronic urticaria on quality of life: chronic urticaria quality of life questionnaire (CU‐Q2oL). Allergy. 2005;60:1073‐1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Młynek A, Magerl M, Hanna M, et al. The German version of the Chronic Urticaria Quality‐of‐Life Questionnaire: factor analysis, validation, and initial clinical findings. Allergy. 2009;64:927‐936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Flood EM, Zazzali JL, Devlen J. Demonstrating measurement equivalence of the electronic and paper formats of the urticaria patient daily diary in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Patient. 2013;6:225‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mathias SD, Dreskin SC, Kaplan A, Saini SS, Spector S, Rosén KE. Development of a daily diary for patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:142‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reilly M. Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire. 2004. http://www.reillyassociates.net/Index.html. Accessed December 14, 2013.

- 20. Stull D, McBride D, Tian H, et al. Analysis of disease activity categories in chronic spontaneous/idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1093‐1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: what do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:659‐664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weller K, Zuberbier T, Maurer M. Clinically relevant outcome measures for assessing disease activity, disease control and quality of life impairment in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria and recurrent angioedema. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015b;15:220‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weller K, Magerl M, Peveling‐Oberhag A, Martus P, Staubach P, Maurer M. The angioedema quality of life questionnaire (AE‐QoL) – assessment of sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2016;71:1203‐1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, et al. Development, validation, and initial results of the angioedema activity score. Allergy. 2013;68:1185‐1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maurer M, Magerl M, Metz M, Siebenhaar F, Weller K, Krause K. Practical algorithm for diagnosing patients with recurrent wheals or angioedema. Allergy. 2013;68:816‐819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maurer M, Sofen H, Ortiz B, Kianifard F, Gabriel S, Bernstein JA. Positive impact of omalizumab on angioedema and quality of life in patients with refractory chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria: analyses according to the presence or absence of angioedema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017c;31:1056‐1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zazzali JL, Kaplan A, Maurer M, et al. Angioedema in the omalizumab chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria pivotal studies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:370‐377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Finlay AY, Kaplan AP, Beck LA, et al. Omalizumab substantially improves dermatology‐related quality of life in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1715‐1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Terhorst D, Koti I, Krause K, Metz M, Maurer M. In chronic spontaneous urticaria, high numbers of dermal endothelial cells, but not mast cells, are linked to recurrent angioedema. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;43:131‐136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials