Abstract

Health care systems in England and the United States are under similar pressures to provide higher quality, more efficient care in the face of aging populations, increasing care complexity, and rising costs. In 2010 and 2011, major strategic reports were published in the two countries with recommendations for how to strengthen their respective nursing workforces to address these challenges. In England, it was the 2010 report of the Prime Minister’s Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery, Front Line Care: The Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England. In the United States, it was the Institute of Medicine’s report The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. The authors of both reports recommended shifting entry level nursing education to the baccalaureate degree and building capacity within their educational systems to prepare nurses as leaders, educators, and researchers. This article will explore how, with contrasting degrees of success, the nursing education systems in the United States and England have responded to these recommendations and examine how different regulatory and funding structures have hindered or enabled these efforts.

Keywords: nursing staff, capacity building, education, nursing

In 2010 and 2011, major reports were published in England and the United States calling for robust investment in nursing education as a key strategy to strengthen nurse workforces and improve health care systems. In England, it was the Prime Minister’s Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England’s (2010) report Front Line Care: The Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England, and in the United States, it was the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM, 2011) report The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. The authors of both reports, recognizing the need to prepare their workforces to address the growing complexities of health care, advocated shifting entry level nursing education to the baccalaureate degree, and building capacity within their educational systems to prepare nurses as leaders, educators, and researchers. Despite the similar recommendations, national responses to these two reports have been quite different. England has now transitioned to the baccalaureate degree requirement for entry to practice, but its government-controlled education system continues to struggle with budgetary constraints and actually cut nurse training places in the years following the Front Line Care report, contributing to a severe ongoing nurse shortage (Migration Advisory Committee, 2016). The United States, by contrast, has not fully transitioned to the baccalaureate degree. However, the Future of Nursing report added momentum to an already significant growth trend in baccalaureate graduates that started in the early to mid-2000s and was driven largely by private market forces (Buerhaus, Auerbach, & Staiger, 2014, 2016). The contrast in national responses to these two reports provides an informative lesson for how the structure of a country’s nursing education system affects capacity to build and strengthen nurse workforces. This article reviews background and context for the Front Line Care and Future of Nursing reports, examines major actions that have taken place in the two countries following the reports, and considers future implications for nursing policy and practice.

Methods

The article is based on a review of reports, policy papers, and other materials from government sources, advisory groups, and professional associations in England and the United States. Documents were found through online searches and citation mining of other reports, policy papers, and news articles. In addition, websites of key stakeholders such as the National Health Service (NHS) in England, the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) were searched. To supplement these primary sources, a literature search of PubMed was done using the following terms: nurse, staffing, education, bachelor of science, baccalaureate, workforce, shortage, Brexit, Affordable Care Act (ACA), and health reform. Lay press articles were also reviewed to understand contemporary public responses to some of the issues discussed. The period of analysis for this article is primarily from 2010 to 2017; however, historical events are referenced as necessary to provide background and context.

Background and Context

Overview of Nursing Education in England and the United States

England

To appreciate the recommendations of the Future of Nursing and Front Line Care reports, one must first understand some basic differences in nursing education between the two countries (see Table 1). In England, the Nursing and Midwifery Council, an independent regulatory body, sets education and training standards, as well as oversees licensure for the entire country. When Front Line Care was published in March 2010, two educational tracks were approved for entry to practice: the baccalaureate degree and diploma. In September 2010, the Nursing and Midwifery Council updated its education standards to require the baccalaureate degree for new nurses as of 2013.

Table 1.

Differences in Entry-Level Nursing Education Between England and the United States.

| England | United States | |

|---|---|---|

| Educational pathways available (as of 2017) | Baccalaureate degree (3-year full-time program)a | Baccalaureate degree (4-year full-time program)a Associate degree Diploma |

| Regulatory oversight of nursing education programs | Nursing and Midwifery Council | State Boards of Nursing Accreditation through a U.S. Department of Education-approved accrediting agency required to be eligible for federal student financial aid funding. |

| Key governmental funding streams for entry-level nursing education |

Prior to August 2017: NHS bursary system pays tuition and fees for all students. Administered by Health Education England. After August 2017: Student loan system. Administered by Health Education England. |

Title VIII, Public Health Service Act: Nursing Workforce Development Programs. Administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration. Title IV, Higher Education Act: Includes a number of federal grants, loans, and work-study programs. Not specific to nursing. Administered by the U.S. Department of Education. Carl D. Perkins Vocational and Technical Education Act: Funding for associate degree nursing programs. Administered by the U.S. Department of Education. Medicare: Graduate Medical Education funding for hospital diploma programs. Administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. |

| Private funding for nursing education | Limited private scholarships and loan forgiveness programs are available. | Many private scholarships and loan forgiveness programs are available. Many employers offer tuition support |

Many schools in both England and the United States offer accelerated programs for students who already hold a baccalaureate degree in another discipline.

Nursing education is publicly controlled and funded by Health Education England, a division of the country’s Department of Health that is closely aligned with the NHS. This centrally controlled nursing education system supports the NHS where 81% of all English nurses work (RCN, 2016a). As of September 2017, NHS England employed approximately 318,000 nurses (NHS Digital, 2017). Nurses outside the NHS work in private, charity, or other public sectors (RCN, 2016a).

Until August 2017, all English nursing students received non means tested NHS bursary funding to pay for tuition and fees at educational institutions approved by the Nursing and Midwifery Council. Health Education England determines capacity for this publicly funded system by setting the number of training places commissioned each year. This annual cap on training places has been a major limiting factor to increasing nursing graduates to boost supply (Migration Advisory Committee, 2016; RCN, 2016a). As of August 2017, in an effort to eliminate the cap and increase enrollment capacity for schools, Health Education England and the NHS replaced the bursaries (subsidies) with a student loan program (Department of Health, 2016). Implications of this decision are discussed later.

United States

In the United States, nursing education and licensure are regulated at the state level by state boards of nursing. As of 2016, approximately 2.9 million registered nurses worked in the country across an array of private and public hospitals and other clinical settings (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). Three major education pathways are approved for entry to practice: baccalaureate degree, associate degree, and diploma. Students must graduate from a Board of Nursing-approved education program in order to qualify to take the NCLEX-RN, the national licensure exam for registered nurses. Most schools also voluntarily apply for accreditation from one of the U.S. Department of Education’s approved accrediting agencies in order to demonstrate commitment to high-quality standards and be eligible for federal student financial aid programs (U.S. Department of Education, 2017).

Federal funding for undergraduate nursing education is available through two primary funding streams: Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (2008) and Nursing Workforce Development Programs under Title VIII of the Public Health Service Act of 1944 (2010). These funding sources offer a variety of loans, grants, scholarships, and loan forgiveness programs. Additional federal funding is available to associate degree programs under the Carl D. Perkins Act of 1984 (2006) and to hospital diploma programs with Medicare Graduate Medical Education dollars (AACN, 2015b). According to a 2012–2013 survey done by the AACN, 75.8% of undergraduate nursing students relied on federal funding to cover at least part of their education costs, while the remainder of costs were covered through private loans, personal or family income, private scholarships, employer tuition support, or other sources (AACN, 2013).

This decentralized system of funding and regulation of nursing education is substantially different from the English system. It is also reflective of the decentralized, mixed private–public structures of the U.S. health care system overall. There is no national body that sets enrollment capacity for nursing schools based on central budgetary constraints, as there is in England. The primary obstacles limiting capacity for increasing enrollment in nursing schools are faculty shortages and lack of clinical placements (National League for Nursing, 2016). While the U.S. nursing educational system has more flexibility to expand to meet demand than its English counterpart, its complicated financial and regulatory structures have historically served as barriers to unified national workforce planning (Ricketts & Fraher, 2013).

Evidence and Changing Demand for Nurses

The Future of Nursing and Front Line Care recommendations were based on a large body of evidence which has shown that patients fare better when nurses are educated at the baccalaureate level (Aiken, Clarke, Cheung, Sloane, & Silber, 2003; Aiken et al., 2014, Kutney, Sloane, & Aiken, 2013; Yakusheva, Lindrooth, & Weiss, 2014) and present in clinical settings in sufficient numbers (Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Sochalski, & Silber, 2002; Aiken et al., 2014; Kane, Shamliyan, Mueller, Duval, & Wilt, 2007; Needleman, Buerhaus, Mattke, Stewart, & Zelevinsky, 2002; Needleman et al., 2011; Rafferty et al., 2007). The reports came at a time of major debates in both England and the United States over how best to reform health care systems to address growing costs, aging populations, and increasing patient complexity. These health care reform efforts have significantly changed demand for nurses, who now must take on greater roles in population health, care coordination, disease prevention, health promotion, and interprofessional collaboration (Fraher, Spetz, & Naylor, 2015; RCN, 2015a).

In the United States, the ACA was passed in 2010. The law expanded Medicaid and created federal and state-subsidized individual insurance marketplaces to reduce the number of uninsured. It also created new payment and care delivery models, such as accountable care organizations, and contained many measures to reward health care organizations for quality (Kocher, Emanuel, & DeParle, 2010). These initiatives increased the population of Americans seeking care and stimulated changes in health care systems to emphasize quality and value.

Around the same time the ACA was being debated in the United States, policymakers, NHS leaders, and advocacy groups in England were discussing how to better integrate health care and social services to accommodate the increasingly complex needs of patients (Department of Health, 2013). This led to the NHS creating the National Collaboration for Integrated Care and Support in 2013 and designating several pioneer sites to test new integrated care delivery models (NHS England, 2015a). As in the United States, these reform efforts have increased the need for nurses to assume enhanced roles and strengthen their abilities to collaborate within team-based care models (Department of Health, 2013; Ricketts & Fraher, 2013).

England: Front Line Care Report

Report and Response

The 2010 Front Line Care report was the final product of the Prime Minister’s Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England. In it, the Commission supported the move from the diploma to baccalaureate degree as the new standard for entry to practice by 2013. It emphasized the need to support graduate nursing education and increase the number of nursing and midwifery faculty to meet capacity. The report also dealt with strengthening nurse leadership, regulatory issues, nurses’ responsibilities to the public, culture change, and addressed the issue of nursing’s poor societal image, suggesting a need to counter myths and “market nursing and midwifery as careers” (p. 92).

In 2010, the Nursing and Midwifery Council updated its education standards to require all nursing education programs to be at the baccalaureate level as of 2013 (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2010). The Department of Health’s (2011) response to the Front Line Care report supported the move to the baccalaureate degree but provided no concrete commitment for building capacity within the nursing education system. Anne Milton, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Public Health, wrote:

The country is facing very challenging financial times and Front Line Care now has to be read in this new context where funding increases are limited but where expectations of nurses and midwives delivering the very best care remain as high as ever. Much of what we now have to do heralds a change of culture rather than a need for new funding. (Department of Health, 2011, p. 5)

Here is where the government’s central control over nurse education and thus, supply of nurses, becomes evident. The NHS was hit hard by the 2008–2009 global recession and postrecession period (Appleby, Crawford, & Emmerson, 2009). In an effort to constrain spending, the NHS decreased nurse staffing and reduced skill mix in several trusts, or health care organizations within the NHS (Audit Commission, 2010). And Health Education England cut nurse training places starting in the 2009/2010 financial year, reaching a 10-year low in 2012/2013, despite a recession-driven surge in applicants to university nursing programs (RCN, 2015a; Figure 1). Although the number of training places have started to increase again, there were still 2,812 fewer training places in 2015/2016 than there were in 2005/2006 (RCN, 2015a).

Figure 1.

Annual number of commissioned nurse training places in England in the years prior to and after the 2010 Front Line Care Report.

Data source: Health Education England (2016b).

Nursing Shortage and Concerns Over Poor Staffing in the NHS

The nurse vacancy rate in NHS England was 9.4% in 2016, almost twice that of the maximum 5% vacancy recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), an independent body in charge of providing guidance for care quality to the NHS (Migration Advisory Committee, 2016). The government’s Migration Advisory Committee has identified the cuts in training places between 2009 and 2013 as a major contributing factor to the current shortage (Migration Advisory Committee, 2016). This committee is responsible for determining which occupations qualify for shortages to be given priority for work visas. The United Kingdom’s planned withdrawal from the European Union (EU), familiarly known as Brexit, has further threatened nurse supply because of its anticipated impact on EU immigration restrictions. Even before separation occurs, the number of EU nurses newly admitted to the Nursing and Midwifery Council register in the United Kingdom dropped from 9,389 in 2015/2016 to 6,382 in 2016/2017. Moreover, 32% of EU nurses leaving the register reported doing so because of Brexit (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2017). In England, EU nurses make up 4.5% of the total nursing workforce, but several NHS trusts employ 10% or more of their nurses from the EU, meaning that those trusts could be particularly vulnerable to staffing shortages (Marangozov, Williams, & Bevan, 2016).

In 2013, nurse shortages in the NHS gained considerable public attention after the Secretary of State for Health commissioned four independent inquiries to investigate reports of inadequate staffing and poor care across several NHS trusts. The precipitating event was a scandal in which the Mid-Staffordshire Trust was found to have had high mortality rates and many reports of poor care from the late 2000s to early 2010s. The Francis Inquiry (2013) concluded that the causes of these deficiencies included the following: understaffing of nurses, poor work environments, bullying, mistake hiding, and a culture of cost-cutting and target chasing. It also found that nursing skill mixes were being diluted with nonregistered auxiliary staff due to the shortage of registered nurses. Other inquiries followed and found similar findings across multiple hospital trusts in the NHS (Berwick, 2013; Cavendish, 2013; Keogh, 2013).

Safe Staffing Debates

Following the earlier inquiries, NICE was commissioned with the task of reviewing the evidence around nurse staffing and providing recommendations for different patient areas in the NHS. It published staffing guidelines for adult acute wards in July 2014 and maternity settings in February 2015. With both sets of guidelines, NICE stopped short of recommending minimum nurse-to-patient ratios across the board but instead provided formulae and guidance for individual hospitals and units to determine their own staffing needs (NICE, 2014, 2015). NICE was working on guidelines for emergency, mental health, and community settings, when in June 2015, the Department of Health asked it to suspend its work so that it could be taken over by NHS Improvement, a quality improvement agency within the NHS (NICE, 2016). This move was criticized by nurse leaders and patient safety groups who feared that, rather than accepting NICE’s independent, evidenced-based recommendations, the NHS would dilute the guidelines to avoid having to respond to minimum staffing recommendations that would prove unaffordable (Campbell, 2015; Oliver, 2016).

NHS Improvement (2016, 2017a, 2017b) subsequently released staffing improvement tools for mental health, learning disabilities, and community health settings in 2016 and 2017. While the RCN praised these resources as being practical and pragmatic, it also expressed concern that the tools were too generic and lacked the teeth to have significant impact (RCN, 2017a, 2017b, 2017c). Although nurse staffing in acute wards has improved in response to the Francis report and staffing guidelines, it has been at the expense of cuts in mental health, learning disabilities, community nursing, and senior nurse positions (RCN, 2014, 2016a). This suggests that unless the overall capacity for nurses within the NHS is strengthened, there will always be compromises on safe staffing. While staffing needs are ultimately determined by NHS commissioners and managers at the local level, safe staffing is still contingent on having a secure and stable national supply of nurses. As the RCN argued in its 2013 labor market review, “local application of staffing tools is irrelevant if there are insufficient nurses, with the right skills, available to be deployed locally” (p. 5).

Culture Change

Under Secretary Milton’s call for “a change of culture rather than a need for new funding” (Department of Health, 2011, p. 5) illustrates that the Department of Health prioritized NHS culture change over financial investment in nursing education in response to Front Line Care. This was also evident in Health Education England’s cuts in training places for 3 years after the report (RCN, 2015a). Since 2011, much attention has been focused on building a more caring and compassionate culture in the NHS, but it is unclear how effective these efforts have been. The 2013 Francis Inquiry report suggested that nurses should take an aptitude test prior to licensure “to explore the candidate’s attitude towards caring, compassion, and other necessary professional values” (p. 77). It also recommended that nurses on an annual basis “be required to demonstrate their ongoing commitment, compassion, and caring shown towards patients” (p. 78). The NHS has developed this into a strategic vision called the “6 Cs”care, compassion, competence, communication, courage, and commitment (NHS England, 2015b).

The problem with this strategy is that it places blame on nurses for not being compassionate enough and diverts resources to a questionably effective culture change effort, without addressing the underlying problems of inadequate supply and understaffing. In a study of 12 European countries, English nurses had the highest rates of job-related burnout second only to Greece, which has a health care system in crisis (Aiken, Rafferty, & Sermeus, 2014). Burnout is a measure of emotional exhaustion and is linked to patient safety outcomes (Laschinger & Leiter, 2006). Seventy-three percent of nurses surveyed in Aiken, Rafferty, et al.’s (2014) study said that they did not have enough registered nurses on staff to provide quality patient care, and 64% said that they lacked adequate support services to spend time with patients. These findings suggest that a perceived lack of compassion in the NHS is more likely a symptom of an underresourced, overstretched nursing workforce, rather than a deficit in organizational culture.

The United States: The Future of Nursing Report

Report and Response

The IOM, in conjunction with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), released its Future of Nursing report in 2010 and published it in 2011. Its authors called for nurses to play a fundamental role in the transformation of the U.S. health care system. The report contained eight recommendations that included measures to strengthen nursing education and training, remove scope of practice barriers for advanced practice nurses, prepare nurses with the skills needed to take on leadership roles, and improve the quality of health care workforce data. Two of the key recommendations were to increase the proportion of nurses with baccalaureate degrees in the United States from 50% to 80%, and double the number of nurses with doctorates by 2020. For these last two recommendations, the IOM outlined specific steps for accrediting bodies, academic nurse leaders, public and private funders, and employers to take in order to ensure funding, increase enrollment, monitor progress, and increase diversity in the workforce (IOM, 2011).

Following the release of the IOM report, RWJF and AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons) launched The Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action to oversee implementation of the report’s recommendations and monitor progress. The campaign is housed within AARP’s Public Policy Institute in the Center to Champion Nursing in America, which was created in 2007 with a $10 million grant from RWJF (Campaign for Action, 2017). It has helped establish action coalitions in every state and the District of Columbia to coordinate work with policymakers, health care professionals, educators, and business leaders (Campaign for Action, 2017). In contrast to Front Line Care, which was government commissioned, the IOM (now called the National Academy of Medicine), AARP, and RWJF are all nongovernmental organizations. Whereas Front Line Care has not received much attention since the initial responses following its publication (Department of Health, 2011; Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2010), AARP and RWJF’s private investments have helped the Future of Nursing campaign to endure as an ongoing active strategic framework for workforce planning (IOM, 2015).

Growth in Baccalaureate Nursing Graduates and Overall Nurse Supply

After a significant nursing shortage in the early 2000s, the number of baccalaureate and associate degree graduates surged from 77,000 in 2002 to just over 200,000 in 2014 (Buerhaus et al., 2016). This remarkable turnaround was stimulated by several national recruitment initiatives to promote nursing as a career, slow job recovery in nonhealth care sectors after the 2001 and 2008–2009 recessions, and a growing health care economy (Auerbach, Staiger, Muench, & Buerhaus, 2013). Still, future projections for nurse supply over the next decade remain mixed due to uncertainty in how emerging models of care will affect demand moving forward, and whether growth in school enrollments will continue at the current pace (Auerbach, Buerhaus, & Staiger, 2015a; Health Resources and Services Administration, 2014).

Although enrollment has increased in both associate and baccalaureate degree programs, the most dramatic growth has been in the latter. This trend began in the early 2000s and was driven by private market demand from employers preferentially hiring baccalaureate nurses, health care reform efforts (Buerhaus et al., 2016), and increasing innovation in accelerated and degree-completion programs to attract a wider pool of students (Auerbach et al., 2013). The Future of Nursing report fueled this growth (Buerhaus et al., 2016). Baccalaureate programs have steadily increased the number of students accepted, more than doubling from approximately 55,000 in 2005 to 119,000 in 2015 (AACN, 2006, 2015a; Figure 2). In 2011, for the first time, the annual number of baccalaureate graduates exceeded the number of associate degree graduates (Buerhaus et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

Annual gross number of acceptances to baccalaureate nursing programs in the United States in the years prior to and after the Future of Nursing report was released in 2010 (published in 2011).

Data source: American Association of Colleges of Nursing annual reports. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/publications/annualreports

Despite the growth in baccalaureate nursing graduates, the proportion of nurses with a baccalaureate degree or higher in the workforce overall is still far short of the Future of Nursing goal of 80%. According to Spetz (2017), 53.2% of nurses in the United States held at least a baccalaureate degree in 2015. However, there is significant variation across the 50 states, ranging from 38.3% in Wyoming to 69.8% in Nebraska. Hence, while there have been substantial improvements in the educational pipeline to prepare nurses with baccalaureate degrees, there is still a considerable way to go to transform the overall U.S. nursing workforce.

The ACA and the 2016 Presidential Election

The ACA heightened demand for jobs in the health care sector (Frogner, Spetz, Parente, & Oberline, 2015) and contained several provisions to support nursing education. Most notable was the reauthorization of the Title VIII Nursing Workforce Development Programs under the Public Health Service Act (ACA, 2010). Title VIII programs are the largest source of federal funding of nursing education and are prioritized for baccalaureate and graduate nursing education (AACN, 2010). The ACA expanded and modernized all major Title VIII programs including Advanced Education Nursing grants, Workforce Diversity grants, Nurse Education, Practice and Retention grants, the Nurse Faculty Loan Program, Comprehensive Geriatric Education grants, and the National Nurse Service Corps. It also created a new Graduate Nurse Education Demonstration to use Medicare dollars to support clinical education of advanced practice nurses at five hospitals over 4 years (ACA, 2010).

The momentum behind the ACA changed significantly after the 2016 presidential and congressional elections when Republicans won control of both the White House and Congress after a long campaign to “repeal and replace” the ACA. Republican efforts to overturn the law have, as of January 20, 2018, been unsuccessful. Nonetheless, in December 2017, Congress did repeal the ACA’s individual mandate requiring all U.S. taxpayers to have health insurance as part of its tax reform bill (Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, 2017). The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office has estimated that this repeal will increase the number of uninsured people by 13 million by 2027 (Congressional Budget Office, 2017). It is uncertain how the elimination of the individual mandate will affect demand for nurses moving forward.

President Donald J. Trump’s 2018 budget proposed eliminating $403 million in health professions and nursing training programs (Office of Management & Budget, 2017). This included a $146 million cut to Title VIII funding that would eliminate all Nursing Workforce Development programs with the exception of the National Nurse Service Corps (AACN, 2017). The budget also proposed cutting the Bureau of Health Professions—the agency responsible for overseeing workforce research, planning, and funding—by $455 million, or 85% from fiscal year 2017 to 2018 (AACN, 2017). The American Nurses Association (ANA, 2017) strongly opposed the budget, arguing that the proposed cuts would “drastically [hamper] efforts to address critical faculty shortages and recruit new nurses into the profession.”

As of January 20, 2018, Congress has yet to pass a budget for federal fiscal year 2018, so it is unclear to what degree these programs will be ultimately funded. Legislation with bipartisan support has been introduced in both the Senate and House of Representatives to update and continue funding for Title VIII Nursing Workforce Development programs through fiscal year 2022 (H.R. 959, 2017; S.1109, 2017). Although the future of Title VIII funding remains unclear, there is no doubt that national political shifts have significant influence over efforts to fund nursing education and workforce development programs.

Implications for Policy and Practice

It is beyond the scope of this article to examine the direct effects of the Front Line Care and Future of Nursing reports on subsequent policies and actions affecting nursing education and workforce planning in England and the United States. Many factors influence policy decisions, and no single report can serve as an ultimate framework. Rather, the goal of this article is to understand factors that have helped or hindered leaders’ abilities in the two countries to respond to the similar strategic recommendations in those reports. The comparisons and analyses presented here show that national efforts to transform and strengthen nursing education must be paired with policies to build and maintain a stable domestic supply of nurses. A few key lessons can be learned.

School Enrollment Capacity Is a Key Determinant of Nurse Supply

Nursing school enrollment capacity in both the United States and England is limited by shortages of faculty and clinical placement sites (National League for Nursing, 2016; RCN, 2015b). In 2013, baccalaureate nursing programs in the United States received 259,150 applications and accepted 104,864, for an acceptance rate of 40.5% (AACN, 2014). In the United Kingdom that same year, baccalaureate programs received 226,400 applications but accepted 24,700, an acceptance rate of 10.9% (RCN, 2014).1 Although these figures are for the United Kingdom overall, England accounted for approximately 80% of the training places in the United Kingdom in 2013 (RCN, 2014) and thus is largely driving this number. While the acceptance rate in the United States is considerably higher, schools in the United States still turned away almost 58,000 qualified applicants in 2013 (AACN, 2015a).

To build capacity within schools, efforts must continue to support nurses’ pursuit of graduate education to become faculty. In the United States, this means that nurses need to push Congress to reauthorize Title VIII Nursing Workforce Development programs, including the Nurse Faculty Loan Program and Advanced Education Nursing grants. The Trump administration has proposed eliminating both of these programs out of “lack of evidence that they significantly improve the Nation’s health workforce” (Office of Management & Budget, 2017, p. 22). The National League for Nursing, AACN, state action coalitions, and other professional associations should continue to educate legislators and communicate updates on progress, to prevent such cuts from occurring. Nurses and their professional associations should also advocate for renewal and expansion of the Graduate Nurse Education Demonstration and continued support of the National Institutes of Health, which support PhD education for nurses.

In England, the biggest constraint on enrollment capacity has been Health Education England’s centrally imposed annual cap on training places. Despite a surge in the number of applicants to nursing schools during and after the 2008–2009 recession, its publicly funded bursary system could not expand to take advantage of this–—instead, Health Education England actually cut training places between 2009 and 2013 (RCN, 2014). By contrast, the mixed private–public funding mechanisms that finance nursing education in the United States provided flexibility for schools to expand to accept more students, making the recession and postrecession years a time of significant growth in enrollments (Buerhuas et al., 2014). To eliminate the annual cap on training places, Health Education England in August 2017 switched from the public bursaries to a student loan system (Department of Health, 2016). Since the change was first announced in 2015, the Nursing and Midwifery Council has seen an increase in applications from schools applying to become approved education institutions, as well as from schools offering nontraditional programs including part-time pathways, work-based models, and nurse apprenticeships (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2017). However, many nurse leaders, educators, and legislators have expressed concern that, rather than boosting enrollments as intended, the move to student loans will deter potential students from entering the nursing profession (House of Commons, 2016).

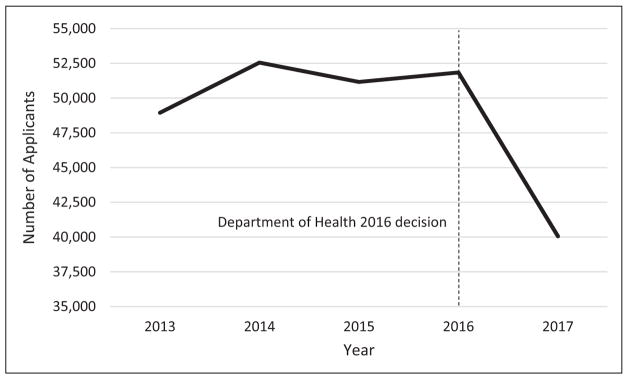

Shifting Cost of Education to Students Carries Consequences

Most English nursing graduates work in the NHS, where salaries are already capped. Moreover, there has been no discussion of increasing salaries to offset loan repayment costs (House of Commons, 2016). Thus, loan repayments could essentially become pay cuts for all new nurses entering the profession. After fairly stable application rates to English university nursing programs in 2015 and 2016, the number of applicants in 2017—the year the student loan system took effect—decreased 23% from 43,800 to 33,810 (Universities and Colleges Admissions Service, 2017; Figure 3). This 1 year of application data provides limited evidence, yet, it suggests that the shift to student loans may already be deterring potential applicants.

Figure 3.

English applicants to university nursing programs in the years before and after the Department of Health’s 2016 decision to switch from bursaries to student loans.

Data source: Universities and Colleges Admissions Service. (2017). Summary statistics of nursing applicants. Retrieved from https://www.ucas.com/file/115961/download?token=n9lk8cCN

Nurses in the United States have long relied on student loans to pay for their education, but they are also paid higher salaries than nurses in England, thus offsetting loan repayment costs. As of 2015, nurses in the United States earned on average 30% more than the national wage, whereas nurses in the United Kingdom earned only 10% more than the national average wage (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2015). The United States has also seen more market-based adjustments of nursing salaries in areas of the country with higher costs of living, such as the East and West Coasts (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). In England, by contrast, costly urban locations like London have faced severe nursing shortages due to nurses being unable to afford the cost of living (RCN London, 2015). As Health Education England transitions to the student loan system, the NHS Pay Review Body needs to determine how the NHS might respond with regard to nursing wages. The Migration Advisory Committee (2016) identified pay as a “lever at the disposal of public sector employers to moderate shortages” (p. 3) and noted that substantial pay increases were used to abate shortages in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But thus far there has been no sign that wage increases are being considered (Migration Advisory Committee, 2016).

Strategic Workforce Planning Must Be Aligned With Funding and Regulatory Mechanisms

The Nursing and Midwifery Council and Health Education England’s central regulatory and financial control over England’s nursing education system has enabled a smoother transition to the baccalaureate degree than has occurred in the United States. The Nursing and Midwifery Council is the sole body to set education standards in the country, and Health Education England only pays for training at institutions approved by the Nursing and Midwifery Council. However, this achievement has been overshadowed somewhat by Health Education England’s introduction of a new support worker in 2015 called the “nursing associate” (Health Education England, 2016a), which is comparable to a licensed practical nurse in the United States. England previously had a role similar to this called the enrolled nurse, but that position was phased out in the 1990s over quality concerns (Francis & Humphreys, 1999). This policy seems inconsistent with efforts to strengthen the workforce through education and appears to be an attempt to stretch the workforce with less qualified staff. The RCN has expressed concern that this new role is being “driven by efficiency savings and will result in cheaper, but not necessarily safer or more effective care” (RCN, 2016b. 6).

The United States still lags behind England in requiring the baccalaureate degree for entry to practice. In 2017, New York became the first and only state to pass legislation that would require all new registered nurses to obtain a baccalaureate degree within 10 years of initial licensure (S6768, 2017). This will take effect after a state commission has had time to review and address barriers for entry into baccalaureate nursing programs. In contrast to England, the U.S. nursing educational system functions within a complex regulatory and financial network of state boards of nursing, different accrediting bodies, and many public and private funding sources, making uniform policy implementation difficult. Much of the push toward baccalaureate nursing education in the United States has been driven from the private sector by employers, professional associations, universities, and initiatives from RWJF, AARP, and others. While this has allowed for vital investment in nursing education from outside the global budget constraints of the federal government, it has also contributed to the decentralization of coordinated workforce planning (Ricketts & Fraher, 2013).

Federal funding mechanisms for nursing education in the United States should support the Future of Nursing strategic recommendations. Medicare still has mandatory funding streams to pay for hospital diploma nursing programs, even though only 2.3% of nursing programs remain at the diploma level (AACN, 2015b). And, the Department of Education still spends billions of dollars annually supporting associate degree programs with Title IV and Carl D. Perkins funding (Aiken, 2011). In a labor market where employers preferentially hire baccalaureate nurses, associate degree graduates are at a disadvantage (Auerbach, Buerhaus, & Staiger, 2015b). Many will return to school for additional education, a burden of both time and money to the individual nurse. Accrediting bodies, schools, professional associations, and legislators need to continue work in modernizing these funding sources to support associate degree and diploma schools in academic progression models to transition to the baccalaureate degree.

Conclusions

Comparisons between England and the United States are useful because they help to illustrate strengths and weaknesses in workforce planning in the two countries. The Future of Nursing and Front Line Care reports were written in response to similar challenges. Health care systems in both England and the United States were and continue to be under growing pressure to improve the quality and efficiency of care in the face of aging populations and increasing care complexity. To meet these challenges, political and nursing leaders in both countries recognized the need to strengthen their nursing workforces by investing in nursing education.

England’s centrally controlled, publicly financed nursing education system has transitioned more easily to the baccalaureate degree for entry to practice than the state regulated, public and privately financed education system in the United States. However, the English system has also been more constrained in its capacity to expand to meet rising demand. Mixed private and public funding mechanisms have afforded the U.S. educational system with greater flexibility to grow in size. But this fragmented financing in addition to complex regulatory structures have made uniform transformation to the baccalaureate degree much harder in the United States. In both countries, complex regulatory, economic, and political forces have challenged the abilities of policymakers, educators, health system administrators, and nurse leaders to influence change. A comparative analysis of how these challenges have been faced in the two countries makes one thing clear: that efforts to strengthen the nursing workforce through improvements in education must be aligned with policies to produce and maintain an adequate domestic supply of nurses.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Dr. Linda Aiken and Dr. Matthew McHugh for their assistance in review of early manuscript drafts.

Funding

The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work is supported by an NINR training grant awarded to the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing (T32-NR-007104).

Biography

Elizabeth White is a predoctoral fellow in the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Footnotes

2013 data are used here because it is the last year in which both AACN and the UK’s Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) reported applications, allowing for comparison. In 2014, UCAS switched to reporting applicants. The UCAS 2013 data are no longer available on its website, so I am referencing those data as published in the RCN 2014 labor market review, which only reports figures for the United Kingdom overall, not England specifically.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aiken LH. Nurses for the future. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(3):196–198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Cheung RB, Sloane DM, Silber JH. Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1617–1623. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Rafferty AM, Sermeus W. Caring nurses hit by a quality storm. Nursing Standard. 2014;28(35):22–25. doi: 10.7748/ns2014.04.28.35.22.s26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, Van den Heede K, Griffiths P, Busse R, … Sermeus W. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: A retrospective observational study. The Lancet. 2014;383(9931):1824–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62631-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Annual report 2006. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Publications.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: AACN’s overview of supported provisions and sections requiring attention. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Publications.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Title VIII student recipient survey summary report. Policy Brief. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/government-affairs/archives/2013/archives.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Annual report 2014. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Publications.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Annual report 2015. 2015a Retrieved from http://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Publications.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Medicare at 50: A look at nursing education. 2015b Retrieved from http://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Policy/Newsletters/Inside%20Academic%20Nursing/September-2015.pdf.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Fiscal year 2018 appropriations. 2017 Retrieved from http://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Publications.

- American Nurses Association. ANA opposes President Trump’s 2018 budget proposal. 2017 Mar 16; (Press release). Retrieved from http://nursingworld.org/FunctionalMenuCategories/MediaResources/PressReleases/ANA-Opposes-President-Trumps-2018-Budget-Proposal.html.

- Appleby J, Crawford R, Emmerson C. How cold will it be? Prospects for NHS funding: 2011–2017. 2009 Jul; Retrieved from The King’s Fund website: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/how-cold-will-it-be.

- Audit Commission. Making the most of NHS frontline staff. 2010 Jun; Retrieved from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150423154441/http://archive.audit-commission.gov.uk/auditcommission/aboutus/publications/pages/national-reports-and-studies-archive.aspx.html.

- Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI, Staiger DO. Will the RN workforce weather the retirement of the baby boomers? Medical Care. 2015a;53(10):850–856. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI, Staiger DO. Do associate degree registered nurses fare differently in the nurse labor market compared to baccalaureate-prepared RNs? Nursing Economics. 2015b;33(1):8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach DI, Staiger DO, Muench U, Buerhaus PI. The nursing workforce in an era of health care reform. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(16):1470–1472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1301694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick D. A promise to learn—A commitment to act: Improving the safety of patients in England. Report of the National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/berwick-review-into-patient-safety.

- Buerhaus PI, Auerbach DJ, Staiger DO. The rapid growth of graduates from associate, baccalaureate, and graduate programs in nursing. Nursing Economics. 2014;32(6):290–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerhaus PI, Auerbach DI, Staiger DO. Recent changes in the number of nurses graduating from undergraduate and graduate programs. Nursing Economics. 2016;34(1):46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wages: Registered nurses. 2016 May; Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291141.htm.

- Campaign for Action. RWJF and AARP: Allies in supporting nursing. 2017 Retrieved from https://campaignforaction.org/about/leadership-staff/the-rwjf-and-aarp-partnership/

- Campbell D. NHS patient safety fears as health watchdog scraps staffing guidelines. The Guardian. 2015 Jun 4; Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/jun/04/nhs-patient-safety-fears-nice-scrap-staffing-levelguidelines-mid-staffs-scandal.

- Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 1984, 20 U.S.C. § 2301 et seq. (2006).

- Cavendish C. An independent review into healthcare assistants and support workers in the NHS and social care settings. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/236212/Cavendish_Review.pdf.

- Congressional Budget Office. Repealing the individual health insurance mandate: An updated estimate. 2017 Nov; Retrieved from https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53300.

- Department of Health. The government’s response to the recommendations in Frontline Care: The Report of the Prime Minister’s Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England. 2011 Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215665/dh125985.pdf.

- Department of Health. Integrated care: Our shared commitment. 2013 May 13; Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/integrated-care.

- Department of Health. NHS bursary reform. 2016 Apr 7; Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-bursary-reform/nhs-bursary-reform.

- Fraher E, Spetz J, Naylor M. Nursing in a transformed health care system: New roles, new rules. Research brief. 2015 Jun; Retrieved from Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics website: https://ldi.upenn.edu/brief/nursing-transformed-health-care-system-new-roles-newrules.

- Francis B, Humphreys J. Enrolled nurses and the professionalisation of nursing: A comparison of nurse education and skill mix in Australia and the UK. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1999;36(2):127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(99)00006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/report.

- Frogner BK, Spetz J, Parente ST, Oberlin S. The demand for health care workers post-ACA. International Journal of Health Economics and Management. 2015;15(1):39–151. doi: 10.1007/s10754-015-9168-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Education England. Building capacity to care and capability to treat: A new team member for health and social care in England. 2016a Retrieved from https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Response%20to%20Nursing%20Associate%20consultation%2026%20May%202016.pdf.

- Health Education England. HEE commissioning and investment plan—2016/2017. 2016b Retrieved from https://hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/HEE%20commissioning%20and%20investment%20plan.pdf.

- Health Resources and Services Administration. The future of the nursing workforce: Nationaland state-level projections, 2012–2025. 2014 Dec; Retrieved from http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/supplydemand/nursing/workforceprojections/nursingprojections.pdf.

- Higher Education Act of 1965, 20 U.S.C. § 1070 et seq. (2008).

- House of Commons. NHS bursary, e-petition 113491. UK Parliamentary debates. 2016 Jan 11;604 Retrieved from https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/113491. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. 2011 Retrieved from http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2010/The-Future-of-Nursing-Leading-Change-Advancing-Health.aspx.

- Institute of Medicine. Assessing progress on the Institute of Medicine report The Future of Nursing. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2015/Assessing-Progress-on-the-IOM-Report-The-Future-of-Nursing.aspx.

- Kane RL, Shamliyan TA, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt TJ. The association of registered nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: Systematic review and metaanalysis. Medical Care. 2007;45(12):1195–1204. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181468ca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh B. Review into the quality of care and treatment provided by 14 hospital trusts in England: Overview report. NHS Report. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.nhs.uk/nhsengland/bruce-keogh-review/documents/outcomes/keoghreview-final-report.pdf.

- Kocher R, Emanuel EJ, DeParle NAM. The Affordable Care Act and the future of clinical medicine: The opportunities and challenges. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;153(8):536–539. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-8-201010190-00274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutney-Lee A, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. An increase in the number of nurses with baccalaureate degrees is linked to lower rates of postsurgery mortality. Health Affairs. 2013;32(3):579–586. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger HKS, Leiter MP. The impact of nursing work environments on patient safety outcomes: The mediating role of burnout engagement. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2006;36(5):259–267. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200605000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marangozov R, Williams M, Bevan S. Beyond Brexit: Assessing key risks to the nursing workforce in England. IES paper. 2016 Retrieved from Institute of Employment Studies website: http://www.employment-studies.co.uk/resource/beyond-brexit-assessing-key-risks-nursing-workforce-england.

- Migration Advisory Committee. Partial review of the shortage occupation list: Review of nursing. 2016 Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/migrationadvisory-committee-mac-partial-review-shortage-occupation-list-and-nursing.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (NICE) Safe staffing for nursing in adult inpatient wards in acute hospitals. 2014 Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sg1.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Safe midwifery staffing for maternity settings. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng4.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE releases safe staffing evidence reviews. News brief. 2016 Jan 18; Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/news/feature/nice-releases-safe-staffing-evidence-reviews.

- National League for Nursing. Biennial survey of schools of nursing, academic year 2015–2016. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.nln.org/newsroom/nursing-education-statistics/biennial-survey-of-schools-of-nursing-academic-year-2015-2016.

- Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Mattke S, Stewart M, Zelevinsky K. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(22):1715–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Pankratz VS, Leibson CL, Stevens SR, Harris M. Nurse staffing and inpatient hospital mortality. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(11):1037–1045. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Digital. NHS workforce statistics, September 2017 national and HEE tables. 2017 Sep; Retrieved from https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB30165.

- NHS England. Integrated care pioneers: One year on. 2015a Feb; Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/integrtd-care-pionrs-1-yr-on.pdf.

- NHS England. A new strategy and vision for nursing, midwifery and care staff. 2015b Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/nursingvision/

- NHS Improvement. An improvement resource for learning disability services. 2016 Dec 21; Retrieved from https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/safe-staffingimprovement-resources-learning-disability-services/

- NHS Improvement. Safe, sustainable and productive staffing: An improvement resource for the district nursing service. 2017a Mar 15; Retrieved from https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/safe-staffing-district-nursing-services/

- NHS Improvement. Safe, sustainable and productive staffing: An improvement resource for mental health. 2017b Mar 15; Retrieved from https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/safe-staffing-mental-health-services/

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards for preregistration nursing education. 2010 Retrieved from https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/additional-standards/standards-for-pre-registration-nursing-education/

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Annual report and accounts 2016–2017 and strategic plan 2017–2018. 2017 Retrieved from https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/annual_reports_and_accounts/annual-report-and-accounts-2016-2017.pdf.

- Office of Management & Budget. Department of Health and Human Services. America first: A budget blueprint to make America great again. 2017 Retrieved from White House website: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget.

- Oliver D. Nurse staffing levels are still not safe. BMJ. 2016;353:i2665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Remuneration of nurses. Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/social-issuesmigration-health/health-at-a-glance-2015_health_glance-2015-en#page99.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 et seq. (2010).

- Prime Minister’s Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England. Front line care: The future of nursing and midwifery in England. Report of the Prime Minister’s Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England 2010. 2010 Retrieved from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100331110400/http:/cnm.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/front_line_care.pdf.

- Public Health Service Act of 1944, 42 U.S.C. § 296, 297. (2010).

- Rafferty AM, Clarke SP, Coles J, Ball J, James P, McKee M, Aiken LH. Outcomes of variation in hospital nurse staffing in English hospitals: Cross-sectional analysis of survey data and discharge records. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2007;44(2):175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts TC, Fraher EP. Reconfiguring health workforce policy so that education, training, and actual delivery of care are closely connected. Health Affairs. 2013;32(11):1874–1880. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Nursing. Safe staffing levels—A national imperative: The UK nursing labour market review 2013. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/541224/004504.pdf.

- Royal College of Nursing. An uncertain future. The UK nursing labour market review 2014. 2014 Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/597713/004_740.pdf.

- Royal College of Nursing. A workforce in crisis? The UK nursing labour market review 2015. 2015a Retrieved from https://www2.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/649922/RCN_Labour_Market_2015.pdf.

- Royal College of Nursing. Student bursaries, funding, and finance in England. 2015b Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk/about-us/policy-briefings/pol-1115.

- Royal College of Nursing. Unheeded warnings: Health care in crisis. The UK nursing labour market review 2016. 2016a Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-005779.

- Royal College of Nursing. Royal College of Nursing response to Health Education England’s consultation: Building capacity to care and capability to treat –a new team member for health and social care. 2016b Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-005567.

- Royal College of Nursing. Response to NHS Improvement’s draft sustainable safe staffing improvement resource—learning disabilities. 2017a Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk/about-us/policy-briefings/conr-82b16.

- Royal College of Nursing. Response to NHS Improvement’s draft sustainable safe staffing improvement resource in mental health. 2017b Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk/about-us/policy-briefings/conr-2117.

- Royal College of Nursing. Response to NHS Improvement’s draft sustainable safe staffing improvement resource on safe caseloads in district nursing services. 2017c Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk/about-us/policybriefings/conr-2017.

- Royal College of Nursing London. RCN London Safe Staffing Report 2015. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk/london/about/publications/safe-staffing-report-2015.

- S6768. Assemb. Reg. Sess 2017–2018. N.Y: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spetz J. Projection tool: Background and sources. 2017 Retrieved from Campaign for Action website: https://campaignforaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/BSN-map-How-To-Read-2016-11-16-1.pdf.

- Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, P.L. 115–97 § 11081 et seq. (2017).

- Title VIII Nursing Workforce Reauthorization Act of 2017, H.R. 959, 115th Cong. (2017).

- Title VIII Nursing Workforce Reauthorization Act of 2017, S.1109, 115th Cong. (2017).

- Universities and Colleges Admissions Service. Summary statistics of nursing applicants. 2017 Retrieved from https://www.ucas.com/file/115961/download?token=n9lk8cCN.

- U.S. Department of Education. The database of accredited postsecondary institutions and programs: Agency list. 2017 Retrieved from https://ope.ed.gov/accreditation/agencies.aspx.

- Yakusheva O, Lindrooth R, Weiss M. Economic evaluation of the 80% baccalaureate nurse workforce recommendation: A patient-level analysis. Medical Care. 2014;52(10):864–869. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]