Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine the occurrence of latent tuberculosis infections (LTBI) and active TB in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treated with biologics. We also examined the effects of immunosuppressive drugs on indeterminate interferon-gamma release assays (IGRA) in LTBI screening.

Design

Retrospective study of patients treated with biologics between March 2007 and November 2015.

Setting

St Mark’s Hospital, North West London, UK.

Patients

732 patients with IBD who were screened for LTBI using either tuberculin skin test or IGRA before starting a biologic treatment.

Methods

Retrospective case note review of all patients with IBD who were screened for LTBI prior to initiating biologics. Patients who developed active TB were identified from the London TB register.

Results

Of 732 patients with IBD, 31 (4.2%) were diagnosed with and treated for LTBI with no significant side effects. Six of 596 patients (1.0%) who received biologic treatment developed active TB. There was a higher proportion of indeterminate IGRA in the immunosuppressive medication group compared with the non-immunosuppressive group (33% (59/181) compared with 9% (6/66), p<0.001). The combination of steroids and thiopurines had the highest proportion of indeterminate IGRA (64%, 16/25). High and low doses of steroids were equally likely to result in an indeterminate IGRA result (67% (8/12) and 57% (4/7), respectively).

Conclusions

This study highlights the challenges of LTBI screening prior to commencing biologic therapy and demonstrates the risk of TB in patients who have been screened and who are receiving prolonged and continuing doses of antitumour necrosis factor.

Keywords: ibd, crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, infliximab

Introduction

Biologic treatments, such as antitumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapies, have led to significant improvements in outcomes for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but are associated with an increased risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection.1 Individual risk of developing M. tuberculosis infection is influenced by the type of biologic drug, concomitant immunosuppressive therapies and other epidemiological factors.2 Identifying and treating latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) and active TB in the context of biologic therapy is challenging, because the altered immune response gives rise to atypical presentation such as extrapulmonary and disseminated mycobacterial disease.1

The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) recommend that, before commencing biologic treatment, screening for LTBI should be undertaken using a combination of history, chest X-ray (CXR) and tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) according to local prevalence of TB, national guidance and BCG status.3 TST and IGRA have limitations in diagnosing LTBI, including increased false negatives among immunosuppressed patients.4

Although specificity for diagnosing LTBI using IGRAs is reported as 95%, there are issues around reproducibility and indeterminacy of test results.5 Indeterminate results can occur in 2% of the healthy population,5 and in up to 12% of immunocompromised or immunosuppressed patients.6 While it is known that concomitant treatment with steroids can affect IGRA test results, less is known about the effects of other immunosuppressive medications. Indeterminate IGRA results in the context of possible LTBI may delay the initiation of biologic treatment because of the need for repeat testing and consultation with TB services.

The primary aim of this study was to determine rates of LTBI in our IBD cohort treated with biologics by two screening methods—TST (to July 2013) and IGRA (from July 2013). Secondary aims were to determine the effects of different immunosuppressive drugs on the frequency of indeterminate IGRA test results and to review cases of active TB which developed during biologic treatment.

Methods

St Mark’s Hospital is a national and international referral centre for patients with IBD in North West London, UK. It is part of London North West Healthcare NHS Trust, which serves an ethnically diverse population from the London boroughs of Brent, Harrow and Ealing. Local TB rates are up to 82.9 per 100 000, compared with a London wide average of 13.5 per 100 000.7

We conducted a retrospective case note review of all patients with IBD who were screened prior to initiating biologics between March 2007 and November 2015. Patients were identified from the high-cost funding database held at St Mark’s Hospital pharmacy. Data were collected from the hospital electronic patient information system, the radiology picture archiving and communication system and the integrated clinical environment test results system and by reviewing available hand-written patient notes.

LTBI screening information was obtained from risk assessment templates, X-ray reports and TST or IGRA test results. Of note, in July 2013, IGRA testing replaced TST in the LTBI screening algorithm. For patients diagnosed with LTBI, the nature of their IBD treatment and LTBI treatment (either isoniazid alone for 6 months or combined rifampicin and isoniazid for 3 months) was recorded, including any adverse events. Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) was defined as an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) rise of five times the upper limit of normal (ULN) without symptoms or 3–5 times the ULN with symptoms. Patients who developed active TB were identified from the London TB register. The Χ2 test was used to compare categorical data, including the effect of immunosuppressive medications and the effect of steroid dose on the proportion of indeterminate IGRA test results.

Results

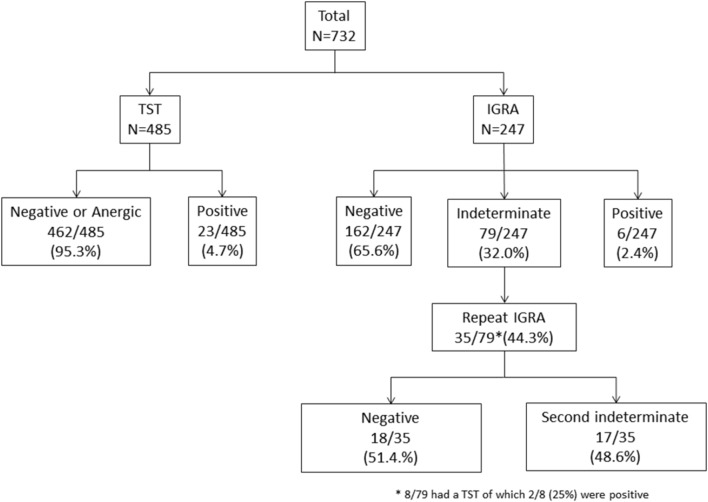

During the study period, 732 patients with IBD who were considered for starting a biologic treatment were screened for LTBI with either a TST or IGRA. Of these 732 patients, 485 (66.3%) were screened with a TST of whom 23/485 (4.7%) were positive, and 247 (33.7%) were screened with an IGRA of whom 6/247 (2.4%) were positive (figure 1). The median age was 39 (IQR 21–50) years, 51% were male, 76% had Crohn’s disease (CD), 24% had ulcerative colitis (UC) and 0.4% had IBD unclassified (table 1).

Figure 1.

Tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) results of patients included in this study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (n=732)

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 39 (21–50) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 373 (50.9%) |

| Crohn’s disease, n (%) | 556 (76.0%) |

| Ulcerative colitis, n (%) | 173 (23.6%) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease unclassified, n (%) | 3 (0.4%) |

| Latent tuberculosis infection, n (%) | 31 (4.2%) |

| Active tuberculosis, n (%) | 6 (1) |

| Biologic treatment, n (%) | 596 (81.4%) |

Latent TB infection

Of 732 patients, 31 patients (4.2%) were diagnosed and treated for LTBI during the study period; 23 (74.2%) TST positive, six (19.4%) IGRA positive and two (6.5%) TST positive after an indeterminate IGRA (figure 1). Of the 31 patients with LTBI, 19 (61.3%) received isoniazid alone for 6 months and 12 (38.7%) had combined rifampicin and isoniazid for 3 months; 22/31 (71.0%) patients went on to have anti-TNF treatment with a median time to starting treatment of 86 (IQR 56–166) days. Nine patients did not receive biologic treatment at St Mark’s hospital for various reasons, including surgery precluding the need for biologics, disease improvement or receiving biologic treatment elsewhere. One patient treated for LTBI reported dizziness which was not severe enough to warrant stopping treatment. No serious adverse events occurred and there were no occurrences of DILI.

IGRA-based LTBI screening

IGRA replaced TST from July 2013, and 247 patients were screened for TB with an IGRA test. The median age was 34 (IQR 25–46) years, 54% (133) were male, 70% (173) had CD and 30% (74) had UC. Of the 247 patients screened with IGRA, 208 patients (84.2%) received biologic treatment at St Mark’s Hospital. Of 247 patients, 39 patients (16%) were not treated with their biologic treatment at the time of study for reasons which included LTBI treatment, surgery or disease improvement. Of 208 patients, 158 patients (76%) subsequently received infliximab, 38 (18%) received adalimumab, 11 (5%) vedolizumab and one (0.5%) patient received golimumab.

Twenty-nine IGRA-screened patients were referred to the Infectious Diseases team for a specialist TB opinion from July 2013 to November 2015—six with a positive IGRA, 17 an indeterminate IGRA and six with an abnormality on their CXR and a high epidemiological risk for TB despite a negative IGRA. Eight patients were treated for LTBI and one for active TB.

Effect of immunosuppressive medications on IGRA

Of 247 patients, 181 patients (73%) were receiving at least one immunosuppressive medication at the time of IGRA-based screening. Of 181 patients in the immunosuppressive medication group, 121 (66.8%) patients were on thiopurines, 19 (10.4%) on corticosteroids, 25 (13.8%) on corticosteroids and thiopurines, nine (4.9%) on methotrexate and seven (3.9%) other on immunosuppressive medications.

Of the 66 patients who were not on any immunosuppressive medications, two (3.0%) had a positive result, 58 (87.9%) had a negative result and six (9.0%) had an indeterminate IGRA result. Repeat testing did not change any of the indeterminate results (to positive or negative) (table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of different immunosuppressive medications on IGRA results

| Immunosuppressive medication | Number of patients | IGRA test result, n (%) | P values* | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Indeterminate | |||||

| First test (%) | First test (%) | After repeat test (%) | First test (%) | After repeat test (%) | |||

| No immunosuppressive | 66 | 2 (3.0) | 58 (87.9) | 58 (87.9) | 6 (9.0) | 6 (9.0) | |

| Any immunosuppressive | 181 | 4 (2.2) | 106 (58.6) | 119 (65.7) | 72 (39.8) | 59 (32.6) | <0.001 |

| Thiopurines | 121 | 2 (1.7) | 84 (69.4) | 92 (76.0) | 36 (29.8) | 28 (23.1) | 0.02 |

| Corticosteroids | 19 | 1 (5.3) | 6 (31.6) | 10 (52.6) | 11 (57.9) | 8 (42.1) | 0.001 |

| Thiopurines and corticosteroids | 25 | 1 (4.0) | 8 (32.0) | 8 (32.0) | 16 (64.0) | 16 (64.0) | <0.001 |

| Methotrexate | 9 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | 0.02 |

| Other* | 7 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 0.04 |

*Χ2 test (Fisher’s exact if cell frequency <5) comparing proportion of indeterminate IGRA test results in medication versus non-medication groups. ‘Other’ included tacrolimus and mycophenolate.

IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay.

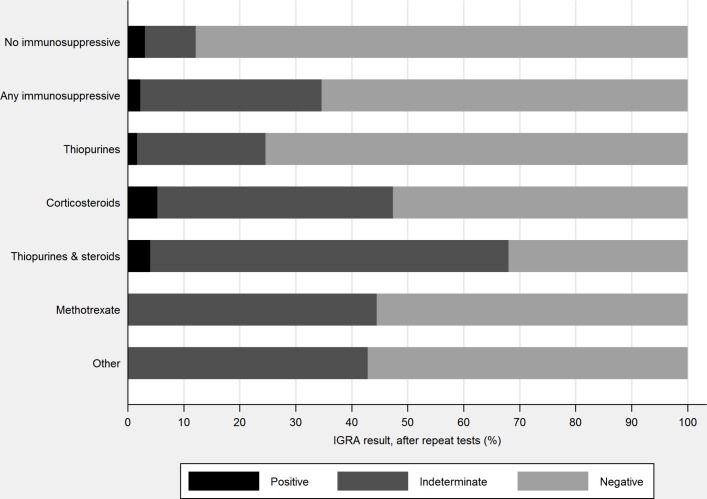

Among the 181 patients receiving immunosuppressive medication, four (2.2%) had a positive IGRA test result, 106 (58.6%) a negative result and 72 (39.8%) an indeterminate result. After repeat testing of patients with an indeterminate result, a total of 59/181 (32.6%) had an indeterminate result, compared with 9% (6/66) of patients not on immunosuppressive medication (p<0.001) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of immunosuppressive medications on interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) results.

Patients in each immunosuppressive medication group were more likely to have an indeterminate IGRA result, compared with patients not on any immunosuppressive medication: thiopurines 23.1% (28/121, p=0.02), corticosteroids 42.1% (8/19, p=0.001), thiopurines and corticosteroids 64.0% (16/25, p<0.001), methotrexate 44.4% (4/9, p=0.02) and other four (3/7, p=0.04) (figure 2).

Effect of steroid dose on IGRA

Patients on high-dose medication (prednisolone >20 mg or intravenous hydrocortisone) had a higher proportion of indeterminate IGRA test results—66.6% (8/12) before repeats, 58.3% (7/12) after repeats—compared with patients on low doses (prednisolone <20 mg or budesonide)—57.1% (4/7) before repeats, 28.6% (2/7) after repeats—but this apparent difference was not supported by statistical evidence (Fisher’s exact test, before repeat p=1.00, after repeat p=0.35).

Patients with active TB

Five hundred and ninety six patients received biologic treatment at St Mark’s Hospital during the study period. Six out of 596 (1.0%) developed active TB following the biologic treatment, of whom five had CD and one had UC. The median age was 31 (IQR 26–38) years. Five patients were Caucasian, one was born in the UK but of Pakistani origin; all were HIV negative; three had prior vaccinations for TB, one did not and the vaccination status of two was unknown. Five patients had negative TSTs prior to starting biologics, and one patient had an indeterminate IGRA. All six patients were immunosuppressed at the time of testing and had chest imaging prior to biologic treatment. None received LTBI treatment prior to biologic treatment. All were deemed to be at low epidemiological risk of TB.

All patients with active TB had received adalimumab and infliximab anti-TNF therapy (three patients receiving adalimumab had previously been treated with infliximab) (table 3). The median time from initiation of the most recent anti-TNF therapy to TB diagnosis was 15 (IQR 13–31) months. One patient receiving weekly adalimumab was pregnant and therefore dose frequency was reduced to alternate weeks. This patient underwent a caesarean section at 32 weeks’ gestation and M. tuberculosis was later isolated from ascitic fluid samples. The patient returned to theatres day 3 post-op for further surgery, which demonstrated a caecal mass with a contained perforation; histology was in keeping with possible CD and further TB cultures were negative.

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients with IBD with active TB

| Age (sex) | Disease | Ethnicity | Risk factors for TB | Site of TB | Evidence for TB | Screening test: result (immunosuppressed at time of test) |

Anti-TNF therapy (time since initiation of therapy) (previous anti-TNF duration) |

| 49 (F) | CD | Caucasian | None known | Miliary | TST positive. Multiple interstitial lung nodules, ground glass changes and enlarged porta hepatitis nodes on CT scan. Liver biopsy: granulomatous inflammation. | TST: negative (yes) | Adalimumab (13 months) (Infliximab, one dose, allergic reaction on second dose) |

| 33 (M) | CD | Caucasian | None known | Pulmonary+ pericardial |

TST positive. Pericardial fluid and induced sputum PCR and culture positive for MTB. | TST: negative (yes) | Infliximab (41 months) |

| 40 (F) | CD | Caucasian | Worked at a hospital | Miliary | QFT-G positive. Induced sputum PCR positive for MTB. Radiological features of miliary TB in lungs on CT scan. | TST: negative (yes) | Infliximab (35 months) |

| 24 (M) | UC | Pakistani (UK born) | Ethnic origin, last trip to Pakistan 10 years prior | Pulmonary with pleural effusion | Induced sputum PCR and culture positive for MTB | IGRA: indeterminate (yes) | Infliximab (4 months) |

| 28 (F) | CD | Caucasian | None known | Abdominal | Ascitic fluid caesarean section culture positive for MTB. | TST: negative (yes) | Adalimumab (13 months) (Infliximab, two doses, allergic reaction on third dose) |

| 25 (M) | CD | Caucasian | None known | Abdominal lymph node | Lymph node biopsy: granulomatous inflammation. Extensive mesenteric lymph nodes on CT abdomen. | TST: negative (yes) | Adalimumab (17 months including 5 month break for surgery, restarted 3 months prior to diagnosis) (Infliximab, 12 months, switched due to loss of response) |

CD, Crohn’s disease; IGRA, interferon-gamma release assays; MTB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; QFT-G, QuantiFERON-TB Gold; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Three patients had culture-confirmed TB, one was PCR TB complex positive but culture negative and two patients were treated for active TB on the basis of consistent clinical and radiological features. All isolated cultures were fully sensitive to the first-line therapies. Two patients presented with miliary TB, two had abdominal TB disease, one had pleuro-pulmonary TB and one patient presented with both pulmonary and pericardial TB. Treatment duration was for 6–12 months depending on the site and severity of disease; five patients completed treatment and one remained on treatment beyond the study period.

Discussion

The overall rate of presumed LTBI in this population receiving biologics for IBD was 4%. Time to start biologics after a diagnosis of LTBI at a median of 86 (IQR 56–166) days represents a time lag with potential consequences for patients with IBD. ECCO guidelines suggest delaying anti-TNF treatment for at least 3 weeks after initiating LTBI chemoprophylaxis; this can be shortened if there is clinical urgency for anti-TNF therapy.3 The timing of starting anti-TNF after initiation of LTBI needs to be individualised according to the risk of developing active TB, the risk of hepatotoxicity with LTBI treatment, severity of underlying IBD disease and patient choice.

The incidence of active TB in this cohort was 1%, which was significantly higher than in the average UK (12.0/100 000) and London (26.2/100 000) general population,8 but lower than in anti-TNF treated patient cohorts in South Korea (2.9%)9 and Turkey (4.7%).10 Our rate for presumed LTBI (4%) was also lower than in a Korean cohort of anti-TNF treated patients.11 These differences probably reflect our strategy of active identification of LTBI through screening, and different background TB incidence rates. The high incidence of extrapulmonary TB in our cohort was consistent with the other studies.12

Almost one-third of patients with IBD in our study had an initial indeterminate IGRA test result, of whom half had a repeat indeterminate result. An indeterminate IGRA result can indicate failure of the positive control, which measures IFN-γ response against phytohaemagglutinin,6 because of a reduction in the number and function of T lymphocytes or failure of IFN-γ production.13 Immunosuppressors, which affect this cell-mediated response, can therefore result in a higher proportion of indeterminate tests. The proportion of indeterminate IGRAs in patients on immunosuppressives was much higher in our study (32%) than in a Swiss IBD cohort (3%), even though a similar proportion of patients in each cohort were on immunosuppressive medication (UK cohort 73%, Swiss cohort 81%).14 An explanation for this difference in indeterminate results would require more detailed characterisation and comparison of the two cohorts, perhaps including data to characterise IBD activity, which has been shown to be strongly associated with indeterminate IGRAs in paediatric patients with IBD.15

The high proportion of indeterminate IGRAs in our patient population suggests that risk stratification, including factors such as country of origin and local TB prevalence, may be important in the screening of TB prior to biologic therapy in immunosuppressed patients.16 However, even with risk stratification some patients may be missed, as demonstrated by the six cases in our study who developed active TB, all of whom were deemed to be at low risk of LTBI. This reinforces the message that there is no perfect system to identify all patients with LTBI and that vigilance for active TB in patients on biologics is required.

We included patients with IBD who were screened with TST before the introduction of IGRAs to obtain an overall estimate of the proportion of patients screened who had LTBI. TST can be falsely negative in immunosuppressed patients17; therefore, we may have underestimated the overall prevalence of LTBI. In practice, patients who come from a high TB prevalence country are considered for LTBI prophylaxis regardless of their TST or IGRA result. Whereas TST or IGRA could be used for LTBI screening in patients from low TB prevalence areas without BCG vaccination,18 early screening with IGRA should be considered in immunosuppressed and BCG-vaccinated patients.14

Patients on a combination of thiopurines and corticosteroids had the highest proportion of indeterminate IGRA results, although all immunosuppressive medications were associated with a higher rate of indeterminate IGRAs. This has implications for LTBI screening in patients with IBD, given the delays associated with indeterminate results. To avoid these delays, LTBI screening could be considered prior to commencement of immunosuppressive medication in patients with IBD with severe ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, or a patient’s baseline risk of LTBI could take precedence over IGRA-based screening. This is similar to the approach recommended in British Thoracic Society guidelines,19 which were written when TST was the most commonly available LTBI screening test. Future guidelines need to take into account indeterminate IGRA results and give weight to epidemiological risk. However, given that all active cases of TB in our study were considered to be of low epidemiological risk, guidance regarding rescreening strategies might also be needed. For example, in treating patients with IBD who have been screened and who are receiving prolonged and continuing doses of anti-TNF, close liaison with a TB service is advised,20 and even negative IGRA test results should not exclude the possibility of LTBI.6 Any rescreening strategy needs to take into account conversion of TB tests and dynamic IGRA responses during anti TNF-treatment21 and should not exclude patients previously treated with biologics.22 Taken together, such a strategy has the potential to reduce, if not eliminate, the risk of patients developing active TB.

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this topic

Biologic treatment for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) carries an increased risk of tuberculosis (TB).

Concomitant treatment with steroids can affect interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) results.

What this study adds

This is the first large retrospective study in the UK of the incidence of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) and active TB in patients with IBD treated with biologics.

We have identified the relationship between an indeterminate IGRA and immunosuppressive drugs used for IBD treatment.

We have highlighted the importance of vigilance for active TB in patients treated with biologics.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

This study may support new strategies in screening for LTBI in patients on immunosuppressive drugs for IBD.

This study demonstrates the need for vigilance for the development of active TB in patients with IBD on biologics, even if deemed of low epidemiological risk.

Footnotes

Contributors: AAT, LJ and ALH planned and designed the study. AAT, AA, SB, PW, LO and KGB collected and prepared the data. AAT, SMC and AA conducted the analyses. All authors were involved in the interpretation of results, drafting and revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data on which this study was based can be made available by the corresponding author to bona fide researchers subject to appropriate ethical approvals.

References

- 1. Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, et al. . Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1098–104. 10.1056/NEJMoa011110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Solovic I, Sester M, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. . Series ‘update on tuberculosis’ edited by C. Lange, M. Raviglione, W.W. Yew and G.B. Migliori number 2 in this series: the risk of tuberculosis related to tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapies: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J 2010;36:1185–206. 10.1183/09031936.00028510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, et al. . Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:443–68. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Debeuckelaere C, De Munter P, Van Bleyenbergh P, et al. . Tuberculosis infection following anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease, despite negative screening. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:550–7. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wong SH, Gao Q, Tsoi KK, et al. . Effect of immunosuppressive therapy on interferon γ release assay for latent tuberculosis screening in patients with autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2016;71:64–72. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lalvani A, Millington KA. Screening for tuberculosis infection prior to initiation of anti-TNF therapy. Autoimmun Rev 2008;8:147–52. 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brent Council. Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA): tuberculosis. 2015. https://www.brent.gov.uk/jsna

- 8. Public Health England (PHE). Tuberculosis in England 2016 report (presenting data to end of 2015). 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tuberculosis-in-england-annual-report

- 9. Byun JM, Lee CK, Rhee SY, et al. . The risk of tuberculosis in Korean patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving tumor necrosis factor-α blockers. J Korean Med Sci 2015;30:173 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.2.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Çekiç C, Aslan F, Vatansever S, et al. . Latent tuberculosis screening tests and active tuberculosis infection rates in Turkish inflammatory bowel disease patients under anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Ann Gastroenterol 2015;28:241–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim ES, Song GA, Cho KB, et al. . Significant risk and associated factors of active tuberculosis infection in Korean patients with inflammatory bowel disease using anti-TNF agents. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:3308–16. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abreu C, Magro F, Santos-Antunes J, et al. . Tuberculosis in anti-TNF-α treated patients remains a problem in countries with an intermediate incidence: analysis of 25 patients matched with a control population. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:e486–e492. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miranda C, Yen-Lieberman B, Terpeluk P, et al. . Reducing the rates of indeterminate results of the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test during routine preemployment screening for latent tuberculosis infection among healthcare personnel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:296–8. 10.1086/595732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schoepfer AM, Flogerzi B, Fallegger S, et al. . Comparison of interferon-gamma release assay versus tuberculin skin test for tuberculosis screening in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2799–806. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hradsky O, Ohem J, Zarubova K, et al. . Disease activity is an important factor for indeterminate interferon-γ release assay results in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;58:320–4. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nasr I, Goel RM, Ward MG, et al. . Su1101 indeterminate and inconclusive results are common when using interferon gamma release assay as screening for TB in patients with IBD. Gastroenterology 2014;146:S-374 10.1016/S0016-5085(14)61350-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tavast E, Tuuminen T, Pakkanen SH, et al. . Immunosuppression adversely affects TST but not IGRAs in patients with psoriasis or inflammatory musculoskeletal diseases. Int J Rheumatol 2012;2012:1–8. 10.1155/2012/381929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andrisani G, Armuzzi A, Papa A, et al. . Comparison of Quantiferon-TB Gold versus tuberculin skin test for tuberculosis screening in inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2013;22:21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ormerod LP, Milburn HJ, Gillespie S, et al. . BTS recommendations for assessing risk and for managing Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and disease in patients due to start anti-TNF-alpha treatment. Thorax 2005;60:800–5. 10.1136/thx.2005.046797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jung YJ, Woo HI, Jeon K, et al. . The significance of sensitive interferon gamma release assays for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in patients receiving tumor necrosis factor-α antagonist therapy. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141033 10.1371/journal.pone.0141033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Drago L, Nicola L, Signori V, et al. . Dynamic QuantiFERON response in psoriasis patients taking long-term biologic therapy. Dermatol Ther 2013;3:73–81. 10.1007/s13555-013-0020-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vaughn BP, Doherty GA, Gautam S, et al. . Screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis B prior to the initiation of anti-tumor necrosis therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:1057–63. 10.1002/ibd.21824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]