Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Statin medications, most commonly prescribed to reduce lipid levels and prevent cardiovascular disease, may be associated with longer survival times of patients with cancer. However, the association of statins with outcomes of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma is not clear.

METHODS

We analyzed the association of statin use before a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer with survival times of 648 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study who were diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma from 2000 through 2013. We estimated hazard ratios (HRs) for overall mortality using Cox proportional hazards models with adjustment for potential confounders. We assessed the temporal association between pre-diagnosis statin use and cancer survival by 2-year lag periods to account for a possible latency period between statin use and cancer survival.

RESULTS

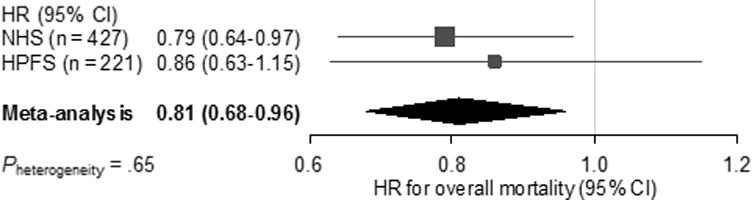

Regular statin use before diagnosis of pancreatic cancer was associated with modestly prolonged survival compared to non-regular use (adjusted HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69–0.97; P = .02). A 1-month longer median survival was observed in regular statin users compared to non-regular users. Regular statin use within the 2 years prior to cancer diagnosis was most strongly associated with longer survival. We observed no statistically significant effect modification by smoking status, body mass index, diabetes, or cancer stage (all Pinteraction > .53). Regular statin use before diagnosis was similarly associated with survival in the Nurses’ Health Study (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.64–0.97) and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.63–1.15).

CONCLUSIONS

Regular statin use before diagnosis of pancreatic cancer was associated with modest increases in survival times in 2 large prospective cohort studies.

Keywords: Epidemiology, HPFS, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors, Neoplasm, NHS

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a top cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide and is the third leading cause in the United States (U.S.).1 This high mortality rate is largely related to the diagnosis of patients at advanced stages when the disease is unresectable and thus incurable.2 Despite development of new combination chemotherapy programs,3,4 most patients with advanced pancreatic cancer survive for less than 12 months.1 Therefore, identifying new therapies that can improve survival among patients with pancreatic cancer is urgently needed.

Statins are 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors primarily used for their lipid-lowering properties, and the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. More recently, this class of medication has been studied for chemopreventative and chemotherapeutic properties given their complex effects on inflammation, angiogenesis, and cellular proliferation and apoptosis.5–8 While a meta-analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials failed to show an effect of statin use on overall cancer incidence or mortality,9 observational studies support that statins may decrease the risk of certain cancer types as well as cancer-related mortality.7,8,10,11

Among patients with pancreatic cancer, retrospective cohort studies have suggested a survival benefit associated with regular statin use both in resectable and unresectable pancreatic cancer;12–16 however, these prior studies were limited by modest sample sizes and/or retrospective study design. Thus, to examine the association between statin use and survival among patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, we conducted a prospective study within 2 large U.S. cohorts that ascertained detailed information on pre-diagnosis statin use over an extended period of follow-up. Prospectively-collected, nationwide data allowed us to examine pre-diagnosis statin use and survival in a representative sample of pancreatic cancer patients in the U.S., to explore the temporal prognostic association of pre-diagnosis statin use without substantial recall bias, and to adjust for a comprehensive set of lifestyle factors.

Methods

Study Population

We collected data from 2 ongoing prospective U.S. cohort studies, the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS). The NHS enrolled 121,700 female nurses aged 30–55 years in 1976.17 The HPFS enrolled 51,529 male health professionals aged 40–75 years in 1986.18 Participants from both cohorts complete mailed questionnaires that collect information on demographics, lifestyle habits, medical history, medication usage, and health outcomes, including cancer diagnoses.

We included 648 patients diagnosed with incident pancreatic cancer between 2000 and 2013 and followed them through May 31, 2014 (NHS) or January 31, 2014 (HPFS). Follow-up questionnaires were completed every 2 years with follow-up rates exceeding 90%.19 We excluded patients with non-adenocarcinoma histology or history of cancer at baseline (except non-melanoma skin cancer), and those without available data on pre-diagnosis statin use and survival.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in each cohort, and the studies were approved by the Human Research Committee at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA).

Ascertainment of Statin Use

Information on statin use was first assessed by the 2000 questionnaire and updated biennially. In 2000, participants were asked whether they used statins regularly (yes/no) as well as the duration of statin use (0–2, 3–5, or ≥ 6 years in NHS; and 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, or ≥ 10 years in HPFS). Duration of statin use was calculated from participant responses from the 2000 questionnaire combined with subsequent current use responses on follow-up questionnaires. Details on statin use ascertainment in these cohorts have been previously described.20,21 The primary exposure for the current study was pre-diagnosis statin use as reported on the questionnaire prior to pancreatic cancer diagnosis.

Ascertainment of Covariates

Data on covariates were collected at baseline (1980 NHS; 1986 HPFS) and on follow-up questionnaires including age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), and diabetes mellitus (DM) status. Information on use of aspirin, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and angiotensin system inhibitors was also collected (detailed in Supplementary Methods).22–24

Ascertainment of Pancreatic Cancer Cases

Patients with pancreatic cancer were identified by self-report, next-of-kin, or review of the computerized National Death Index. Physicians blinded to exposure status confirmed the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer by review of medical records, death certificates, or cancer registry data. Deaths were ascertained from next of kin, U.S. postal service, or the National Death Index; this method has been shown to capture >98% of deaths.25 Date of pancreatic cancer diagnosis and stage at diagnosis were determined through physician review of medical records. Cancer stage was classified as: localized (amenable to surgical resection); locally advanced (unresectable due to extrapancreatic extension but no distant metastases); or metastatic.

Statistical Analysis

We examined the association between pre-diagnosis statin use (regular vs. non-regular use) and overall survival among patients with pancreatic cancer. Overall survival time was calculated as time from pancreatic cancer diagnosis to death or last follow-up, whichever came first. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for overall mortality by pre-diagnosis statin use. The multivariable Cox regression models were adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), cohort (sex), race/ethnicity (white, black, other, or unknown), year of cancer diagnosis (2000–2005 or 2006–2013), smoking status (never, past, current, or unknown), BMI (continuous), and DM status (no, recent-onset [≤ 4 years prior to cancer diagnosis], or long-standing [> 4 years prior to cancer diagnosis]). Further adjustments were made for cancer stage at diagnosis (localized, locally advanced, metastatic, or unknown), a covariate not included in the initial model as it may be part of the causal pathway between pre-diagnosis statin use and pancreatic cancer survival. Given that medications frequently prescribed with statins may also have anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer,26–28 we further examined pre-diagnosis use (regular vs. non-regular use) of aspirin, other NSAIDs, and angiotensin system inhibitors as confounders in our analyses of statin use and patient survival.

The assumption of proportionality of hazards was satisfied by evaluating a time-dependent covariate, which was the cross-product of pre-diagnosis statin use and survival time (P = .48). We estimated median overall survival time and survival curves adjusted for covariates by using direct adjusted survival estimation.29,30 This method uses the Cox regression model to estimate survival probabilities at each time-point for each individual and averages them to obtain an overall survival estimate. We examined the heterogeneity in the association of pre-diagnosis statin use with pancreatic cancer survival between the cohorts using Cochran’s Q statistic.31 We computed a pooled HR for overall mortality by pre-diagnosis statin use using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model.32 As exploratory analyses, we assessed reported statin use by 2-year time intervals prior to pancreatic cancer diagnosis and examined whether the association of pre-diagnosis statin use with pancreatic cancer survival differed by lag time between statin use and cancer diagnosis. We also performed stratified analyses by year of diagnosis, smoking status, BMI, DM status, and cancer stage at diagnosis. We assessed statistical interaction by entering main effect terms and the cross-product of pre-diagnosis statin use and a stratification variable into the model and evaluating likelihood ratio tests.

Two-sided P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of 648 patients diagnosed with incident pancreatic adenocarcinoma over the follow-up period are summarized by cohort and pre-diagnosis statin use in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1, respectively. In the combined population, 247 patients (38.1%) were regular statin users before diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Median adjusted survival time by stage was 18, 9, and 3 months for localized, locally advanced, and metastatic disease, respectively. At the end of follow-up, 633 pancreatic cancer cases (97.7% of combined cohort) were deceased.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Pancreatic Cancer by Cohort.

| NHS | HPFS | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic a | (n = 427) | (n = 221) | (n = 648) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 75.2 ± 6.9 | 77.1 ± 8.3 | 75.9 ± 7.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 413 (96.8) | 204 (92.3) | 617 (95.2) |

| Black | 7 (1.6) | 2 (0.9) | 9 (1.4) |

| Other | 7 (1.6) | 6 (2.7) | 13 (2.0) |

| Unknown | 0 | 9 (4.1) | 9 (1.4) |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2000–2005 | 180 (42.2) | 103 (46.6) | 283 (43.7) |

| 2006–2013 | 247 (57.8) | 118 (53.4) | 365 (56.3) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 180 (42.2) | 93 (42.1) | 273 (42.1) |

| Past | 207 (48.5) | 118 (53.3) | 325 (50.2) |

| Current | 39 (9.1) | 5 (2.3) | 44 (6.8) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 5 (2.3) | 6 (0.9) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.3 ± 5.5 | 25.4 ± 3.2 | 26.0 ± 4.8 |

| Diabetes mellitus status | |||

| No diabetes | 328 (76.8) | 173 (78.2) | 501 (77.3) |

| Recent-onset (≤ 4 years) | 24 (5.6) | 7 (3.2) | 31 (4.8) |

| Long-standing (> 4 years) | 75 (17.6) | 41 (18.6) | 116 (17.9) |

| Cancer stage | |||

| Localized | 53 (12.4) | 38 (17.2) | 91 (14.0) |

| Locally advanced | 27 (6.3) | 19 (8.6) | 46 (7.1) |

| Metastatic | 220 (51.6) | 108 (48.9) | 328 (50.7) |

| Unknown | 127 (29.7) | 56 (25.3) | 183 (28.2) |

| Regular statin use before diagnosis | |||

| No | 272 (63.7) | 129 (58.4) | 401 (61.9) |

| Yes | 155 (36.3) | 92 (41.6) | 247 (38.1) |

HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number of patients (%).

Compared with patients who did not regularly take statins before diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, regular statin use was associated with longer survival after adjustment for age, cohort (sex), race/ethnicity, year of diagnosis, smoking status, BMI, and DM status within the combined population (HR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69–0.97; P = .02; Table 2 and Figure 1). The absolute difference in survival was modest, with median adjusted survival times of 6 months for regular statin users compared to 5 months for non-regular statin users. In the multivariable model further adjusted for cancer stage, the association of regular statin use before diagnosis with longer survival was similarly observed (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70–0.99; P = .03; Table 2). When further adjusted for pre-diagnosis use of aspirin, other NSAIDs, and angiotensin system inhibitors in the Cox regression model, we observed a consistent association of pre-diagnosis statin use and survival among patients with pancreatic cancer (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70–0.99). In addition, we did not observe synergistic effects of statins and any of these medications (data not shown). Notably, patients who regularly used statins before diagnosis had greater likelihood of presenting with localized disease compared with non-users, but this did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Table 2). Figure 2 shows cohort-specific results for overall survival in pancreatic cancer cases by pre-diagnosis statin use. Although we did not observe statistically significant heterogeneity in the association of pre-diagnosis statin use with survival by cohort (P = .65), the association with survival was nominally stronger in NHS cases compared to HPFS cases.

Table 2.

Overall Mortality Among Patients With Pancreatic Cancer by Pre-diagnosis Statin Use.

| Pre-diagnosis statin use

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-regular use | Regular use | P value | |

| Person-months | 3,888 | 2,635 | |

| No. of cases | 401 | 247 | |

| No. of deaths | 393 | 240 | |

| Median survival, months | 5 | 6 | |

| Age-adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (referent) | 0.85 (0.73–1.00) | .06 |

| Multivariable HR (95% CI)a | 1 (referent) | 0.82 (0.69–0.97) | .02 |

| Multivariable HR (95% CI)b | 1 (referent) | 0.83 (0.70–0.99) | .03 |

HR, hazard ratio.

The Cox proportional hazards model was adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), cohort (sex), race/ethnicity (white, black, other, or unknown), year of diagnosis (2000–2005 or 2006–2013), smoking status (never, past, current, or unknown), body mass index (continuous), and diabetes status (no, recent-onset, or long-standing).

Further adjusted for cancer stage (localized, locally advanced, metastatic, or unknown).

Figure 1.

Overall survival curves of patients with pancreatic cancer by pre-diagnosis statin use. Survival probabilities were adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), cohort (sex), race/ethnicity (white, black, other, or unknown), year of diagnosis (2000–2005 or 2006–2013), smoking status (never, past, current, or unknown), body mass index (continuous), and diabetes status (no, recent-onset, or long-standing).

Figure 2.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of HRs for overall mortality among patients with pancreatic cancer, comparing regular statin users before diagnosis with non-regular users in the NHS and HPFS. Squares and horizontal lines indicate cohort-specific multivariable-adjusted HRs and 95% CIs, respectively. Area of the square reflects cohort-specific weight (inverse of the variance). Diamond indicates pooled multivariable-adjusted HR (center) and 95% CI (width). HRs were adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), cohort (sex), race/ethnicity (white, black, other, or unknown), year of diagnosis (2000–2005 or 2006–2013), smoking status (never, past, current, or unknown), body mass index (continuous), and diabetes status (no, recent-onset, or long-standing).

HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; HR, hazard ratio; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study.

To examine the temporal association of pre-diagnosis statin use with pancreatic cancer survival, we evaluated statin use reported in each 2-year time interval prior to cancer diagnosis and found that the prognostic association of regular statin use appeared to be strongest with use within 2 years of cancer diagnosis, as opposed to earlier time periods (Table 3).

Table 3.

Temporal Association of Statin Use and Overall Mortality Among Patients With Pancreatic Cancer.

| Pre-diagnosis statin use

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time interval between reported statin use and cancer diagnosis | No. of cases | Non-regular use | Regular use | P value |

| HR | HR (95% CI)a | |||

| 0–2 years | 559 | 1 (referent) | 0.84 (0.70–1.00) | .05 |

| 2–4 years | 563 | 1 (referent) | 0.87 (0.72–1.04) | .12 |

| 4–6 years | 555 | 1 (referent) | 0.84 (0.69–1.02) | .08 |

| 6–8 years | 565 | 1 (referent) | 0.82 (0.66–1.01) | .06 |

| 8–10 years | 527 | 1 (referent) | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | .52 |

| 10–12 years | 454 | 1 (referent) | 0.95 (0.73–1.23) | .67 |

HR, hazard ratio.

The Cox proportional hazards model was adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), cohort (sex), race/ethnicity (white, black, other, or unknown), year of diagnosis (2000–2005 or 2006–2013), smoking status (never, past, current, or unknown), body mass index (continuous), and diabetes status (no, recent-onset, or long-standing).

We observed no statistically significant effect modification for the prognostic association of pre-diagnosis statin use by year of diagnosis, smoking status, BMI, or DM status (Table 4). In addition, we did not observe a statistically significant interaction between pre-diagnosis statin use and cancer stage in relation to pancreatic cancer survival (Pinteraction = .54, Table 4 and Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 4.

Overall Mortality Among Patients With Pancreatic Cancer by Pre-diagnosis Statin Use Stratified by Covariates.

| Pre-diagnosis statin use

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of | No. of | Non-regular use | Regular use | ||

| Covariate | cases | deaths | HR | HR (95% CI)a | Pinteraction |

| Year of diagnosis | .64 | ||||

| 2000–2005 | 283 | 280 | 1 (referent) | 0.86 (0.66–1.11) | |

| 2006–2013 | 365 | 353 | 1 (referent) | 0.79 (0.64–0.98) | |

| Smoking status | .89 | ||||

| Never | 273 | 265 | 1 (referent) | 0.80 (0.62–1.04) | |

| Past | 325 | 319 | 1 (referent) | 0.86 (0.68–1.08) | |

| Current | 44 | 44 | 1 (referent) | 0.76 (0.41–1.39) | |

| Body mass index | .79 | ||||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 305 | 297 | 1 (referent) | 0.85 (0.66–1.10) | |

| ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 343 | 336 | 1 (referent) | 0.81 (0.65–1.01) | |

| Diabetes status | .98 | ||||

| No diabetes | 501 | 489 | 1 (referent) | 0.83 (0.68–1.00) | |

| Recent-onset (≤ 4 years) | 31 | 30 | 1 (referent) | 0.83 (0.41–1.71) | |

| Long-standing (> 4 years) | 116 | 114 | 1 (referent) | 0.80 (0.54–1.17) | |

| Cancer stage | .54 | ||||

| Localized | 91 | 83 | 1 (referent) | 1.11 (0.71–1.74) | |

| Locally advanced | 46 | 43 | 1 (referent) | 0.93 (0.50–1.75) | |

| Metastatic | 328 | 327 | 1 (referent) | 0.84 (0.66–1.07) | |

HR, hazard ratio.

The Cox proportional hazards model was adjusted for the following covariates except for the stratification variable: age at diagnosis (continuous), cohort (sex), race/ethnicity (white, black, other, or unknown), year of diagnosis (2000–2005 or 2006–2013), smoking status (never, past, current, or unknown), body mass index (continuous), and diabetes status (no, recent-onset, or long-standing).

Discussion

To test the hypothesis that pre-diagnosis statin use is associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, we conducted a large prospective study that included over 600 patients with pancreatic cancer and detailed information on pre-diagnosis statin use. Compared with non-regular statin users before diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, we found an approximate 20% reduction in the hazards for overall mortality among regular statin users. Although studies suggest that regular use of aspirin or angiotensin system inhibitors may reduce incidence and mortality of pancreatic cancer,26–28 pre-diagnosis statin use appeared to associate with longer patient survival independent of these medications.

In line with previous retrospective analyses,12–16,33,34 our large prospective study identified improved survival among patients with pancreatic cancer who regularly used statins. Interestingly, in a recent study of 2,142 U.S. patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, any statin use (before or after diagnosis) was associated with improved overall survival compared to non-statin use (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79–0.97), independent of cholesterol levels.12 This study supports a potential lipid-independent mechanism by which statins may impact mortality in pancreatic cancer. Nevertheless, a small randomized trial of statin use with chemotherapy has been performed in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. In this trial of 114 patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer, simvastatin failed to demonstrate a survival benefit when added to single-agent gemcitabine.35 However, a low dose of simvastatin was administered, and multi-agent chemotherapy programs have become the standard of care for advanced pancreatic cancer, rather than single-agent gemcitabine.36

Statins inhibit the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, which suppresses intracellular cholesterol synthesis, thereby reducing intermediate isoprenoids that serve as post-translational regulators of proteins involving the cell cycle and proliferation.6,37 The downstream proteins which are potentially suppressed by statins include RAS and the Rho family of proteins, which are strongly implicated in carcinogenesis.7,11 Along with inhibition of multiple signaling pathways involved in cell growth (RAF/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/MTOR pathways),8,38 statins may also suppress cell proliferation and angiogenesis as well as induce apoptosis in cancer cells.5,6,8 In mouse models of pancreatic cancer, simvastatin and atorvastatin suppressed formation and progression of pancreatic neoplasms,39 potentially through down-regulation of the RAS protein.40 Evidence also points to immunomodulatory effects of statins as an alternative mechanism for cancer suppression, as statins may enhance the reactivity of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment.7,8 Notably, statin use reported within the 2 years of pancreatic cancer diagnosis was most strongly associated with patient survival. Given studies suggesting no chemopreventative effects of statins on incidence of pancreatic cancer,41–43 statins may exert greater anti-tumor properties at a later phase of tumor development or after clinical manifestation. Further studies are warranted to investigate temporal changes in suppressive effects of statins on neoplastic cells during the evolution of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Limitations of the current study should be considered. We did not analyze data on the specific statin medication used, post-diagnosis statin use, or the dosage and frequency beyond the patient’s report of regular use. Our cohort studies collect limited data on cancer treatments, and chemotherapy regimens for our patients were not known. Nonetheless, statin use is unlikely to be associated with choice of treatment program, and chemotherapy options available during the study were primarily limited to 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid or gemcitabine. In addition, our findings remained consistent after adjustment for cancer stage and year of diagnosis by which treatment strategies were largely determined. We used overall mortality as the primary study endpoint rather than pancreatic cancer-specific mortality. However, pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal malignancy,1 and the majority of patients die from this disease, such that overall mortality is considered as a reasonable surrogate for clinical outcomes in pancreatic cancer. Though we cannot rule out the possibility of unmeasured confounding, our multivariable models included multiple known and potential variables associated with pancreatic cancer survival, and this adjustment did not significantly alter our results. If patients regularly taking statins received closer medical attention, then it is possible that the diagnosis was made earlier with the potential for more aggressive therapy and longer survival. Finally, our study participants were predominately white populations. Therefore, further investigation on the influence of pre-diagnosis statin use on pancreatic cancer survival in more racially diverse populations is warranted.

Our study also has several notable strengths, including a prospective study design and large sample size with over 600 pancreatic cancer cases. Importantly, our study population consisted of patients with all stages of pancreatic cancer diagnosed in hospitals throughout the U.S., increasing the generalizability of our findings. Notably, survival times for patients in the current study were highly similar to those reported in the National Cancer Database,44 suggesting that our cohort acts as a reasonable approximation of the general population of pancreatic cancer patients in the United States. Prospectively collected data allowed us to examine the long-term effects of pre-diagnosis statin use on patient survival without substantial recall bias, to rigorously adjust for potential confounders, and to evaluate for effect modification by other prognostic factors.

In conclusion, regular statin use before diagnosis was associated with improved survival among patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma in 2 large U.S. cohorts followed prospectively over more than 10 years of follow-up. Given overall low rates of serious adverse events with statin use11 and plausible biological mechanisms for their anti-tumor properties, statin use should be considered for further study in pancreatic cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of the data.

Grant Support: The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) is supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: UM1 CA186107, P01 CA87969, and R01 CA49449. The Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) is supported by NIH UM1 CA167552. This work was additionally supported by NIH R01 CA205406 and the Broman Fund for Pancreatic Cancer Research to K.N.; by the Robert T. and Judith B. Hale Fund for Pancreatic Cancer, Perry S. Levy Fund for Gastrointestinal Cancer Research, Pappas Family Research Fund for Pancreatic Cancer, NIH R01 CA124908, and NIH P50 CA127003 to C.S.F.; by NIH R35 CA197735 to S.O.; and by Hale Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research, NIH/National Cancer Institute (NCI) U01 CA210171, Department of Defense CA130288, Lustgarten Foundation, Pancreatic Cancer Action Network, Noble Effort Fund, Peter R. Leavitt Family Fund, Wexler Family Fund, and Promises for Purple to B.M.W.. T.H. was supported by a fellowship grant from the Mitsukoshi Health and Welfare Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A

- HPFS

Health Professionals Follow-up Study

- HR

hazard ratio

- NHS

Nurses’ Health Study

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions: Drafting the manuscript: Tsuyoshi Hamada, Natalia Khalaf, Chen Yuan, and Brian M. Wolpin; planning and conducting the study: Tsuyoshi Hamada, Natalia Khalaf, Chen Yuan, Vicente Morales-Oyarvide, Ana Babic, Zhi Rong Qian, Charles S. Fuchs, Shuji Ogino, and Brian M. Wolpin; collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data: all authors; editing the manuscript: Vicente Morales-Oyarvide, Ana Babic, Jonathan A. Nowak, Zhi Rong Qian, Kimmie Ng, Douglas A. Rubinson, Peter Kraft, Edward L. Giovannucci, Meir J. Stampfer, Charles S. Fuchs, Shuji Ogino, and Brian M. Wolpin; supervising the study: Charles S. Fuchs, Shuji Ogino, and Brian M. Wolpin; approving the final submitted draft: all authors.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chari ST, Leibson CL, Rabe KG, et al. Pancreatic cancer-associated diabetes mellitus: prevalence and temporal association with diagnosis of cancer. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:95–101. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matusewicz L, Meissner J, Toporkiewicz M, et al. The effect of statins on cancer cells–review. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:4889–4904. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3551-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullen PJ, Yu R, Longo J, et al. The interplay between cell signalling and the mevalonate pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:718–731. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demierre MF, Higgins PD, Gruber SB, et al. Statins and cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:930–942. doi: 10.1038/nrc1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisanti S, Picardi P, Ciaglia E, et al. Novel prospects of statins as therapeutic agents in cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2014;88:84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emberson JR, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, et al. Lack of effect of lowering LDL cholesterol on cancer: meta-analysis of individual data from 175,000 people in 27 randomised trials of statin therapy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Statin use and reduced cancer-related mortality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1792–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gronich N, Rennert G. Beyond aspirin-cancer prevention with statins, metformin and bisphosphonates. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:625–642. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang BZ, Chang JI, Li E, et al. Influence of Statins and Cholesterol on Mortality Among Patients With Pancreatic Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djw275. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HS, Lee SH, Lee HJ, et al. Statin Use and Its Impact on Survival in Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3607. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu BU, Chang J, Jeon CY, et al. Impact of statin use on survival in patients undergoing resection for early-stage pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1233–1239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeon CY, Pandol SJ, Wu B, et al. The association of statin use after cancer diagnosis with survival in pancreatic cancer patients: a SEER-medicare analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.E JY, Lu SE, Lin Y, et al. Differential and Joint Effects of Metformin and Statins on Overall Survival of Elderly Patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A Large Population-Based Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:1225–1232. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birmann BM, Barnard ME, Bertrand KA, et al. Nurses’ Health Study Contributions on the Epidemiology of Less Common Cancers: Endometrial, Ovarian, Pancreatic, and Hematologic. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1608–1615. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giovannucci E, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, et al. Physical activity, obesity, and risk for colon cancer and adenoma in men. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:327–334. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-5-199503010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Y, Nishihara R, Wu K, et al. Population-wide Impact of Long-term Use of Aspirin and the Risk for Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:762–769. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai CJ, Leitzmann MF, Willett WC, et al. Statin use and the risk of cholecystectomy in women. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1593–1600. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JE, Baba Y, Ng K, et al. Statin use and colorectal cancer risk according to molecular subtypes in two large prospective cohort studies. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1808–1815. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamada T, Cao Y, Qian ZR, et al. Aspirin Use and Colorectal Cancer Survival According to Tumor CD274 (Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1) Expression Status. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1836–1844. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalaf N, Yuan C, Hamada T, et al. Regular Use of Aspirin or Non-Aspirin Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Is Not Associated With Risk of Incident Pancreatic Cancer in Two Large Cohort Studies. Gastroenterology. 2017 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang T, Poole EM, Eliassen AH, et al. Hypertension, use of antihypertensive medications, and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:291–299. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the National Death Index and Equifax Nationwide Death Search. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:1016–1019. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Archibugi L, Piciucchi M, Stigliano S, et al. Exclusive and Combined Use of Statins and Aspirin and the Risk of Pancreatic Cancer: a Case-Control Study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:13024. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song T, Choi CH, Kim MK, et al. The effect of angiotensin system inhibitors (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers) on cancer recurrence and survival: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2017;26:78–85. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Ijichi H, et al. Inhibition of renin-angiotensin system affects prognosis of advanced pancreatic cancer receiving gemcitabine. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1644–1648. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makuch RW. Adjusted survival curve estimation using covariates. J Chronic Dis. 1982;35:437–443. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghali WA, Quan H, Brant R, et al. Comparison of 2 methods for calculating adjusted survival curves from proportional hazards models. JAMA. 2001;286:1494–1497. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.12.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 32.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozak MM, Anderson EM, von Eyben R, et al. Statin and Metformin Use Prolongs Survival in Patients With Resectable Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas. 2016;45:64–70. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Sasaki T, et al. Clinical outcomes of chemotherapy for diabetic and nondiabetic patients with pancreatic cancer: better prognosis with statin use in diabetic patients. Pancreas. 2013;42:202–208. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31825de678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong JY, Nam EM, Lee J, et al. Randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase II trial of simvastatin and gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:125–130. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubinson DA, Wolpin BM. Therapeutic Approaches for Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2015;29:761–776. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gazzerro P, Proto MC, Gangemi G, et al. Pharmacological actions of statins: a critical appraisal in the management of cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:102–146. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.004994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohammed A, Qian L, Janakiram NB, et al. Atorvastatin delays progression of pancreatic lesions to carcinoma by regulating PI3/AKT signaling in p48Cre/+ LSL-KrasG12D/+ mice. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1951–1962. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fendrich V, Sparn M, Lauth M, et al. Simvastatin delay progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer formation in a genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2013;13:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao J, Chung YT, Yang AL, et al. Atorvastatin inhibits pancreatic carcinogenesis and increases survival in LSL-KrasG12D-LSL-Trp53R172H-Pdx1-Cre mice. Mol Carcinog. 2013;52:739–750. doi: 10.1002/mc.21916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cui X, Xie Y, Chen M, et al. Statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1099–1111. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon MS, Desai P, Wallace R, et al. Prospective analysis of association between statins and pancreatic cancer risk in the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:415–423. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0717-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamada T, Khalaf N, Yuan C, et al. Statin use and pancreatic cancer risk in two prospective cohort studies. J Gastroenterol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1430-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, et al. Validation of the 6th edition AJCC Pancreatic Cancer Staging System: report from the National Cancer Database. Cancer. 2007;110:738–744. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.