Abstract

Goals

To determine patient preference for Barrett’s esophagus (BE) screening techniques.

Background

Sedated endoscopy (sEGD) and unsedated transnasal endoscopy (uTNE) are both potential techniques for BE screening. However systematic assessment of patient preference for these two techniques is lacking. As part of a comparative effectiveness randomized trial of BE screening modalities, we measured short-term patient preferences for the following approaches: in-clinic unsedated transnasal endoscopy (huTNE), mobile-based transnasal endoscopy (muTNE) and sEGD using a novel assessment instrument.

Study

Consenting community patients without known BE were randomly assigned to receive huTNE, muTNE, or sEGD, followed by a telephone administered preference and tolerability assessment instrument 24 hours after study procedures. Patient preference was measured by the waiting trade-off method (WTO).

Results

201 patients completed screening with huTNE (n=71), muTNE (n=71) or sEGD (n=59) and a telephone interview. Patients’ preferences for sEGD and uTNE using the WTO method were comparable (P=0.51). While tolerability scores were superior for sEGD (P<0.001) compared to uTNE, scores for uTNE examinations were acceptable.

Conclusions

Patient preference is comparable between sEGD and uTNE for diagnostic examinations conducted in an endoscopy suite or in a mobile setting. Given acceptable tolerability, uTNE may be a viable alternative to sEGD for BE screening.

Keywords: Barrett’s Esophagus, Patient Preferences, Screening, Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Barrett’s esophagus (BE), a well-known complication of gastroesophageal reflux (GER), is the key precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Identifying effective approaches for the early detection of BE and BE related dysplasia has the potential to identify and subsequently enroll patients in appropriate surveillance programs to enable detection of dysplasia before progression to EAC. Treatment with endoscopic modalities has been shown to decrease the risk of progression of dysplastic BE to EAC in addition to treating early stage EAC successfully.1, 2

One of the important impediments to BE screening is the lack of a cost effective, and widely applicable screening technique. Sedated esophagogastroduodenoscopy (sEGD) has substantial direct healthcare costs as well as indirect costs limiting its wide application as a BE screening tool. To overcome this challenge, there has been an effort to develop unsedated and minimally invasive methods of screening for BE such as unsedated transnasal endoscopy (uTNE).3, 4

Randomized prospective studies and a meta-analysis comparing these techniques using post procedural questionnaires to evaluate symptoms and tolerability have been reported, showing that while traditional sEGD can result in less pain, both methods are well tolerated.5, 6 There have also been studies looking at more objective measures for tolerability, including blood pressure and pulse measurements as surrogates for sympathetic response during the procedure.7 These have shown that there is less sympathetic activation during transnasal endoscopy.8 More recently, uTNE has been shown to be effective in diagnosing early malignancy.9 Finally, this technique has proven to be easy to adopt.10

As part of a comparative effectiveness trial to compare various modalities for screening for BE, we evaluated participant tolerance and preference for those undergoing in-clinic unsedated transnasal endoscopy (huTNE), mobile-based (muTNE) and traditional sEGD. To measure patient preferences, we utilized a novel preference-based valuation method called the waiting trade off (WTO) method. The existing patient preference data in the literature is based on the commonly used valuation method of rating scales to compare different methods of upper endoscopy, which has several limitations.5, 6 We aimed to obtain patient preference data that truly reflects the patients’ attitudes towards these screening techniques by using the WTO method.11 This is important because capturing patient short-term health related quality of life (HRQL) may change the overall HRQL for a health intervention, in this case upper endoscopy and uTNE.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. This study was performed in the context of a prospective, randomized controlled trial in Olmsted County, Minnesota that was conducted to evaluate the participation rates and comparative clinical effectiveness of sEGD and uTNE performed in an endoscopy suite and uTNE performed in a mobile van.12 In this study, using Rochester Epidemiology Project data on those that had previously completed a validated gastrointestinal symptom questionnaire from 1988 to 2009, a gender- and age-stratified random sample of Olmsted County residents were selected and then mailed an invitation to participate (150 in each group) in screening for BE.13–15 Those that agreed to participate in the screening method for which they were assigned (either huTNE, muTNE or sEGD) were asked if they would be willing to undergo the screening examination. Comparative effectiveness of these three techniques, measured by participation rates, yield of findings, quality of examination and safety were assessed and were found to be similar.12

The TNE-5000 Endosheath transnasal esophagoscope (Vision Sciences, Orangeburg, NY), a commercially available, flexible video esophagoscope (TNE-5000, Vision Sciences of Orangeburg, NY) was used for both the huTNE and muTNE examinations. This device has a shaft diameter of 4.7 by 5.8 mm, has an accessory channel that is 2.1 mm and is able to angulate in two directions. [see Figure 1] Before the procedure, local anesthesia was administered to the nares with a topical spray of lidocaine with the vasoconstrictor such as oxymetazoline.16 The procedure was done with the patient in a left lateral position, and once the endoscope was lubricated it was introduced into the nasal passage and advanced along the floor of the nasopharyngeal space or between the middle and inferior turbinate. Once in the oropharynx, the procedure is carried out in a similar fashion to traditional sEGD. An endoscopy technician was available to help with patient positioning.

Figure 1.

TNE-5000 (Vision Sciences of Orangeburg, NY) hand controls (left) and size comparison with the standard Olympus GIF-H180 (Center Valley, PA) (right).

Sedated endoscopy was performed with standard endoscopic equipment and sedation. These patients were sedated with a combination of opiate analgesia and benzodiazepine. Once sedated, the video gastroscope (Olympus GIF-H180, Center Valley, PA) was introduced into their oral cavity and advanced to the oropharynx and into the esophagus. Sedation was administered by a registered nurse under the direction of the physician and an endoscopy technician was also involved in patient positioning. Following this, the patient needed a chaperone to accompany them home. The sEGD and huTNE arms were conducted in the clinical research unit of the Mayo Center for Clinical and Translational Science, which has a fully equipped endoscopy suite. uTNE in the mobile arm of the study was conducted in a mobile research van. Both huTNE and muTNE were performed in a similar manner.

All patients were contacted via phone by a trained interviewer (JE) to administer the preference-based evaluation tool using the waiting trade off (WTO) method 24 hours after the procedure.17 As part of the WTO, patients were asked that if they were to receive the ideal screening procedure (without pain, lost time and anxiety), how long would they be willing to wait for the results of or treatment from that procedure compared to how long they were willing to wait to receive the results or evaluation from the method of screening they actually underwent. The WTO provides a short-term patient preference (similar to quality-adjusted life years) to reflect the morbidity of the screening test and is reported as waiting trade-off time (days). This tool is a variation of the time trade off (TTO) technique for valuing short-term quality of life. It is designed to value health states associated with diagnostic screening and testing and provides a more accurate representation of patient preference, while still being economically feasible to perform. The longer a participant is willing to wait for the results or treatment after the ‘ideal’ test or procedure, the more they are willing to avoid the procedure that they actually had and consider it less desirable. Additionally, a tolerability questionnaire was also administered. Patients were asked to rank, on a 0–10 scale (0 = best, 10 = worst), the following aspects of the procedure to assess tolerability: pain, choking, gagging, anxiety and overall tolerability.5 Patients were also asked if they would undergo the uTNE procedure again for BE screening.

Statistical Analysis

The ANOVA test was used to compare the tolerability scores and patient preferences between the three groups and a t test or chi square test were used to compare characteristics of uTNE patients to sEGD patients using the JMP® 10.0.0 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc, Raleigh, NC).

RESULTS

209 patients underwent screening procedures in the trial. Data on tolerability and patient preference were collected in 201 (96%). There were 8 patients who could not be reached. 94 (47%) patients were men, with a mean age of 70 years (range: 54 to 87 years). Tolerability and WTO responses were available in 59 patients undergoing sEGD (97%), 71 patients undergoing huTNE (99%) and 71 patients undergoing muTNE (93%). Baseline characteristics of these participants with tolerability data were largely comparable (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the three groups studied

| Variable | muTNE (n=71) | huTNE (n=71) | sEGD (n=59) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 66 (9) | 64 (9) | 66 (9) |

| Male gender | 30 (42.2%) | 35 (49.3%) | 28 (47.5%) |

| White ethnicity | 68 (95.8%) | 71 (100%) | 59 (100%) |

| BMI | 28.7 (5.4) | 28.8 (4.99) | 289.3 (5.34) |

| Waist to hip ratio | 0.91 (0.09) | 0.92 (0.11) | 0.91 (0.09) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 2 (2.9%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| High school or some college | 34 (48.6%) | 39 (54.9%) | 31 (53.4%) |

| College/professional training | 34 (48.6%) | 31 (43.7%) | 26 (44.8%) |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 20 (28.6%) | 28 (39.4%) | 17 (29.3%) |

| Unemployed/homemaker | 6 (8.6%) | 6 (8.4%) | 4 (6.9%) |

| Retired | 44 (62.9%) | 37 (52.1%) | 37 (63.8%) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 55 (78.6%) | 61 (85.9%) | 41 (70.7%) |

| Not married | 15 (21.4%) | 10 (14.1%) | 17 (29.3%) |

| Frequency of reflux symptoms | |||

| ≥1/week | 9 (12.7%) | 11 (15.5%) | 8 (13.6%) |

| <1/week | 24 (33.8%) | 32 (45.1%) | 28 (47.5%) |

| None | 38 (53.5%) | 28 (39.4%) | 23 (39.0%) |

| Current use PPI drugs | 13 (18.3%) | 9 (12.7%) | 11 (18.6%) |

| Current aspirin use | 34 (47.8%) | 37 (52.1%) | 35 (59.3%) |

| Symptom somatization score | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.5) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.9 (1.4) | 1.3 (2.0) |

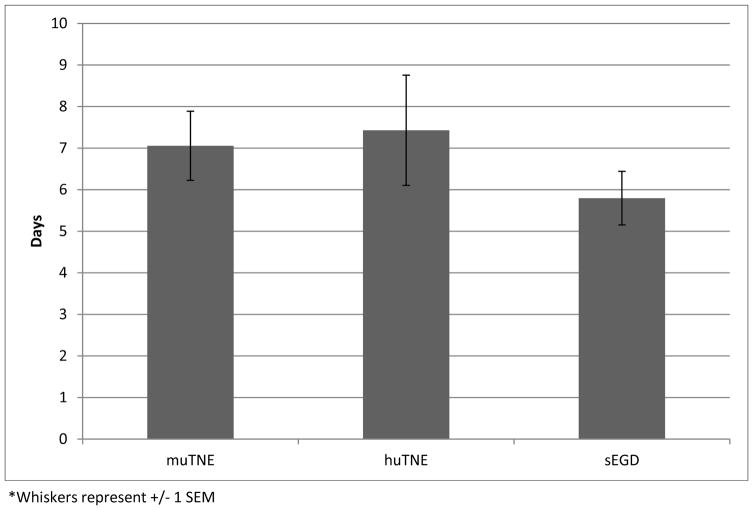

The WTO and questionnaire scores are reported in Table 2. Even though the statistically significant differences in patient-reported tolerability scores above appear to favor sEGD, the vast majority (84%) of patients who underwent uTNE reported that they would be willing to undergo the uTNE procedure again. All patients in the sEGD arm also reported willingness to repeat sEGD. This willingness to undergo the uTNE procedure again was supported by assessing the WTO scores (in days). When comparing all three groups, there was no difference in WTO scores (P=0.5126) (see Figure 2). The mean number of days a patient who received sEGD was willing to wait was 5.8. This was not statistically different from the number of days that a patient who received huTNE was willing to wait, at 7.4 (P=0.3339, 95% CI: −1.59 to 4.66) or from those who received muTNE, who were willing to wait, 7.1 days (P=0.2903, 95% CI: −1 to 3.32). [see Figure 2]

Table 2.

Pain, overall tolerability, gagging, choking, anxiety scores and waiting trade off (in days) in the three groups studied

| muTNE (N=71) | huTNE (N=71) | sEGD (N=59) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waiting Trade Off (days) | |||

| Mean (SEM) | 7.1 (0.8) | 7.4 (1.3) | 5.8 (0.65) |

| P-Value Comparing All Groups: 0.5126 | |||

|

| |||

| Pain (Scale 0–10 with 10 being most painful) | |||

| Mean (SEM) | 2 (0.2) | 2.8 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.1) |

| P-Value Comparing All Groups: <0.0001 | |||

|

| |||

| Overall Tolerability (Scale 1–10 with 10 being least tolerable) | |||

| Mean (SEM) | 1.9 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.1) |

| P-Value Comparing All Groups: <0.0001 | |||

|

| |||

| Gagging (Scale 1–10 with 10 being maximal) | |||

| Mean (SEM) | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.1) |

| P-Value Comparing All Groups: 0.001 | |||

|

| |||

| Choking (Scale 1–10 with 10 being maximal) | |||

| Mean (SEM) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| P-Value Comparing All Groups: 0.0034 | |||

|

| |||

| Anxiety (Scale 1–10 with 10 being maximal) | |||

| Mean (SEM) | 2.7 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.2) |

| P-Value Comparing All Groups: <0.0001 | |||

muTNE: Unsedated transnasal endoscopy done in mobile research unit

huTNE: Unsedated transnasal endoscopy done in the clinic

sEGD: Traditional sedated EGD

Figure 2.

Comparison of Mean Waiting Trade-Off Time

DISCUSSION

Given the rising incidence of EAC in the United States, it is critical that an acceptable and well tolerated screening tool for Barrett’s esophagus is developed. Currently, sedated EGD is the standard method of assessing reflux complications and symptoms in the United States. The current reported adverse outcomes and fatalities are 0.54% and 0.03%, respectively, in patients undergoing EGD and 50% to 60% of these are related to the use of conscious sedation with a benzodiazepine and opiate analgesic.18, 19 This method of has other disadvantages including the need for close monitoring during and post-procedure, increased sympathetic nervous system stress, increased cardiovascular stress and need for specialized nursing care. 8, 20, 21 In addition to high direct costs, indirect costs such as loss of work for the patient and the caregiver are also incurred with sEGD.22 In a randomized trial we have previously demonstrated comparable clinical effectiveness, safety, diagnostic yield and imaging quality with uTNE and sEGD.12, 23 However, uTNE continues to be underutilized for BE screening due to perceived patient and provider lack of preference despite randomized studies showing comparable patient tolerance between both sedated EGD and unsedated TNE,.5, 6, 24 In this randomized community based study we have carefully assessed comparable patient preference for BE screening with sEGD and uTNE using a valid tool and demonstrated the lack of a statistically significant difference in patient preference for both techniques. Indeed the WTO scores appeared to indicate superior patient preference for uTNE, though the difference was not statistically significant. Additionally while the tolerability scores were numerically lower (difference being statistically significant) in the sEGD group than the uTNE groups, they were still adequate for clinical use.

The WTO method of measuring preference has the advantage of being more intuitive to the study participants. This form of measuring patient preference has been previously studied successfully in assessing treatment choice in women undergoing different types of uterine fibroid treatments (abdominal hysterectomy, magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound surgery, and uterine artery embolization).25 It has also been used to assess preference for a diagnostic tool in women who undergo breast biopsies (surgical, needle core biopsy or both) as part of evaluation of breast nodules and in different diagnostic tools for cerebrovascular disease.26, 27

It is possible that some bias exist due to the study design. This may stem from patients being contacted for participation after randomization to a technique of screening. However this is likely to be small given the overall comparable nature of the three groups at the time of contact and participation (table 1). This study design was chosen to specifically assess participation rates in three groups separately and subsequently compare preference assessed by the WTO method in the three groups. EGD is usually performed with conscious sedation in the United States and hence our results may be less applicable to countries where it is routinely performed without sedation. Additionally, the use of a single trained interviewer for all calls was helpful in standardizing the script and explanations for all participants. While the concept is thought to be intuitive, explanation and reiteration of the concept by an experienced interviewer was crucial in keeping the results generalizable.

While all three techniques were overall well tolerated by patients, sEGD appeared to be best tolerated when using the rating scale method of health state valuation. This is likely due to the use of analgesic and amnestic sedation with this procedure. Using the WTO assessment tool as a more precise measure of patient preference, we found that there was no statistically significant difference between patient preference for sEGD and uTNE (performed in an endoscopy suite or in a mobile van). This suggests that patient preference may not be a significant factor when utilizing uTNE as an alternative to traditional sedated EGD for BE screening. When combined with lower direct and indirect costs and comparable clinical effectiveness, the rationale for the use of unsedated minimally invasive tools for BE screening is further strengthened.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: Funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant RC4DK090413) and the Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences. This publication was made possible by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any disclosures regarding this study.

References

- 1.Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, Wolfsen HC, Sampliner RE, Wang KK, Galanko JA, Bronner MP, Goldblum JR, Bennett AE, Jobe BA, Eisen GM, Fennerty MB, Hunter JG, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ, Rothstein RI, Gordon SR, Mashimo H, Chang KJ, Muthusamy VR, Edmundowicz SA, Spechler SJ, Siddiqui AA, Souza RF, Infantolino A, Falk GW, Kimmey MB, Madanick RD, Chak A, Lightdale CJ. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2277–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, Gerson LB. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:30–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorbi D, Chak A. Unsedated EGD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:102–10. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaker R. Unsedated trans-nasal pharyngo esophagogastroduodenoscopy (T-EGD): technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:346–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaman A, Hahn M, Hapke R, Knigge K, Fennerty MB, Katon RM. A randomized trial of peroral versus transnasal unsedated endoscopy using an ultrathin videoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:279–84. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murata A, Akahoshi K, Sumida Y, Yamamoto H, Nakamura K, Nawata H. Prospective randomized trial of transnasal versus peroral endoscopy using an ultrathin videoendoscope in unsedated patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:482–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sami SS, Subramanian V, Ortiz-Fernandez-Sordo J, Saeed A, Singh S, Guha IN, Iyer PG, Ragunath K. Performance characteristics of unsedated ultrathin video endoscopy in the assessment of the upper GI tract: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:782–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kataoka H, Hayano J, Mizushima T, Tanaka M, Kubota E, Shimura T, Mizoshita T, Tanida S, Kamiya T, Nojiri S, Mukai S, Mizuno K, Joh T. Cardiovascular tolerance and autonomic nervous responses in unsedated upper gastrointestinal small-caliber endoscopy: a comparison between transnasal and peroral procedures with newly developed mouthpiece. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:78–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shariff MK, Bird-Lieberman EL, O’Donovan M, Abdullahi Z, Liu X, Blazeby J, Fitzgerald R. Randomized crossover study comparing efficacy of transnasal endoscopy with that of standard endoscopy to detect Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:954–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maffei M, Dumortier J, Dumonceau JM. Self-training in unsedated transnasal EGD by endoscopists competent in standard peroral EGD: prospective assessment of the learning curve. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:410–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazier J, Deverill M, Green C, Harper R, Booth A. A review of the use of health status measures in economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3:i–iv. 1–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sami SS, Dunagan KT, Johnson ML, Schleck CD, Shah ND, Zinsmeister AR, Wongkeesong LM, Wang KK, Katzka DA, Ragunath K, Iyer PG. A randomized comparative effectiveness trial of novel endoscopic techniques and approaches for Barrett’s esophagus screening in the community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:148–58. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung KW, Talley NJ, Romero Y, Katzka DA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Dunagan KT, Lutzke LS, Wu TT, Wang KK, Frederickson M, Geno DM, Locke GR, Prasad GA. Epidemiology and natural history of intestinal metaplasia of the gastroesophageal junction and Barrett’s esophagus: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1447–55. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.130. quiz 1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. A new questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:539–47. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halder SL, Locke GR, 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, 3rd, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:799–807. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blevins CH, Iyer PG. Putting it Through the Nose: The Ins and Outs of Transnasal Endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1371–1373. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swan JS, Fryback DG, Lawrence WF, Sainfort F, Hagenauer ME, Heisey DM. A time-tradeoff method for cost-effectiveness models applied to radiology. Med Decis Making. 2000;20:79–88. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0002000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faulx AL, Catanzaro A, Zyzanski S, Cooper GS, Pfau PR, Isenberg G, Wong RC, Sivak MV, Jr, Chak A. Patient tolerance and acceptance of unsedated ultrathin esophagoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:620–3. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.123274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan MF. Complications of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:287–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mori A, Ohashi N, Tatebe H, Maruyama T, Inoue H, Takegoshi S, Kato T, Okuno M. Autonomic nervous function in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a prospective randomized comparison between transnasal and oral procedures. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:38–44. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2124-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yagi J, Adachi K, Arima N, Tanaka S, Ose T, Azumi T, Sasaki H, Sato M, Kinoshita Y. A prospective randomized comparative study on the safety and tolerability of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1226–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-921037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moriarty JP, Shah ND, Rubenstein JH, Blevins CH, Johnson M, Katzka DA, Wang KK, Wongkeesong LM, Ahlquist DA, Iyer PG. Costs associated with Barrett’s esophagus screening in the community: an economic analysis of a prospective randomized controlled trial of sedated versus hospital unsedated versus mobile community unsedated endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crews NR, Gorospe EC, Johnson ML, Wong Kee Song LM, Katzka DA, Iyer PG. Comparative quality assessment of esophageal examination with transnasal and sedated endoscopy. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E340–E344. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-122008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atkinson M, Das A, Faulx A, Kinnard M, Falck-Ytter Y, Chak A. Ultrathin esophagoscopy in screening for Barrett’s esophagus at a Veterans Administration Hospital: easy access does not lead to referrals. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:92–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fennessy FM, Kong CY, Tempany CM, Swan JS. Quality-of-life assessment of fibroid treatment options and outcomes. Radiology. 2011;259:785–92. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11100704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swan JS, Sainfort F, Lawrence WF, Kuruchittham V, Kongnakorn T, Heisey DM. Process utility for imaging in cerebrovascular disease. Acad Radiol. 2003;10:266–74. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swan JS, Lawrence WF, Roy J. Process utility in breast biopsy. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:347–59. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06290490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]