Abstract

Background

Measurement of insulin and C-peptide concentrations is important for deciding whether insulin treatment is required in diabetic patients. We aimed to investigate the analytical performance of insulin and C-peptide assays using the Lumipulse G1200 system (Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Methods

We examined the precision, linearity, and cross-reactivity of insulin and C-peptide using five insulin analogues and purified proinsulin. A method comparison was conducted between the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) systems in 200 diabetic patients on insulin treatment. Reference intervals for insulin and C-peptide concentrations were determined in 279 healthy individuals.

Results

For insulin and C-peptide assays, within-laboratory precision (% CV) was 3.78–4.14 and 2.89–3.35%, respectively. The linearity of the insulin assay in the range of 0–2,778 pmol/L was R2=0.9997, and that of the C-peptide assay in the range of 0–10 nmol/L was R2=0.9996. The correlation coefficient (r) between the Roche E170 and Lumipulse G1200 results was 0.943 (P<0.001) for insulin and 0.996 (P<0.001) for C-peptide. The mean differences in insulin and C-peptide between Lumipulse G1200 and the Roche E170 were 19.4 pmol/L and 0.2 nmol/L, respectively. None of the insulin analogues or proinsulin showed significant cross-reactivity with the Lumipulse G1200. Reference intervals of insulin and C-peptide were 7.64–70.14 pmol/L and 0.17–0.85 nmol/L, respectively.

Conclusions

Insulin and C-peptide tests on the Lumipulse G1200 show adequate analytical performance and are expected to be acceptable for use in clinical areas.

Keywords: C-peptide, Diabetes mellitus, Insulin, Lumipulse G1200, Performance

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a major chronic disease with increasing global prevalence [1]. The prevalence of diabetes among adults over 30 years in Korea has increased greatly, from 1.5% to 12.4% over the past 40 years, and is expected to grow two-fold by 2050. Among diabetes patients, the proportion of type 1 diabetes is approximately 0.22–1.19% [2,3].

There is currently no cure for diabetes, and clinical presentation and disease progression may vary considerably between types [4]. A correct diagnosis is important because the optimal treatment depends on the type of diabetes; furthermore, initial clinical diagnosis is rarely changed [4,5,6]. Although a gold standard for differentiating the types of diabetes has not been established, serum insulin and C-peptide concentrations provide diagnostic information on insulin deficiency (type 1 diabetes) or insulin resistance (type 2 diabetes) through estimation of insulin secretion [4,5,7,8]. In insulin-treated patients, the measurement of endogenous insulin secretion may aid in predicting the degree of postprandial hyperglycemia and the likely response to prandial insulin [9]. In addition, it is helpful for evaluating insulin therapy compliance and suspected insulin overdose [10,11].

C-peptide is used as a diagnostic marker for diabetes mellitus because it reflects endogenous insulin secretion even when the patient carries insulin antibodies or is insulin-treated [5]. Thus, accurate measurement of serum insulin and C-peptide concentrations is very helpful in the initial diagnosis of the diabetes type as well as in insulin-treated patients, but it is currently difficult. Cross-reactivity with insulin analogues may falsely inflate serum insulin measurements [12]. Further, an increase in proinsulin may not accurately reflect an increase in C-peptide [5,7]. Proinsulin and its partially processed forms, comprising fragments of insulin and C-peptide, can produce cross-reactivity as they are present in much higher concentrations [7]. Therefore, there is a need for reagents that do not react with the insulin analogues or proinsulin.

One potential option is the Lumipulse G1200 system (Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan), a robust mid-sized fully automated chemiluminescence-based enzyme immunoanalyzer that has been developed recently to measure insulin and C-peptide without the influence of insulin analogues and proinsulin. However, to our knowledge, its analytical performance in quantifying insulin and C-peptide concentrations has been rarely reported except an article in Japanese [13]. The Roche E170 system, an automated analyzer based on an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay, is used in many clinical laboratories to quantify human insulin and C-peptide concentrations [14]. To our knowledge, no study has compared the Lumipulse G1200 and the Roche E170 systems for insulin and C-peptide measurement.

We examined the analytical performance of the Lumipulse G1200 system for insulin and C-peptide assays. We also conducted a method comparison between the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems.

METHODS

1. Ethical approval

This retrospective study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea (IRB No: SMC 2015-01-071). The IRB waived the need for informed consent.

2. Systems and reagents

Test reagents for insulin and C-peptide have been developed and were provided by Fujirebio Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). These biomolecules can be measured by the Lumipulse G1200 system. Assay-specific anti-insulin monoclonal antibody (mouse) and anti-C-peptide monoclonal antibody (mouse) were used. Three quality control materials, Lyphochek Immunoassay Plus Control (40331, 40332, and 40333), with low, medium, and high concentrations of insulin and C-peptide, respectively, were supplied by Bio-Rad Laboratories (CA, USA). The limit of detection and limit of quantification were 1.74 pmol/L and 4.17 pmol/L for insulin and 0.001 nmol/L for C-peptide, respectively. The tests were conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions.

3. Study population

Diabetic patients who were undergoing insulin treatment and had visited Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, a tertiary care hospital, between March 2015 and May 2015, were enrolled. In total, 200 serum samples of diabetic patients (100 men and 100 women) were collected and analyzed retrospectively. The tests were performed using archival samples. Clinical information including age, sex, medical condition, and list of insulin analogues used in diabetic patients were obtained from electronic medical records. The median age was 63 years (range: 18–96 years). Six commercial preparations of insulin and insulin analogues were used, each with a concentration of 694.5 µmol/L: Humulin (Lilly, Basingstoke, UK), insulin aspart (Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark), insulin glargine (Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France), insulin lispro (Lilly), insulin detemir (Novo Nordisk), and insulin glulisine (Sanofi-Aventis).

In addition, 279 healthy subjects (123 men and 156 women; age: 19–78 years) who visited the health promotion center for regular health checkups were evaluated. The reference subjects were selected on the basis of medical examinations and current health status. We excluded pregnant subjects and those with high blood pressure; taking any medication; diagnosed as having diabetes or tuberculosis; presenting with fever; or testing positive for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus surface antigen, or hepatitis C virus antibodies. Hemolyzed blood samples, which can produce unreliable laboratory results, were excluded.

4. Method evaluation

1) Precision

Repeatability, between-run, and within-laboratory precision were evaluated by measuring pooled serum and two concentrations of Bio-Rad quality control materials for insulin and C-peptide, respectively. Each sample was evaluated twice per run, twice per day, for 20 consecutive days on the Lumipulse G1200 analyzer. The precision of insulin and C-peptide measurements was assessed according to the CLSI EP05-A3 guidelines [15].

2) Linearity

Samples containing a mixture of low (0 pmol/L, 0 nmol/L) and high (2,778 pmol/L, 10 nmol/L) concentrations of insulin and C-peptide, respectively, were analyzed using mixing ratios of 4:0, 3:1, 2:2, 1:3, and 0:4. To establish the regression equation, the measurements were repeated four times for each concentration of insulin and C-peptide. The linearity of insulin and C-peptide was assessed according to the CLSI EP06-A guidelines [16].

3) Method comparison

We measured insulin and C-peptide concentrations in 200 serum samples from diabetic patients and in 40 healthy subjects without insulin treatment. Analysis between the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) systems was conducted within one hour to avoid temporal changes in the samples. The method comparison was conducted according to the CLSI EP09-A2-IR guidelines [17].

4) Cross-reactivity

To evaluate the degree of cross-reactivity from insulin analogues and proinsulin, the five insulin analogues mentioned above (insulin aspart, insulin glargine, insulin lispro, insulin detemir, and insulin glulisine) and purified proinsulin (WHO International Standard 1st International Standard for Human Proinsulin NIBSC code: 09/296) were diluted in Lumipulse sample diluent. Insulin analogues and proinsulin were diluted to 6.94, 69.4, 694, and 6,940 pmol/L, and 100, 200, 1,000, and 2,000 nmol/L, respectively. The concentrations of insulin and C-peptide were measured using the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems in the same manner as the patient samples were measured for clinical diagnosis. All dilutions of each insulin analogue and proinsulin preparation were analyzed in duplicate, and the percentage cross-reactivity was calculated from the ratio of the measured and nominal concentrations.

5) Reference intervals

Serum samples from the 279 healthy adult subjects were used to determine reference intervals. To investigate whether reference intervals significantly differe by sex, we followed the CLSI C28-A3c guidelines [18].

5. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS v23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), MedCalc v11.5.1.0 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium), and Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Means and standard deviations were calculated. P values of less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. To evaluate precision, the CV was calculated. To evaluate linearity, the coefficient of determination (R2) was determined by logistic regression. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were calculated. The correlation of insulin with C-peptide concentrations was compared between the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems by calculating the differences in diabetic patients and healthy subjects. In addition, 95% limits of agreement for each comparison and the bias between the systems were evaluated using Bland–Altman analysis [19]. In cases involving cross-reactivity, clinical significance was tested for comparing the results to the reference change values (RCV) using the formula

[20],

where Z is the number of standard deviations appropriate for the given probability (1.96 for a probability of 95%), CVa is the analytical imprecision, and CVi is the estimate of within-subject biological variation.

In addition, we analyzed the concentration of insulin in patients treated with an insulin analogue that showed cross-reactivity. After assessment of normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, reference intervals were calculated using a non-parametric method: the reference limits were defined as the central 95th percentile of the healthy subjects. The lower reference limit was the 2.5th percentile, while the upper reference limit was the 97.5th percentile for healthy subjects.

RESULTS

1. Precision

Precision evaluation for insulin and C-peptide showed good repeatability and within-laboratory precision, with all CVs below 5% (Table 1).

Table 1. Precision of the Lumipulse G1200 system in measuring insulin and C-peptide.

| Test item | Concentration | Measurements (N) | Mean | SD | CV (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability | Between-run | Within-laboratory | |||||

| Insulin (pmol/L) | Low | 80 | 33.8 | 1.04 | 2.93 | 1.04 | 3.78 |

| Middle | 517 | 15.5 | 3.16 | 1.35 | 3.78 | ||

| High | 1,361 | 50.8 | 2.31 | 1.25 | 4.14 | ||

| C-peptide (nmol/L) | Low | 80 | 1.30 | 0.04 | 2.16 | 1.38 | 3.28 |

| Middle | 4.81 | 0.12 | 1.85 | 1.78 | 2.89 | ||

| High | 6.86 | 0.21 | 1.76 | 2.22 | 3.35 | ||

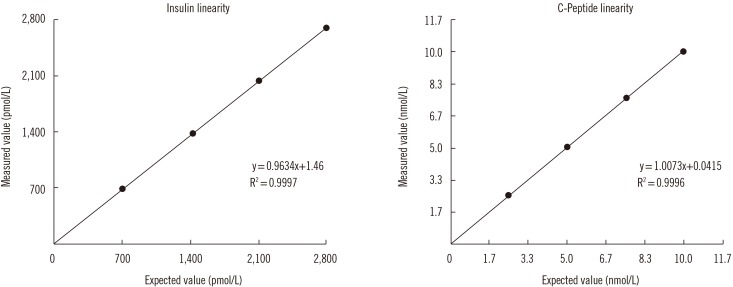

2. Linearity

The results of the linearity evaluation for insulin and C-peptide are presented in Fig. 1. The regression equation between the expected value (x) and the measured value using the Lumipulse G1200 (y) results was y=0.9634x+1.46 for insulin and y=1.0073x+0.0415 for C-peptide. The coefficient of determination (R2) for insulin (range: 0–2,778 pmol/L) in regression analysis was 0.9997, and that for C-peptide (range: 0–10 nmol/L) was 0.9996.

Fig. 1. Linearity of insulin and C-peptide in the Lumipulse G1200 system.

3. Method comparison

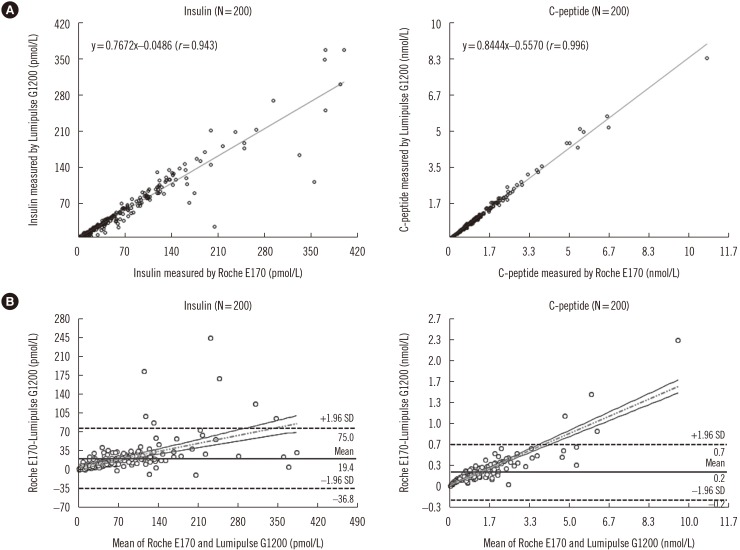

Insulin concentrations were lower when measured with the Lumipulse G1200 system than the Roche E170 system in diabetic patients (61.9±64.7 vs 81.3±79.9 pmol/L, P=0.008) and healthy subjects (31.0±13.1 vs 37.9±15.1 pmol/L, P=0.033). The concentrations of C-peptide in diabetic patients were not significantly different between the two systems (1.06±1.12 vs 1.28±1.33 nmol/L, P=0.077), while the Lumipulse G1200 yielded lower concentrations for healthy subjects (0.48±0.15 vs 0.60±0.17 nmol/L, P=0.001).

The r value between results obtained with the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems for insulin was 0.943 (P<0.001) and for C-peptide was 0.996 (P<0.001). The r value for insulin was less than 0.975, and therefore, an alternative method-comparison methodology, Bland–Altman difference analysis, was used. The Bland–Altman difference analysis revealed a mean bias of insulin between the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems from 200 patient samples of 19.4 pmol/L (95% confidence interval [CI]: −36.8–75.0 pmol/L) and of C-peptide of 0.2 nmol/L (95% CI: −0.2–0.7 nmol/L). The scatter plots, correlations, and differences between the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems for insulin and C-peptide are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Method comparison of the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems. (A) Correlations between insulin and C-peptide results. (B) Bland–Altman plot showing differences between insulin and C-peptide results.

4. Cross-reactivity

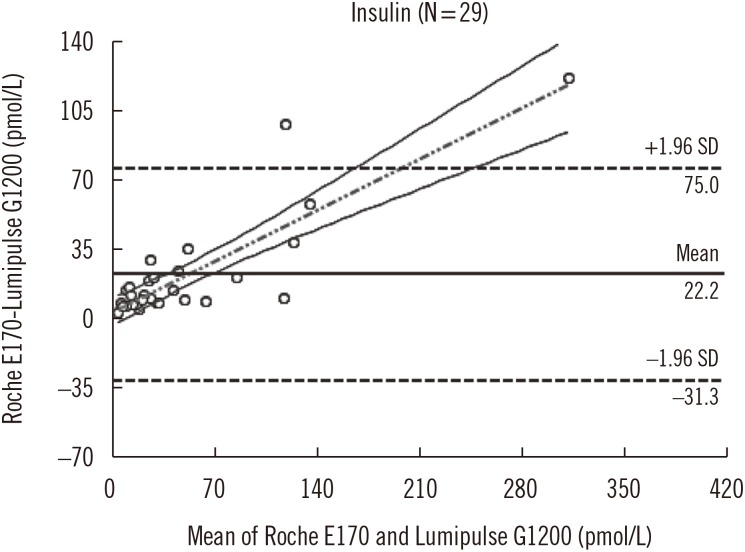

The measured concentration and calculated cross-reactivity for each of the stratified diluted insulin analogues are summarized in Table 2. None of the insulin analogues or proinsulin showed significant cross-reactivity, though there was slight cross-reactivity of insulin glargine in the Lumipulse G1200 system. However, the concentrations of insulin in patients treated with insulin glargine did not significantly differ from those in patients treated with other insulin analogues. Bland–Altman difference analysis of data from 29 samples of patients treated with insulin glargine (Fig. 3) revealed a mean difference of 22.2 pmol/L (95% CI: −31.3–75.0 pmol/L) for insulin between the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems. In addition, the cross-reactivity of insulin glargine in the Lumipulse G1200 was lower than the calculated RCV (12.0%). Cross-reactivity with proinsulin was less than 1% for both systems at all concentrations tested.

Table 2. Cross-reactivity of insulin analogues in the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems.

| Concentration (pmol/L) | Detection level (cross-reactivity %) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humulin | Insulin lispro | Insulin detemir | Insulin aspart | Insulin glulisine | Insulin glargine | |||||||

| G1200 | E170 | G1200 | E170 | G1200 | E170 | G1200 | E170 | G1200 | E170 | G1200 | E170 | |

| 6,940 | > 100% | > 100% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | 0.16% | < 0.2% | 0.28% | 0.32% | 9.3% | < 0.2% |

| 694 | > 100% | > 100% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | 1.4% | 2.6% | 6.3% | < 0.2% |

| 69.4 | > 100% | > 100% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | 0.3% | 1.1% | 2.0% | < 0.2% |

| 6.94 | > 100% | > 100% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% | < 0.1% | < 0.2% |

Fig. 3. Bland–Altman plot showing differences between Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 insulin results for 29 patients treated with insulin glargine.

5. Reference interval

Sex differences were not observed, and single reference intervals for insulin and C-peptide were used. Insulin and C-peptide concentrations corresponding to the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the sample were 7.64–70.14 pmol/L and 0.17–0.85 nmol/L, respectively. The manufacturer's reference intervals for insulin and C-peptide for the Lumipulse G1200 system were 13.20–95.15 pmol/L and 0.21–0.85 nmol/L, respectively. The manufacturer's reference intervals for insulin and C-peptide for the Roche E170 system were 18.06–172.93 pmol/L and 0.37–1.47 nmol/L, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We compared the serum concentrations of insulin and C-peptide between diabetic patients under insulin treatment and healthy subjects. The imprecision of the Lumipulse G1200 was less than 5% CV for insulin and C-peptide, and the coefficients of determination for insulin and C-peptide were 0.9997 and 0.9996, respectively. In an investigation by an American Diabetes Association workgroup [8], only seven out of 10 assays had a CV less than 10.6% for insulin. The insulin and C-peptide assays by Lumipulse G1200 showed favorable results in the basic performance evaluation, including precision and linearity.

One recent study has shown commutability of insulin immunoassay results using reference materials [21]. It may be helpful to establish the basic accuracy of the calibrator using standard controls to compare different methods [8,22]. We evaluated the commutability between the Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems, using control materials and patient samples.

In the method comparison, there was a difference in absolute values of insulin and C-peptide between the two systems. Absolute values of the Lumipulse G1200 system were lower in diabetic patients as well as in healthy subjects. The source of discrepant results among the two insulin immunoassays is likely to be multifactorial, including antibody specificity, assay performance, clinical characteristics, and calibration procedures [8,21,23]. Although there was a slight difference in the absolute values of insulin and C-peptide concentrations between the two systems, it was not statistically significant (95% CI: −36.8–75.0), and the precision values were acceptable. In addition, reference intervals established by the manufacturer were lower for the Lumipulse G1200 system than for the Roche E170 system. Despite the minor differences, our data show that the Lumipulse G1200 system may be an alternative for the Roche E170 system.

The Lumipulse G1200 system showed limited cross-reactivity; we observed slight cross-reactivity with insulin glargine only. The Lumipulse G1200 system employs monoclonal antibodies, which recognize the α-chain and the C-terminus of the β-chain, regions that are modified during insulin analogue preparatio n. The modifications in insulin glargine, with glycine instead of asparagine at position A21 and two additional arginine residues at the end of the β-chain, might explain its cross-reactivity [13,26,27,28]. However, considering the concentration of insulin in patients treated with insulin glargine and the fact that cross-reactivity was lower than the RCV, the clinical impact is not likely to be significant, although at high concentrations, insulin glargine showed slight cross-reactivity with the Lumipulse G1200 system.

Previous studies showed variable cross-reactivity of insulin analogues; some assays showed high cross-reactivity with almost all analogues, while some showed cross-reactivity with almost none [10,11,12,13,24,25,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Parfitt et al [25] reported that a single amino acid change could produce significant cross-reactivity in some insulin assays, and cross-reactivity of analogues with up to three amino acid substitutions relative to human insulin, such as insulin glargine, was highly variable across assay platforms. We did not observe cross-reactivity with glargine with the Roche E170 system, probably because the dilutions were prepared using sample diluent [10,35]. A comparison of cross-reactivity of the insulin assays for insulin analogues on the basis of recent reports, including this study, is shown in Table 3 [10,11,12,13,24,29,31,32,33,36,37].

Table 3. Comparison of cross-reactivity of insulin analogs in various insulin assays.

| System | Lumipulse G1200 (Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan) | Roche E170 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) | Architect (Abbott Laboratories, IL, USA) | Immulite 2000 (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, NY, USA) | Unicel DxI Access (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) | Advia Centaur (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, NY, USA) | Cisbio International (Schering, MA, USA) | IMx (Abbott Park, IL, USA) | Coat-A-Count (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, NY, USA) | E-test TOSOH II (Tosoh Co., Tokyo, Japan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humulin | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Insulin aspart | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Insulin lispro | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Insulin glulisine | − | − | ± | − | + | − | − | Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Insulin detemir | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Insulin glargine | ± | ± | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ± |

| Reference | This study, 13 | 10,11,14,24,25,29,33 | 14,25,31,33 | 10,11,14,24,25,33 | 14,24,32,33 | 10,11,14,24,25,33 | 14 | 11,14,36 | 14,24 | 31 |

The Lumipulse G1200 and Roche E170 systems showed less than 1% cross-reactivity for C-peptide. Our results are consistent with studies reporting lower cross-reactivity with proinsulin. Previously, many insulin and C-peptide assays could not differentiate proinsulin and proinsulin intermediates from insulin and C-peptide [7,38]. However, cross-reactivity with proinsulin is generally<10% with modern assays, as proinsulin circulates at much lower concentrations than C-peptide [5]. Several assays discriminate between insulin and proinsulin [23]. This implies that interference of proinsulin does not significantly affect measurements of insulin and C-peptide in diabetic patients under insulin treatment.

In summary, as the Lumipulse G1200 system showed good precision and linearity for quantifying insulin and C-peptide, with no significant cross-reactivity with insulin analogues, it can be used for accurate measurement of intrinsic insulin concentrations in diabetic patients during insulin treatment.

Footnotes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article are reported.

References

- 1.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SY. It's still not too late to make a change: current status of glycemic control in Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38:194–196. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song SO, Song YD, Nam JY, Park KH, Yoon JH, Son KM, et al. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes mellitus in Korea through an investigation of the national registration project of type 1 diabetes for the reimbursement of glucometer strips with additional analyses using claims data. Diabetes Metab J. 2016;40:35–45. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2016.40.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(S1):S13–S22. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones AG, Hattersley AT. The clinical utility of C-peptide measurement in the care of patients with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2013;30:803–817. doi: 10.1111/dme.12159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oram RA, Patel K, Hill A, Shields B, McDonald TJ, Jones A, et al. A type 1 diabetes genetic risk score can aid discrimination between type 1 and type 2 diabetes in young adults. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:337–344. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark PM. Assays for insulin, proinsulin(s) and C-peptide. Ann Clin Biochem. 1999;36(Pt 5):541–564. doi: 10.1177/000456329903600501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcovina S, Bowsher RR, Miller WG, Staten M, Myers G, Caudill SP, et al. Standardization of insulin immunoassays: report of the American Diabetes Association Workgroup. Clin Chem. 2007;53:711–716. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.082214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones AG, Besser RE, Shields BM, McDonald TJ, Hope SV, Knight BA, et al. Assessment of endogenous insulin secretion in insulin treated diabetes predicts postprandial glucose and treatment response to prandial insulin. BMC Endocr Disord. 2012;12:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-12-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dayaldasani A, Rodriguez Espinosa M, Ocon Sanchez P, Perez Valero V. Cross-reactivity of insulin analogues with three insulin assays. Ann Clin Biochem. 2015;52:312–318. doi: 10.1177/0004563214551613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heald A, Bhattacharya B, Cooper H, Ullah A, McCulloch A, Smellie S, et al. Most commercial insulin assays fail to detect recombinant insulin analogues. Ann Clin Biochem. 2006;43:306–308. doi: 10.1258/000456306777695690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sapin R. Insulin assays: previously known and new analytical features. Clin Lab. 2003;49:113–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakahara Y, Kiya A, Uchida T, Uno J, Maeda A. Comparative study of three blood insulin measuring reagents with different measurement principles. Okayama J Med Technol. 2015;51:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nalbantoglu Elmas O, Demir K, Soylu N, Celik N, Ozkan B. Importance of insulin immunoassays in the diagnosis of factitious hypoglycemia. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2014;6:258–261. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CLSI. Evaluation of precision of quantitative measurement procedures; approved guideline. 3rd ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2014. CLSI EP05-A3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.CLSI. Evaluation of the linearity of quantitative measurement procedures: A statistical approach; approved guideline. CLSI EP06-A. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.CLSI. Method comparison and bias estimation using patient samples; approved guideline. 2nd ed. (Interim Revision) Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013. CLSI EP09-A2-IR. [Google Scholar]

- 18.CLSI. Defining, establishing, and verifying reference intervals in the clinical laboratory; approved guideline. 3rd ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2010. CLSI C28-A3c. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozturk O. Using biological variation data for reference change values in clinical laboratories. Biochem Anal Biochem. 2012;1:e106 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochocinska A, Snitko R, Czekuc-Kryskiewicz E, Kepka A, Szalecki M, Janas RM. Evaluation of the immunoradiometric and electrochemiluminescence method for the measurement of serum insulin in children. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2016;37:243–250. doi: 10.1080/15321819.2015.1126601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loh TP, Sutanto S, Khoo CM. Comparison of three routine insulin immunoassays: implications for assessment of insulin sensitivity and response. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55:e72–e75. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2016-0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chevenne D, Trivin F, Porquet D. Insulin assays and reference values. Diabetes Metab. 1999;25:459–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owen WE, Roberts WL. Cross-reactivity of three recombinant insulin analogs with five commercial insulin immunoassays. Clin Chem. 2004;50:257–259. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.026625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parfitt C, Church D, Armston A, Couchman L, Evans C, Wark G, et al. Commercial insulin immunoassays fail to detect commonly prescribed insulin analogues. Clin Biochem. 2015;48:1354–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch IB. Insulin analogues. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:174–183. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vajo Z, Duckworth WC. Genetically engineered insulin analogs: diabetes in the new millenium. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim S, Yun YM, Hur M, Moon HW. Unusually elevated serum insulin level in a diabetic patient during recombinant insulin therapy. Lab Med Online. 2013;3:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S, Yun YM, Hur M, Moon HW, Kim JQ. The effects of anti-insulin antibodies and cross-reactivity with human recombinant insulin analogues in the E170 insulin immunometric assay. Korean J Lab Med. 2011;31:22–29. doi: 10.3343/kjlm.2011.31.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sapin R, Le Galudec V, Gasser F, Pinget M, Grucker D. Elecsys insulin assay: free insulin determination and the absence of cross-reactivity with insulin lispro. Clin Chem. 2001;47:602–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriyama M, Hayashi N, Ohyabu C, Mukai M, Kawano S, Kumagai S. Performance evaluation and cross-reactivity from insulin analogs with the ARCHITECT insulin assay. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1423–1426. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.065995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glenn C, Armston A. Cross-reactivity of 12 recombinant insulin preparations in the Beckman Unicel DxI 800 insulin assay. Ann Clin Biochem. 2010;47:264–266. doi: 10.1258/acb.2010.010002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalathil S, Napier C, Pattman SJ, Wark G, Abouglila K, James RA. Variable characteristics with insulin assays. Pract Diabetes. 2013;30:118–120. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vieira JG, Tachibana TT, Ferrer CM, Reis AF. Cross-reactivity of new insulin analogs in insulin assays. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;51:504–505. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302007000300022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agin A, Jeandidier N, Gasser F, Grucker D, Sapin R. Glargine blood biotransformation: in vitro appraisal with human insulin immunoassay. Diabetes Metab. 2007;33:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song D, Davidson J. Cross-reactivity of Actrapid and three insulin analogues in the Abbott IMx insulin immunoassay. Ann Clin Biochem. 2007;44:197–198. doi: 10.1258/000456307780118109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neal JM, Han W. Insulin immunoassays in the detection of insulin analogues in factitious hypoglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:1006–1010. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.8.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer JP, Fleming GA, Greenbaum CJ, Herold KC, Jansa LD, Kolb H, et al. C-peptide is the appropriate outcome measure for type 1 diabetes clinical trials to preserve beta-cell function: report of an ADA workshop, 21-22 October 2001. Diabetes. 2004;53:250–264. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]