Abstract

Background

The increasing morbidity and mortality rates associated with Acinetobacter baumannii are due to the emergence of drug resistance and the limited treatment options. We compared characteristics of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CR-AB) clinical isolates recovered from patients with and without prior colistin treatment. We assessed whether prior colistin treatment affects the resistance mechanism of CR-AB isolates, mortality rates, and clinical characteristics. Additionally, a proper method for identifying CR-AB was determined.

Methods

We collected 36 non-duplicate CR-AB clinical isolates resistant to colistin. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, Sanger sequencing analysis, molecular typing, lipid A structure analysis, and in vitro synergy testing were performed. Eleven colistin-susceptible AB isolates were used as controls.

Results

Despite no differences in clinical characteristics between patients with and without prior colistin treatment, resistance-causing genetic mutations were more frequent in isolates from colistin-treated patients. Distinct mutations were overlooked via the Sanger sequencing method, perhaps because of a masking effect by the colistin-susceptible AB subpopulation of CR-AB isolates lacking genetic mutations. However, modified lipid A analysis revealed colistin resistance peaks, despite the population heterogeneity, and peak levels were significantly different between the groups.

Conclusions

Although prior colistin use did not induce clinical or susceptibility differences, we demonstrated that identification of CR-AB by sequencing is insufficient. We propose that population heterogeneity has a masking effect, especially in colistin non-treated patients; therefore, accurate testing methods reflecting physiological alterations of the bacteria, such as phosphoethanolamine-modified lipid A identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight, should be employed.

Keywords: Colistin, Population heterogeneity, Acinetobacter baumannii, Resistance, Lipid A analysis, Pathogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii (AB) has become associated with increasing morbidity and mortality rates in hospitals in the last two decades, owing to the emergence of drug resistance and limited treatment options [1,2,3,4]. Recently, an increase in carbapenem resistance among AB strains has been reported [5,6]. These carbapenem-resistant AB strains also frequently display resistance to other antibiotics, consequently posing an eminent clinical threat. Thus, interest in “old” antibiotics has been rekindled [7,8].

Colistin, introduced in the 1950s to treat infections caused by gram-negative bacteria (GNB), exerts bactericidal activity by displacing the membrane-stabilizing calcium and magnesium ions and targets the polyanionic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) components [9,10]. However, because it induced nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity, it was replaced by safer antimicrobial agents (e.g., aminoglycosides) [11,12]. Despite these potential side effects, worldwide dissemination of extensively drug-resistant GNB (XDR-GNB) has rekindled the usage of this drug in clinical settings as a last-resort treatment.

The clinical use of colistin for XDR-GNB infections has led to the development of colistin resistance (CR) in GNB species [13,14,15], and reports on the occurrence of colistin-resistant AB (CR-AB) are increasing globally [2]. Previous in vivo studies have demonstrated that CR in AB is mediated by a complete loss of LPS production through mutations in LPS-producing genes (lpxA, lpxC, lpxD, and lpsB) [16,17] or by modification of lipid A components of LPS through mutations in pmrA and pmrB genes. These genes regulate the expression of the downstream target pmrC, which encodes an inner membrane phosphoethanolamine (PE) transferase modifying the outer membrane lipid A [18,19]. Recently, the emergence of a plasmid-mediated mobile CR gene, mcr-1, in Enterobacteriaceae has been reported [20].

Most CR-AB clinical strains are reported to acquire resistance by in vivo selection during colistin treatment [21]; however, clonal spreading of CR-AB strains causing infections or colonization in patients without colistin treatment history has also been reported recently [1]. Both in vitro and in vivo models have shown that mutations in the PmrAB system lead to decreased fitness and virulence compared with that of colistin-susceptible (CS) parental strains [22,23,24]. However, these studies evaluated serially obtained CR isolates and their parental CS strains only and thus did not consider the characteristics of different clinical CR-AB isolates obtained from different patients with and without history of colistin administration [23,24,25,26].

We compared CR-AB isolates recovered from patients with and without prior colistin treatment to assess whether prior colistin treatment affects CR in CR-AB isolates, patient demographics, mortality rates, or genetic mutations. Additionally, mortality rate was assessed to determine clinical characteristics.

METHODS

1. Bacterial isolates

In total, 36 non-duplicate AB clinical isolates resistant to both carbapenems and colistin were collected from a tertiary care hospital in Seoul, Korea, from April 2012 to December 2014. At the time of sample collection, 18 patients had received previous colistin treatment (Group CT), and the rest had not (Group non-CT). For comparison, AB isolates (N=11) that were resistant to carbapenems but susceptible to colistin were also studied. Bacterial species were identified by partial rpoB gene sequences and PCR detection of blaOXA-51-like. Patient data, including acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE II) score, use of colistin treatment, and 30-day mortality from the day of AB recovery, were examined retrospectively using electronic medical records. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify risk factors associated with 30-day mortality from the day of CR-AB recovery. This project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea (4-2017-0758).

2. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The susceptibility of the isolates to colistin, meropenem, imipenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftazidime, cefepime, gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was determined by the disk diffusion method following the CLSI guidelines [27]. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of meropenem and imipenem were determined by using Etest (bioMérieux, Inc., Durham, NC, USA). Colistin MIC was determined by the broth microdilution method, following recommendations of the Joint CLSI-EUCAST Polymyxin Breakpoints Working Group [28]. Synergistic effects of drug combinations of colistin (32–4,096 µg/mL) either with meropenem (4–256 µg/mL) or with rifampicin (0.25–32 µg/mL) were evaluated by the checkerboard method [29] in microtiter plates. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index of each drug combination was determined by dividing the MIC of each drug when used in combination by the MIC of each drug when used alone. The effect of a drug combination was determined by the FIC index: ≤0.5, a synergistic effect; 0.5–4.0, neutrality; and >4.0 an antagonistic effect.

3. PCR analysis of drug-resistant genes

A series of PCR experiments (primer information available upon request) were conducted to detect the OXA carbapenemase genes blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-24-like, blaOXA-48-like, and blaOXA-58-like [30]; the metallo-β-lactamase genes blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaNDM; and the serine carbapenemase genes blaGES and blaKPC [31]. The presence of ISAba1 upstream from the blaOXA-51-like gene was detected by PCR [32].

4. Genomic analysis of genes associated with colistin resistance

Genes associated with CR in AB (pmrA, pmrB, pmrC, lpxA, lpxC, lpxD, and lpsB) were analyzed by Sanger sequencing [17,33]. The AB ATCC 17978 strain and 10 randomly selected colistin-susceptible AB (CS-AB) isolates were used as controls to distinguish CR-inducing mutations from polymorphisms. The mcr-1 gene was also identified by PCR [20].

5. Analysis of lipid A structure

Lipopolysaccharides and lipid A components were extracted from whole bacterial cells using Tri-reagent and mild acid hydrolysis, and were subjected to negative-ion matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Leipzig, Germany) in negative reflection mode. For comparison, three randomly selected CS-AB isolates were used as controls.

6. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was conducted with SmaI-digested genomic DNA extracted from the AB clinical isolates using a CHEF-DRII device (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). PFGE band patterns were analyzed with Molecular Analyst Fingerprinting Software Ver. 3.2 (Bio-Rad). Genetic relatedness of PFGE profiles was interpreted using the criteria of Tenover et al [34].

7. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST)

MLST experiments were performed following the Bartual scheme [13]. Sequences of seven housekeeping genes (cpn60, gdhB, gltA, gpi, gyrB, recA, and rpoD) were used to determine the sequence types (STs) of the AB clinical isolates. Each ST number was assigned by comparing the allele sequences with those in MLST databases (http://pubmlst.org/abaumannii). Clonal complex (CC) was defined as a group of STs that shared five or more of seven alleles and was determined by eBURSTv.3 (http://eburst.mlst.net).

8. Statistical analysis

All variables were evaluated for Gaussian distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences were tested with the Fisher exact test for categorical data and with the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data. Univariate and multivariate analyses were carried out using logistic regression to investigate the association between CR, mortality rate, and potential covariates. The presence of variance inflation factors was examined for all parameters of the multiple regression model. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R (Version 0.99.893, R Studio, Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

RESULTS

1. Clinical characteristics of patients

The characteristics of patients infected or colonized by CR-AB are presented in Table 1. To determine whether prior colistin treatment had any relevant effect on patient outcome, Groups CT and non-CT were compared.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study patients.

| Variables | All patients (N=36) | CT | Non-CT | P | Univariate an | alysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=18) | (N=18) | OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| Age (yr) | 53.9 ± 27.4 | 66.5 (16.0–72.0) | 67.5 (44.0–71.0) | 0.624 | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | 0.626 |

| Male sex* | 21 (58.3%) | 12 (66.7%) | 9 (50.0%) | 0.499 | 2 (0.53–8.03) | 0.313 |

| Infection type* | 0.472 | |||||

| Bloodstream infection | 7 (19.4%) | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0.7 (0.12–3.73) | 0.674 | |

| Respiratory infection | 25 (69.4%) | 11 (61.1%) | 14 (77.8%) | 2.23 (0.53–10.41) | 0.283 | |

| Other | 4 (11.1%) | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (5.6%) | |||

| Ventilator care* | 28 (77.8%) | 15 (83.3%) | 13 (72.2%) | 0.688 | 1.92 (0.39–10.89) | 0.427 |

| History of colistin treatment | 18 (50.0%) | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Treatment duration (day) | 18.9 ± 13.1 | 18.0 (7.0–29.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | |||

| 30-day mortality | 13 (36.1%) | 7 (38.9%) | 6 (33.3%) | 0.999 | 1.27 (0.32–5.12) | 0.729 |

| APACHE II | 12.6 ± 4.2 | 13.2 ± 4.2 | 11.9 ± 4.3 | 0.92 (0.78–1.08) | 0.339 | |

| ICU stay during isolate recovery | 29 (80.6%) | 14 (38.9%) | 15 (41.7%) | |||

| ICU admission history* | 35 (97.2%) | 17 (94.4%) | 18 (100.0%) | 0.999 |

Data are presented as number (%), mean±SD for parametric variables or median [1st quartile–3rd quartile] for non-parametric variables.

*Categorical variables included in logistic regression.

Abbreviations: CT, colistin treatment; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

To determine the characteristics associated with higher survival rates, the “within 30-days deceased group” (13/36) was compared with the “alive group” (23/36) (Table 2). Only bloodstream infection and APACHE II scores significantly differed between groups.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for 30-day mortality.

| Variables | Death (N=13) | Survival (N=23) | P | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | ||||

| Age (yr) | 66.0 (4.0–71.0) | 67.0 (50.5–71.5) | 0.419 | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 0.142 | ||

| Male sex* | 5 (38.5%) | 10 (43.5%) | 0.999 | 1.23 (0.31–5.17) | 0.770 | ||

| Infection type* | 0.005 | ||||||

| Bloodstream infection | 6 (46.2%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.05 (0–0.38) | 0.012 | 0.02 (0–0.22) | 0.011 | |

| Respiratory infection | 7 (53.8%) | 18 (78.3%) | 3.09 (0.72–14.23) | 0.134 | |||

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (17.4%) | |||||

| Ventilator care* | 13 (100.0%) | 15 (65.2%) | 0.046 | NA | 0.994 | ||

| History of colistin treatment* | 7 (53.8%) | 11 (47.8%) | 0.999 | 1.27 (0.32–5.12) | 0.729 | ||

| Treatment duration (day) | 21.7 ± 18.5 | 17.2 ± 8.9 | 0.562 | 0.97 (0.89–1.05) | 0.471 | ||

| APACHE II | 14.6 ± 4.3 | 11.4 ± 3.7 | 0.025 | 0.81 (0.65–0.97) | 0.035 | 0.73 (0.53–0.92) | 0.019 |

| ICU admission history* | 13 (100.0%) | 22 (95.7%) | 0.999 | NA | 0.995 | ||

| MLST* | 0.604 | NA | 0.995 | ||||

| ST191 | 13 (100.0%) | 20 (87.0%) | |||||

| ST357 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | |||||

| ST858 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | |||||

| ST872 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | |||||

Data are presented as N (%), mean±SD for parametric variables, or median [1st quartile–3rd quartile] for non-parametric variables. Bold values are statistically significant (P<0.05).

*Categorical variables included in logistic regression.

All colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates were within clonal cluster 92.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ICU, intensive care unit; MLST, Multilocus sequence typing.

2. Strain typing

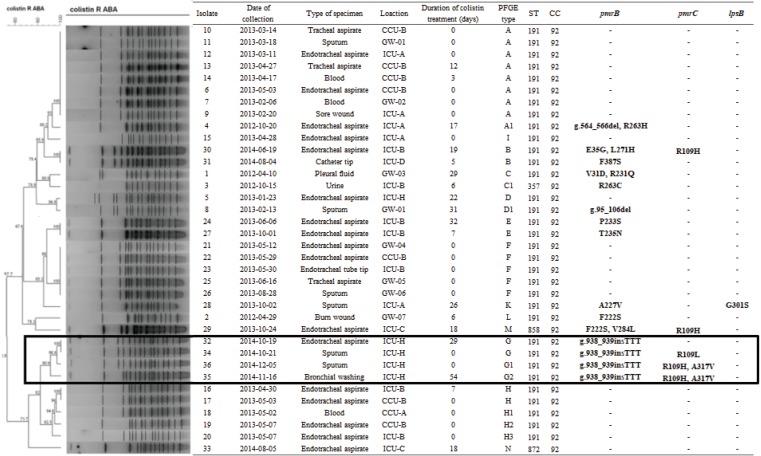

MLST showed that all CR-AB isolates belonged to CC92. Among these, 91.7% (33/36) were identified as ST191 (Fig. 1). All isolates from Group non-CT belonged to ST191, whereas the three non-ST191 isolates were retrieved from Group CT. The 36 CR-AB isolates were assigned to 13 PFGE types (pulsotypes A to N) on the basis of banding patterns. With the exception of pulsotype A1, isolates of pulsotypes A, F, and H did not show any CR-related genetic mutations, and the majority (16/18) of the host patients belonged to Group non-CT. However, isolates of pulsotypes B, C, E, and G showed genetic mutations, and most (8/10) of the host patients belonged to Group CT.

Fig. 1. Dendrogram showing cluster analysis of SmaI-digested pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns from colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. Mutations from genomic analysis of genes associated with colistin resistance are listed on the right in bold font. Note that CR-AB32, 34, 35, and 36 had the same mutation in the pmrB gene (insertion TTT at g.938_939) and were isolated from a single location (ICU-H) within 47 days (highlighted by a black rectangle).

ABA, Acinetobacter baumannii; CC, clonal complex; CCU, coronary care unit; GW, general ward; ICU, intensive care unit; PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; ST, sequence type; CS-AB, colistin-susceptible Acinetobacter baumannii; CR-AB, colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

3. PCR analysis and antimicrobial susceptibility

Only the blaOXA-23-like carbapenemase gene was found in all CR-AB isolates. No other carbapenemase genes were detected by PCR. ISAba1, located upstream from the blaOXA-51-like gene, was not detected. All CR-AB isolates were resistant to more than three antimicrobial classes by a disk diffusion susceptibility test (data not shown). All colistin MICs determined by the broth microdilution method were >128 µg/mL.

4. Mutations in genes associated with colistin resistance

All isolates with genetic mutations had mutated pmrB gene, and pmrB gene was the most frequently mutated (16/36, 44.4%). Genetic mutations were more frequently observed in isolates from Group CT than in those from Group non-CT patients (72.2% [13/18] and 11.1% [2/18], respectively, P≤0.001). CR-AB 32, 34, 35, and 36 had the same mutation in pmrB (g.938_939insTTT) and belonged to the same strain type according to both PFGE (pulsotype G) and MLST (ST191). These patients stayed in the same isolated location (ICU-H) for more than 47 days. Based on the available microbiological and clinical information, we concluded that these isolates were of the same strain, and clonal spread was revealed. Interestingly, with the exception of two isolates (CR-AB35 and 37), no genetic mutations were detected in isolates from Group non-CT.

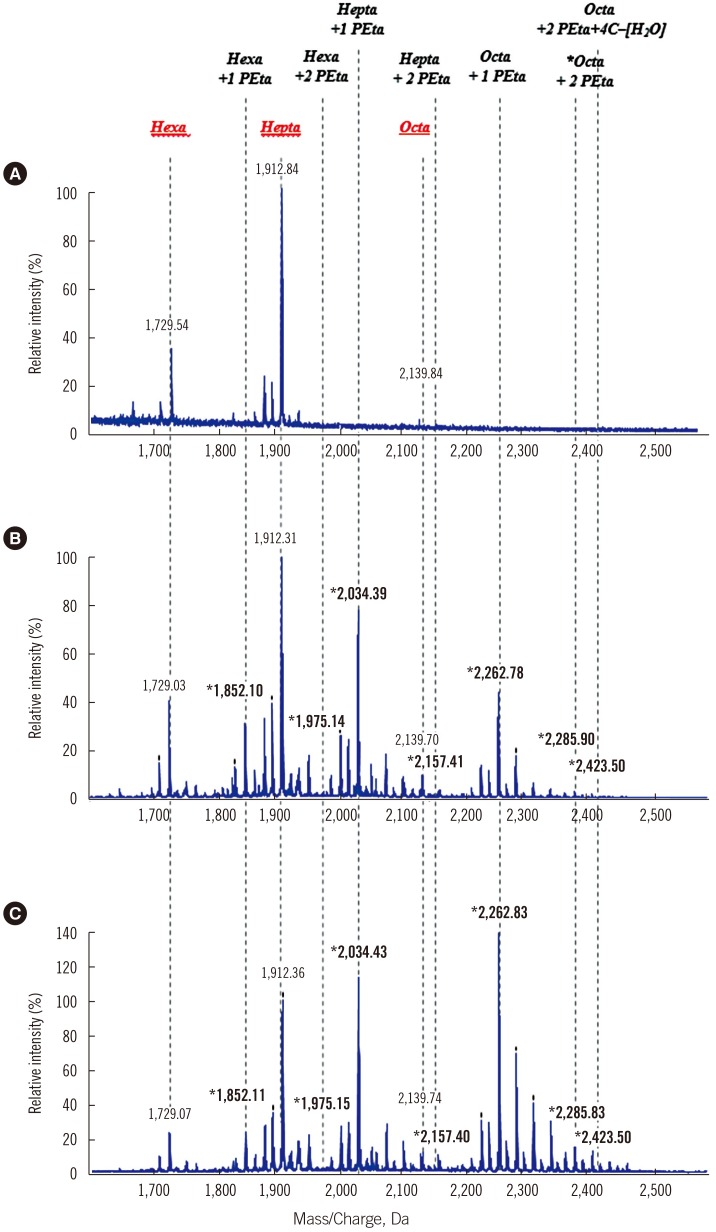

5. Lipid A structure

Lipid A MALDI-TOF mass spectra of CR-AB isolates showed distinct profiles (Fig. 2). Common intensity peaks at m/z 1729, 1912, and 2139 were found in both CS-AB and CR-AB, indicating normal hexa-, hepta-, and octa-acylated lipid A, whereas in some isolates, the hexa- and octa-acylated lipid A peaks were completely changed to phosphoethanolaminated lipid A (hexa-acylated: 1/36, octa-acylated: 9/36). In each isolate, intensities of other lipid A components were compared with that of the hepta-acylated lipid A peak (Table 3), which was set as 100% because some hexa- and octa-acylated peaks were completely lost, and therefore were not suitable as reference peaks.

Fig. 2. Mass spectrometry of lipid A extracted from colistin-susceptible isolates and CR-AB. (A) ATCC 17978, wild type CS-AB. (B) CR-AB18, Group non-CT. (C) CR-AB14, Group CT. The mass (m/z) of peaks only detected in CR-AB strains is indicated in bold.

Abbreviations: Hexa, hexa-acylated lipid A; Hepta, hepta-acylated lipid A; Octa, octa-acylated lipid A; PE, phosphoethanolamine; C, carbon; CS-AB, colistin-susceptible Acinetobacter baumannii; CR-AB, colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

Table 3. Genetic characteristics and lipid A composition of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from patients with and without colistin treatment.

| Colistin-susceptible A. baumannii (N=3)† | Colistin-resistant A. baumannii (N=36) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT (N=18) | Non-CT (N=18) | |||

| Relative percentage of each lipid A component peak (%)* | ||||

| Hexa | 39.8 (29.8–40.6) | 13.3 (2.1–49.7) | 24.7 (0–58.1) | 0.021 |

| Hexa+1-PE | 0 (0–1.0) | 21.2 (8.3–146.9) | 24.3 (2.1–78.5) | 0.448 |

| Hexa+2-PE | 0 (0–0) | 2.1 (0–43.3) | 0 (0–3.7) | 0.008 |

| Hepta | 100 (100–100) | 100 (100–100) | 100 (100–100) | - |

| Hepta+1-PE | 0 (0–1.0) | 143.5 (63.5–353.4) | 108.6 (62.2–204.7) | 0.018 |

| Hepta+2-PE | 0 (0–0) | 29.4 (0–71.1) | 1.9 (0–31.6) | < 0.001 |

| Octa | 9.1 (2.2–12.9) | 5.5 (0–11.6) | 6.6 (0–12.6) | 0.355 |

| Octa+1-PE | 0 (0–0) | 47.3 (15.2–137.7) | 58.9 (25.7–316.7) | 0.393 |

| Octa+2-PE | 0 (0–0) | 51.3 (0.3–220.8) | 5.8 (1.7–255.7) | 0.002 |

| Octa+2-PE+4C-H2O | 0 (0–0) | 16.3 (0–100.7) | 0 (0–58.2) | 0.001 |

| Isolates with genetic mutations, N (%) | ||||

| Overall | 0 (0%) | 13 (72.2%) | 2 (11.1%) | < 0.001 |

| pmrB | 13 (72.2%) | 2 (11.1%) | < 0.001 | |

| pmrC | 4 (22.2%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0.658 | |

| lpsB | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 | |

Bold values are statistically significant (P<0.05).

*Data represent the relative intensity (%) and their range compared with hepta-acylated lipid A, set as 100%.

†For comparison, three randomly selected colistin-susceptible Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates were used as controls.

Abbreviations: CT, colistin treatment; Hexa, hexa-acylated lipid A; Hepta, hepta-acylated lipid A; Octa, octa-acylated lipid A; PE, phosphoethanolamine; C, carbon.

Peak intensity was significantly higher at two phosphoethanolamine (PE)-modified hexa-, hepta- and octa-acylated lipid A (P=0.008, <0.001, and 0.002, respectively) in isolates from Group CT than in those from Group non-CT. Furthermore, original hexa-acylated lipid A intensity peaks were significantly lower (P=0.021), and two PE-modified octa-acylated lipid A with 4C-H2O was significantly higher in isolates from Group CT (P=0.01).

The lipid A composition determined by MALDI-TOF M/S divided the CR-AB strains into strains harboring pmrB mutation and those having normal pmrB (Table 4). When lipid A peaks were grouped and analyzed according to the number of substitutions occurring in pmrB, pmrC, and lpsB genes, only the octa-acylated lipid A peak and its PE-modified forms were statistically different.

Table 4. Lipid A composition with genetic pmrB and other gene mutations of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

| Relative percentage of each lipid A component peak (%)* | Genetic mutation not detected (N = 21) | Genetic mutation detected (N = 15) | P | pmrB gene single mutation (N = 7) | pmrB gene two mutations (N = 2) | pmrB gene and other mutation (N = 6) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexa | 24.8 (18.9–37.4) | 11.3 (8.7–14.7) | < 0.001 | 15.8 (10.8–19.2) | 11.9 (10.3–13.5) | 8.7 (2.0–11.3) | 0.099 |

| Hexa+1-PE | 25.2 (20.0–32.8) | 19.2 (17.0–22.4) | 0.026 | 19.2 (17.4–22.0) | 14.7 (10.6–18.9) | 20.8 (16.7–23.5) | 0.588 |

| Hexa+2-PE | 0.0 (0.0–1.1) | 3.6 (1.1–5.6) | 0.002 | 5.0 (3.0–6.4) | 4.1 (0.7–7.4) | 0.7 (0.0–3.6) | 0.074 |

| Hepta | 21 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | - | 7 (100.0%) | 2 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 0.247 |

| Hepta+1-PE | 107.1 (84.6–127.7) | 175.9 (138.1–196.4) | < 0.001 | 175.9 (140.8–179.9) | 131.6 (118.5–144.7) | 196.4 (136.8–219.5) | 0.381 |

| Hepta+2-PE | 1.8 (0.6–4.1) | 31.6 (25.2–36.9) | < 0.001 | 31.4 (29.4–34.8) | 27.1 (22.0–32.2) | 33.9 (11.4–42.6) | 0.944 |

| Octa | 5.6 (0.0–10.0) | 6.0 (3.2–7.5) | 0.686 | 6.0 (5.1–6.7) | 3.4 (1.6–5.1) | 7.5 (0.0–8.2) | 0.479 |

| Octa+1-PE | 71.3 (44.6–85.4) | 42.8 (31.8–70.1) | 0.127 | 51.5 ± 29.4 | 19.9 ± 4.5 | 65.0 ± 27.4 | 0.458 |

| Octa+2-PE | 5.8 (3.0–13.9) | 85.3 (44.0–129.3) | < 0.001 | 55.3 (44.0–105.3) | 34.7 (31.0–38.4) | 125.8 (90.1–181.2) | 0.029 |

| Octa+2-PE+4C-H2O | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 23.9 (15.8–52.6) | < 0.001 | 21.1 (4.4–46.4) | 15.8 (15.3–16.2) | 45.5 (32.1–58.2) | 0.201 |

Data are presented as number (%), mean±SD for parametric variables or median [1st quartile–3rd quartile] for non-parametric variables. Bold values are statistically significant (P<0.05)

*Data represent the relative intensity (%) and their range compared with hepta-acylated lipid A, set as 100%.

Abbreviations: Hexa, hexa-acylated lipid A; Hepta, hepta-acylated lipid A; Octa, octa-acylated lipid A; PE, phosphoethanolamine; C, carbon.

6. In vitro synergy testing

In vitro synergistic resistance effects (ΣFIC ≤0.5) for CR-AB isolates were most frequently observed for the colistin-meropenem combination (94.4%, 34/36) followed by the colistin-rifampicin combination (83.3%, 30/36). Although the synergy testing did not show significant differences (colistin-meropenem, P=0.467; colistin-rifampicin, P=0.655), combinations of colistin with meropenem or rifampin lowered the colistin MICs by 16-fold (range, 4–128-fold) and 8-fold (range, 4–128-fold), respectively (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In our comparison of the characteristics of CR-AB clinical isolates recovered from CT and non-CT patients, no specific patient trait was found relevant to the clinical outcome. As for the mortality rate, the APACHE II score and bloodstream infections were two noteworthy markers that should be taken into consideration when managing CR-AB-infected patients. These findings were expected because the APACHE II scoring system is designed to measure disease severity in patients admitted to ICUs, and because bloodstream infections have a negative impact on patient outcome [35]. Although there were no significant differences in terms of patient characteristics, the causative CR-AB isolates presented obvious differences associated with CR, such as altered lipid A components, as indicated by MALDI-TOF M/S and genetic mutations associated with outer membrane modification.

Most of the CR-AB isolates from Group non-CT did not show any genetic mutations, whereas the revised lipid A component was characterized by shifted lipid A component peaks in MALDI-TOF M/S. Two potential hypotheses explain these unexpected results. First, the isolates may be a hetero-population composed of subpopulations of CR-AB and CS-AB lacking any evident genetic mutation, thus presenting with so-called heteroresistance [3]. Heteroresistance may be the primary stage, which in the presence of colistin, results in the proliferation of resistant subpopulations, and may prolong the treatment period or even lead to mortality [3,15,36,37]. The major subpopulation of CS-AB possibly produces erroneous colistin susceptibility data when using commercially automated systems and disk diffusion tests [3], whereas multiplication of the minor CR-AB subpopulation results in at least little growth in the presence of high concentrations of colistin by broth dilution, resulting in high MICs [3,36]. The different density of subpopulations might mask genetic mutations in CR-AB strains analyzed by Sanger sequencing. Similar findings have been demonstrated in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [38,39]. PCR-based detection was not sufficient to identify heteroresistance, because minor allele frequencies of less than 15% were below the detection threshold of the method [40]. In addition, the CS-AB population feasibly flourished owing to better fitness in a colistin-free environment compared with the CR-AB population. As a consequence, the proportion switch of the two subpopulations might have produced ambiguous results. Secondly, although less likely, a novel mechanism conferring resistance to colistin might be involved. Since this study focused on genetic mutations in known CR-associated genes, unknown mechanisms of resistance might have been missed. Future studies should conduct a complex functional whole-genome analysis.

Regardless of the population heterogeneity, CR-AB was detectable by MALDI-TOF M/S, based on distinct spectra of modified lipid A compositions. Modification of lipid A by the addition of PE to the hexa-, hepta-, and octa-acylated lipid A has been suggested as a major mechanism of CR in AB. Similarly, even though some isolates exhibited unmodified lipid A peaks in this study, CR-AB displayed shifted peaks of one or two PE additives to the three lipid A moieties. Interestingly, the relative peak levels of PE-modified compared with unmodified lipid A components were much more elevated in Group CT. Notably, the relative peak levels of the two PE modified hepta-acylated lipid A moieties clearly separated the two groups.

Most of the CR-AB isolates from both groups showed a synergistic effect of colistin upon addition of meropenem or rifampin: synergism of both combinations was observed for most isolates, without any noticeable difference between combinations or between groups. Thus, combination treatment with either meropenem or rifampin should be considered for both CT and non-CT patients.

Out study has some limitations. As its main scope was to determine characteristics of CR-AB in clinical isolates and did not entail confirmation of heteroresistance, we could not confirm heteroresistant AB. Our data were collected from a single center in Korea, so the findings may not be generalized to other institutions. The limited number of CR-AB isolates precludes definitive conclusions on heterogeneous AB populations and CR.

Our study demonstrated that although there were no differences in clinical characteristics between Groups CT and non-CT, there were pathological differences, including those involving characteristics useful in diagnosing CR-AB. Population heterogeneity masked resistance-causing genetic mutations, traditionally determined by Sanger sequencing, especially in Group non-CT; therefore, to identify CR, accurate testing methods reflecting physiological alteration of the bacteria, such as PE-modified lipid A identification by MALDI-TOF M/S, should be carried out. Since colistin heteroresistance is common in patients without prior drug treatment and can be caused by better bacterial fitness in the colistin-free environment, lipid A analysis shows clearer results for CR-AB isolates. Broth microdilution was found to accurately determine CR in AB regardless of population heterogeneity, which prevented exact susceptibility interpretation because of the subpopulations of CR-AB. Furthermore, combination treatment, specifically with meropenem and rifampicin, should be considered for the treatment of CR-AB infections.

Acknowledgments

The Research Program funded by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016ER230100#) supported this work.

Footnotes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Agodi A, Voulgari E, Barchitta M, Quattrocchi A, Bellocchi P, Poulou A, et al. Spread of a carbapenem- and colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ST2 clonal strain causing outbreaks in two Sicilian hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 2014;86:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai Y, Chai D, Wang R, Liang B, Bai N. Colistin resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii: clinical reports, mechanisms and antimicrobial strategies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1607–1615. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Rayner CR, Nation RL, Owen RJ, Spelman D, Tan KE, et al. Heteroresistance to colistin in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2946–2950. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00103-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peleg AY, Hooper DC. Hospital-acquired infections due to Gram-negative bacteria. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1804–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0904124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amudhan SM, Sekar U, Arunagiri K, Sekar B. OXA beta-lactamase-mediated carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:269–274. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.83911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans BA, Amyes SG. OXA beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:241–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00117-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karaiskos I, Galani L, Baziaka F, Giamarellou H. Intraventricular and intrathecal colistin as the last therapeutic resort for the treatment of multi-drug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventriculitis and meningitis: a literature review. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41:499–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nation RL, Li J. Colistin in the 21st century. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:535–543. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328332e672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newton BA. The properties and mode of action of the polymyxins. Bacteriol Rev. 1956;20:14–27. doi: 10.1128/br.20.1.14-27.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schindler M, Osborn MJ. Interaction of divalent cations and polymyxin B with lipopolysaccharide. Biochemistry. 1979;18:4425–4430. doi: 10.1021/bi00587a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falagas ME, Rafailidis PI, Matthaiou DK. Resistance to polymyxins: Mechanisms, frequency and treatment options. Drug Resist Updat. 2010;13:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch-Weser J, Sidel VW, Federman EB, Kanarek P, Finer DC, Eaton AE. Adverse effects of sodium colistimethate. Manifestations and specific reaction rates during 317 courses of therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1970;72:857–868. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-72-6-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meletis G, Tzampaz E, Sianou E, Tzavaras I, Sofianou D. Colistin heteroresistance in carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:946–947. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pournaras S, Ikonomidis A, Markogiannakis A, Spanakis N, Maniatis AN, Tsakris A. Characterization of clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa heterogeneously resistant to carbapenems. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:66–70. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46816-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yau W, Owen RJ, Poudyal A, Bell JM, Turnidge JD, Yu HH, et al. Colistin hetero-resistance in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates from the Western Pacific region in the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance programme. J Infect. 2009;58:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hood MI, Becker KW, Roux CM, Dunman PM, Skaar EP. Genetic determinants of intrinsic colistin tolerance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect Immun. 2013;81:542–551. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00704-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moffatt JH, Harper M, Harrison P, Hale JD, Vinogradov E, Seemann T, et al. Colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii is mediated by complete loss of lipopolysaccharide production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4971–4977. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00834-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams MD, Nickel GC, Bajaksouzian S, Lavender H, Murthy AR, Jacobs MR, et al. Resistance to colistin in Acinetobacter baumannii associated with mutations in the PmrAB two-component system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3628–3634. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00284-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee H, Hsu FF, Turk J, Groisman EA. The PmrA-regulated pmrC gene mediates phosphoethanolamine modification of lipid A and polymyxin resistance in Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4124–4133. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4124-4133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y, Bae IK, Lee H, Jeong SH, Yong D, Lee K. In vivo emergence of colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates of sequence type 357 during colistin treatment. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79:362–366. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beceiro A, Moreno A, Fernandez N, Vallejo JA, Aranda J, Adler B, et al. Biological cost of different mechanisms of colistin resistance and their impact on virulence in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:518–526. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01597-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hraiech S, Roch A, Lepidi H, Atieh T, Audoly G, Rolain JM, et al. Impaired virulence and fitness of a colistin-resistant clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii in a rat model of pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5120–5121. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00700-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López-Rojas R, McConnell MJ, Jiménez-Mejías ME, Domínguez-Herrera J, Fernández-Cuenca F, Pachón J. Colistin resistance in a clinical Acinetobacter baumannii strain appearing after colistin treatment: effect on virulence and bacterial fitness. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:4587–4589. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00543-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones CL, Singh SS, Alamneh Y, Casella LG, Ernst RK, Lesho EP, et al. In vivo fitness adaptations of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates to oxidative stress. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00598-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López-Rojas R, Domínguez-Herrera J, McConnell MJ, Docobo-Peréz F, Smani Y, Fernández-Reyes M, et al. Impaired virulence and in vivo fitness of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:545–548. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 26th ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2016. CLSI supplement M100-S26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.EUCAST. Recommendations for MIC determination of colistin (polymyxin E) as recommended by the joint CLSI-EUCAST Polymyxin Breakpoints Working Group. [Updated on Mar 2016]. http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/General_documents/Recommendations_for_MIC_determination_of_colistin_March_2016.pdf.

- 29.Orhan G, Bayram A, Zer Y, Balci I. Synergy Tests by E Test and checkerboard methods of antimicrobial combinations against Brucella melitensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:140–143. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.140-143.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodford N, Ellington MJ, Coelho JM, Turton JF, Ward ME, Brown S, et al. Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;27:351–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cicek AC, Saral A, Iraz M, Ceylan A, Duzgun AO, Peleg AY, et al. OXA- and GES-type beta-lactamases predominate in extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a Turkish University Hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:410–415. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segal H, Garny S, Elisha BG. Is IS(ABA-1) customized for Acinetobacter? FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;243:425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beceiro A, Llobet E, Aranda J, Bengoechea JA, Doumith M, Hornsey M, et al. Phosphoethanolamine modification of lipid A in colistin-resistant variants of Acinetobacter baumannii mediated by the pmrAB two-component regulatory system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3370–3379. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00079-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pittet D, Tarara D, Wenzel RP. Nosocomial bloodstream infection in critically ill patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1994;271:1598–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.20.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawley JS, Murray CK, Jorgensen JH. Colistin heteroresistance in Acinetobacter and its association with previous colistin therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:351–352. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00766-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moosavian M, Shoja S, Nashibi R, Ebrahimi N, Tabatabaiefar MA, Rostami S, et al. Post neurosurgical meningitis due to colistin heteroresistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2014;7:e12287. doi: 10.5812/jjm.12287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eilertson B, Maruri F, Blackman A, Herrera M, Samuels DC, Sterling TR. High proportion of heteroresistance in gyrA and gyrB in fluoroquinolone-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3270–3275. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02066-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pholwat S, Stroup S, Foongladda S, Houpt E. Digital PCR to detect and quantify heteroresistance in drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohlin A, Wernersson J, Engwall Y, Wiklund L, Bjork J, Nordling M. Parallel sequencing used in detection of mosaic mutations: comparison with four diagnostic DNA screening techniques. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1012–1020. doi: 10.1002/humu.20980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]