Abstract

Background

Primary central nervous system lymphoma is a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with exclusive manifestation in the central nervous system (CNS), leptomeninges, and eyes. Its incidence is 0.5 per 100 000 persons per year. Currently, no evidence-based standard of care exists.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications (2000–2017) retrieved by a selective search in PubMed.

Results

The clinical and neuroradiological presentation of primary CNS lymphoma is often nonspecific, and histopathological confirmation is obligatory. The disease, if left untreated, leads to death within weeks or months. If the patient’s general condition permits, treatment should consist of a high-dose chemotherapy based on methotrexate (HD-MTX) combined with rituximab and other cytostatic drugs that penetrate the blood–brain barrier. Long-term survival can be achieved in patients under age 70 by adding non-myeloablative consolidation chemotherapy or high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (HD-AST) to the induction therapy. Clinical trials comparing the efficacy and toxicity of these two treatment strategies are currently underway. Consolidation whole-brain radiotherapy is associated with the risk of severe neurotoxicity and should be reserved for patients who do not qualify for systemic treatment. Some 30% of patients are refractory to primary treatment, and at least 50% relapse. In patients who are still in good general condition, relapse can be managed with HD-AST. Re-exposure to conventional HD-MTX–based polychemotherapy is another option, if the initial response was durable. The 5-year survival rate of all treated patients is 31%, according to registry data.

Conclusion

Current recommendations for the treatment of primary CNS lymphoma are based on only a small number of prospective clinical trials. Patients with this disease should be treated by interdisciplinary teams in experienced centers, and preferably as part of a controlled trial.

Primary central nervous system lymphomas (PCNSL) are aggressive brain tumors. They are a form of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) with exclusive manifestation in the brain, leptomeninges, and spinal cord. Ocular involvement (vitreoretinal lymphoma) is seen in 10% of patients and leptomeningeal tumor spread is found in about 15% of patients (1– 3). Only highly proliferative, diffuse large B-cell lymphomas without systemic manifestation are categorized as PCNSL according to the most recent WHO classification (4).

PCNSLs account for 2% to 4% of all primary brain tumors (5). The incidence is about 0.5/100 000 persons per year, with over-65-year-olds being more commonly affected and a rising incidence in this age group. Men are more commonly affected than women (sex ratio 1.35 : 1) (6, 7). Immunosuppression is one of the risk factors for PCNSL; in this situation, PCNSL is typically associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) (8).

Even though the prognosis of PCNSL has significantly improved over the last decades (median survival improved from 2.5 to 26 months) (7) and intensive treatments can achieve long-term remission in young patients, no evidence-based standard of care exists. Treatment recommendations are based on retrospective case series and few larger prospective studies. Among older patients, highly effective treatments are often associated with serious adverse events and the prognosis in this age group is significantly less favorable with median survival rates between 7 to 19 months, regardless of treatment (7, 9).

PCNSL is a rare cancer that is easily overlooked in the differential diagnosis and that is managed differently from other brain tumors. We therefore set out to provide a summary of the currently available evidence on its diagnosis and treatment.

Methods

We performed a PubMed search for the years 2000–2017, using the search algorithm: “primary central nervous system lymphoma“ AND/OR “pcnsl“; filters activated: “meta-analysis“, “systematic reviews“, “randomized controlled trial“, “guideline“, “clinical trial“, “abstract“, “humans“, “English“, “German“. The search yielded 1175 results. After evaluating the abstracts (LB), 85 high-quality sources, including some older articles, were selected as relevant for our paper and included in our analysis on a consensus basis with the other authors.

Clinical signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of PCNSL are nonspecific and rapidly progressive. Frequently (50–70% of cases), patients present with personality changes and cognitive impairments; in addition, 50% of patients experience focal neurological deficits. Signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure are less commonly observed at the time of diagnosis. These include headache, nausea, decreased alertness, seizures or, in case of vitreoretinal involvement, ocular symptoms (vitreous floaters, visual impairment).

Although leptomeningeal involvement is usually asymptomatic, it may trigger headache, neck or back pain and radicular symptoms (1, 8).

Imaging studies

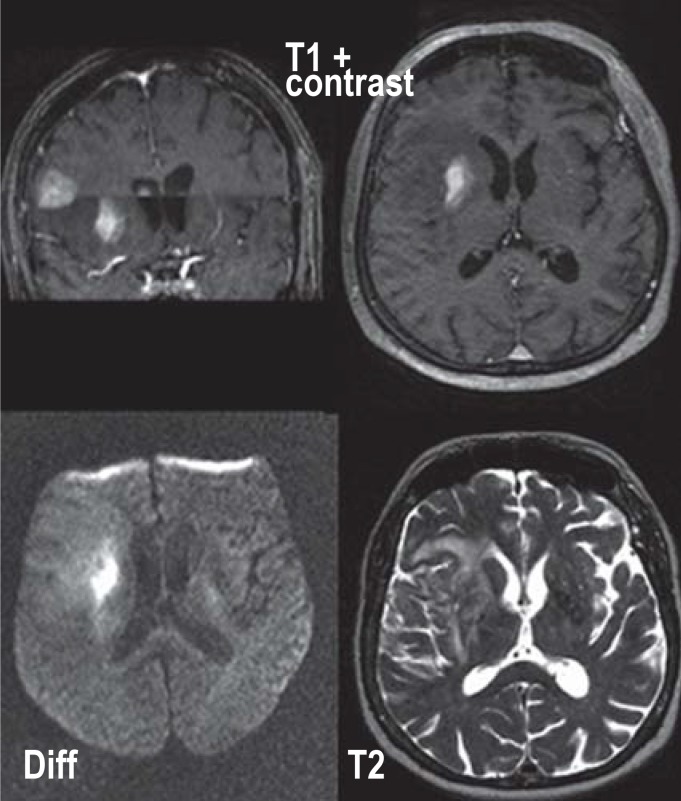

Contrast-enhanced cranial magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) is the most useful imaging modality (2, 10); however, nonspecific findings are not uncommon. It reveals unifocal or, in 35% of patients, multifocal, mainly supratentorial periventricular space-occupying lesions. Contrast enhancement is intense and generally homogeneous, but in 6% to 17% of patients inhomogeneous or missing (<2%) (10, 11). Typically, PCNSLs show significant diffusion restriction due to cell density and appear hypointense on T2-weighted imaging and iso-/hypointense on T1-weighted imaging (10, 11) (figure 1). Regions of the brain with normal imaging morphology are usually also involved (12).

Figure 1.

Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) of a patient with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL). A cMRI scan of this 61-year-old female patient was obtained because of personality changes rapidly progressing over several weeks, dysarthria, and unsteady gait. It revealed a homogeneously contrast-enhancing PCNSL (T1 with contrast) with diffusion abnormality in the diffusion-weighted (DWI) sequences and hyperintensity in T2-weighted sequences

Differential diagnosis

Imaging alone does not allow reliable discrimination from other malignant brain tumors (CNS metastasis, malignant glioma) or space-occupying inflammatory lesions (multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, vasculitis), more rarely of infectious nature (abscess, opportunistic CNS infections and toxoplasma encephalitis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy) (3, 10); therefore, PCNSL should always be included in the differential diagnosis of space-occupying lesions of the brain. Regression of clinical and imaging findings of variable duration (usually weeks to months, rarely longer) is observed under steroid treatment in 40% to 80% of cases (13, 14). The histological picture is dominated by nonspecific inflammatory and reactive changes, while tumor cells are missing (3, 15). Therefore, in patients with suspected PCNSL, steroid treatment should be avoided before biopsies for histology have been taken.

Confirmation of diagnosis

Histopathological confirmation of the diagnosis is essential and should be sought without delay, given the aggressive course of the disease (2). Confirmation is typically achieved by stereotactic serial biopsies which are associated with a low peri-interventional risk for the patient (16). In the case of leptomeningeal or ocular involvement, lymphoma cells can only rarely be detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or in the vitreous body aspirate using (immuno)cytological, flow cytometric or molecular biology methods. However, the latter does not allow definite classification of the lymphoma according to the WHO criteria which require immunohistochemistry for confirmation (4). Currently, diagnostic biomarkers (proteins, RNA, DNA) in the cerebrospinal fluid do not play an established role in clinical routine (17).

In case steroid treatment was started before histology samples were obtained, the medication should be tapered off as soon as possible and then biopsies should be taken, because the diagnosis can only be established in 50% to 85% of patients under steroid treatment (15, 18). However, in case of persisting contrast enhancement and a rapidly progressive clinical course or threat to the patient’s life, the biopsy should not necessarily be delayed. In case of inconclusive findings, imaging follow-ups should be performed at close intervals to ensure that patients showing signs of progression undergo a re-biopsy (2).

Diagnosis

If a PCNSL is diagnosed, it is recommended to perform a standardized diagnostic evaluation (figure 1) (19). In addition to spinal tap and ophthalmological examination, patients should undergo whole-body computed tomography (CT), or positron emission tomography CT (PET-CT), to rule out any systemic manifestation which is found in 10% of patients with cerebral lymphoma (20).

Additionally, the guidelines recommend a bone marrow aspiration to rule out bone marrow involvement, even though it does not change the treatment approach and may be dispensable (21).

Since more than 80% of patients with isolated vitreoretinal lymphoma develop CNS involvement over the course of the disease, cMRI and spinal tap should always be performed. In all patients, clinical chemistry testing (liver and kidney function tests), HIV testing, and hepatitis serology should be undertaken (19).

Histopathology and molecular pathophysiology

PCNSLs are mature B-cell lymphomas characterized by the expression of pan B-cell markers (CD20 and CD79a) (figure 2). Typically, they have a high proliferation rate (Ki-67 proliferative index >70%). The tumor cells express germinal center markers, predominantly BCL6 and MUM1/IRF4, but no plasma cell markers (CD38, CD138). They show light-chain restriction and express IgM, but not IgG (22). Frequently, B-cell receptor, Toll-like receptor and NF-?B signaling pathways are activated by changes in regulating genes (23– 25), stimulating the proliferation of lymphoma cells and preventing their apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic algorithm for suspected primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL).

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient;

cMRI, cranial magnetic resonance imaging;

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; Echo, transthoracic echocardiography; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Scale;

IELSG, International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase;

PET, positron emission tomography; PCNSL, primary CNS lymphoma; T1, T1-weighted sequence; T2, T2-weighted sequence;

(adapted from Ferreri et al. 2011 [e47])

Prognosis

PCNSLs are highly malignant lymphomas with a median survival of weeks to months if treatment is only symptomatic; however, with anticancer therapy 5-year survival is 31% (6). Old age and poor clinical performance status have the strongest negative impact on prognosis; besides these, increased LDH levels, elevated CSF protein levels, and involvement of deeper brain regions are summarized in the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG) score (figure 2) and associated with a poorer prognosis. In low-risk patients, the 2-year survival is 80%, in moderate-risk patients 48%, and in high-risk patients only 15% (26).

Management

Available study data

PCNSL is sensitive to radiation and chemotherapy. Due to the low incidence of PCNSL, it is challenging to conduct large randomized studies. The current treatment recommendations are based on a few prospective treatment studies (Figure 2 and 3, Table). Given the heterogeneity of these studies, the small sample sizes, and the different endpoints, these studies are difficult to compare.

Figure 3.

Therapeutic algorithm for histologically confirmed primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL)

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Scale; HD-ASCT, high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation; HD-MTX, high-dose methotrexate (=3 g/m² body surface area over 4 hours).

* if in excellent general condition

Table. Studies on the first-line treatment of primary CNS lymphoma.

| Reference | N° |

Med. age (y) |

Treatment protocol (induction → intensification / consolidation) |

ORR (%) |

Med. PFS (Mo) |

Med. OS (Mo) |

|

| Conventional chemotherapy all age groups, N >40 | |||||||

| (e9) (e10)*1 |

65 | 62 | HD-MTX, vincristine, ifosfamide, cyclophosphamide → AraC/vindesine → MTX + AraC icv |

71 | 21 (TTP) | 54 | |

| 30 (≤60 y) |

52 | 64*1 | >80*1 | ||||

| 35 (>60 y) |

30*1 | 34*1 | |||||

| (e8) | 44 | 61 | Ritux, HD-MTX, TMZ → etoposide, AraC | 77 | 29 | > 59 | |

| (e43) | 39 (≤65 y) |

55 | Ritux, HD-MTX, ifosfamide, cyclophosphamide → AraC, Vindesin → liposomal AraC isp |

70 | 10 (DoR) |

> 22 | |

| 27 (>66 y) |

70 | Ritux, HD-MTX, TMZ → AraC, vindesine → lipsomal AraC isp Oral maintenance: TMZ for 12 months |

81 | >22 (DoR) |

>22 | ||

| Chemotherapy in older patients (>60 y), N >40 | |||||||

| (e6) | 50 | 72 | HD-MTX, procarbazine, lomustine → MTX + AraC icv |

48 | 7 | 14 | |

| (e34) | 95 | 72 | HD-MTX+ TMZ | 71 | 6 | 14 | |

| 73 | HD-MTX + procarbazine, vincristine → AraC | 82 | 10 | 31 | |||

| (e33) | 107 | 73 | R, HD-MTX, procarbazine (lomustine) Oral maintenance: procarbazine |

49 | 10 | 21 | |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy (RT), N >40 | |||||||

| (36) | 102 | 57 | HD-MTX, procarbazine, vincristine → RT | 94 | 24 | 37 | |

| (37) | 52 | 51 | HD-MTX, teniposide, carmustine, MTX icv, AraC icv → RT | 81 | NA | 46 | |

| (38) | 56 | 60 | HD-MTX, carmustine, procarbazine → RT | 61 | 10 | 12 | |

| (30) | 79 | 58 | HD-MTX → RT | 41 | 5 (FFS) | 10 | |

| 59 | HD-MTX + AraC → RT | 69 | 9 (FFS) | 31 | |||

| (e1) | 521 (318 per protocol) |

61 | HD-MTX, (ifosfamide) → AraC | 54 | 12 | 37 | |

| HD-MTX, (ifosfamide) → RT | 18 | 32 | |||||

| (40) | 52 | 60 | Ritux, HD-MTX, procarbazine, vincristine → AraC + drRT | 95 | 92 | >70 | |

| (39) | 53 | 57 | R, HD-MTX, TMZ → drRT Oral maintenance: TMZ for 11 months |

85 | 64 | 90 | |

| High-dose myeloablative therapy + autologous stem cell transplantation (HD-ASCT) ± RT, N ≥30 | |||||||

| (e12) (e44)*1 | 30 | 54 | HD-MTX, AraC, TT → HD-ASCT (BCNU, TT) + RT | 92 | NS | >64 104*1 |

|

| (e14) | 32 | 57 | HD-MTX, procarbazine, vincristine → HD-ASCT (busulfan, TT, cyclophosphamide) |

96 | not reached >84 |

>84 | |

| (e12) | 79 | 56 | R, HD-MTX → AraC, TT→ HD-ASCT (BCNU, TT), RT (n = 10, only if no CR after induction) |

80 | 74 | >84 | |

| (33) (34) | 75 | 58 | MTX, AraC*2 | HD-ASCT (BCNU, TT)*3 (n = 58) |

CR: 93 | 2y PFS: 75% |

2y OS 85% |

| 69 | 57 | R, HD-MTX, AraC*2 | RT*3 (n = 55) |

CR: 95 | 2y PFS: 76% |

2y OS: 71% |

|

| 75 | 57 | R, HD-MTX, AraC, TT*2 | |||||

AraC, cytarabine; BCNU, carmustine; CR, complete remissions; DoR, duration of response; drRT, dose-reduced radiotherapy; FFS, failure-free survival;

HD-ASCT, high-dose myeloablative therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation; HD-MTX, high-dose methotrexate; icv, intraventricular (via intrathecal reservoir);

Ind, induction; isp, intraspinal (via lumbar spinal tap); y, years; cons, consolidation; med age, median age; med. OS, median overall survival;

Med. PFS, median progression-free survival; N, sample size; NS, not stated; NT, delayed neurotoxicity; ORR, overall response; PR, partial remission;

R, rituximab; RT, radiotherapy; TM, treatment-associated mortality; TMZ, temozolomide; TT, thiotepa; TTP, time to progression

*1 Follow-up publication with long-term data

*2 1. randomization

*3 2. randomization

Surgical resection

A subgroup analysis of the largest PCNSL study conducted so far indicated that tumor resection may improve progression-free survival in patients with single PCNSL lesions (27). However, involvement of deeper brain structures, which is a contraindication for resection, is associated with a poorer prognosis and this was not taken into account. Thus, there is no established role of resection in the management of infiltrative PCNSL (2, 28).

Pharmacotherapy

The first-line treatment for PCNSL is systemic chemotherapy. Chemotherapy regimens for the treatment of systemic lymphoma are ineffective in PCNSL as these drugs do not readily pass the blood–brain barrier. Based on the currently available data, the following treatment strategies can be recommended:

High-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX; = 3 g/m² body surface, given as a 4-hour IV infusion) is the most effective single active agent and a key component of all combination regimens (2). Outside of clinical trials and without subsequent consolidation, HD-MTX–based polychemotherapy should be administered over at least 6 cycles together with adequate supportive care (hydration, urine alkalinization, leucovorin rescue, and monitoring of MTX levels) (2).

HD-MTX monotherapy achieves complete remissions in only 30% to 40% of patients and is comparatively well tolerated (moderate toxicity in <10% of cases) (29, 30). Adverse events include renal failure, blood count abnormalities, liver function abnormalities, pneumonitis, mucositis, and, in the long term, clinically relevant leukoencephalopathy, especially in older patients (31).

Combination chemotherapies with other cytostatic agents capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier, for example high-dose cytarabine (HD-AraC), thiotepa or ifosfamide, increase the overall response rate along with increased toxicity, while treatment-associated mortality remains unchanged (30, 32).

Treatment response to HD-MTX/AraC was further improved by adding rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody, to the regimen; however, the effect was only significant if thiotepa (MATRIX protocol, [eTable 2]) was also added (overall response rate: 53% versus 74% versus 86%). Even though hematologic adverse events occurred more commonly in the intensified treatment arm, no significant differences were found with regard to the rate of serious infectious complications and treatment-associated mortality (33). However, a point of criticism is that only 54% of all patients reached the consolidation phase of the study. This was due to inadequate stem cell collection, prolonged adverse events, and neurological deterioration despite tumor regression, among others (34). The most commonly used protocols and currently recruiting studies are listed in the eSupplement and in eTable 1 and eTable 2.

eTable 2. Common treatment protocols with dosages.

| MATRIX patients up to age 65 years (65–70 years only in ECOG 0–1) | ||||

| Induction therapy | ||||

| Rituximab | 375 | mg/m² | i. v.*1 | days –5, 0 |

| Methotrexate*2 | 3.5 | g/m² | i. v. (3 h 15’)*3 | day 1 |

| Cytarabine*4 | 2 × 2 | g/m² | i. v. (1 h) | days 2, 3 |

| Thiotepa | 30 | mg/m² | i. v. (1h) | day 4 |

| 4 cycles, repeat every 3 weeks | ||||

| HD-ASCT protocol | ||||

| Rituximab | 375 | mg/m² | i. v.*1 | day –7 |

| BCNU | 400 | mg/m² | i. v. (1 h) | day –6 |

| Thiotepa | 2 × 5 | mg/kg | i. v. (2 h) | days –5, –4 |

| ASCT | day 0 | |||

| Non-myeloablative consolidation (R-DeVic) | ||||

| Rituximab | 375 | mg/m² | i. v.*1 | day 0 |

| Dexamethasone | 40 | mg | i. v. | days 1–3 |

| Etoposide (VP-16) | 100 | mg/m² | i. v. (2 h) | days 1–3 |

| Ifosfamide | 1500 | mg/m² | i. v. (2 h) | days 1–3 |

| Carboplatin | 300 | mg/m² | i. v. (1 h) | day 1 |

| 2 cycles, repeat every 3 weeks | ||||

| Freiburg ZNS-NHL protocol—for patients with primary non-Hodgkin ‧lymphomas of the CNS up to age 65 years (potentially 65–70 years, but only if ECOG 0–1 and excellent general condition) | ||||

| Induction therapy | ||||

| Rituximab | 375 | mg/m² | i. v.*1 | days 0,10 |

| Methotrexate*2 | 8 | g/m² | i. v. (4 h) | days 1,11 |

| 2 cycles, repeat on day 20 | ||||

| Cytarabine*3 | 3 | g/m² | i. v. (3 h) | days 2, 3 |

| Thiotepa | 40 | mg/m² | i. v. (1 h) | day 4 |

| 1–2 cycles, depending on response; repeat on day 21 | ||||

| HD-ASCT protocol | ||||

| BCNU | 400 | mg/m² | i. v. (1 h) | day –6 |

| Thiotepa | 2 × 5 | mg/kg | i. v. (2 h) | days –5, –4 |

| ASCT | day 0 | |||

| Bonn protocol—for patients up to age 75 years | ||||

| Cycle A | ||||

| Methotrexate*2 | 5 | g/m² | i. v. (24 h)*5 | day 1 |

| Vincristine | 2 | mg | i. v. (15 min) | day 1 |

| Ifosfamide | 800 | mg/m² | i. v. (1 h) | days 2–5 |

| Dexamethasone | 10 | mg/m² | p. o. | days 2–5 |

| Prednisolone | 2,5 | mg | i. c. v. | days 1–4 |

| Methotrexate | 3 | mg | i. c. v. | days 1–4 |

| Cytarabine | 30 | mg | i. c. v. | day 5 |

| Cycle B | ||||

| Methotrexate*2 | 5 | g/m² | i. v. (24 h)*5 | day 1 |

| Vincristine | 2 | mg | i. v. (15 min) | day 1 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 200 | mg/m² | i. v. (1 h) | days 2–5 |

| Dexamethasone | 10 | mg/m² | p. o. | days 2–5 |

| Prednisolone | 2.5 | mg | i. c. v. | days 1–4 |

| Methotrexate | 3 | mg | i. c. v. | days 1–4 |

| Cytarabine | 30 | mg | i. c. v. | day 5 |

| Cycle C | ||||

| Cytarabine | 3 | g/m² | i. v. (3 h) | days 1, 2 |

| Vindesine | 5 | mg | i. v. (15 min) | day 1 |

| Dexamethasone | 20 | mg/m² | p. o. | days 2–5 |

| Prednisolone | 2,5 | mg | i. c. v. | days 1–4 |

| Methotrexate | 3 | mg | i. c. v. | days 1–4 |

| Cytarabine | 30 | mg | i. c. v. | day 5 |

| 6 cycles, repeat day 14, cycle sequence: A1, B1, C1, A2, B2, C2 | ||||

| PRIMAIN protocol for older or fragile patients | ||||

| Induction therapy: | ||||

| Rituximab | 375 | mg/m² | Inf.*4 | days 1, 15, 29 |

| Methotrexate*2 | 3,0 | g/m² | Inf. (4 h) | days 2, 16, 30 |

| Procarbazine | 60 | mg/m² | p. o. | days 1–10 |

| 6 cycles, repeat day 28 | ||||

| Maintenance therapy: | ||||

| Procarbazine | 100 | mg/m² | p. o. | days 1–5 |

| 6 cycles, repeat day 28 | ||||

*1 Rituximab: Rituximab: protracted infusion on initial administration 1st hour 50 mg/h, 2nd hour 100 gl/h and 3rd hour 150–250 mg/h

*2 HD-MTX: This treatment requires regular measuring of MTX levels and leucovorin rescue as well as a corresponding adjunctive therapy and emergency treatment

*3 0.5 g/m² in 15 min + 3 g/m² over 3 h

*4 Conjunctivitis prophylaxis: steroid-containing eye drops

*5 0.5 g/m² in 30 min. + 4.5 g/m² over 23.5 h

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status; HD-ASCT, high-dose chemotherapy with subsequent autologous stem cell transplantation; HD-MTX, high-dose methotrexate; i.c.v.= administration via an intrathecal reservoir; i.v., intravenous; p. o., per os

eTable 1. Studies currently recruiting in Germany.

| MATRIX | Multicenter phase III trial on high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation compared with conventional chemotherapy for consolidation in primary CNS lymphoma Age: 18–65 years (65–70 years only if ECOG status 0–1) |

| MARTA | Multicenter phase II study on age-adapted high-dose therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in fit older patients with newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma Age: >70 years, ECOG status ≤ 2 (65–70 if patients are not eligible for MATRIX)) |

| PQR309 | Open, non-randomized phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pan-PI3K and mTOR PQR309 in patients with relapsed or refractory primary CNS lymphoma Age ≥18 years, Karnofsky index (KPS) ≥70% |

| NOA-13 | Prospective observational study on chemotherapy in non-specifically pre-treated patients with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status; CNS, central nervous system

Radiotherapy

In the majority of patients, percutaneous fractionated whole-brain radiotherapy leads to fast and usually complete remission; however, recurrences occur early. Median survival is only 12 to 18 months (35). With combined chemoradiotherapy, tumor control can be significantly improved and—in prospective studies—median survival times of 31 to 90 months have been achieved (30, 36– 40, e1). However, neurotoxicity occurring over a time course of months to years has emerged as a very serious problem. Affected patients show marked leukoencephalopathy, leading to cortical/subcortical atrophy and, in some cases, to severe cognitive deficits, gait abnormalities, incontinence, and need for nursing care (e2). The 5-year incidence of overt neurotoxicity is 12% to 65%; it is associated with mortality rates of 16% to 66% and primarily affects patients aged >60 years (30, 36– 40, e1, e3– 5). Delayed neurotoxicity is also observed in patients receiving intensive chemotherapy (e1, e6); however, extensive neurocognitive analyses showed that, especially irradiation, has a negative impact on cognitive performance and quality of life (e5, e7).

In the so far largest randomized phase III study, consolidation whole-brain radiotherapy did not improve overall survival compared to HD-MTX–based chemotherapy (e1). Thus, it should not be not be performed on a routine basis (1, 2).

Strategies to maintain long-term remission

Several strategies to intensify conventional chemotherapy have been evaluated in prospective studies, in some cases with promising results; they may be equally effective compared to chemoradiotherapy (34, e3).

Non-myeloablative consolidation chemotherapy achieved an efficacy comparable to that of chemoradiotherapy (median overall survival >59 months) (e8). Likewise, a HD-MTX–based polychemotherapy combined with intensive intraventricular chemotherapy via a reservoir (“Bonn protocol“, [eTable 2]) achieved long recurrence-free survival (>80 months), especially in younger patients (e9, e10). However, the regimen did not find widespread adoption due to the high rate of reservoir infections (19%). Without intraventricular chemotherapy, these good results could not be reproduced (e11). No controlled studies have yet been conducted to further explore the role of intrathecal treatment.

Lymphoma cells persisting in the CNS are reached by myeloablative, high-dose consolidation chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (HD-ASCT) as this strategy achieves very high drug levels in the CNS. The efficacy of HD-ASCT was evaluated in several phase II studies on younger patients without major comorbidities. In this selected patient population, HD-ASCT was a highly effective treatment option with curative potential (overall response 80–96%, median overall survival 64–104 months) (e12– 14). More recent data indicate that HD-ASCT provides equal efficacy to consolidation whole-brain radiotherapy, but is associated with less neurotoxic adverse events (34). In prospective studies, HD-ASCT has been associated with a mortality of 0% to 12% (e13, e14), but, because of its toxicity, especially older patients are often not eligible for it. Thus, ongoing studies are evaluating an age-adapted HD-ASCT for patients aged >65 years (eTable 1). The value of the various consolidation strategies (non-myeloablative versus myeloablative) is being explored in randomized trials in Germany too (28, e15) (eTable 1). Until solid data have become available, no reliable conclusions can be drawn.

Management of recurrence

About one third of all PCNSL patients are primarily refractory to treatment and at least half of the patients with initial response to treatment experience a relapse (e16, e17). So far, no standard of care has been established for this situation; the majority of treatment recommendations are based on retrospective and a few prospective studies (28).

According to reviews, the overall response rates of recurrences range from 10% to 85%; however, remissions are short-lived (median progression-free survival [PFS] approx. three months) (28). In patients with long-lasting remission after initial treatment (median 24–26 months), re-exposure to HD-MTX–containing chemotherapy proved effective with a high response rate (85–91%) and a median survival of 41 to 62 months (e18, e19). For patients aged <65 years, promising data on HD-ASCT are available from the Freiburg ZNS-NHL study (2-year survival: 56%) which is now established in many German centers (e20) (eTable 2). With HD-ASCT, long-term remission was achieved even in cases with no response to HD-MTX–based induction (e20, e21). Other published regimens to treat recurrence include pemetrexed (e22), topotecan (e23), temozolomide in combination with rituximab (e24), the PCV regimen (procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine) (e25), and rituximab and ifosfamide plus etoposide (e26). With response rates of 74% to 79% and a median survival of 10 to 16 months, whole-brain radiotherapy for recurrence is an effective treatment option (e27, e28). However, it should be used late in the course of the disease, if possible, as it is associated with a high rate of severe neurotoxic adverse events among patients with prior intensive chemotherapy (e28).

New active substances and immunotherapies

In refractory patients with multiple previous therapies, substances, such as temsirolimus (e29), lenalidomide (e30) and ibrutinib (e31), which interfere with B-cell receptor signaling and thus have an effect on proliferation and survival of lymphoma cells, and so-called checkpoint inhibitors (e32), which modulate T cell–mediated immune response, show activity, but are associated with significant toxicity in some patients. Should their efficacy and tolerability be confirmed in the currently recruiting studies, new treatment options for patients with PCNSL may become available.

Special patient populations

Management of older patients

The treatment of elderly patients is limited by comorbidities and the increased risk of treatment-related side effects. HD-MTX–based polychemotherapy is safe and effective as long as renal function is taken into account (dose reduction if creatinine clearance <100 mL/min) (29). Complete remissions are achieved in 36% to 60% of patients; however, median overall survival is only 14 to 31 months (e6, e33, e34) (table). In the German-speaking countries, many centers have adopted the PRIMAIN protocol (rituximab, methotrexate, procarbazine, [eTable 2]) which was evaluated in a large, randomized, multicenter study (e33).

If HD-MTX is contraindicated, patients can be treated with temozolomide for which an overall response of 47% and overall survival of 21 months was found in a retrospective analysis (e35). Given the high risk of neurotoxic adverse events, whole-brain radiotherapy should only be used if other treatment alternatives are not available or have been exhausted (2).

See the eSupplement for the sections “Management of vitreoretinal lymphoma“ and “Management of immunocompromised patients“.

Follow-up care

The follow-up should be based on neurological examination and cranial magnetic resonance imaging; other investigations are only recommended if specific abnormalities are suspected. The requirements for complete remission include the complete disappearance of contrast-enhancing lesions, the absence of malignant cells in the cerebrospinal fluid, and the complete disappearance of previous ocular involvement. All patients should undergo imaging and clinical follow-up examinations at 3-month intervals for 2 years, then at 6-month intervals for 3 years and finally at 1-year intervals for 5 years (2). Additional checks should be performed to assess any suspected abnormalities. With regard to potential neurotoxic late complications, it is advisable that patients receive follow-up care in a neuro-oncological center.

Conclusion

Because of its specific biological and clinical features, the diagnosis and treatment of PCNSL is challenging and requires an interdisciplinary approach. Thus, it is crucial that patients are preferably treated in centers experienced in the management of the disease and in the setting of a clinical study.

Supplementary Material

eSUPPLEMENT

• The management of vitreoretinal lymphoma

Almost all patients with isolated vitreoretinal lymphoma develop a CNS manifestation over the course of the disease (e36). Whether its management should be based on local strategies alone (ocular radiation therapy, intravitreal MTX-/rituximab injections) or on systemic approaches analog to the treatment of PCNSL, remains the subject of controversy (e36). In two retrospective case series, systemic therapy provided no survival benefit compared to local treatment alone (e37, e38); thus, it may be justified to delay the initiation of systemic therapy until the occurrence of a CNS manifestation.

If patients present with both ocular and CNS involvement, treatment as in patients with CNS involvement alone is recommended, because local treatment in addition to systemic therapy does not appear to improve survival (e39).

• Management of immunosuppressed patients

The data available on the management of PCNSL in immunocompromised patients is limited to small case series. Patients with HIV-associated PCNSL benefit from highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) (e40). In patients after organ transplantation, immunosuppressive therapy should be reduced or modified. If possible, immunosuppressed PCNSL patients should receive the same therapy as immunocompetent patients (e41). A single-center case series showed that selected patients may also be eligible for HD-MTX/rituximab treatment with subsequent HD-ASCT (e42).

• Interdisciplinary networking

The CNS lymphoma study group of the German Competence Network Malignant Lymphoma (Kompetenznetzes für maligne Lymphome, KML), the CNS-NHL study group of the German Lymphoma Alliance (GLA), and the interdisciplinary consortium Network Lymphomas and Lymphomatoid Lesions in the Nervous System (Netzwerk Lymphome und lymphomatoide Läsionen des Nervensystems, NLLLN) (e45) are important integrated platforms for sharing clinical and scientific information and for coordinating clinical studies. In addition, the NLLLN offers consultancy services (second opinions) and support in the management of complex cases. The guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of PCNSL were published with contributions from the authors (see e46) and are currently being revised.

Figure 4.

Histology of the primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL). Blast CD20-positive lymphoma cells infiltrate the brain parenchyma in a lawn-like pattern and spread, partly in groups, partly as solitary cells, in the brain tissue. The star marks a blood vessel with dense wall infiltration by small bystander lymphocytes. In the outer layers of the blood vessel wall adjacent to this layer, lymphoma cells are noted. Anti-CD20 immunohistochemistry, mild counterstaining with hemalum, original magnification × 200

Key Messages.

Clinical and imaging findings can be nonspecific—consequently, PCNSL should always be included in the differential diagnosis of space-occupying lesions of the brain and steroid treatment should be avoided prior to histopathological confirmation of the diagnosis to improve the diagnostic sensitivity of the biopsy.

The first-line treatment for PCNSL is HD-MTX–based polychemotherapy; treatment protocols commonly used for the various age groups in the German-speaking countries (Bonn protocol, Freiburg protocol, Matrix protocol, Primain protocol) are listed in the eSupplement.

Radiotherapy should be avoided in the first-line treatment of PCNSL and be reserved for patients with relapse or those with contraindications to chemotherapy.

Given the very high toxic potential of the therapies for PCNSL, patients should preferably be treated in a center experienced in the management of the disease.

In general, it is recommended that treatment decisions be made by multidisciplinary teams, e.g. dedicated brain tumor or lymphoma boards.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ralf Thoene, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Illerhaus has received consultancy fees from Riemser. He has received fees for conference participation and reimbursement of travel and accommodation expenses from Riemser and Roche. He has been contracted and received fees for the conduction of clinical trials from Riemser.

Dr. Korfel has received consultancy fees and fees for preparing continuing medical education events from PIQUR, Mundipharma, and Riemser.

Prof. Schlegel has received lecture fees for Neuro-update from medupdate.

Prof. Dreyling has received consultancy fees from Bayer, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Mundipharma, Roche, and Sandoz. He has received fees for preparing continuing medical education events from Bayer, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, and Roche. He has received financial support from Celegne, Janssen, Mundipharma, and Roche for a research project that he initiated.

Dr. von Baumgarten and Prof. Deckert declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Korfel A, Schlegel U. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoang-Xuan K, Bessell E, Bromberg J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: guidelines from the European Association for Neuro-Oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e322–e332. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deckert M, Brunn A, Montesinos-Rongen M, Terreni MR, Ponzoni M. Primary lymphoma of the central nervous system—a diagnostic challenge. Hematol Oncol. 2014;32:57–67. doi: 10.1002/hon.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 world health organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman S, Propp JM, McCarthy BJ. Temporal trends in incidence of primary brain tumors in the United States, 1985-1999. Neuro Oncol. 2006;8:27–37. doi: 10.1215/S1522851705000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Besson C, et al. Trends in primary central nervous system lymphoma incidence and survival in the US . Br J Haematol. 2016;174:417–424. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendez JS, Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, et al. The elderly left behind—changes in survival trends of primary central nervous system lymphoma over the past four decades. Neuro Oncol. 2018;206:87–94. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deckert M, Engert A, Bruck W, et al. Modern concepts in the biology, diagnosis, differential diagnosis and treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Leukemia. 2011;25:1797–1807. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasenda B, Ferreri AJ, Marturano E, et al. First-line treatment and outcome of elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL)—a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015;7:1305–1313. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuker W, Nagele T, Korfel A, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphomas (PCNSL): MRI features at presentation in 100 patients. J Neurooncol. 2005;72:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-3390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buhring U, Herrlinger U, Krings T, Thiex R, Weller M, Kuker W. MRI features of primary central nervous system lymphomas at presentation. Neurology. 2001;57:393–396. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai R, Rosenblum MK, DeAngelis LM. Primary CNS lymphoma: a whole-brain disease? Neurology. 2002;59:1557–1562. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000034256.20173.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pirotte B, Levivier M, Goldman S, Brucher JM, Brotchi J, Hildebrand J. Glucocorticoid-induced long-term remission in primary cerebral lymphoma: case report and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 1997;32:63–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1005733416571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathew BS, Carson KA, Grossman SA. Initial response to glucocorticoids. Cancer. 2006;106:383–387. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruck W, Brunn A, Klapper W, et al. [Differential diagnosis of lymphoid infiltrates in the central nervous system: experience of the network lymphomas and lymphomatoid lesions in the nervous system] Pathologe. 2013;34:186–197. doi: 10.1007/s00292-013-1742-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreth FW, Muacevic A, Medele R, Bise K, Meyer T, Reulen HJ. The risk of haemorrhage after image guided stereotactic biopsy of intra-axial brain tumours— a prospective study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2001;143:539–545. doi: 10.1007/s007010170058. discussion 45-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Royer-Perron L, Hoang-Xuan K, Alentorn A. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: time for diagnostic biomarkers and biotherapies? Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30:669–676. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porter AB, Giannini C, Kaufmann T, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma can be histologically diagnosed after previous corticosteroid use: a pilot study to determine whether corticosteroids prevent the diagnosis of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:662–667. doi: 10.1002/ana.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrey LE, Batchelor TT, Ferreri AJ, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize baseline evaluation and response criteria for primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5034–5043. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreri AJ, Reni M, Zoldan MC, Terreni MR, Villa E. Importance of complete staging in non-hodgkin‘s lymphoma presenting as a cerebral mass lesion. Cancer. 1996;77:827–833. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960301)77:5<827::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahnke K, Hummel M, Korfel A, et al. Detection of subclinical systemic disease in primary CNS lymphoma by polymerase chain reaction of the rearranged immunoglobulin heavy-chain genes. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4754–4757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunn A, Nagel I, Montesinos-Rongen M, et al. Frequent triple-hit expression of MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 in primary lymphoma of the central nervous system and absence of a favorable MYC(low)BCL2 (low) subgroup may underlie the inferior prognosis as compared to systemic diffuse large B cell lymphomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montesinos-Rongen M, Schafer E, Siebert R, Deckert M. Genes regulating the B cell receptor pathway are recurrently mutated in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:905–906. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montesinos-Rongen M, Godlewska E, Brunn A, Wiestler OD, Siebert R, Deckert M. Activating L265P mutations of the MYD88 gene are common in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:791–792. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0891-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montesinos-Rongen M, Schmitz R, Brunn A, et al. Mutations of CARD11 but not TNFAIP3 may activate the NF-kappaB pathway in primary CNS lymphoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:529–535. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreri AJ, Blay JY, Reni M, et al. Prognostic scoring system for primary CNS lymphomas: the international extranodal lymphoma study group experience. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:266–272. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weller M, Martus P, Roth P, Thiel E, Korfel A , German PCNSL Study Group Surgery for primary CNS lymphoma? Challenging a paradigm. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:1481–1484. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grommes C, DeAngelis LM. Primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2410–2418. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.7602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jahnke K, Korfel A, Martus P, et al. High-dose methotrexate toxicity in elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:445–449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferreri AJ, Reni M, Foppoli M, et al. High-dose cytarabine plus high-dose methotrexate versus high-dose methotrexate alone in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cobert J, Hochberg E, Woldenberg N, Hochberg F. Monotherapy with methotrexate for primary central nervous lymphoma has single agent activity in the absence of radiotherapy: a single institution cohort. J Neurooncol. 2010;98:385–393. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergner N, Monsef I, Illerhaus G, Engert A, Skoetz N. Role of chemotherapy additional to high-dose methotrexate for primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009355.pub2. CD009355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferreri AJ, Cwynarski K, Pulczynski E, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab (MATRix regimen) in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: results of the first randomisation of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group-32 (IELSG32) phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e217–e227. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferreri AJM, Cwynarski K, Pulczynski E, et al. Whole-brain radiotherapy or autologous stem-cell transplantation as consolidation strategies after high-dose methotrexate-based chemoimmunotherapy in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: results of the second randomisation of the international extranodal lymphoma study group-32 phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e510–e523. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson DF. Radiotherapy in the treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) J Neurooncol. 1999;43:241–247. doi: 10.1023/a:1006206602918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeAngelis LM, Seiferheld W, Schold SC, Fisher B, Schultz CJ Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study. Combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study 93-10. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4643–4648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poortmans PM, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Haaxma-Reiche H, et al. High-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy followed by consolidating radiotherapy in non-AIDS-related primary central nervous system lymphoma: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Lymphoma Group Phase II Trial 20962. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4483–4488. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korfel A, Martus P, Nowrousian MR, et al. Response to chemotherapy and treating institution predict survival in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:177–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glass J, Won M, Schultz CJ, et al. Phase I and II study of induction chemotherapy with methotrexate, rituximab, and temozolomide, followed by whole-brain radiotherapy and postirradiation temozolomide for primary CNS lymphoma: NRG oncology RTOG 0227. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1620–1625. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris PG, Correa DD, Yahalom J, et al. Rituximab, methotrexate, procarbazine, and vincristine followed by consolidation reduced-dose whole-brain radiotherapy and cytarabine in newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: final results and long-term outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3971–3979. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Thiel E, Korfel A, Martus P, et al. High-dose methotrexate with or without whole brain radiotherapy for primary CNS lymphoma (G-PCNSL-SG-1): a phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1036–1047. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Abrey LE, DeAngelis LM, Yahalom J. Long-term survival in primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:859–863. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Kasenda B, Loeffler J, Illerhaus G, Ferreri AJ, Rubenstein J, Batchelor TT. The role of whole brain radiation in primary CNS lymphoma. Blood. 2016;128:32–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-650101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Correa DD, Shi W, Abrey LE, et al. Cognitive functions in primary CNS lymphoma after single or combined modality regimens. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:101–108. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Doolittle ND, Korfel A, Lubow MA, et al. Long-term cognitive function, neuroimaging, and quality of life in primary CNS lymphoma. Neurology. 2013;81:84–92. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318297eeba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Hoang-Xuan K, Taillandier L, Chinot O, et al. Chemotherapy alone as initial treatment for primary CNS lymphoma in patients older than 60 years: a multicenter phase II study (26952) of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2726–2731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Herrlinger U, Schafer N, Fimmers R, et al. Early whole brain radiotherapy in primary CNS lymphoma: negative impact on quality of life in the randomized G-PCNSL-SG1 trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;1431:815–821. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Rubenstein JL, Hsi ED, Johnson JL, et al. Intensive chemotherapy and immunotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: CALGB 50202 (Alliance 50202) J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3061–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.9957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Pels H, Schmidt-Wolf IG, Glasmacher A, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: results of a pilot and phase II study of systemic and intraventricular chemotherapy with deferred radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4489–4495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Juergens A, Pels H, Rogowski S, et al. Long-term survival with favorable cognitive outcome after chemotherapy in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:182–189. doi: 10.1002/ana.21824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Pels H, Juergens A, Glasmacher A, et al. Early relapses in primary CNS lymphoma after response to polychemotherapy without intraventricular treatment: results of a phase II study. J Neurooncol. 2009;91:299–305. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9712-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Illerhaus G, Kasenda B, Ihorst G, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem cell transplantation for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: a prospective, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e388–e397. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Illerhaus G, Marks R, Ihorst G, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell transplantation and hyperfractionated radiotherapy as first-line treatment of primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3865–3870. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Omuro A, Correa DD, DeAngelis LM, et al. R-MPV followed by high-dose chemotherapy with TBC and autologous stem-cell transplant for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:1403–1410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-604561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Schorb E, Finke J, Ferreri AJ, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant compared with conventional chemotherapy for consolidation in newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma—a randomized phase III trial (MATRix) BMC Cancer. 2016;16 doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2311-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Langner-Lemercier S, Houillier C, Soussain C, et al. Primary CNS lymphoma at first relapse/progression: characteristics, management, and outcome of 256 patients from the French LOC Network. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:1297–1303. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Jahnke K, Thiel E, Martus P, et al. Relapse of primary central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features, outcome and prognostic factors. J Neurooncol. 2006;80:159–165. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Plotkin SR, Betensky RA, Hochberg FH, et al. Treatment of relapsed central nervous system lymphoma with high-dose methotrexate. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5643–5646. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Pentsova E, Deangelis LM, Omuro A. Methotrexate re-challenge for recurrent primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurooncol. 2014;117:161–165. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1370-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Kasenda B, Ihorst G, Schroers R, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous haematopoietic stem cell support for relapsed or refractory primary CNS lymphoma—a prospective multicentre trial by the German Cooperative PCNSL study group. Leukemia. 2017;312:623–629. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Soussain C, Choquet S, Fourme E, et al. Intensive chemotherapy with thiotepa, busulfan and cyclophosphamide and hematopoietic stem cell rescue in relapsed or refractory primary central nervous system lymphoma and intraocular lymphoma: a retrospective study of 79 cases. Haematologica. 2012;97:1751–1756. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.060434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Zhang JP, Lee EQ, Nayak L, et al. Retrospective study of pemetrexed as salvage therapy for central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurooncol. 2013;115:71–77. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Fischer L, Thiel E, Klasen HA, et al. Prospective trial on topotecan salvage therapy in primary CNS lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1141–1145. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Nayak L, Abrey LE, Drappatz J, et al. Multicenter phase II study of rituximab and temozolomide in recurrent primary central nervous system lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:58–61. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.698736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Herrlinger U, Brugger W, Bamberg M, Kuker W, Dichgans J, Weller M. PCV salvage chemotherapy for recurrent primary CNS lymphoma. Neurology. 2000;54:1707–1708. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.8.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Mappa S, Marturano E, Licata G, et al. Salvage chemoimmunotherapy with rituximab, ifosfamide and etoposide (R-IE regimen) in patients with primary CNS lymphoma relapsed or refractory to high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy. Hematol Oncol. 2013;31:143–150. doi: 10.1002/hon.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Nguyen PL, Chakravarti A, Finkelstein DM, Hochberg FH, Batchelor TT, Loeffler JS. Results of whole-brain radiation as salvage of methotrexate failure for immunocompetent patients with primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1507–1513. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Hottinger AF, DeAngelis LM, Yahalom J, Abrey LE. Salvage whole brain radiotherapy for recurrent or refractory primary CNS lymphoma. Neurology. 2007;69:1178–1182. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000276986.19602.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Korfel A, Schlegel U, Herrlinger U, et al. Phase II trial of temsirolimus for relapsed/refractory primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1757–1763. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.9897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Rubenstein JL, Formaker P, Wang X, et al. Lenalidomide is highly active in recurrent CNS lymphomas: phase I investigation of lenalidomide plus rituximab and outcomes of lenalidomide as maintenance monotherapy. JCO. 2016;34(7502) [Google Scholar]

- E31.Lionakis MS, Dunleavy K, Roschewski M, et al. Inhibition of B cell receptor signaling by Ibrutinib in Primary CNS Lymphoma. Cancer cell. 2017;31:833–843. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.04.012. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Nayak L, Iwamoto FM, LaCasce A, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed/refractory primary central nervous system and testicular lymphoma. Blood. 2017;129:3071–3073. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-01-764209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Fritsch K, Kasenda B, Schorb E, et al. High-dose methotrexate-based immuno-chemotherapy for elderly primary CNS lymphoma patients (PRIMAIN study) Leukemia. 2017;31:846–852. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Omuro A, Chinot O, Taillandier L, et al. Methotrexate and temozolomide versus methotrexate, procarbazine, vincristine, and cytarabine for primary CNS lymphoma in an elderly population: an intergroup ANOCEF-GOELAMS randomised phase 2 trial. The Lancet Haematology. 2015;2:e251–e259. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Kurzwelly D, Glas M, Roth P, et al. Primary CNS lymphoma in the elderly: temozolomide therapy and MGMT status. J Neurooncol. 2010;97:389–392. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Fend F, Ferreri AJ, Coupland SE. How we diagnose and treat vitreoretinal lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2016;173:680–692. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Grimm SA, Pulido JS, Jahnke K, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma: an International Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Collaborative Group report. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1851–1855. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Riemens A, Bromberg J, Touitou V, et al. Treatment strategies in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: a 17-center European collaborative study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:191–197. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.4755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Grimm SA, McCannel CA, Omuro AM, et al. Primary CNS lymphoma with intraocular involvement: International PCNSL Collaborative Group report. Neurology. 2008;71:1355–1360. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327672.04729.8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Skiest DJ, Crosby C. Survival is prolonged by highly active antiretroviral therapy in AIDS patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. AIDS. 2003;17:1787–1793. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200308150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E41.Cavaliere R, Petroni G, Lopes MB, Schiff D, International Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Collaborative Group Primary central nervous system post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder: an International primary central nervous system lymphoma collaborative group report. Cancer. 2010;116:863–870. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Wieters I, Atta J, Kann G, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in HIV-related lymphoma in the rituximab era—a feasibility study in a monocentric cohort. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17 doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.4.19648. 19648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Pulczynski EJ, Kuittinen O, Erlanson M, et al. Successful change of treatment strategy in elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma by de-escalating induction and introducing temozolomide maintenance: results from a phase II study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Haematologica. 2015;100:534–540. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.108472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Kasenda B, Schorb E, Fritsch K, Finke J, Illerhaus G. Prognosis after high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation as first-line treatment in primary CNS lymphoma—a long-term follow-up study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2670–2675. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.NLLLN-Netzwerk Lymphome und lymphomatoide Läsionen des Nervensystems. http://pathologie-neuropathologie.uk-koeln.de/institut-fuer-neuropathologie/nllln (last accessed on 2 May 2018) [Google Scholar]

- E46.AWMF. Primäre ZNS-Lymphome. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/030-059.html (last accessed on 2 May 2018) [Google Scholar]

- E47.Ferreri AJ. How I treat primary CNS lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:510–522. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-321349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eSUPPLEMENT

• The management of vitreoretinal lymphoma

Almost all patients with isolated vitreoretinal lymphoma develop a CNS manifestation over the course of the disease (e36). Whether its management should be based on local strategies alone (ocular radiation therapy, intravitreal MTX-/rituximab injections) or on systemic approaches analog to the treatment of PCNSL, remains the subject of controversy (e36). In two retrospective case series, systemic therapy provided no survival benefit compared to local treatment alone (e37, e38); thus, it may be justified to delay the initiation of systemic therapy until the occurrence of a CNS manifestation.

If patients present with both ocular and CNS involvement, treatment as in patients with CNS involvement alone is recommended, because local treatment in addition to systemic therapy does not appear to improve survival (e39).

• Management of immunosuppressed patients

The data available on the management of PCNSL in immunocompromised patients is limited to small case series. Patients with HIV-associated PCNSL benefit from highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) (e40). In patients after organ transplantation, immunosuppressive therapy should be reduced or modified. If possible, immunosuppressed PCNSL patients should receive the same therapy as immunocompetent patients (e41). A single-center case series showed that selected patients may also be eligible for HD-MTX/rituximab treatment with subsequent HD-ASCT (e42).

• Interdisciplinary networking

The CNS lymphoma study group of the German Competence Network Malignant Lymphoma (Kompetenznetzes für maligne Lymphome, KML), the CNS-NHL study group of the German Lymphoma Alliance (GLA), and the interdisciplinary consortium Network Lymphomas and Lymphomatoid Lesions in the Nervous System (Netzwerk Lymphome und lymphomatoide Läsionen des Nervensystems, NLLLN) (e45) are important integrated platforms for sharing clinical and scientific information and for coordinating clinical studies. In addition, the NLLLN offers consultancy services (second opinions) and support in the management of complex cases. The guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of PCNSL were published with contributions from the authors (see e46) and are currently being revised.