Abstract

The antibacterial resistance and virulence genotypes and phenotypes of 148 non-duplicate Klebsiella pneumoniae strains collected from 112 patients in Moscow hospitals in 2012–2016 including isolates from the respiratory system (57%), urine (30%), wounds (5%), cerebrospinal fluid (4%), blood (3%), and rectal swab (1%) were determined. The majority (98%) were multidrug resistant (MDR) strains carrying blaSHV (91%), blaCTX-M (74%), blaTEM (51%), blaOXA (38%), and blaNDM (1%) beta-lactamase genes, class 1 integrons (38%), and the porin protein gene ompK36 (96%). The beta-lactamase genes blaTEM-1, blaSHV-1, blaSHV-11, blaSHV-110, blaSHV-190, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-3, blaCTX-M-55, blaOXA-48, blaOXA-244, and blaNDM-1 were detected; class 1 integron gene cassette arrays (aadA1), (dfrA7), (dfrA1-orfC), (aadB-aadA1), (dfrA17-aadA5), and (dfrA12-orfF-aadA2) were identified. Twenty-two (15%) of clinical K. pneumoniae strains had hypermucoviscous (HV) phenotype defined as string test positive. The rmpA gene associated with HV phenotype was detected in 24% of strains. The intrapersonal mutation of rmpA gene (deletion of one nucleotide at the polyG tract) was a reason for negative hypermucoviscosity phenotype and low virulence of rmpA-positive K. pneumoniae strain KPB584. Eighteen virulent for mice strains with LD50 ≤ 104 CFU were attributed to sequence types ST23, ST86, ST218, ST65, ST2174, and ST2280 and to capsular types K1, K2, and K57. This study is the first report about hypervirulent K. pneumoniae strain KPB2580-14 of ST23K1 harboring extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15 and carbapenemase OXA-48 genes located on pCTX-M-15-like and pOXA-48-like plasmids correspondingly.

Keywords: Klebsiella pneumoniae, antibacterial resistance, virulence, MLST, K-serotype

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is one of the main pathogens of hospital infections and causes bacteremia and infections of the respiratory tract, skin, urinary tract and central nervous system. Two independent evolutionary branches of K. pneumoniae have been described: classical (cKP) and hypervirulent (hvKP). Modern cKP strains are causative agents of pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and other infections in people with low immune status; these strains are characterized by multi drug resistance (MDR) associated with the production of beta-lactamases (including extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases), activation of efflux pumps, and changes in the structure of porin proteins [1]. K. pneumoniae hvKP causes primary infections in people with normal immunity (acute liver abscesses, septicemia, and meningitis) and can metastasize from the primary focus of infection to other organs and tissues of the body [2–4]. Infections caused by hvKP have a high mortality rate of up to 31% [5]. Virulence factors of hvKP include a hypermucoviscous phenotype, iron assimilation, allantoin recycling, lipopolysaccharide and polysaccharide capsule synthesis and type I fimbriae [1,6]. Most virulent K. pneumoniae strains are hypermucoviscous and belong to the K1, K2, K5, K20, K54, and K57 capsular serotypes and to ST23, ST29, ST65, ST86, ST268, ST375, ST412, and ST420 sequence types [3,5]. It was currently considered, that clonal complexes of hvKP and MDR strains are non-overlapping [7]. However, the acquisition of multiple antibacterial resistance by epidemic hvKP strains has been reported in the last decade, including a hvKP ST23K1 clone harboring the blaKPC-2 gene in Argentine, blaCTX-M-3 gene in France, and blaCTX-M-15 gene in South Korea; a hvKP ST1797K1 clone acquired carbapenemase gene blaKPC-2 in China; and a hvKP ST86 clone acquired cephalosporinase blaCTX-M-14/15 gene in Australia [8–12].

The aims of this study were (i) to determine the virulence and antibacterial resistance phenotypes and genotypes of clinical K. pneumoniae strains isolated in Russia in 2012–2016 with a particular emphasis on the investigation of virulent strains and their distinctness from other strains; (ii) to characterize the virulent strains with respect to capsular type, sequence type, and experimental virulence in mice. (iii) to determine the distribution of antibiotic resistance genes among K. pneumoniae with different virulence gene profiles.

Materials and methods

Bioethical requirements

In accordance with the requirements of the Russian Federation Bioethical Committee, each patient signed an agreement with the hospital consenting to treatment and laboratory examination. This agreement was filed in the medical history of each patient. The materials used in the study did not contain personal data of patients because the labeling of the clinical isolates did not include name, date of birth, address, disease history, or other personal information. Personal data were erased when the monitoring tables were generated. Overall, the study was a prospective observational study; all patients received the same medical treatment according to clinical indications.

Bacterial strains, identification, and growth conditions

K. pneumoniae strains used in this study were isolated from clinical samples, including patient specimens (respiratory system, urine, wounds, cerebrospinal fluid, blood, and rectal swab) collected in the Burdenko Neurosurgery Institution (n = 106), Moscow Infectious Hospital No. 1 (n = 25), and other sources (n = 17). Additionally, one K. pneumoniae strain, KPM9, was isolated from the environment (fresh-water) in the Krasnodar Region of Russia in 2011 during mice epizooty; this strain was used as a reference strain virulent for mice [13].

Bacterial identification was performed using a Vitek-2 Compact instrument with a VITEK® 2 Gram-negative (GN) ID card (SKU number 21341; BioMérieux, Paris, France) and a MALDI-TOF Biotyper (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) instrument capable of distinguishing among K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae ssp. ozaenae, K. pneumoniae ssp. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae ssp. rhinoscleromatis, and K. variicola. Bacterial isolates were stored in 15% glycerol at minus 80 °C.

Bacterial cultures were grown at 37 °C on Nutrient Medium No. 1 (SRCAMB, Obolensk, Russia), Luria-Bertani broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) and Muller-Hinton broth (Himedia, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India).

Hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae strains were identified using the string test [6]. The test was considered positive if a colony of K. pneumoniae could be ‘stretched’ more than 5 mm using a standard bacteriological loop.

Susceptibility to antibacterial agents

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibacterials belonging to eight functional classes (beta-lactams, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, phenicols, aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, nitrofurans, and phosphomycins) were determined using a Vitek-2 device with VITEK-2 AST N-101 and AST N-102 cards (BioMérieux, Paris, France). The results were interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/). E. coli strains ATCC 25922 and ATCC 35218 were used for quality control.

Virulence assessment of K. pneumoniae strains

All protocols for animal experiments were approved by the State Research Center for Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology Bioethics Committee (Permit No: VP-2014/1). K. pneumoniae virulence (LD50) was evaluated in female outbred white mice weighing 18–22 g obtained from the ‘Andreevka’ Laboratory Animals Nursery (SCBT, Moscow region, Russia). The mice were housed under standard conditions in accordance with international standards and requirements [14]. The mice were infected intraperitoneally with K. pneumoniae cells using six mice per infective dose. The actual number of bacteria present was determined by plating on agar medium. The specificity of K. pneumoniae infection was confirmed by isolation of K. pneumoniae from the liver, spleen, and lungs. The LD50 was calculated using the Karber method [15].

PCR detection of antibacterial resistance, virulence, and K serotype-specific genes

Genes associated with K. pneumoniae virulence (rmpA, aer, uge2, wabG, kfu, fimH, and allR) or antibacterial resistance (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaOXA-48-like, blaNDM, blaKPC, blaVIM, blaIMP, ompK36, and class 1 and 2 integrons) were detected by PCR using previously described specific primers [16–22]. The capsular serotypes of the K. pneumoniae strains were determined using specific primers for wzy genes associated with K serotypes K1, K2, K5, K20, K54, and K57 and by wzi gene sequencing (Supplementary Data Table 1). Bacterial thermolysates were used as DNA templates for amplification using a GradientPalmCycler (Corbert Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia) and Thercyc cycler (DNA-Technology, Protvino, Moscow region, Russia) [23]. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels.

DNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Whole-genome sequencing was performed using the Illumina MiSeq instrument according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). DNA libraries were prepared using Nextera DNA Library Preparation Kit. Miseq Reagent Kit v3 (300 cycles) was used for sequencing. Reads were de novo assembled using SPAdes v. 3.9 (http://bioinf.spbau.ru/spades). Basic Local Alignment Search – BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) was used for searching homologous sequences. Program MAUVE (http://darlinglab.org/mauve/mauve.html) was used for multiple genome alignments.

Sequencing of separate genes and DNA fragments was carried out using the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator v.3.1 kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Purified products were analyzed on an ABI PRISM 3100-Avant automated DNA Sequencer at the SINTOL Center for collective use (Moscow, Russia). DNA sequences were analyzed using Vector NTI9 (Invitrogen, USA) and BLAST. Class 1 and 2 integrons were analyzed using the INTEGRAL database (http://integrall.bio.ua.pt/?). The DNA sequences of 411 genes have been deposited in the GenBank database (Supplementary Data Table 2).

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of K. pneumoniae strains carrying different sets of virulence genes and exhibiting different virulence in mice was performed by determining the nucleotide sequences of seven housekeeping genes as described previously [24]. The features of the 38 K. pneumoniae strains attributed to 12 sequence types have been deposited in the MLST PASTEUR database (Supplementary Data Table 3).

Phylogenetic analysis

Complete genome sequence data of 65 K. pneumoniae strains from the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database isolated in different geographical areas and KPB2580 strain were used to generate bacterial core genome SNPs by the Wombac 2.0 software (http://www.mybiosoftware.com/wombac-1-1-bacterial-core-genome-snps-phylogenomic-trees-ngs-reads-andor-draft-genomes.html). The trees were constructed by using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstraps implemented in SplitsTree [25].

Results and discussion

Bacterial strains

One hundred and forty-eight K. pneumoniae strains were isolated in 2012-16 from 112 patients from the respiratory system (57%), urine (30%), wounds (5%), cerebrospinal fluid (4%), blood (3%), and rectal swab (1%). It should be noted, K. pneumoniae was one of the dominant pathogens among bacteria causing hospital infections in Moscow intensive care units (ICUs) under study during this period.

Antibacterial susceptibility and antibacterial resistance gene profiles

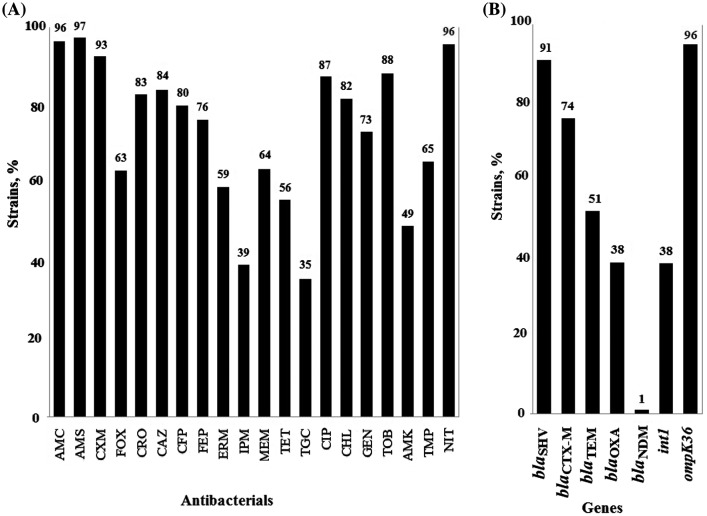

Most of K. pneumoniae strains (94%) in this study expressed the MDR phenotype, i.e. they were resistant to three or more classes of antibacterials, accordingly to Magiorakos et al. definitions [26]. Specifically, 31% strains were resistant to seven functional classes of antibacterials, 20% to six classes, 22% to five classes, 16% to four classes, and 5% to three classes. Most of the strains were resistant to beta-lactams, nitrofurans, fluoroquinolones, phenicols, and aminoglycosides. Of particular concern is the high level of resistance to reserve drugs: more than 1/3 of the strains were resistant to tigecycline with MIC > 2 mg/L and to imipenem with MIC ≥ 4 mg/L; almost half the strains were resistant to amikacin with MIC ≥ 16 mg/L (Figure 1(A)).

Figure 1.

Antibacterial resistance and resistance genes of 148 K. pneumoniae strains. (A) Rate of the strains resistant to antibacterials amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, AMC; amoxicillin/sulbactam, AMS; cefuroxime, CXM; cefoxitin, FOX; ceftriaxone, CRO; ceftazidime, CAZ; cefoperazone/sulbactam, CFP; cefepime, FEP; ertapenem, ERM; imipenem, IPM; meropenem, MEM; tetracycline, TET; tigecycline, TGC; ciprofloxacin, CIP; chloramphenicol, CHL; gentamicin, GEN; tobramycin, TOB; amikacin, AMK; trimethoprim, TMP; and nitrofurantoin, NIT; (B) Rate of the strains carrying beta-lactamase genes of blaSHV-type (blaSHV-1, blaSHV-11, blaSHV-110, blaSHV-190); blaCTX-M-type (blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-3, blaCTX-M-55); blaTEM-type (blaTEM-1); blaOXA-type (blaOXA-48, blaOXA-244); blaNDM-type (blaNDM-1); class 1 integrons; and ompK36 porin protein gene.

Beta-lactamase genes of blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaOXA, and blaNDM types were detected in the strains; blaKPC, blaVIM, and blaIMP types were not detected (Figure 1(B)). The following alleles of beta-lactamase genes were identified: blaTEM-1, blaSHV-1, blaSHV-11, blaSHV-110, blaSHV-190, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-3, blaCTX-M-55, blaOXA-48, blaOXA-244, and blaNDM-1. Ten combinations of five beta-lactamase gene types were identified in the strain collection (Table 1). Major (37% strains) carried three types, rarer (21, 20 and 16% strains) carried four, two, and one beta-lactamase gene types correspondingly. One strain (isolated in March of 2016 from the endotracheal aspirate of a patient on mechanical ventilation) K. pneumoniae KPB417-16 belonged to sequence type ST147, carried five beta-lactamase genes (blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaCTX-M-15, blaOXA-48, and blaNDM-1). Herewith the blaNDM-1 gene was first detected in Moscow hospital [27], although previously such gene was detected in K. pneumoniae of ST147 in the Northwest region of Russia in 2015 [28].

Table 1.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations of beta-lactams for K. pneumoniae strains carrying different sets of beta-lactamase genes.

| Beta-lactamase genes | Number of strains | MICs of beta-lactams (number of strains) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMS | CXM | CRO | CAZ | CFP | FEP | IPM | ||

| blaSHV | 1 | >32(1) | >64(1) | >64(1) | >64(1) | >64(1) | 16(1) | >16(1) |

| blaTEM | ||||||||

| blaCTX-M | ||||||||

| blaOXA | ||||||||

| blaNDM | ||||||||

| blaSHV | 31 | >32(31) | >64(31) | >64(31) | >8(31) | >16(31) | >8(31) | >16(9) |

| blaTEM | 8(5) | |||||||

| blaCTX-M | ≤2(17) | |||||||

| blaOXA | ||||||||

| blaSHV | 38 | >32(38) | >64(38) | >64(38) | >16(38) | >8(38) | >4(37) | >16(4) |

| blaTEM | 2(1) | 8(2) | ||||||

| blaCTX-M | ≤2(32) | |||||||

| blaSHV | 2 | >32(2) | >16(2) | 32(1) | ≤1(2) | >32(2) | ≤2(2) | 8(1) |

| blaTEM | 2(1) | ≤2(1) | ||||||

| blaOXA | ||||||||

| blaSHV | 15 | >32(15) | >64(15) | >64(15) | >64(15) | >16(15) | >8(15) | >16(4) |

| blaCTX-M | 8(7) | |||||||

| blaOXA | ≤2(4) | |||||||

| blaSHV | 3 | >32(3) | >16(2) | >16(2) | >64(2) | ≤1 | 128(1) | >256(1) |

| blaTEM | ≤16(1) | ≤1(1) | ≤1(1) | 2(1) | ≤1(2) | |||

| <1(1) | ||||||||

| blaSHV | 19 | >32(19) | >64(19) | >64(19) | >64(19) | >16(19) | >16(19) | >16(2) |

| blaCTX-M | 4(1) | |||||||

| ≤1(16) | ||||||||

| blaSHV | 7 | >32(7) | >16(5) | 2(4) | >64(1) | >32(6) | <1(1) | >16(6) |

| blaOXA | ≤16(2) | ≤1(3) | ≤1(6) | ≤1(1) | ≤1(1) | |||

| blaSHV | 18 | >32(18) | >16(2) | >2(3) | >64(4) | >1(1) | >4(4) | >16(4) |

| ≤16(16) | ≤1(15) | ≤1(14) | ≤1(17) | ≤1(14) | ≤1(14) | |||

| blaCTX-M | 6 | >32(6) | >64(6) | >64(6) | >64(6) | >16(6) | >16(6) | ≤1(6) |

| – | 8 | >32(4) | >16(4) | >2(4) ≤1(4) | >4(1) | >1(4) | >4(4) | >16(2) |

| ≤32(4) | ≤16(4) | ≤1(7) | ≤1(4) | 4(4) | 4(2) | |||

| ≤1(4) | ||||||||

| Total | 148 | >32(144) | >16(125) | >2(120) | >4(118) | >1(123) | >4(124) | >16(33) |

| ≤32(4) | ≤16(23) | 2(5) | ≤1(30) | ≤1(25) | 4(6) | 4-8(18) | ||

| ≤1(23) | ≤1(18) | ≤1(97) | ||||||

Notes: AMS, amoxicillin-sulbactam; CXM, cefuroxime; CRO, ceftriaxone; CAZ, ceftazidime; CFP, cefoperazone-sulbactam; FEP, cefepime; IPM, imipenem.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of beta-lactams for K. pneumoniae strains were different for various sets of beta-lactamase genes. Resistance to beta-lactams detected for the strains that have no beta-lactamase genes indicate the presence of additional molecular mechanisms, possibly other types of beta-lactamases, porin mutations and/or efflux pumps (Table 1). For example, recently we described K. pneumoniae strains carrying the insertions of IS1R and IS10R elements that inactivated the ompK36 gene, resulting in loss of the OmpK36 porin and raising resistance to imipenem [29]. Class 1 integrons detected in 38% of K. pneumoniae strains undoubtedly contributed to the resistance phenotype of these strains. Gene cassette arrays (aadA1), (dfrA7), (dfrA1-orfC), (aadB-aadA1), (dfrA17-aadA5), and (dfrA12-orfF-aadA2) were identified in 45% of class 1 integrons (Supplementary Data Table 3).

Virulence genes, hypermucoviscosity, capsular types, and virulence in mice

Seven K. pneumoniae genes associated with Klebsiella virulence factors [6,30] were detected by PCR. The most prevalent were intrinsic genes wabG (94% of strains) and uge2 (81%), which are involved in the synthesis of the polysaccharide capsule and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and fimH (91%), which encodes type I fimbria. Less common were kfu (29%) and aer (21%), which are associated with utilization of trivalent iron, and rmpA (24%), which is associated with a hypermucoviscous phenotype. The allantoin regulon gene allR was rarely detected in 7% of strains (Table 2). Twenty-two of clinical K. pneumoniae strains had hypermucoviscous (HV) phenotype defined as string test positive. They belonged to capsular types K1 (n = 10), K2 (n = 7), and K57 (n = 5). Moreover, capsular types K14, K47, K62, K60, K27, K28, and K420 were identified among HV-negative strains (Table 3).

Table 2.

Virulence gene combinations of K. pneumoniae strains.

| Virulence genes combination | Set of virulence genes | Number of strains |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | rmpA, aer, uge2, wabG, kfu, fimH, allR | 10 |

| 6 | rmpA, aer, uge2, wabG, kfu, fimH | 2 |

| 5a | rmpA, aer, uge2, wabG, fimH | 7 |

| 5b | rmpA, aer, wabG, kfu, fimH | 3 |

| 5c | rmpA, uge2, wabG, kfu, fimH | 1 |

| 5d | aer, uge2, wabG, kfu, fimH | 1 |

| 4a | uge2, wabG, kfu, fimH | 26 |

| 4b | rmpA, aer, wabG, fimH | 8 |

| 3a | uge2, wabG, fimH | 68 |

| 3b | rmpA, wabG, fimH | 4 |

| 2a | wabG, fimH | 4 |

| 2b | uge2, wabG | 5 |

| 1 | fimH | 1 |

| 0 | – | 8 |

| Total | 148 |

Note: ‘-’ gene was not detected.

Table 3.

Features of virulent and avirulent in mice Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (n = 38).

| Strain | Year | Source | String test | К-type | ST | Resistance to antibacterials: number groups (functional classes) | Beta-lactamase genes | Virulence genes arraya | LD50, CFU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPM9b | 2011 | Water | + | K20 | 1544 | 1 (BLA) | SHV-1 | 6 | 10 |

| KPS73 | 2016 | Lung | + | K1 | 23 | 1 (BLA) | SHV-1 | 7 | 44 |

| KPB1802K | 2013 | Trachea | + | K1 | 23 | 1 (BLA) | SHV-190 | 7 | 86 |

| KPI1683 | 2014 | Trachea | + | K1 | 23 | 2 (BLA NIT) | SHV-1 | 7 | 26 |

| KPI261 | 2014 | Trachea | + | K1 | 23 | 3 (BLA AMI NIT) | SHV-1, CTX-M-15 | 7 | 16 |

| KPB1493-1 | 2013 | Trachea | + | K1 | 23 | 6 (BLA TET QNL AMI SUL NIT) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15 | 7 | 4 × 102 |

| KPB463K-13 | 2013 | Trachea | + | K1 | 23 | 6 (BLA QNL AMI SUL NIT PHO) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 7 | 1 × 104 |

| KPB475-14 | 2014 | Urine | + | K1 | 23 | 7 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI SUL NIT) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 7 | 1 × 103 |

| KPB594-14 | 2014 | Wound | + | K1 | 23 | 7 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI SUL NIT) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 7 | 3 × 103 |

| KPB1103-14 | 2014 | Urine | + | K1 | 23 | 7 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI SUL NIT) | SHV-190, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 7 | 3 × 102 |

| KPB2580-14 | 2014 | Urine | + | K1 | 23 | 7 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI SUL NIT) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 7 | 17 |

| KPI1748 | 2014 | Trachea | + | K2 | 65 | 5 (BLA QNL CHL AMI SUL) | SHV-11 | 6 | 83 |

| KPB4010 | 2013 | Cerebrospinal fluid | + | K2 | 2280 | 3 (BLA TET NIT) | SHV-11 | 5a | 25 |

| KPI1627 | 2014 | Trachea | + | K2 | 86 | 2 (BLA NIT) | SHV-11 | 5a | 14 |

| KPI6208 | 2014 | Trachea | + | K2 | 86 | 3 (BLA TET NIT) | SHV-11 | 5a | 40 |

| KPB492-16 | 2016 | Wound | + | K2 | 86 | 1 (BLA) | SHV-11 | 5a | 1 × 103 |

| KPB463-16 | 2016 | Trachea | + | K2 | 86 | 1 (BLA) | SHV-11 | 5a | 1 × 103 |

| KPI3014 | 2014 | Trachea | + | K2 | 2174 | 6 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI NIT) | SHV-11, TEM-1 | 5d | 1 × 104 |

| KPB550 | 2013 | Urine | + | K57 | 218 | 5 (BLA QNL PHO NIT SUL) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 5b | 2 × 103 |

| KPB584 | 2013 | Urine | − | K57 | 218 | 4 (BLA SUL NIT PHO) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 5b | >106 |

| KPB500 | 2013 | Trachea | + | K57 | 218 | 5 (BLA QNL SUL NIT PHO) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-244 | 4b | >106 |

| KPB811K | 2013 | Cerebrospinal fluid | + | K57 | 218 | 5 (BLA QNL SUL NIT PHO) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-244 | 4b | >106 |

| KPB757K | 2013 | Urine | + | K57 | 218 | 8 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMK SUL NIT PHO) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-244 | 4b | >106 |

| KPB612-1 | 2013 | Trachea | + | K57 | 218 | 7 (BLA QNL AMI SUL PHO NIT CST) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 4b | >106 |

| KPB690-14K | 2014 | Urine | − | K57 | 218 | 5 (BLA QNL CHL AMI NIT) | SHV-11, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 2b | >106 |

| KPB542-15 | 2015 | Urine | − | K57 | 23 | 7 (BLA QNL CHL AMI SUL NIT PHO) | SHV-11, CTX-M-15 | 3b | >106 |

| KPI112 | 2014 | Trachea | − | K57 | 23 | 4 (BLA QNL AMI SUL) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-55 | 5c | >106 |

| KPB1493-2 | 2013 | Trachea | − | K62 | 48 | 4 (BLA CHL AMI NIT) | SHV-11, CTX-M-15 | 3a | >106 |

| KPB420-14 | 2014 | Urine | − | K62 | 48 | 7 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI SUL NIT) | SHV-11, CTX-M-15 | 2a | >106 |

| KPB1224 | 2012 | Trachea | − | K47 | 395 | 6 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI SUL) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 4a | >106 |

| KPB1667 | 2013 | Urine | − | K47 | 395 | 6 (BLA QNL CHL AMI SUL NIT) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 4a | >106 |

| KPB958-14 | 2014 | Urine | − | K14 | 147 | 7 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI SUL NIT) | SHV-11, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 4a | >106 |

| KPB417-16 | 2016 | Trachea | − | K14 | 147 | 4 (BLA QNL AMI NIT) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15, OXA-48, NDM-1 | 3a | >106 |

| KPB941-14 | 2014 | Trachea | − | K27 | 833 | 7 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI SUL NIT) | SHV-11, TEM-1, OXA-48 | 2b | >106 |

| KPB591-15 | 2015 | Cerebrospinal fluid | − | K28 | 20 | 2 (BLA NIT) | SHV-11, OXA-48 | 3a | >106 |

| KPB54-14 | 2014 | Urine | − | K60 | NI | 7 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMK SUL NIT) | SHV-11, TEM-1, CTX-M-15 | 4a | >106 |

| KPB944-14 | 2014 | Urine | − | wzi420c | 147 | 6 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI NIT) | SHV-11, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 3a | >106 |

| KPB711-14 | 2014 | Wound | − | wzi420c | 147 | 6 (BLA TET QNL CHL AMI NIT) | SHV-11, CTX-M-15, OXA-48 | 0 | >106 |

The designations correspond to those presented in Table 2.

Reference strain for virulence in mice; ST – sequence type; NI – non identified.

Gene allele wzi420 is not associated with any known K-serotype in the Pasteur Institute Database; BLA – beta-lactams; TET – tetracyclines; QNL – quinolones; CHL – chloramphenicol; AMK – aminoglycosides; SUL – sulfonamides.

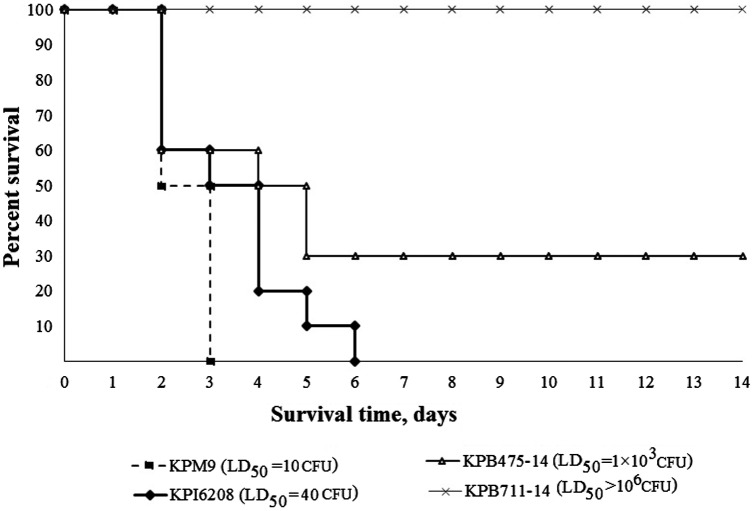

To compare in vivo virulence of the strains an experimental K. pneumoniae infection model on outbred white mice was used. Positive control for hypervirulence in mice K. pneumoniae strain KPM9 was attributed to capsular type K20 [13]. Thirty-seven clinical strains carrying different arrays of virulence genes and belonged to different K-types were selected. The strains were isolated from the respiratory system (n = 18), urine (n = 13), cerebrospinal fluid (n = 3) and wounds (n = 3) of the patients. According to the data obtained, the clinical strains were divided into three groups: hypervirulent (LD50 < 100 CFU), virulent (LD50 from 3 × 102 to 104 CFU) and non-virulent (LD50 > 106 CFU) in mice (Figure 2). It should be noted, virulent and hypervirulent in mice strains were isolated from the patients with severe infections of the central nervous system (meningitides), respiratory system (ventilator-associated pneumonia) or urinary tract catheter-associated infections. Five K. pneumoniae strains (KPB1103-14, KPB1802K, KPB2580-14, KPB4010, and KPS73) were associated with patient death.

Figure 2.

Kinetics of survival in intraperitoneally inoculated mice in infection dose of 1 × 104 CFU by K. pneumoniae strains: KPM9 – reference virulent for mice strain isolated from fresh water; KPI6208 – hypervirulent clinical strain; KPB475-14 – virulent clinical strain; KPB711-14 – non-virulent clinical strain.

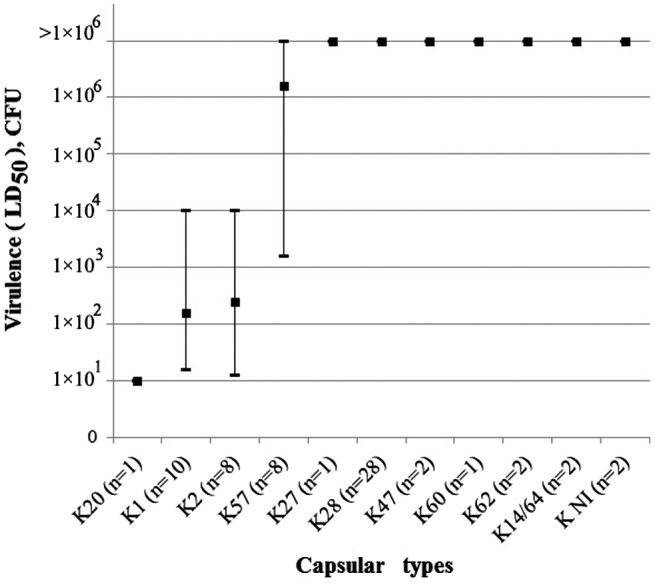

Strains of different capsular types exhibited different degrees of virulence in mice (Figure 3). All 10 virulent or hypervirulent in mice clinical strains of K1-type carried a complete array of selected 7 virulence genes: rmpA, aer, uge2, wabG, kfu, fimH, and allR. The strains of K2-type had 6 or 5 virulence genes – allR and kfu or rmpA genes were missed in their arrays. One virulent strain of K57-type carried 5 virulence genes: rmpA, aer, wabG, kfu, and fimH. Non-virulent strains carried fewer (0–4) virulence genes. In our opinion, the importance of genes for the manifestation of Klebsiella virulence decreases in the following order: aer, rmpA, allR, kfu, uge. This result concerning virulence in mice does not conflict with the conclusion concerning Klebsiella virulence for human [31].

Figure 3.

Virulence in mice for K. pneumoniae strains attributed to capsular types K1, K2, K20, K27, K28, K47, K57, K60, K62, K14/62 and non-identified capsular types (KNI).

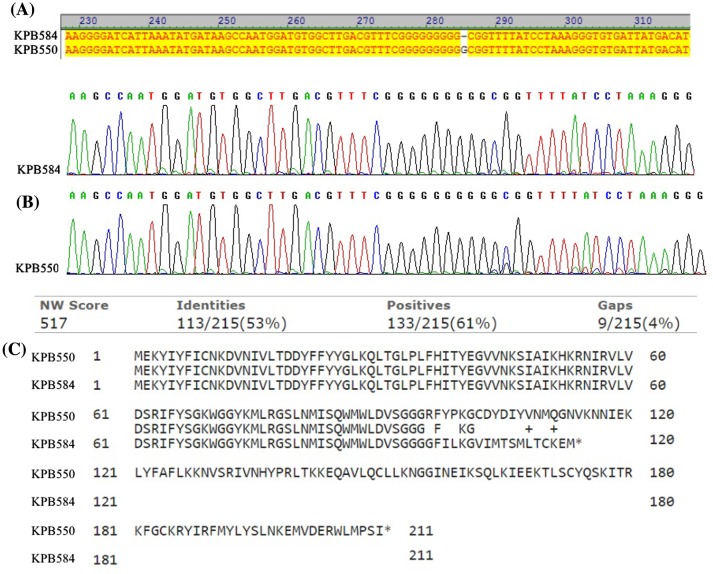

Two strains, K. pneumoniae KPB550 and KPB584, have the identical virulence gene profile (rmpA, aer, wabG, kfu, and fimH), and capsular type K57, but differ in the HV phenotype, resistance phenotype and the degree of virulence in mice. Sequencing of rmpA gene (in three replicates) revealed a deletion of one G nucleotide at the position 286 leading to a shift in the reading frame and generation of a stop codon in non-virulent K. pneumoniae strain KPB584 (Figure 4). This mutation apparently explains the absence of hypermucoviscosity and virulence in mice of this strain and confirms the importance of the rmpA gene for K. pneumoniae virulence. Another intrapersonal mutation of rmpA gene (insertion of one nucleotide at the polyG tract) was reported as a reason for negative hypermucoviscosity phenotype and low virulence of rmpA-positive K. pneumoniae isolates in 2015 [32].

Figure 4.

Comparison of rmpA gene sequences in K. pneumoniae strains KPB-584 and KPB-550. (A) Nucleotide alignment of the partial rmpA gene sequences; (B) Chromatogram of rmpA gene selected regions (C) Amino acid alignment of the gene translation products.

Sequence types and clonal complexes

Nine previously described sequence types (STs) of K. pneumoniae strains ST23 (n = 12), ST218 (n = 7), ST86 (n = 4), ST147 (n = 4), ST48 (n = 2), ST395 (n = 2), ST20 (n = 1), ST65 (n = 1), and ST833 (n = 1) were identified in this study. Moreover, novel ST2280 (n = 1) presenting a new allele profile of 7 housekeeping genes; and novel ST2174 (n = 1) carrying a novel allele of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene, gapA125 (GB KU510247) were first identified in this study (Table 3). The obtained sequence types were assigned to ten clonal complexes (CCs) based on the allelic identity of 6 housekeeping genes using eBURST software and the MLST PASTEUR database: CC23 (ST23 and ST218), CC65 (ST65 and ST2280), CC11 (ST833), CC14 (ST2174), CC15 (STNI), CC20 (ST20), CC48 (ST48), CC86 (ST86), CC147 (ST147), and CC395 (ST395) (Supplementary Figure 1). Sequence type ST1544 of reference virulent for mice strain K. pneumoniae KPM9 was not related to any CC presented in the database. CCs identified in this study were presented by 1030 K. pneumoniae strains in the MLST PASTEUR database on the date 1 September 2017. Among them, CC11 (40% of strains) contains the most globally distributed cKP strains; CC65 (16%) and CC23 (15%) include the most globally distributed hvKP strains (Supplementary Figure 2).

In our study, ‘classical’ CC11 was presented by one strain of ST833K27 (non-hypermucoviscous, non-virulent in mice, MDR). Moreover, strains of ST48K62, ST395K47, ST147K14, ST20K28, STNIK60 and ST147KNI (non-hypermucoviscous, non-virulent in mice) were attributed to this group of K. pneumoniae. ‘Hypervirulent’ CC65 was presented by two strains of ST65K2 and ST2280K2 (hypermucoviscous, hypervirulent in mice). The CC23 was more heterogenic – presented by 10 strains of ST23K1 (hypermucoviscous, virulent in mice); two strains of ST23K57 (non-hypermucoviscous, non-virulent in mice); one strain of ST218K57 (hypermucoid, virulent in mice); four strains of ST218K57 (hypermucoviscous, non-virulent in mice), two strains of ST218K57 (non-hypermucoviscous, non-virulent in mice). Moreover, four strains of ST86K2 (hypermucoviscous, virulent in mice) and one strain of ST2174K2 (hypermucoviscous, virulent in mice) were attributed to highly virulent K. pneumoniae (Table 3). Of particular interest are hypervirulent, ST23K1, blaCTX-M-15 and blaOXA-48-positive K. pneumoniae strain KPB2580-14 and four closely related, virulent in mice strains (KPB463K-13, KPB475-14, KPB594-14, and KPB1103-14). K. pneumoniae strain KPB2580-14 which is distinguished from others by its hypervirulence for humans and in mice, was selected for whole genome sequencing analysis.

Genome characteristic of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae of ST23 acquired pCTX-M-15 and pOXA-48 plasmids

As a result of K. pneumoniae strain KPB2580-14 whole genome sequencing 360 contigs were obtained, the total length of the genome was 5773846bp. The GenBank accession number is PUXF00000000.1. Raw data accession number is SRR6785071. Chromosomal fragment with putative iron transport and phosphotransferase function genes (20430bp) and the chromosomal region associated with allantoin metabolism (63291bp) were identified, as well as sequence type ST23 was confirmed.

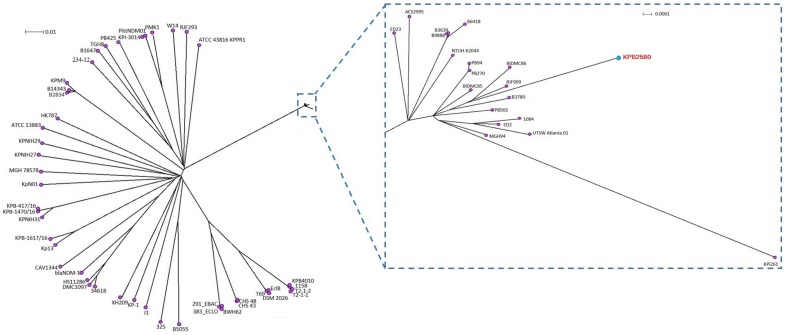

Phylogenetic analysis showed that the strain KPB2580 was clustered into the same clade with K1 type strains of clonal complex CC23 causing liver abscess such as 1084 [33], NTUH_K2044 [34], ED2 and ED23 [35] isolated in Taiwan. In addition, this group includes our previously isolated hypermucoviscous, multy-drug resistant strain KPi261 [13] and four hvKp strains B6418, B3639, B3789, and B9888 (isolate No. Kp2, Kp3, Kp4, and Kp5, respectively) that were isolated from community and hospital acquired bloodstream infection in India [36]. All these strains also belonged to the clonal complex CC23 and capsule type K1 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of 65 K. pneumoniae genomes based on the core single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) generated by the program Wombac 2.0. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joiningmethod with 1000 bootstrap resamplings. The genome of KPB2580 strain is highlighted in red.

Three plasmids were detected among KPB2580 contigs. The first was virulence plasmid homologous to pLVPK (GenBank: AY378100) carrying rmpA, iroN, iroD, iroC, iroB, fecI, fecA, rmpA2, iutA, iucD, iucC, and iucB genes (Supplementary Figure 3). The second was the plasmid homologous to pCTXM15 (GenBank: CP016925) carrying blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM-1 genes (Supplementary Figure 4). The third was the plasmid homologous to pOXA48 (GenBank: JN626286) carrying blaOXA-48 gene (Supplementary Figure 5).

Conclusions

Three groups of K. pneumoniae strains isolated in 2012–2016 were identified in this study: (i) cKP characterized by a high level of antibacterial resistance and avirulent in mice; (ii) hypermucoviscous, virulent in mice K. pneumoniae that are not multidrug resistant; (iii) hypermucoviscous, virulent in mice K. pneumoniae that are also multidrug resistant. This study is the first report about hvKP ST23K1 strain harboring extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15 and carbapenemase OXA-48 genes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation [grant number 15-15-00058]; K. pneumoniae strains were collected during the implementation of the Sectoral Scientific Program of the Rospotrebnadzor.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2018.1460949.

Supplementary Material

References

- [1].Bi W, Liu H, Dunstan RA, et al. . Extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae causing nosocomial bloodstream infections in china: molecular investigation of antibiotic resistance determinants, informing therapy, and clinical outcomes. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1230. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fazili T, Sharngoe C, Endy T, et al. . Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: an emerging disease. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351(3):297–304. 10.1016/j.amjms.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yan Q, Zhou M, Zou M, et al. . Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae induced ventilator-associated pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients in China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(3):387–396. 10.1007/s10096-015-2551-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wells JT, Lewis CR, Danner OK, et al. . Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess and metastatic endophthalmitis. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2015;4(1):2324709615624125. doi: 10.1177/2324709615624125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhao J, Chen J, Zhao M, et al. . Multilocus sequence types and virulence determinants of hypermucoviscosity-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from community-acquired infection cases in Harbin, North China. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2016;69(5):357–360. 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shon AS, Bajwa RP, Russo TA. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence. 2013;4:107–18. 10.4161/viru.22718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hennequin C, Robin F. Correlation between antimicrobial resistance and virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(3):333–341. 10.1007/s10096-015-2559-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cejas D, Fernández Canigia L, Rincón Cruz G, et al. . First isolate of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumonaie sequence type 23 from the Americas. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(9):3483–3485. 10.1128/JCM.00726-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Surgers L, Boyd A, Girard PM, et al. . ESBL-producing strain of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae K2, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(9):1687–1688. 10.3201/eid2209.160681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cheong HS, Chung DR, Park M, et al. . Emergence of an extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae ST23 strain from Asian countries. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(5):990–994. 10.1017/S0950268816003113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang R, Lin D, Chan EW, et al. . Emergence of Carbapenem-resistant serotype K1 hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;60(1):709–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hall JM, Ingram PR, O’Reilly LC, et al. . Temporal flux in beta-lactam resistance among Klebsiella pneumoniae in Western Australia. J Med Microbiol 2016;Mar 4. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kislichkina AA, Lev AI, Komisarova EV, et al. . Genome sequencing and comparative analysis of three hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated in Russia. Pathog Dis. 2017;75(4):ftx024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Finney DJ. Statistical method in biological assay. London: Charles Griffin; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nassrf X, Honoré N, Vasselon T, et al. . Positive control of colanic acid synthesis in Escherichia coli by rmpA and rmpB, two virulence-plasmid genes of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3(10):1349–1359. 10.1111/mmi.1989.3.issue-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Regué M, Hita B, Piqué N, et al. . A gene, uge, is essential for Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence. Infect Immun. 2004;72(1):54–61. 10.1128/IAI.72.1.54-61.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Izquierdo L, Coderch N, Piqué N, et al. . The Klebsiella pneumoniae wabG gene: role in biosynthesis of the core lipopolysaccharide and virulence. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(24):7213–7221. 10.1128/JB.185.24.7213-7221.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ma LC, Fang CT, Lee CZ, et al. . Genomic heterogeneity in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains is associated with primary pyogenic liver abscess and metastatic infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(1):117–128. 10.1086/jid.2005.192.issue-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yu WL, Ko WC, Cheng KC, et al. . Comparison of prevalence of virulence factors for Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses between isolates with capsular K1/K2 and non-K1/K2 serotypes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62(1):1–6. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chou HC, Lee CZ, Ma LC, et al. . Isolation of a chromosomal region of Klebsiella pneumoniae associated with allantoin metabolism and liver infection. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3783–3792. 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3783-3792.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fursova NK, Astashkin EI, Knyazeva AI, et al. . The spread of blaOXA-48 and blaOXA-244 carbapenemase genes among Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis and Enterobacter spp. isolated in Moscow, Russia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2015;14:46. 10.1186/s12941-015-0108-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Priamchuk SD, Fursova NK, Abaev IV, et al. . Genetic determinants of antibacterial resistance among nosocomial Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., and Enterobacter spp. isolates collected in Russia within 2003–2007. Antibiot Khimioter 2010;55(9–10):3–10 (Russian). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, et al. . Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):4178–4182. 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4178-4182.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:254–267. 10.1093/molbev/msj030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. . Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–281. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Volozhantsev NV, Kislichkina AA, Lev AI, et al. . Genome sequences of two NDM-1 Metallo-β-Lactamase-producing multidrug-resistant strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae with a high degree of similarity, one of which contains prophage. Genome Announc 2017;5(42):pii: e01173–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shabanova VV, Krasnova MV, Boshkova SA, et al. . The first case of the detection in Russia of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147, which produced NDM-1 carbapenemase. Traum and Orthop of Rus 2015;2(76):90–98(Russian). [Google Scholar]

- [29].Anastasia I. Lev, Evgeny I. Astashkin, Rima Z. Shaikhutdinova, Mikhail E. Platonov, Nikolay N. Kartsev, Nikolay V. Volozhantsev, Olga N. Ershova, Edward A. Svetoch, Nadezhda K. Fursova.. Identification of IS1R and IS10R elements inserted into ompk36 porin gene of two multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae hospital strains. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2017;364(10):fnx072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Paczosa MK, Mecsas J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80(3):629–661. 10.1128/MMBR.00078-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tan TY, Ong M, Cheng Y, et al. . Hypermucoviscosity, rmpA, and aerobactin are associated with community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremic isolates causing liver abscess in Singapore. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2017; Jul 14. pii: S1684-1182(17)30143-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yu WL, Lee MF, Chang MC, et al. . Intrapersonal mutation of rmpA and rmpA2: a reason for negative hypermucoviscosity phenotype and low virulence of rmpA-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2015;3(2):137–141. 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lin AC, Liao TL, Lin YC, et al. . Complete genome sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae 1084, a hypermucoviscosity-negative K1 clinical strain. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(22):6316. 10.1128/JB.01548-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Brisse S, Fevre C, Passet V, et al. . Virulent clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification and evolutionary scenario based on genomic and phenotypic characterization. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(3):e4982. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lin HH, Chen YS, Hsiao HW, et al. . Two genome sequences of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with sequence type 23 and capsular serotype K1. Genome Announc. 2016;4(5):e01097-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shankar C, Veeraraghavan B, Nabarro LEB, et al. . Whole genome analysis of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from community and hospital acquired bloodstream infection. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18:6. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.