Abstract

Immunoinformatics plays a pivotal role in vaccine design, immunodiagnostic development, and antibody production. In the past, antibody design and vaccine development depended exclusively on immunological experiments which are relatively expensive and time-consuming. However, recent advances in the field of immunological bioinformatics have provided feasible tools which can be used to lessen the time and cost required for vaccine and antibody development. This approach allows the selection of immunogenic regions from the pathogen genomes. The ideal regions could be developed as potential vaccine candidates to trigger protective immune responses in the hosts. At present, epitope-based vaccines are attractive concepts which have been successfully trailed to develop vaccines which target rapidly mutating pathogens. In this article, we provide an overview of the current progress of immunoinformatics and their applications in the vaccine design, immune system modeling and therapeutics.

Keywords: Antigen, bioinformatics, epitope prediction, human leukocyte antigen (HLA), major histocompability (MHC), immunoinformatics, in silico tools, reverse vaccinology, vaccine design

Introduction

The journey of vaccines development began in 1796 when Edward Jenner created the first vaccine to protect human against smallpox. His work became the foundation for the design and development of various vaccines against bacterial infections such as diphtheria, tetanus, anthrax, cholera, plague, typhoid and tuberculosis in the nineteenth century [1]. By the middle of the twentieth century, active vaccine research and development against viral infections like polio, measles, mumps, and rubella were reported [2–4]. Although effective microbial vaccines have been developed based on the conventional methods (Figure 1), they were still hindered by limitations in which: (i) not all pathogens can be grown in culture; (ii) some cell-associated microorganisms require specific and costly cell cultures; (iii) extensive safety procedure may be mandatory for personnel who handle live pathogens; (iv) insufficient killing or attenuation may result in the introduction of virulent organisms into the final vaccine and inadvertently cause disease and (v) time consuming [3,4]. Therefore, innovative techniques have been devised to design vaccines that are safe, more efficacious, and less expensive than traditional vaccines. Moreover, the expansion of vaccine targets against non-communicable diseases such as allergies and cancers has further attracted more vaccine enthusiasts. This review highlights the potential role of current computational-aided immunoinformatics approach in designing safe and effective vaccine.

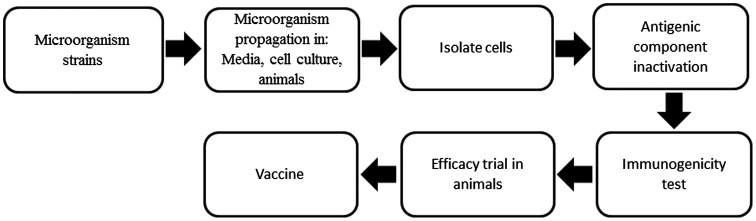

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the conventional approach to bacterial vaccine development.

Notes: The process for the development of bacterial vaccines using a conventional approach is based on pasture’s principle. According to this principle the microorganism is cultivated under laboratory conditions from which single components are isolated using biochemical, microbiological and serological methods. The antigenic protein produced from the bacterium is purified or inactivated, after which it is tested for its ability to induce an immune response. After immunogenicity testing the proteins are subjected for efficacy evaluation in animal models. If the trials show positive result, the proteins are subjected for further development. However although successful in many cases, this approach has several limitations. Such as this method can only be applicable to those microorganisms that can be cultivated under laboratory conditions. In many cases those antigens that are expressed during an infection may not be able to express under laboratory conditions. Apart from these limitations, developing vaccine through conventional method takes years to identify a protective and useful antigen.

in silico Approach

in silico approach enables computational methods to predict and design new vaccine components. Two promising in silico fields that have widely contributed to the development of vaccine are bioinformatics and immunoinformatics. Bioinformatics involves the convergence of several different disciplines to organize and store large amounts of biological information which are generated from experiments conducted in the field of genetics, molecular biology and biotechnology. It comprises various studies such as proteomics, genomics and vaccinomics. The information obtained from these disciplines has sped up the identification and characterization of new antigens.

Over the years, sequencing experiments have generated a large amount of data relevant to immunology research. With recent advancement in research methodologies, huge amounts of functional, clinical and epidemiologic data are being reported and deposited in various specialist repositories and clinical records [5]. Combining this accumulated information together can provide insights into the mechanisms of immune function and disease pathogenesis. Hence, the need to handle this rapidly growing immunological resource has given rise to the field known as immunoinformatics. The main objective of immunoinformatics is to convert large-scale immunological data, using a wide variety of computational, mathematical and statistical methods that range from text mining, information management, sequence analysis and molecular interactions to understand and organize these large-scale data to obtain immunologically meaningful interpretations. There are also attempts made for the extraction of interesting and complex patterns from non-structured text documents in the immunological domain, including categorization of allergen cross-reactivity information, identification of cancer-associated gene variants, and the classification of immune epitopes [6]. The tools used in this field are based on statistical and machine learning system and are used for studies in modeling molecular interaction. They also play a role in defining new hypothesis to understand the immune system mechanism [7]. Advanced knowledge in the field of infectious disease such as pathogenesis, virulence factor and the host immune response has overtaken the traditional method of vaccine development [4], leading to the development of second generation vaccines. The integration of the development in bioinformatics tools along with the advancement in recombinant DNA (rDNA) technologies will further enable the rise of third generation vaccines known as reverse vaccinology.

Many new databases and tools have been developed as accessible repository for the storage and analysis of huge immunology-associated biological data [8]. Most of these databases have been listed in the form of public repositories to facilitate researchers to search for a desired database. Three of the major public repositories that contain information about available databases and tools associated with immunoinformatics are (i) Nucleic Acids Research Database Annual Issue (ii) Canadian Bioinformatics Links Directory and (iii) Immune Epitope Database and Analysis Resource (IEDB). These public repositories provide access to up-to date annotated lists of immunoinformatics resources which ensure the quality and relevance of these databases and tools [8]. They contain articles associated with publications of new biological data repositories as well as providing major and updated changes from previously published databases. The Nucleic Acids Research Database Annual Issue also maintains the Molecular Biology Database Collection (MBDC) (http://www.oxfordjournals.org/nar/database/c), an online repository which describes all the published databases. The Canadian Bioinformatics Links Directory consists of contents that are directly extracted from those Nucleic Acids Research Database Annual Issue [8]. The contents in the Links Directory are contextually annotated and contain tags based on MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms to describe the resources. Annotation of these contents are a characteristic feature of the Link Directory which can be used for searching contents. Another important characteristic of the directory is curation of the contents, eliminating ‘dead’ contents and links that are no longer available. Yet, IEDB contains information on immune epitopes related to adaptive immune responses particularly for humans, primates, rodents, and other animal species. Since 2004, IEDB has manually curated approximately 16,000 published manuscripts. Curation of data is primarily focused on NIAID Category A, B, and C priority pathogens (including Influenza) and NIAID Emerging, Re-emerging infectious diseases. Experimental data associated with epitopes from other infectious agents, allergens and autoantigens are now freely and easily accessible to the scientific community via most web browsers as a web-based interface [9]. All these public repositories can guide researchers through the process of selecting database and tools of interest to facilitate the generation of new research approaches in the development of diagnostics and therapeutics for the future personalized medicine [8].

The reverse vaccinology approach coined by Rino Rappuoli was initially developed to identify potential pathogenic microbial vaccine based on genomic data [3,4]. Whole genomic sequence search, followed by computational analysis were performed to predict proteins that were most likely to be effective antigenic components. This approach is widely applicable as there are many genome sequences available publicly. In 2000, reverse vaccinology was initially applied for the development of vaccines against serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis [10]. The increase of new wealth genomic information subsequently led to the development of vaccines for antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumonia [11]. However, the lack of advanced software impeded this computational vaccinology approach in most research laboratories. Until 2008, a comprehensive program known as Vaxign was created by He and colleagues to facilitate the vaccine research through reverse vaccinology approach [12,13]. This program comprised of a computational pipeline that utilized bioinformatics technology to find potential genes from the genomes for developing vaccines. The program was developed to predict possible antibody targets based on various criteria by utilizing microbial genomic and protein groupings as data information [12]. The major predicted features included subcellular location of proteins, transmembrane domain, adhesion probability, sequence similarity to host proteome and MHC class I and II epitope binding. Among these features, subcellular localization was considered as one of the main criteria for target prediction [12,13]. This program was a part of web-based system called Vaccine Investigation and Online Information Network (VIOLIN, http://www.violinet.org). Vaxign has been widely used for the identification of vaccine targets against various pathogens including Brucella spp. [14,15], Acinetobacter baumannii [16] and Mycobacterium tuberculosis [17].

From genomics to epitope prediction

High throughput human leukocyte antigen (HLA) binding assay and Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) have led to major progress exclusively in epitope prediction tools development [7]. Basically, the immunogenicity of an antigen is associated with its ability to interface with the humoral (B-cell) and cellular (T-cell) immune systems. To fully characterize the immune response to antigens it is necessary to identify specific MHC/HLA-antigen interaction [18]. An immunogen construct containing both B- and T-cell epitopes is crucial to effectively induce strong immune responses when in contact with host immune system [19,20]. The progression from genomics to epitope prediction has led to the evolution of designing epitope-based vaccines. Epitopes hold huge potential for vaccine design, disease prevention, diagnosis and treatment and are therefore of particular interest to both clinical and basic biomedical researchers. With the advent of recombinant DNA (rDNA) technology, it is possible to isolate specific epitopes to replace the whole pathogen in a vaccine; and chimeric proteins (multi-epitope vaccines) can be designed to enhance a strong immune response. Designing highly efficient multi-target vaccine is not an easy process as proper identification of the immunogenic peptide is necessary in order to elicit an immune response [5,21]. In designing an ideal epitope-based vaccine, two factors should be considered: (i) the selected epitope for the vaccine is conserved across different stages of the pathogen and its variant and (ii) the desired immune response. All the above information associated with the design of epitope-based vaccine can be performed using immunoinformatics approach (Figure 2). Prediction can be done using various immunoinformatic and bioinformatics tools to determine the MHC (or HLA in human) binding capacity, which has proven to be the key component for identification of various epitopes [22]. Currently epitope-based antibodies are mostly adopted in bio-therapeutics products [21].

Figure 2.

Schematic workflow to vaccine development through reverse vaccinology.

Notes: The first phase employed in reverse vaccinology is dry lab analysis. Using computational tools and online databases a gene of interest is selected. The selected genomes are further analyzed to identify potential immunogenic epitopes (B-cells or T-cell) that can induce an immune response. Once the antigenic candidates are selected, they are proceeded to second phase (wet lab) for validation. In the latter phase, antigenic proteins or peptides of interest are produced or synthesized. The immunogenicity and the protective efficacy of the recombinant antigens are then tested in laboratory animal models. An appropriate vaccine formulation is assessed prior to the vaccine pre-clinical trials.

B-cell epitope prediction and tools

B-cell epitopes are defined as surface accessible clusters of amino acids that are recognized by secreted antibodies or B-cell receptors, which are able to elicit cellular or hormonal immune response [18]. Identification of B-cell epitopes plays an important role in development of epitope-based vaccines, therapeutic antibodies, and diagnostic tools. Surface immunoglobulins of B cells and antibodies recognize the B-cell epitope of an antigen in its native conformation. B-cell epitopes are either continuous (linear/sequential) or discontinuous (conformational). In general, B-cell epitopes bind to B-cell receptors (BCR) and the binding site of these receptors (BCR) are primarily hydrophobic, consisting of 6 hyper variable loops of varied lengths and amino acid composition [5,6,21,23]. Prediction of B-cell epitopes is primarily based on its amino acid properties such as hydrophilicity, the charged exposed surface area and secondary structure. It is estimated that about 85% of documented B-cell epitopes could be considered to be continuous in sequence, but it should be noted that not all residues within an epitope are functionally essential for binding, and this binding efficacy depends on the amino acid sequence such that, if a single amino acid is substituted or eliminated then the binding efficacy is reduced [5,6,24]. In contrast, in discontinuous B-cell epitopes the discontinuity is due to the fact that distant residues are brought into spatial proximity by protein folding. These complex structures of folded proteins lead to spatial proximity of amino acids that can be remote in the antigen sequence. Prediction of discontinuous B-cell epitope is difficult because of two reasons (i) not many prediction softwares are available for discontinuous B-cell epitopes and (ii) classical machine learning based system require a continuous sequenced data [7,21,23,25].

Selected specific web-based servers available for the prediction of continuous or discontinuous B-cell epitopes are listed in Table 1. These integrative B-cell prediction tools shed light on the identification of immunogenic B-cell epitopes which may trigger antibody response in the host immune system [5]. Among them, the BCPREDS server is a user-friendly computational tool that can be used for the identification and characterization of continuous B-cell epitopes from a protein sequence; these identified B-cell epitopes could be used for vaccine design, immunodiagnostic tests and antibody production. This server allows users to predict B-cell epitopes by uploading an antigenic sequence into the server, followed by selecting any of the three prediction methods: (i) AAP method [26]; (ii) BCPred [27]; (iii) FBCPred [28]. Similarly, ABCpred is another server that is used for the prediction of continuous B-cell epitope. This server makes use of artificial neural network to predict B-cell epitope. It was developed based on recurrent neural network using fixed length patterns with a 65.93% accuracy [29]. In addition, the SVMTriP server predicts continuous B-cell epitopes based on support vector machine algorithm (SVM) by combining the Tri-peptide similarity and propensity score (SVMTriP) with the aim to achieve better prediction [30].

Table 1.

List of servers used for the B-cell epitope prediction.

| Prediction tool | Types of prediction | Web address | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCPreds | Continuous B-cell epitopes | http://ailab.ist.psu.edu/bcpreds/predict.html | [26–28] |

| BepiPred | Continuous B-cell epitopes | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/BepiPred/ | [53] |

| ABCPred | Continuous B-cell epitopes | http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/abcpred/ | [29] |

| BcePred | Continuous B-cell epitopes | http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/bcepred/ | [54] |

| LBtope | Continuous B-cell epitope | http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/lbtlbt/ | [55] |

| SVMTrip | Continuous B-cell epitope | http://sysbio.unl.edu/SVMTriP/ | [30] |

| EPCES | Discontinuous B-cell epitope | http://sysbio.unl.edu/EPCES/ | [56] |

| DiscoTope | Discontinuous B-cell epitope | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/DiscoTope/ | [32] |

| BEPro (PEPITO) | Discontinuous B-cell epitope | http://pepito.proteomics.ics.uci.edu/ | [57] |

| Ellipro | Discontinuous B-cell epitope | http://tools.iedb.org/ellipro/ | [31] |

| CBTOPE | Discontinuous B-cell epitope | http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/cbtope/ | [33] |

| PEASE | Discontinuous B-cell epitope | http://www.ofranlab.org/PEASE | [58] |

| EpiPred | Discontinuous B-cell epitope | http://opig.stats.ox.ac.uk/webapps/sabdab-sabpred/EpiPred.php | [59] |

In the case of discontinuous B-cell epitope prediction, one of the servers used is ElliPro. This server predicts epitopes based on 3D structure of a protein antigen. It associates each predicted epitope with an average score from epitope residues and this score is known as protrusion index (PI). In the method, the 3D shape of the protein is approximated by a number of ellipsoids [31]. Similarly, DiscoTope is another server which predicts discontinuous B-cell epitopes from 3D structure of a protein. The method utilizes calculation surface accessibility and a novel epitope propensity amino acid score. The final scores are calculated by combining the propensity scores of residues in spatial proximity and the contact numbers [32]. CBTOPE is also an SVM-based predictor server which combines traditional features of physicochemical profiles and sequence-derived inputs. It outperformed other structure methods using binary profile of pattern and physicochemical profile of patterns with better sensitivity and AUC on the same benchmark dataset [33].

T-cell epitope prediction and tools

T-cell epitopes are parts of intracellular processing antigens that are presented to T lymphocytes in association with molecules of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Antigenic peptides bound with MHC are presented to T cell for immunity stimulation. Therefore identification of these MHC binding peptides is a central part of any algorithm that is used to predict T-cell epitopes [6]. T-cell epitopes are bound in a linear form to MHCs, the interface between ligands and T cells can be modeled with accuracy. These epitopes are linked together into the binding grove of MHC class I and class II molecules, through interactions between their R group side chain and pockets located on the floor of the MHC [5,34]. Based on this knowledge, a large number of computational tools have been established and used for identifying putative T-cell epitopes and MHC binding peptides (Table 2). The identification of these putative T-cell epitopes and MHC binding peptides is based on various algorithms such as artificial neural network (ANN), protein threading and docking techniques, hidden Markov model (HMM) and decision tree [23]. Among all the MHC I and MHC II binding predictor softwares, MHC class I predicators have displayed to be more efficient in their prediction with an estimated accuracy of 90–95%. In predicting MHC alleles, RANKPEP is one server which makes use of Position Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSMs) to predict peptide binders to MHC I and MHC II molecules from protein sequences. It is a friendly platform which offers a wide range of allelic coverage to MHC I and MHC II alleles for human and mouse. The algorithm used by this database is written in Python, and it sorts and stores all protein segments with the length of the PSSM width. The scoring starts at the beginning of each sequence and the PSSM are slid over the sequence one residue at a time until it reaches the end of the sequence. Furthermore, a threshold value is set in order to narrow down the potential binders from the list of ranked peptides; a binding threshold is defined as a score value that includes 90% of the peptides within the PSSM. This binding threshold value is built into each matrix, delineating the range of putative binders among the top scoring peptides [35,36].

Table 2.

List of servers used for the T-cell epitope prediction.

| Prediction tool | Types of prediction | Web address | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| EpiJen | MHC I | http://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/epijen/EpiJen/EpiJen.htm | [60] |

| nHLAPred | MHC I | http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/nhlapred/ | [61] |

| BIMAS | MHC I | https://www-bimas.cit.nih.gov/molbio/hla_bind/ | [62] |

| NetMHC | MHC I | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetMHC/ | [63] |

| Propred 1 | MHC I | http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/propred1/ | [64] |

| MMBPred | MHC I | http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/mmbpred/ | [65] |

| MHC2Pred | MHC II | http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/mhc2pred/ | [66] |

| Propred | MHC II | http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/propred/ | [39] |

| netMHCIIPan | MHC II | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetMHCIIpan/ | [67] |

| SYFPEITHI | Both MHC I & II | http://www.syfpeithi.de/bin/MHCServer.dll/EpitopePrediction.htm | [68] |

| MHCPred | Both MHC I & II | http://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/mhcpred/MHCPred/ | [69] |

| RANKPEP | Both MHC I & II | http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/rankpep.html | [35] |

| SVRMHC | Both MHC I & II | http://us.accurascience.com/SVRMHCdb/ | [70] |

| IEDB | Both MHC I & II | http://www.iedb.org | [9] |

Kernel-based Inter-allele peptide binding prediction system (KISS), predicts if a 9-mer peptide will bind to a MHC I molecule of 64 alleles using a support vector machine (SVM) multitask kernel to leverage the available training information across the alleles, which improves it accuracy especially for the alleles with few known epitopes [37]. The predictor is trained on databases which contain known epitopes from SYFPEITHI, MHCBN and IEDB databases. There are many servers available for the identification of MHC I binding predictors, the most complete servers in terms of allelic coverage and identification of alleles were as mentioned above. These servers can also identify alleles in other organism besides humans.

Though MHC class I prediction seems to have achieved a good success, it is not the same for MHC class II. MHC Class II prediction has achieved a very limited success in predicting the potential binding epitopes. This is mainly because of the low the predicting accuracy. Several factors that contributed to low accuracy include insufficient or low quality training data, difficulty in identifying 9-mer binding cores within longer peptides used for training and lack of consideration of the influence of flanking residues and the relative permissiveness of the binding groove of MHC II molecules, which limit the binding stringency. For instance, Propred is a server used for the prediction of MHC Class II binding regions present in an antigen sequence using quantitative matrices. The server implement matrix-based prediction algorithm, employing amino-acid/position coefficient table deduced from literature. This server assists in locating promiscuous binding regions that are useful in selecting vaccine candidates that can bind to 51 HLA-DR alleles [38,39].

Future Prospect of Immunoinformatics in Therapeutic Applications

The advances in immunoinformatics technology have changed the face of current medical research. Currently, this technology has widely been used for the evaluation of epitopes for constructing chimeric multi-epitope vaccine for various organisms including Hepatitis B Virus [40] or Escherichia coli [41], Dengue [42], Schistosoma haematobium [43], Treponema pallidum [44], Staphylococcus aureus [45] and Trypanosoma cruzi [46]. The feasibility and low cost enable the mapping of B- and T-cell epitopes of A-C pathogens that are available at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) such as Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), Clostridium botulinum toxin (botulism), Variola major (small pox), rabies and influenza viruses. This technology is envisaged to play a more prominent and effective role in infection control and health care epidemiology of the deadly pathogens. Table 3 illustrates some successful studies conducted using in silico techniques for the development of a vaccine [23,47].

Table 3.

Studies performed using in silico techniques to predict potential vaccine candidates.

| Type | Organism | Immunoinformatics tool | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite | Schistosoma haematobium | Bepipred, RankPep | [43] |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | IEDB MHC Tools | [46] | |

| Bacteria | Staphylococcus aureus | Bcepred, Discotope | [45] |

| Enterotoxigenic E. coli, enterohemorragic E. coli and Shigella | BCPred, Discotope, ElliPro, VaxiJen, SYFPEITHI, ProPred, | [71] | |

| Escherichia coli | BepiPred, ABCpred, DiscoTope, SYFPEITHI, VaxiJen, Algpred | [41] | |

| Treponema pallidum | Vaxign | [44] | |

| Virus | Ebola virus (EBOV) | VaxiJen, NetCTL, IEDB, AllerHunter | [72] |

| Hepatitis B | IEDB MHC Tools, MHC-NP, netCTLpan, RANKPEP, and netMHCpan, ToxinPred, NetMHC | [40] | |

| Cancer | Human papillomavirus (HPV)-caused cervical cancer | NetMHC 4.0, IEDB MHC Tools, CTLPred, PAComplex, NetMHCIIpan 3.1, RANKPEP, TepiTool, MHCPred V.2.0, LBtope, EPMLR, BCPREDS, and BepiPred 1.0b, IFNepitope, Allerdictor | [73] |

| Breast cancer | ABCpred | [74] |

Apart from epitope-based vaccine research, immunoinformatics technology has also been employed in various fields of medical science research including cancer study, infectious disease and allergy, and personalized medicine. For instance, cancer informatics tools such as COSMIC (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), canEvolve (http://www.canevolve.org/AnalysisResults/AnalysisResults.html), CGWB (https://cgwb.nci.nih.gov/) are developed to diagnose the cancerous disease prior to therapy. Cancer progression is a form of somatic evolution wherein a mutation provides an advantage to the cancer cells to grow continuously. Cancer informatics approach can rapidly screen for potential antigens and design specific types of immunotherapy for the disease. However, it is still difficult to find the set of antigens that varies between different tumors, but with informatics tool, it is possible to classify tumors into subtypes which make it possible for the selection of therapeutic approaches [6,23]. One of such pipelines that can be used for this approach is pVAC-Seq. This method can be used to identify tumor-specific mutant peptides (neoantigens) which can elicit anti-tumor T-cell immunity. This database can be used as a checkpoint therapy response and identify targets for vaccine and adoptive T-cell therapies. This automated pipeline requires the input of several data such as a list of non-synonymous mutation identified by a somatic variant – called pipeline, which has been annotated with amino acid changes and transcript sequences. Finally, it requires the HLA haplotypes of patient derived through in silico approaches. With all the data in-hand, the pVAC-Seq implements three steps: (i) epitope prediction, (ii) integrating sequencing based information and (iii) filtering neoantigen candidates [48]. Another such server that can be used for neo-epitope and epitope prediction is the EpiToolKit. This server also provides an array of immunoinfomatic tools for MHC genotyping, epitope selection and epitope assembly for vaccine design. The tools from this server generate two outputs: (i) an interactive presentation of the result as html and (ii) an internal representation that can be used as input to other tools. This server also provides an access to a collection of epitope prediction tools such as SYFPEITHI, BIMAS, SVMHC and UniTope [49], allowing it to be used as a feasible tool for rational vaccine design [50].

Immunoinformatics approach can also be used to determine the allerginicity and allergic cross-reactivity of protein as well as genetically modified food crops. Currently, allergic informatics focuses on quality data management, T- and B-cell epitope predictions, allergic assessment and allergic cross reactivity. Guidelines have been proposed by World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for evaluating allerginicity of genetically modified food. AlgPred [51], and ALLERMATCH [52] are among the servers that have been used for allergen prediction [6,23].

This approach can also be used for the surveillance, modeling and response to an infectious disease. With the aid from mathematical modeling, pattern recognition and aberration detection, it is now possible to screen genetic repertoire and metabolic profiles of a pathogen and enhance recognition of disease outbreak patterns which play a crucial role in monitoring and evaluating control strategies. By integrating genomics and proteomics with bioinformatics strategies, a new approach will be materialized to target validation that can help in deciphering human immune responses to various pathogens in the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

Immunoinformatics is an emerging sub-discipline of bioinformatics. The advent of genome sequencing and immunological assays has tremendously improved the biological data in the scientific literatures. The progress in computational methods comprise a variety of statistical and machine learning algorithms, are now available for the discovery of promising immunogenic B-cell and T-cell epitopes bound to various HLA/MHC in the immunological databases. This has revolutionized new strategies for translational applications of epitope prediction, such as epitope-based design of prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines and antibody development. More importantly, computational tools could accelerate the process required for epitope screening, allowing researchers to focus on the most crucial vaccine and antibody design and development while minimizing the often-costly laboratory works. In tandem with the ability to perform rational antigen modification, immunoinformatics would help in designing therapeutics which is effective for many deadly diseases in the world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by The Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education of the Higher Institutions Centre of Excellence Program [grant number 311/CIPPM/4401005]; and Fundamental Research Grant Scheme [grant number 203/CIPPM/6171199].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mridula M and Kiran Shenoy for their comments on the manuscript.

References

- [1].Riedel S. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2005;18(1):21–25. 10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Serruto D, Rappuoli R. Post-genomic vaccine development. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(12):2985–2992. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bambini S, Rappuoli R. The use of genomics in microbial vaccine development. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14(5–6):252–260. 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Movahedi AR, Hampson DJ. New ways to identify novel bacterial antigens for vaccine development. Vet Microbiol. 2008;131(1–2):1–13. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Soria-Guerra RE, Nieto-Gomez R, Govea-Alonso DO, et al. An overview of bioinformatics tools for epitope prediction: implications on vaccine development. J Biomed Inform. 2015;53:405–414. 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tomar N, De RK. Immunoinformatics: a brief review. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1184:23–55. 10.1007/978-1-4939-1115-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Backert L, Kohlbacher O. Immunoinformatics and epitope prediction in the age of genomic medicine. Genome Med. 2015;7:119. 10.1186/s13073-015-0245-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lopez-Campos G, Bermejo-Martin JF, Almansa R, et al. Immunoinformatics and systems biology in personalized medicine. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1184:457–475. 10.1007/978-1-4939-1115-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vita R, Overton JA, Greenbaum JA, et al. The immune epitope database (IEDB) 3.0. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D405–D412. 10.1093/nar/gku938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rappuoli R. Reverse vaccinology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3(5):445–450. 10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00119-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sette A, Rappuoli R. Reverse vaccinology: developing vaccines in the era of genomics. Immunity. 2010;33(4):530–541. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].He Y, Xiang Z, Mobley HL. Vaxign: the first web-based vaccine design program for reverse vaccinology and applications for vaccine development. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:297505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Xiang Z, He Y. Genome-wide prediction of vaccine targets for human herpes simplex viruses using Vaxign reverse vaccinology. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14(Suppl 4):S2. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-S4-S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].He Y. Analyses of Brucella pathogenesis, host immunity, and vaccine targets using systems biology and bioinformatics. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gomez G, Pei J, Mwangi W, et al. Immunogenic and invasive properties of Brucella melitensis 16M outer membrane protein vaccine candidates identified via a reverse vaccinology approach. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59751. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Garg N, Singh R, Shukla G, et al. Immunoprotective potential of in silico predicted Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane nuclease, NucAb. Int J Med Microbiol. 2016;306(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hossain MS, Azad AK, Chowdhury PA, et al. Computational identification and characterization of a promiscuous T-cell epitope on the extracellular protein 85B of mycobacterium spp. for peptide-based subunit vaccine design. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:4826030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Paul S, Dillon MBC, Arlehamn CSL, et al. A population response analysis approach to assign class II HLA-epitope restrictions. J Immunol. 2015;194(12):6164–6176. 10.4049/jimmunol.1403074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].He Y, Rappuoli R, De Groot AS, et al. Emerging vaccine informatics. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:218590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moise L, Cousens L, Fueyo J, et al. Harnessing the power of genomics and immunoinformatics to produce improved vaccines. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2011;6(1):9–15. 10.1517/17460441.2011.534454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Potocnakova L, Bhide M, Pulzova LB. An introduction to B-cell epitope mapping and in silico epitope prediction. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:6760830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Paul S, Lindestam Arlehamn CS, Scriba TJ, et al. Development and validation of a broad scheme for prediction of HLA class II restricted T cell epitopes. J Immunol Methods. 2015;422:28–34. 10.1016/j.jim.2015.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tong JC, Ren EC. Immunoinformatics: current trends and future directions. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14(13–14):684–689. 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kringelum JV, Nielsen M, Padkjær SB, et al. Structural analysis of B-cell epitopes in antibody: protein complexes. Mol Immunol. 2013;53(1–2):24–34. 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Saha S, Bhasin M, Raghava GP. Bcipep: a database of B-cell epitopes. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:79. 10.1186/1471-2164-6-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chen J, Liu H, Yang J, et al. Prediction of linear B-cell epitopes using amino acid pair antigenicity scale. Amino Acids. 2007;33(3):423–428. 10.1007/s00726-006-0485-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].El-Manzalawy Y, Dobbs D, Honavar V. Predicting flexible length linear B-cell epitopes. Comput Syst Bioinformatics Conf. 2008;7:121–132. 10.1142/p585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].EL-Manzalawy Y, Dobbs D, Honavar V. Predicting linear B-cell epitopes using string kernels. J Mol Recognit. 2008;21(4):243–255. 10.1002/jmr.v21:4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Saha S, Raghava GP. Prediction of continuous B-cell epitopes in an antigen using recurrent neural network. Proteins. 2006;65(1):40–48. 10.1002/prot.21078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yao B, Zhang L, Liang S, et al. SVMTriP: a method to predict antigenic epitopes using support vector machine to integrate tri-peptide similarity and propensity. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45152. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ponomarenko J, Bui HH, Li W, et al. ElliPro: a new structure-based tool for the prediction of antibody epitopes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:514. 10.1186/1471-2105-9-514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kringelum JV, Lundegaard C, Lund O, et al. Reliable B cell epitope predictions: impacts of method development and improved benchmarking. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(12):e1002829. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ansari HR, Raghava GP. Identification of conformational B-cell Epitopes in an antigen from its primary sequence. Immunome Res. 2010;6:6. 10.1186/1745-7580-6-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. The discovery of MHC restriction. Immunol Today. 1997;18(1):14–17. 10.1016/S0167-5699(97)80008-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Reche PA, Glutting JP, Zhang H, et al. Enhancement to the RANKPEP resource for the prediction of peptide binding to MHC molecules using profiles. Immunogenetics. 2004;56(6):405–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Reche PA, Glutting JP, Reinherz EL. Prediction of MHC class I binding peptides using profile motifs. Hum Immunol. 2002;63(9):701–709. 10.1016/S0198-8859(02)00432-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jacob L, Vert JP. Efficient peptide-MHC-I binding prediction for alleles with few known binders. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(3):358–366. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sturniolo T, Bono E, Ding J, et al. Generation of tissue-specific and promiscuous HLA ligand databases using DNA microarrays and virtual HLA class II matrices. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(6):555–561. 10.1038/9858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Singh H, Raghava GP. ProPred: prediction of HLA-DR binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(12):1236–1237. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zheng J, Lin X, Wang X, et al. In silico analysis of epitope-based vaccine candidates against hepatitis B virus polymerase protein. Viruses. 2017;9(5):112. 10.3390/v9050112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zeinalzadeh N, Salmanian AH, Ahangari G, et al. Design and characterization of a chimeric multiepitope construct containing CfaB, heat-stable toxoid, CssA, CssB, and heat-labile toxin subunit B of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: a bioinformatic approach. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2014;61(5):517–527. 10.1002/bab.2014.61.issue-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Osorio JE, Partidos CD, Wallace D, et al. Development of a recombinant, chimeric tetravalent dengue vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 2015;33(50):7112–7120. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gomase VSCNR, Changbhale SS, Sherkhane AS, et al. in silico approach for prediction of vaccine potential antigenic peptides from 23-kda transmembrane antigen protein of Schistosoma haematobium. Int J Bioinform Res. 2012;4(3):276–281. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kumar Jaiswal A, Tiwari S, Jamal SB, et al. An in silico identification of common putative vaccine candidates against treponema pallidum: a reverse vaccinology and subtractive genomics based approach. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):402. 10.3390/ijms18020402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Delfani S, Imani Fooladi AA, Mobarez AM, et al. In silico analysis for identifying potential vaccine candidates against Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2015;4(1):99–106. 10.7774/cevr.2015.4.1.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nakayasu ES, Sobreira TJ, Torres R Jr, et al. Improved proteomic approach for the discovery of potential vaccine targets in Trypanosoma cruzi. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(1):237–246. 10.1021/pr200806s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sintchenko V, Anthony S, Phan XH, et al. A PubMed-wide associational study of infectious diseases. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9535. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hundal J, Carreno BM, Petti AA, et al. pVAC-Seq: a genome-guided in silico approach to identifying tumor neoantigens. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):11. 10.1186/s13073-016-0264-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Toussaint NC, Kohlbacher O. Towards in silico design of epitope-based vaccines. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2009;4(10):1047–1060. 10.1517/17460440903242283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Schubert B, Brachvogel HP, Jurges C, et al. EpiToolKit – a web-based workbench for vaccine design. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(13):2211–2213. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Saha S, Raghava GP. AlgPred: prediction of allergenic proteins and mapping of IgE epitopes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W202–W209. 10.1093/nar/gkl343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Fiers MW, Kleter GA, Nijland H, et al. Allermatch, a webtool for the prediction of potential allergenicity according to current FAO/WHO Codex alimentarius guidelines. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:133. 10.1186/1471-2105-5-133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Jespersen MC, Peters B, Nielsen M, et al. BepiPred-2.0: improving sequence-based B-cell epitope prediction using conformational epitopes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W24–W29. 10.1093/nar/gkx346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Saha SaR GPS. editor BcePred: Prediction of continuous B-cell epitopes in antigenic sequences using physico-chemical properties2004. Catania Sicily, Italy: Artificial Immune Systems: Third international conference, ICARIS; 2004. Sep 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Singh H, Ansari HR, Raghava GP. Improved method for linear B-cell epitope prediction using antigen’s primary sequence. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62216. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Liang S, Liu S, Zhang C, et al. A simple reference state makes a significant improvement in near-native selections from structurally refined docking decoys. Proteins. 2007;69(2):244–253. 10.1002/prot.v69:2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sweredoski MJ, Baldi P. PEPITO: improved discontinuous B-cell epitope prediction using multiple distance thresholds and half sphere exposure. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(12):1459–1460. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sela-Culang I, Benhnia MR, Matho MH, et al. Using a combined computational-experimental approach to predict antibody-specific B cell epitopes. Structure. 2014;22(4):646–657. 10.1016/j.str.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Krawczyk K, Liu X, Baker T, et al. Improving B-cell epitope prediction and its application to global antibody-antigen docking. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(16):2288–2294. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Doytchinova IA, Guan P, Flower DR. EpiJen: a server for multistep T cell epitope prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:131. 10.1186/1471-2105-7-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bhasin M, Raghava GP. A hybrid approach for predicting promiscuous MHC class I restricted T cell epitopes. J Biosci. 2007;32(1):31–42. 10.1007/s12038-007-0004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Coligan JE. Scheme for ranking potential HLA-A2 binding peptides based on independent binding of individual peptide side-chains. J Immunol. 1994;152(1):163–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Worning P, et al. Reliable prediction of T-cell epitopes using neural networks with novel sequence representations. Protein Sci. 2003;12(5):1007–1017. 10.1110/(ISSN)1469-896X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Singh H, Raghava GP. ProPred1: prediction of promiscuous MHC Class-I binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(8):1009–1014. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Bhasin M, Raghava GP. Prediction of promiscuous and high-affinity mutated MHC binders. Hybrid Hybridomics. 2003;22(4):229–234. 10.1089/153685903322328956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kaur H, Raghava GP. Prediction of beta-turns in proteins from multiple alignment using neural network. Protein Sci. 2003;12(3):627–634. 10.1110/ps.0228903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Andreatta M, Karosiene E, Rasmussen M, et al. Accurate pan-specific prediction of peptide-MHC class II binding affinity with improved binding core identification. Immunogenetics. 2015;67(11–12):641–650. 10.1007/s00251-015-0873-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Rammensee H, Bachmann J, Emmerich NP, et al. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50(3–4):213–219. 10.1007/s002510050595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Guan P, Doytchinova IA, Zygouri C, et al. MHCPred: a server for quantitative prediction of peptide-MHC binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3621–3624. 10.1093/nar/gkg510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wan J, Liu W, Xu Q, et al. SVRMHC prediction server for MHC-binding peptides. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:463. 10.1186/1471-2105-7-463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Hajizade A, Ebrahimi F, Amani J, et al. Design and in silico analysis of pentavalent chimeric antigen against three enteropathogenic bacteria: enterotoxigenic E. coli, enterohemorragic E. coli and Shigella. Biosci Biotech Res Comm. 2016;9(2):225–239. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Dash R, Das R, Junaid M, et al. In silico-based vaccine design against Ebola virus glycoprotein. Adv Appl Bioinform Chem. 2017;10:11–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Negahdaripour M, Eslami M, Nezafat N, et al. A novel HPV prophylactic peptide vaccine, designed by immunoinformatics and structural vaccinology approaches. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;54:402–416. 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Wiwanitkit V. Predicted B-cell epitopes of HER-2 oncoprotein by a bioinformatics method: a clue for breast cancer vaccine development. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8(1):137–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]