Abstract

Objectives:

To compare the efficacy of IV phenytoin and IV levetiracetam in acute seizures.

Design:

Randomized controlled trial.

Setting:

Tertiary care hospital, November 2012 to April 2014.

Patients:

100 children aged 3–12 yrs of age presenting with acute seizures.

Intervention:

Participants randomly received either IV phenytoin 20 mg/kg (n = 50) or IV levetiracetam 30 mg/kg (n = 50). Patients who were had seizures at presentation received IV diazepam prior to these drugs.

Outcome Measures:

Primary: Absence of seizure activity within next 24 hrs.

Secondary: Stopping of clinical seizure activity within 20 mins of first intervention, change in cardiorespiratory parameters, and achievement of therapeutic drug levels.

Results:

Two groups were comparable in patient characteristics and seizure type (P > 0.05). Of the 100 children, 3 in levetiracetam and 2 in phenytoin group had a repeat seizure in 24 hrs, efficacy was comparable (94% vs 96%, P > 0.05). Of these, 18 (36%) in phenytoin and 12 (24%) in levetiracetam group received diazepam. Sedation time was 178.80 ±97.534 mins in phenytoin and 145.50 ±105.208 mins in levetiracetam group (P = 0.346). Changes in cardiorespiratory parameters were similar in both groups except a lower diastolic blood pressure with phenytoin (P = 0.023). Therapeutic drug levels were achieved in 38 (76%) children both at 4 and 24 hrs with phenytoin, compared to 50 (100%) and 48 (98%) at 1 and 24 hrs with levetiracetam (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Intravenous levetiracetam and phenytoin have similar efficacy in preventing seizure recurrences for 24 hrs in children 3–12 years presenting with acute seizures.

KEYWORDS: Children, drug levels, levetiracetam, phenytoin, seizures

INTRODUCTION

Epilepsy is common in children, prevalence being 50–100/100,000.[1] Long-term antiepileptic treatment is indicated in all patients presenting with focal seizure and second episode of generalized tonic clonic seizure (GTCS). Long-term antiepileptic drug (AED) usually used are phenytoin, carbamazepine, or valproate.[2,3] Intravenous levetiracetam has been shown to be safe and effective in treating adults and children with convulsive and non-convulsive status epilepticus. It has been used in an acute seizure in a dose of 20–60 mg/kg in children,[4,5,6,7,8,9,10] though none of these are randomized controlled trials. In treatment protocols for status epilepticus, a role of valproate and levetiracetam is being evaluated after phenytoin.[11,12,13,14] Levetiracetam is being increasingly used as a first-line drug in partial seizures in adults.[15] IV loading is required for rapid achievement of appropriate drug levels. Hence, we compared efficacy and safety of IV levetiracetam with IV phenytoin in terms of seizure control and side effects in acute childhood seizures.

METHODS

A total of 100 children 3–12 years presenting to the pediatric emergency with focal motor seizures and second episode of generalized seizures were included in the study. Approval was taken from the Institutional Ethics Committee and a written informed consent was taken from parents or guardians. A sample size of 50 children in each group was decided as no similar trial was available at the time of protocol formulation, hence, a pilot study. The trial was registered with Indian Council of Medical Research with trial no.CTRI/2014/01/004297. Children already on antiepileptic medication, clinical evidence of meningitis and sepsis, acute head trauma, febrile seizure, congenital anomalies, and developmental delay were excluded as the underlying etiology of seizures makes them more resistant to anticonvulsant response. Group allocation was done by sealed envelope technique. Numbers 1 to 100 were randomized equally in two groups using a computer- generated process using urn method. These were used to create sealed envelopes numbered 1 to 100 each containing a slip of either phenytoin or levetiracetam.

After taking care of airway, breathing, an IV access was established and blood samples obtained to measure blood glucose, blood urea, serum electrolytes, and liver enzymes. Children who came convulsing to the emergency were given IV diazepam (0.3 mg/kg). Subjects were randomized to receive either IV levetiracetam (30 mg/kg at5 mg/kg/min) or IV phenytoin (20 mg/kg at 1 mg/kg/min) intravenously. As per protocol if seizures recurred on the first loading of the drug a further second loading of the same drug was given. If seizures still recurred the patients were loaded with another drug and were excluded from the study.

A detailed history regarding the type of seizures, any previous drug intake, history suggestive of meningitis and head trauma, and relevant family history were recorded in the case record form. Blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, level of consciousness (Glasgow coma scale), and convulsive activity were recorded every 15 min for the first 1 hr after the intervention began, then hourly for 3 hrs, then 4 hourly till completion of 24-hr study period. The children were monitored to see if there is any recurrence of seizure in the subsequent 24 hrs.

Three milliliter of venous sample were taken for measuring drug levels of levetiracetam at 1 hr and 24 hrs and for phenytoin at 4 hrs and 24 hrs after IV drug loading as per their pharmacokinetic profile. Serum was separated and stored at -80⁰C till it was analyzed. Levels for both the drugs were measured on an autoanalyzer by the enzyme immunoassay method. Levetiracetam levels were measured using ARK levetiracetam assay and phenytoin levels by the CEDIA phenytoin II assay. The minimum detectable concentration by the CEDIA phenytoin II assay was 0.6 mcg/ml and ARK levetiracetam assay was 2 mcg/ml. Measurement of either drug level resulted in <10% cross-reactivity in the presence of other drugs as specified by the assay. Therapeutic drug levels of phenytoin were 10–20 mg/dl and levetiracetam were 6–45 mg/dl as per laboratory and kit specifications.

Subsequently, patients continued to receive a maintenance dose of their drug, i.e., 40 mg/kg/day of levetiracetam and 5 mg/kg/day of phenytoin, intravenously, for 24 hrs followed by oral medication. At discharge from the hospital, the caregiver’s perception about the treatment was recorded, and appropriate treatment with oral AEDs was continued. The children were also followed up for 7 days for recurrence of seizure. Neuroimaging and EEG were advised in all patients. Other investigations for etiological diagnosis were carried out as and when required.

The primary outcome measure was absence of seizures for 24 hours. Secondary outcome variables included changes in respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation at various time points in the two groups and achievement of therapeutic drug levels.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Baseline characteristics and parameters in the two groups were compared by the Chi-square test for qualitative variables and unpaired t-test for quantitative variables. Muchly’s test of sphericity was applied for an intragroup variation in parameters up to one hour of drug administration. If found significant repeated measures analysis of variance was applied with Green House Geisser adjustment. Intergroup comparison of parameters was done by repeated measures analysis of variance. P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

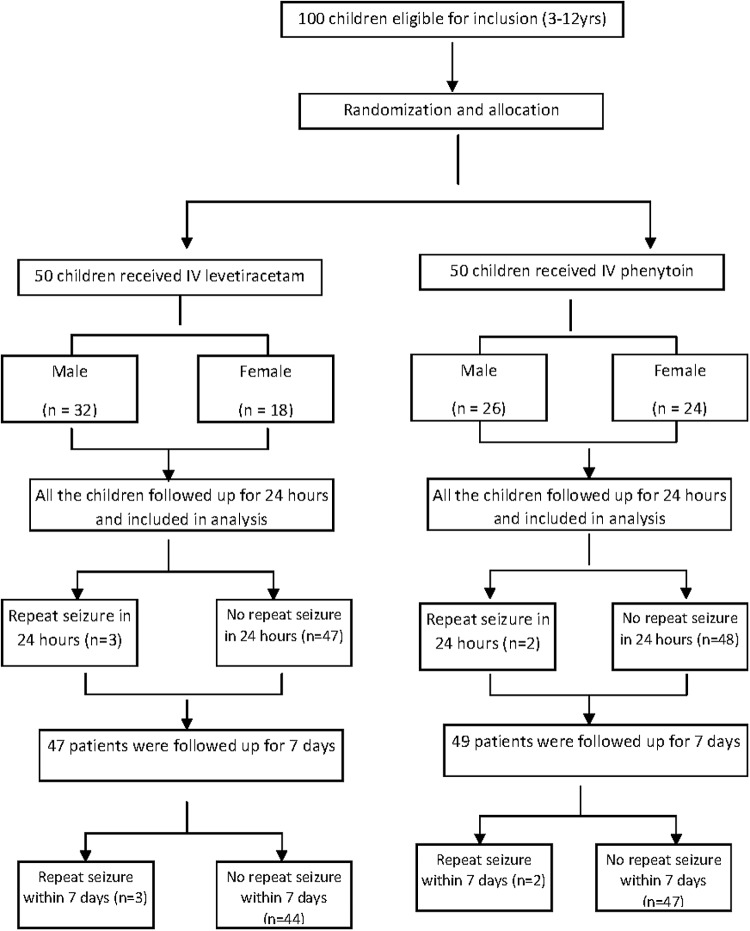

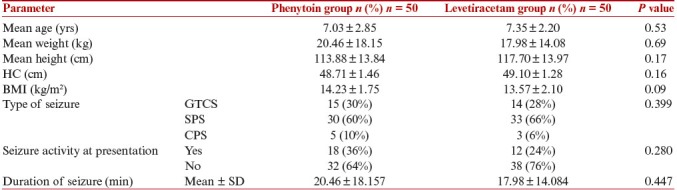

In this study, 100 children aged 3–12 yrs were randomized into two groups to receive either IV phenytoin or IV levetiracetam [Figure 1]. The two groups were comparable in terms of baseline characteristics, including age, anthropometry, clinical and laboratory parameters, and type of seizure [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Flow chart depicting the inclusion and follow up of study subjects

Table 1.

Comparison of anthropometry and seizure profile of study subjects

Eighteen (36%) children had seizure activity at a presentation in levetiracetam and 12 (24%) children in phenytoin group. They received diazepam before loading dose of phenytoin or levetiracetam. The seizure was aborted in all children and time to stop seizure was 30.83 ± 19.168 sec (range: 10–60 sec) in levetiracetam group and 27.78 ± 10.463 second (range: 15–60 second) in phenytoin group (P = 0.557).

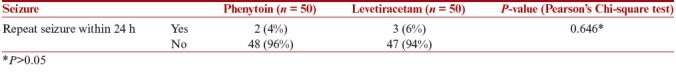

Primary outcome measure i.e. recurrence of seizure activity within 24 hr was seen in 3 children in levetiracetam group and 2 children in phenytoin group (P = 0.646). The overall success rate of therapy in terms of efficacy was 96% in phenytoin group and 94% in levetiracetam group (P = 0.646, Table 2).

Table 2.

Primary outcome of study subjects

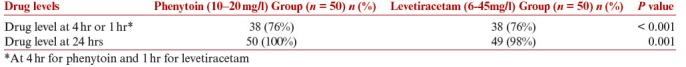

Levetiracetam levels were 22.45 ± 7.99 mg/l at 1 hr and 15.64 ± 5.72 mg/l at 24 hrs. All 50 (100%) children at 1 hr and 49 (98%) children at 24 hr achieved therapeutic levels (6–45 mg/l). Phenytoin levels were 17.91 ± 3.79 mg/l at 4 hrs and 15.67 ± 4.61 mg/l at 24 hrs. Thirty eight (76%) patients were in the therapeutic range at 4 and 24 hrs in the phenytoin group. The number of children with drug levels within therapeutic levels was significantly more in the levetiracetam group (P < 0.05) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of therapeutic drug levels in study subjects

Mean sedation time was 178.80 ± 97.534 min in phenytoin and 145.50 ± 105.208 min in levetiracetam group (P = 0.346). Sedation time varied from 45 to 480 min in both the groups. Mean sedation time was 151.87 ± 75.41 min in subjects who received only phenytoin and 118.03 ± 66.82 min in subjects who received only levetiracetam (P = 0.428). Sedation time was significantly more when diazepam was given. It was 232.50 ± 153.03 min in the levetiracetam + diazepam (n = 12) group vs 118.03 ± 66.82 in the only levetiracetam group (n = 38) (P = 0.002) and 226.67 ± 115.14 min in the phenytoin + diazepam group (n = 18) vs 151.87 ± 75.41 in the only phenytoin group (n = 32) (P = 0.03).

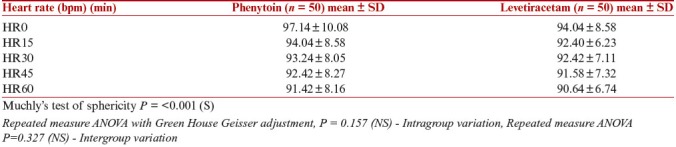

Among the clinical characteristics, Muchly’s test of sphericity for HR was significant (P < 0.05) i.e. there was no uniform pattern of variation in heart rate. Hence, repeated measures analysis of variance was applied with the Green House Geisser adjustment. Intragroup variation in HR from the onset of drug administration to 60 min was not significantly different in phenytoin and levetiracetam group (P = 0.157). When the two groups were compared for variation in HR from 0 min to 60 min there was no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.327) by applying repeated measures analysis of variance. [Table 4].

Table 4.

Heart rate variation in phenytoin group and levetiracetam group

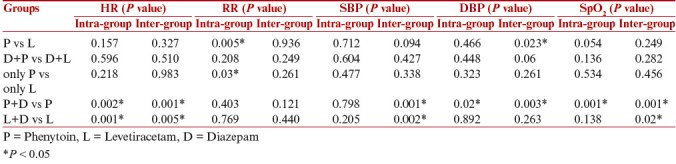

Intergroup comparison in diastolic BP revealed a lower diastolic BP in the phenytoin group as compared to levetiracetam group (P = 0.023). There was significant intragroup variation in RR in phenytoin and levetiracetam group (P = 0.005). Mean did not vary more than 2–3 breaths per min. It was clinically insignificant. All other parameters were comparable. Same parameters analyzed and compared between subjects who received only phenytoin and who received only levetiracetam revealed that there was significant intragroup variation within both the groups in respiratory rate (P = 0.03) but it was clinically insignificant. For rest of other parameters no significant intra or intergroup variation was observed (P > 0.05) [Table 5]. Among phenytoin + diazepam (n = 18) vs only phenytoin group (n = 32), there was significant intragroup variation (P < 0.05) in HR, DBP, SpO2, and intergroup variation in HR, SBP, DBP, and SpO2 (P < 0.05). When the parameters were analyzed and compared between subjects who received levetiracetam + diazepam (n = 12) and only levetiracetam (n = 38), there was significant intergroup variation in SBP and SpO2 (P < 0.05). All the variations were clinically insignificant [Table 5].

Table 5.

Comparison of cardiorespiratory parameters in various groups

Of the 47 patients followed up till 7 days in the levetiracetam group behavioral side effects in form of aggressive behavior or oppositional behavior were seen 6 patients (12.7%). Neuroimaging was carried out in 49 children in phenytoin group and 48 children in levetiracetam group. Neurocysticercosis was the commonest abnormality seen (52% in phenytoin group and 44% in levetiracetam group).

DISCUSSION

Overall efficacy was 96% in phenytoin group and 94% in levetiracetam group which was comparable.

Though there is no similar comparative study, several studies have reported the efficacy of levetiracetam. In a study, 4 patients with acute repetitive seizures and 2 with HIE responded to IV levetiracetam out of a total of 10 patients (60% efficacy).[5] In another study of 51 children, the efficacy of IV levetiracetam was 75% in terminating status epilepticus and 59% in patients with acute repetitive seizures.[6] Out of 32 patients, 47% patients with status epilepticus responded to IV levetiracetam.[7] In a retrospective study done in 10 Indian children aged 3 weeks to 19 years who received IV levetiracetam, 9 patients showed seizure cessation (90% efficacy).[8] Another study reported 89% as seizure free at 1 hr in response to IV levetiracetam.[9]

Among children who presented with seizures, long-term AEDs are required in those with two or more unprovoked generalized seizures or focal seizures.[2,3] Hence, intravenous loading of appropriate antiepileptic would help to achieve drug levels and prevent further seizures especially in the first 24 hrs. Phenytoin no longer remains the drug of choice for long-term therapy due to side effects such as gum hypertophy, hirsutism, and osteoporosis. Hence, increasing the need to give a loading dose of levetiracetam. If seizures do not recur patients are subsequently put on maintenance doses according to the type of seizure such as carbamazepine/valproate/levetiracetam in partial seizure and phenytoin/valproate/levetiracetam in second episode GTCS. This study reveals that efficacy of levetiracetam is comparable to phenytoin hence we can use a loading dose of levetiracetam wherever long-term antiepileptic therapy is planned with levetiracetam.

Intravenous diazepam is given when a patient presents seizures, as it takes less than 10 seconds to enter the brain and 8 minutes to reach peak brain concentration and effectively controls seizure activity. Since its distribution half-life is just 20.4 min, a long-acting antiepileptic is required to prevent the recurrence of seizures.[16] It is a common practice to give loading doses of phenytoin in all the patients after intravenous diazepam. Now levetiracetam can also be used in these situations whenever required. Because of short half-life of diazepam, our objective of comparing the efficacy of levetiracetam and phenytoin in controlling seizures for a 24-hr period was not affected.

About one-third of patients with status epilepticus may have persistent seizures refractory to first-line medications and required second line medications such as barbiturates, propofol or other agents. In developing countries where facilities for assisted ventilation are not readily available, use of non-sedating AEDs such as levetiracetam may be beneficial.[17]

In present study, age group was 3–12 years. Children of age less than 3 years were excluded from the study as metabolic abnormalities, malformation, and syndromes account for a major proportion of seizures occurring in this age group. In these children, seizures tend to recur despite anticonvulsant therapy until the underlying condition has been corrected. Children with clinical features suggestive of meningitis were also excluded for the similar reasons. Children with a history of acute head trauma were excluded from the study as most of them would require prompt neurosurgical intervention. The children in phenytoin and levetiracetam groups were comparable in terms of patient characteristics such as age and biochemical parameters. Thus we ensured inclusion of homogenous population.

In the present study, no effect was seen of the type of seizure over the administered drug. It was found equally effective in both GTCS and focal seizures as reported in earlier studies.[18,19]

In the levetiracetam group, all 50 (100%) children at 1 hr and 49 (98%) children at 24 hr achieved therapeutic levels. Therapeutic levels were taken as 6–45 mg/l in this study as per laboratory and kit specifications. Previous studies have revealed levels varying from 8–41 mcg/ml, 47–128 mcg/ml, 14–189 mcg/ml.[3,8,9] Thirty-eight (76%) patients were in the therapeutic range at 4 and 24 hrs in the phenytoin group. The drug levels did not correlate with the recurrence of seizure or efficacy of the antiepileptic as reported earlier.[20]

Children were sedated on IV infusion of both the drugs. Though statistically insignificant (P = 0.346) patients who received phenytoin had a higher sedation time than the levetiracetam group. If a child was not convulsing at presentation, we observed that time to regain consciousness was briefer in children who received levetiracetam only, rather than phenytoin only, though it was statistically insignificant (P = 0.428). No studies have reported sedation time of levetiracetam or compared it with phenytoin. The lesser sedative AED is likely to have a better outcome. Sedation time was significantly more when diazepam had to be administered [phenytoin + diazepam vs phenytoin groups (P = 0.03) and levetiracetam + diazepam and levetiracetam group (P = 0.002)].This was as expected due to the sedative effect of diazepam.

Secondary outcomes of the present study were the effect of treatment on the cardiorespiratory parameters such as BP, SpO2, HR, RR. Intergroup comparison in Diastolic BP revealed a lower Diastolic BP in the phenytoin group as compared to levetiracetam group (P = 0.023) as there are more chances of hypotension with phenytoin. There was significant intragroup variation in RR in phenytoin and levetiracetam group (P = 0.005). Mean did not vary more than 2–3 breaths per min. It was clinically insignificant.

Levetiracetam was found to have no significant side effects on cardiorespiratory parameters such as HR, RR, BP, SpO2 or ECG as reported in previous studies.[10,11,22] We administered levetiracetam in a dose of 30 mg/kg as a loading dose. Other studies have used doses varying from 20–150 mg/kg with no significant cardiorespiratory side effects.

Neurocysticercosis was seen in the majority of patients in both the groups as in 52% in phenytoin group and 44% in levetiracetam group responsible for both partial and generalized seizures. High prevalence of neurocysticercosis as a cause of partial epilepsy is well documented in earlier studies.[23]

In this study, intravenous levetiracetam was comparable to intravenous phenytoin in terms of seizure control. Time to sedation was shorter with levetiracetam than with phenytoin. With the proven safety and efficacy of IV levetiracetam in this study, it can be used for acute seizures when long-term therapy is indicated. Its role in status epilepticus after benzodiazepines or after loading of phenytoin needs to be evaluated further.

What is already known?

Phenytoin is efficacious in control of acute seizures in children. Levetiracetam is being increasingly used in both children and adults with no significant acute and long-term side effects. Levetiracetam is safe and efficacious in status epilepticus and acute seizures in children as reported in retrospective studies and case reports.

What does this study adds?

The efficacy of levetiracetam is comparable to that of phenytoin in acute childhood seizures. IV levetiracetam has lesser cardiorespiratory side effects than IV Phenytoin. A loading dose of 30 mg/kg of levetiracetam achieved therapeutic levels in most patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hauser, Allen W. The prevalence and incidence of convulsive disorders in children. Epilepsia. 1994;35:S1–S6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb05932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajyadhyaksha S, Kalra V, Potharaju NR, Singhi P, Shah KN, Yardi N, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of childhood epilepsy. Expert Committee on Pediatric Epilepsy, Indian Academy of Pediatrics. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:681–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheless JW, Clarke DF, Arzimanoglou A, Carpenter D. Treatment of pediatric epilepsy: European expert opinion. Epileptic Disord. 2007;9:353–412. doi: 10.1684/epd.2007.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abend NS, Monk HM, Licht DJ, Dlugos DJ. Intravenous levetiracetam in critically ill children with status epilepticus or acute repetitive seizures. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:505–10. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181a0e1cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McTague A, Kneen R, Kumar R, Spinty S, Appleton R. Intravenous levetiracetam in acute repetitive seizures and status epilepticus in children. Experience in a children’s hospital. Seizure. 2012;21:529–34. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirmani BF, Crisp ED, Kayani S, Rajab H. Role of intravenous levetiracetam in acute seizure management of children. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41:37–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiter PD, Huff AD, Knupp KG, Valuck R. Intravenous levetiracetam in the management of acute seizures in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2010;43:117–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goraya JS, Khurana DS, Valencia I, Melvin JJ, Cruz M, Legido A, et al. Intravenous levetiracetam in children with epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;38:177–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng YT, Hastriter EV, Cardenas JF, Khoury EM, Chapman KE. Intravenous levetiracetam in children with seizures: a prospective safety study. J Child Neurol. 2010;25:551–5. doi: 10.1177/0883073809348795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheless JW, Clarke D, Hovinga CA, Ellis M, Durmeier M, McGregor A, et al. Rapid infusion of a loading dose of intravenous levetiracetam with minimal dilution: a safety study. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:946–51. doi: 10.1177/0883073808331351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sasidaran K, Singhi S, Singhi P. Management of acute seizure and status epilepticus in pediatric emergency. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:510–7. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raj D, Gulati S, Lodha R. Status epilepticus. Indian J Pediatr. 2011;78:219–26. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0291-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, Alldredge B, Bleck TP, Glauser T, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17:3–23. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9695-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capovilla G, Beccaria F, Beghi E, Minicucci F, Sartori S, Vecchi M. Treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in childhood: Recommendations of the Italian League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl 7):23–34. doi: 10.1111/epi.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glauser T, Ben‐Menachem E, Bourgeois B, Cnaan A, Guerreiro C, Kalviainen R, et al. Updated ILAE evidence review of antiepileptic drug efficacy and effectiveness as initial monotherapy for epileptic seizures and syndromes. Epilepsia. 2013;54:551–63. doi: 10.1111/epi.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicol CF, Tutton JC, Smith BH. Parenteral diazepam in status epilepticus. Neurology. 1969;19:332–43. doi: 10.1212/wnl.19.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilad R, Izkovitz N, Dabby R, Rapoport A, Sadeh M, Weller B, et al. Treatment of status epilepticus and acute repetitive seizure with IV valproic acid versus phenytoin. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118:296–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berkovic SF, Knowlton RC, Leroy RF, Schiemann J, Falter U. Placebo-controlled study of levetiracetam in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Neurology. 2007;69:1751–60. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000268699.34614.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yılmaz U, Yılmaz TS, Dizdarer G, Akıncı G, Güzel O, Tekgül H. Efficacy and tolerability of the first antiepileptic drug in children with newly diagnosed idiopathic epilepsy. Seizure. 2014;23:252–9. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikati MA. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. In: Kleigman RM, Berhman RE, St. Geme III JW, Stanton BF, Schor NF, editors. Seizures in childhood. 19th ed. New Delhi: Saunders; 2011. pp. 2025–33. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arzimanoglou A, Guerrini R, Aicardi J. In: Aicardi's Epilepsy in Children. 3rd ed. Arzimanoglou A, Guerrini R, Aicardi J, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 363–86. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinstock A, Ruiz M, Gerard D, Toublanc N, Stockis A, Farooq O, et al. Prospective open-label, single-arm, multicenter, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic studies of intravenous levetiracetam in children with epilepsy. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:1423–9. doi: 10.1177/0883073813480241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggarwal A, Aneja S, Taluja V, Kumar R, Bhardwaj K. Etiology of partial epilepsy. Indian Pediatr. 1998;35:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]