Abstract

Human tail might be the most interesting cutaneous sign of neural tube defects. From little cutaneous appendixes to 20-cm-long taillike lesions were reported in the literature. They may occur connected to an underlying pathology such as lipoma or teratoma, but most of the time, they conceal an underlying spinal dysraphism. Many classifications about human tails have been suggested in history, but the main approach to these lesions is, independent of the classification, always the same: investigating the possible spinal dysraphism with concomitant pathologies and planning the treatment on the patient basis.

KEYWORDS: Human tail, lipomyelomeningocele, spina bifida, tethered cord

INTRODUCTION

Human tail is probably the most remarkable cutaneous sign of an underlying spinal dysraphism. These skinfolds are mostly seen in the lumbosacral area, and there are many theories and classifications about their embryological background.[1] Although accompanying abdominal and cardiac anomalies can be seen, the nature of the spinal dysraphism, which is almost always underlying, and the associated clinical picture interest neurosurgeons.

CASE REPORT

A 6-month-old baby boy was delivered vaginally by a 16-year-old nulliparous mother, who had not received prenatal care. The patient was admitted with a soft, skin-covered 4 × 4 × 5 cm mass with fluctuation on the lumbosacral area and a 15-cm-long tail extending from this mass [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Soft, skin-covered 4 × 4 × 5 cm mass with fluctuation on the right paramedian lumbosacral area, and a 15-cm-long skin appendix extending from this mass

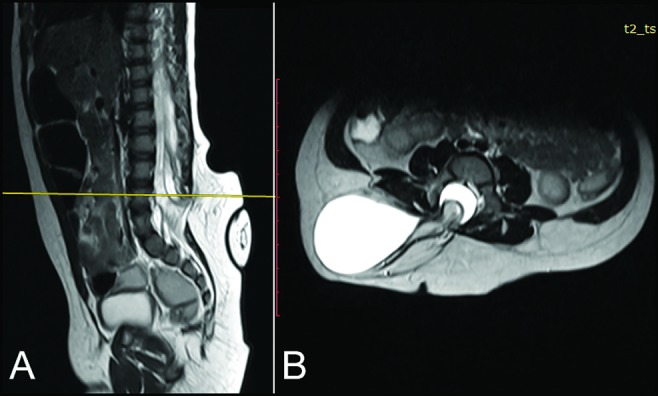

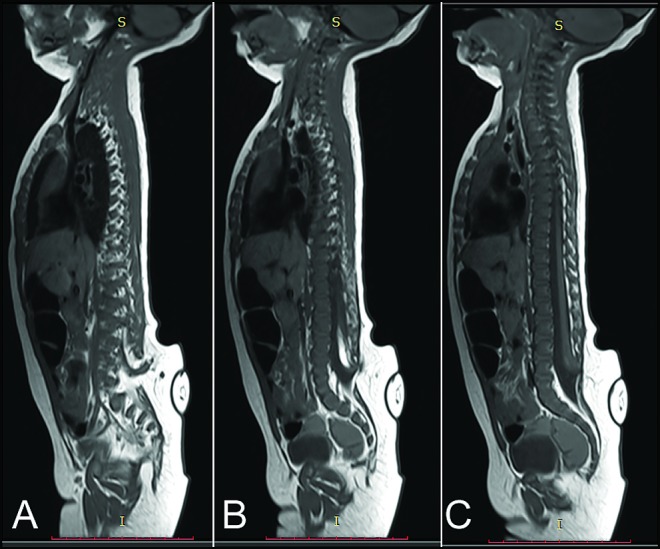

Neurological examination revealed no evident deficit. A decreased movement was observed in the distal right lower extremity. Patient’s cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was normal. Spinal MRI revealed 11-mm posterior fusion defects on L4, L5, and S1 levels and a 50 × 31 × 38 mm myelomeningocele sac that was extending rightward from the defect [Figure 2]. In T1 sequence, it was revealed that the lipomatous tissue was elongating through the spinal canal on L4 level. The spinal cord was ending on the L4 level and a thick, fatty filum terminale was seen on sacral levels [Figure 3]. Lipomyelomeningocele excision and tethered cord release operation were planned for the patient.

Figure 2.

Posterior fusion defects on L4, L5, and S1 levels and a 50 × 31 × 38 mm myelomeningocele sac, extending rightward from the defect: (A) Sagittal plane and (B) axial plan on level of L4 vertebrae

Figure 3.

(A and B) In T1 sequence, lipoma elongating through the spinal canal on L4 level. (C) Thick-fatty filum terminale on caudal part of the fusion defect

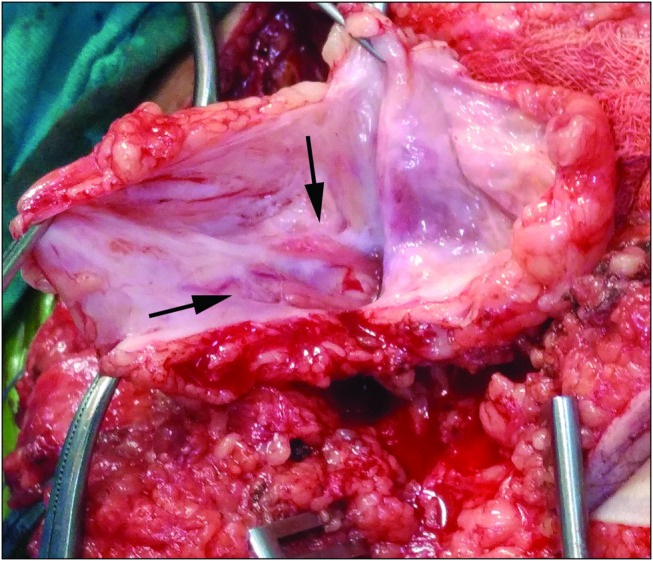

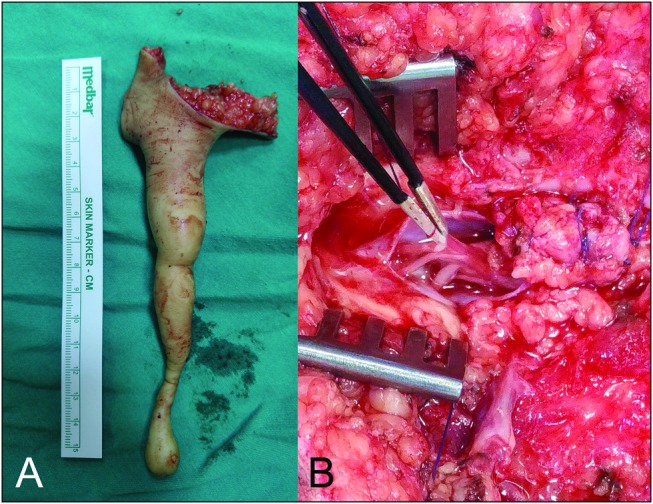

The patient was operated with neuro-monitorization. A curvilinear incision suited to mass’ position, which comprised both sides of the tail’s base, was performed. On L2 level, solid dura mater was reached and the layers through the defected zone were dissected. At the unification zone of the sac and the posterior defect, lipomatous and neural tissues extending from the tail were observed. Dura mater was incised caudally and the sac was opened. Nerve roots were observed on the interior wall of the sac [Figure 4]. Under the guidance of neuro-monitorization, the sac wall, lipomatous tissue and tail were excised [Figure 5A]. The incision was advanced caudally and sacral levels were explored. Fatty filum terminale was seen and excised [Figure 5B].

Figure 4.

Nerve roots on the interior wall of the sac

Figure 5.

(A) Excised tail. (B) Fatty filum

Pathological evaluation revealed only cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues, and no neural tissue was reported. No chromosomal or single-gene mutation was detected in the patient’s genetic evaluation.

Additional informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for this article.

DISCUSSION

Human tail is a general term for taillike skinfold lesions that occur usually on the lumbosacral and coccygeal levels. Because of concomitance with spinal dysraphism, when encountered with such a lesion, a possible underlying spina bifida occult must always be considered.

At the fourth week of the embryological life, sclerotomes are developed from somites, which begin to enfold the neural tube. In the fourth through sixth weeks, during the formation of vertebrae, the embryo has a tail that was formed by the 10–12 caudal vertebrae. At the end of the sixth week, vertebrae become the main support of the embryo on the axial plan. After this week, aforementioned caudal–coccygeal vertebrae start to dissolve by the phagocytes. At the end of the eighth week, except a few proximal caudal vertebrae, they all vanish. Remaining proximal vertebrae of the caudal level regress, and after birth, they fuse and form the coccyx. If this fusion was to be interrupted, the resulting deficit reveals as the “human tail” formation. This was the main theory to explain the pathophysiology since the 1900s.[1] In 1989, Gaskill and Marlin[2] suggested that these lesions may develop from the neuroectoderm, and they may be formed by the dermal sinus tracts, which extend out of the skin, as an alternative theory. Studies on “dermal sinuses” and “limited dorsal myeloschisis” by Pang et al. in 2013 also supported this theory.[3] This theory is also consistent with high rates of spinal dysraphism (50%) and tethered cord (81%) concomitance.[1,3] Considering the number and variety of accompanying anomalies (lipomyelomeningocele, myelocele, tethered cord, lipoma, anal atresia, horseshoe kidney, congenital heart disease, teratoma), it is suggested that there might be multiple pathologies causing this formation.[4,5] In cases accompanying both lipomyelomeningocele and tethered cord, such as the presented case, there are both primary and secondary neurulation defects. Both stages may be responsible for the formation of the tail.

The first classification on human tails was made by Bartel in 1884.[6] Bartel classified these appendixes into four categories according to the shape and the containment of an osseous tissue. In 1984, Dao and Netsky sorted human tails into two categories as true tails and pseudotails according to their embryological origins.[7] According to this classification, true tails are formed by embryological remnants and include muscle, adipose, and connective tissue but no vertebrae in their structure. Pseudotails are lesions that have an underlying pathology such as lipoma or teratoma.[8] Even though these classifications have embryological value, they are not very significant in clinical perspective. In 1998, Lu et al.[8] suggested different criteria for true tail–pseudotail classification. He referred coccygeal and gluteal benign lesions as true tails, and he suggested that basic excision was sufficient for its treatment. He described pseudotails as taillike lesions, accompanied by spinal dysraphism, and he explained that these taillike lesions have ectodermal origins caused by the concomitant spinal dysraphism.[8] This clinically helpful classification is used today, and the main approach toward human tail cases is to search for an accompanying spina bifida or other anomalies, analyze them, and decide the best way of treatment after these examinations. In 2016, a new classification that divided human tails into five groups—soft tissue caudal appendages, bony caudal appendages, bony caudal prominence, true tails, and other caudal appendages—was suggested.[9] Still, all of these classifications have more value for embryology than for clinical practice.

Radiological evaluation is indispensable in human tail cases. These lesions frequently contain spinal pathologies and, independently of all classifications studied, our target is to define these pathologies and to treat them one by one. We should perform MRI studies and focus on whether there is neural tissue stretching to the appendix. T1-weighted sequence is important in detecting lipomas. Potential tethered cord and accompanying spina bifida occult should always be kept in mind.[1]

CONCLUSION

Human tail cases should be examined both clinically and radiologically with great caution. There are many classifications on the basis of embryology and etiology; however, independent of these classifications, treatment should be planned specifically for the patient and the lesion. Neurosurgically, our aim was to determine concomitant pathologies with accuracy, to repair defects, and to maintain close follow-ups for these pediatric patients regarding development.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tubbs RS, Malefant J, Loukas M, Jerry Oakes W, Oskouian RJ, Fries FN. Enigmatic human tails: A review of their history, embryology, classification, and clinical manifestations. Clin Anat. 2016;29:430–8. doi: 10.1002/ca.22712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaskill SJ, Marlin AE. Neuroectodermal appendages: The human tail explained. Pediatric Neurosci. 1989;15:95–9. doi: 10.1159/000120450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pang D, Zovickian J, Wong ST, Hou YJ, Moes GS. Limited dorsal myeloschisis: A not-so-rare form of primary neurulation defect. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:1459–84. doi: 10.1007/s00381-013-2189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park SH, Huh JS, Cho KH, Shin YS, Kim SH, Ahn YH, et al. Teratoma in human tail lipoma. Pediatric Neurosurg. 2005;41:158–61. doi: 10.1159/000085876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donovan DJ, Pedersen RC. Human tail with noncontiguous intraspinal lipoma and spinal cord tethering: Case report and embryologic discussion. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2005;41:35–40. doi: 10.1159/000084863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartel S. Die geschwaanzten Menschen. Arch Anthropol Brnschwg. 1884;15:45–132. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dao AH, Netsky MG. Human tails and pseudotails. Hum Path. 1984;15:449–53. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu FL, Wang PJ, Teng RJ, Yau KI. The human tail. Pediatr Neurol. 1998;19:230–3. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(98)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkinson CC, Boylan AJ. Proposed caudal appendage classification system; spinal cord tethering associated with sacrococcygeal eversion. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017;33:69–89. doi: 10.1007/s00381-016-3208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]