Abstract

Down syndrome (DS), resulting from trisomy 21, is a common cause of mental retardation. Around 20,000 babies with DS are born every year in India. There is an increased risk of cerebral infarction in children with DS, the common causes being thromboembolism secondary to atrioventricular canal defects, right-to-left shunting, myocardial dysmotility, or cardiac valvular abnormalities. Stroke due to other causes can also occur in patients with DS, and one of these is moyamoya disease. This can be diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging and/or angiography in these patients. Here we report four cases of moyamoya disease in young patients with DS aged 2–3½ years, of a total of 500 cases with DS registered in the Genetic Clinic.

KEYWORDS: Aneuploidy, chromosomal disorder, hemiparesis, MRA, stroke

INTRODUCTION

Down syndrome (DS) is the most frequently occurring chromosomal abnormality leading to mental retardation in males and females. Few cases of DS with coexisting moyamoya disease (MMD) have been reported. MMD is a nonatherosclerotic condition characterized by progressive stenosis of terminal internal carotid artery (ICA) and proximal part of anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and middle cerebral artery (MCA). It is a rare cause of stroke in young age. The term “moyamoya disease” is used when there is bilateral ICA stenosis with associated collaterals, with no other related disease. The clinical features depend on the age of presentation: ischemic symptoms are more common in the young while the risk of hemorrhage increases with age. Children with MMD can present with clinical features ranging from transient ischemic attack to permanent neurological deficits, including sensory and motor deficits, headache, seizures, and involuntary movements. The diagnosis requires a high index of clinical suspicion and confirmation by cerebral angiography and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).[1,2,3,4] Etiopathogenesis of MMD in DS is sparse. We report four cases of DS admitted with stroke and diagnosed to have MMD.

CASE REPORTS

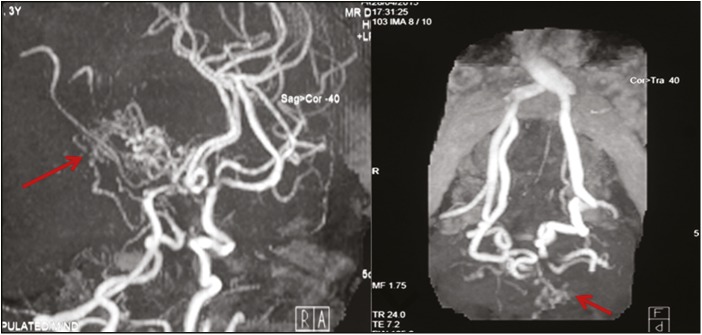

Of more than 500 patients of DS registered in the Genetic Clinic of the institute, median maternal age at conception in DS pregnancies was 28 years (range 18–42 years). We observed cardiac defects in more than 30% of the cases and MMD in four (~0.8%) of the cases of DS. The work-up and management of these four patients are described in Table 1. The MRA findings of Case 1 are shown in Figure 1.

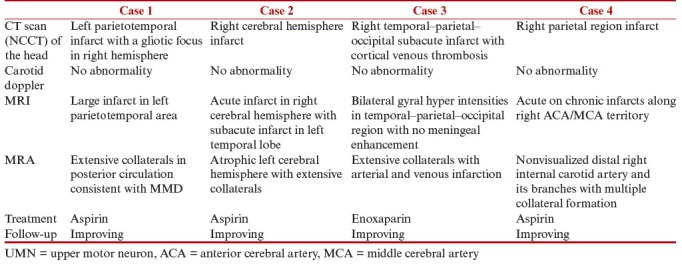

Table 1.

Clinical details, work-up, and management in the cases of DS with MMD

Figure 1.

MRA: abnormal tortuous collateral vessels from lenticulostriate and thalamoperforating group forming profuse network and giving characteristic “puff of smoke” appearance (arrows) with narrowing of terminal part of ICA and middle carotid artery bilaterally

Case 1

A 3-year-old boy, follow-up case of DS with history of transient ischemic attack 8 months back, presented with acute onset right hemiparesis with facial weakness. Examination revealed pallor with weakness, upper motor neuron (UMN) facial palsy, and UMN signs of right side. Possibility of acute ischemic stroke involving left MCA territory was kept. Noncontrast computed tomography (NCCT) of the head was suggestive of infarct in left parietotemporal area with a gliotic focus in the right hemisphere, possibly an old infarct. The child was started on aspirin, and neuroprotective strategy was ensured. For doubtful history of seizures, the child was started on phenytoin maintenance at 5 mg/kg/day. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was also suggestive of large infarct in left parietotemporal area, and MRA showed extensive collaterals in posterior circulation consistent with MMD [Figure 1]. Neurosurgery consultation was taken and conservative management was advised. The child was discharged on aspirin, and on short follow-up, the right hemiparesis was on improving trend with the child being hemodynamically stable.

Case 2

A 2-year-old boy presented with sudden onset left-sided hemiparesis and facial weakness since 18 days. The weakness was maximum at onset and started improving since day 2 of illness. On examination, the child had dysmorphism in the form of mongoloid slant, depressed nasal bridge, sandal gap suggestive of DS (confirmed by karyotyping), pallor, signs of rickets along with weakness, UMN facial palsy, and UMN signs of left side. Possibility of acute ischemic stroke involving right MCA territory was kept, and MRI and MRA of the brain were performed, which identified acute infarct in right cerebral hemisphere with subacute infarct in left temporal lobe and atrophic left cerebral hemisphere, suggestive of MMD. The child was started on aspirin, neuroprotective strategy along with seizure control. Oral aspirin was started and the child was discharged. At 6-month follow-up, right hemiparesis was on improving trend and the child was hemodynamically stable.

Case 3

A 3½-year-old boy was a follow-up case of DS with previous history of left-sided hemiparesis 3 months earlier, which was on improving trend. He presented again with sudden onset altered sensorium with right-sided hemiparesis. Because of low Glasgow Coma Scale score, the child remained intubated, subsequently found to have raised intracranial pressure, which was managed conservatively and became passive in next 36 h. At day 6 of hospital stay, sensorium of the child improved and was extubated. CT scan of the head showed bilateral gyral hyperintensities in temporal–parietal–occipital region with no meningeal enhancement, possibly subacute infarct with cortical venous thrombosis. Encephalopathy and right hemiparesis were attributed to cortical venous thrombosis and multiple cortical infarcts. During hospital stay, encephalopathy and right hemiparesis of the child improved. MRI, MRA, and magnetic resonance venography (MRV) of the brain revealed MMD with arterial and venous infarction and the child was started on enoxaparin and subsequently overlapped with warfarin. At discharge, the child was able to sit with support and hold neck, was able to feed (tube feeds), had power of 3/5 in all limbs, and was put on regular physiotherapy.

Case 4

A 7-year-old boy with DS, case of seizure disorder, presented with inability to move left upper and lower limbs for 3 days with urinary incontinence. There was no history of trauma, recent vaccination, or vomiting. He was on phenytoin 7 mg/kg/day with last seizures 18 months back. Clinical examination revealed DS facies, rudimentary preaxial polydactyly in left hand, clinodactyly with weakness on left side, and absent left radial pulse. Deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated. Result of fundus examination was normal. CT scan showed hypodense area in right parietal region suggestive of infarct. MRI showed nonvisualized distal right ICA and its branches with multiple collateral formation. There were acute or chronic infarcts along right ACA/MCA territory. The MRI features were consistent with MMD. On follow-up at 4.5 years after the episode, he was able to walk without support but still had mild weakness of limbs on the left side. There were no visual or hearing problems.

DISCUSSION

Cerebrovascular accidents are rare in children.[5] Thrombotic disorder, cardiac disorder, or infections are some common causes of stroke in young age. Cerebral infarction has been seen in children with DS due to underlying atrioventricular canal defects, myocardial dysmotility, right-to-left shunts, or cardiac valvular abnormalities in these patients. MMD is a rare cause of stroke in children with DS. The term “moyamoya” is a Japanese term that means “something hazy like a puff of cigarette smoke.” Pearson et al.[6] analyzed 37 cases of children with DS and found abnormalities suggestive of moyamoya syndrome in 7 patients. MMD occurs in DS three times more commonly than in the general population. The association between the two was described first in 1977. In a series of seven cases],[ the mean age of presentation was found to be 7 years.[7] However, in our study, the youngest DS child with MMD was only 2 years old.

The abnormalities seen in the circle of Willis are much more frequent in patients with DS as compared to cases with isolated congenital heart disease.[6] Several hypotheses have been proposed regarding the mechanism of DS-associated MMD. Cases with DS are predisposed to vascular disease and show retinal vessel abnormalities, abnormal capillary morphology of the nail beds, primary intimal fibroplasias, congenital heart disease, and high pulmonary vascular resistance.[8,9,10,11] Vascular dysplasia seen in DS may be responsible for the pathogenesis of MMD. Chromosome 21 encodes for certain proteins such as superoxide dismutase I, α-chains of collagen type VI, interferon-γ receptor, and cystathionine β-synthase. These proteins are associated with increased risk for vascular diseases in DS.[11] The role of autoimmunity is also proposed in the pathogenesis of MMD, in view of the fact that there is increase in autoimmune disorders such as autoimmune thyroid disease in DS.[12] MMD has also been found to be associated with antiphospholipid antibodies, predisposing these patients to arterial thrombosis.[13]

Children with MMD commonly present with hemiplegia. Transient or recurrent weakness and chorea are also seen.[14] In our case series also, the most common presentation was with hemiparesis, and one child had history of seizures. There was no predilection for involvement of left or right side of the body. Three criteria are required for the diagnosis of MMD: (a) stenosis of distal intracranial segment of ICA and proximal ACA and MCA, (b) abnormal vascular network near the stenosis, arising from thalamoperforate and lenticulostriate arteries, and (c) exclusion of other associated factors such as trauma, meningitis, sickle cell disease, tumor, or radiation therapy.[15,16] Management of these cases is still controversial with different opinions. Some authors recommend only medical treatment with aspirin, whereas some favor surgical treatment. The use of long-term anticoagulants for MMD is not recommended due to risk of hemorrhages in these patients. Surgical methods to revascularize areas of cerebral ischemia have been attempted; however, results are not very satisfactory.[17] These are encephaloarteriosynangiosis, encephalomyosynangiosis, superficial temporal artery to MCA anastomosis, and omental transplantation.[17] A recent report has suggested pial synangiosis to be a good modality of therapy in the patients with DS.[18]

Increased risk of MMD has also been seen in microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism, neurofibromatosis, and lysinuric protein intolerance. These may be having a common pathophysiology, and there are also genetic loci mutations that would, in addition, indicate higher susceptibility for MMD.[19,20,21] In a 2-year-old girl presenting with early onset of moyamoya syndrome with underlying DS, the genetic variant RNF213 p.R4810K was identified.[21]

CONCLUSION

The knowledge regarding the association of MMD in a patient with DS with stroke is important so as to reach a correct diagnosis and establish an appropriate management plan. The reason of this association is still not clear. The evaluation must include an MRA. Further advanced imaging, autoimmune work-up, or epigenetic studies are needed to find out underlying basis for increased incidence of MMD in trisomy 21 cases.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fukushima Y, Kondo Y, Kuroki Y, Miyake S, Iwamoto H, Sekido K, et al. Are Down syndrome patients predisposed to Moyamoya disease? Eur J Pediatr. 1986;144:516–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00441756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon N, Isler W. Childhood moyamoya disease. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1989;31:103–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1989.tb08418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorrotxategi P, Reguilón MJ, Gaztañaga R, Hernández Abenza J, Albisu Y. [Moya-moya disease in a child with multiple malformations] Rev Neurol. 1995;23:403–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jovanović Z. [Risk factors for stroke in young people] Srp Arh Celok Lek. 1996;124:232–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoenberg BS, Mellinger JF, Schoenberg DG. Cerebrovascular disease in infants and children: a study of incidence, clinical features, and survival. Neurology. 1978;28:763–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.8.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearson E, Lenn NJ, Cail WS. Moyamoya and other causes of stroke in patients with Down syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 1985;1:174–9. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(85)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer SC, Robertson RL, Dooling EC, Scott RM. Moyamoya and Down syndrome. Clinical and radiological features. Stroke. 1996;27:2131–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.11.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soto-Ares G, Hamon-Kerautret M, Leclerc X, Vallée L, Pruvo JP. [Moyamoya associated with Down syndrome] J Radiol. 1996;77:441–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagasaka T, Shiozawa Z, Kobayashi M, Shindo K, Tsunoda S, Amino A. Autopsy findings in Down’s syndrome with cerebrovascular disorder. Clin Neuropathol. 1996;15:145–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda K, Takahashi S, Higano S, Kurihara N, Haginoya K, Shirane R, et al. Cortical laminar necrosis in a patient with Moyamoya disease associated with Down syndrome: MR imaging findings. Radiat Med. 1997;15:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai AI, Shaikh ZA, Cohen ME. Early-onset moyamoya syndrome in a patient with Down syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:696–9. doi: 10.1177/088307380001501012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leno C, Mateo I, Cid C, Berciano J, Sedano C. Autoimmunity in Down’s syndrome: another possible mechanism of Moyamoya disease. Stroke. 1998;29:868–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.4.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del-Rio Camacho G, Orozco AL, Pérez-Higueras A, Camino López M, Al-Assir I, Ruiz-Moreno M. Moyamoya disease and sagittal sinus thrombosis in a child with Down’s syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:125–8. doi: 10.1007/s002470000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takanashi J, Sugita K, Honda A, Niimi H. Moyamoya syndrome in a patient with Down syndrome presenting with chorea. Pediatr Neurol. 1993;9:396–8. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(93)90111-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olds MV, Griebel RW, Hoffman HJ, Craven M, Chuang S, Schutz H. The surgical treatment of childhood moyamoya disease. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:675–80. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.5.0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaggero R, Donati PT, Curia R, De Negri M. Occlusion of unilateral carotid artery in Down syndrome. Brain Dev. 1996;18:81–3. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(95)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsushima T, Inoue T, Suzuki SO, Fujii K, Fukui M, Hasuo K. Surgical treatment of moyamoya disease in pediatric patients—comparison between the results of indirect and direct revascularization procedures. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:401–5. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.See AP, Ropper AE, Underberg DL, Robertson RL, Scott RM, Smith ER. Down syndrome and moyamoya: clinical presentation and surgical management. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;16:58–63. doi: 10.3171/2014.12.PEDS14563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kainth DS, Chaudhry SA, Kainth HS, Suri FK, Qureshi AI. Prevalence and characteristics of concurrent Down syndrome in patients with moyamoya disease. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:210–5. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31827b9beb. discussion 215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghilain V, Wiame E, Fomekong E, Vincent MF, Dumitriu D, Nassogne MC. Unusual association between lysinuric protein intolerance and moyamoya vasculopathy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20:777–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chong PF, Ogata R, Kobayashi H, Koizumi A, Kira R. Early onset of moyamoya syndrome in a Down syndrome patient with the genetic variant RNF213 p.R4810k. Brain Dev. 2015;37:822–4. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]