Abstract

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by dermatologic manifestations and growth of multiple benign tumors often involving the brain, skin, kidneys, heart, lungs, and liver. It exhibits wide phenotypic variation, ranging from the most severe cases with intellectual disability and intractable epilepsy to the mildest, clinically silent forms of the disease. The incidence of TSC is reported to be 1/6000; however, this does not account for those with milder forms of the disease, of which forme fruste is the mildest. Forme fruste is a French term for a “crude or unfinished form.” In medicine, it refers to an atypical or attenuated manifestation of a clinical condition and implies an incomplete, partial, or an aborted disease state. Here, we describe a rare case of forme fruste TSC incidentally diagnosed in an otherwise healthy child, highlighting the implications of the diagnosis for treatment and screening in similarly affected pediatric patients.

KEYWORDS: Forme fruste, pediatric, tuberous sclerosis complex

INTRODUCTION

Forme fruste tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) was first described by Schuster in 1914 in patients with cutaneous angiofibromas without intellectual or developmental delay.[1] At present, little is known about forme fruste TSC, and most literature is based on adult patients. To the best of our knowledge, forme fruste TSC has not been described in a previously asymptomatic child. Early recognition and diagnosis of forme fruste TSC is critical for reducing the disease burden through screening and appropriate follow-up.

CASE HISTORY

A 9-year-old previously healthy girl presented to our clinic for evaluation of abnormal findings on the brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This was completed at an outside hospital for new-onset headaches with migrainous features. Birth history and family history were largely unknown as patient was adopted at 8 months of age. Of note, she met all her developmental milestones on time and was performing well in school without any learning problems.

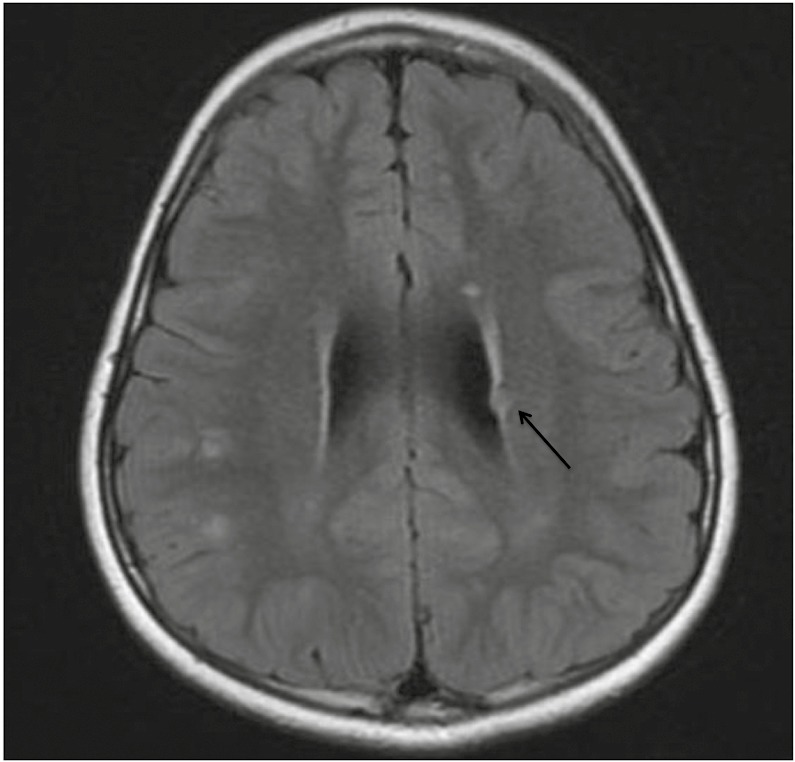

Interestingly, her MRI of the brain with contrast was reported as having subcortical lesions in the right perirolandic region and multiple focal white matter lesions at the gray–white junction in the frontal and parietal lobes in addition to subependymal nodules along the right and left ventricles, which were best identified on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging and were consistent with TSC [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Axial FLAIR MRI of the brain showing hyperintense lesions suggestive of cortical/subcortical tubers. A 6-mm subependymal nodule is seen in the left deep frontal white matter (black arrow).

The patient had no history of skin lesions, seizures, cardiac, pulmonary, or renal problems. A renal ultrasound performed in the past for an episode of urinary tract infection was unremarkable. She had no ophthalmological complaints, and had three normal-routine ophthalmological assessments in the past. On clinical examination, no dental pits or intraoral masses were identified. No cutaneous stigmata of TSC were seen, even on a Wood’s lamp inspection. Neurological examination, including a funduscopic examination, was unremarkable. On the basis of the MRI findings of subcortical tubers and subependymal nodules, she was diagnosed with TSC as per the Updated Diagnostic Criteria for Tuberous Sclerosis Complex, 2012.[2] However, given the fact that she had no other stigmata of TSC, we believe that her presentation is consistent with a forme fruste TSC. Nevertheless, genetic counseling and an annual TSC surveillance were recommended.

DISCUSSION

Early recognition and diagnosis of TSC is critical to improving the morbidity and mortality of the disease. This remains a challenge for patients with forme fruste who present with mild or absent subjective or external manifestations of the disease but are found to have stigmata of TSC on examination or investigations. So far, only two cases in the literature describe forme fruste TSC in children. The first describes a 7-year-old child of normal intelligence with intractable epilepsy since the newborn period who underwent single-photon emission computed tomography–guided surgery. Pathologic examination of the excised lesions was consistent with TSC and the child was diagnosed with forme fruste given the lack of intellectual disability or tubers elsewhere in the body.[3] The second describes a 16-year-old with cutaneous facial lesions thought to be acne vulgaris but ultimately found to be angiofibromas. Further workup revealed three subependymal nodules and bilateral renal angiomyolipomas. This patient was asymptomatic and without epilepsy or intellectual disability, similar to our patient.[4] More often, cases of forme fruste TSC are reported in literature when average intelligence parents of affected children are screened for hidden forms of the disease. Reported cases of forme fruste parents include two asymptomatic parents who each had a single subependymal nodule on CT scan, and a parent found to have multiple cutaneous stigmata of the disease, retinal hamartomas, and intracranial calcifications.[5,6,7]

Since their initial recognition, it has been discovered that formes frustes have a much milder phenotype on MRI compared to a “classical” appearance. As such, a “junction image” created by either morphometric MRI analysis or FLAIR sequences are strongly recommended to improve the rate of detection of small tubers in these patients.[8,9] Use of sensitive techniques to detect small or previously unrecognized tubers is especially important in those patients at risk of having affected children.

Understanding that manifestations of traditional TSC continue to evolve over a patient’s life, management in clinically silent patients includes annual TSC surveillance and neurological observation in younger patients as there is a risk of refractory epilepsy. Recommendations for TSC surveillance were recently updated by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference and can serve as a guide for screening patients with forme fruste.[10] It is also important that patients with forme fruste TSC receive genetic counseling before starting a family, as it follows an autosomal dominant pattern and the severity of disease in the child may be much greater than that of the parent, as evidenced by the cases discussed earlier. Although little is known about the prognosis of patients with forme fruste, review of cases in the literature leads us to believe a wide variety and severity of disease manifestations are possible; and, given the recent advances in the management of TSC, it is imperative to identify and regularly follow-up these patients to minimize the disease burden.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. David Walsh, Thomas Koch, and Ramin Eskandari, and acknowledge the support provided by the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Neurology at the Medical University of South Carolina to publish this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Curatolo P. Tuberous sclerosis complex: from basic science to clinical phenotypes. In: Curatolo P, Bax MCO, editors. Historical background. London: Mac Keith Press; 2003. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Northrup H, Krueger DA. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang JM, Son EI, Kim IM, Lee CY. Ictal SPECT-guided epilepsy surgery in a patient with forme fruste tuberous sclerosis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2004;36:490–2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lungu M, Ursoiu A. Bourneville tuberous sclerosis—difficulties of the diagnosis—a case report. Glob J Med Res (A) 2014;14:35–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altman NR, Purser RK, Post MJ. Tuberous sclerosis: characteristics at CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;167:527–32. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.2.3357966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards TA. A clinical and genetic study of tuberous sclerosis (master’s thesis) 1972:22–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheig RL, Bornstein P. Tuberous sclerosis in the adult. An unusual case without mental deficiency or epilepsy. Arch Intern Med. 1961;108:789–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1961.03620110129017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.House PM, Holst B, Lindenau M, Voges B, Kohl B, Martens T, et al. Morphometric MRI analysis enhances visualization of cortical tubers in tuberous sclerosis. Epilepsy Res. 2015;117:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takanashi J, Sugita K, Fujii K, Niimi H. MR evaluation of tuberous sclerosis: increased sensitivity with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and relation to severity of seizures and mental retardation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1923–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krueger DA, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: recommendations of the 2012 international tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:255–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]