Abstract

Introduction

Separation from a parent during childhood has been linked with heightened longer-term violence risk, but it remains unclear how this relationship varies by gender, separation subgroup, and age at separation. This phenomenon was investigated by examining a wide array of child–parent separation scenarios.

Methods

National cohort study including individuals born in Denmark, 1971–1997 (N=1,346,772). Child–parent separation status was ascertained each year from birth to 15th birthday, using residential addresses from the Danish register. Members were followed up from their 15th birthday until the date of first violent offense conviction, or December 31, 2012. Incidence rate ratios were estimated using survival analyses techniques. Analyses were conducted during 2016–2017.

Results

Separation from a parent during childhood was associated with elevated risk for subsequent violent offending versus those who lived continuously with both parents. These links were attenuated but persisted after adjustment for parental SES. Associations were stronger for paternal than for maternal separation at least up until mid-childhood and rose with the number of separations. Separation from a father for the first time at a younger age was associated with higher risks than if paternal separation first occurred at an older age, but there was little variation in risk associated with age at first maternal separation. Increasing risks were linked with rising age at first separation from both parents.

Conclusions

Violence prevention should include strategies to tackle a range of correlated familial adversities, with promoting a stable home environment being one salient aspect.

Introduction

Family structures in Western societies have changed markedly over recent decades, with fewer marriages, higher divorce rates, and more children being brought up in single, step, and cohabiting families.1, 2, 3 By the mid-1990s, it was estimated that more than a third of children in the U.S. had experienced at least one family structure change on reaching adolescence.4 A stable home environment has long been recognized as being conducive to healthy child development. Children exposed to parental separation have been reported to show poorer well-being and mental health during childhood and adulthood, compared with those with parents who never separated or divorced.5, 6, 7 Exposure to parental separation has also been linked with elevated risk for delinquency and violence,8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 but despite there being a notable body of research on this topic, large gaps in understanding remain. For example, limited and conflicting evidence exists regarding how associations vary by separation from mother only, father only, or from both parents,8, 15, 16 by offspring gender,9, 17, 18 and timing of child–parent separation,9, 15, 19 especially in relation to subsequent violent criminality risk. In addition, although a substantial minority of children experience multiple family structure changes,4 parental separation has commonly been investigated as a static exposure.8, 13, 14 Few studies have explored family structure dynamics and offspring’s later risk for antisocial behaviors, and those that have investigated these phenomena have usually been somewhat limited in their follow-up measurements (e.g., parental separation status measured at two timepoints only11, 12).

Using comprehensive and accurate national registration of residential address information for every Danish resident, and complete child–parent linkage and several other inter-register linkages, a large epidemiologic study investigating the associations between child–parent separation and violent criminality risk from the 15th birthday through to mid-adulthood is described. Variations in relationships are explored across an array of child–parent separation scenarios and trajectories from birth to age 15 years, and by gender of the parents and of the offspring, by age at first separation, and by number of separations experienced.

Methods

Study Population

The study cohort was delineated using data from the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS). Date and place of birth, gender, parental identities, and continuously updated information including residential addresses and vital status, have been recorded in the CRS since 1968 for all Danish residents.20 Using the unique personal identification number assigned to every resident, accurate linkage across all national registers is possible. The cohort consisted of all individuals born in Denmark during 1971–1997 who were residing in the country on their 15th birthdays, with the identities of both parents known who were also Danish-born and were alive on cohort members’ 15th birthdays. Individuals who experienced parental death before their 15th birthday, and those whose mothers’ or fathers’ identifies were unknown, were excluded. Individuals who had missing information on child–parent separation status in any one year up to their 15th birthday (0.44% of the study population), and those who were separated from both parents at birth but were subsequently registered as living with at least one parent (1.0%), were also excluded. The final study cohort consisted of 1,346,772 people.

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency, and data access was agreed by the State Serum Institute and Statistics Denmark. Because this project was based exclusively on registry data, according to the Danish Act on Processing of Personal Data, Section 10, informed consent from cohort members was not required.

Measures

Residential addresses were used to determine whether cohort members were living with their parents. This information has been recorded in the CRS since 1971, and Danish residents are required by law to inform the authorities of any changes to their permanent address. Child–parent separation status was classified as: no separation (i.e., living with both parents); paternal separation (living with mother but not father); maternal separation (living with father but not mother); paternal and maternal separation (not living with either parent). This classification was made in relation to day of birth and each birthday from the individual’s first to 15th.

Information on convictions for the following violent crimes were extracted from the National Crime Register21: homicide, assault, robbery, aggravated burglary or arson, possessing a weapon in a public place, violent threats, extortion, human trafficking, abduction and kidnapping, rioting and other public order offenses, terrorism, and sexual offenses. The first violent offense conviction after cohort members’ 15th birthdays—the age when criminal responsibility commences in Denmark—was examined.

Parental SES was assessed in the year of cohort members’ 15th birthdays, comprising six measures: maternal and paternal income (quintiles); highest levels of maternal and paternal educational attainment (primary school, high school/vocational training, higher education); and maternal and paternal employment status (employed, unemployed, outside workforce for other reasons). This information was obtained from the Integrated Database for Labour Market Research.22

Statistical Analysis

Cohort members were followed up from their 15th birthdays until date of first conviction for a violent offense, death, emigration from Denmark, or December 31, 2012, whichever came first, for a total of 16.3 million person-years. Because cohort members were born between 1971 and 1997, their follow-up began on different dates and duration of follow-up also varied. The amount of person-time at risk that each cohort member could possibly contribute ranged from 1 day to a day short of 27 years. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for violent offending were estimated by log-linear Poisson regression, fitted using the SAS, version 9.4 GENMOD procedure, with the logarithms of person-years as offset variables. This is equivalent to the Cox proportional hazards model, assuming piecewise constant incidence rates.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Models were adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, interactions between these variables, and the six measures of parental SES. Age and calendar year were treated as time-dependent variable; gender and parental SES were time-fixed variables. Likelihood ratio–based 95% CIs were calculated for each IRR point estimate, and likelihood ratio interaction tests were used to assess effect modification by offspring gender. Cumulative incidence, which measures the risk (probability) to have committed a violent crime before the 40th birthday, was calculated using competing risk survival analysis, taking into account emigration or death.24 Analyses were conducted during 2016–2017.

Results

A total of 37,415 individuals (2.8% of the study cohort) were convicted of a first violent offense during the observation period, with 33,671 (90.0%) of offenders being male (Appendix Table 1, available online). Table 1 shows the IRRs for violent offending associated with child–parent separation status at birth and at 15th birthday, adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, and parental SES. More than 93% of the study population lived with both parents at time of birth, falling to 71% at age 15 years. Being separated from a parent at age 15 years was linked with a greater elevation in violent offending risk than that associated with separation at birth. Elevated risk linked with paternal separation at birth was higher than for maternal separation at this time, but there was little risk differential by paternal versus maternal separation at age 15 years. IRRs not adjusted for parental SES are presented in Appendix Table 2 (available online), with roughly a quarter to a half of elevated risks explained by parental SES. Cumulative incidence (absolute risk) is reported in Appendix Table 3 (available online), with the highest values being among cohort members who were separated from both parents at their 15th birthdays. Approximately one in four males and one in 19 females in this group will be convicted for committing a violent crime by age 40 years. Absolute risks were consistently higher for males than for females, although relative risks were greater for females (Table 1).

Table 1.

Incidence Rate Ratios (IRR) for Violent Criminality by Child–Parent Separation Status at Birth and at 15th Birthday

| Child-parent separation status | % | Number of cases of violent offending | Incidence rate (per 10,000 person-years) | Males and females, IRR (95% CI)a | Males, IRR (95% CI)b | Females, IRR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At birthc | ||||||

| Separated from father | 6.3 | 5,337 | 52.0 | 1.78 (1.73, 1.83) | 1.71 (1.65, 1.76) | 2.46 (2.27, 2.67) |

| Separated from mother | 0.17 | 102 | 26.1 | 1.36 (1.11, 1.64) | 1.30 (1.05, 1.59) | 2.07 (1.11, 3.48) |

| Separated from both parents | 0.21 | 42 | 7.17 | 0.49 (0.36, 0.66) | 0.52 (0.30, 0.70) | —e |

| Not separated from either parent | 93.4 | 31,934 | 21.1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| At 15th birthdayd | ||||||

| Separated from father | 22.9 | 13,367 | 39.5 | 2.03 (1.98, 2.08) | 1.95 (1.90, 2.00) | 2.97 (2.76, 3.19) |

| Separated from mother | 4.2 | 2,942 | 46.9 | 2.16 (2.07, 2.24) | 2.09 (2.00, 2.17) | 3.14 (2.74, 3.58) |

| Separated from both parents | 1.8 | 2,841 | 95.0 | 3.60 (3.45, 3.75) | 3.30 (3.15, 3.45) | 7.47 (6.68, 8.33) |

| Not separated from either parent | 71.1 | 18,265 | 15.3 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

Models adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, interactions between these variables, and parental SES.

Models adjusted for age, calendar year, their interactions, and parental SES.

For child–parent separation status at birth, test of gender differences in IRRs, χ2(3) = 68.43, p<0.001.

For child–parent separation status at 15th birthday, test of gender differences in IRRs, χ2(3) = 229.6, p<0.001.

IRR associated with paternal and maternal separation at birth not reported as it was based on fewer than 10 cases.

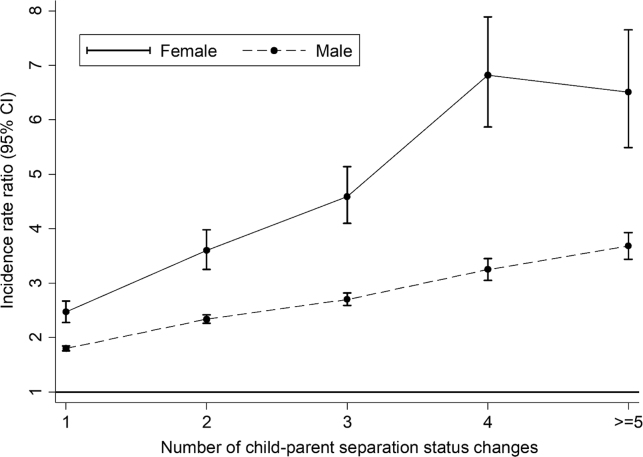

Between birth and the 15th birthday, child–parent separation status remained unchanged for 67.6% of cohort members. Another 21.1% experienced one separation status change; 6.3% and 3.1% had two and three changes, respectively, whereas 1.8% experienced four or more changes. Figure 1 shows gender-specific IRRs for violent offending by total number of separation status changes. Relative risks were consistently higher for females than for males (chi-square [5]=173.19, p<0.001). Compared with those with no changes in child–parent separation status through childhood, violent offending risks for males were elevated almost linearly with increasing number of changes, whereas relative risks rose more sharply for females.

Figure 1.

Gender-specific incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for violent criminality by the total number of child–parent separation status changes from birth through 15th birthday.a,b,c

aReference for IRR estimation: Persons with no child-parent separation status changes from birth through 15th birthday.

bModels adjusted for age, calendar year, their interactions, and parental SES.

cTest of gender differences in IRRs: χ2(5)=173.19, p<0.001.

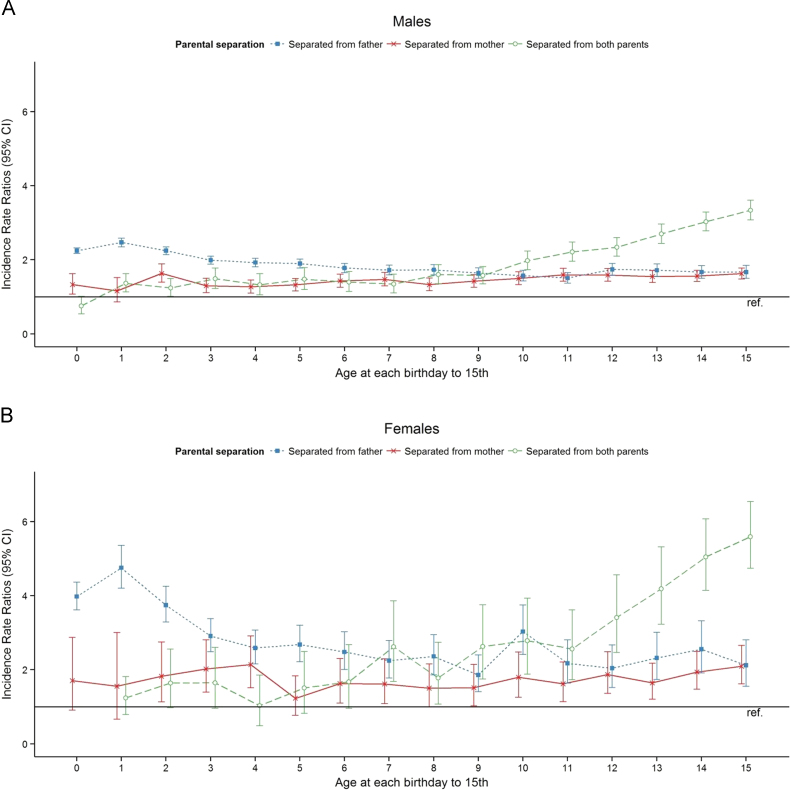

Figure 2 shows the gender-specific IRRs for violent offending by age at first child–parent separation and type of separation. For both genders, being separated from the father for the first time at a younger age was associated with higher risks than if paternal separation first occurred at an older age, but there was little variation in risk associated with age at first maternal separation. On the contrary, increasing risks were found with older age at first separation from both parents. For females, first separation from the father at any age was associated with greater elevation in risks than separation from the mother at the same age. The same was also found for males when separation first occurred before mid-childhood, but thereafter there were no observed differentials in relative risks associated with maternal versus paternal separation.

Figure 2.

Gender-specific incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for violent criminality by age at first child–parent separation and by specific type of separation.a,b,c

aFor each separation type, the reference group for IRR estimation was people who had not experienced that separation type at any time from birth to 15th birthday.

bFor females, IRR of violent offending associated with separation from both parents at birth was not reported as it was based on fewer than 10 cases.

cModels adjusted for age, calendar year, their interactions, and parental SES.

Each specific child–parent separation trajectory from birth to 15th birthday that affected >0.1% of the study population was investigated (Table 2). Because of the small number of female violence perpetrators in some trajectories, gender-specific analyses were not conducted. All separation trajectories were associated with elevated risks of violent offending versus those who continuously lived with both parents (i.e., N=separated from neither parent), except for those who were separated from both parents at birth and remained so through childhood (FM= separated from father and from mother). Elevated risk was observed even when the children ultimately lived with both parents again after a period of separation (trajectories ending with N). For those who lived with both parents at birth, subsequent paternal separation (N→F) was associated with higher violent criminality risk than maternal separation (N→M), and this was also observed for those who ultimately lived with both parents again (N→F→N versus N→M→N). In addition, risk was particularly raised for those who experienced the following separation trajectories:

-

•

N→F→FM→F, which signifies the trajectory of living with both parents at birth, followed by separation from the father, then additionally from the mother, and eventually reunited with the mother only, IRR=4.90, 95% CI=4.36, 5.49.

-

•

N→F→FM, which signifies the trajectory of living with both parents at birth, followed by separation from the father, then additionally from the mother, IRR=4.74, 95% CI=4.39, 5.10.

-

•

F→FM, which signifies the trajectory of being separated from the father at birth, then additionally from the mother, IRR=4.51, 95% CI=4.07, 4.99.

Table 2.

Incidence Rate Ratios (IRRs) for Later Violent Criminality in Relation to Specific Child–Parent Separation Trajectories From Birth to Age 15 Yearsa

| Separation trajectoriesa | Exposure prevalence (%) | Number of cases of violent offending | Incidence rate (per 10,000 person-years) | IRR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 65.4 | 15,119 | 13.8 | 1.00 (ref) |

| N→F | 16.3 | 7,702 | 32.1 | 1.99 (1.94, 2.05) |

| N→F→N | 2.46 | 1,204 | 32.0 | 2.03 (1.91, 2.15) |

| N→M | 2.16 | 1,094 | 31.5 | 1.79 (1.68, 1.90) |

| F | 2.01 | 1,643 | 53.3 | 2.69 (2.55, 2.83) |

| F→N | 1.92 | 901 | 24.8 | 1.79 (1.67, 1.91) |

| N→F→N→F | 1.65 | 1,161 | 47.2 | 2.56 (2.41, 2.72) |

| N→F→M | 1.12 | 806 | 56.1 | 2.80 (2.60, 3.00) |

| F→N→F | 0.91 | 740 | 52.0 | 2.77 (2.57, 2.98) |

| N→M→F | 0.55 | 277 | 36.4 | 2.18 (1.93, 2.45) |

| N→F→FM | 0.41 | 770 | 130 | 4.74 (4.39, 5.10) |

| N→FM | 0.40 | 432 | 60.9 | 3.15 (2.86, 3.47) |

| N→M→N | 0.33 | 124 | 23.0 | 1.53 (1.28, 1.82) |

| N→F→M→F | 0.29 | 233 | 65.7 | 3.44 (3.01, 3.91) |

| N→F→N→F→N | 0.28 | 233 | 55.3 | 2.92 (2.55, 3.31) |

| F→FM | 0.21 | 394 | 134 | 4.51 (4.07, 4.99) |

| FM | 0.21 | 42 | 7.17 | 0.68 (0.49, 0.91) |

| F→N→F→N | 0.21 | 175 | 50.5 | 2.94 (2.53, 3.41) |

| N→F→N→F→N→F | 0.17 | 165 | 63.4 | 3.03 (2.59, 3.52) |

| N→F→FM→F | 0.16 | 302 | 113 | 4.90 (4.36, 5.49) |

| N→FM→N | 0.15 | 140 | 46.8 | 2.93 (2.47, 3.45) |

| F→N→F→N→F | 0.14 | 159 | 71.0 | 3.45 (2.94, 4.02) |

| N→F→N→M | 0.14 | 136 | 64.7 | 3.17 (2.67, 3.74) |

| N→F→N→F→M | 0.12 | 138 | 86.3 | 3.64 (3.06, 4.29) |

| Other | 2.33 | 3,325 | 92.3 | 4.22 (4.06, 4.40) |

N=Not separated from either parent (i.e., living with both parents); F=separated from father; M=separated from mother; FM=separated from both parents.

Models adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, interactions between these variables, and parental SES.

Children grouped under one of these three trajectories all had one experience in common: They were all separated from their father initially and then subsequently from their mother at some time during their childhood.

Discussion

In this study of more than 1.3 million people, family structure instability was found to be associated with elevated risk for subsequent violent criminal offending versus those who lived continuously with both parents throughout their upbringing. These links were attenuated but persisted after adjustment for parental SES. Although absolute risks were higher for males than for females, relative risks were greater for females. Relative risks were also greater for paternal versus maternal separation at least up until mid-childhood and rose with the number of separation status changes. Elevated risks were found for all separation scenarios investigated, except for when the child was separated from both parents at birth and remained separated through childhood. Separation from a father for the first time at a younger age was associated with higher risks than if paternal separation first occurred at an older age, but there was little variation in risk associated with age at first maternal separation. On the contrary, increasing risks were linked with older age at first separation from both parents.

Although associations between child–parent separation and interpersonal violence risk have previously been reported,10, 11, 13, 14, 31, 32 the dynamic nature of separation status has largely been neglected. Complete and accurate national registration of residential information in Denmark provided a unique opportunity to investigate a wide array of child–parent separation trajectories. Examination of a national cohort also provided abundant statistical power to investigate associations by gender of both cohort members and their parents, and prospective collection of the registry data ensured that exposure and outcome were assessed independently and were therefore free from recall bias. Males are much more likely than females to perpetrate violent crimes,33 and studies on child–parent separation and violent criminality risk have therefore commonly examined males alone.11, 14, 31, 32 The small number of studies that have investigated gender-specific associations have reported contrasting evidence. For example, Fergusson et al.9, 10 found no significant gender interactions between exposure to single parenthood or parental separation during childhood and subsequent risk for delinquency or criminality. On the contrary, Fomby and Sennott34 and Ilomaki and colleagues18 reported that links between family structure instability and adolescent delinquency were stronger for females than for males. There have also been conflicting reports regarding strengths of association according to maternal versus paternal separation8, 15, 16 and by timing of separation.9, 15, 19 Utilizing national registry data in the absence of attrition and exposure and outcome ascertainment bias has produced robust evidence for the risk patterns examined. In addition, the particularly large risk elevations observed among individuals who were separated initially from their father only and subsequently from both parents concur with previously reported findings on self-harm risk,6 suggesting that those who experience these specific child–parent separation trajectories are particularly vulnerable to these two correlated adverse outcomes.35

Children who have experienced separation from a parent are likely to have been exposed to parental conflict—a reported risk factor for adolescent offending even in the absence of family change.36 Child–parent separation increases the likelihood of disrupted family routines, reduced parental monitoring, negative parenting behaviors, insecure child–parent attachment, and reduced economic resources, all of which have been linked with heightened risk for developing psychopathology and problematic or maladaptive behaviors during childhood.8, 37, 38, 39, 40 Those who have experienced multiple familial transitions are particularly disadvantaged,4, 17, 41 as each separation could involve stressful adjustment periods, having a cumulative impact on a child’s well-being.17 Cumulative family instability in early childhood has been linked with poorer subsequent social development and increased risk of externalizing behaviors.41 Changes in living arrangements, particularly for children separated from both parents, may also entail residential and school changes, leading to disrupted social and support networks.34 Frequent residential change, especially during adolescence, has been associated with elevated risk of violent offending subsequently, with these links also being stronger for females than for males.42

Causality cannot be assumed or inferred from any observational study including this one, however. Familial adversities are often interrelated, and multiple family transitions may not only represent broken parental relationships, but also a myriad of other household dysfunctionalities.43 For example, children from fragmented families are at increased risk of witnessing abuse or being abused,43 which strongly predicts later violence perpetration by these individuals themselves.18, 44, 45, 46 In addition, aggression and violence are known to run in families via putative genetic and environmental pathways.47 Parental antisocial traits could influence not only the quality of child–parental relationships but also the environment children are brought up in, and therefore their likelihood of subsequent delinquency.48, 49 Although increasing violent offending risk was observed with rising number of separation status changes, those who continued to live with their mother only (trajectory F) also showed elevated risk, which was higher than some trajectories linked with at least one status change. Therefore, familial difficulties associated with single parenthood, instability, and other household adversities correlated with child–parent separation, and selection mechanisms, are all likely to contribute to the findings reported here.

The only scenario where no elevated risk was observed was amongst those who never lived with a parent from birth through to their 15th birthday. In a previous registry study, this group also showed no increased risk for self-harm.6 It could be that children placed in the care of the Danish social services from birth have been particularly well looked after and are thereby shielded from familial discord and other familial environmental adversities through their childhood.

Limitations

This study’s most significant limitation was that parental violent offending could not be adjusted for.47 Criminal offending data were only available from 1981 onwards, so histories of parental offending are incomplete for many cohort members. Adjustment for childhood experiences of abuse was also not possible as these data are not routinely registered in Denmark. Because parental links are based on legal relationships, a distinction could not be made between single-parent households and cohabitating or step families where only one residing parent was the child’s legal parent. Information on reasons for child–parent separation was lacking. Antisocial behaviors in children might also have been a major reason for parental separation. Additionally, the study findings may not be generalizable to other countries, although it is likely that similar patterns of elevated risk would be observed in other Western cultures.

Conclusions

This national cohort study augments existing published evidence that separation from a parent during childhood is strongly associated with elevated risk for later violent criminality. Child–parent separation may be a marker for a range of adversities and dysfunctionalities in the household, especially in families experiencing multiple transitions. Violence prevention should therefore include strategies to tackle related household adversities, for which promoting a stable home environment is one salient aspect. Professional counseling and mediation services, as well as intervention programs to promote positive parenting behavior and to tackle any adverse impact of separation, can be beneficial for those facing relationship and family difficulties. For example, the New Beginnings Program in the U.S. was established to promote positive adaptation and children’s resilience following parental divorce or separation (https://reachinstitute.asu.edu/programs/new-beginnings), and has been reported to have a positive impact on parenting skills and youth outcomes, including improved mental health and reduced criminal justice system costs.50, 51, 52 Similarly, the online coping skills program Children of Divorce–Coping with Divorce (http://familytransitions-ptw.com/CoDCoD/parents/) has been shown to be effective in reducing youth mental health problems.53 Children who are separated from both parents during adolescence are especially vulnerable. Future research examining between-sibling differential exposure to child–parent separation would control for some of the unobserved familial risk factors, and thereby help to elucidate the links between child–parent separation and later violent criminality risk. Factors such as residential mobility and child–parent attachment could also be examined as possible mediators of the link between child–parent separation and subsequent violent offending risk.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a European Research Council grant awarded to Roger T. Webb (ref. no.: 335905). The funder had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Authors’ contributions: Professor Pedersen, Professor Webb, Mr. Astrup, and Ms. Antonsen had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Mok wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors helped with acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and contributed to subsequent revisions; and reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. Mok, Astrup, Carr, Webb, and Pedersen contributed to the study concept and design. Astrup and Antonsen performed the statistical analysis. Webb obtained funding. Pedersen and Webb provided administrative, technical or material support.

Key findings from this manuscript were presented by: Prof. Roger T. Webb on December 1, 2016, at the 18th European Psychiatric Association Section Meeting in Epidemiology & Social Psychiatry, Gothenburg, Sweden (oral presentation); Dr. Pearl LH Mok on September 6–8, 2017 at the Society for Social Medicine 61st Annual Scientific Meeting, Manchester, England (poster presentation); and Prof. Roger T. Webb on October 18–20, 2017, at the International Federation of Psychiatric Epidemiology conference, Melbourne, Australia (poster presentation).

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Supplemental materials data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.008.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Copen C.E., Daniels K., Vespa J., Mosher W.D. First marriages in the United States: data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Report. 2012;49:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eurostat. Marriage and divorce statistics. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Marriage_and_divorce_statistics. Accessed November 27, 2017.

- 3.Kennedy S., Bumpass L. Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: new estimates from the United States. Demogr Res. 2008;19:1663–1692. doi: 10.4054/demres.2008.19.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavanagh S.E. Family structure history and adolescent adjustment. J Fam Issues. 2008;29(7):944–980. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perales F., Johnson S.E., Baxter J., Lawrence D., Zubrick S.R. Family structure and childhood mental disorders: new findings from Australia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(4):423–433. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1328-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Astrup A., Pedersen C.B., Mok P.L., Carr M.J., Webb R.T. Self-harm risk between adolescence and midlife in people who experienced separation from one or both parents during childhood. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paksarian D., Eaton W.W., Mortensen P.B., Merikangas K.R., Pedersen C.B. A population-based study of the risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder associated with parent-child separation during development. Psychol Med. 2015;45(13):2825–2837. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demuth S., Brown S.L. Family structure, family processes, and adolescent delinquency: the significance of parental absence versus parental gender. J Res Crime Delinq. 2004;41(1):58–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fergusson D.M., Horwood L.J., Lynskey M.T. Parental separation, adolescent psychopathology, and problem behaviors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(8):1122–1131. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199410000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fergusson D.M., Boden J.M., Horwood L.J. Exposure to single parenthood in childhood and later mental health, educational, economic, and criminal behavior outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(9):1089–1095. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sauvola A., Koskinen O., Jokelainen J., Hakko H., Järvelin M.R., Räsänen P. Family type and criminal behaviour of male offspring: the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48(2):115–121. doi: 10.1177/002076402128783163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeder R.D., Osgood A.K., Oghia M.J. Family transitions and juvenile delinquency. Sociol Inq. 2010;80(4):579–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682x.2010.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skarðhamar T. Family dissolution and children's criminal careers. Eur J Criminol. 2009;6(3):203–223. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theobald D., Farrington D.P., Piquero A.R. Childhood broken homes and adult violence: an analysis of moderators and mediators. J Crim Justice. 2013;41(1):44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper C.C., McLanahan S.S. Father absence and youth incarceration. J Res Adolesc. 2004;14(3):369–397. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jablonska B., Lindberg L. Risk behaviours, victimisation and mental distress among adolescents in different family structures. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(8):656–663. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fomby P., Cherlin A.J. Family instability and child well-being. Am Sociol Rev. 2007;72(2):181–204. doi: 10.1177/000312240707200203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilomäki E., Viilo K., Hakko H. Familial risks, conduct disorder and violence: a Finnish study of 278 adolescent boys and girls. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(1):46–51. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antecol H., Bedard K. Does single parenthood increase the probability of teenage promiscuity, substance use, and crime? J Popul Econ. 2007;20(1):55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen C.B., Gøtzsche H., Møller J.O., Mortensen P.B. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53(4):441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen M.F., Greve V., Høyer G., Spencer M. The Principal Danish Criminal Acts. 3rd ed. DJØF Publishing; Copenhagen: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danmarks Statistik . Danmarks Statistiks trykkeri; Copehagen: 1991. IDA - en Integret Database for Arbejdsmarkedsforskning. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laird N., Olivier D. Covariance analysis of censored survival data using log-linear analysis techniques. J Am Stat Assoc. 1981;76(374):231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen P., Borgen O., Gill R., Kieding N. Corrected. 1st ed. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1997. Statistical Models Based on Counting Processes. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carstensen B. Demography and epidemiology: practical use of the Lexus diagram in the computer age. Who needs the Cox-model anyway? Institute of Public Health, University of Copenhagen. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Finnish Statistical Society, 23-24 May 2005; revised December 2005. http://publichealth.ku.dk/sections/biostatistics/reports/2006/rr-06-2.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2017.

- 26.Breslow N.E., Day N.E. No. 82. IARC Scientific Publications; Lyon: 1987. (Statistical Methods in Cancer Research Volume II—The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clayton D., Hills M. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1993. Statistical Models in Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothman J., Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carstensen B. Example and programs for splitting follow-up time in cohort studies. Institute of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, 2007. http://staff.pubhealth.ku.dk/~bxc/Lexis/.

- 30.Macaluso M. Exact stratification of person-years. Epidemiology. 1992;3(5):441–448. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christoffersen M.N., Soothill K., Francis B. Violent life events and social disadvantage: a systematic study of the social background of various kinds of lethal violence, other violent crime, suicide, and suicide attempts. J Scand Stud Criminol Crime Prev. 2007;8(2):157–184. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elonheimo H., Sourander A., Niemelä S., Helenius H. Generic and crime type specific correlates of youth crime: a Finnish population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(9):903–914. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krug E.G., Dahlberg L.L., Mercy J.A., Zwi A.B., Lozano R., editors. World Report on Violence and Health. WHO; Geneva: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fomby P., Sennott C.A. Family structure instability and mobility: the consequences for adolescents’ problem behavior. Soc Sci Res. 2013;42(1):186–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahlin H., Kuja-Halkola R., Bjureberg J. Association between deliberate self-harm and violent criminality. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):615–621. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fergusson D.M., Horwood L.J., Lynskey M.T. Family change, parental discord and early offending. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1992;33(6):1059–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daryanani I., Hamilton J.L., Abramson L.Y., Alloy L.B. Single mother parenting and adolescent psychopathology. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016;44(7):1411–1423. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0128-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galloway T.A., Skardhamar T. Does parental income matter for onset of offending? Eur J Criminol. 2010;7(6):424–441. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogilvie C.A., Newman E., Todd L., Peck D. Attachment & violent offending: a meta-analysis. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19(4):322–339. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savage J. The association between attachment, parental bonds and physically aggressive and violent behavior: a comprehensive review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19(2):164–178. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavanagh S.E., Huston A.C. The timing of family instability and children’s social development. J Marriage Fam. 2008;70(5):1258–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webb R.T., Pedersen C.B., Mok P.L. Adverse outcomes to early middle age linked with childhood residential mobility. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(3):291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong M., Anda R.F., Felitti V.J. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(7):771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blum J., Ireland M., Blum R.W. Gender differences in juvenile violence: a report from Add Health. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32(3):234–240. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duke N.N., Pettingell S.L., McMorris B.J., Borowsky I.W. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e778–e786. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flannery D.J., Singer M.I., Wester K. Violence exposure, psychological trauma, and suicide risk in a community sample of dangerously violent adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):435–442. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frisell T., Lichtenstein P., Långström N. Violent crime runs in families: a total population study of 12.5 million individuals. Psychol Med. 2011;41(1):97–105. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burt S.A., Barnes A.R., McGue M., Iacono W.G. Parental divorce and adolescent delinquency: ruling out the impact of common genes. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(6):1668–1677. doi: 10.1037/a0013477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Onofrio B.M., Turkheimer E., Emery R.E. A genetically informed study of marital instability and its association with offspring psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(4):570–586. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herman P.M., Mahrer N.E., Wolchik S.A., Porter M.M., Jones S., Sandler I.N. Cost-benefit analysis of a preventive intervention for divorced families: reduction in mental health and justice system service use costs 15 years later. Prev Sci. 2015;16(4):586–596. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0527-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sandler I., Ingram A., Wolchik S., Tein J.Y., Winslow E. Long-term effects of parenting-focused preventive interventions to promote resilience of children and adolescents. Child Dev Perspect. 2015;9(3):164–171. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolchik S.A., Sandler I.N., Tein J.Y. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families: effects on mental health and substance use outcomes in young adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(4):660–673. doi: 10.1037/a0033235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boring J.L., Sandler I.N., Tein J.Y., Horan J.J., Vélez C.E. Children of divorce-coping with divorce: a randomized control trial of an online prevention program for youth experiencing parental divorce. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(5):999–1005. doi: 10.1037/a0039567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material