Abstract

Commercially available ocular drug delivery systems are effective but less efficacious to manage diseases/disorders of the anterior segment of the eye. Recent advances in nanotechnology and molecular biology offer a great opportunity for efficacious ocular drug delivery for the treatments of anterior segment diseases/disorders. Nanoparticles have been designed for preparing eye drops or injectable solutions to surmount ocular obstacles faced after administration. Better drug pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, non-specific toxicity, immunogenicity, and biorecognition can be achieved to improve drug efficacy when drugs are loaded in the nanoparticles. Despite the fact that a number of review articles have been published at various points in the past regarding nanoparticles for drug delivery, there is not a review yet focusing on the development of nanoparticles for ocular drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye. This review fills in the gap and summarizes the development of nanoparticles as drug carriers for improving the penetration and bioavailability of drugs to the anterior segment of the eye.

Keywords: nanoparticles, anterior segment of the eye, ocular barriers, poly(alkyl cyanoacrylate), polysaccharide, polyester, EUDRAGIT®, lipid, dendrimer, contact lenses

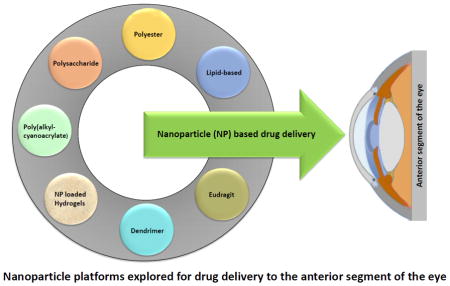

Graphical Abstract

Nanoparticle platforms explored for drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye

1. Introduction

The eye is a delicate and very complicated organ having two main anatomical segments: the anterior segment and the posterior segment (Figure 1). The anterior segment is a part of the eyeball that is anterior to the lens and mainly consists of the cornea, conjunctiva, iris, lens, ciliary body, and the anterior portion of the sclera. It is further divided into two chambers, the anterior (between the posterior surface of the cornea and iris) and posterior (between the posterior surface of the cornea and the iris) chambers, which are connected by the opening of the pupil and filled with aqueous humor secreted by ciliary processes. The aqueous humor provides nutrients for lens and cornea, maintains intraocular pressure, and is replaced several times a day [1]. The diseases/disorders occurring in the anterior segment include cataracts, dry eye, congenital and developmental abnormalities, inflammatory diseases, infectious diseases, hereditary and degenerative diseases, glaucoma, tumors, injury, trauma, and ocular manifestations of systemic diseases. Clinically, these anterior segment diseases/disorders are more often treated by using eye drops or ointments. However, the efficacy of the eye drop and ointment treatments is low due to the existence of ocular barriers including the cornea and conjunctival barriers covering the ocular surface, and tear drainage (Figure 1) [1, 2]. Nevertheless, local therapy via topical and periocular administrations is more favorable over therapies via systemic administration such as oral and intravenous administrations to manage ocular diseases. The first reason is that the eye has much fewer blood vessels and less blood flow than the whole body blood circulatory system so that the amount and rate of drugs to be cleared through local eye administration is much less than through systemic administration. The second reason is due to the presence of blood-aqueous barrier, which limits the drug penetration from the systemic circulation into the anterior segment of the eye. Recent advances in nanoparticles offer a great opportunity for efficient local delivery of drugs to the anterior segment. The advantages of nanoparticles include enhancing drug permeability across the blood-aqueous barrier and cornea, prolonging drug contact time with ocular tissues, delivering drugs to a specific tissue site in a controlled manner, protecting drugs from degradation and metabolism to enhance drug stability, sustaining drug release for weeks to months, having low to no toxicity and side effects, maintaining long shelf-life, and needing no reconstitution and no surgical removal. In this review, we will discuss the routes of administration and ocular barriers and summarize the up-to-date development of polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye.

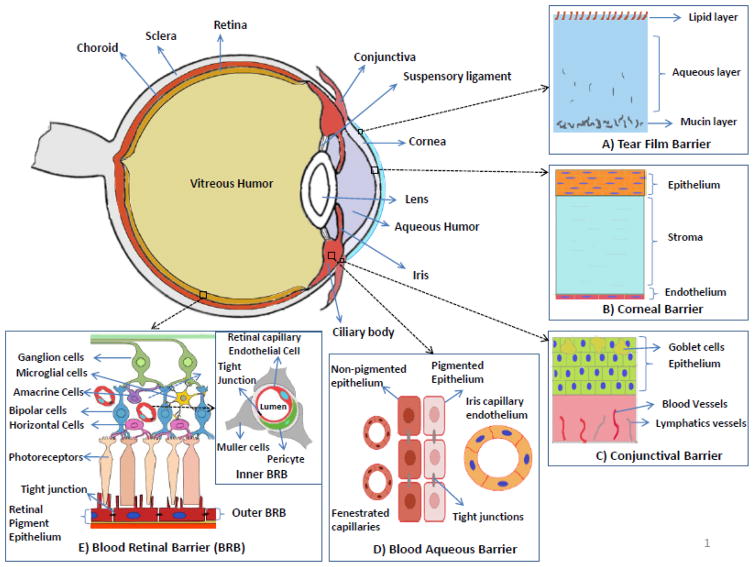

Fig. 1.

Structure of the anterior segment of the eye and ocular barriers for drug delivery. A) Tear film barrier: Main components of the tear film include mucins, water and lipid, and acts a defensive barrier to the foreign-object access to the cornea and conjunctiva. B) Corneal barrier: avascular and comprised of three major layers which are epithelium (multiple layers stacked on each other), stroma and endothelium (single layer). Acts as a barrier preventing the drug absorption from the lacrimal fluid into the anterior chamber after the topical administration. C) Conjunctival barrier: mucous membrane consisting of conjunctival epithelium (2–3 layers thick), and an underlying vascularized connective tissue. Acts a barrier to the topically administered drugs and relatively in-efficient compared to the corneal barrier. D) Blood-aqueous barrier: located in the anterior segment of the eye. Formed by the capillary endothelium in the iris, and the ciliary epithelium which both contain tight junctions. The barrier is relatively inefficient compared to the blood retinal barrier and small molecules can reach the aqueous humor by permeation through fenestrated capillaries in the ciliary processes. E) Blood-retinal barrier (BRB): located in the poster segment of the eye. Formed by the retinal pigment epithelium (outer BRB) and the endothelial membrane of the retinal blood vessels (inner BRB), both contain tight junctions. The tight junctions restrict the entry of the drugs from the blood (systemic) into the retina/aqueous humor.

2. Routes of administration and ocular barriers for delivering drugs to the anterior segment

There are four routes of administration for drugs to reach the anterior segment of the eye: topical, intracameral, subconjunctival, and systemic routes. Depending on the routes of administration, one or more ocular barriers need to be circumvented for drugs to reach the disease/action sites in the anterior segment of the eye. Table 1 lists the four routes of administration and their associated advantages and limitations. Figure 1 illustrates the structure of the anterior segment of the eye and ocular barriers for drug delivery. In the following, we will discuss the details of the four routes of administration and related ocular barriers.

Table 1.

Administration routes for delivering drugs to the anterior segment of the eye.

| Route of administration | Advantages | Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Topical | simple, convenient, self-administrable and noninvasive administration; avoiding the blood-aqueous barrier; no first-pass metabolism | short contact time of drug on the ocular surface; low efficiency and low bioavailability due to corneal and conjunctival barriers, tear clearance, and nasolacrimal drainage |

| Intracameral | avoiding the cornea, conjunctiva and blood-aqueous barrier; no first-pass metabolism; high efficacy; high bioavailability | usually need reconstitution; correct dosing and preparation are critical. |

| Subconjunctival | easy and minimally invasive administration; avoiding the cornea and blood-aqueous barrier; no first-pass metabolism; good efficacy; good bioavailability; sustained release | conjunctival blood and lymphatic clearance |

| Systemic | convenient to deliver a large dose of the drug; noninvasive; avoiding the cornea | low bioavailability due to systemic absorption and blood-aqueous barrier; first-pass metabolism |

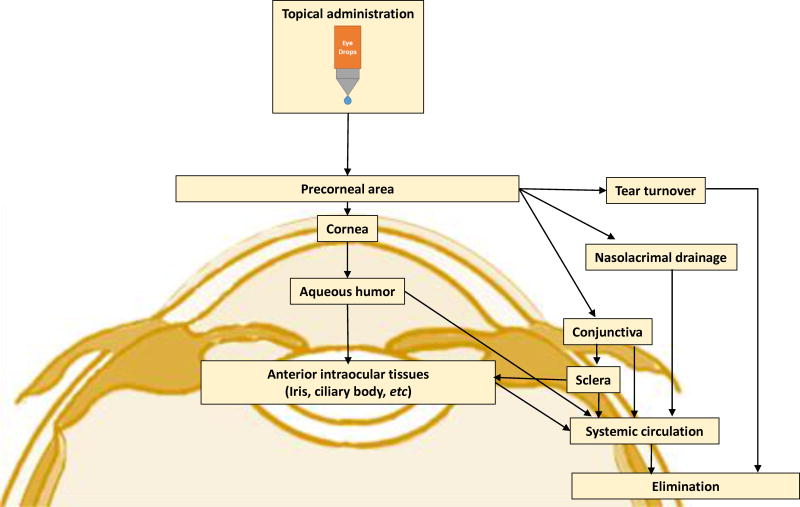

Topical administration is the simplest, most convenient, self-administrable, non-invasive, and most dominant drug administration route for the management of anterior segment diseases/disorders. It is a local drug delivery method, avoiding the blood–aqueous barrier, and the side effects and first-pass metabolism that may occur in some systemically administrated drugs. Drugs administrated through the topical route are usually formulated into eye drops. Depending on the formulation and the drugs’ physiochemical characteristics, drugs can reach various external (cornea, conjunctiva sclera) and internal (iris, ciliary body, aqueous humor, vitreous humor, retina) sites in the eye after topical instillation (Figure 2) [3, 4]. However, only 1–7% of the administered drugs can reach the aqueous humor due to the tear film, and cornea and conjunctiva barriers [5–7]. The tear film is the first obstacle faced for topically administered drugs. It consists of three layers: an outermost lipid layer, a thicker aqueous middle layer and an innermost mucin layer (Figure 1). The tear film is created by tears which are composed of water, electrolytes, and many different proteins that work together to promote healing and fight infection. A human tear has a total volume of about 7~30 μL with a turnover rate of 0.5~2.2 μL/min, and tear film has a rapid restoration time of 2~3 min [8]. Due to the fast turnover rate and time of tear film, the topically administered eye drops are quickly washed away and drained into nasolacrimal duct after instillation. The cornea is the second ocular barrier limiting the penetration of exogenous substances into the eye. It is composed of five layers: epithelium, Bowman’s membrane, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium (Figure 1). The layers which form substantial barriers to drug penetration are epithelium, stroma, and endothelium. The superficial corneal epithelium is composed of multiple layers of stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelial cells. It limits the permeation of hydrophilic drugs through the cornea due to the hydrophobicity of the epithelium and the presence of tight junctional proteins between the corneal epithelial cells [3, 9]. The inner layer next to the corneal epithelium is the stroma. The stroma is comprised of glycosaminoglycans and collagen fibrils in lamellar structures, and it has a hydrophilic environment. It restricts the penetration of lipophilic drugs through the cornea [3]. The innermost layer of the cornea is monolayer corneal endothelium composed of hexagonal-shaped endothelial cells. This corneal endothelium is leakier than the epithelium and allows the penetration of macromolecules into the aqueous humor on the other side [3]. Overall, the cornea acts as a physical barrier to hydrophilic drugs due to the superficial corneal epithelial layers, and to lipophilic drugs due to the stroma. Besides the cornea route, topically administered drugs can be absorbed into the anterior segment through a non-cornea route: the conjunctiva/sclera pathway, as the conjunctiva has a larger surface area than the cornea (17 vs. ~ 1 cm2) [5, 6, 10, 11]. Conjunctiva is a rate-limiting barrier for permeation of water-soluble drugs [12, 13] due to rapid drug elimination by conjunctival blood and lymphatic flow. After escaping from conjunctival elimination, drugs penetrate through the sclera to reach the anterior segment (trans-scleral pathway). The sclera has large surface area and relatively high permeability than the cornea, and the trans-scleral permeation mainly depends on the size of the drug molecules rather than their lipophilicity [3, 14, 15].

Fig. 2.

Flow chart presenting the drug pathway into the eye after topical application.

Intracameral administration is a method for direct injection of drugs into the anterior chamber in the anterior segment of the eye [16]. It is a local drug delivery method, avoiding the side effects and the first-pass metabolism that may occur in some systemically administrated drugs. It also avoids the cornea, conjunctiva, and blood-aqueous barriers. Therefore, intracameral injection can deliver drugs to the anterior segment relatively easily with high efficiency and was expected to achieve 300 to 600 times more aqueous humor drug level than topical application [17, 18]. After intracameral injection, the mechanism for drugs to reach tissues in the anterior segment is via diffusion and the bulk flow of aqueous humor. In general, the literature supports the safety of intracamerally injected antibiotics such as vancomycin, moxifloxacin, and cephalosporins [18–20]. In addition, the intracameral injection technique was shown to be useful in the off-label use of anti-vascular endothelial growth (anti-VEGF) agents and triamcinolone acetonide for the management of neovascularization in the treatment of neovascular glaucoma and endothelial allograft rejection after penetrating keratoplasty, respectively [21, 22]. However, intracameral antibiotics usually need reconstitution including dilution and other special preparations which require sterilization, preservative-free, and proper concentration and dose. If incorrect dosing and preparation occur, corneal endothelial toxicity and toxic anterior segment syndrome become big concerns [18, 20].

Subconjunctival administration places drugs into the subconjunctival space around the outside of the sclera, and then drugs penetrate through the sclera and reach the anterior segment. It is a minimally invasive and effective route for delivering drugs to the anterior segment, avoiding the cornea and blood–aqueous barriers, and the side effects and first-pass metabolism that may occur in some systemically administrated drugs. It is a local drug delivery method, and can offer sustained drug delivery depending on formulations or devices. However, the subconjunctival route has the limitation of possible loss of drugs to the systemic circulation due to the drainage via the conjunctival blood and lymphatic vessels [14, 23].

Systemic administration can deliver drugs to the anterior segment, but with low bioavailability for conventional ophthalmic formulations such as solutions and suspensions, due to the presence of the blood–aqueous barrier. The two layers that comprise the blood-aqueous barrier (BAB) are the endothelium of the iris/ciliary blood vessels and the nonpigmented epithelium of the ciliary body (Figure 1) [1, 3]. Because of the presence of the tight junctional complexes in both these layers, BAB restricts the penetration of drug molecules from the blood into the aqueous humor [3, 24]. In order to achieve therapeutic levels of drugs in the aqueous humor, high doses are necessary, and high doses can cause adverse systemic side effects so that the systemic administration route is rarely used to treat anterior segment disease/disorders. For clarification, we would like to specifically mention that the term bioavailability in this review means the rate and extent of drug available at the target anterior ocular site such as tear fluid, corneal or conjunctival tissue, aqueous humor, iris, etc. after drug administration [25–28]. Three pharmacokinetics (PK) parameters that are commonly used for assessing ocular bioavailability are: Cmax, the maximum drug concentration achieved at target ocular site; Tmax, the time required to achieve the Cmax; and AUC, the area under curve (drug concentration in ocular tissue vs time curve) [27, 29–31]. AUC is the most commonly used parameter to describe ocular bioavailability [30], and noted as AUC(0-t) and AUC(0-∞) for time 0 to t and 0 to infinity, respectively [31].

3. Nanoparticles for drug delivery to the anterior segment

As discussed above, the ocular bioavailability of topically administrated drugs is limited due to several factors such as small anatomical space, baseline and reflex lachrymation tear drainage, metabolic degradation of the drugs, and other anatomical and physiological barriers in the eye [7, 24, 32–35]. Appropriate concentrations of the drug are needed at targeted sites in the eye to achieve therapeutic effects of the drugs. To obtain the appropriate concentrations, frequent instillation of eye drops containing the drugs is the common method. However, the frequent dosing method can cause toxic side effects and damage to ocular tissues [3]. It is important and necessary to develop technologies that can deliver drugs to the targeted sites in the eye with low or no frequent dosing. Therapeutic targets for drugs to treat anterior eye segment - related diseases can be located in extra- or intraocular tissues [36]. Based on the therapeutic target areas, the goals of drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye can be sub-divided into two categories, a) to improve the bioavailability the drugs at extraocular tissues to alleviate the signs and symptoms caused by ocular surface inflammatory disorders of cornea and conjunctiva, such as dry eye syndrome and allergic diseases; and b) to enhance the bioavailability of the drugs in the intraocular tissues to treat infections and complex, vision-threatening diseases such as glaucoma or intraocular inflammation (uveitis). Nanoparticles have large surface areas and can be made of many types of materials with multifunctional surface groups. These materials hold great promise in helping drugs to reach targeted sites to achieve the stated two purposes of drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye [2, 37–44]. The reasons are that nanoparticles can be entrapped in the ocular mucus layer and then bioadhesive polymer chains/materials that form the nanoparticles can intimately interact with the extraocular tissues to prolong the residence time of drugs loaded in the nanoparticles and reduce drug drainage and thus improve the bioavailability the drugs at extraocular tissues [33]. Furthermore, nanoparticles can also penetrate through ocular surface tissues to deliver encapsulated drugs to intraocular tissues so that improved bioavailability of the drugs at the intraocular tissues can be achieved [45]. The penetration depends on the size, charge, architecture, surface chemistry, and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of the nanoparticulate systems [46–48]. Table 2 summarizes some of the important characteristics/properties of the nanoparticles and corresponding characterization techniques used to determine those properties.

Table 2.

Summary of the techniques used for physicochemical and in vitro and in vivo characterizations of nanoparticles for anterior ocular delivery.

| Property | Characterization Method |

|---|---|

| Yield | Gravimetric [53] |

| Particle size/morphology | Dynamic light scattering [25, 53, 91, 95, 118, 119, 123, 142, 150, 171, 174, 178, 185, 193, 194, 210, 213, 246–255] |

| Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [30, 91, 102, 113, 118, 119, 174, 178, 191, 193, 194, 208, 248, 256–260] | |

| Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)[117, 119, 218, 251, 253, 261, 262] | |

| Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope [210] | |

| Thermomicroscopy [263] | |

| Atomic microscopy [228] | |

| Zeta potential | Laser Doppler anemometry (LDA)/electrophoretic mobility [25, 95, 119, 123, 142, 174, 185, 248, 249, 252–255] |

| Chemical characterization | Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy [91, 95, 113, 117, 142, 208, 259, 261, 263–265] |

| Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [203, 208, 259, 264] | |

| Mass spectrometry [266] | |

| Elemental analysis [251, 264] | |

| Solid-state characterization | Infrared spectrophotometry [142, 261, 263] |

| X-ray diffractometry [91, 113, 142, 171, 263, 267] | |

| Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) [91, 95, 113, 142, 171, 174, 191, 193, 218, 259, 263, 267] | |

| Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) [261] | |

| Molecular weight characterization | Size exclusion chromatography [203] |

| Surface tension | Tensiometer [203] |

| Viscosity of solution | Rheometer/viscometer [185, 203, 260, 265, 268] |

| Drug loading and Entrapment efficiency | HPLC [25, 89, 171, 174, 193, 194, 208, 221, 249, 250, 254] |

| UV-Vis spectroscopy [91, 102, 113, 117–119, 178, 210, 253, 255, 258, 260, 262, 264, 267] | |

| Liquid scintillation counter for radio labelled[123] | |

| bioassay [252] | |

| GPC and UV [213] (drug separated by dialysis or centrifugation or membrane filtration) | |

| In vitro drug release | Sample and Separate [25, 95, 117, 119, 123, 142, 150, 210, 269] |

| Dialysis system [102, 113, 150, 178, 191, 193–195, 208, 246–249, 253, 255, 259–263, 265, 267] | |

| Diffusion cell [171, 213, 268] | |

| (drug analysis by spectrofluorometric or UV-Vis or HPLC or LC-MS/MS or liquid scintillation counting) | |

| Drug stability | HPLC [208, 210, 218, 265, 270] |

| Enzyme stability | Incubation with Mucin ad Lysozyme and analyze for particle size, Zeta and drug leakage [117, 256] |

| Incubation in simulated tear fluid and analyze for particle size [252] | |

| Storage stability | Incubation at appropriate conditions and analyze for particle size, poly-dispersity index, zeta potential and/or drug leakage [30, 142, 179, 208, 255, 261, 262, 265, 271] |

| In vitro cytotoxicity | MTT colorimetric assay or XTT colorimetric assay [102, 230, 252] [30] |

| SEM [256] | |

| Neutral red (NR) assay[174] | |

| Erythrocyte morphology & Hemolysis/spectrophotometer[208] | |

| Resazurin assay[258] | |

| In vitro irritancy test | Hen’s Egg Test - Chorioallantoic Membrane (HET-CAM) test [113, 178, 218, 258, 259, 262, 267, 268] |

| Mucoadhesive capacity | Mucin-particle method (incubating with mucin-centrifugation-analyze free mucin by colorimetric method) [91, 113, 185, 258, 259, 267] |

| Ex vivo study by fluorescence microscopy [117] | |

| In vitro ocular permeability | Cell Monolayers – Transwell Inserts [171, 174] (drug analysis by HPLC or LC-MS/MS) |

| Ex vivo ocular permeability | Excised cornea and a diffusion apparatus [30, 178, 191, 193–195, 213, 254] (drug analysis by HPLC or LC-MS/MS) |

| Ex vivo tissue hydration | Gravimetric -Wet and dry weight (desiccation) [178, 213] |

| Cellular internalization or uptake (in vitro or ex vivo) | Immunofluorescence Assays by confocal laser scanning microscope [113, 174, 178, 218, 247, 252, 256, 272] |

| Spectrofluorimetry [256, 272] | |

| Fluorescence microscopy [230, 272] | |

| Flow cytometry [128] | |

| In vivo ocular tolerability | Modified Draize Test using a slit-lamp[25, 142, 193, 273] |

| Histopathology [30, 150, 194] | |

| Slit lamp examination of clinical observations and ocular reactions (such as swelling and redness, conjunctival chemosis, discharge, iris and corneal lesions)-ocular irritation scoring testing system [150, 185, 203, 208, 213, 252, 254, 255, 272] | |

| In vivo precorneal retention | HPLC [254] |

| LC–MS/MS analysis [268, 274] | |

| Slit-lamp examination of fluorescence or Fluorescence imaging system using dye [191, 193, 195, 203, 208, 213, 250] | |

| SEM [261] | |

| Gamma scintigraphy[113, 179, 267] | |

| In vivo ocular drug distribution/ocular bioavailability | Polarization fluoroimmunoanalysis [246] |

| Radio labelled - liquid scintillation counter [118, 123, 248] | |

| HPLC [25, 178, 191, 193, 194, 249, 250, 263, 273] | |

| UV-Vis [261] | |

| single photon emission computed tomography image analysis [118] | |

| microdialysis [195] |

The penetration mechanisms for nanoparticles into the interior segment of the eye have not been deeply studied; however, the commonly accepted endocytosis mechanism in explaining nanoparticles’ tissue penetration was also observed by Robinson and his colleagues when they used fluorescence microscopy to study the penetration of poly(butyl cyanoacrylate) nanoparticles across the ex vivo rabbit cornea and conjunctiva [46, 49–54]. The most commonly used in vitro and ex vivo models for evaluating the corneal penetration have been summarized by Agarwal et al [55]. Additionally, nanoparticles can protect drugs from degradation and sustain release of drugs which can also increase the bioavailability of the drugs in both extra- and intraocular tissues.

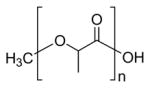

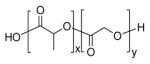

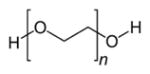

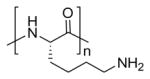

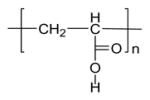

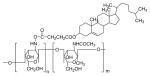

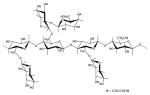

In the following discussions, we will systematically review the progress and challenges in the development of polymeric nanoparticles and their composites with hydrogel matrix for delivering drugs to the anterior segment. These polymeric nanoparticles are made of poly(alkyl cyanoacrylate), polysaccharides, polyesters, EUDRAGIT® polymers and lipids, whose chemical structures are illustrated in Tables 2–5. There are other strategies such as imprinted contact lenses [56], vitamin E based contact lenses [57], and nanowafer-based systems [58–61] that have been used for extended ocular drug delivery to the anterior segment; however, these strategies are not discussed in this review as the main focus of this review is nanoparticles rather than other systems for drug delivery to the anterior segment.

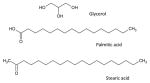

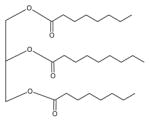

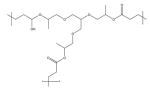

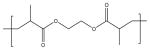

Table 5.

Chemical structures of lipids used for drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye.

| Name | Chemical Structures |

|---|---|

| Thiolated PEG stearate (cysteine-polyethylene glycol monostearate) |

|

| Compritol 888 ATO (Behenoyl polyoxyl-8 glycerides NF) or Docosanoic acid,1,2,3-propanetriyl ester |

|

| Precirol ATO 5 (Glycerol Palmito-Stearate) |

|

| Gelucire 44/12 (Lauroyl polyoxyl-32 glycerides NF) | N/A |

| Miglyol 812 |

|

| Dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine |

|

3.1. Poly(alkyl cyanoacrylate) nanoparticles

Poly(alkyl cyanoacrylate) (PACA, Table 2) nanoparticles emerged in the early 1980s and have been extensively studied for drug delivery to the brain and eye [62]. PACA nanoparticles were prepared through emulsion and interfacial polymerizations from monomers, or nanoprecipitation and emulsion-solvent evaporation from presynthesized PACA polymers [62]. Due to the excellent adhesive properties of alkyl cyanoacrylates, PACA nanoparticles were the first nanoparticles investigated for topical ocular drug delivery to the eye [54, 63–68]. Poly(2-hexyl cyanoacrylate) nanoparticles were found to have 4-fold greater accumulation in inflamed albino rabbit eye tissues than healthy tissue. [63, 66]. Hydrophobic drugs such as pilocarpine [64] and acyclovir [69], and hydrophilic drugs such as betaxolol hydrochloride [67] and amikacin sulfate [68], were successfully loaded into PACA nanoparticles. Poly(butyl cyanoacrylate) PBCA nanoparticles improved myotic response to pilocarpine in albino rabbits [64]; increased the concentration of amikacin sulfate in the cornea and aqueous humor in the presence of dextran 70000 [68]; and enhanced the absorption of positively charged betaxolol hydrochloride with decreasing its surface zeta potential and the subsequent antiglaucoma activity of betaxolol hydrochloride, depending on the amount of the drug released [67]. Table 6 summarizes various drug-loaded PACA nanoparticles and their characteristics. Since PACA nanoparticles were found to cause cell lysis and cornea damage in 90’s [54, 62], PACA nanoparticles have been seldom investigated for ocular drug delivery although improved ocular toleration of PACA nanoparticles was observed in the six-hour tolerability study by coating PACA nanoparticles using poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) polymers [69]. Researchers switched to other more biocompatible polymers for the development of polymeric nanoparticles for ocular delivery as discussed below.

Table 6.

Examples of drug-loaded PBCA nanoparticles.

| Primary Polymer |

Other Component |

Fabrication Method |

Drug Encapsulate d |

Size (nm) |

Zeta Potentia l (mV) |

Encapsulatio n Efficiency (%) |

In Vitro Releas e |

In Vivo Observation s |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBCA | pluronic F68 | nanoprecipitation | pilocarpine | 98±4 | - | ~10–60 | 10 h | nanoparticle-drug adsorbates showed prolonged myosis (rabbit) | [275] |

| PBCA | dextran 70k; dextran sulfate; n-acetylglucosamine | nanoprecipitation | betaxolol HCl | 220 to 241 | −0.5 to +12.5 | ~25–70 | ~40% in 2h | increased reduction in IOP (rabbit) compared to commercial drops | [276] |

| PBCA/poly(ethylene glycol) coating | pluronic F68; hydroxypropyl-b-cyclodextrin; | emulsion polymerization | acyclovir | 190 to 450 | −12.2 to −25.9 | - | ~40–65% in 15 min; 60–80% in 7 h | 25-fold higher AUC(0–360 min) compared to free drug suspension (rabbit) | [69] |

| PBCA | dextran 70k; Synperonic F68; sodium lauryl sulfate | nanoprecipitation | amikacin sulfate | 83.75 to 453.3 | −0.26 to −2.75 | - | ~70% in 3 h | achieved at least 3-fold higher drug concentrations of drug in aqueous humor than the control solution (rabbit) | [68] |

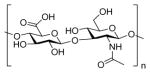

3.2. Polysaccharide nanoparticles

Polysaccharides are long chain carbohydrate molecules having a large number of reactive functional groups varying in chemical composition. Their molecular weights vary widely due to the diversity of their structures and properties. Common hydrophilic functional groups present in the polysaccharides are hydroxyl, carboxyl and amino groups. These functional groups can form hydrogen bonds with mucosa to become mucoadhesive [70]. Due to the hydrogen bonds, when mucoadhesive polysaccharides are added in the eye drops, the drug’s retention time in the tear film and anterior chamber is prolonged, and the clearance of the drug is controlled by the mucus turnover rate rather than the tear turnover rate and is much slower [33, 71–78]. Besides the mucoadhesive property, nature-originated polysaccharides such as chitosan and its derivatives, alginate, hyaluronic acid, gum cordia, and carboxymethyl tamarind kernel polysaccharide (Table 3), possess other appealing properties such as acceptable biocompatibility, excellent ocular tolerance [79, 80], biodegradability [81], and ability to enhance drug membrane permeability both in vitro [82] and in vivo [83]. The combination of these properties makes polysaccharides versatile biopolymers for ocular drug delivery [71, 84–89]. Drugs such as cyclosporine A (CsA) [90], dorzolamide hydrochloride [91, 92], pramipexole hydrochloride [91], acyclovir [93], 5-flurouracil [94], carteolol [92], gatifloxacin [95], betamethasone sodium phosphate [96], gene [97], pilocarpine [98], econazole nitrate [99], natamycin [100], daptomycin [89], amphotericin B [101], celecoxib [102], timolol maleate [103, 104], fluconazole [105], sodium diclofenac [106], and tropicamide [107] were loaded into nanoparticles made of polysaccharides for ocular delivery. The release of the drugs from these hydrophilic polymer nanoparticle matrices relies on various factors such as polymer hydration, solvent penetration, drug diffusion, drug dissolution, and/or polymer erosion [95]. The discussions below detail the studies carried out on polysaccharide-based nanoparticles for drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye.

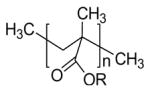

Table 3.

Chemical structures of synthetic polymers used for drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye.

| Name | Chemical Structures |

|---|---|

| Poly(alkyl-cyanoacrylate) |

|

| Poly(lactide) (PLA) |

|

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) |

|

| Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) |

|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) |

|

| Poly(L-lysine) |

|

| Carbopol® |

|

| Eudragit® RL |

|

| Poly(propoxylated glyceryl triacrylate) (poly PGT) |

|

| Poly(ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) (PEGDMA) |

|

3.2.1. Chitosan nanoparticles

Chitosan has arisen as a promising material for the improvement of drug delivery to the ocular mucosa and is most extensively studied polysaccharide. Chitosan is a cationic linear polysaccharide copolymer of 1,4-(2-amino-2-deoxy-D-glucopyranose) and 1,4-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-D-glucopyranose). The mucoadhesive nature of chitosan is related to the interaction between the positively charged amino groups of chitosan and the negatively charged residues of sialic acid in the mucus of cornea and conjunctiva [108] along with other interactions such as hydrogen bonds [109]. Another characteristic of chitosan is its penetration enhancement properties, as it can transiently open the tight junctions between cells [85, 110]. Chitosan nanoparticles are often synthesized via ionic gelation techniques using sodium tripolyphosphate as a crosslinker [80, 85, 86, 111, 112]. The benefits associated with chitosan-based nanoparticles include their ability to contact intimately with the corneal and conjunctival surfaces, and thus enhance drug delivery to external ocular tissues while minimizing the toxicity of the drugs to the internal ocular tissues and blood stream (through systemic absorption). Therefore, the chitosan-based nanoparticles show promising potential for the treatment of external ocular diseases [90]. Table 7 summarizes various drug-loaded chitosan nanoparticles and their characteristics.

Table 7.

Examples of drug-loaded chitosan nanoparticles.

| Primary Polymer |

Other Component |

Fabrication Method |

Drug Encapsulated |

Size (nm) |

Zeta Potential (mV) |

Encapsulation Efficiency (%) |

In Vitro Release |

In Vivo Observations |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | TPP | ionotropic gelation | CsA | 293±9 | +37±0.9 | 73.4 | ~65% in 1 h and ~70% in 24 h | achieved therapeutic drug levels in external ocular tissues and maintained for at least 48 h | [90] |

| Chitosan | TPP | ionotropic gelation | dorzolamide HCl; pramipexole HCl | 275 to 452 | - | - | ~60–80% in 4 h (dorzo); ~70–100% in 24 h (prami) | - | [91] |

| Chitosan | TPP; sodium alginate (in situ gel) | ionotropic gelation | dorzolamide HCl | 164±10.2 | - | 98.1 | ~50–60% in 8 h | gamma scintigraphy showed retention of formulation at the corneal surface for at least 2 h | [267] |

| Chitosan | TPP | ionotropic gelation | acyclovir | 200±30 | +36.7±1.5 | 56 to 80 | ~20% in 1 h and 90% in 24 h | - | [277] |

| Chitosan | TPP | ionotropic gelation | 5-fluorouracil | 114 to 192 | +30±4 | 8 to 34 | ~20% in 30 min and ~60% in 8 h | 3.5 fold higher AUC(0–8h) of drug in aqueous humor compared to drug solution | [94] |

| Chitosan | TPP | ionotropic gelation | carteolol | ~100 to 250 | - | ~40 to 80 | ~30% in 1 h and 80% in 24 h | gamma scintigraphy showed good spread and retention of formulation at the corneal surface compared to drug solution and prolonged IOP reduction | [113] |

| Chitosan | TPP | ionotropic gelation | ketorolac tromethamine | 108 to 257 | 16.6 to 22.9 | 34.9 to 73.48 | ~100% in 5–6 h | - | [114] |

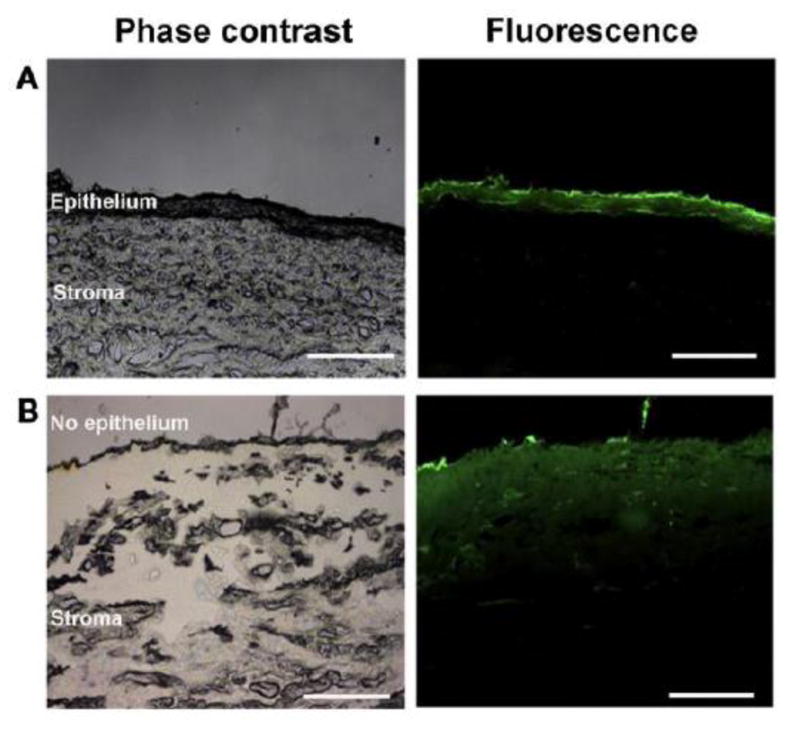

Alonso and associates first reported the study of exploring chitosan nanoparticles for delivery of drugs to the ocular surface in 2001 [90] and subsequently conducted extensive studies on chitosan nanoparticles [80, 90, 97, 112]. Synthesized chitosan nanoparticles were reported to have an average size of several hundred nanometers depending on the synthetic conditions, and an almost constant zeta potential of about +35 to +37 mV [80, 90, 93, 102, 112] which was higher than +30 mV implying that the nanoparticles were stable due to the prevention of the aggregations of the nanoparticles by the surface charges [93]. In vitro studies of chitosan nanoparticles in simulated fluids containing mucus components (mucin and lysozyme) showed that the presence of lysozyme did not compromise the stability of chitosan nanoparticles in the tear fluid. The interaction of chitosan nanoparticles with mucin did not significantly affect the viscosity of the mucin dispersion [112]. These chitosan nanoparticles were not inherently toxic to Chang conjunctival cell line at concentrations up to 2 mg·ml−1 (Figure 3) [112] and spontaneously immortalized epithelial cell line from normal human conjunctiva (IOBA-NHC) at concentrations up to 1 mg·ml−1 for up to 24 h [80]. In vivo examination of topically administrated chitosan nanoparticles in rabbits showed that the nanoparticles did not cause inflammation, tissue alteration, and damage to the epithelial layer of the rabbit cornea as shown in Figure 4 [80, 94]. Another in vivo investigation revealed that fluorescein-containing chitosan nanoparticles significantly accumulated in the rabbit cornea and conjunctiva after topically instilled to the cul-de-sac of conscious rabbits, evidenced by fluorescence intensity measurements and confocal image (Figures 5 and 6) [112] [80]. Further study of chitosan nanoparticles as a drug carrier for cyclosporine A (CsA) revealed that the nanoparticles showed a high in vitro burst release of the drug CsA (62% within 15 min) in sink conditions due to the rapid dissolutions of both the hydrophilic chitosan nanoparticles and the drug present at or close to the surface of the nanoparticles. But the authors speculated that the burst release would be minimized in vivo due to the absence of such a significant dilution process upon administration [90]. In vivo investigation of the ocular disposition of CsA showed that the therapeutic concentrations of CsA were attained in the external ocular tissues (cornea and conjunctiva) within 48 h after topical instillation of CsA-loaded chitosan nanoparticles in rabbits, while the CsA levels in the inner ocular structures (iris/ciliary body and aqueous humor), blood and plasma were negligible or undetectable. The therapeutic concentration levels in the external ocular tissues were found to be significantly higher after the instillation of CsA-loaded chitosan nanoparticles compared with the control CsA-containing chitosan (not chitosan nanoparticle) solution and aqueous CsA suspension [90]. These results demonstrated that chitosan nanoparticles could be used as carriers to enhance the therapeutic index of clinically challenging drugs such as CsA with the potential application at the extraocular level. Besides CsA, chitosan nanoparticles have also been studied for ocular delivery of other drugs such as dorzolamide hydrochloride [91, 92], pramipexole hydrochloride [91], acyclovir [93], 5-flurouracil [94], carteolol [113], and ketorolac tromethamine [114]. The in vitro release profiles of the drugs dorzolamide hydrochloride, pramipexole hydrochloride, acyclovir, 5-flurouracil, and carteolol showed a high burst release [91, 93, 94] as that of CsA [90]. The mucoadhesive strength of dorzolamide hydrochloride-, and pramipexole hydrochloride-loaded chitosan nanoparticles decreased with increasing the drug content due to the decreased amount of chitosan that was available for adhesion and the increased size of the nanoparticles [91]. Topically instilled 5-fluorouracil-loaded chitosan nanoparticles exhibited significantly higher maximum concentration Cmax (~2.7 times) and bioavailability (AUC ~3.5 times during 8 h) of fluorouracil in the aqueous humor of rabbits when compared with the drug solution alone [94]. Whole body images by gamma scintigraphy revealed that chitosan nanoparticles prolonged the retention of cateolol on the corneal and conjunctival surfaces of rabbits to significantly enhance its ocular hypotensive effect in 24 h study [92].

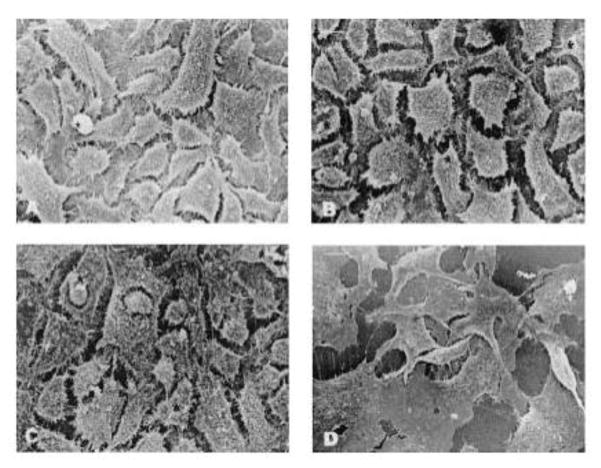

Fig. 3.

Scanning electron microphotographs of Chang cells exposed to culture medium, chitosan nanoparticles, and benzalkonium chloride for 24 h. (A) (Negative control, culture medium) Cells showing abundant microvilli and intact membrane details. (B) (Chitosan nanoparticles, 0.25 mg/ml) cells showing well-preserved morphology, an intact cell surface, and abundant microvilli, as expected for an epithelial cell. (C) (Chitosan nanoparticles, 1 mg/ml). (D) (Positive control, benzalkonium chloride) Cells were flat and showed absence of microvilli and broken membrane. Magnification ×750 (bar =15 μm). [Reprinted from “Pharmaceutical research, Chitosan nanoparticles as new ocular drug delivery systems: in vitro stability, in vivo fate, and cellular toxicity, 21.5 (2004): 803–810. De Campos, A. M., Diebold, Y., Carvalho, E. L., Sánchez, A., & José Alonso, M. c 2004 Plenum Publishing Corporation” With permission of Springer.]

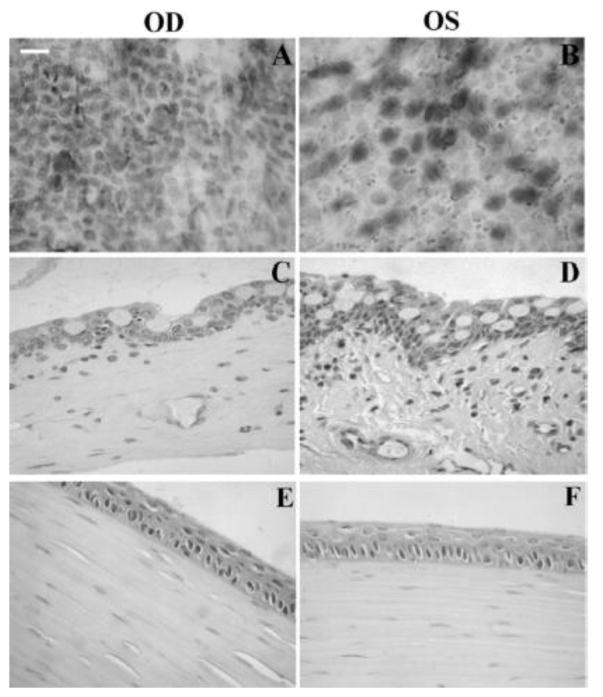

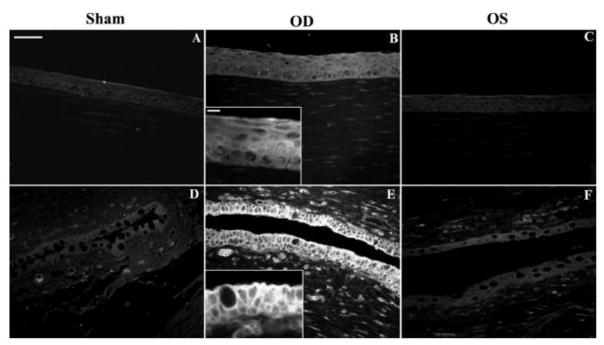

Fig. 4.

Ocular surface structures of CSNP-treated (OD) and control (OS) rabbit eyes. Rabbits were exposed to CSNPs for 24 hours. Representative conjunctival impression cytology (A, B) and conjunctival (C, D) and corneal (E, F) sections are shown. Conjunctival and corneal epithelia from both control and treated eyes displayed normal cell layers and morphology. No signs of tissue edema were observed in any structure studied after exposure to CSNPs compared with controls. Scale bar, 100 μm. [Reprinted from De Salamanca, Amalia Enríquez, et al. “Chitosan nanoparticles as a potential drug delivery system for the ocular surface: toxicity, uptake mechanism and in vivo tolerance.” Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 47.4 (2006): 1416–1425. Copyright © Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology]

Fig. 5.

Confocal fluorescence images at different levels from the rabbit corneal epithelium (5 μm sequential cross sections from the corneal surface) at 1 h postinstillation of (C) Chitosan-fluorescein nanoparticles, (B) Chitosan-fluorescein solution. (A) image of cross section of a nontreated cornea. Round fluorescent spots corresponding to the chitosan-fluorescein nanoparticles were observed inside the cells. [Reprinted from “Pharmaceutical research, Chitosan nanoparticles as new ocular drug delivery systems: in vitro stability, in vivo fate, and cellular toxicity, 21.5 (2004): 803–810. De Campos, A. M., Diebold, Y., Carvalho, E. L., Sánchez, A., & José Alonso, M. c 2004 Plenum Publishing Corporation” With permission of Springer.]

Fig. 6.

Chitosan nanoparticle in vivo uptake. Fluorescence microscopy of ocular surface structures of sham-treated (A, D), CSNP-treated (B, E), and contralateral control (C, F) rabbit eyes. Representative corneal (A–C) and conjunctival (D–F) sections are shown. No fluorescence was detected in sham control corneas (A) or conjunctivas (D). (B) Corneal epithelial cells of CSNP-treated rabbits were uniformly fluorescent. (B, inset): enlargement showing a detail of corneal epithelial fluorescence pattern. (E) Fluorescence in conjunctival epithelial cells was intense in apical cell membranes and positive along the basolateral cell membrane. (E, inset) Enlargement showing the basolateral membrane fluorescence staining in goblet and non–goblet cells. (C, F) Some fluorescence was detected in corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells from contralateral control eye (OS), although much less intense than in the treated (OD) eye. Scale bar (A–F) 50 μm; insets: 10 μm). The in vivo uptake by conjunctival and corneal epithelia was confirmed from these fluorescence microscopy images of eyeball and lids sections confirmed. [Reprinted from De Salamanca, Amalia Enrique, et al. “Chitosan nanoparticles as a potential drug delivery system for the ocular surface: toxicity, uptake mechanism and in vivo tolerance.” Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 47.4 (2006): 1416–1425. Copyright © Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology.]

3.2.2. Chitosan-based hybrid nanoparticles

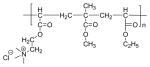

Due to the hydrophilic nature of chitosan, nanoparticles made of chitosan alone have limited encapsulation potential for hydrophobic drugs [115]. To further improve the drug entrapment, as well as specific targeting, controlled release and toxicity reduction capability of nanoparticles made of chitosan alone, a second polymer or oligomer such as sodium alginate, hyaluronic acid, cholesteryl 3-hemisuccinate, dextran sulfate, sulfobutyl ether-cyclodextrin, Carbopol®, or lecithin (Tables 3 and 4) has been added into the chitosan nanoparticles for ocular drug delivery applications [95, 99, 101, 103, 115–120]. These second polymers/oligomers have plenty of anionic carboxylic, sulfonate or phosphate groups which can form ionic interaction with cationic chitosan so that they can act as crosslinkers like tripolyphosphate which is commonly used for crosslinking chitosan. The crosslinking can increase the tightness of chitosan nanoparticles, and subsequently increase the ocular retention time of the loaded drugs and/or the ocular penetration of the chitosan nanoparticles, decrease the initial burst, and increase the ocular bioavailability of the drugs [95, 99]. Table 8 summarizes various drug-loaded chitosan-based hybrid nanoparticles and their characteristics.

Table 4.

Chemical structures of polysaccharides used for drug delivery to the anterior segment of the eye.

| Name | Chemical Structures |

|---|---|

| Chitosan |

|

| Chlolesterol modified chitason (CS-CH) |

|

| Hyaluronic acid (HA) |

|

| Sodium alginate |

|

| Sulfobutylether-cyclodextrin |

|

| Carboxymethyl tamarind kernel polysaccharide |

|

| Pectin |

|

| Dextran Sulfate |

|

| Gum Cordia | Natural anionic gum (Structure N/A) |

| Pullan |

|

Table 8.

Examples of drug-loaded chitosan-based hybrid nanoparticles.

| Primary Polymer | Other Compon ent |

Fabrication Method |

Drug Encapsula ted |

Size (nm) |

Zeta Potential (mV) |

Encapsula tion Efficiency (%) |

In vitro Release |

In Vivo Observations |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan–sodium alginate | pluronic ® F-127 | ionotropic gelation (modified coacervation method) | gatifloxacin | 205 to 572 | +17.6 to +47.8 mV | 77 to 82 | 90% in 24 h | na | [95] |

| Chitosan-sodium alginate | Tween® 80 | ionotropic gelation | betamethasone sodium phosphate | 16.8 to 692 | +18.49 to +29.83 | 64 | ~95% release in 24–72 h | showed sustained release pattern in vivo in vitreous humor (at least 24 h) and good permeability of drug compared to the solution formulations | [96] |

| Thiolated chitosan (TCS)-alginate (ALG) | - | ionotropic gelation | FITC | 265.7±7. 4 (CS-ALG) and 408.0±6. 4 (TCS-ALG) | +29.5±4. 1 (CS-ALG) +49.2±2. 3 (TCS-ALG) | 84.2±1.8 (CS-ALG) 92.1±1.9 (TCS-ALG) | - | - | [278] |

| Hyaluronic acid-chitosan | TPP | ionotropic gelation | gene (plasmid PEGFP or PB-gal) | 100 to 235 | −30 to + 28 | ~99.9 | - | provided high transfection levels (up to 15% of the cells);nanoparticles were internalized by fluid endocytosis, mediated by hyaluronic receptor CD44 | [97] |

| Hyaluronic acid modified chitosan (CS-HA) | TPP-for unmodified | ionotropic gelation | timolol maleate (TM) / dorzolamide hydrochloride (DH) | 143.9 ± 6.3 (chitosan) 319.5 ± 4.0 (CS-HA) | +34.1 ± 6.4 (chitosan) +33.3 ± 6.1 (CS-HA) | Chitosan: DH (91.0±2.9) and TM (54.2±1.0); CS-HA: DH( 85.1±2.3) and TM( 19.3±2.0) | ~100% in 24 h (Chitosan); ~20% in 24 h (CS-HA) | in terms of overall reduction of ΔIOP in vivo, CS-HA nanoparticles outperformed chitosan nanoparticles and marketed formulation | [279] |

| Cholesterol modified chitosan (CS-CH) | - | self-aggregation through sonication or diafiltration | CsA | 185.2 to 226.1 | +43.14 to + 44.88 | 41.8 | 60% in 4 h and 95% in 48 h | showed good retention ability at the procorneal area while no activity was detected in the posterior segment | [118] |

| Cholesterol modified chitosan (CS-CH)-PLA | - | nanoprecipitation | rapamycin | 312 to 326 | + 30.3 | 75.2 to 89.3 | ~25% in 4 h and ~85% in 8 days | chitosan-CH/PLA nanoparticles improved the immunosuppressive effect of rapamycin in corneal transplantation in rabbits as effectively as and even slightly better than rapamycin suspension in terms of the medial survival time of the corneal allografts (27.2 ± 1.03 days vs. 23.7 ± 3.20 days) | [253] |

| Chitosan/Carbopol | - | ionotropic gelation | pilocarpine | 294±30 | +55.78± 3.41 | 77±4 | ~30% in 2 h and 65% in 24 h | during in vivo miotic study, the nanoparticle formulation showed four fold higher AUC(0–24h) compared to drug solution in terms of decrease in pupil diameter | [98] |

| Chitosan/sulfobutylether-beta-cyclodextrin | - | ionotropic gelation | econazole nitrate | 90 to 673 | + 22 to 33 | 13.37 to 45.67 | ~50% in 8 h | nanoparticles provided greater antifungal effect to the eye surface than drug solution (rabbit) | [99] |

| Chitosan/sulfobutylether-beta-cyclodextrin | - | ionotropic gelation | naringenin | 446.4 ± 112.8 | +22.5 ± 4.91 | 67.10 ± 0.26%. | ~100% in 5 h | increased AUC(0-t) (4.6-fold) and Cmax (3.7-fold) of the drug compared to drug suspension | [280] |

| lecithin/chitosan | - | ionotropic gelation | natamycin | 213.83 ± 2.02 | 43.83±1. 80 | 73.57±0.62 | ~40% in 2 h and ~60% in 7 h | increased (~1.5 fold) AUC (0-inf) of natamycin in precorneal region compared to drug solution; total drug available above the MIC (AUC above MIC) by nanoparticles was ~1.53 fold higher than drug solution | [100] |

| Chitosan - alginate | - | ionotropic gelation | daptomycin | ~375 to 470 | −20 to +25 | ~60 to 99 | - | - | [89] |

| Lecithin-chitosan | - | ionotropic gelation | amphotericin B | 161.9 to 230.5 | +26.6 to +38.3 | 70 to 75 | ~80% in 10h | improved drug levels (~2.04 fold) and precorneal residence time (~3.36 fold) of nanoparticles compared to marketed formulation | [101] |

| chitosan or alginate nanoparticles | polaxamer 188; lecithin; PVA; HPMC; Methocel; TritonTM X-100 | spontaneous emulsification/solvent diffusion | celecoxib | 113.33± 4.08 (chitosan); 154.67± 5.06 (alginate) | +36.92± 3.38 (chitosan) - 36.5±4.7 (alginate) | 89.88±4.17 (chitosan); 75.38±2.98 (alginate) | after 24 h, drug release from CS-NPs & ALG NPs preparations eye drops, preformed gel and the in situ gelling system was (61.5, 50.1, 44.6%) and (51.3, 46.7 and 40.1%) respectively. | - | [102] |

| hyaluronic acid coated chitosan | TPP | ionotropic-gelation | dexamethasone | ~305 (before coating); 400 (after coating) | +32.55 (before coating); −33.74 (after coating) | 72.95 | ~30% in 1 h and ~65% in 12 h | chitosan nanoparticles and HA-coated chitosan nanoparticles showed 1.83-fold and 2.14-fold higher AUC(0–24 h) in rabbit aqueous humor, respectively compared to dexamethasone solution | [271, 273] |

Polyionic complex nanoparticles made of hybrid chitosan and sodium alginate could continuously release antibiotic gatifloxacin [95] and betamethasone sodium phosphate [96] for 24–72 h in vitro and generated smaller initial burst for gatifloxacin than the chitosan or alginate alone [95]. An ex vivo permeability study showed that chitosan-alginate nanoparticles could penetrate through the rabbit sclera. In vivo studies of these nanoparticles in rabbits showed sustained release of betamethasone sodium phosphate for 12–24 h depending on the formulations when compared with the drug solution alone which disappeared after 2 h [96]. Zhu et al. [121] synthesized thiolated chitosan and evaluated the potential of thiolated chitosan-sodium alginate nanoparticles for ocular delivery. Results from their in vitro cytotoxicity study showed that the thiolated chitosan-sodium alginate nanoparticles were not cytotoxic to human corneal epithelial cells (HCE). Compared with chitosan-sodium alginate nanoparticles, thiolated chitosan-sodium alginate nanoparticles were smaller, more stable and adhesive, showed greater intracellular uptake by HCE cells, and delivered more FITC (model drug) into corneas [121].

Alonso and associates investigated the effectiveness of hyaluronic acid (HA) modified chitosan (chitosan-HA) nanoparticles for delivering genes to the cornea and conjunctiva [97, 122]. The zeta potential values of the chitosan-HA nanoparticles varied from positive to negative with increasing HA content. The transfection results demonstrated that the chitosan-HA nanoparticles were able to render high transfection levels to immortalized human corneal epithelial and normal human conjunctival cells (up to 15% of cells transfected), without affecting cell viability. After topical instillation into rabbit eyes, the chitosan-HA nanoparticles were internalized into the conjunctiva more than the cornea. Confocal images revealed that the internalization of chitosan-HA nanoparticles was due to fluid endocytosis, and the process was mediated by hyaluronan receptor CD44 (Figure 7). The nanoparticles were evenly distributed in corneal epithelial cells, but unevenly in conjunctival cells with more intense localization in the apical and basolateral regions. Vyas and associates [103] evaluated the effectiveness of these chitosan-HA nanoparticles for delivering timolol maleate and dorzolamide hydrochloride to the eye for the management of glaucoma. As expected, the addition of HA in the nanoparticles showed increased ex vivo mucoadhesion and transcorneal permeation of the drug through excised goat cornea when compared with chitosan nanoparticles alone. Both chitosan-HA and chitosan nanoparticles showed in vitro burst release. Most of the loaded timolol maleate was released out of the chitosan/chitosan-HA nanoparticles as timolol was molecularly dispersed in the nanoparticles, whereas only 20% of the loaded dorzolamide hydrochloride was released due to its crystalline form. The timolol/dorzolamide hydrochloride loaded chitosan-HA nanoparticles did not cause any apparent ocular irritation to albino rabbits. They reduced intraocular pressure significantly more in the fellow eyes but less in the contralateral eyes of albino rabbits after 24 h of instillation [103]. The chitosan-HA nanoparticles caused higher intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering and less systemic absorption of the two drugs timolol and dorzolamide hydrochloride than the chitosan nanoparticles and the drug solutions after the instillation [103].

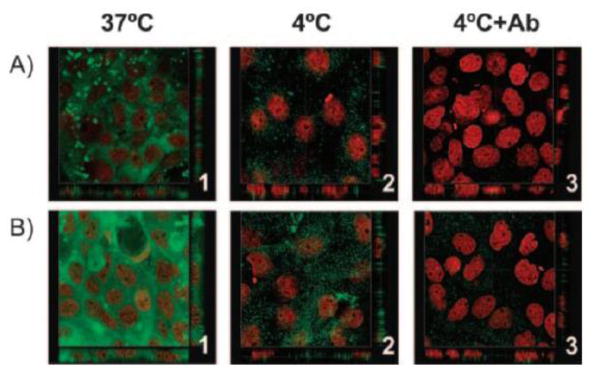

Fig. 7.

Confocal images showing the internalization of (A) Hyaluronic acid: Chitosan oligomer (mass ratio, 1:2), and (B) Hyaluronic acid: Chitosan (mass ratio, 2:1) NP in HCE cells. The NPs were incubated at 37°C (1), 4°C (2), and 4°C after blocking of the CD44 receptor with the monoclonal antibody Hermes-1 (3). The images show cross sections in the x–y and x–z axes of the series. HA was labeled with fluoresceinamine (green), and the cell nuclei were stained with propidium iodide (red). Magnification, 63. An extensive internalization of nanoparticles was observed at 37°C evidencing endocytic uptake of the nanoparticles into the cells (B1). The observed minor cell association at 4°C could be attributed to the receptor-mediated uptake of the particles (B2). However, when the study was repeated at 4°C in presence of CD44 receptor blocker (monoclonal antibody Hermes-1), a negligible uptake of nanoparticles was observed (B3), thus concluding the internationalization mechanism as CD44 receptor-mediated endocytosis. [Reprinted from de la Fuente, Maria, Begona Seijo, and Maria J. Alonso. “Novel hyaluronic acid-chitosan nanoparticles for ocular gene therapy.” Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 49.5 (2008): 2016–2024. Copyright © Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology]

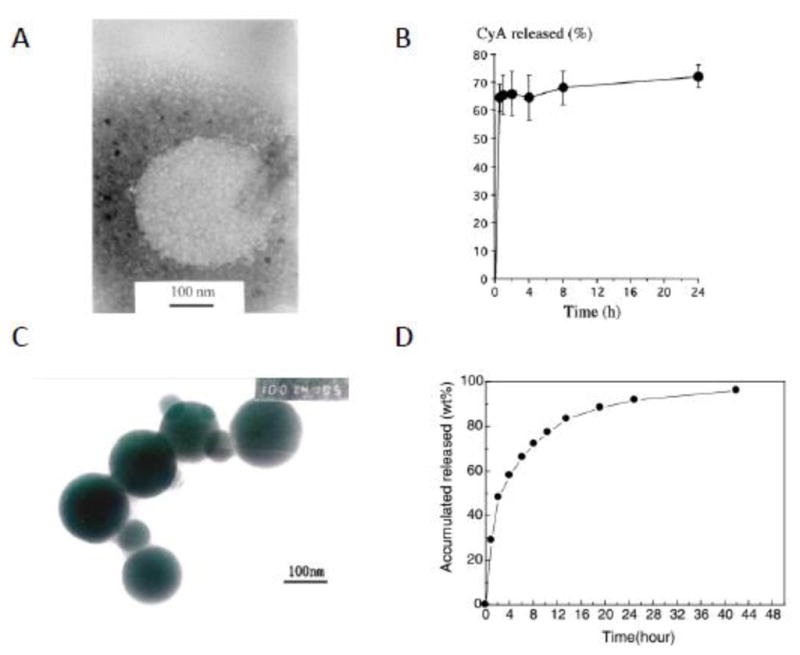

Yuan X et al. [118] synthesized amphiphilic conjugates of hydrophilic chitosan and hydrophobic cholesterol (CH) and obtained CH modified chitosan (chitosan-CH) nanoparticles through self-aggregation, and evaluated their potential for drug delivery to the ocular surface. The formed nanoparticles had an average particle size of about 200 nm and an average zeta potential of about 44 mV. They showed good dispersion over the entire precorneal area of rabbits following topical administration. While some of the chitosan-CH nanoparticle suspension was observed to be drained into lacrimal sac through the lacrimal duct, 71.4% of the chitosan-CH nanoparticles were well retained at the precorneal area at 112 min post-administration due to the bioadhesion ability of chitosan. Subsequently, the chitosan-CH nanoparticles retained at the cornea and conjunctiva, but would hardly permeate into the iris/ciliary body and reach to the posterior segment of the eye due to the tight barrier of the cornea. Hydrophobic drug CsA was entrapped in these nanoparticles using a simple dialysis method. In comparison with the chitosan nanoparticles alone, chitosan-CH nanoparticles enhanced both the CsA loading content and loading efficiency of chitosan nanoparticles (9% and 73%, vs. 6.2% and 41.8%, respectively). The chitosan-CH nanoparticles showed sustained release of CsA for over 48 h compared with the chitosan nanoparticles (24 h), and less initial burst than the chitosan nanoparticles alone (60% released in 4 h vs. 62% released in 15 min) as shown in Figure 8 [118, 123]. The reason for the less initial burst was probably due to the hydrophobic nature of the cholesterol component. This group also showed that further incorporation of hydrophobic poly(lactic acid) into the chitosan-CH nanoparticles could significantly improve the loading efficiency of rapamycin by ~4 fold and slow rapamycin release by reducing the percentage of rapamycin released at 12 h from 85% to 50% [124]. Furthermore, the chitosan-CH/PLA nanoparticles improved the immunosuppressive effect of rapamycin in corneal transplantation in New Zealand rabbits as effectively as and even slightly better than rapamycin suspension in terms of the medial survival time of the corneal allografts (27.2 ± 1.03 vs. 23.7 ± 3.20 days).

Fig. 8.

Transmission electron micrograph of the CsA-loaded CS nanoparticles (prepared by ionotropic gelation method) (A). In vitro CsA release profile from CyA-loaded CS nanoparticles (B) [Reprinted from International journal of pharmaceutics, 224(1), (2001). De Campos, A. M., Sánchez, A., & Alonso, M. J. Chitosan nanoparticles: a new vehicle for the improvement of the delivery of drugs to the ocular surface. Application to cyclosporine A. 159–168. Copyright © 2001 Elsevier Science B.V., with permission from Elsevier]. TEM micrographs of cholesterol modified chitosan nanoparticles (formed by self-aggregation) (C). In vitro CsA release from CS-CH self-aggregated nanoparticles (D) [Reprinted from Carbohydrate Polymers 65.3 (2006). Yuan, X. B., Li, H., & Yuan, Y. B. Preparation of cholesterol-modified chitosan self-aggregated nanoparticles for delivery of drugs to ocular surface. 337–345 Copyright © 2006 Elsevier Ltd, with permission from Elsevier.]

Hybrid nanoparticles made of chitosan and Carbopol® with 294 nm particle size were used to load pilocarpine [98]. The subsequent in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that these hybrid nanoparticles could slowly release pilocarpine for 24 h to decrease the pupil diameter of rabbits (miosis effect) more effectively than pilocarpine in liposome, gel and eye drop formulations. Hybrid nanoparticles made of chitosan and dextran sulfate with around 400 nm particle size and around 40 mV zeta potential were stable in the presence of lysozyme for at least 4 h and showed at least 60 min prolonged adherence to the ex vivo porcine corneal surface [117]. After topical instillation of mucoadhesive chitosan-dextran sulfate nanoparticles (~400 nm size/+48 mV zeta potential; FITC labelled), the nanoparticles showed prolonged retention on porcine ocular surface for more than 4 h, and could be endocytosed into the ex vivo porcine corneal epithelial cells via clathrin-dependent pathway (Figure 9) [125]. Furthermore, after 6 h of topical administration, theses chitosan-dextran sulfate nanoparticles were observed to not be able to penetrate through corneal epithelium into stroma (Figure 10) [125]. Beta-cyclodextrin and its derivatives have a unique property of forming inclusion complexes with hydrophobic drugs to increase these drugs’ water solubility due to their hydrophobic central cavity made of seven glucose units [126, 127]. In ocular application, sulfobutyl ether β-cyclodextrin was used to make hybrid nanoparticles with chitosan to form inclusion complexes with econazole nitrate to increase the water solubility of econazole nitrate. The resulting econazole nitrate-containing complexes showed improved bioavailability and prolonged 8 hours’ steady antifungal effect while econazole nitrate solution could provide an antifungal effect for only 3 hours which also dramatically decreased with time [99].

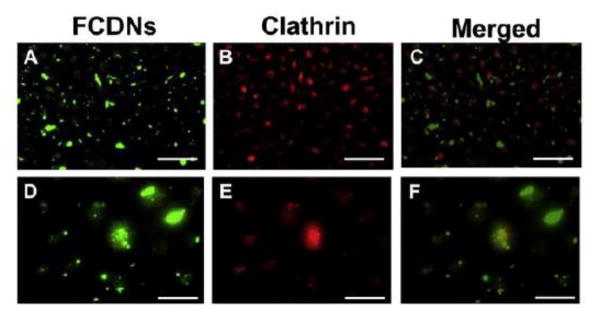

Fig. 9.

Uptake of FITC labeled Chitosan-Dextran sulfate Nanoparticles (FCDNs) occurs by a clathrin-dependent mechanism. (A, D) Images taken incubation with of cells FCDNs for 30 min at 37 C. (B, E) Cells are stained with clathrin (red). (C, F) Merged image showing the colocalization of FCDNs and clathrin (i.e., yellow spots). Magnification: (A–C) ×20; (D–F) ×63. Scale bar: (A–C) = 50 μm; (D–F) = 20 μm. Images shown are typical results after 3 independent trials. [Reprinted from Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 149 (2017). Chaiyasan, W., Praputbut, S., Kompella, U. B., Srinivas, S. P., & Tiyaboonchai, W. Penetration of mucoadhesive chitosan-dextran sulfate nanoparticles into the porcine cornea. 288–296. © 2016 Elsevier B.V. with permission from Elsevier.]

Fig. 10.

Cross section of the porcine cornea after its exposure to FCDNs for 3 h. (A) Intact corneal epithelium. (B) After removal of the corneal epithelium. Scale bar = 250 μm. Images shown are typical results after 3 independent trials. [Reprinted from Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 149 (2017). Chaiyasan, W., Praputbut, S., Kompella, U. B., Srinivas, S. P., & Tiyaboonchai, W. Penetration of mucoadhesive chitosan-dextran sulfate nanoparticles into the porcine cornea. 288–296. © 2016 Elsevier B.V. with permission from Elsevier.]

Hybrid nanoparticles made of chitosan and lecithin had a particle size of ~100 nm and zeta potential value of around 27 to 43 mV, and were used for controlled release of natamycin [100], amphotericin B [101], and celecoxib [102]. In vitro release of natamycin showed a biphasic release profile with an initial burst release ~41.23% in 2 h followed by a slow release ~64.22% in 7 h [100]. However, in vitro release of celecoxib showed 24 h sustained release without initial burst [102]. In vivo ocular pharmacokinetics study of natamycin in New Zealand rabbits showed that the hybrid chitosan-lecithin nanoparticles increased the AUC(0-∞) of natamycin 1.47-fold and decreased the clearance of natamycin 7.4-fold compared with the marketed natamycin suspension [100, 101]. In vivo ocular pharmacokinetics study of amphotericin B in albino rabbits showed that the hybrid chitosan-lecithin nanoparticles significantly improved the bioavailability (~2.04-fold) and precorneal residence time (~3.36-fold) of amphotericin B compared with amphotericin B solution (Fungizone®) available in the market [101].

3.2.3. Nanoparticles made of other polysaccharides

Other polysaccharides such as pectin, gum cordia, carboxymethyl tamarind kernel polysaccharide, galactomannan polysaccharide, and hyaluronic acid have also been used to make nanoparticles for ocular drug delivery [104–107, 128]. In an ex vivo study, pectin nanoparticles were found to significantly increase the permeability of timolol maleate across the excised goat cornea 200% more than the conventional timolol maleate ophthalmic solution [104]. On the other hand, gum cordia and carboxymethyl tamarind kernel polysaccharide nanoparticles were found to not enhance the permeation of loaded drugs fluconazole and tropicamide across the goat cornea as compared with the respective drug ophthalmic solutions [105, 107]. The authors speculated that even though these two types of nanoparticles did not increase the drug ex vivo corneal permeability, they might be able to provide sustained drug delivery in vivo due to their prolonged residence time in the cul-de-sac. Horvat et al. demonstrated that the gel formulations made of nanosized crosslinked sodium hyaluronate, prepared by crosslinking via the carboxyl groups of the HA chains with a diamine using a carbodiimide technique, exhibited the highest capability of mucoadhesion compared with the gels made of linear HA derivatives (linear sodium hyaluronate, zinc hyaluronate). The explanations were that the interchain crosslinking structure and nanosize dimensions might enable the crosslinked sodium hyaluronate to interpenetrate easily and form secondary bonds with the mucin. Despite their differences in chemical and physical structures, all the above three types of nanoparticles showed an initial burst release of model drug sodium diclofenac at ~35–55% in 1 h, and released up to ~60–88% at 6 h [106]. Table 9 summarizes various drug-loaded nanoparticles made of other polysaccharides and their characteristics.

Table 9.

Examples of drug-loaded polysaccharide-based nanoparticles (other than chitosan).

| Primary Polymer |

Other Component |

Fabrication Method |

Drug Encapsulated |

Size (nm) |

Zeta Potential (mV) |

Encapsulation Efficiency (%) |

In Vitro Release |

In Vivo |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiolated pectin | magnesium chloride | ionotropic-gelation | timolol maleate | 237 | - | 94.6 | - | - | [104] |

| Sodium hyaluronate; Zinc hyaluronate | - | carbodiimide technique for crosslinked structures | sodium diclofenac | <110 | - | 100 | showed an initial burst release of model drug sodium diclofenac at ~35–55% in 1 h, and released up to ~60–88% at 6 h | - | [106] |

| Gum cordia | polyvinyl alcohol/calcium chloride | emulsion cross-linking technique | fluconazole | 315 to 394 | −55 to −48 | 65 to 93 | - | - | [105] |

| Tamarind seed xyloglucan nanoaggregates | poloxamer-407 | nanoaggregation | tropicamide | 639.8 | - | 96.57 | - | - | [258] |

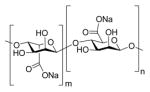

3.3. Polyester nanoparticles

Polyesters such as poly(lactide) (PLA), poly(lactide-co-glycoside) (PLGA) and poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) (Table 2) are synthetic polymers which are biodegradable with good biocompatibility. These polymers have been extensively used to fabricate implants, microparticles, and nanoparticles for controlled drug release and targeted drug delivery. In particular, nanoparticles fabricated from PLA, PLGA and PCL have been evaluated for drug delivery to the eye [129–135]. Drug or non-drug-loaded PLA, PLGA and PCL nanoparticles have been fabricated using solvent displacement (i.e. nanoprecipitation) [132–134, 136–138], and oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion solvent evaporation techniques [135, 139]. The resulting nanoparticles have particle sizes in the range of a hundred to a couple of hundred nanometers and bear negative zeta potentials. Hydrophobic drugs such as sparfloxacin, indomethacin, cyclosporine A, natamycin and flurbiprofen and hydrophilic drugs such as brimonidine and diclofenac sodium were encapsulated in these polyester nanoparticles. Below are detailed discussions about how PLA, PLGA and PCL and their derivative nanoparticles have been investigated to mask drug irritation to the eye, improve drug loading in the formulations, increase drug retention time in the precorneal area, and/or enhance drug penetration into/across the cornea or the conjunctiva-sclera barrier to reach the inner anterior segment [130, 132, 134, 137, 139–142].

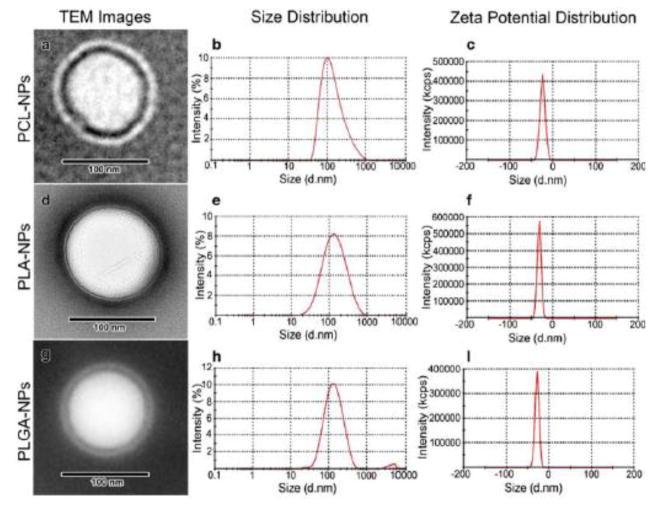

Self-assembled polymeric micelles were synthesized from amphiphilic copolymers bearing a hydrophobic poly(2-methyl-2-carboxytrimethylene carbonate-co-D,L-lactide) backbone and a hydrophilic poly(ethylene glycol)-azide pendant chain [143]. GRGDS peptide was conjugated to the self-assembled micelles to target corneal epithelial cells through RGD receptors. In vitro evaluation of the binding affinity of these GRGDS-modified micelles to rabbit corneal epithelial cells showed that GRGDS-modified micelles could significantly inhibit the attachment of corneal epithelial cells to GRGDS-coated plates, indicating these micelles could be used for targeted drug delivery to the injured eye. PLGA nanoparticles prepared by nanoprecipitation were tested for ex vivo permeability across the cornea of New Zealand rabbits by Vega et al. [134]. The results showed that the PLGA nanoparticles considerably increased the penetration of flurbiprofen across the cornea by 4-fold over free flurbiprofen PBS (pH 7.4) solution and by about 2-fold over the commercial Ocuflur™ eye drops [134]. Corneal hydration study indicated that the corneas were not damaged during the 6 h ex vivo corneal permeability study. Similar drug penetration enhancement was observed on ex vivo goat corneas for sparfloxacin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles [137]. Further, in vivo ocular retention study on New Zealand rabbits using scintigraphy studies revealed that radiolabeled sparfloxacin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles were cleared at a much slower rate and retained for a much longer duration at the corneal surface than commercial sparfloxacin eye drops. This was evidenced by the facts that after topical instillation radioactivity was detected in the systemic circulation (kidney and bladder) at 6 h with radiolabeled sparfloxacin eye drops but not with radiolabeled sparfloxacin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles; and radioactive counts at corneal surface within the first 0.5 h quickly decreased with radiolabeled sparfloxacin eye drops but remained nearly constant with radiolabeled sparfloxacin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles [137]. Since PLGA nanoparticles are hydrophobic and negatively charged at the surface, they are non-mucoadhesive in nature [137]. Therefore, the observed long retention for the nanoparticles would probably due to the particle size of the nanoparticles (180–190 nm) [137, 144]. In addition to the PLGA nanoparticle size effect, the poly(vinyl alcohol) stabilizer was also found to help to increase the nanoparticle retention time by increasing the viscosity of the nanoparticle dispersion due to the hydrophilic nature of the poly(vinyl alcohol) polymer [137, 140]. Diclofenac sodium-loaded PLGA and poly (lactide-co-glycolide-leucine) polymeric nanoparticle suspensions with size ~125–190 nm, and zeta potential ~-25 mV showed a biphasic release pattern of the drug: one initial fast release (~50% in first 2 h) followed by a second slow-release phase for up to 14 h, and the particles were observed to be free of any irritant effect on cornea, iris, and conjunctiva for 24 h after topical application in rabbit eyes [142]. PCL nanocapsules have been studied for topical ocular drug delivery by Alonso and co-workers [136, 140, 145]. These PCL nanocapsules were made from PCL, lecithin and Miglitol 840 using solvent displacement technique. The fluorescent dye loaded PCL nanocapsules with a mean size of 252 nm have enhanced the penetration of rhodamine 6G through the corneal epithelial cells of New Zealand rabbits by endocytosis ex vivo, and were selectively internalized into the corneal epithelium cells (vs. the conjunctival cells) after topical instillation to the cul-de-sac of fully awake New Zealand rabbits [140]. PCL nanocapsules loaded with indomethacin had an average particle size of 238 nm and a zeta potential of −39 mV and were well tolerated by New Zealand rabbits, and significantly increased the indomethacin concentrations in the cornea (~3.2-fold increase in AUC) and aqueous humor (~4.3-fold increase in AUC) than commercial eye drop Indocollyre after topical instillation to the cul-de-sac of the right eyes in New Zealand rabbits [136]. After PCL nanoparticles had been functionalized with poly-D-glucosamine, the obtained nanoparticles prolonged the release of natamycin for up to 8 h in vitro, and significantly increased relative bioavailability (~6.03–6.39-fold) compared to the commercial natamycin suspension (Natamet®) [138]. Ibrahim et al. loaded brimonidine into PLA (molecular weight 152 kDa), PLGA 75:25 (molecular weight 66–107 kDa) and PCL (molecular weight 14 kDa) nanoparticles which had 117~131 nm mean particle size, −18~ −28.11 mV zeta potential (Figure 11) [135]. The nanoparticles could encapsulate 68–78% of brimonidine, and the encapsulation efficiency increased in the order of PLGA<PLA<PCL with increasing the hydrophobicity of the polymers and the consequent solid-state solubility of the hydrophobic brimonidine freebase in the polymers. The in vitro release rates of brimonidine from the nanoparticles increased in the order of PCL>PLGA>PLA due to the decrease of the molecular weights of the polymers used in the nanoparticle preparations. Ibrahim et al. further embedded the brimonidine-loaded nanoparticles into methyl cellulose-based gels and demonstrated that the resulting brimonidine-nanoparticle-gel systems had significant better IOP lowering effect than brimonidine-containing Alphagan P® eye drops (effective duration 15.2–23.2 vs. 7–7.4 h) after instillation in BXD (boxed molecular dynamics) mice [135].

Fig. 11.

TEM images, size and zeta potential distribution curves for brimonidine-loaded nanoparticles. TEM image (a), size distribution curve (b) and zeta potential distribution curve (c) of PCL-nanoparticles, TEM image (d), size distribution curve (e) and zeta potential distribution curve (f) of PLA-nanoparticles, TEM image (g), size distribution curve (h) and zeta potential distribution curve (i) of PLGA-nanoparticles. [Reprinted permission “Pharmaceutical research. Novel topical ophthalmic formulations for management of glaucoma. 30.11 (2013): 2818–2831. Ibrahim, M. M., Abd-Elgawad, A. E. H., Soliman, O. A., & Jablonski, M. M. © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013.” With permission of Springer]