Abstract

Background

The TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly; Guidance, Education, Tools) Antibiotics Toolkit aims to improve antimicrobial prescribing in primary care through guidance, interactive workshops with action planning, patient facing educational and audit materials.

Objective

To explore GPs’, nurses’ and other stakeholders’ views of TARGET.

Design

Mixed methods.

Method

In 2014, 40 UK GP staff and 13 stakeholders participated in interviews or focus groups. We analysed data using a thematic framework and normalization process theory (NPT).

Results

Two hundred and sixty-nine workshop participants completed evaluation forms, and 40 GP staff, 4 trainers and 9 relevant stakeholders participated in interviews (29) or focus groups (24). GP staffs were aware of the issues around antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and how it related to their prescribing. Most participants stated that TARGET as a whole was useful. Participants suggested the workshop needed less background on AMR, be centred around clinical cases and allow more action planning time. Participants particularly valued comparison of their practice antibiotic prescribing with others and the TARGET Treating Your Infection leaflet. The leaflet needed greater accessibility via GP computer systems. Due to time, cost, accessibility and competing priorities, many GP staff had not fully utilized all resources, especially the audit and educational materials.

Conclusions

We found evidence that the workshop is likely to be more acceptable and engaging if based around clinical scenarios, with less on AMR and more time on action planning. Greater promotion of TARGET, through Clinical Commissioning Group’s (CCG’s) and professional bodies, may improve uptake. Patient facing resources should be made accessible through computer shortcuts built into general practice software.

Keywords: Antibiotics, common illnesses, health promotion, lifestyle modification/health behaviour change, primary care, public health

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Department of Health (DH) action plans on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) (1,2) stress the importance of improving professional education and public engagement to improve antimicrobial prescribing practice. In response, Public Health England with the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) and other professional societies have developed the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools) for primary care in England. TARGET is hosted on the RCGP website (http://www.rcgp.org.uk/targetantibiotics). TARGET aims to help prescribers and commissioning organizations to increase responsible antimicrobial prescribing in the primary care setting (3,4). There are seven key resource areas that make up the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit; an interactive workshop presentation, patient leaflets (Treating Your Infection), audit toolkits, National antibiotic management guidance, training resources, resources for clinical and waiting areas and a self-assessment checklist

This study aimed to explore perceptions of the value of the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit and investigate attitudes, perceptions and opinions about, and use of, the materials using the Normalization Process Theory (NPT) (5). The NPT is a framework made up of four constructs that allow us to examine and understand the dynamics of implementing, embedding and integrating new interventions.

Methods

We used a mixed methods approach to explore perceptions, attitudes and opinions. TARGET workshops given by 10 trainers involved 56 GP practices with 318 primary care staff (including receptionists, practice managers and other non-prescribing staff) were conducted across England as part of a wider evaluation (6) where all practice staffs were invited to take part in the workshop to encourage a whole practice approach to antimicrobial stewardship (AMS). Trained staff delivered the 1 h workshop covering AMR, guidance, how to optimize antibiotic prescribing, use of resources in the Toolkit, reflection on their own antibiotic prescribing data and some action planning. Workshop participants completed a five-point Likert scale evaluation form immediately after each workshop to assess its effectiveness.

Focus group and interview participants

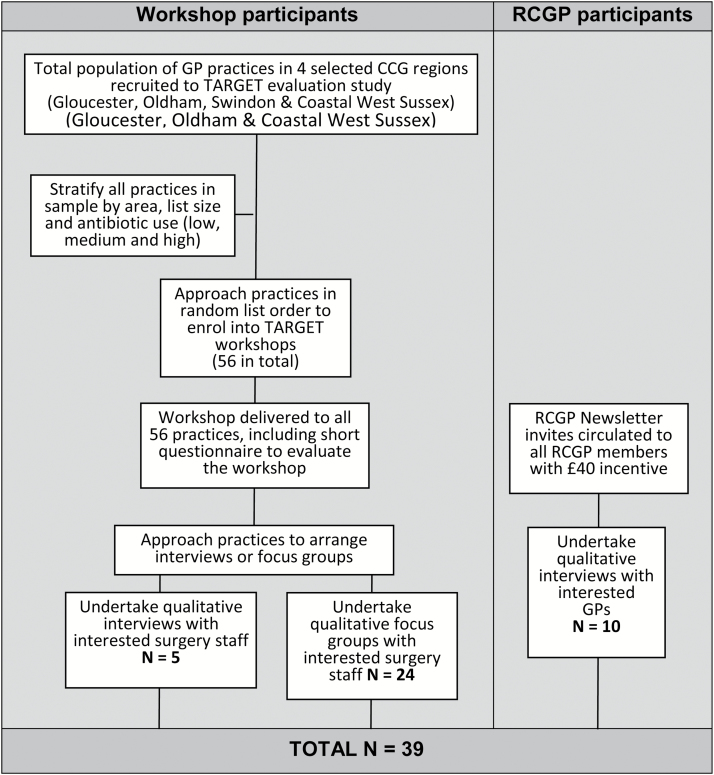

We sought participants with a wide range of familiarity with the resources to minimize positively biased opinions. We invited trainers who had delivered TARGET workshops, GP and other staff who had participated in workshops in the previous 6–14 months who had and had not used TARGET materials and members of the RCGP via newsletters, to participate in focus groups or interviews (Fig. 1). Where multiple people who had had a workshop from a practice agreed to take part, we conducted a focus group. Two newsletters from the RCGP invited participants, the second recruitment advert (Supplementary Material) specifically highlighted our requirement to speak to not only those that use TARGET but also to those that have decided not to use TARGET. We also communicated with the Royal Pharmaceutical Society to recruit relevant stakeholders for interview.

Figure 1.

GP staff recruitment flow chart (2014–2015).

Interview schedule

The schedule, developed by the study group of GPs, psychologist, microbiologist and medicine managers, explored participants’ opinions about the TARGET Toolkit, the TARGET workshop if attended, ongoing use of TARGET and the website and perceived usefulness of each of the resources (which were shown to participants or they were guided through the website if being interviewed over the telephone) and suggested improvements. The schedule also explored social norms around antimicrobial use and AMS by asking about colleagues’ and Clinical Commissioning Groups’ (CCGs’) attitudes and how they and others were or thought they should be implementing the materials, using computer prompts and audits or promoting AMS in their practice or area. The schedule was piloted with three GPs, and as no changes were made, these pilot results were included in the analysis. The schedule remained flexible throughout data collection allowing emerging themes to be incorporated.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face or by telephone, and focus groups were conducted in person; both lasted between 30 and 90 min. Field notes of the most important themes arising were made immediately after the interview or focus group. Interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Analysis

Transcripts were read and checked for accuracy and to gain familiarity with the data. Initial themes were coded by one researcher (LJ) using the computer software QSR NVivo 10 with a thematic analysis framework. A second researcher (RO) coded 20% of the transcripts to check for coding consistency. No disagreements arose in the coding discussions; consensus was reached on the coding framework by both coders. These researchers were not involved in workshop or resource development, but both now promote TARGET resources.

The themes identified during the analysis were placed within the NPT framework (5). The NPT was chosen for the purpose of understanding implementation (or not) of the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit. The framework breaks down the implementation process and provides an in-depth analysis of each of the action stages involved with implementing an intervention. Through applying our data to the NPT, we can identify reasons why implementation did or did not occur, further informing intervention development. There are four fundamental constructs to the NPT that influence implementation of an intervention into routine practice:

(i) Coherence: the degree of understanding an individual has over the purpose and necessity of an intervention;

(ii) Cognitive participation: the degree of engagement towards implementing the intervention;

(iii) Collective action: the effort invested in completing the intervention and

(iv) Reflexive monitoring: the informal and formal evaluations individuals and group make about the intervention’s value.

The NPT allowed us to interpret the intervention implementation by identifying barriers and facilitators and helped inform modifications to its content and delivery.

Results

Workshop evaluation forms

Evaluation forms were returned by 269 of 318 (85%) workshop participants (166 GPs, 51 nurses, 15 other staff, 37 unknown as the questions were unanswered). Eighty percent (217/269) responded that the workshop helped them to understand how they could optimize their antimicrobial prescribing, and 88% (237/269) responded that the workshop helped them to understand why responsible antimicrobial prescribing was an important issue. Table 1 illustrates which of the TARGET resources participants found useful, would use personally and would use in their surgery.

Table 1.

TARGET resources evaluation section of the workshop evaluation form—projected future use and perceived usefulness: 269 returned (2014–2015)

| Would you use the resources personally? | Would you use the resources in your surgery? | Was the resource useful? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic guidance | 166 (62%) | 141 (52%) | 188 (70%) |

| Learning modules | 141 (52%) | 88 (33%) | 150 (56%) |

| Computer prompts | 89 (33%) | 88 (33%) | 118 (44%) |

| Information on delayed prescribing | 157 (58%) | 140 (52%) | 178 (66%) |

| Audits | 115 (43%) | 113 (42%) | 161 (60%) |

| Treating your infection leaflet | 170 (63%) | 162 (60%) | 194 (72%) |

| Posters | 108 (40%) | 170 (63%) | 172 (64%) |

| Self-assessment checklist | 92 (34%) | 81 (30%) | 151 (56%) |

In total, 53 professionals took part in the qualitative interviews and focus groups. Forty GP staff (35 GPs, 5 nurses) from England and Scotland participated in interviews (16) or focus groups (24); Of these 40 GP staff participants, 28% had attended a TARGET workshop and were using at least one resource, a further 28% had attended a TARGET workshop but weren’t using any of the resources. Forty percent had not attended a TARGET workshop but were using at least one TARGET resource, and 5% hadn’t attended a TARGET workshop and weren’t using any of the TARGET resources. We interviewed four workshop trainers from four CCGs involved in the workshop evaluation (two consultant microbiologists, one CCG antibiotics lead, one CCG administrator) and nine other relevant stakeholders involved in AMS from Scotland (3) and England (6) (three prescribing advisors, one clinical pharmacist, one pharmaceutical advisor, one public health strategist, one antimicrobial pharmacist, one primary care development lead and one antimicrobial prescribing project lead).

Coherence: The degree of understanding an individual has over the purpose and necessity of the TARGET intervention

The threat of AMR was well understood by participants. Several participants supported the need to tackle AMR and believed that something more needed to be done to address it. Many also believed that awareness needed to reach beyond GPs to other health care professionals and the general public. Those with somewhat indifferent views towards AMR were the ones who reported many of the barriers indicated in this study.

A few GPs were concerned that reducing antimicrobial prescribing would lead to an increase in hospital admissions; therefore, some GPs indicated they adopted a cautious approach to prescribing antimicrobials, prescribing even when guidance suggested otherwise.

Cognitive participation: The reported investment and engagement towards implementation of TARGET

All stakeholders were positive about TARGET and were promoting its use within their CCG or region. Around half of GPs reported using the TARGET resources to varying degrees, and a further third of participants said they were considering or intending to use or promote TARGET.

A small number of GPs and other stakeholders reported the Treating Your Infection Leaflet would reduce patient re-consultations and workload by educating patients; others reported it would ensure consistency in the messages given by GPs. Many participants said that they would use or promote the TARGET audits with several others stating they have already used them. Many had used other antimicrobial audit materials. The Public Health England antibiotic primary care guidance was considered very useful for most GPs, and many stated they valued the hard copies of guidance provided locally for easy access. The foremost barrier to intention to implement TARGET resources was lack of awareness of the website; thus, some indicated it needed wider promotion and others that it needed easier access.

Most GP staff and stakeholders described the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit as a useful resource, which addressed their own prescribing behaviour and patient expectations. They felt that it complemented existing efforts and was relevant to all practice staff in developing a consistent approach to patient enquiries about antimicrobials.

The majority of workshop participants felt the workshop was useful and thought the case scenarios and practice prescribing data were valuable and encouraged good debate around their own and other staff’s prescribing habits; some suggested more clinical scenarios. The introductory part covering AMR was criticized by some as repeating well-known information. One of the workshop trainers suggested that to facilitate more implementation of resources, practice staff would have benefited from more time at the end of the workshop to create a concrete action plan so that staffs were clearer about the exact follow-up actions required (see Table 2 for coherence and cognitive participation quotes).

Table 2.

Coherence and cognitive participation quotations (2014–2015)

| Coherence |

|---|

| the general message of using fewer antibiotics is what we have been trying to do for many years and continue to do so.—GP M1 |

| I think the reason why I have some traction is because we know in our heart of hearts it’s right. Right in that for the long term benefit, it’s also right in terms of a lot of these patients… the message is coming out to us as clinicians through like I say our professional body, RCGP, our academic journals, … general practice and material that gets sent out professionally like TARGET and CCG producing. You can’t ignore it because it’s, so I think that’s one of the, that helps.—GP M7 |

| Yes, because that five year antimicrobial strategy everyone is talking about it, we have talked enough but now is the time for action.—Stakeholder 4 |

| I guess it’s just trying to hammer home the message, isn’t it, and that sort of thing. It’s all very well me knowing, it’s patients knowing that’s the bigger issue,—GP C1 |

| Of course I’d consider it (AMS) but it’s just time in the day, it’s, personally I just feel like I’m maxed out, five day a week on the path to early burnout, like lots of GPs do.—GP C2 |

| it’s based on the feedback that some of the GPs were giving at the workshops, it’s the expectation of patients there and if they can’t get antibiotics from the GP then they may go to a walk in centre or even A&E to try and get what they need, you see?—Stakeholder 2 |

| I do out of hours still and we have a very low incidence of prescribing antibiotics, very low and I see them at out of hours, coming in with discharging ears.—GP C1 |

| [t]here’s a big push on reducing antibiotic prescriptions but also we’re all cautious of missing infections that potentially do need protecting and the consequences of that.—GP M2 |

| Cognitive participation |

|---|

| So do you intend to use the target materials in the future? —Yes, because it’s engrained into my practice now.—GP M3 |

| I like it because you get consistency of message and it, instead of everyone reinventing their own wheel patients will get a consistent message wherever they go—Stakeholder 7 |

| I think the leaflets are quite straightforward. If anything they’d make a consultation a lot easier and also reduce the chance of a re-consultation with another doctor.—Stakeholder 12 |

| And that kind of case discussion with the actual problems that we face is a better way of shifting behaviour,—GP M1 |

| surgeries needed to develop a plan for what they were going to do to reduce antibiotic prescribing within themselves… If you’re actually going to get the practice to do something there was no way that there was enough time in the one hour allocated to do that.—Stakeholder 5 |

| I felt it was very good to see how we compared to local other practices, that that was useful.—GP C1 |

| I thought it was interesting that I wasn’t aware of the Target programme but I was very much aware of all the Target information.—GP M7 |

Collective action: The effort invested in using TARGET

Some of the GPs and most of the other stakeholders had already started promoting AMS within their practice or CCG, through educational events, promoting TARGET, CCG incentives and using locally developed resources such as electronic prescribing dashboards, and practice leaflets and posters. Participants described several different local adaptations of the TARGET Treating Your Infection leaflet: A5 tear-off pads, pharmacy versions and trifold versions. Some participants suggested that a computer prompt, translation into other local languages and a simplified version may facilitate increased leaflet use. Although no participants had used the TARGET patient videos, a few suggested they would be useful to show on their waiting room screens.

Many participants stated they would or were planning to use the TARGET audits in future, and many had already used similar audits in the past. Very few individuals had used the RCGP TARGET online clinical courses; many were not aware of them. A few expressed an interest in using the courses for professional development. One participant said the online courses were too time consuming, whereas another said they would be fun to do at home or as a group practice effort.

For many participants, time, workload and competing priorities of other initiatives were the main barriers to implementing TARGET resources. There was also lack of clarity around whose responsibility it was to take forward actions discussed in the workshop, e.g. displaying posters. One stakeholder indicated that although individuals in practices may feel AMR is a priority, practices have other more pressing priorities. Several participants were concerned by the high cost of printing resources obtained from the TARGET website.

Reflexive monitoring: The informal and formal evaluations that individuals and groups make about the intervention’s value

Many participants admitted to not monitoring the effects of implementing TARGET and were therefore uncertain of its value, e.g. although posters were seen as useful for educating patients, some were unsure whether they had been displayed in their practice. Some felt they could be doing more to monitor the outcomes; one participant thought it was Public Health England’s responsibility to monitor any outcomes.

The TARGET audits could be used to evaluate practice prescribing; however, participants did not recognize the potential for using audits to monitor the effectiveness of the TARGET resources on their own practice. Several participants felt that antibiotic audits were valuable and had positive effects on practice, and two participants reported an antibiotic audit had directly impacted on their practice antimicrobial prescribing. A few participants did not see benefits from auditing, and several thought inadequate Read coding made audits unreliable.

Monitoring methods included stakeholders providing quarterly antibiotic prescribing data to practices, carrying out their own evaluations, anecdotal feedback and audits; none had done a formal evaluation. Several stakeholders felt it was too early to tell whether there had been any positive effects as they had only just implemented roll out of TARGET.

The self-assessment checklist is a key resource that can be used for monitoring but was infrequently mentioned by participants. A stakeholder mentioned using the checklist as a monitoring tool, asking GPs to complete it before and after implementing the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit; they reported that GPs found this very useful. Overall, an informed understanding of the overall benefits of TARGET was not held by any of the participants (see Table 3 for collective action and reflexive monitoring quotations).

Table 3.

Collective action and reflexive monitoring quotations (2014–2015)

| Collective action |

|---|

| Well I think it, information coming out from the CCG, we’ve put it on the CCG website and things like that so that more GPs are aware of it, because I would say it’s probably true that most GPs were not aware of the TARGET website.—Stakeholder 5 |

| [e]verything comes off the computer doesn’t it? You’re in the consultation and that’s what you hit the button for, the patient doesn’t need antibiotics and you explain why and out it comes, I would have thought that would be useful.—GP M11 (The Treating Your Infection leaflet) And similarly, and additionally the languages that are on offer don’t necessarily reflect all the languages we need.—Stakeholder 3 (The Treating Your Infection leaflet) |

| [w]e would probably have a relatively high illiteracy rate in some parts of (region) because of deprivation etc, it (The Treating Your Infection leaflet) might not be as easily understandable by some of our population,—Stakeholder 10 |

| It is now I think audit quality improvement, the trainees are required to do them in each post. It’s kind of a bit more, it’s embedded.—GP M7 (audits) |

| It was quite time consuming. And I’m not sure how likely GPs would be to spend that much time doing it—Stakeholder 7 (learning modules) |

| Yes, I think that would be quite fun, because you could do that at home in the evening, of course.—GP M11 (learning modules) |

| Probably because there’s not one person that’s responsible for them but there again that might be considered,—GP M2 (posters) |

| M But I think we, I think as a practice we’re probably quite good, so I don’t think it’s a, I think there are other things that are… |

| M More important.—FG G1 |

| Well we don’t have a colour printer on the desk but if we did it would be very expensive, yeah… But I think even if we had a colour printer I don’t think many GPs would be printing that kind of thing out, that is expensive as soon as you do a few of those.—GP M1 |

| Reflexive monitoring |

|---|

| but we haven’t monitored it in any formal way, so I only have anecdotal feedback really from prescribers—Stakeholder 10 |

| No, I am not, I am assuming that that’s going to come out of Public Health England, I am not doing any monitoring,—Stakeholder 5 |

| I think that’s the kind of thing we’re usually enthusiastic at the time and say, oh yes, that would be a good idea, but then we don’t take it forward because it’s not our idea and I suppose we can’t see immediate benefit.—GP M1 |

| we were able to highlight to them actually it wasn’t always appropriate, and we fed back to them, also the antibiotics that they were using, and then when we re-audited it actually there was a significant change in everyone’s practice really.—GP M9 |

| Now I am told that we will have some figures for those practices where we have delivered the workshop, the prescribing will be collected and then, yes, we will get that information maybe in six months’ time, has their prescribing gone down as compared to what it was previously?—Stakeholder 4 |

| We’re using that checklist alongside sending the GPs quarterly antibiotic prescribing data for their practice so that they can, hopefully, see that the use of the materials, implementing delayed prescribing strategies, use of the leaflet, to reflect and see whether that has had any impact on their prescribing as a practice.—Stakeholder 9 |

Conclusions

Summary

The TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit complemented existing activities to support appropriate antibiotic prescribing by addressing perceived patient expectations, patient education, clinician education and their behaviours. Cost of printing and lack of awareness were seen as key barriers to utilization of the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit, along with time and workload concerns, which could be partly addressed with structured and tailored action planning from CCGs. In 2014, AMS was not a priority for many practices as a result of other competing demands. Audits were seen as difficult due to inadequate Read coding.

Strengths and limitations

We used a mixture of interviews and focus groups to capture both individual and GP practice level engagement and use of TARGET. As we used workshop questionnaires and qualitative methods and participants may have used resources other than TARGET, a wide range of participants with varying AMS experience and opinions about TARGET contributed data. Of the GP staff that took part in this study, only 5% had not received a TARGET workshop and were not using the TARGET resources; however, a further 28% had received a TARGET workshop and had decided not to use TARGET; therefore, the data obtained from both of these groups provided a sufficient understanding of the decisions around why TARGET had not been implemented. We only interviewed four trainers, but we felt this gave us adequate feedback about the resource delivery as we also had the workshop questionnaire data. We obtained qualitative data from five nurses, which is representative of the proportion of nurse prescribers. We undertook telephone rather than face-to-face interviews, which could reduce data quality (7); however, telephone interviews greatly facilitated recruitment, and the breadth of data gathered supports this approach.

The focus of this study was to explore qualitatively the acceptability and implementation of the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit. Therefore, this study cannot comment on the effectiveness of the resources. Further research will be needed to evaluate the effectiveness of the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit and the individual resources.

This research was conducted in 2014 prior to the introduction of the NHS Quality Premium in March 2015 (8) and therefore was at a time when TARGET was comparatively less well known. Commissioners looking to implement TARGET may experience increased engagement and compliance as a result of the increased prioritization of AMS by the NHS, although further research would be needed to examine this potential effect on engagement.

Comparison with existing literature

Patient expectation for antimicrobials, time pressures and diagnostic uncertainty undermined implementation of another AMS intervention (9). Time pressure, difficulty in changing style of consultation and lack of familiarity with available resources were barriers to implementing the When Should I Worry booklet in primary care (10,11). The barriers to implementing TARGET were similar, revolving around lack of awareness, time, competing priorities, cost and GP prescribing inconsistencies. Research has shown that overall GP workload in England has increased by 16% from 2007 to 2014 (12); it is therefore unsurprising that GPs are reporting that time and workload are key barriers. A requirement for good coherence in the normalization of interventions was stressed in a Swedish study, in which GPs who didn’t feel AMR was an issue were less likely to follow guidelines (13). Certainly our participants were aware of the importance of AMR, and this was reinforced in the workshop; however, some reflected that it was not just their responsibility to improve prescribing. A public campaign is running within North West England through 2017 called ‘Keep Antibiotics Working’, this would help to influence patients opinions towards the necessity of antibiotics and facilitate use of resources.

A study exploring implementation of a smartphone app for antimicrobial prescribing found that adoption of the app was successful because the information was in a format that was easily accessible to prescribers (14). Our study indicates that difficulty accessing and lack of awareness of TARGET contributed to some of the aspects of lack of implementation, particularly for the Treating Your Infection leaflet. Positive attitudes towards an electronic prescribing intervention in primary care and perceptions that it would save time facilitated adoption (15). If participants appreciated the benefits of implementing TARGET, it increased favourable opinions towards it, particularly where they felt that it would reduce future consultations and decrease inconsistent prescribing.

Implications for research and/or practice

There are various changes that are recommended on the basis of our findings, to improve the TARGET toolkit and increase use (Table 4). To overcome the barriers identified, it is important for CCGs to undertake further promotion to increase awareness with those that are unfamiliar with all of the TARGET resources and how they can be implemented in a timely and cost-effective way and identifying individuals in each practice responsible for implementing specific resources. Prescribers would be more likely to use TARGET if they could see measurable benefits especially to workload, such as decreased future consultations, improved prescribing and increased patient satisfaction and self-care; these need highlighting during implementation and measuring through audit. We found evidence to suggest that active promotion by CCGs could also increase local use of TARGET resources within practices by highlighting the importance of AMS and raising the issue as a high priority. To help primary care clinicians from overprescribing cautiously to prevent hospital admissions, confidence needs to be increased to improve the quality of antibiotic prescribing. This could be achieved through promotion of the TARGET training resources and by sharing the Treating Your Infection leaflet highlighting safety netting advice. We will be updating the presentation to highlight the very small difference antibiotics make for most uncomplicated infections and the risk of complications if antibiotics are not prescribed.

Table 4.

Suggested improvements to TARGET resources (2014–2015)

| TARGET resource | Suggested improvements to be implemented |

|---|---|

| Interactive workshop presentation. | • Allocate time during the workshop to action plan the implementation of the TARGET Toolkit. • Include more clinical scenarios to facilitate discussion and engagement. • Provide less background on AMR and only focus on the key messages of AMR. • Highlight roles others are taking to combat AMR. • Highlight small benefit of antibiotics and complication rates without antibiotics. |

| Patient leaflets: Treating Your Infection. | • Try to integrate the leaflet onto GP systems. • Provide the leaflet in additional languages. • Explore creating a simplified version. |

| Audit toolkits. | • Increase awareness of the audits through increased promotion. • Computer suppliers or local commissioner digital or medicines team to facilitate Read coding of syndromes using templates to simplify audits. |

| National antibiotic management guidance. | • Emphasize clinical scenarios more in the workshop to promote adherence to antibiotic guidance. • CCGs may find that by providing the local guidance in flip chart format adherence may increase. |

| Training resources—for self directed learning. | • Action planning may help with time allocation to conducting online learning. • Increased promotion is necessary to increase awareness of the online learning modules. • Encouragement to undertake via local incentives. |

| Resources for clinical and waiting areas. | • Action planning will help with the implementation of these resources by identifying the responsible individual. |

| Self-assessment checklist. | • Increase awareness of this tool through promoting its use as a monitoring tool. |

Service evaluations of the TARGET resources should be encouraged so that positive or negative effects of the resources can be fed back to local practice staff.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Family Practice online.

Acknowledgements

The study team wish to thank all of the participants that agreed to take part in interviews or focus groups for the study. And to everyone who has assisted and advised along the way, particularly Marie-Jet Bekkers for undertaking most of the interviews and Graham Tanner, the project’s patient representative. We would also like to extend a large thanks to everyone involved in setting up and carrying out the workshops, especially Philippa Moore, Alison West, Anita Sharma, Tariq Sharif, Ivor Cartmill, Adam Simon, Thomas Daines, Sue Carter, Paul Clarke, Jen Whibley, Julie Sadler, Gloria Omisakin, Sarah Clarke and Paul Wilson.

Declaration

Funding: This work was supported by the Public Health England development fund 2013 no.158.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by Public Health England sponsorship review group, Cardiff university ethics board (13/58, 25-09-2013) and local NHS R&D departments. NHS REC approval was not required as patients did not participate. Interview and focus group participants gave informed written consent for audio recording, transcription and use of anonymized quotes in publications; participants were offered £40 incentive.

Conflict of interest: The authors MH, RO, CB, and MG report no conflicts of interest.

Disclosures: LJ and DL are involved in implementation of the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit and will be involved in future adaptations. Professor CMN led development of the TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit and Public Health England antibiotic guidance. NF led the development of the When should I worry Booklet that is available through the TARGET website.

References

- 1. The World Health Organisation. World Health Assembly Addresses Antimicrobial Resistance, Immunization Gaps and Malnutrition 2015; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/wha-25-may-2015/en/ (accessed on 28th April 2016).

- 2. Department of Health. UK 5 Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2013 to 2018 2013; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-5-year-antimicrobial-resistance-strategy-2013-to-2018 (accessed on 28th April 2016).

- 3. Public Health England. Training Resources: The TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit 2012; http://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/toolkits/~/link.aspx?_id=2FC34B3CA5B446F19CB795B37AFF5083&_z=z (accessed on 5th April 2017).

- 4. Bunten AK, Hawking MKD, McNulty CAM. Patient information can improve appropriate antibiotic prescribing. Nurs Pract 2015; 82: 61–3. [Google Scholar]

- 5. May CR, Mair F, Finch T, et al. . Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory. Implement Sci 2009; 4: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McNulty CAM, Hawking MKD, Lecky D, et al. . Effects of primary care antimicrobial stewardship outreach on antibiotic use by general practice staff: Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trial of the TARGET Antibiotics workshop. J Antimicrob Chemotherapy 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. Novick G. Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research?Res Nurs Health 2008; 31: 391–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. NHS England. Technical Guidance Annex B, Information on Quality Premium. 2016; https://www.england.nhs.uk/resources/resources-for-ccgs/ccg-out-tool/ccg-ois/qual-prem/. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ackerman SL, Gonzales R, Stahl MS, Metlay JP. One size does not fit all: evaluating an intervention to reduce antibiotic prescribing for acute bronchitis. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Francis NA, Butler CC, Hood K, Simpson S, Wood F, Nuttall J. Effect of using an interactive booklet about childhood respiratory tract infections in primary care consultations on reconsulting and antibiotic prescribing: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009; 339: b2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Francis NA, Phillips R, Wood F, Hood K, Simpson S, Butler CC. Parents’ and clinicians’ views of an interactive booklet about respiratory tract infections in children: a qualitative process evaluation of the EQUIP randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2013; 14: 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hobbs FDR, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, et al. ; National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007-14. Lancet 2016; 387(10035): 2323–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Björkman I, Berg J, Viberg N, Stålsby Lundborg C. Awareness of antibiotic resistance and antibiotic prescribing in UTI treatment: a qualitative study among primary care physicians in Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care 2013; 31(1): 50–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Charani E, Kyratsis Y, Lawson W, et al. . An analysis of the development and implementation of a smartphone application for the delivery of antimicrobial prescribing policy: lessons learnt. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68: 960–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Devine EB, Williams EC, Martin DP, et al. . Prescriber and staff perceptions of an electronic prescribing system in primary care: a qualitative assessment. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010; 10: 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.