Abstract

BACKGROUND

Sharing of participant-level clinical trial data has potential benefits, but concerns about potential harms to research participants have led some pharmaceutical sponsors and investigators to urge caution. Little is known about clinical trial participants’ perceptions of the risks of data sharing.

METHODS

We conducted a structured survey of 771 current and recent participants from a diverse sample of clinical trials at three academic medical centers in the United States. Surveys were distributed by mail (350 completed surveys) and in clinic waiting rooms (421 completed surveys) (overall response rate, 79%).

RESULTS

Less than 8% of respondents felt that the potential negative consequences of data sharing outweighed the benefits. A total of 93% were very or somewhat likely to allow their own data to be shared with university scientists, and 82% were very or somewhat likely to share with scientists in for-profit companies. Willingness to share data did not vary appreciably with the purpose for which the data would be used, with the exception that fewer participants were willing to share their data for use in litigation. The respondents’ greatest concerns were that data sharing might make others less willing to enroll in clinical trials (37% very or somewhat concerned), that data would be used for marketing purposes (34%), or that data could be stolen (30%). Less concern was expressed about discrimination (22%) and exploitation of data for profit (20%).

CONCLUSIONS

In our study, few clinical trial participants had strong concerns about the risks of data sharing. Provided that adequate security safeguards were in place, most participants were willing to share their data for a wide range of uses. (Funded by the Greenwall Foundation.)

We are rapidly moving toward a world in which broad sharing of participant-level clinical trial data is the norm.1–4 The European Medicines Agency has implemented a policy to expand public access to data concerning products it approves,5,6 the Food and Drug Administration is considering how to expand access to data pooled within a product class,7 major research sponsors8–12 and journal editors13 have begun promoting data sharing, and lawmakers’ interest14 has resulted in legislation authorizing the National Institutes of Health to require all of its grantees to share data.15,16 Pharmaceutical industry associations have committed to making data more accessible,17 and several data platforms are now available.11,18–21

Previous work has identified diverse potential benefits of expanding access to participant-level data.1,4,22 These benefits include deterring inaccurate reporting of trial results,4,23,24 accelerating scientific discovery,25 and exploring questions that are not answerable within individual trials.4,26 In addition, data sharing helps fulfill the ethical obligation to make the most of research participants’ contributions to science.13,27–30

Yet some investigators and industry sponsors of clinical trials have expressed hesitancy about the swift move toward broad data sharing. These groups have shifted from opposing data sharing to supporting it31,32; however, several concerns have led them to urge caution, limit what they share, and resist some initiatives as going too far.32,33 Chief among these are concerns about potential harm to research participants.17,32,34,35 Sponsors and investigators express worries that participants’ privacy cannot be adequately protected, particularly in light of the fact that experts have demonstrated that it is possible to reidentify participant-level data.35–39 Some pharmaceutical company representatives warn that the threat to privacy posed by data sharing will chill willingness to participate in trials, thereby delaying the availability of new therapies.36,38

It is unclear to what extent participants in clinical trials share these concerns. There is a large body of empirical literature concerning people’s preferences related to biobanking40,41 but not about clinical trials. When patient advocacy groups have spoken about data sharing, they have sometimes been challenged as parroting the views of pharmaceutical companies that financially support them rather than conveying trial participants’ views.42 One commentator recently remarked that in debates about data sharing, “Both sides claim to have the patient’s and the public’s best interests at heart, but not many partisans of either camp have asked patients what those interests are.”43 To investigate this issue, we surveyed a large sample of participants in a diverse group of clinical trials.

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

Survey participants had been enrolled, or were the parent or guardian of someone who had been enrolled, in an interventional clinical trial within the previous 2 years. We obtained agreement from nine principal investigators (PIs) in clinical trials at three academic medical centers to facilitate access to their trial participants, including one PI who provided access to all trials in the university’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

We aimed for a broadly representative sample of trials that would be sufficient to provide at least 1200 potential survey participants. We selected the PIs we approached on the basis of personal contacts and stressed our interest in ensuring representation of racial and ethnic minority groups and persons with major health problems.

The final sample included both community-based trials (e.g., involving smoking cessation or diabetes prevention) and hospital-based trials (e.g., involving cancer or kidney disease). Within these trials, all the participants were eligible for the survey unless the trial team judged them as having cognitive impairment or being unable to respond to questions in English. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Stanford and at the medical centers that provided access to the trial participants.

QUESTIONNAIRE DEVELOPMENT

A 10-page structured survey questionnaire was used to elicit clinical trial participants’ views on the sharing of data from clinical trials. Details of the survey development work, which included the use of focus groups, consultation with experts and community advisory boards, and pilot testing, are provided in Sections 2 and 5 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

The questionnaire provided plain-English definitions of clinical trial, data sharing, and clinical trial data (Section 6 in the Supplementary Appendix). It included reminders that the survey was asking about sharing of individual-level information about trial participants, not research results, and that respondents should assume that the data were deidentified.

SURVEY ADMINISTRATION

Clinical trial PIs chose from among three methods of survey delivery: email, regular mail, or in-person distribution in study clinic waiting rooms. Four PIs chose regular mail, four chose the clinic, and one used both. All surveys were completed on paper, and the clinic staff’s interaction with respondents was limited to a receptionist or research assistant handing out and collecting the questionnaires (Section 1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

The surveys were accompanied by informed consent information and a $40 gift card. The responses were identified by participant identification number only.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Responses were manually entered into a database in the Stanford University REDCap Survey system44 and analyzed with the use of Stata software, version 13 (StataCorp). In addition to univariate statistics and cross-tabulations, multivariable logistic-regression models were run to identify predictors of the expression of negative views of data sharing. The following outcomes were modeled: perceiving the potential negative consequences of data sharing to outweigh the benefits (either strongly, moderately, or a little); being somewhat or very unlikely to allow one’s own trial data to be shared with scientists in not-for-profit settings; and being somewhat or very unlikely to allow data to be shared with scientists in drug companies. To account for missing data, multiple imputation was performed with the Stata “mi” platform. Details of the model construction and regression results are provided in Sections 3 and 4 in the Supplementary Appendix.

RESULTS

SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS

Completed surveys were received from 771 of the 978 invited trial participants (79%) and included 350 mailed surveys and 421 surveys completed in the clinic (Section 1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Respondents were fairly evenly distributed across the three academic medical centers (33%, 27%, and 40%) and were drawn from 119 different trials. Percentages based on the 771 respondents have a 95% confidence interval no wider than ±3.6 percentage points.

Table 1, and Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix, show the characteristics of the sample. Within the previous 2 years, 42% of the respondents had participated in a clinical trial as a person with the health condition being studied, 55% as a healthy volunteer or person at risk for the studied health condition, and 3% as both. The two most common topics studied in the trials were diabetes and issues related to nutrition, weight, and vitamin supplementation. A total of 90% of respondents were trial participants themselves, and 7% were parents of participants. More than 94% of the respondents reported having had positive experiences as clinical trial participants. Half were motivated to participate in the trial by the prospect of a health benefit, 33% by altruism, and 16% by other factors.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics as Reported in the Survey.*

| Characteristic | No. of Participants/Total No. (%) (N = 771) |

|---|---|

| Female sex | 380/762 (49.9) |

| Age | |

| <25 yr | 63/762 (8.3) |

| 25–44 yr | 177/762 (23.2) |

| 45–64 yr | 286/762 (37.5) |

| ≥65 yr | 236/762 (31.0) |

| Hispanic ethnic group | 101/759 (13.3) |

| Race | |

| White | 518/768 (67.4) |

| Black or African American | 113/768 (14.7) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 51/768 (6.6) |

| Asian | 25/768 (3.3) |

| Other | 61/768 (7.9) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 40/752 (5.3) |

| High-school diploma | 125/752 (16.6) |

| Some college | 206/752 (27.4) |

| College degree | 238/752 (31.6) |

| Graduate degree | 143/752 (19.0) |

| Annual family income | |

| Less than $15,000 to $24,999 | 173/742 (23.3) |

| $25,000 to $54,999 | 206/742 (27.8) |

| $55,000 to $99,999 | 189/742 (25.5) |

| $100,000 or higher | 174/742 (23.5) |

| Health status | |

| Excellent | 168/757 (22.2) |

| Good | 420/757 (55.5) |

| Fair | 156/757 (20.6) |

| Poor | 13/757 (1.7) |

| Trial topic | |

| Nutrition, weight, or vitamins | 172/771 (22.3) |

| Diabetes | 172/771 (22.3) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 71/771 (9.2) |

| Aging, neurodegenerative disease, or memory | 64/771 (8.3) |

| Tobacco use | 52/771 (6.7) |

| Liver disease | 49/771 (6.4) |

| Mental illness | 41/771 (5.3) |

| Cancer | 39/771 (5.1) |

| Kidney disease | 26/771 (3.4) |

| Other | 85/771 (11.0) |

| Overall experience as a trial participant | |

| Very positive | 573/752 (76.2) |

| Somewhat positive | 136/752 (18.1) |

| Neither positive nor negative | 34/752 (4.5) |

| Somewhat negative | 9/752 (1.2) |

| Very negative | 0 |

All characteristics with exception of trial topic were reported by the participant in the survey. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. Further details are provided in Section 6 in the Supplementary Appendix.

PERCEIVED RISKS OF DATA SHARING

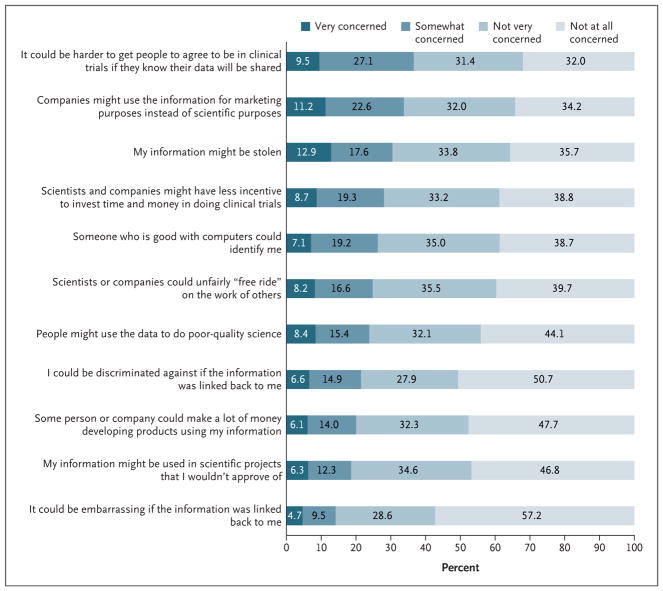

For 9 of 11 potential consequences of data sharing, less than 10% of the respondents said they were “very concerned” and less than one third were “very” or “somewhat” concerned about the risk (Fig. 1). A total of 20% to 26% of the respondents were very or somewhat concerned about discrimination, reidentification, and exploitation of data for profit. Respondents were more concerned that data sharing could deter people from enrolling in clinical trials (37%), that companies might use the information for marketing purposes (34%), or that their data could be stolen (30%). Asked to select the most important potential risk, respondents expressed divergent views, with the most common choices being that the information might be stolen (15%) or used for marketing purposes (11%) and that others might be more reluctant to enroll in clinical trials if they knew their data would be shared (10%) (Table S7 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 1. Level of Concern about Potential Consequences of Data Sharing.

Shown are the responses to an item worded as “How concerned are you about the following potential consequences of sharing anonymous, individual clinical trial data?” Numbers were rounded to the nearest tenth. The accuracy (95% confidence interval) of the percentages close to 50% is ±3.6 percentage points, diminishing to ±2.2 percentage points for percentages close to 10%.

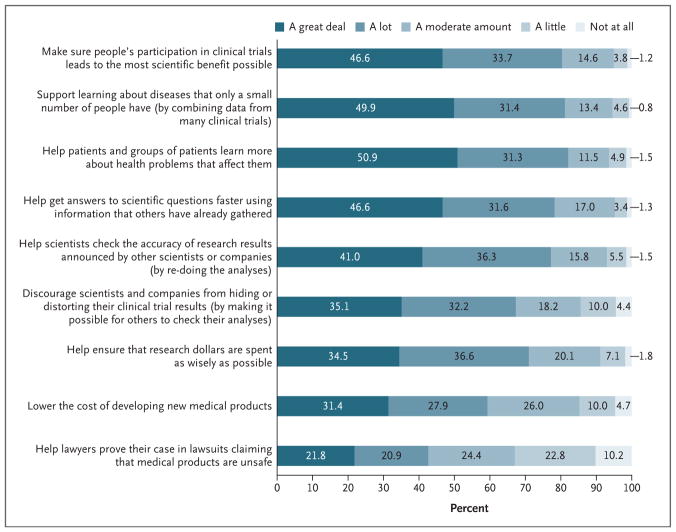

PERCEIVED BENEFITS OF DATA SHARING

Strong majorities of respondents (67% to 82%) believed that data sharing would yield “a great deal” or “a lot” of several benefits (Fig. 2). In contrast, 43% believed it would help lawyers prove their case in product liability lawsuits. When respondents were asked to choose the most important benefit of data sharing, the most popular choices were making sure people’s participation in clinical trials leads to the most scientific benefit possible (18%) and helping to get answers to scientific questions faster (17%) (Table S8 in the Supplementary Appendix). More than 85% of respondents expected that scientists in universities and other not-for-profit settings would benefit “a great deal” or “a lot” from data sharing; 81% of respondents had this expectation for physicians taking care of patients, 79% for companies developing medical products, and 72% for patients (Table S9 in the Supplementary Appendix)

Figure 2. Perceived Benefits of Data Sharing.

Shown are the responses to an item worded as “How much do you think sharing anonymous, individual clinical trial data can . . . .” Numbers were rounded to the nearest tenth. The accuracy (95% confidence interval) of percentages close to 50% is ±3.6 percentage points, diminishing to ±2.2 percentage points for percentages close to 10%.

OVERALL SUPPORT FOR DATA SHARING

In response to a question at the end of the survey, 82% of respondents indicated that they perceived that the benefits of data sharing outweighed the negative aspects, 8% felt the negative aspects outweighed the benefits, and 10% considered them equal (Table S10 in the Supplementary Appendix).

A total of 93% of respondents said they were very (69%) or moderately (24%) likely to allow their clinical trial data to be shared with scientists in universities and other not-for-profit organizations (Table 2), and 4% were very or somewhat unlikely to share. Although respondents had less trust in drug companies (18% trusted them a great deal or a lot) and health insurance companies (15%) than in universities (63%), 82% reported that they would be very or somewhat willing to share data with for-profit companies, whereas 8% were very or somewhat unwilling to share (Table 2, and Table S11 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 2.

Willingness of Clinical Trial Participants to Share Their Data, According to Type of Use and Recipient.*

| Type of Use or Recipient | Very Likely | Somewhat Likely | Neither Likely nor Unlikely | Somewhat Unlikely | Very Unlikely |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent of respondents | |||||

| Type of use | |||||

|

| |||||

| To help patients and groups of patients learn more about health problems that affect them | 77.8 | 18.8 | 2.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

|

| |||||

| To do research on health problems that affect my family or me | 78.3 | 17.1 | 3.2 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

|

| |||||

| To do research that will help others | 79.9 | 17.1 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

|

| |||||

| To help get answers to scientific questions faster using information that others have already gathered | 72.2 | 22.6 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 0.5 |

|

| |||||

| To help scientists check the accuracy of research results announced by other scientists or companies (by re-doing the analyses) | 70.9 | 22.6 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

|

| |||||

| To learn more about diseases that only a small number of people have (by combining data from many clinical trials) | 69.1 | 22.1 | 5.9 | 1.7 | 1.2 |

|

| |||||

| To help lawyers prove their case in lawsuits claiming that medical products are unsafe | 27.9 | 24.5 | 26.9 | 12.7 | 8.0 |

|

| |||||

| Recipient | |||||

|

| |||||

| Scientists in universities and other not-for-profit organizations | 69.2 | 24.0 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

|

| |||||

| Scientists in companies developing medical products, such as prescription drugs | 53.4 | 28.5 | 10.6 | 5.4 | 2.1 |

Shown are the responses to items worded as “How likely would you be to allow your anonymous, individual clinical trial data to be used in the following ways?” (for type of use) or “How likely would you be to allow your anonymous, individual clinical trial data to be shared with . . . .” (for recipient). Numbers were rounded to the nearest tenth. The accuracy (95% confidence interval) of percentages close to 50% is ±3.6 percentage points, diminishing to ±2.2 for percentages close to 10%.

Willingness to share data varied little according to the purpose for which it would be used — with the exception of its use in lawsuits, although a majority of respondents were still willing to share even for that purpose (Table 2). No appreciable differences were found between uses that did and uses that did not benefit the participant directly or between uses for verifying previous research results and uses for making new discoveries.

Among the write-in comments, the most dominant theme was the need to help others as much as possible. Many commenters expressed confidence in the deidentification of data. Several urged greater cooperation and less competition among scientists.

PREDICTORS OF ATTITUDES

In multivariable modeling, the likelihood that a respondent would feel that the negative aspects of data sharing outweighed the benefits was significantly higher among those who felt that other people generally could not be trusted (odds ratio, 2.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2 to 4.6) and among those who were concerned about the risk of reidentification (odds ratio, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.2 to 4.5) or about information theft (odds ratio, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.2 to 4.1) (Section 4 in the Supplementary Appendix). The only other significant predictor was having a college degree, which was associated with a lower likelihood of feeling that the negative aspects of data sharing outweighed the benefits (odds ratio, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.5).

A low level of trust in people was also a significant predictor of being somewhat or very unlikely to share one’s own data with scientists in not-for-profit contexts (odds ratio, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.6 to 8.3) or drug companies (odds ratio, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.3 to 4.8). Low trust in drug companies was a significant predictor of unwillingness to share data with drug-company scientists (odds ratio, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.4 to 4.2). Having a college degree was associated with a significantly lower likelihood of refusing to share data with not-for-profit scientists (odds ratio, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.10 to 0.78).

DISCUSSION

In this study assessing the views of clinical trial participants on the sharing of participant-level clinical trial data beyond genomic information, several key messages emerged. First, most of the clinical trial participants in our study believed that the benefits of data sharing outweighed the potential negative aspects and were willing to share their data. Their willingness to share was high regardless of the way in which the data would be used, with the exception of litigation, and it extended to uses that involved no prospect of direct benefit to themselves or their family members. Despite low levels of trust in pharmaceutical companies, most trial participants were willing to share their data with them.

The respondents’ lack of differentiation among different data users and uses contrasts with previous study findings related to biobank participation. Those studies consistently showed substantially less willingness to share biospecimens with researchers in for-profit companies than with university researchers.45–53 One study showed the same effect for sharing information from electronic health records (EHRs) for research purposes.54

The willingness of the respondents in our study to share clinical trial data was greater than that found in many previous studies that involved participants’ attitudes toward research use of biospecimens or EHR data.40,41,54–56 Expanding access to clinical trial data shares some ethical complexities with biobanking, such as how to obtain meaningful informed consent, but genetic information raises special concerns.45,57 On the other hand, clinical trial data include information from medical records and questionnaires that reveals much more about participants than biospecimens. Some such information — for example, sexual orientation or substance use — may carry serious social risks.38 A further consideration is that with rare exceptions,58 biobanking studies presume that an institutional review board will approve future uses of the data — a safeguard that may not be present for sharing of clinical trial data. Finally, biobanking and EHR studies have generally presumed that the data would be used by qualified researchers, but some proposals for “open access” data sharing are not so limited.1,4

The values and concerns of clinical trial participants may differ from those of the general public, patients in general, or other populations surveyed in biobanking and EHR studies. Clinical trial participants typically constitute a small proportion of the people who are eligible for participation and may represent those who are least bothered by data sharing and most enthusiastic about contributing to science. Their familiarity with physician-researchers may impart especially high trust in research and researchers.59 Indeed, nearly all of our respondents reported very positive experiences as trial participants.

Our findings are broadly consistent with other literature on engagement in clinical trials in underscoring the idea that altruism as well as self-regarding motivations influence participation decisions.60,61 In write-in comments, many respondents expressed the view that agreeing to broad use of their data was inherent in agreeing to participate in research.

A second finding of our study is that even when presented with a list of negative potential consequences, most trial participants do not express substantial concern about the risks of data sharing. On average, across the negative consequences they considered, approximately 8% of respondents were very concerned and 17% somewhat concerned. However, a substantial minority of respondents did express some concern, especially about discouraging others from volunteering for trials (37% somewhat or very concerned), having information used for marketing (34%), and having information stolen (31%). Many potential harms that trial sponsors and investigators worry a great deal about, such as reidentification and discrimination, were not of great concern to a sizable majority of participants, a finding that differs from surveys about biobanking that highlight these issues as leading concerns.62

Third, multivariable analysis revealed few differences in views across participant subgroups. Despite concern that distrust in research among African Americans may extend to data sharing,1,46,58,63 we found no significant differences according to race. Because few of our respondents expressed negative views of data sharing, only large subgroup differences were detectable.

Our study had limitations. The respondents were relatively healthy: approximately a quarter characterized their health status as fair or poor. Although health status was not a significant predictor of attitudes in our models, a less healthy group of respondents might have reported different views. Our response rate was high, but we cannot exclude the possibility of nonresponse bias. Some people may decline to enroll in clinical trials out of concern that their data might be shared, and they are not represented in our sample. The survey concepts were complex, and although we conducted pilot work to clarify questions, some respondents may have had comprehension difficulties or lacked sufficient understanding of data sharing to meaningfully assess the potential consequences. Finally, respondents’ actual willingness to share their data might be lower than their hypothetical willingness. Previous research on genomic data, however, has shown the reverse.59,62

Our findings suggest that concerns about trial participants’ attitudes toward data sharing invoked by companies and investigators who caution against it may be exaggerated. Participants perceive data sharing to have many benefits, and most are willing to share their data. Finally, participants’ concern about the use of their data for marketing is worth addressing. Data repositories could require data requesters to attest that no marketing use will occur, and consent documents could offer assurances about this requirement.

Reaching a world in which the sharing of clinical trial data is routine requires surmounting several challenges — financial, technical, and operational. But in this survey, participants’ objections to data sharing did not appear to be a sizable barrier.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the Greenwall Foundation. Research information technology used in the study was funded by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (Clinical and Translational Sciences Award UL1 TR001085, to Stanford University).

We thank the clinical trial principal investigators and teams for their generosity in facilitating access to the trial participants and administering the survey; Harry Selker, Edward Kuczynski, Anantha Shekhar, Laurie Trevino, and Brenda Hudson for connecting us with the trial teams; Sayeh Fattahi, Cynthia Rinaldo, and Quinn Walker for research assistance; and Jon Krosnick, Eric Campbell, Joe Ross, Jennifer Miller, Randy Stafford, and members of Dr. Stafford’s American Indian Community Action Board for feedback on earlier drafts of the survey questionnaire.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Sharing clinical trial data: maximizing benefits, minimizing risk. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zarin DA. Participant-level data and the new frontier in trial transparency. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:468–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1307268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loder E. Sharing data from clinical trials: where we are and what lies ahead. BMJ. 2013;347:f4794. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mello MM, Francer JK, Wilenzick M, Teden P, Bierer BE, Barnes M. Preparing for responsible sharing of clinical trial data. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1651–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhle1309073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Medicines Agency. Clinical data publication. ( http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/?curl=pages/special_topics/general/general_content_000555.jsp)

- 6.Davis AL, Miller JD. The European Medicines Agency and publication of clinical study reports: a challenge for the US FDA. JAMA. 2017;317:905–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration. Availability of masked and de-identified non-summary safety and efficacy data: request for comments. Fed Regist. 2013;78(107):33421–3. ( https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2013/06/04/2013-13083/availability-of-masked-and-de-identified-non-summary-safety-and-efficacy-data-request-for-comments) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coady SA, Wagner E. Sharing individual level data from observational studies and clinical trials: a perspective from NHLBI. Trials. 2013;14:201. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walport M, Brest P. Sharing research data to improve public health. Lancet. 2011;377:537–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jumbe NL, Murray JC, Kern S. Data sharing and inductive learning — toward healthy birth, growth, and development. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2415–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1605441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krumholz HM, Waldstreicher J. The Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project — a mechanism for data sharing. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:403–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green AK, Reeder-Hayes KE, Corty RW, et al. The Project Data Sphere initiative: accelerating cancer research by sharing data. Oncologist. 2015;20(5):464–e20. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taichman DB, Sahni P, Pinborg A, et al. Data sharing statements for clinical trials — a requirement of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2277–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1705439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren E. Strengthening research through data sharing. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:401–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.21st Century Cures Act, Pub. L. No. 114–255 § 2014 (2016).

- 16.Majumder MA, Guerrini CJ, Bollinger JM, Cook-Deegan R, McGuire AL. Sharing data under the 21st Century Cures Act. Genet Med. 2017;19:1289–94. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.PhRMA, EfPIA. Principles for responsible clinical trial data sharing. 2014 ( http://www.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/PhRMAPrinciplesForResponsibleClinicalTrialDataSharing.pdf)

- 18.Rockhold F, Nisen P, Freeman A. Data sharing at a crossroads. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1115–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1608086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krumholz HM, Gross CP, Blount KL, et al. Sea change in open science and data sharing: leadership by industry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:499–504. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bierer BE, Li R, Barnes M, Sim I. A global, neutral platform for sharing trial data. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2411–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1605348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strom BL, Buyse ME, Hughes J, Knoppers BM. Data sharing — is the juice worth the squeeze? N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1608–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1610336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eichler HG, Pétavy F, Pignatti F, Rasi G. Access to patient-level trial data — a boon to drug developers. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1577–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1310771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shining a light on trial data. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:371. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krumholz HM, Ross JS. A model for dissemination and independent analysis of industry data. JAMA. 2011;306:1593–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitty CJ, Mundel T, Farrar J, Heymann DL, Davies SC, Walport MJ. Providing incentives to share data early in health emergencies: the role of journal editors. Lancet. 2015;386:1797–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00758-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eichler HG, Abadie E, Breckenridge A, Leufkens H, Rasi G. Open clinical trial data for all? A view from regulators. PLoS Med. 2012;9(4):e1001202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gøtzsche PC. Why we need easy access to all data from all clinical trials and how to accomplish it. Trials. 2011;12:249. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemmens T. Pharmaceutical knowledge governance: a human rights perspective. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41:163–84. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauchner H, Golub RM, Fontanarosa PB. Data sharing: an ethical and scientific imperative. JAMA. 2016;315:1237–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertagnolli MM, Sartor O, Chabner BA, et al. Advantages of a truly open-access data-sharing model. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1178–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1702054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.PhRMA statement on clinical trials and Bad Pharma. Press release of PhRMA. 2013 Feb 5; ( http://www.phrma.org/press-release/phrma-statement-on-clinical-trials-and-bad-pharma)

- 32.Rathi V, Dzara K, Gross CP, et al. Sharing of clinical trial data among trialists: a cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2012;345:e7570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Statement on European General Court decision on EMA. Press release of PhRMA. 2013 Apr 30; ( http://www.phrma.org/press-release/phrma-statement-on-decision-of-the-european-general-court-on-ema-disclosure-of-company-data)

- 34.Berlin JA, Morris S, Rockhold F, Askie L, Ghersi D, Waldstreicher J. Bumps and bridges on the road to responsible sharing of clinical trial data. Clin Trials. 2014;11:7–12. doi: 10.1177/1740774513514497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaye J. The tension between data sharing and the protection of privacy in genomics research. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2012;13:415–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082410-101454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castellani J. Are clinical trial data shared sufficiently today? Yes BMJ. 2013;347:f1881. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Homer N, Szelinger S, Redman M, et al. Resolving individuals contributing trace amounts of DNA to highly complex mixtures using high-density SNP genotyping microarrays. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(8):e1000167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenblatt M, Jain SH, Cahill M. Sharing of clinical trial data: benefits, risks, and uniform principles. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:306–7. doi: 10.7326/M14-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alemayehu D, Anziano RJ, Levenstein M. Perspectives on clinical trial data transparency and disclosure. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;39:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garrison NA, Sathe NA, Antommaria AHM, et al. A systematic literature review of individuals’ perspectives on broad consent and data sharing in the United States. Genet Med. 2016;18:663–71. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shabani M, Bezuidenhout L, Borry P. Attitudes of research participants and the general public towards genomic data sharing: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2014;14:1053–65. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2014.961917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sample I. Big pharma mobilising patients in battle over drugs trials data. The Guardian. 2013 Jul 21; ( https://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/jul/21/big-pharma-secret-drugs-trials)

- 43.Haug CJ. Whose data are they anyway? Can a patient perspective advance the data-sharing debate? N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2203–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1704485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) — a meta-data-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pentz RD, Billot L, Wendler D. Research on stored biological samples: views of African American and White American cancer patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:733–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaufman DJ, Murphy-Bollinger J, Scott J, Hudson KL. Public opinion about the importance of privacy in biobank research. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:643–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Helft PR, Champion VL, Eckles R, Johnson CS, Meslin EM. Cancer patients’ attitudes toward future research uses of stored human biological materials. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2007;2:15–22. doi: 10.1525/jer.2007.2.3.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beskow LM, Dean E. Informed consent for biorepositories: assessing prospective participants’ understanding and opinions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1440–51. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gornick MC, Ryan KA, Kim SY. Impact of non-welfare interests on willingness to donate to biobanks: an experimental survey. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2014;9:22–33. doi: 10.1177/1556264614544277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Bares JM, Jarvik GP, Larson EB, Burke W. Genomic research and wide data sharing: views of prospective participants. Genet Med. 2010;12:486–95. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e38f9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogith D, Yusuf RA, Hovick SR, et al. Attitudes regarding privacy of genomic information in personalized cancer therapy. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e2):e320–e325. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long MD, Cadigan RJ, Cook SF, et al. Perceptions of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases on biobanking. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:132–8. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hapgood R, McCabe C, Shickle D. Public preferences for participation in a large DNA cohort study: a discrete choice experiment. HEDS discussion paper 04/05. 2004 ( http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10939/)

- 54.Grande D, Mitra N, Shah A, Wan F, Asch DA. Public preferences about secondary uses of electronic health information. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1798–806. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Truven Health Analytics, National Public Radio. Health poll: data privacy. 2014 Nov; ( https://truvenhealth.com/Portals/0/NPR-Truven-Health-Poll/NPRPulseDataPrivacy_Nov2014.pdf)

- 56.Luchenski SA, Reed JE, Marston C, Papoutsi C, Majeed A, Bell D. Patient and public views on electronic health records and their uses in the United kingdom: cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e160. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Melas PA, Sjöholm LK, Forsner T, et al. Examining the public refusal to consent to DNA biobanking: empirical data from a Swedish population-based study. J Med Ethics. 2010;36:93–8. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.032367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Storr CL, Or F, Eaton WW, Ialongo N. Genetic research participation in a young adult community sample. J Community Genet. 2014;5:363–75. doi: 10.1007/s12687-014-0191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnsson L, Helgesson G, Rafnar T, et al. Hypothetical and factual willingness to participate in biobank research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:1261–4. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stunkel L, Grady C. More than the money: a review of the literature examining healthy volunteer motivations. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32:342–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Truong TH, Weeks JC, Cook EF, Joffe S. Altruism among participants in cancer clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2011;8:616–23. doi: 10.1177/1740774511414444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oliver JM, Slashinski MJ, Wang T, Kelly PA, Hilsenbeck SG, McGuire AL. Balancing the risks and benefits of genomic data sharing: genome research participants’ perspectives. Public Health Genomics. 2012;15:106–14. doi: 10.1159/000334718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sanderson SC, Brothers KB, Mercaldo ND, et al. Public attitudes toward consent and data sharing in biobank research: a large multi-site experimental survey in the US. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100:414–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.