Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Revascularization surgery has been the standard treatment to prevent ischemic stroke in pediatric Moyamoya disease (MMD) patients with ischemic symptoms. However, perioperative complications, such as hyperperfusion syndrome, new infarct on imaging, or ischemic stroke, are inevitable. Remote ischemic conditioning (RIC) is a noninvasive and easy-to-use neuroprotective strategy, and it has potential effects on preventing hyperperfusion syndrome and ischemic infarction.

AIMS:

The aim of this study is to investigate the safety and efficacy of RIC in pediatric MMD patients undergoing revascularization surgery.

METHOD:

A total of 60 pediatric MMD patients with one or more ischemic symptoms will be recruited and allocated in 1:1 ratio to the RIC group and sham group, respectively. Both RIC and sham RIC will be performed twice daily for 7 consecutive days before revascularization surgery with different cuff pressures during the ischemia period (50 mmHg over-systolic blood pressure and 30 mmHg). Single photon emission computed tomography will be performed within 7 days preoperatively and 3 months postoperatively, respectively, to evaluate the cerebral perfusion status. Other outcomes, including safety, plasma biomarker, functional outcome, and the incidence of infarction and its size, will also be evaluated.

CONCLUSION:

This study will provide insights into the preliminary proof of principle, safety, and efficacy of RIC in pediatric MMD patients undergoing revascularization surgery therapy, and this data will provide parameters for future larger scale clinical trials if efficacious.

Keywords: Pediatric moyamoya disease, remote ischemic conditioning, revascularization therapy

Introduction

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a progressive idiopathic disease leading to recurrent stroke due to occlusion of the terminal segment of internal carotid arteries and an abnormal vascular network at the base of the brain.[1] The incidence of MMD is roughly 0.54/100,000 people but varies greatly by Region.[2] It is not an uncommon cause for pediatric stroke, and its incidence and prevalence have gradually increased.[3,4]

Revascularization surgery, which aims to augment intracranial blood flow using branches of the external carotid system, is the standard treatment to prevent ischemic stroke in symptomatic MMD with an ischemic presentation.[5] However, perioperative morbidity are inevitable. Younger MMD patients can have up to a 39% chance of having a preoperative stroke at a median of 3 months.[6] Hyperperfusion syndrome, a well-known phenomenon that causes postoperative neurologic changes, happens in 21.5% to 50% of MMD patients after revascularization therapy,[7,8,9,10] and diffusion-weighted imaging-defined infarct lesions are detected in 9.3% to 33.3% of patients.[11] To date, however, no effective strategy exists to prevent these complications.[12]

Remote ischemic conditioning (RIC) has been shown to provide myocardial benefit in children undergoing cardiac surgery.[13,14] Researchers found that that RIC was an effective strategy to improve cerebral perfusion and prevent stroke recurrence in patients with ischemic stroke.[15,16,17] Furthermore, in severe carotid artery stenosis patients undergoing stent placement, RIC was effective in preventing new infarcts and reducing infarct volume and might prevent hyperperfusion syndrome postoperatively in the first 48 h.[18] Symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis (ICAS) has also been found to benefit from RIC.[15]

However, whether RIC is safe and effective in protecting pediatric MMD patients undergoing revascularization therapy is still unknown.

Aims

The present study investigates the clinical effect of RIC in preventing perioperative complications in pediatric MMD patients undergoing revascularization surgery. The aims are to provide estimates on its magnitude of safety and efficacy and to inform about the values and design of subsequent large cohort clinical trials.

Methods and Design

Study design

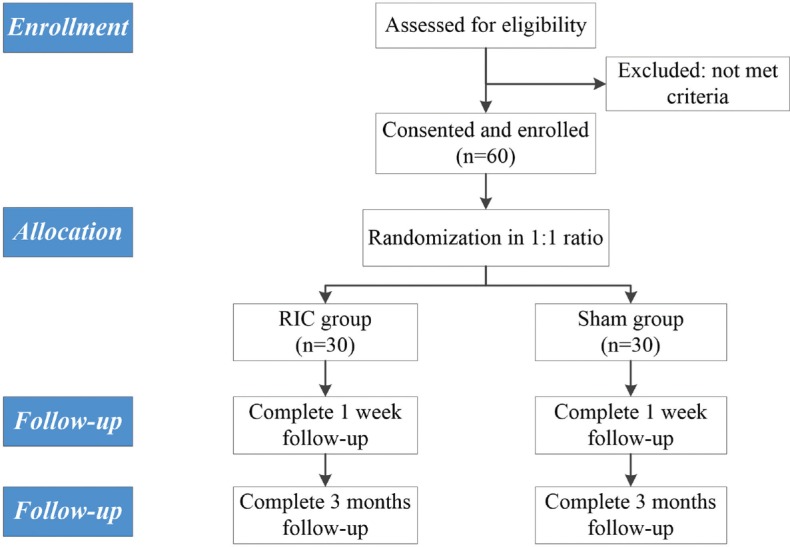

This is a multicenter, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group study [Flowchart 1]. Sixty patients will be recruited at Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University and The 307th Hospital of PLA, and randomized into the RIC group and the sham group.

Flowchart 1.

The flow diagram of this study. RIC: Remote ischemic conditioning

Subjects

The population of interest for the present study are pediatric MMD patients with ischemic presentation and treated with indirect revascularization therapy (encephalo-duro-arterio-synangiosis [EDAS] surgery).

Additional inclusion criteria included:

Age ≥0 and ≤18

All of the patients underwent digital subtraction angiography and met the current diagnostic criteria recommended by the Research Committee on MMD (Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan in 2012[19]

Suzuki stages concentrated in Stage III and IV[1]

Presentation with ischemic symptoms, such as transient ischemic attack (TIA), headache, seizure, hemorrhagic stroke, and ischemic stroke confirmed by MRI[20]

Informed consent obtained from patient or acceptable patient's surrogate.

Exclusion criteria included:

Severe hepatic or renal dysfunction

Severe hemostatic disorder or severe coagulation dysfunction

Patients with unilateral MMD or the presence of secondary moyamoya phenomenon caused by autoimmune disease, Down syndrome, neurofibromatosis, leptospiral infection, or previous skull-base radiation therapy

Any of the following cardiac disease - rheumatic mitral and or aortic stenosis, prosthetic heart valves, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, sick sinus syndrome, left atrial myxoma, patent foramen ovale, left ventricular mural thrombus or valvular vegetation, congestive heart failure, bacterial endocarditis, or any other cardiovascular condition interfering with participation

Serious, advanced, or terminal illnesses with anticipated life expectancy of less than one year

Patient participating in a study involving other drug or device trial study

Patients with existing neurological or psychiatric disease that would confound the neurological or functional evaluations

Unlikely to be available for follow-up for 3 months

Contraindication for RIC - severe soft-tissue injury, fracture, or peripheral vascular disease in the upper limbs.

Informed consent and ethical approval

Eligible patients were invited to take part in this study. The purpose and procedures were explained to the subjects, their legally authorized representative, or other authorized representative allowed by country regulations. A study information sheet, which is described in the details of the study, was provided. Patients who were willing to participate in this study were asked to sign the written consent form by themselves or their legally authorized delegates. This study was approved by the ethic committee of Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University and the 307th Hospital of PLA, respectively.

Randomization and treatment allocation

Sealed envelopes containing the treatment allocation were labeled with sequential numbers, and these envelopes were prepared by a researcher who was not involved in the delivery of the interventions or the screening of subjects. Allocation was performed using a permuted block randomization procedure to ensure the 1:1 ratio in each group. The allocation sequence was determined using a computerized random number generator with block sizes of four subjects. The allocation sequence was concealed from the investigators who were enrolling potential patients with a sequential number of opaque sealed envelopes. Envelopes were opened only after obtaining the informed consent.

Blinding

Sham RIC was used in the control group in this study. Therefore, all patients, investigators, surgeons were blinded to the allocation assignments.

Interventions

Patients in both groups received standard EDAS surgery. The EDAS surgery was conducted by experienced neurosurgeons who have performed over 100 EDAS surgeries. Patients allocated to the RIC group will undergo RIC procedure during which bilateral arm cuffs are inflated to a pressure of 50 mmHg over systolic blood pressure for five cycles of 5 min followed by 5 min of relaxation of the cuffs, and patients allocated to the sham group will undergo a sham RIC procedure during which bilateral arm cuffs are inflated to a pressure of 30 mmHg for five cycles of 5 min, followed by 5 min of relaxation of the cuffs. Both RIC and sham RIC will be performed by using an electric autocontrol device (Patent No. CN200820123637.X, China). RIC and sham RIC will be performed twice daily for consecutive 7 days before surgery.

RIC and sham RIC will be performed in the hospital under the supervision of an investigator. The RIC process can be ceased at any time if the subject experiences any discomfort or any condition that interfered with routine hospital care.

Outcome measurements

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is cerebral perfusion status in the operation side at 3 months posttreatment as assessed by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

The purpose of revascularization therapy is to improve cerebral perfusion status, which may prevent ischemia related symptoms. In this study, SPECT will be used to evaluate cerebral perfusion maps, regional cerebral blood flow will be evaluated with Technetium-99 m ethylene cysteine dimer.[21] SPECT will be performed within 7 days preoperation and 3 months postoperation.

Secondary outcomes

Safety of remote ischemic conditioning

We will evaluate the safety of RIC from the following aspects: (1) the objective signs of tissue or neurovascular injury caused by RIC procedure, including distal radial pulses, visual inspection for local edema, erythema, and/or skin lesions, and palpation for tenderness; (2) the number of patients not tolerating RIC procedure, and refuse to continue the RIC procedure; (3) the number of patients with any other adverse events related to RIC intervention as determined by the principle investigator.

Plasma biomarkers

In this study, we will detect the change of plasma biomarkers to detect the effects of RIC in this patients’ population. Brain injury biomarkers (S-100A4, MMP-9) and vascular biomarkers (basic fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor) will be detected. Blood samples will be drawn from cubital vein to test these biomarkers, and the points of measurement include baseline (pre-RIC treatment), 7 days after RIC treatment, 24 (−6/+12) hours and 72 ± 6 h postoperation. These samples will be centrifuged immediately after collection and stored at − 80 until batch evaluation.

National Institute of Health Stroke scale

National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is considered as a standardized assessment of neurological functions in the acute phase of stroke, and it is generally used to quantify patient's neurological impairments on 15 items in 11 fields of different neurological status.[22] An investigator blinded to the treatment assignment will observe all patients and rate each item on an ordinal scale with three to five levels. A maximum of 42 points can be achieved, where the higher score indicates more severe neurological dysfunction. NIHSS will be assessed by qualified investigator who are blinded to the treatment assignment at baseline (preoperation), 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and at 5–7 days or if discharged earlier.

Modified Rankin scale score

The Modified Rankin Scale Score (mRS) is the most comprehensive and most widely used primary outcome measurement to assess the neurological functional disability in contemporary acute stroke trials.[23,24,25,26] The mRS is an ordinal, graded interval scale that assigns patients among 7 global disability levels, which ranges from 0 (no symptom) to 5 (severe disability) and 6 (death).[27,28] We will use mRS to evaluate the degree of disability or dependence during daily activities. The mRS will be assessed by certified study investigator, who is blinded to the treatment assignment, at 90 days postoperation. The distribution of mRS will be compared between groups.

Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage

Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, including any subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with clinical symptoms and symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage. Head computed tomography or magnetic reasoning imaging (MRI) scan will be performed to confirm intracerebral hemorrhage, and the imaging will be evaluated by two independent neuroradiologists who are blinded to the study assignment.

Incidence of new perioperative infarct and its size

The incidence of new perioperative infarct may be the most direct outcome to assess the effect of RIC, and its size is also important. Head MRI is a precise method which is commonly used to evaluate infarct size. Therefore, incidence of infarct and their size will be assessed by MRI within 48 h postoperation, using standard protocols, including manual tracing of the infarct perimeter and semiautomated pixel thresholding.[29,30]

Angiographic outcome

Angiographic outcome will be assessed following Matsushima's criteria (proportion of the middle cerebral artery territory with revascularization from collaterals from the external carotid artery through the burr holes): Grade A: >2/3; Grade B: between 1/3 and 2/3; Grade C: <1/3. Both selective internal and external carotid angiography will be performed 9 months posttreatment.

Death and adverse event

All causes of death will be included to compute mortality at 90 days postoperation, and mortality will be compared between groups. Any adverse event will be reported and its relationship with the RIC intervention will be evaluated.

Sample size

Dobkin has shown that 15 patients per group are often adequate for determining whether a larger multicenter trial should be conducted.[31] Furthermore, Hertzog has suggested that 10–20 patients in each research group are sufficient to evaluate the feasibility in a pilot study.[32] Therefore, our goal is to recruit 30 MMD patients in each group. The results of this study will be used to compute sample size and conduct a power calculation to plan a large-scale trial.

Statistical analysis

All analyses will be done according to the intention-to-treat principle, which will include all patients enrolled into this trial. Per-protocol analyses, excluding patients who fail to complete the follow-up, will be managed as a supplement of the intention-to-treat analysis to further confirm the results.

For binary data, risk ratio and 95% of confidence interval will be calculated. For continuous data multivariate repeated measures or one-way analysis of variance analysis (assuming data are normally distributed) will be applied. For missing data at 1 and 3 months, we will conduct a sensitivity analysis and use multiple imputations to impute values for those with missing data for continuous data. For clinical events (e.g., hemorrhage stroke, recurrent stroke, and death), we will regard the patients lost to follow-up as no event happening in both groups.

All data will be analyzed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) with the significance level of P < 0.05 (two sides).

Discussion

Revascularization surgery can augment intracranial blood flow and prevent ischemic stroke in symptomatic MMD patients. 5-year risk of perioperative stroke or death following revascularization is 5.5% in one study. Furthermore, 91% of patients presenting with TIAs were free of TIAs at 1 year.[33]

However, hyperperfusion injury, brain infarct injury, and other complications are part of the disease course, which may attenuate the therapeutic effects of revascularization.[7,8,9,10,34] Furthermore, the natural progression of MMD is much more rapid in pediatric patients than in adults. Therefore, early intervention through revascularization surgery is beneficial in pediatric patients. In clinical practice, safe and effective strategies are urgently needed to prevent these complications, and further improve the therapeutic effects of revascularization therapy.

In children undergoing repair of congenital heart defects, RIC has been safely used to prevent myocardial enzyme elevations.[14] In infants undergoing open heart operation, researchers demonstrated the cardiopulmonary protective effects of RIC.[35] In addition, RIC has been demonstrated to benefit ischemic stroke patients without any related complications, and it has been reported to have potential protective effects in preventing hyperperfusion syndrome in patients undergoing carotid artery stenting and endarterectomy.[18,36]

As revascularization surgery of MMD shares common characteristics with carotid stenting, carotid endarterectomy, and cardiac surgery, it is reasonable to speculate that RIC can be safely applied and benefit MMD patients with the potential effects in reducing hyperperfusion syndrome and brain injury in those undergoing revascularization therapy, and promoting the recovery of blood flow. Similarly, ICAS has a similar intracranial stenotic pathogenesis with increased basal stroke and TIA rates in symptomatic patients. While ICAS has traditionally not responded to revascularization therapy, according to the Carotid Occlusion Surgery Study Randomized Trial, the Japanese EC-IC Bypass Trial does support revascularization surgery and new data on balloon angioplasty appears safe with 0% 30 days postoperative risk of stroke.[37] All of these procedures may benefit from preoperative patient RIC.

RIC for ICAS has been shown to increase the rate of long-term intracerebral collateral formation, and decrease 90 day recurrent stroke rates from 23 to 5%.[15] Mechanisms of RIC neural protection include mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling, calcium homeostasis in mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum related to calcium channel expression reduction, and favorable changes in calcium ATPase and reactive oxygen species levels.[38]

However, there are no previous studies focusing on the effects of RIC in pediatric MMD patients. The RIC treatment protocol is adapted from our previous study on carotid stenting.[18] Limitations of the study include small size, disease heterogeneity, and given the amount of brain surgical manipulation, biomarkers may not be accurate as in the CAS studies. In addition, even if this study demonstrates the protective effects of RIC in this patient population, the RIC treatment protocol used in this study might not be the optimal one and further iteration may be necessary given the findings in the CAS study, and numerous ICAS studies we are hopeful a positive impact will be demonstrated on patients with MMD.

Conclusion

The present study will provide insights into the preliminary proof of principle, safety, feasibility, and efficacy of RIC in pediatric MMD patients undergoing revascularization surgery therapy, and these data will provide valuable parameters for future larger clinical trials.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was funded by The National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2017YFC1308405), Chang Jiang Scholars Program (No. T2014251), Capital Health Research and Development of Special (2016-4-1032) and Beijing science and technology plan (D131100005313017).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Suzuki J, Takaku A. Cerebrovascular “moyamoya” disease. Disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:288–99. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480090076012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagiub M, Allarakhia I. Pediatric moyamoya disease. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:134–8. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.889170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakai K, Tamakoshi A, Ikezaki K, Fukui M, Kawamura T, Aoki R, et al. Epidemiological features of moyamoya disease in Japan: Findings from a Nationwide Survey. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99(Suppl 2):S1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(97)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim T, Lee H, Bang JS, Kwon OK, Hwang G, Oh CW, et al. Epidemiology of moyamoya disease in Korea: Based on National Health Insurance Service Data. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2015;57:390–5. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2015.57.6.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim T, Oh CW, Kwon OK, Hwang G, Kim JE, Kang HS, et al. Stroke prevention by direct revascularization for patients with adult-onset moyamoya disease presenting with ischemia. J Neurosurg. 2016;124:1788–93. doi: 10.3171/2015.6.JNS151105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SK, Seol HJ, Cho BK, Hwang YS, Lee DS, Wang KC, et al. Moyamoya disease among young patients: Its aggressive clinical course and the role of active surgical treatment. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:840–4. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000114140.41509.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JE, Oh CW, Kwon OK, Park SQ, Kim SE, Kim YK, et al. Transient hyperperfusion after superficial temporal artery/middle cerebral artery bypass surgery as a possible cause of postoperative transient neurological deterioration. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:580–6. doi: 10.1159/000132205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujimura M, Shimizu H, Inoue T, Mugikura S, Saito A, Tominaga T, et al. Significance of focal cerebral hyperperfusion as a cause of transient neurologic deterioration after extracranial-intracranial bypass for moyamoya disease: Comparative study with non-moyamoya patients using N-isopropyl-p-[(123) I] iodoamphetamine single-photon emission computed tomography. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:957–64. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318208f1da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimura M, Kaneta T, Mugikura S, Shimizu H, Tominaga T. Temporary neurologic deterioration due to cerebral hyperperfusion after superficial temporal artery-middle cerebral artery anastomosis in patients with adult-onset moyamoya disease. Surg Neurol. 2007;67:273–82. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchino H, Kuroda S, Hirata K, Shiga T, Houkin K, Tamaki N, et al. Predictors and clinical features of postoperative hyperperfusion after surgical revascularization for moyamoya disease: A serial single photon emission CT/positron emission tomography study. Stroke. 2012;43:2610–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.654723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funaki T, Takahashi JC, Takagi Y, Kikuchi T, Yoshida K, Mitsuhara T, et al. Unstable moyamoya disease: Clinical features and impact on perioperative ischemic complications. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:400–7. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS14231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamauchi S, Shichinohe H, Houkin K. Review of past and present research on experimental models of moyamoya disease. Brain Circ. 2015;1:88–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo W, Zhu M, Huang R, Zhang Y. A comparison of cardiac post-conditioning and remote pre-conditioning in paediatric cardiac surgery. Cardiol Young. 2011;21:266–70. doi: 10.1017/S1047951110001915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung MM, Kharbanda RK, Konstantinov IE, Shimizu M, Frndova H, Li J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of remote ischemic preconditioning on children undergoing cardiac surgery: First clinical application in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2277–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng R, Asmaro K, Meng L, Liu Y, Ma C, Xi C, et al. Upper limb ischemic preconditioning prevents recurrent stroke in intracranial arterial stenosis. Neurology. 2012;79:1853–61. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318271f76a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gidday JM. Cerebrovascular ischemic protection by pre- and post-conditioning. Brain Circ. 2015;1:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren C, Liu K, Cui X, Gao J, Ji X, Ding Y. Neural transmission pathways are involved in the neuroprotection induced by post but not per-ischemic limb remote conditioning. Brain Circ. 2016;1:160–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao W, Meng R, Ma C, Hou B, Jiao L, Zhu F, et al. Safety and efficacy of remote ischemic preconditioning in patients with severe carotid artery stenosis before carotid artery stenting: A proof-of-concept, randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2017;135:1325–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Research Committee on the Pathology and Treatment of Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis, Health Labour Sciences Research Grant for Research on Measures for Infractable Diseases. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of moyamoya disease (spontaneous occlusion of the circle of willis) Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2012;52:245–66. doi: 10.2176/nmc.52.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, Alberts MJ, Chaturvedi S, Feldmann E, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40:2276–93. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merhof D, Markiewicz PJ, Platsch G, Declerck J, Weih M, Kornhuber J, et al. Optimized data preprocessing for multivariate analysis applied to 99mTc-ECD SPECT data sets of Alzheimer's patients and asymptomatic controls. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:371–83. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer U, Arnold M, Nedeltchev K, Brekenfeld C, Ballinari P, Remonda L, et al. NIHSS score and arteriographic findings in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:2121–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000182099.04994.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, Dewey HM, Churilov L, Yassi N, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1009–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Eesa M, Rempel JL, Thornton J, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1019–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener HC, Levy EI, Pereira VM, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. T-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2285–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saver JL, Filip B, Hamilton S, Yanes A, Craig S, Cho M, et al. Improving the reliability of stroke disability grading in clinical trials and clinical practice: The rankin focused assessment (RFA) Stroke. 2010;41:992–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.571364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong KS, Saver JL. Quantifying the value of stroke disability outcomes: WHO global burden of disease project disability weights for each level of the modified rankin scale. Stroke. 2009;40:3828–33. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gavin CM, Smith CJ, Emsley HC, Hughes DG, Turnbull IW, Vail A, et al. Reliability of a semi-automated technique of cerebral infarct volume measurement with CT. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18:220–6. doi: 10.1159/000079957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Worp HB, Claus SP, Bär PR, Ramos LM, Algra A, van Gijn J, et al. Reproducibility of measurements of cerebral infarct volume on CT scans. Stroke. 2001;32:424–30. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobkin BH. Progressive staging of pilot studies to improve phase III trials for motor interventions. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23:197–206. doi: 10.1177/1545968309331863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31:180–91. doi: 10.1002/nur.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzman R, Lee M, Achrol A, Bell-Stephens T, Kelly M, Do HM, et al. Clinical outcome after 450 revascularization procedures for moyamoya disease. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:927–35. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.JNS081649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim T, Oh CW, Bang JS, Kim JE, Cho WS. Moyamoya disease: Treatment and outcomes. J Stroke. 2016;18:21–30. doi: 10.5853/jos.2015.01739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou W, Zeng D, Chen R, Liu J, Yang G, Liu P, et al. Limb ischemic preconditioning reduces heart and lung injury after an open heart operation in infants. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:22–9. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9536-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh SR, Nouraei SA, Tang TY, Sadat U, Carpenter RH, Gaunt ME, et al. Remote ischemic preconditioning for cerebral and cardiac protection during carotid endarterectomy: Results from a pilot randomized clinical trial. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2010;44:434–9. doi: 10.1177/1538574410369709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dumont TM, Sonig A, Mokin M, Eller JL, Sorkin GC, Snyder KV, et al. Submaximal angioplasty for symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis: A prospective phase I study. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:964–71. doi: 10.3171/2015.8.JNS15791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sisalli MJ, Annunziato L, Scorziello A. Novel cellular mechanisms for neuroprotection in ischemic preconditioning: A view from inside organelles. Front Neurol. 2015;6:115. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]