Abstract

In 2010, community based health insurance scheme (CBHIS) was launched in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Nigeria. Little is known about the preferences and perception of the rural dwellers of the FCT about the scheme. This study aimed to determine the preferences of healthcare consumers towards CBHIS in FCT. A descriptive cross sectional study of 287 household heads was done. Systematic random sampling was used. Information was collected using a semi-structured, interviewer administered questionnaire. Data was analysed with SPSS version 21. Male respondents were 175 (61%), 242 (84.3%) were aware of the existence of CBHIS, 126 (82%) also enrolled their dependents. Annual payment of health insurance premium was preferred by 91 (59.9%) of enrolled respondents, 92 (60.1%) enrolled in the scheme because they perceived it to be a cheap way to access healthcare. No proper understanding was the reason why 33 (28.4%) of those aware of the scheme did not enroll themselves or their dependents. Only 124 (55.1%) were satisfied with the overall services provided to them by their health care provider (HCP). More community enlightenment on CBHIS is required. There is a need to factor in the preferences of the community members into the FCTCBHIS to determine what community members are willing to pay for their healthcare premium and how making contributions will be convenient for them.

Key words: CBHIS, Health insurance, rural communities, knowledge, perception

Introduction

Healthcare systems in many developing countries have failed to provide its population with quality and affordable health services due to the poor state of public health services.1 The health sector is also under funded as an average of only 3.52% of the entire budget of the Nigerian government was spent on health between 2000 and 2004 which was below the 5% recommended by the World Health Organization.2,3 As a result of the state of health systems, there has been an increase in the cost of healthcare which has further impoverished the poor population who fund their healthcare needs through out of pocket payment.4 In recent years there has been a trend for many developing countries to move towards a new or expanded role for various forms of health insurance schemes as a form of health care financing in order to reduce the burden of high cost of out of pocket payment for health care and to attain universal coverage, Nigeria as a country is not excluded.5

The community based health insurance scheme (CBHIS) is a non-profit health insurance program for a cohesive group of households/individuals or occupation based groups, formed on the basis of ethics of mutual aid and the collective pooling of health risks in which members take part in its management.6,7 The CBHIS is one of the Informal sector health insurance programs of the National Health Insurance Scheme which was established by Act 35 of the 1999 of the Nigerian constitution. The scheme operates on the principal aim to reduce the high dependency on out-ofpocket (OOP) payments which accounts for more than 65% of all health expenditures in the form of user charges and co-payments, which disproportionately affect the poorest in society and has been recognized as an important tool for making health care affordable among the poorest.8-10

Government and communities in Sub- Saharan Africa have been seen to show interest in implementing the CBHIS.11-13 This is because CBHIS promises a glimpse of hope to the unending health inequality affecting most especially the rural part of the region, providing a means of achieving universal health coverage and this eagerness has resulted in the spread of CBHI schemes.1,14 Despite increasing support and spread of CBHIS as reported in several studies across Africa enrolment has remained low (22-24%) indicating that CBHIS has continued to fail to reach satisfactory levels of participation amongst targeted population, this could be as a result of poor awareness and sensitization to the targeted population and a lack of understanding of their expectation of the scheme.2,14-18

According to WHO, little attention is being paid to understanding consumers’ preferences in the implementation of CBHIS across the world and the case is not different as only few studies were found to have recently accessed consumers knowledge and perception on CBHIS in Africa.14,19,20 A study in Plateau State, Nigeria showed that 71% had good knowledge of CBHIS through mass media, however, there was no CBHIS scheme in the community and the entire state where this study was carried out.16 The other study found in Nigeria which evaluated the benefit healthcare consumers are willing to pay for, if CBHIS was eventually introduced excluded the communities in which CBHIS has been piloted.20 This study aimed to determine the preferences of a rural community on the CBHIS where the scheme has been implemented.

Materials and Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted from July to September 2014 in Gwagwalada area council which is one of the six Local Government Area Councils of the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria. Gwagwalada area council has an area of 1,043 km² and 104 communities which has an estimated 50,867 households and population of 201,496. Majority of its working population are in the informal sector dwelling in rural communities and involve in Fadama farming which is the main economic activity in the area.21

Study design

A descriptive cross sectional study design was used in this study. This study design was chosen as the most suitable considering the research questions and budget involved.

Sample size

Sample size calculation used based on Williams Cochran’s method for cross sectional survey.22 In order to achieve a confidence interval of 95% and a power of 80% and to be able to detect a margin of error of 5%, the study sample size was calculated based on the estimated prevalence rate of knowledge of CBHI of 25%.23 Assuming a non-response rate of 5%, the required minimum sample was 301 households.

Sampling method

To identify the individual households to participate in this survey, the FCT demographic and household survey listing of households was used as a sampling frame. The first household was identified using simple random sampling, after which a systematic random sampling was applied to identify the subsequent household until the required sample was obtained. Questionnaires were administered to household heads or their spouses, and in their absence, another senior household member. Eligibility of the individual household included in this survey was individuals aged 18 years or more, consenting and willing to respond to an interview.

Data collection

Data collection was through face-toface interviews using a structured pretested questionnaire that contained both structured and open-ended questions administered to household heads selected using simple random sampling.

The first part of the questionnaire was designed to capture data on socio-demographic characteristics. The second part of the questionnaire evaluated respondent’s knowledge on CBHIS depending on whether or not the respondent had heard of a CBHIS and classified as aware or unaware, enrolled or not enrolled and whether or not they have benefitted from the scheme in terms of service delivery. Only the knowledge of those who were aware of CBHIS was evaluated. The third part of the questionnaire evaluated community perception of CBHIS in terms of willingness to be involved in the scheme, satisfaction with service delivery, and payment of premium. An interpreter was also used to translate response from their local gbagyi language to English language.

Data analysis

Data collected were entered into a computer and analyzed using SPSS version 21.0.24 Descriptive statistics was employed to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to categorize households into wealth quintiles and inputs into the PCA were gotten from information on household items like ownership of house and other assets like stove, fan, refrigerator, radio, television, air conditioner, piped water in the household, generator, bicycle, motorcycle, upholstered chair, washing machine and sewing machine. Quintiles were used to calculate distribution cut points and each household head was assigned the wealth index score of his/her household. The quintiles were Q1=Poorest, Q2=Second, Q3=Middle, Q4=Fourth, Q5=Richest.25 Level of awareness was summarized using mean and standard deviation while satisfaction level was summarized using mean score of respondent’s satisfaction score of different healthcare services on likert scale of 1 to 5. Satisfaction score below the mean was classified as not satisfied and score above the mean classified as satisfied.

Ethical considerations

Permission was obtained from the FCT CBHIS Secretariat and Head of Department for health in Gwagwalada area council.

Results

A total of 301 questionnaires were distributed out of which 287 were properly filled and returned, this gave a response rate of 95.4 % and equals the originally calculated required sample size and so the data presented is based on the response of 287 respondents.

The socio-demographic characteristics of the 287 respondents is found in Table 1 with 115 (40.1%) in age group 30-39 years and the least 35(12.2%) in age group 20-29 years. There were 175 (61%) male respondents. Islam was practiced by 143 (49.8%). Gbagyi ethnic group were 151 (52.6%). The married respondents were 236 (82.2%) of the population. The mean household size was 6.5 and ranged from 4 to 21 with 190 (66%) having household size of 6 and above. Only 22 (7.7%) had secondary/tertiary education while 173 (60.35) never had formal education. Farming is the predominant occupation of the study population, posing as source of income to 140 (48.8%), 60 (20.9%) of the respondents didn’t have any source of income and only 13 (4.5%) have their income from livestock rearing. About 175 (63.4%) earn below the country’s minimum wage of 18,000 naira.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of Gwagwalada Area Council Resident, Abuja, 2014.

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age group in years | ||

| 20-29 | 35 | 12.2 |

| 30-39 | 115 | 40.1 |

| 40-49 | 87 | 30.3 |

| 50+ | 50 | 17.4 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 175 | 61.0 |

| Female | 112 | 39.0 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 121 | 42.2 |

| Islam | 143 | 49.8 |

| Traditional | 23 | 8.0 |

| Ethnic group | ||

| Igbo | 6 | 2.1 |

| Hausa | 94 | 32.8 |

| Fulani | 36 | 12.5 |

| Gbagi | 151 | 52.6 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 10 | 3.5 |

| Married | 236 | 82.2 |

| Divorced | 14 | 4.9 |

| Widowed | 27 | 9.4 |

| Level of Education Completed | ||

| No formal Education | 173 | 60.3 |

| Primary | 92 | 32.1 |

| Secondary/Tertiary | 22 | 7.7 |

| Household size | ||

| ≤5 | 97 | 33.8 |

| ≥6 | 190 | 66.2 |

| Main source of income | ||

| Farming | 140 | 48.8 |

| Livestock | 13 | 4.5 |

| Paid employment | 32 | 11.1 |

| Small business | 42 | 14.6 |

| No source of income | 60 | 20.9 |

| Monthly Income in naira (n=276) | ||

| <18000 | 175 | 63.4 |

| ≥18,000 and above | 101 | 36.6 |

| Wealth index | ||

| Poorest | 58 | 20.2 |

| Second quintile | 58 | 20.2 |

| Middle quintile | 56 | 19.5 |

| Forth quintile | 58 | 20.2 |

| Richest | 57 | 19.9 |

Table 2 shows the respondent’s knowledge and awareness of CBHIS. In all, 242 (84.3%) were aware of the existence of CBHIS. Among the respondents who were aware of CBHIS, 115 (47.5%) was through community sensitization, 13 (5.4%) and 68 (28.1%) were through radio and close relatives respectively. Table 2 also shows that 186 (76.9%) of the respondent have the knowledge that only the enrolled individual pay for the CBHIS and the premium paid is enough to provide healthcare for a one year period. In all, 54 (22.3%) have the knowledge that the enrolled individual pays their premium which is only a part of the total cost needed to provide care while the government pay the rest in form of subsidy.

Table 2.

Knowledge and awareness of CBHIS among Gwagwalada Area Council Resident, Abuja, 2014.

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness of CBHIS (n=287) | ||

| Yes | 242 | 84.3 |

| No | 45 | 15.7 |

| Awareness medium (n=242) | ||

| Radio | 13 | 5.4 |

| Health center | 46 | 19.0 |

| Close relative | 68 | 28.1 |

| Community sensitization programs | 115 | 47.5 |

| Knowledge of who pays for CBHIS (n=242) | ||

| Enrolled family | 186 | 76.9 |

| Government | 2 | 0.8 |

| Government and enrolled individual | 54 | 22.3 |

Enrollment status of sample population is presented in Table 3. The total number of respondent that were aware of the scheme was 242 out of which 152 (62.8%) enrolled into the scheme. 126 (82%) of those enrolled also enrolled their dependents while 26 (17.1%) did not enroll their dependents. Only 54 (35.5%) have enrolled to the scheme for more than one year. Annual payment of health insurance premium was preferred by 91 (59.9%) of enrolled respondents while only 138.6% preferred to pay quarterly. A greater number of the respondents were new to the scheme as 74 (48.4%) were not due for renewal of their healthcare premium. However, 51 (33.3%) had renewed their premium and only 28 (18.3%) who were due for renewal had not yet renewed their premium. Willingness to renew healthcare premium was shown by 129 (84.3%) of the enrolled population while 20 (13.1%) were not sure if they will renew or not and 4 (2.6%) were not willing to renew.

Table 3.

Enrolment into CBHIS in Gwagwalada Area Council, Abuja, 2014.

| Enrolment status | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Enrollment in CBHIS (n=242) | ||

| Yes | 152 | 62.8 |

| No | 90 | 37.2 |

| Dependents enrollment CBHIS (n=152) | ||

| Yes | 126 | 82.9 |

| No | 26 | 17.1 |

| Period of membership | ||

| < 6 months | 8 | 5.3 |

| 6-12 months | 90 | 59.2 |

| 13-24 months | 54 | 35.5 |

| Preferred mode of payment | ||

| Monthly | 27 | 17.8 |

| Quarterly | 13 | 8.6 |

| Bi-annually | 21 | 13.8 |

| Annually | 91 | 59.9 |

| Renewal of premium | ||

| Yes | 51 | 33.3 |

| No | 28 | 18.3 |

| Not due for renewal | 74 | 48.4 |

| Willingness to renew premium | ||

| Yes | 129 | 84.3 |

| No | 4 | 2.6 |

| Undecided | 20 | 13.1 |

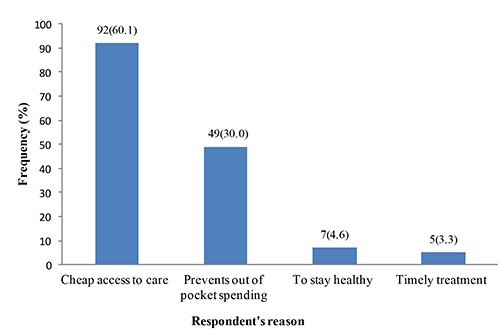

Figure 1 is a bar chart showing respondent’s reason for enrolling into CBHIS. More than half of the respondents 92 (60.1%) enrolled in the scheme because they perceived it to be a cheap way to access healthcare, 49 (32%) enrolled because they felt the scheme will help them prevent out of pocket spending for healthcare while 7 (4.6%) and 5 (3.3%) enrolled to stay healthy and get timely treatment respectively.

Figure 1.

Reason for enrolling in CBHIS in Gwagwalada Area Council, Abuja, 2014.

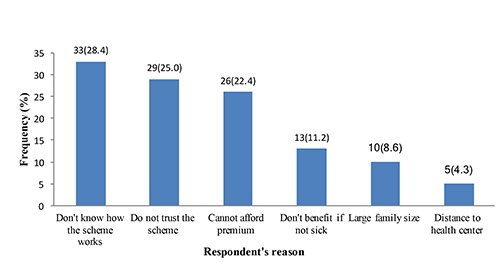

Figure 2 is showing the reasons why 116 of the respondents who were aware of CBHI did not enroll. As seen in the figure, 33 (28.4%) of those aware of the scheme did not enroll themselves or their dependents because they had no proper understanding on how the scheme works, 29 (25%) did not trust the scheme. Those who couldn’t afford the premium needed to be paid for them to enroll into the scheme were 26 (22.4%). The reason why 13 (11.2%) refused to enroll was because they don’t see how they benefit when do not fall sick at the end of their cover period. Only 10 (8.6%) could not register because they had large family size and 5 (4.3%) because of distance to the healthcare center.

Figure 2.

Reason for not enrolling in CBHIS in Gwagwalada Area Council, Abuja, 2014.

Table 4 shows respondent’s level of satisfaction with healthcare provider (HCP) services, 126 (56%) were satisfied with the services that involved drug provision and dispensing. More than half of the respondents 121 (53.8%) were satisfied with hospital services and 94 (41.8%) respondents were not satisfied with the hospital waiting time. In all, 124 (55.1%) were satisfied with the overall services provided to them by their HCP.

Table 4.

Respondent’s satisfaction with healthcare provider (HCP) services Gwagwalada Area Council, Abuja, 2014 (n=225).

| Satisfaction with HCP services | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Drugs Provision | ||

| Not satisfied | 99 | 44.0 |

| Satisfied | 126 | 56.0 |

| Hospital Services | ||

| Not satisfied | 104 | 46.2 |

| Satisfied | 121 | 53.8 |

| Waiting time | ||

| Not satisfied | 94 | 41.8 |

| Satisfied | 131 | 58.2 |

| Overall Satisfaction | ||

| Not satisfied | 101 | 44.9 |

| Satisfied | 124 | 55.1 |

Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine the preferences of a rural community in the Federal Capital Territory Abuja Nigeria in the community health insurance scheme (CBHIS). The socio-demographic characteristics of the study population revealed that there were more respondents in the age group of 30-39 years. This could be because this age group holds the youth of the community who are more enlightened and actively involved in community development programs. Unlike the study carried out in rural East and West Africa which recorded more female household heads in the study population.12,16 There were more male household heads in this study because in the Northern Nigerian context, the household heads are mostly males and it has been recorded that only 1 in 5 households are headed by female in Nigeria.25 About half of the study population practiced Islam religion and were of Gbagyi ethnic group as expected in rural setting of Abuja, Nigeria. As reported in some studies on CBHIS in Africa most of the respondents in this study were married and had little or no formal education.7,12,16,23 Household size of more than 6 was seen in about 66% of respondent because the study was carried out in a rural area which records more household size than the urban area.25

Awareness level of CBHIS in the community studied was high. This can be attributed to the constant sensitization and awareness campaigns organized in the communities by the FCT Health and Human Services Secretariat combined with the brilliant collaboration with the FCT-MDGs office who has initiated various health and agricultural programs in the communities before the introduction of CBHIS. This proves that the role of awareness and sensitization in CBHIS cannot be over emphasized. It gives an advantage to approach the rural community with a face they trust and are familiar with.

More than half of the household heads had enrolled themselves and their dependents. These figures are higher than the national health insurance scheme coverage level in Nigeria which is estimated as 5% of the population.18 The study population saw the need to enroll in CBHIS as it provided cheap access to healthcare and prevents out of pocket spending but there was lack of knowledge of how CBHIS is financed in the FCT as 80% of respondents felt that the money they pay fully provides the health services they receive from the CBHIS and were not aware that the government pays a huge part of the cost of care in form of subsidy, without which the scheme will not be sustainable. Similarly, some of the respondents were not enrolled in the scheme because of lack of proper understanding of how the CBHIS works and were of the opinion that the enrolled individual or family be refunded the unutilized premium paid for healthcare at the end of the cover period. This finding is synonymous to results from a study where the study population had inadequate knowledge of financing CBHIS.23

The price for health insurance was perceived to be high by some of the respondent this is because the study population were poor and 63.4% earn below the country’s minimum wage of 18,000 naira from mostly farming coupled with the design of CBHIS that uses the family as a unit of enrollment which makes it difficult for the poor population to register themselves and their dependents. High price for health insurance being a barrier for rural communities to enroll into CBHIS was also reported in qualitative studies from Senegal, Uganda and Kenya.12,15,26 Another study went ahead to suggest possible premium exemption or waivers for the poorest of the community members as an assurance for equitable enrollment into health insurance schemes.7

The primary healthcare center (PHC) the only public health facility in most rural communities and serves as the first point of healthcare contact to about 83% of respondents of this study when they fall ill but access to this PHC is actually limited as only 48.2% use the services of the PHC 5-10 times a year and just a few had been referred to the only general hospital in the area council. Presence of a healthcare facility in the community where the CBHIS is a critical factor for community members to be involved in the scheme but Gwagwalada area council where this study was conducted has PHC in only 29 out of 104 communities (FCT Baseline data on health services) and as expected, some respondents gave distance to PHC as their reason for not getting involved in CBHIS because they had to travel to a neighboring community to receive healthcare. This shows poor access and inequitable distribution of healthcare facilities and the people in the rural communities are disproportionately affected like in studies from some other African countries. 12,19,26 Despite poor access to PHC, more than half of the respondents were satisfied with PHC services. This could be because people in this part of the country are ignorant of what their health rights are coupled with the failing health system and the community members perceived that some form of cheap health care is better than none at all.

Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest that although there is a high level of awareness of CBHIS among the study population but there is misconception on how the scheme is financed as community members are under the impression that the premium paid provides the healthcare they receive under the scheme and are not aware of the subsidy paid by the government. There exists a lack of understanding of the principle of risk pooling on which health insurance operates by the community who expects a refund for unutilized health premium. The community members perceive the CBHIS as affordable and protect them from out of pocket payment; the reason behind high enrolment. On the other hand, lack of understanding on how the scheme works, lack of trust and inability to pay premium were hindrances to becoming members of CBHIS by some community members.

Recommendation

Increased access to healthcare facility and improved quality of health services particularly in drug availability, infrastructure and hospital personnel will go a long way to sustain the existence of CBHIS. The Nigerian government needs to dedicate more resources to bridge the gap created by lack of health care centers in the community and improve the bad state of the existing ones in order to keep the CBHIS running and achieve universal health coverage. Comprehensive awareness campaign should be carried put using various medium of awareness to reach out to the community members because people are likely to accept a program if only they understand key concepts and how the program actually runs. Other CBHIS programs should emulate the strategy used by the FCT-CBHIS to create awareness and acceptability of the scheme by going into the community through already established programs and people they trust.

There is a need to factor in the preferences of the community members into the FCT-CBHIS to determine what community members are willing to pay for their healthcare premium and how making contributions will be convenient for them.

Funding Statement

Funding: none.

References

- 1.WHO. The world health report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. Available from: www.who.int/whr/2010/10_summary_en.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ngowu R, Larson JS, Kim MS. Reducing child mortality in Nigeria: A case study of immunization and systemic factors. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falegan IJ. Healthcare financing in the developing world: is Nigeria’s National Health Insurance Scheme a Viable Option? Jos J Med 2008;3:5-6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meessen B, Van Damme W, Tahobya CK, Tibouti A. Poverty and user fees for public health care in low-income countries: lesion from Uganda and Cambodia. Lancet 2006;368:2253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagstaff A. Social Health Insurance Re-examined. Health Econ 2010;19:503-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrin G, Waelkens MP, Criel B. Community-based health insurance in developing countries: a study of its contribution to the performance of health financing systems. Trop Med Int Health 2005;10:799-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Njoroge K, Haron N. Community based health insurance schemes: Lesson from rural Kenya. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25:192-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sepehri A, Sarma S, Simpson W. Health Economics. Does non-profit health insurance reduce financial burden? Evidence from the Vietnam Living Standards Survey Panel 2006;15:603-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jutting JP. The Impact of Health Insurance on the Access to Health Care and Financial Protection in Rural Developing Countries: The Example of Senegal. Health, Nutrition and Population. Discussion Paper, Washington. The World Bank. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jutting JP. Do Community-based health insurance schemes improve poor people’s access to health care? Evidence from rural Senegal. World Dev 2004;32:273-88. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noubiap JJN, Joko WYA, Obama JMN, Bigna JJR. Community-based health insurance knowledge, concern, preferences, and financial planning for health care among informal sector workers in a health district of Douala, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J 2013;16:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jehu-Appiah C, Aryeetey G, Agyepong I, et al. Household perceptions and their implications for enrolment in the National Health Insurance Scheme in Ghana. Health Policy Planning 2012;27:222-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onwujekwe O, Onoka C, Uzochukwu B, et al. Preferences for benefit packages for community-based health insurance: an exploratory study in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulupi S, Kirigia D, Chuma J. Community perceptions of health insurance and their preferred design features: implications for the design of universal health coverage reforms in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noubiap JJ, Joko WV, Obama JM, et al. Community-based health insurance knowledge, concern, preferences and financial planning for health care among informal sector workers in a health district of Douala, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J 2013;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uzochukwu BSC, Onwujekwe OE, Eze S, et al. Community Based Health Insurance Scheme in Anambra State, Nigeria: an analysis of policy development, implementation and equity effects. Consortium Res Equitable Health Systems 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon J, Tenkorang EY, Luginaah I. Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme: a national level investigation of members’ perceptions of service provision. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afolabi MO, Daropale VO, Irinoye AI, Adegoke AA. Health-seeking behaviour and student perception of health care services in a university community in Nigeria. Health 2013;5:817-24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McIntyre D, Garshong B, Mtei G, et al. Beyond fragmentation and towards universal coverage: insights from Ghana, South Africa and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:871-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onwujekwe O, Onoka C, Uzochukwu B, et al. Is community-based health insurance an equitable strategy for paying for healthcare? Experiences from southeast Nigeria. Health Policy 2009;92:96-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Federal Capital Territory (FCT). Demographic and Household Survey tool. 2011. [28/09/2014]. Available from: http://fctsurvey.org.ng/. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. 3rd ed. ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banwat ME, Agbo HA, Hassan Z, Lassa S, Osagie IA, Ozoilo JU, et al. Community based health insurance knowledge and willingness to pay; A survey of a rural community in North Central zone of Nigeria. Jos J Med 2012;6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 21.0. IBM Corp. Released 2012. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- 25.NPC ICF Macro. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Abuja, Nigeria: National Population Commission and ICF Macro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekman B. Community-based health insurance in low-income countries a systematic review of evidence. Health Policy Planning 2004;19:249-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]