Abstract

OBJECTIVES

A lack of focus on variation in engagement among cancer populations of differing developmental stages led us to examine the associations between patient engagement, the patient-provider relationship, cognitive development, readiness to transition to adulthood (transitional readiness) and perceived quality of care.

METHODS

A sample of 101 adolescent cancer patients (diagnosed 10–20 years) completed survey items concerning patient engagement, dimensions of the patient-provider relationship, cognitive development, transitional readiness, and demographic characteristics using an iPad/tablet during a routine clinic visit.

RESULTS

Patient engagement was not significantly associated with perceived quality of care (b = .02, 95% CI: −0.06, 0.11). Instead, adolescents with providers that supported their independence (b = .34, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.52) were significantly more likely to perceive higher quality care.

CONCLUSION

Supportive patient-provider relationships are an integral part of adolescents’ perceptions of quality of care. Adolescents are still gaining important skills for navigating the medical system, and the patient-provider relationship may provide an important scaffolding relationship to help adolescents build independence in their treatment experience.

PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS

Identifying potential mechanisms through which adolescents can provide their opinion, ask questions, and participate in their treatment plan will help in supporting adolescent independence and improve quality of care.

Keywords: Quality of care, patient engagement, adolescent cancer, patient-provider relationship

1. Introduction

Adolescents with cancer report feeling out of place and without a home in an oncology setting that is usually geared towards younger children or older adults [1,2]. While the American Society of Clinical Oncology [3] has highlighted the need for improvement in quality of care, little attention has been paid to how perceptions of quality of care may vary in patients of different developmental stages. The Institute of Medicine [4] developed a framework for improving the quality of cancer care in the United States that is centered around patient engagement as the primary driving force. Engaged patients are able and willing to manage their own healthcare [5], are more likely to receive recommended screening tests, have lower medical costs, engage in health enhancing self-management behaviors, and report higher quality care [6–8]. Our paper will focus on exploring quality of care in the adolescent developmental stage (defined as ages 10–20 years) because it represents a stage of life where individuals change more than any other, outside of infancy, and these changes directly impact an individual’s ability to engage in their healthcare [9].

Changes in brain structure occur gradually across adolescence and into young adulthood. Information processing speed, the capacity to plan ahead, and the ability to consider multiple sources of information in decision-making develop throughout adolescence [9–14]. Cognitive function develops simultaneously with changes in the parent-child relationship [15–18], increases and then decreases in risk-taking and sensation-seeking behaviors [9,19], and improvements in emotion regulation [20]. One of the primary ways through which patients engage in their healthcare is through the medical decision-making process, a complex and emotionally-taxing experience. The numerous developmental changes adolescents are experiencing may make it difficult for them to participate in some aspects of medical decision-making, like the decision to pursue a specific course of treatment, without the help of a parent or healthcare provider.

The Institute of Medicine’s [4] framework emphasizes the patient-provider relationship as the primary mechanism through which we can increase patient engagement and ultimately improve quality of care. The current literature is limited on a clear understanding of the important dimensions of the patient-provider relationship in adolescent oncology, and if this relationship functions the same as it does in adult cancer populations [21]. The limited research suggests adolescents want to play a role in treatment decision-making, receive developmentally appropriate information, and feel like their values are being respected [2,22–24]. These preferences represent aspects of patient engagement, but it is unclear how the patient-provider relationship may be able to support these preferences considering the cognitive and emotion regulation skills adolescents are continuing to develop.

The purpose of this study was to examine the association between patient engagement and perceived quality of care in adolescent cancer patients. We defined adolescent cancer patients as individuals in their second decade of life and diagnosed between the ages of 10–20 to capture patients in the middle of adolescence as well as those transitioning in and out of this developmental stage [9]. We hypothesized that adolescents with more engagement will perceive higher levels of quality of care. The patient-provider relationship has been conceptualized as the primary mechanism through which patient engagement can be increased, and there is a lack of a clear understanding of how this relationship is structured in adolescent cancer care [21]. Therefore, a secondary aim of this study was to explore the relationship between different dimensions of the patient-provider relationship and perceived quality of care in adolescent cancer patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were eligible for study inclusion if they had a recent cancer diagnosis (either initial diagnosis or recurrence) at least 3 months previously at the age of 10 to 20 years, were treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation, had a reading and writing knowledge of English, and were either receiving therapy or less than 2 years from the end of therapy. The age range of 10 to 20 years of age at diagnosis was chosen to account for developmental changes that occur across this time, the legal implications of minor patients, and cross-cultural variations in the definition of adolescent patients [25]. Patients were excluded if they had a neurodevelopmental disorder or a physical disability that would prevent them from completing the survey (e.g. blindness).

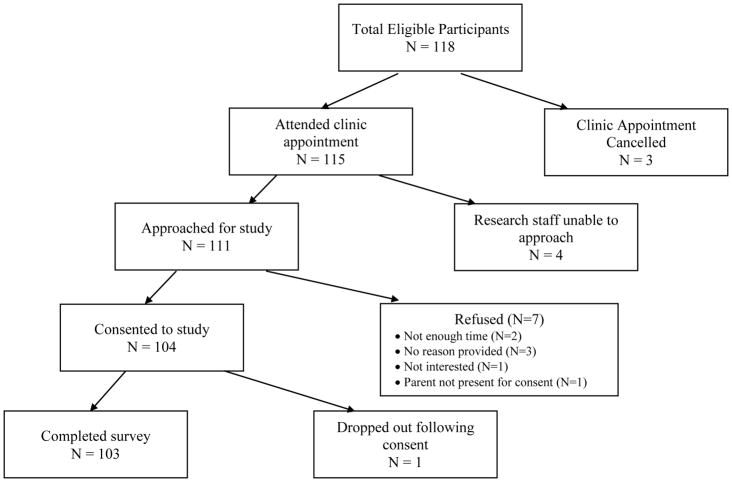

Eligibility for the study was determined via chart review by a member of the research team or clinical staff at the two recruitment sites. A total of 118 participants fit the inclusion criteria, and 111 were approached concerning the study. Of the 111 approached, 104 individuals agreed to participate and 103 completed the survey (Figure 1). The final participation rate for the survey was 92.3%.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study recruitment process, and reasons for not enrolling in the study

2.2. Recruitment and Data Collection

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was received by Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, and honored by the Yale Medical School IRB and the University of Connecticut IRB. A member of the clinical staff or research team screened the daily appointments for eligible participants, and approached eligible participants during their routine clinic visit. If participants expressed interest in the study, the principal investigator or other member of the research team conducted the consent and assent process and administered the survey using an iPad/tablet.

The anonymous survey was developed using Qualtrics; IP addresses were not collected and email addresses were not linked to individual survey responses. Parental consent and participant assent (when applicable) was documented within the survey, and participants were not able to access the survey items without first consenting to participation. Participants completed the survey in private areas of the clinic with a parent or guardian present if the participant was under the age of 18. Participants answered the questions from their perspective, but were provided the option to ask a member of the research team or their parent/guardian for help if needed. Participants were also provided the option to skip any questions that they were uncomfortable answering. The survey took an average of 10 to 15 minutes to complete, and participants received a $20 Amazon gift card for participation.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic and health information

Demographi c and health characteristics were assessed in the online survey via adolescent’s self-report. Characteristics assessed included current age, gender, education, racial/ethnic group, study site, cancer diagnosis, and age at diagnosis. Treatment history was measured using a single item that listed the following treatment options: chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, bone marrow transplant, or other treatment. Adolescents were asked to select all types of treatment they received. In our analysis, we examined each type of treatment as a separate, dichotomous variable where each participant was coded as either 0 (did not receive treatment) or 1 (received treatment). Recurrence history was assessed via a single, dichotomous item that asked adolescents if they had had a recurrence of their cancer (yes or no response options). Adolescents were coded as 0 (no recurrence) or 1 (recurrence).

2.3.3. Quality of care

Perceived quality of care was measured using a modified, four-item measure from the Experience of Care Subscale in the Youth Engagement with Health Services (YEHS!) survey [26]. Items were modified to focus explicitly on the oncology setting. For example: “During cancer treatment, did your oncologist or other members of your cancer care team listen carefully to you?” Participants responded using a 4-point Likert scale with responses ranging from 1= Strongly disagree to 4= Strongly agree. The scores were summed across the four items with higher scores (Range: 4–16) indicating a perception of higher quality of care. Internal consistency in the present sample was satisfactory, Cronbach’s α = .72.

2.3.3. Patient engagement

A modified version of the Health Self-Efficacy subscale of the Youth Engagement with Health Services (YEHS!) survey was used to evaluate patient engagement [26]. The survey was originally developed for use with healthy adolescents, so items were modified or removed to focus explicitly on care received in the oncology setting. For example: “I have a safe and trusting relationship with at least one member of my cancer care team.” The Health Self-Efficacy subscale included five items, and participants were asked to respond to each item using a 4-point Likert response scale with 1= Strongly disagree, 2= Somewhat disagree, 3= Somewhat agree, and 4= Strongly agree. The five items were summed to create a patient engagement score, and higher scores (Range: 5–20) represented more patient engagement. Internal consistency for the present sample was fair, Cronbach’s α = .76.

2.3.4. Patient-provider relationship

We assessed dimensions of the patient-provider relationship using three subscales developed as part of the current research study. The dimensions of the patient-provider relationship were identified through principal axis factor analysis utilizing promax rotation to allow the factors to be correlated, and the final solution specified a three-factor structure and retained 13 items (results of the exploratory factor analysis available in the Appendix). The 13-item measure (Cronbach’s α = 0.88) examines three dimensions of the patient-provider relationship: Supporting Independence (6 items; Range: 0–24; Cronbach’s α = .89; Example item: Talk to you honestly), Family-Centered Communication (4 items; Range: 0–16; Cronbach’s α = .73; Example item: Give you and your parent(s) written information about your treatment), and Respectful Relationships (3 items; Range: 0–12; Cronbach’s α = .66; Example item: Treat you as an individual). Items were chosen from the Give Youth a Voice (GYV) questionnaire [27] and the Measure of Processes of Care (MPOC-20) scale [28]. Items from the MPOC-20 were modified to elicit the adolescents’ perspective as the measure was originally created for use with parents, and the response options were modified from a 7-point scale to a 4-point Likert scale (1=Never, 2=Sometimes, 3=Most of the time, and 4=All the time; participants were also able to select “Does Not Apply to Me”) based on feedback gathered in pilot testing with 4 adolescents (ages 10–17 years). Scores for each subscale were summed across items in each subscale (Does Not Apply to Me was given a score of 0 [27]), with higher scores indicating higher presence of these dimensions in the patient-provider relationship.

2.3.5. Cognitive development

Cognitive development was measured using the Cognitive Autonomy and Self-Evaluation (CASE) Inventory [29]. Fourteen items were chosen from the decision making and evaluative thinking subscales of the larger inventory, and participants were asked to respond to each item on a 4-point response scale: never, sometimes, often, and always. For example: “I think of all possible risks before acting on a situation.” Scores were summed across the 14 items, and scores could range from 14 to 56 with higher scores indicating higher cognitive autonomy. Internal consistency for the CASE Inventory in the current sample was good, Cronbach’s α = .85.

2.3.6. Transitional readiness

A modified version of the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) was used [30]. The TRAQ was developed to assess the readiness of young adults with special healthcare needs to transition to adult healthcare services and independent living. For example: “Do you fill out the medical history form, including a list of your allergies.”

The measure included 8 items, and participants were asked to respond to each item using a 4-point Likert scale: never, sometimes, often, always. Participants were also able to select “My parent/guardian does this” for all 8 items, and “Does not apply to me” for some of the items. Scores for each item were dichotomized between participants indicating they never did an item, a parent/guardian did the item, or it did not apply to them and participants indicating that they did the item at any level. The dichotomized variables were then summed across all 8 items, and scores could range from 0 to 8. Higher scores indicated participant’s increased readiness to transition to independent living.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were assessed using basic descriptive statistics. T-tests, ANOVAs, and Pearson correlations were used to examine any significant bivariate differences in patient engagement, supporting independence, family-centered communication, respectful relationships, cognitive development, transitional readiness, and perceived quality of care. We also used bi-variate tests to identify control variables to include in the regression models. Demographic (age, gender, race/ethnicity, grade, recruitment site) and treatment characteristics (age at diagnosis, cancer diagnosis, treatment history, recurrence history) found to be significantly associated (p < .05) with perceived quality of care or patient engagement were included in the multiple linear regression models as control variables.

We built multiple linear regression models containing the same set of variables in order to assess the consistency of our results and the validity of our assumptions. First, we tested a multiple linear regression model using listwise deletion (a complete case analysis). The results of the regression diagnostics from this model suggested that our data violated the assumption of normally distributed residuals (Shapiro-Wilks test p-value < .001) and one participant’s response was influencing the model beyond what would be expected (dfit = 4.97). We removed the influential response and re-ran the complete case analysis. To address our normality violation, we analyzed a multiple linear regression model using robust regression and a second multiple linear regression model using bootstrapping. The results from the complete case analysis without the influential response, the robust regression, and the bootstrapped models yielded the same conclusions (results not shown). We also assessed multicollinearity in the complete case model without the influential point using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF was found to be satisfactory (Mean VIF = 1.52).

Our final analytic models, reported here, were assessed in a two-step process. First, we analyzed a multiple linear regression model that included significant demographic and treatment characteristics, cognitive development, transitional readiness, and patient engagement. Our second multiple linear regression model built upon the first one by adding the three dimensions of the patient-provider relationship (supporting independence, family-centered communication, and respectful relationships). We used multiple imputation using chained equations to account for the missing data in our sample. We performed twenty-five imputations with a small sample degrees of freedom adjustment after testing that our data appeared to be missing at random. We assessed the validity of our imputed models using traditional imputation diagnostics, including fraction of missing information (no value higher than 0.10) and relative efficiencies (all greater than 0.99), and found that our imputation models were robust. To assess the fit of our final model, we compared results from the complete case analysis to the imputed model and found the conclusions to be the same. The p-value was set at 0.05, all tests were two-sided, and analyses were conducted using Stata 14.2 (College Station, TX).

3. Results

Of the 103 participants, 2 surveys were eliminated and our final analytic sample included 101 adolescent cancer patients. One survey was eliminated due to missing data on more than 25% of the survey, and the second survey was eliminated due to its influential survey response (described in detail in statistical analysis section, above). The mean age at survey completion of the sample was 15.6 years (SD = 2.9), and the mean age at diagnosis was 13.8 years (SD = 3.1, Table 1). Most of the participants were white (60.4%), diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma (58.4%), and had no history of recurrence (81.2%). A little more than half were currently still receiving treatment for their cancer (56.4%), with most receiving chemotherapy (98.0%) and surgery (53.5%). Bi-variate tests found that receipt of chemotherapy (t(97) = 7.0, p < .001) was significantly associated with perceived quality of care, and age at diagnosis (r = 0.21, p = 0.04) was significantly associated with patient engagement.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (n=101)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Current Age (years), M (SD) | 15.6 (2.9) |

| Age at Diagnosis (years), M (SD) | 13.8 (3.1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 60 (59.4) |

| Female | 41 (40.6) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black or African American | 8 (7.9) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 26 (25.7) |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 61 (60.4) |

| Other | 6 (5.9) |

| Highest Grade in School Completed | |

| 5–7 | 20 (19.8) |

| 8–11 | 55 (54.5) |

| High School Graduate | 13 (12.9) |

| Some College Courses | 13 (12.9) |

| Primary Cancer Diagnosis | |

| Leukemia/Lymphoma | 59 (58.4) |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) Neoplasma | 5 (5.0) |

| Bone sarcomas | 21 (20.8) |

| Soft tissue and Kaposi sarcoma | 8 (7.9) |

| Germ Cell Cancer | 5 (5.0) |

| Other | 2 (2.0) |

| Treatment | |

| Chemotherapy | 99 (98.0) |

| Radiation | 42 (41.6) |

| Surgery | 54 (53.5) |

| Bone Marrow Transplant | 7 (6.9) |

| Other | 1 (1.0) |

| Treatment Status | |

| Active Treatment | 57 (56.4) |

| Completed Treatment | 44 (43.6) |

| Recurrence Status | |

| Recurrence | 19 (18.8) |

| No Recurrence | 82 (81.2) |

3.1. Patient Engagement and Perceived Quality of Care

Participants perceived high quality of care (M=14.9, SD=1.6) and reported moderate to high levels of patient engagement (M=16.2, SD=3.2). Patient engagement was not significantly associated with perceived quality of care among adolescent cancer patients in the model that only adjusted for cognitive development, transitional readiness, and demographic characteristics (b = .07, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: −0.03, 0.17) or in the final model that included all the above variables and the dimensions of the patient-provider relationship (Table 2; b = .02, 95% CI: −0.06, 0.11).

Table 2.

Regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the adolescents’ perceptions of their quality of care in the full model

| b (95% CI) | Standard Error | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Development | 0.04 (−0.01, 0.08) | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Transitional Readiness | 0.02 (−0.11, 0.15) | 0.07 | 0.78 |

| Patient Engagement | 0.02 (−0.06, 0.11) | 0.04 | 0.58 |

| Supporting Independence | 0.34 (0.17, 0.52) | 0.09 | < .001 |

| Family-Centered Communication | 0.04 (−0.09, 0.16) | 0.06 | 0.55 |

| Respectful Relationships | 0.18 (−0.13, 0.50) | 0.16 | 0.25 |

Note. Model adjusted for history of chemotherapy (yes/no) and age at diagnosis

Bolded results indicate a statistically significant relationship at the p < .05 level

R2 of complete case analysis = 0.42, p < .001

3.2. The Patient-Provider Relationship and Perceived Quality of Care

Overall, participants reported positive experiences with their healthcare providers, and endorsed that their providers supported their independence (M=22.4, SD=2.2), utilized family-centered communication (M=14.1, SD=2.4), and displayed respectful relationships (M=11.4, SD=1.1). In the final multiple linear regression model, we examined the association between the dimensions of the patient-provider relationship and perceived quality of care and found that experiencing increased independence support from providers (b = .34, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.52) was significantly associated with increased perceived quality of care.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Adolescent cancer patients inhabit a unique space within the cancer care community as they are more independent and cognitively prepared to play a role in their cancer care than their pediatric counterparts (patients diagnosed under the age of 10). Our cross-sectional, multi-site study found that adolescent cancer patients emphasize their healthcare provider’s support of their independence in perceiving high-quality cancer care, over and above patient engagement and other dimensions of the patient-provider relationship. This contrasts with the adult cancer literature that highlights the importance of patient engagement in improved quality of care [4,6–8]. Patient engagement prioritizes the patient’s role in shared-decision making and healthcare management, but adolescents are still developing important cognitive and psychosocial skills necessary to fully manage their diagnosis and treatment. Our findings highlight the necessity of considering engagement differently among adolescent cancer patients, and examining alternative mechanisms for the improvement of quality cancer care within this population.

A primary focus of the patient engagement literature, broadly, has been on the importance of shared decision-making [31]. It is believed that when patients have a role in medical decisions, they are more likely to understand their treatment plan, feel it aligns with their preferences, and are more likely to adhere to that treatment plan [32]. Most adolescent patients are under the age of 18 years, like pediatric patients, and cannot legally make their own medical decisions. However, research suggests that adolescents want to participate in treatment decision-making [21]. Additionally, they are often still developing important cognitive and emotional regulation skills necessary for medical decision-making [33,34]. It is perhaps expected, therefore, that we found no significant association between patient engagement and perceived quality of care in our study. Redefining patient engagement for cancer patients of differing developmental stages is necessary, and providing developmentally appropriate information [35,36], parents consistently including the adolescent in medical conversations [37], and checking in with the adolescent regularly regarding their participation preference [37] may be mechanisms to increase patient engagement.

A primary focus of adolescence is the development of autonomy and the ability to live independently [38]. For most adolescents, these skills develop through increasing school responsibilities, potentially starting part-time work, shifting parent-child relationships, and burgeoning romantic relationships [9]. A mistimed experience, like a cancer diagnosis, can interrupt this normal developmental trajectory [39]. Therefore, the newly formed patient-provider relationship becomes an important mechanism through which developmental milestones may still be achieved. Our study supports the necessity of scaffolding within the patient-provider relationship because adolescent patients perceived higher quality care when their providers were more likely to support their independence. Adolescent cancer patients recognize that they may not always want to make potentially life-threatening decisions on their own [22,23,36], but want involvement in as much of their treatment planning as possible [37].

4.2. Limitations

The findings from the current study should be interpreted considering its limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data precludes the ability to make any conclusions based on the causal effects of the significant relationships, and there is the possibility that the relationships are bi-directional. The use of in-person recruitment techniques led to a high participation rate among the current sample, lending credence to the generalizability of the study’s findings. However, the act of taking the survey in the environment they received their care may increase participants’ likelihood of reporting positive responses. Second, participants’ parents were usually in the exam room with them, and the survey instructions advised adolescents to ask their parent/guardian for help with the survey, if needed. The presence of parents/guardians or their help in completing the survey instrument may influence the likelihood of a positive response. We did not collect information on the presence of parents/guardians because our survey was anonymous, and we, therefore, cannot assess if parent presence affected adolescents’ responses. Third, we conducted our study in pediatric oncology clinics located in the United States. The definition of adolescent and their perceived importance of patient engagement and different dimensions of the patient-provider relationship may vary across different countries and cultures. Finally, the lack of tailored measurement may impact the study’s findings. Although the measures had satisfactory reliability, few measures were developed specifically for use with adolescent cancer patients, and several demonstrated ceiling effects in our sample. The participants in the study expressed that some of the items did not apply to their experience. There is a clear need for measures developed and validated within the adolescent cancer population to better examine these important constructs.

4.2. Conclusions

The findings of the current study highlight the need to consider adolescent cancer patients separate from their older and younger counterparts. Their perception of quality of care was driven, in large part, by the patient-provider relationship rather than engagement in their care. As cancer care providers continue to recognize the increased, autonomous role adolescents desire to play in their medical treatment, adolescents will become better prepared to transition into the adult healthcare context, feel more supported, and perceive higher quality care.

4.3. Practice Implications

Improving quality of care in adolescent oncology requires a restructuring of our approach to care with adolescent patients: they are not children nor are they adults. Care in this population requires a respect of their burgeoning cognitive and psychosocial skills while supporting their uncertainty and fear in the cancer care context. The current study worked with nursing staff to deliver the brief survey using an iPad/tablet during downtime within previously scheduled clinic appointments. This process did not interrupt the normal patient flow of the clinic, and would provide adolescents the opportunity to express their opinion, preferences for care involvement, and questions they may want to discuss. By utilizing this format, adolescents of different ages and developmental capabilities would be able to inform their providers on how best to interact with them. Previous research suggests that adolescent cancer patients feel involved and supported in their care if they are provided information and participate in treatment decisions, even if the ultimate decision is made by their parent or guardian [21]. Structuring adolescent cancer care in this way allows for adolescents to feel supported, but also provides healthcare providers the opportunity to tailor their behaviors to the developmental skills of their patients, which can vary widely across the adolescent developmental stage [9]. The current study supports the feasibility of using an iPad/tablet to collect feedback from adolescent patients on their experience and preferences, but future research will need to test the most appropriate format, content areas, and effectiveness of this type of data collection in improving patient engagement and quality of care.

Highlights.

Patient engagement is not associated with quality of care in adolescent oncology.

Providers supporting adolescents’ independence is associated with quality of care.

Adolescents place more emphasis on provider relationships than engagement.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the effort of Regan Pulaski and Mary Jane Galvin in helping with participant recruitment. Without their dedication to the needs of adolescent cancer patients, the current sample would not have been collected. We would also like to sincerely thank the adolescents who took the time to answer the survey questions.

Funding Source and Disclosure

This work was supported by the Mattoon-Kline Endowed Scholarship and the CLAS Dean’s Pre-Doctoral Fellowship at the University of Connecticut awarded to Dr. Siembida. Neither funding source played any role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Appendix

Factor loadings and communalities based on principle axis factoring with promax rotation for 13 items from a 14-item modified version of the Give Youth a Voice Questionnaire and the Measure of Processes of Care (N = 97)

| Item | Supporting Independence | Family-Centered Communication | Respectful Relationships | Communalitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s α | 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.66 | |

|

| ||||

| Feel you can trust them | 0.57 | 0.37 | ||

| Show they care about you and your family | 0.58 | 0.33 | ||

| Give you and your parent(s) written information about your treatment | 0.58 | 0.54 | ||

| Let you and your parent(s) choose when to receive information and what type of information you receive | 0.59 | 0.45 | ||

| Talk to you honestly | 0.80 | 0.66 | ||

| Fully explain treatment choices to you and your family | 0.78 | 0.66 | ||

| Trust you know yourself best | 0.47 | 0.55 | ||

| Give you a chance to talk | 0.77 | 0.72 | ||

| Treat you as an individual | 0.69 | 0.51 | ||

| You and your family have final say in treatment decisions | 0.66 | 0.43 | ||

| Look at all the needs of you and your family instead of just physical needs (for example, emotional and social needs) | 0.43 | 0.35 | ||

| Understand your feelings | 0.50 | 0.53 | ||

| Give you a chance to say what you want | 0.88 | 0.70 | ||

|

| ||||

| Proportion Variance Explained | 69.7% | 50.0% | 40.1% | |

Note. Factor loadings < 0.4 suppressed for clarity

Communality describes the relation between each item and all other items in the measure prior to rotation

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors confirm that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

I confirm that all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Author Contributions

Elizabeth Siembida made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study; data collection; data analysis and interpretation; drafting the manuscript; and has provided approval of the final manuscript. Nina Kadan-Lottick made substantial contributions to the design of the study; data collection; drafting the manuscript; and has provided approval of the final manuscript. Kerry Moss made substantial contribution to the conception and design of the study; data collection; drafting the manuscript; and has provided approval of the final manuscript. Keith Bellizzi made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study; data analysis and interpretation; drafting the manuscript; and has provided approval of the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. Closing the gap: research and cancer care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance; 2006. [accessed 29 September 2017]. (NIH Publication No. 06-6067) https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya/research/ayao-august-2006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stinson JN, Sung L, Gupta A, White ME, Jibb LA, Dettmer E, Baker N. Disease self-management needs of adolescents with cancer: Perspectives of adolescents with cancer and their parents and healthcare providers. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:278–86. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society of Clinical Oncology, The state of cancer care in America. 2014: A report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:119–43. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health Policy Brief: Patient Engagement. Health Aff. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27:520–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1931-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: Better health outcomes and care experiences; Fewer data on costs. Health Aff. 2013;32:207–14. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, Tusler M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1443–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNeely C, Blanchard J. The Teen Years Explained: A Guide to Healthy Adolescent Development. Baltimore, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonnie RJ, Scott ES. The teenage brain: Adolescent brain research and the law. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22:158–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keating DP. Cognitive and brain development in adolescence. Neuropsychiatr Enfance Adolesc. 2012;64:267–79. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overton WF. Competence and procedures: Constraints on the development of logical reasoning. In: Overton WF, editor. Reasoning, Necessity, and Logic: Developmental Perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; Hillsday, NJ: 1990. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–63. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg L. Should the science of adolescent brain development inform public policy. Am Psychol. 2009;64:739–50. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.64.8.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benish-Weisman M, Levy S, Knafo A. Parents differentiate between their personal values and their socialization values: The role of adolescents’ values. J Res Adolesc. 2013;23:614–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grotevant HD, Cooper CR. Individuality and connectedness in adolescent development: Review and prospects for research on identity, relationships, and context. In: Skoe EEA, von der Lippe AL, editors. Personality Development in Adolesence: A Cross National and Life Span Perspective. Taylor & Frances/Routledge; Florence, KY: pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kagitcibasi C. Adolescent autonomy-relatedness and the family in cultural context: What is optimal. J Res Adolesc. 2013;23:223–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamis-LeMonda CS, Way N, Hughes D, Yoshikawa H, Kalman RK, Niwa EY. Parents’ goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Soc Dev. 2007;17:183–09. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chambers RA, Taylor JR, Potenza MN. Developmental neurocircuity of motivation in adolescence: A critical period of additional vulnerability. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1041–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eluvathingal TJ, Hasan KM, Kramer L, Fletcher JM, Ewing-Cobbs L. Quantitative diffusion tensor tractography of association and projection fibers in normally developing children and adolescents. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:2760–8. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siembida EJ, Bellizzi KM. The doctor-patient relationship in the adolescent cancer setting: A developmentally-focused literature review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2015;4:108–17. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2015.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinds PS, Drew D, Oakes LL, Fouladi M, Spunt SL, Church C, Furman WL. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9146–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwaanswijk M, Tates K, van Dulmen S, Hoogerbrugge PM, Kamps WA, Bensing JM. Young patients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences in paediatric oncology: Results of online focus groups. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:35–44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zwaanswijk M, Tates K, van Dulmen S, Hoogerbrugge PM, Kamps WA, Beishuizen A, Bensing JM. Communicating with child patients in pediatric oncology consultations: A vignette study on child patients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences. Psychooncology. 2011;20:269–77. doi: 10.1002/pon.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.JAYAO. What should the age range be for AYA oncology. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1:3–10. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2011.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sebastian RA, Ramos MM, Stumbo S, McGrath J, Fairbrother G. Measuring youth health engagement: Development of the youth engagement with health services survey. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:334–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Sinha R, Shahbaz A, Klaassan R, Dix D. Is the Give Youth a Voice questionnaire an appropriate measure of teen-centred care in paediatric oncology: A Rasch measurement theory analysis. Health Expect Epub. 2013 doi: 10.1111/hex.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klassen AF, Dix D, Cano SJ, Papsdorf M, Sung L, Klaassen RJ. Evaluating family-centred service in paediatric oncology with the measure of processes of care (MPOC-20) Child Care Health Dev. 2008;35:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beckert TE. Cognitive autonomy and self-evaluation in adolescence: A conceptual investigation and instrument development. N Am J Psychol. 2007;9:579–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawicki GS, Whitworth R, Gunn L, Butterfield R, Lukens-Bull K, Wood D. Receipt of health care transition counseling in the national survey of adult transition and health. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e521–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hibbard JH. Patient activation and the use of information and support informed health decisions. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hibbard JH, Mahoney E, Sonet E. Does patient activation level affect the cancer patient journey. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:1276–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Woolard J, Graham S, Banich M. Reconciling the complexity of human development with the reality of legal policy: Reply to Fischer, Stein, and Heikkinen. Am Psychol. 2009;64:601–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3, Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 1003–67. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coyne I, Amory A, Kiernan G, Gibson F. Children’s participation in shared decision-making: Children, adolescents, parents, and healthcare professionals’ perspectives and experiences. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young AJ, Kim L, Baker JN, Schmidt M, Camp JW, Barfield RC. Agency and communication challenges in discussions of informed consent in pediatric cancer research. Qual Health Res. 2010;20:628–43. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weaver MS, Baker JN, Gattuso JS, Gibson DV, Sykes AD, Hinds PS. Adolescents’ preferences for treatment decisional involvement during their cancer. Cancer. 2015;121:4416–24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger KS. The Developing Person: Through the Life Span. New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bellizzi KM, Smith A, Schmidt S, Keegan THM, Zebrack B, Lynch CF, Deapen D, Shnorhavorian M, Tompkins BJ, Simon M. Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer. 2012;118:5155–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]