Abstract

Interaction of TLR9 with ligands activates nuclear factor-κB, leading to proinflammatory cytokine production. Excessive TLR activation is a pathogenic factor for inflammatory diseases. This study has examined cell-permeating decoy peptides (CPDPs) derived from the TLR9 Toll-IL-1R Resistance (TIR) domain. CPDP 9R34, which included AB loop, β-strand B, and N-terminal BB loop residues, inhibited TLR9 signaling most potently. CPDPs derived from α-helices C, D, and E, i.e., 9R6, 9R9, and 9R11, also inhibited TLR9-induced cytokines, but were less potent than 9R34. 9R34 did not inhibit TLR2/1, TLR4, or TLR7 signaling. The N-terminal deletion modification of 9R34, 9R34-ΔN, inhibited TLR9 as potently as the full length 9R34. Binding of 9R34-ΔN to TIR domains was studied using cell-based Förster Resonance Energy Transfer/Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging approach. Cy3-labeled 9R34-ΔN dose-dependently decreased fluorescence lifetime of TLR9 TIR-Cerulean (Cer) fusion protein. Cy3-9R34-ΔN also bound TIRAP TIR, albeit with a lesser affinity, but not MyD88 TIR; whereas CPDP from the opposite TIR surface, 9R11, bound both adapters and TLR9. Intraperitoneal administration of 9R34-ΔN suppressed ODN-induced systemic cytokines and lethality in mice. This study identifies a potent, TLR9-specific CPDP that targets both receptor dimerization and adapter recruitment. Location of TIR segments that represent inhibitory CPDPs suggests that TIR domains of TLRs and TLR adapters interact through structurally homologous surfaces within primary receptor complex, leading to formation of a double-stranded, filamentous structure. In the presence of TIRAP and MyD88, primary complex can elongate bidirectionally, from two opposite ends; whereas in TIRAP-deficient cells, elongation is unidirectional, only through the αE side.

Keywords: macrophages, cytokines, TLR9, TIR domain, cell-permeating decoy peptides, FRET-FLIM

INTRODUCTION

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), a family of pattern recognition receptors (PRR), are evolutionarily conserved and present in most animal phyla. TLRs function as a component of the innate immune system responsible for recognition of various microbial molecules (1, 2). These receptors play an important role in the initiation and maintenance of inflammatory response to pathogens. Excessive or prolonged TLR signaling is a pathogenic factor in many inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (1, 3–8). Toll-like receptors have different cellular localization. TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR6 are located at the plasma membrane. These TLRs recognize microbial lipids, lipopeptides, and proteins. TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, and TLR13 are localized in intracellular compartments and recognize nucleic acids, whereas TLR11 and TLR12, also endosomally expressed, recognize bacterial proteins (9–11). Agonists of TLR10 remain unknown (12). TLR9 is activated by DNA sequences that contain unmethylated CpG motifs, often present in bacterial and viral DNA (1, 6, 13, 14).

TLRs are type I transmembrane receptors that initiate intracellular signaling through Toll/Interleukin-1R homology domains (TIR). Activated TLRs dimerize and bring their TIR domains to direct physical contact (15). The formed TIR dimers recruit TIR domain-containing adapter proteins through TIR-TIR interactions (16–18). There are four TIR-containing TLR adapter proteins that are involved in signaling, i.e., MyD88, TIRAP/Mal, TRIF, and TRAM (5, 19, 20). Recruitment of MyD88 to TLRs promotes the assembly of MyDDosome, the signaling complex formed by death domains of MyD88, IRAK4, and IRAK2 (21, 22). MyDDosome formation activates IRAKs, leading to the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) (19, 22, 23). TLR4 and TLR3 can also engage TRIF, leading to formation of Triffosome and activation of interferon-regulatory factor-3 (IRF-3) (20, 24, 25). TIRAP and TRAM, often referred to as bridging adapters, stabilize TLR TIR dimers and facilitate the recruitment of MyD88 and TRIF, respectively (26–29).

TIRs are α/β protein domains, the core of which is formed by the central, typically 5-stranded, parallel β-sheet, surrounded by 5 α-helices (30–32). Sequence similarity of TIR domains is typically limited to only 20 – 30% (29, 33, 34). TIR domains can interact through structurally diverse regions (18, 35–39). For instance, TLR2 TIR α-helix D interacts with TIRAP, whereas its AB loop is involved in receptor dimerization (37).

Involvement of TLRs in development of rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis suggests a significant potential of TLR antagonists in treatment of inflammatory diseases (6, 40–50). Our previous studies screened libraries of cell-permeating decoy peptides (CPDP) derived from TIR domains of TLR2, TLR4, their adapters and co-receptors. The CPDPs tested in this and our previous studies are comprised of two functional parts. The common, N-terminal part of a CPDP is the cell-permeating peptide vector derived from Antennapedia homeodomain (RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK) (51). Many studies, including our previous CPDP screenings, have demonstrated the efficacy of this vector for intracellular delivery of cargoes of diverse size and chemical nature in cell culture and small animal models (37, 52–56). The C-terminal half of a CPDP is a segment of TIR domain primary sequence that represents a particular, non-fragmented patch of TIR domain surface that might serve as a TIR-TIR interface. The TIR libraries were designed in such a way that all peptides in a library collectively represent the entire surface of the TIR. Screenings of TIR peptide libraries have resulted in identification of several TLR inhibitors that have distinct specificities and dissimilar sequences (18, 37, 38, 53, 55, 57). The anti-inflammatory properties of several peptides that resulted from these studies have been confirmed by several independent groups (58–60). Thus, Hu et al. observed a potent anti-inflammatory effect of the TIRAP-derived peptide TR6 (53) in a mouse model of LPS-induced mastitis (58). Same research group demonstrated the protective action of TRAM-derived peptide TM6 (55) in LPS-induced acute lung injury (59). TLR4-derived peptide 4BB (36) decreased effects of LPS on calcium fluxes and neuronal excitability in studies conducted by Allette et al. (60). Although several independent research groups have reported analogous TLR inhibitory peptides from bacterial and viral proteins (61–63), no inhibitor that targets TLR9 has been reported to date.

The present study identifies new CPDP inhibitors of TLR9. The most potent inhibitory peptide of the TLR9 TIR library, 9R34, and its modification, 9R34-ΔN, are derived from the surface-exposed segment of TLR9 TIR that includes AB loop, β-strand B, and N-terminal residues of BB loop. Peptides from α-helices E, D, and to a lesser extent, C (i.e., 9R11, 9R9, and 9R6) also inhibited TLR9, but were less potent. Using a cell-based binding assay, we demonstrated that 9R34-ΔN binds the TLR9 TIR domain and, with a slightly lower affinity, TIRAP TIR. 9R34-ΔN inhibited systemic cytokine activation induced in mice by ODN 1668 and protected D-galactosamine (D-Gal) pretreated mice against TLR9-induced lethality. The results presented identify novel TLR9 inhibitors and provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of TLR9 signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and cells

Eight week old female C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were isolated and cultivated according to Weischenfeldt and Porse (64). Mouse tibias and femurs were flushed with the ice-cold PBS and the cells obtained transferred to RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% L929 cell supernatant. The cells were cultured for 10–14 days prior to experiments.

TLR agonists

ODN 1668, S-(2,3-bis (palmitoyloxy)-(2R, 2S)-propyl)-N-palmitoyl-(R)-Cys-Ser-Lys4-OH (Pam3C), and R848 were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). Phenol purified, Escherichia coli K235 LPS (65) was a kind gift of Dr. Stefanie N. Vogel (UMB SOM).

Peptide design, synthesis, and reconstitution

Decoy peptides from TLR9 TIR domain were synthesized in tandem with the cell-permeating Antennapedia homeodomain sequence (RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK) (51), placed at the N-terminus, as in our prior studies that have demonstrated that this vector is effective for intracellular delivery of inhibitory decoy sequences in vitro and in vivo (18, 37, 38, 53, 55, 57). Peptide sequences are shown in Table I. CPDP were synthesized by Aapptec (Louisville, KY) or GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). The Cy3-labeled peptides were produced by CPC Scientific Inc., (Sunnyvale, CA) and Lifetein (Franklin Township, NJ). The Cy3 label was placed at the peptide N-terminus. The purity of all CPDP was ≥95%. Concentrations of reconstituted peptides were determined spectrophotometrically (66).

Table I.

Sequences of TLR9 TIR-derived decoy peptides

| Peptide | Sequence | Predominant structural region |

|---|---|---|

| 9R1 | GRQSGRDEDALPYD | N-terminal segment |

| 9R2 | DKTQSAVADWVYNE | AA loop, α-helix A1 |

| 9R3 | RGQLEECRGRWALR | α-helix A, AB loop |

| 9R34 | GRWALRLCLEERD | AB loop, β-strand B, N-terminal residues of BB loop |

| 9R34-ΔN | ALRLCLEERD | AB loop, β-strand B, BB loop |

| 9R34-ΔC | GRWALRLCLE | AB loop, β-strand B |

| 9R34-C/S | GRWALRLSLEERD | AB loop, β-strand B, BB loop |

| 9R34-ΔL1 | GRWALRACLEERD | AB loop, β-strand B, BB loop |

| 9R34-ΔL2 | GRWALRACAEERD | AB loop, β-strand B, BB loop |

| 9R4 | LEERDWLPGKTLFE | β-strand B, BB loop, α-helix B |

| 9R5 | NLWASVYGSRKT | α-helix B, BC loop, β-strand C |

| 9R6 | HTDRVSGLLRASFL | α-helix C |

| 9R7 | LAQQRLLEDRKD | α-helix C, CD loop, β-strand D |

| 9R8 | SPDGRRSRYVR | DD loop, α-helix D |

| 9R9 | RYVRLRQRLCRQS | α-helix D, DE loop |

| 9R10 | QSVLLWPHQPSGQ | DE loop, β-strand E, EE loop |

| 9R11 | RSFWAQLGMALTRD | α-helix E |

| 9R12 | NHHFYNRNFCQGPT | C-terminal segment |

Secondary structure elements of the TIR domain are consecutively indicated by letters, with letter ‘A’ indicating the most N-terminal element.

Evaluation of cytokine expression by quantitative real time PCR

Two × 106 BMDMs per well were plated in 12-well plates, incubated overnight, and treated with CPDP for 30 min prior to stimulation with a TLR agonist for 1 hour. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA isolated using Trizol (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) and reverse transcribed using RevertAid RT Reverse Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The cDNA obtained was amplified with gene-specific primers for mouse HPRT, TNFα, IL-1β, IL-12p40, or IL-6 and Fast SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described (53).

ELISA evaluation of cytokine secretion

One × 106 BMDMs per well were plated in 24-well plates and treated with CPDP for 30 min prior to stimulation with a TLR agonist for 5 hours. Mouse TNF-α and IL-12p40 concentrations were measured in supernatants using ELISA kits from Biolegend, Inc (San Diego, CA).

Immunoprecipitation of MyD88-containing signaling complexes and immunoblotting

Four × 106 BMDM per well were plated in 6-well plates and treated with CPDP for 30 min prior to stimulation with ODN 1668 for 90 min. Cells were lysed in 600 μL of buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Cell extracts were incubated overnight with 1 μg of anti-mouse MyD88 antibody (AF3109) (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN), followed by 4 h incubation with 20 μl protein G Sepharose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The beads were then washed 3 times with 500 μL of lysis buffer and boiled in 60 μL of Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). Cell extracts were electrophoresed on 10% acrylamide gel by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). Rabbit anti-MyD88 IgG was purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Mouse anti-IRAK4 IgG was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies against mouse and rabbit IgG were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). The stabilized substrate for alkaline phosphatase was from Promega (Madison, WI).

Expression vectors

MyD88-Cer, TIRAP-Cer, and TLR2-Cer expression vectors were described previously (37, 55). Because of low expression level, full-length TLR4-Cer and TLR9-Cer vectors were replaced with TLR4 TIR-Cer and TLR9 TIR-Cer, respectively. These vectors do not include TLR4 and TLR9 ectodomains but encode full transmembrane sections and TIR domains (37).

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM)

Three × 106 HeLa cells were transfected with 10 μg of MyD88-Cer, TIRAP-Cer, TRAM-Cer, TLR2-Cer, TLR4 TIR-Cer, or TLR9 TIR-Cer expression vectors using a Lipofectamine 3000 kit from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) per manufacturer recommendations. Twenty four hours later, the transfected cells were trypsinized and reseeded into a 50-well gasket (Grace Bio-Labs; Bend, OR) mounted on a microscope slide at the density 8000 cells/well. Next day, cells were treated with Cy3-9R34-ΔN or Cy3-9R11 for 1 h and fixed on the slides with 4% paraformaldehyde solution.

Fluorescence lifetime images were acquired using the Alba V FLIM system (ISS Inc., Champagne, IL). The excitation was from the laser diode 443 nm coupled with scanning module (ISS) through multiband dichroic filter 443/532/635 nm (Semrock) to Olympus IX71S microscope with objective 20 × 0.45 NA (UPlan Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Emission was observed through bandpass filter 480/30 nm (Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT) and detected by a photomultiplier H7422-40 (Hamamatsu). Measurements were performed using frequency domain (FD) and time domain (TD) modalities of the FLIM system. FD FLIM data were acquired using ISS A320 FastFLIM electronics with n harmonics of 20 MHz laser repetition frequency (n = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). FastFLIM was calibrated using fluorescein in buffer pH 8.0 as a standard with a single lifetime of 4.0 ns. TD FLIM images were acquired using time-correlated single photon counting TCSPC Model SPC-830 (Becker & Hickl, Germany). Images (256 × 256 pixels) were acquired with resolution varied in the range ~0.4 – 0.7 μm/pixel, using scan speed 1 ms/pixel. To avoid pixel intensity saturation in bright cells and to improve the signal from dim cells, two to five overlapping scans were used for acquisition of FLIM images. Image sizes varied from 100 × 100 to 180×180 μm to accommodate multiple cells. FLIM data were analyzed with VistaVision Suite software (Vista v.212 from ISS). Fluorescence lifetime was determined using single- and bi-exponential intensity decay models. Average lifetime images were generated based on pixel-by-pixel analysis using the combined signal of two neighboring pixels in all directions (bin 2 = 25 pixels). The binning was used to improve the signal for analysis. The average lifetimes were calculated from fitted parameters, decay times τi and amplitudes αi, τa = Σαiτi. The bi-exponential fitting procedure was performed with one-lifetime component fixed at 3.1 ns, which was found common for most images. To calculate the effective FRET efficiency (E), average lifetimes of the donor only images (τD ) and donor-acceptor images (τDA ) were used, E = 1 – τDA/τD . It should be noted that non-quenched donor molecules also contribute to the value of τDA, more significantly at low acceptor concentrations as was discussed previously (67).

Animal experiments

Systemic cytokine levels were measured in plasma samples obtained 1, 3, and 5 hours after intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of 7.86 nmol of ODN 1668 or 67 nmol of Pam3C per mouse, using ELISA kits from Biolegend Inc. (San Diego, CA). CPDP were dissolved in PBS and administered i.p. at the dose of 200 nmol per mouse 1 hour before administration of a TLR agonist (37). For survival experiments, mice were sensitized to TLR9 agonists by i.p. injection of 20 mg of D-Gal 30 minutes before administration of peptides or PBS. ODN 1668 was used at the doses of 3.93 or 7.86 nmol/mouse 1.5 hours after D-Gal. Animal survival was monitored for 50 hours. All agents were administered i.p. in 500 μL volume of PBS. Animals had free access to food and water during the observation period. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals under a protocol that was approved by the UMB IACUC.

TLR9 TIR domain modeling

Template search was performed using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool), HMM-HMM – based lightningfast iterative sequence search (HHBlits) and the SWISS-MODEL template library (SMTL) (68, 69). The target sequence was searched with BLAST against the primary amino acid sequence contained in SMTL (68). An initial HHblits profile has been built using the procedure outlined in (69), followed by 1 iteration of HHblits against NR20. The model was built based on the target-template alignment using ProMod3 (70). All images were produced using the UCSF Chimera viewer (71).

Data representation

Numerical data were statistically analyzed by the one way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

RESULTS

Identification of TLR9 inhibitory peptides

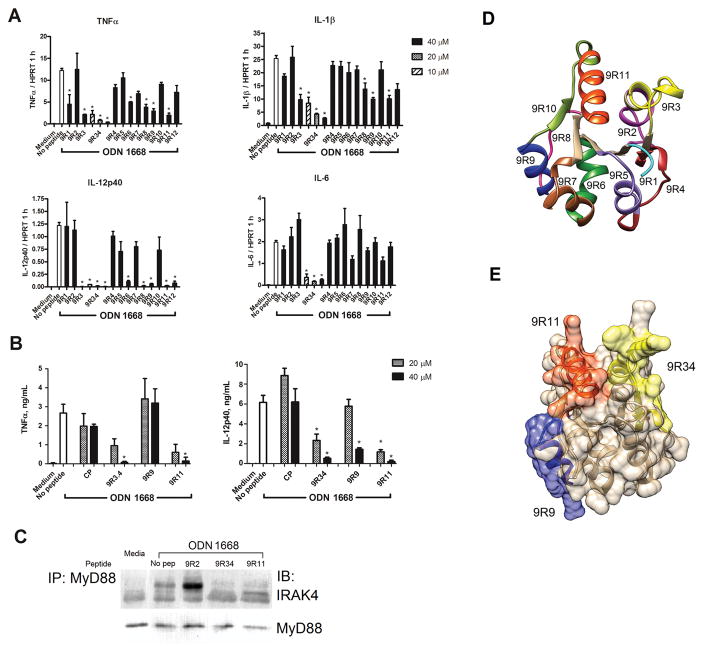

TLR9 peptide library was designed similarly to the libraries used in our previous studies of TLR-derived peptides (18, 37, 38). Each peptide in the library corresponds to a short segment of TLR sequence that presumably forms a non-fragmented patch of TIR surface. All peptides of the library together encompass the entire surface of TLR9 TIR. TLR9 sequence fragments were synthesized in tandem with the cell-permeating, 16 amino acid-long fragment of Antennapedia homeodomain positioned N-terminally (51). Sequences of TLR9 TIR peptides are presented in Table 1. CPDP were first evaluated at 40 μM based on their effect on cytokine expression in BMDM stimulated with ODN 1668 for 1 hour. Peptides 9R3, 9R34, 9R9, and 9R11 significantly suppressed TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12p40 mRNA expression measured 1 hour after stimulation, whereas effect on IL-6 mRNA expression was statistically significant only for 9R34 (Fig. 1A). Peptides 9R6 and 9R8 also demonstrated some inhibitory activity, but were overall less potent. Peptides 9R3 and 9R34 have overlapping sequences (Table 1). 9R34 inhibited expression of all tested cytokines when used at lower concentrations of 10 or 20 μM (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Effects of TLR9-derived CPDP on ODN 1668-induced cytokine expression and secretion. Mouse BMDMs were incubated in the presence of a 10, 20 or 40 μM decoy peptide for 30 min prior to stimulation with ODN 1668 (1 μM). (A) Cytokine mRNA expression measured 1 h after ODN 1668 challenge and normalized to the expression of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT). Data represent the means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. The statistical significance of changes in cytokine mRNA was determined by a one-way ANOVA test; *p < 0.001. (B) Cytokine concentrations in supernatants were evaluated by ELISA 5 h after cell stimulation. Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments. The statistical significance of changes in cytokine levels was determined by the one-way ANOVA test; *p < 0.01. (C) BMDM were lysed 3 h after cell treatment with ODN 1668 and lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-MyD88 Ab and immune complexes assessed with anti-IRAK4 Ab. (D) Segments of TIR domains represented by CPDPs. (E) Positions of inhibitory peptides 9R34, 9R9, and 9R11.

Three most potent inhibitory peptides identified in mRNA screens, 9R34, 9R9, and 9R11, were examined further based on their effect on cytokine secretion assessed in 5 hour supernatants of ODN-stimulated BMDM (Fig. 1B). CPDPs 9R34, 9R9, and 9R11 reduced secretion of IL-12p40 when used at 40 μM. CPDPs 9R34 and 9R11 were also effective at 20 μM. Both peptides also decreased the production of TNF-α, when used at 40 μM. CPDP 9R9 did not inhibit significantly the secretion of TNF-α (Fig. 1B). Apparent discrepancy between effects of 9R9 on TNF-α expression (Fig. 1A) and secretion (Fig. 1B) might be due to a weaker inhibitory potency of this peptide and the transitory nature of TNF-α mRNA expression (Fig. S1). Thus, the absence of 9R9 effects on TNF-α contents in 5 hour supernatants indicates that the initial reduction of mRNA expression observed in 1 hour samples (Fig. 1A) is compensated by elevated expression at the later time points (Fig. S1). Based on these results, CPDPs 9R34 and 9R11 were selected for further evaluation.

To exclude the possibility that the reduction in cytokine expression caused by peptides is due to general toxicity of inhibitory CPDPs we conducted the MTT cell viability assay. Inhibitory CPDP did not affect BMDM viability in a measurable way with or without concurrent TLR9 stimulation in all experimental conditions tested (Fig. S2).

TLR stimulation causes formation of MyDDosome, a signaling complex composed through interactions of IRAK and MyD88 death domains (21, 22). To test if peptides inhibit MyDDosome formation, MyD88 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of ODN-stimulated BMDM and the precipitates analyzed for IRAK4 presence (72). Pretreatment of BMDMs with CPDPs 9R34 or 9R11, but not with control peptide 9R2, prevented ODN 1668-induced MyDDosome formation (Fig. 1C).

Specificity of signaling inhibition by TLR9-derived peptides

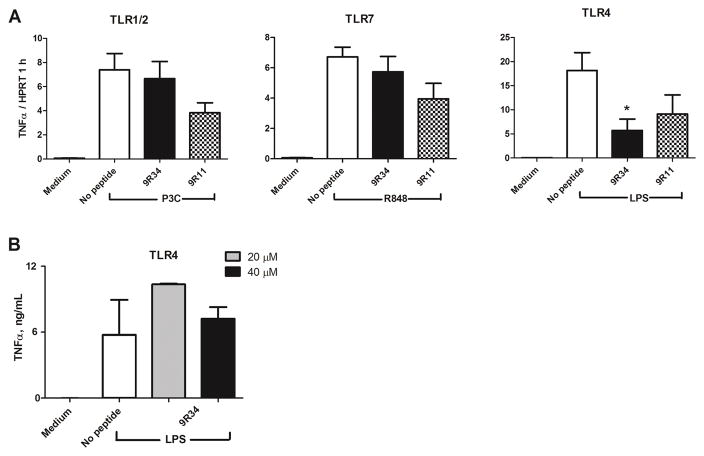

CPDPs 9R34 and 9R11 were examined for inhibition of TLR1/2, TLR4, and TLR7 signaling. BMDMs were stimulated with Pam3C, E. coli LPS, or R848 and TNF-α mRNA measured 1 hour after stimulation. TLR9 inhibitory peptides did not inhibit signaling induced by TLR1/2 or TLR7 agonist. Peptide treatment reduced the TNFα mRNA expression in LPS-stimulated cells by ~50 – 70% (Fig 2). This level of inhibition of the LPS-stimulated expression was significantly less than that of the ODN-stimulated expression, in which case more than 99% of expression was inhibited (Fig. 1A). Accordingly, 9R34 did not reduce the LPS-induced TNF-α secretion measured in 5 h BMDM supernatants (Fig 2B), suggesting that the 9R34 effects on the LPS-induced TNF-α mRNA is transient.

Figure 2.

Specificity of TLR inhibition by TLR9-derived CPDP. (A) BMDM were treated with 40 μM of indicated peptides for 30 min prior to stimulation with ODN 1668 (1 μM), E.coli LPS (0.1 μg/mL), R848 (2.85 μM), or P3C (0.33 μM). TNFα mRNA expression was measured 1 h after ODN 1668 challenge and normalized to the expression of HPRT. Data show means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. The statistical significance of changes was determined by a one-way ANOVA test; *p < 0.01. (B) BMDM were treated with 20 or 40 μM of 9R34 for 30 min prior to stimulation with E.coli LPS (0.1 μg/mL). TNFα concentration in supernatants was evaluated by ELISA 5 h after cell stimulation. Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Inhibitory properties of modified 9R34 peptides

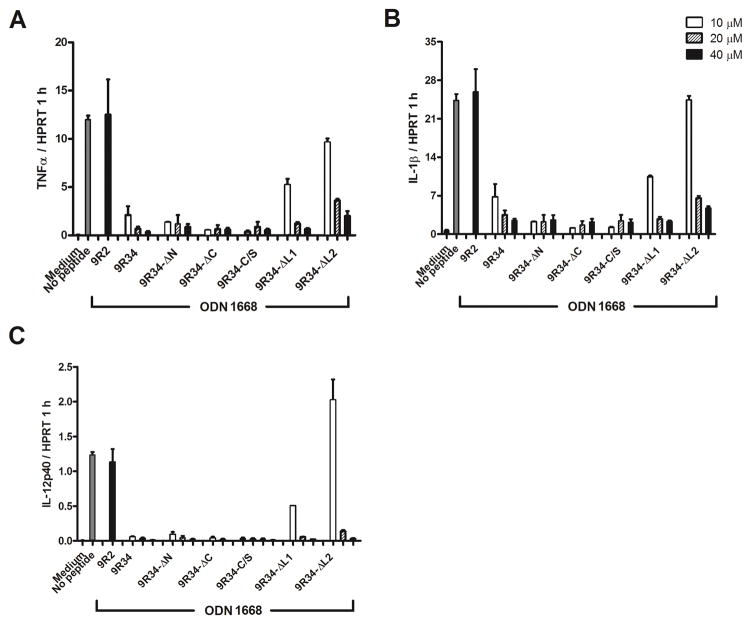

The experiments described above suggested that 9R34 is the most potent inhibitor from the peptides screened (Fig. 1). We noted, however, that millimolar stock solutions of this peptide were unstable; the peptide solutions were also unstable in the presence of high protein concentrations. Therefore, several modifications of 9R34 were generated to determine more precisely the epitopes responsible for signaling inhibition and to improve peptide solubility. The inhibitory potency of modified peptides was compared with that of the parent peptide. Five modifications of 9R34 were tested. Two modifications, 9R34-ΔN and 9R34-ΔC, are 9R34 deletion variants that were shortened by three amino acids at either N or C terminus. Three other modifications contained single amino acid replacements. 9R34-C/S had cysteine substituted for serine. 9R34-ΔL1 and 9R34-ΔL2 had one or two middle sequence leucines replaced by alanines (Table I). The results suggested that 9R34-ΔN, 9R34-ΔC and 9R34C/S were as potent as the parent peptide, whereas 9R34-ΔL1 and 9R34-ΔL2 inhibited TLR9 signaling less potently (Fig. 3). The 9R34-ΔN stock solutions were stable at concentrations up to 10 mM. This peptide remained soluble in bovine serum at high micromolar concentrations. These observations show that 9R34 inhibits TLR9 signaling sequence-specifically and suggest that 9R34-ΔN is better suited for in vivo applications.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of TLR9 signaling by 9R34 analogues. Mouse BMDMs were incubated in the presence of a 10, 20 or 40 μM decoy peptide for 30 min prior to stimulation with ODN 1668 (1 μM). Cytokine mRNA expression was measured 1 h after ODN 1668 challenge and normalized to the expression of HPRT. CPDP sequences are shown in Table 1. Data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments.

Selectivity of TIR binding by TLR9-derived CPDPs

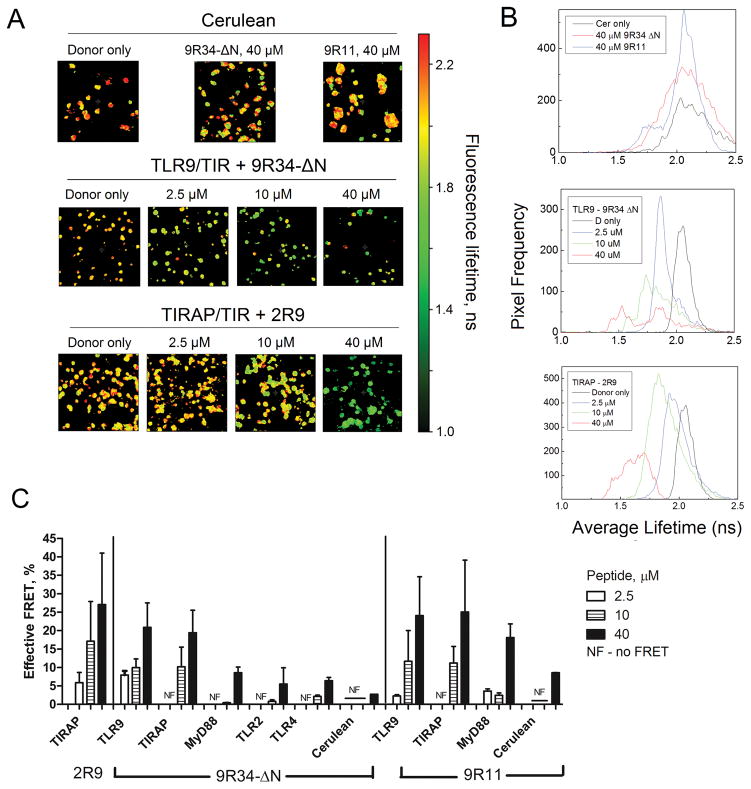

To identify potential binding partners of inhibitory peptides we used FRET approach coupled with Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) (18, 37, 67). HeLa cells were transiently transfected with an expression vector that encodes a TIR domain fused with Cerulean fluorescent protein (Cer). Cells were treated with various concentrations of a Cy3-labeled inhibitory peptide 48 hours after transfection (18). Cy3 is a suitable FRET acceptor for Cer fluorescence. A direct molecular interaction of a Cy3-labeled peptide with Cer-fused TIR domain should quench Cer fluorescence, leading to a decreased fluorescence lifetime. TLR9, MyD88, and TIRAP were selected as potential primary binding partners for Cy3-9R34-ΔN and Cy3-9R11. Cer-fused TLR2 and TLR4 TIR domains, and Cer not fused to a TIR, were used as controls. We previously demonstrated that the TLR2-derived peptide 2R9 binds TIRAP TIR (37). Therefore, the TIRAP-Cer with Cy3-2R9 was used as a positive binding control. Figure 4A shows FLIM images of HeLa cells transfected with different Cer-TIR constructs and treated with inhibitory peptides at various concentrations. The images show the average fluorescence lifetime of Cer component calculated on the pixel-by-pixel basis using the bi-exponential model with one component having a fixed lifetime (67). Histograms of panel 4B demonstrate the distribution of average fluorescence lifetime in corresponding images of panel A. A progressive shift of average fluorescence lifetime towards lower values observed with increasing peptide concentrations indicates the binding between donor and acceptor moieties. A larger decrease in average lifetime corresponds to a larger number of donor-acceptor pairs present within the sample, indicating an effective FRET (Fig. 4C). FRET efficiencies presented in panel C were calculated from the average lifetimes corresponding to entire images that contained multiple cells as in images shown in Fig. 4A, using data obtained in three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Effect of Cy3-labeled CPDPs on Cer fluorescence lifetime. (A) FLIM images of HeLa cells expressing Cer not fused with a TIR domain (upper row), or fused with TLR9 TIR or TIRAP-Cer (middle and bottom rows) and treated with a Cy3-labeled decoy peptide for 1 h. FLIM images show the average fluorescence lifetime of Cer component. (B) Histograms show frequencies of occurrence of particular average lifetimes in images shown in panel A. (C) FRET efficiency for different TIR-peptide pairs. Data represent means ± SEM of two independent experiments.

The strongest peptide-induced quenching was detected for the TLR9 TIR-Cer-expressing cells treated with Cy3-9R34-ΔN. This peptide quenched the TLR9 TIR-Cer fluorescence dose-dependently with FRET efficiency varying in the range of 9 – 23% (Fig. 4C). Fluorescence lifetime of TLR9 TIR-Cer construct was decreased even in cells treated with the minimal peptide concentration used (2.5 μM) (Fig. 4A, B, and C). Cy3-9R34-ΔN also notably quenched the fluorescence of cells that expressed the TIRAP-Cer (Fig. 4C). The Cy3-9R34-ΔN effect on TIRAP-Cer fluorescence was weaker than on that of the TLR9 TIR-Cer, as suggested by the absence of the effect of the lowest peptide concentration (Fig. 4C). The quenching observed for the control TIR-peptide pair, TIRAP – 2R9, was slightly higher than for the TLR9 – 9R34-ΔN pair (Fig. 4A, B, and C). The average fluorescence lifetime of Cer-labeled MyD88 TIR was not affected by Cy3-9R34-ΔN at lower peptide concentrations (2.5 and 10 μM) (Fig. 4C). The quenching of MyD88 TIR-Cer was notable at 40 μM peptide concentration, but considerably less in comparison with the effect on TLR9 and TIRAP TIR-Cer (Fig. 4C). Cy3-9R34-ΔN at 40 μM also slightly affected the fluorescence lifetime of control TLR2 TIR-Cer, TLR4 TIR-Cer, TRAM-Cer, and Cer not fused to a TIR domain (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S3). The effects on these constructs show the level of unspecific quenching of Cer by Cy3-labeled peptides at high peptide concentrations.

Cy3-9R11 dose-dependently quenched the fluorescence of TLR9 TIR-Cer with FRET efficiency varying in the range of 3 – 27% (Fig. 4C). In addition, Cy3-9R11 induced FRET from TIRAP-Cer, but only when used at higher concentrations of 10 or 40 μM (Fig. 4C). The quenching of MyD88-Cer fluorescence lifetime by Cy3-9R11 was also detectable, but less effective (Fig. 4C). Unspecific Cer quenching by Cy3-9R11 was observed at a peptide concentration of 40 μM, similarly to the effects of Cy3-9R34-ΔN (Fig. 4A, B and C).

In summary, the FLIM experiments suggest that both 9R34-ΔN and 9R11 bind TLR9 and TIRAP TIR. 9R11 also interacted with the MyD88 TIR, but with a lower affinity, whereas 9R34-ΔN did not interact with MyD88.

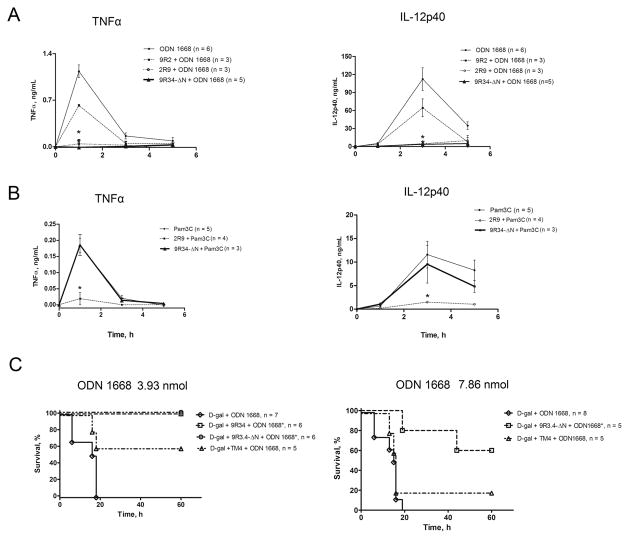

9R34-ΔN blunts ODN 1668-induced systemic cytokine response in vivo and protects against TLR9-induced lethality

To test the in vivo efficacy and specificity of 9R34-ΔN, C57BL/6J mice were mock-treated or treated i.p. with a single dose of inhibitory or control peptide (200 nmol/mouse) and challenged with TLR9 agonist ODN 1668 (7.86 nmol/mouse) or TLR2/1 agonist Pam3C (67 nmol/mouse) 1 hour later. Plasma concentrations of TNF-α and IL-12p40 were measured 1, 3, and 5 hours after the challenge. Both TLR agonists increased concentrations of TNF-α and IL-12p40 in 1 hour samples from below the limit of detection to ~1.2 and ~6 ng/mL in case of ODN 1668, and to 0.12 and 1 ng/mL after treatment with Pam3C (Fig. 5). The concentration of TNF-α dropped rapidly to near basal levels in 3-hour samples, whereas circulating IL-12p40 continued to grow and increased more than ten-fold in next two hours, peaking at ~110 ng/mL in the ODN 1668-treated mice and at ~11 ng/mL in mice challenged with Pam3C (Fig. 5). ODN 1668-treated mice pretreated with 9R34-ΔN eliminated the 1 h TNF-α peak and decreased the IL-12p40 peak by approximately 25-fold in the 3 h samples (Fig. 5A). In a sharp contrast to the effect on the ODN-induced cytokines, 9R34-ΔN did not affect cytokine levels induced by TLR2 agonist Pam3C (Fig. 5B), thereby confirming the cell culture data presented in Figure 2A. Our previous studies have identified 2R9, a TLR2-derived peptide that inhibits TLR2, TLR4, TLR7, and TLR9, primarily because it targets an adapter shared by these TLRs (37). As expected, 2R9 suppressed cytokine induction elicited by either ODN 1668 or Pam3C; whereas 9R34-ΔN selectively inhibited only the ODN 1668-induced cytokines (Fig. 5A and 5B). Negative control peptide 9R2 (this peptide did not inhibit TLR9 in cell culture experiments (Fig. 1)) was tested in vivo only with respect to ODN-induced cytokines; as expected, 9R2 did not significantly reduce the ODN-induced cytokine levels in mice (Fig. 5A). These data clearly demonstrate that TLR9 inhibition by 9R34-ΔN is selective.

Figure 5.

9R34-ΔN inhibits ODN 1668-induced systemic cytokines in vivo and protects D-galactosamine pretreated mice from ODN 1668-induced lethality. (A) Plasma TNFα and IL-12p40 levels in mice following administration of ODN 1668. (B) Plasma TNFα and IL-12p40 levels in mice following administration of Pam3C. Data shown in panels A and B represent the means ± SEM obtained in at least three independent experiments. The statistical significance of changes in cytokine concentrations was determined by a two-way ANOVA test; *p < 0.001. (C) Survival of D-Gal pretreated mice after treatment with ODN 1668. The statistical significance of changes in mortality and survival time was determined by the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test; *p < 0.01.

With the exception for LPS, administration of a purified TLR agonist is not lethal to mice. Mice, however, can be sensitized to TLR agonists by pretreatment with D-galactosamine (D-Gal) (73). We tested if 9R34-ΔN protects D-Gal-pretreated mice from TLR9-induced lethality. Mice were first ip administered with D-Gal at the dose of 20 mg/mouse. Thirty minutes later mice were mock-treated with PBS or treated with a CPDP at the dose 200 nmol/mouse. ODN 1668 was administered 1 hour after peptide treatment at the dose of 3.93 or 7.86 nmol/mouse. Either ODN 1668 dose used induced 100% lethality in the D-Gal-pretreated mice (Fig. 5). 9R34 or 9R34-ΔN administered i.p. provided full protection to mice that received ODN 1668 at the lower dose of 3.93 nmol/mouse (Fig. 5C). TM4, a potent inhibitor of TLR4 derived from TRAM, fully protected mice against mortality caused by LPS (55). TM4 was less effective than 9R34-ΔN in protection against ODN-induced lethality (Fig. 5C). Partial protection observed after TM4 treatment apparently is due to suppression of TLR4-mediated inflammatory response and consequent injury caused by endogenous danger-associated molecules that may be produced in the body in response to mechanical, chemical, or biological injury (74). Both 9R34-ΔN and TM4 were less protective when tested in mice treated with a higher ODN 1668 dose (7.86 nmol /mouse). Nevertheless, 9R34-ΔN rescued more than 50% of mice challenged with this higher dose of ODN 1668 (Fig. 5C).

DISCUSSION

This study examines peptide library derived from the TLR9 TIR for a dominant-negative effect on TLR9 signaling and so extends our previous research that has screened analogous peptides from TIR domains of TLR4, TLR2, and their adapters and co-receptors (18, 37, 38, 53, 55, 75). Each peptide of the TLR9 library represents a patch of TIR surface that might mediate a TIR-TIR interaction within the primary receptor complex (Table 1, Fig. 1). Screening results have suggested that peptides 9R34, 9R34 modifications, 9R9, and 9R11 inhibit TLR9 signaling. These inhibitory peptides represent three non-contiguous surface regions of TLR9 TIR, each of which might represent a separate TIR-TIR interface (Fig. 1).

Comparison of inhibition pattern within TLR9 peptide library (Fig. 1) with that of previously screened TLR libraries (18, 37, 38) suggests that the location of TIR segments capable of blocking TIR-TIR interactions is generally conserved in TLRs, yet there are some differences. Thus, peptides derived from the AB loop, i.e., Region 3 peptides, were inhibitory in TLR4, TLR2, and TLR9 sets (Fig. 1 and (18, 37)). Inhibitory ability of BB loop peptides (these peptides were designated as Region 4 peptides), however, differed in these three peptide sets. The BB loop peptides of TLR4 and TLR2 sets inhibited (18, 36), whereas the BB loop peptide of TLR9 did not (Fig. 1) (the TLR2 BB loop peptide inhibited TLR2 only when leucine located at the border of TLR2 Regions 3 and 4 was included (36, 37)). It should be noted, however, that peptides from AB or BB loop of TLR2 co-receptors did not inhibit the TLR2-mediated signaling (38, 57). In the TLR9 set, peptides derived from the region centered on the Region 3 and 4 border, peptides 9R34 and 9R34-ΔN, inhibited TLR9 signaling more potently than 9R3 (Figs. 1 and 6). Notably, all inhibitory peptides derived from Region 3 or 4 of a TLR targeted the TLR TIR of corresponding dimerization partner (18, 37, 67), suggesting that this region may serve as the receptor dimerization surface. The TLR9 inhibitory peptide 9R34-ΔN followed same pattern and bound the receptor TIR domain (Fig. 4). These data suggest that the position of TLR dimerization interface is generally conserved in the TLR family, with one TLR TIR dimerization interface being formed by a broad area that may include residues of AB and/or BB loops and β-strand B (Figs. 1D–E and 6A–B). Because the position of this dimerization interface slightly varies in different TIRs and is formed by not conserved amino acid sequences, this broad area is shown as Surface 1 (S1) in Figure 6.

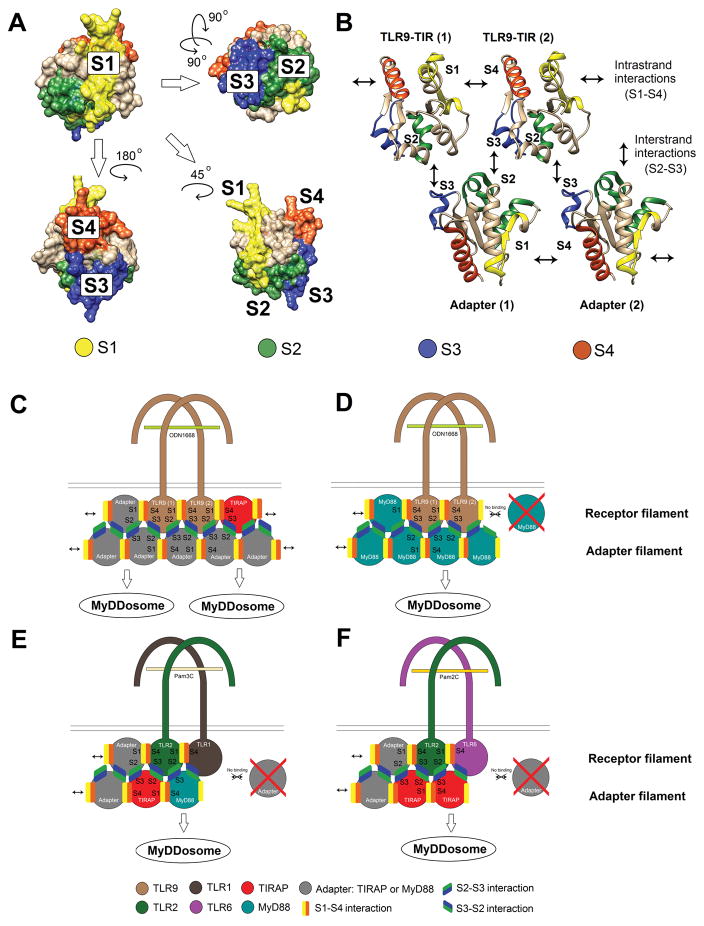

Figure 6. Putative TIR interaction sites and the modes of TIR domain interactions in TLR signaling complexes.

(A) Four TIR surfaces (S1 – S4) that mediate the assembly of primary TLR signaling complexes. Surface 1 (S1) (yellow highlight) and Surface 4 (S4) (orange highlight) are located on opposite TIR sides, near β-strands B and E, the strands that form lateral, surface-exposed edges of the β-sheet. Surface 2 (S2) (shown in green) is formed by α-helices B and C, whereas Surface 3 (dark blue) is formed by α-helix D and may include adjacent loops. In the TLR9 peptide set, S1, S3, and S4 are represented by peptide 9R34, 9R9, and 9R11, respectively; whereas of peptides that should jointly form S2, i.e., 9R5 and 9R6, only 9R6 inhibited weakly (Fig. 1). The images show a homology model of TLR9 TIR computationally built using TLR2 TIR protein database file (pdb) (pdb ID: 1o77) as a template.

(B) TIR domain interactions that initiate intracellular TLR signaling. Two upper TIR domains of this panel represent dimerized receptor TIR domains; whereas two lower TIRs represent adapters. The upper TIRs show same TLR9 TIR model as in panel A, but shown in the ribbon style. Two lower TIRs are representations of TIRAP TIR model (pdb ID: 5UZB, chain A). S1 and S4 mutually interact to mediate the intrastrand TIR-TIR interactions of the complex. S1 and S4 of TLR TIRs form receptor dimers. These Surfaces may also recruit adapters through lateral, intrastrand interactions, thereby leading to elongation of the complex in either one or two directions. Color coding of TIR segments in panel B correspond to that in panel A.

S2 interacts with S3, forming the interstrand interactions. S2 and S3 are located on the same TIR hemisphere; these surfaces mediate interstrand receptor-adapter and adapter-adapter interactions (only receptor-adapter S2 – S3 interactions are shown in panel B). Surfaces 2 and 3 of one TIR domain interact with cognate surfaces of two separate TIR domains of the opposite strand in the cooperative mode (18).

(C) Schematics of adapter recruitment to activated TLR9. TLR9 TIR dimers recruit adapters through intrastrand and interstrand interactions. The TLR9 TIR complex elongates bidirectionally in the presence of TIRAP and MyD88. Bidirectional elongation of TLR9 signaling protofilaments is possible due to ability of TLR9 S1 to interact with TIRAP and the ability of TLR9 S4 to bind either TIRAP or MyD88. Adapter-adapter S2–S3 interstrand interactions occur after elongation of the receptor filament through intrafilament S1–S4 interactions.

(D) Schematics of MyD88 recruitment to activated TLR9 in the absence of TIRAP. In the absence of TIRAP, the TLR9 filaments elongate unidirectionally only through S4 surface of the dimer.

(E and F) TLR2/1 and TLR2/6 signaling filament elongation models. TLR2 filaments elongate unidirectionally because S1 of both TLR2 coreceptors are inept in binding the TLR2 adapters (38, 57). Strong TIRAP-dependence of TLR2 signaling is due to high affinity TLR2-TIRAP interaction through S3 of TLR2 (37).

Binding studies have suggested that 9R34-ΔN binds not only TLR9 TIR, but also TIRAP TIR (yet with apparently lower affinity), but does not interact with MyD88 TIR (Fig. 4). Such a binding profile of 9R34-ΔN is consistent with models of primary receptor complex in which TLR TIR dimer is formed by an asymmetric interaction, in which Surface 1 of one TLR TIR domain mediates TLR TIR dimerization, whereas the same region of the second TLR of the dimer is available for TIRAP recruitment (Fig. 6 and references (18, 76, 77)).

Peptides from Region 9 (this region includes α-helix D and DE loop) were inhibitory in all TLR TIR libraries tested to date (18, 37, 38). Notably, all previously identified Region 9 TLR peptides preferentially bound adapter TIR domains. Thus, 4R9, a TLR4 peptide, did not bind TLR4 TIR (18), but co-immunoprecipitated with TIRAP (75). 2R9, peptide from Region 9 of TLR2, was TIRAP-selective in a cell-based FRET assay and bound recombinant TIRAP with nanomolar affinity (37). TLR1 and TLR6 Region 9 peptides inhibited cognate receptors and bound MyD88 and TIRAP, respectively (38). These findings suggest that α-helix D of TLR TIR domains is an essential part of the adapter recruitment site. The TLR9 peptide 9R9 inhibited signaling weaker than 9R34 or 9R11 (Fig. 1A and B). For this reason, we could not directly confirm if this peptide indeed targets a TLR adapter. The area that corresponds to 9R9 and includes helix D and neighboring loops is shown as Surface 3 (S3) in Figure 6.

The third inhibitory peptide of TLR9 library, 9R11, corresponds to α-helix E (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, peptide 4RαE from α-helix E of TLR4 also inhibited cognate signaling (18). Peptides from α-helices E of TLR1, 2, or 6, however, did not affect TLR2 signaling; although TLR1 and TLR6 peptides from a neighboring region that included DE and EE loops, and β-strand E inhibited (37, 38). A cell-based binding assay has demonstrated that 4RαE binds the TLR4 TIR (18). Consistently, new data show that the structurally homologous TLR9 peptide, 9R11, also binds to the receptor TIR (Fig. 4). 9R11, however, demonstrated a multispecific binding as this peptide also bound TIRAP and, to a lesser degree, MyD88 (Fig. 4C). Thus, inhibition profiles obtained for TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 peptide libraries collectively reveal a significant similarity and suggest a common mode of TLR TIR dimerization in which one TIR of the dimer interacts with other through Surface 1, a large area that is centered on the β-strand B and may include either BB or AB loop, or parts of both (Fig. 6). Surface 1 appears to interact asymmetrically with the region generally located on the opposite surface of the TIR, in the vicinity of α-helix and β-strand E (Surface 4). It should be noted that the surface area near helix E is highly fragmented; therefore, in addition to the helix E residues, the second dimerization interface may include isolated residues from neighboring regions, i.e., β-strand E and the adjacent loops, the N-terminal half of β-strand D, and residues of the most C-terminal round of α-helix D. The TLR TIR interaction mechanism suggested by TIR peptide screenings is generally in line with several earlier proposed, asymmetric TIR-TIR interaction models, in which broad ‘β-strand B region’ of one TIR interacts with opposite surface of the second TIR through α-helix E and/or neighboring regions (18, 76, 78).

The most recent and detailed model for the assembly of TIR signaling complexes that underlie the adapter recruitment to activated TLRs was proposed by Ve et al. (78). This model resulted from the study of filamentous structures spontaneously formed in solution by TIR domains of TIRAP, MyD88, or a mixture of these proteins. Ve et al. postulated that interactions of TIR domains in the primary TLR signaling complexes resemble interactions in the double-stranded protofilaments that comprise larger TIRAP filaments (reference (78) and Fig. 6C). Two types of TIR-TIR interactions mediate the assembly of the double stranded TIR filaments. TIR interactions within the strands are through two regions that are located near β-strands that form two opposite edges of the central β-sheet, strands B and E (these areas remarkably well correspond to Surfaces 1 and 4 suggested by decoy peptide screenings (Fig. 6)).

Interactions of TIR domains that belong to different strands of the double-stranded TIRAP protofilament are mediated by two separate, mutually interacting surfaces ((78) and Fig. 6). One interstrand interface of TIRAP protofilaments included residues of α-helix D and CD loop; this interface corresponds to Surface 3 (Fig. 6). The second interstrand interface of TIRAP protofilaments was jointly formed by helices B and C (78). The corresponding residues of TLR9 are indicated as Surface 2 (S2) in Figure 6. Importantly, interaction surfaces in the TIRAP protofilament match to the putative TIR-TIR interfaces suggested by previous studies of TIRAP-derived decoy peptides (53, 79, 80). Thus, early studies suggested that the BB loop peptide can block important TIRAP functions (79, 80). Couture et al. later found additional peptides (TR3, TR5, TR6, TR9, and TR11) that inhibit TIRAP-mediated signaling and specified that signaling inhibition by TIRAP BB loop peptide critically depends on the N-terminal leucine (53). TIRAP-derived inhibitory peptides TR5 and TR6, first reported by Couture et al., correspond to the second interfilament interface of TIRAP protofilaments, indicated as S2 in Figure 6. Peptide TR9 represented Surface 3, whereas TR11 and TR3 respectively corresponded to S4 and S1 (53, 78).

Thus, screening of TLR9-derived peptides reveals significant topological similarity of positions of new inhibitory peptides with that in previously screened peptide libraries. Moreover, the inhibitory peptides come from regions that are structurally homologous to TIR-TIR interfaces in the TIRAP protofilaments (78). These findings together support the hypothesis of structural similarity of receptor and adapter TIR interactions in the signal-initiating complexes; yet, particular TIRs of the complex may interact through slightly different structural regions. Particularly, our data suggest that the AB loop of TLRs play more important role in TIR-TIR recognition than the BB loop. The finding that TIR-TIR interface positions are structurally conserved is remarkable considering sequence dissimilarity of corresponding segments. An example of sequence dissimilarity of corresponding interface regions are sequences of TIRAP, TLR4, TLR2, and TLR9 inhibitory peptides from Region 9 and 11 (TR9: AAYPPELRFMYYVD; 4R9: LRQQVELYRLLSR; 2R9: PQRFCKLRKIMNT; TR11: GGFYQVKEAVIHY; 4αE: HIFWRRLKNALLD; 9R11: RSFWAQLGMALTRD).

The surfaces that mediate TIR-TIR interactions are highlighted in Figure 6 as Surfaces 1 – 4. In TLR9, Surfaces 1 and 4 correspond to peptides 9R34 and 9R11. These surfaces mediate dimerization of TLR TIRs and also adapter recruitment through lateral intrafilament interactions (Fig. 6B). Surfaces 2 and 3 in TLR9 correspond to peptides 9R6 and 9R9 (9R6 exhibited partial activity in respect to TNF-α and IL-12p40 mRNA (Fig. 1A)). These Surfaces recruit adapter TIRs that initiate the formation of the second strand of the primary TIR complex (Fig. 6B). The second strand stabilizes the complex and provides sufficient number of MyD88 molecules to initiate MyDDosome formation (Fig. 6).

Experimental data support this model of TIR domain interactions in several ways. One prediction from the filamentous, double-stranded structure of the signaling-initiating TIR complex is that both surfaces that mediate TLR TIR dimerization may be responsible for adapter recruitment through the intrastrand interactions (Fig. 6B and C). Our data confirm this prediction because both inhibitory peptides that correspond to two separate TLR9 dimerization interfaces, 9R34-ΔN and 9R11, demonstrate multispecific binding. Peptide 9R34-ΔN, from S1, binds TLR9 and TIRAP TIR domains, not MyD88, whereas 9R11 (this peptide represents S4) interacts with all relevant TIR domains (Fig. 4C).

Another consequence from the adapter recruitment model suggested by TIRAP filament structure and decoy peptide screenings is that adapters are independently recruited to filament ends through different surfaces of the receptor dimer that may have different binding specificities. This, in turn, implies that the initial receptor complex can elongate from either or both ends (Fig. 6C–F). In the case of TLR9, peptide from Surface 1 binds TIRAP, not MyD88; whereas the peptide from opposite Surface 4 can bind either TIRAP or MyD88 (Figs. 4 and 6C). Such binding preferences suggest that the initial complex can elongate bidirectionally in the presence of TIRAP and MyD88 (Fig. 6C). In the absence of TIRAP, the TLR9 complex can elongate only in one direction, through MyD88 recruitment only to Surface 4 of the TLR9 TIR dimer (Fig. 6D). Such models reconcile previous discussions on the role of TIRAP in TLR9 signaling. While early studies concluded that TIRAP is not required for TLR9 signaling (81, 82), it was later discovered that TLR9 responses to certain viruses are critically diminished in TIRAP absence and the TIRAP-targeting peptide strongly suppresses TLR9 signaling in wild-type cells (27, 37). The TIRAP-dependent bidirectional elongation of protosignalosomes explains both the ability of TLR9 to signal in TIRAP-deficient models and the sensitivity of TLR9 responses to TIRAP targeting in wild type cells.

Latty et al. recently applied single-molecule fluorescence microscopy to study formation of MyDDosomes in response to TLR4 stimulation (83). Intriguingly, authors observed that a large LPS dose caused formation of “super MyDDosomes,” the signaling complexes that are comprised of twice as many MyD88 molecules as regular MyDDosomes (83). These observations support the possibility of bidirectional protofilament elongation that may cause formation of two MyDDosomes per one TLR4 dimer simultaneously, analogously to the schematic shown in Figure 6C for TLR9.

Our previous studies demonstrated that peptide derived from Surface 1 of TLR2, 2R3, inhibits TLR2/1 and TLR2/6 signaling and binds both TLR2 co-receptors, whereas peptides from Surface 1 of TLR1 or TLR6 do not inhibit (37, 38). We also found that Surface 3 peptides from TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 inhibit corresponding signaling and bind MyD88 or TIRAP (37, 38). These findings suggest that primary TLR2 complexes elongate in the unidirectional mode, as schematically shown in Figures 6E and 6F.

In summary, this study identifies TLR9-derived inhibitory peptides that block TLR9 signaling in vitro and in vivo and suggest a common mode of TIR domain interactions in the primary receptor complex. Interacting in that mode, TIR domains form a double-stranded, parallel structure that can elongate from one or both ends. Interactions within each filament are mediated by regions located near β-strands that form the edges of TIR β-sheet; whereas interfilament interactions are through two sites, one of which is predominantly formed by helix D and another combines residues of helices B and C.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AI-082299 (VYT), RR 26370 (JRL), GM125976 and OD019975 (JRL).

Abbreviations used in this article

- BMDM

bone marrow-derived macrophages

- Cer

Cerulean

- CPDP

cell-permeating decoy peptides

- D-Gal

D-galactosamine

- FLIM

fluorescence lifetime imaging

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- ODN

oligonucleotide

- pdb

protein database file

- TIR

Toll/IL-1R homology domain

- TIRAP

TIR domain-containing adapter protein, also known as Mal

- TRAM

TIR domain-containing adapter inducing IFN-β–related adapter molecule

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Patent pending.

References

- 1.Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity. 2011;34:637–650. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornblit B, Muller K. Sensing danger: toll-like receptors and outcome in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52:499–505. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai Y, Gallo RL. Toll-like receptors in skin infections and inflammatory diseases. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2008;8:144–155. doi: 10.2174/1871526510808030144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Neill LA, Bowie AG. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature reviews Immunology. 2007;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nri2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Y, Fang L, Peng L, Qiu W. TLR9 and its signaling pathway in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2017;373:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook DN, Pisetsky DS, Schwartz DA. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human disease. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:975–979. doi: 10.1038/ni1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy L, O’Reilly SC. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases: recent and emerging translational developments. Immunotargets Ther. 2016;5:69–80. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S89795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatai H, Lepelley A, Zeng W, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Toll-Like Receptor 11 (TLR11) Interacts with Flagellin and Profilin through Disparate Mechanisms. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedhli D, Moire N, Akbar H, Laurent F, Heraut B, Dimier-Poisson I, Mevelec MN. The antigen-specific response to Toxoplasma gondii profilin, a TLR11/12 ligand, depends on its intrinsic adjuvant properties. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2016;205:345–352. doi: 10.1007/s00430-016-0452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koblansky AA, Jankovic D, Oh H, Hieny S, Sungnak W, Mathur R, Hayden MS, Akira S, Sher A, Ghosh S. Recognition of profilin by Toll-like receptor 12 is critical for host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity. 2013;38:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oosting M, Cheng SC, Bolscher JM, Vestering-Stenger R, Plantinga TS, Verschueren IC, Arts P, Garritsen A, van Eenennaam H, Sturm P, Kullberg BJ, Hoischen A, Adema GJ, van der Meer JW, Netea MG, Joosten LA. Human TLR10 is an anti-inflammatory pattern-recognition receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E4478–4484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410293111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashkar AA, Rosenthal KL. Toll-like receptor 9, CpG DNA and innate immunity. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:545–556. doi: 10.2174/1566524023362159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohto U, Shibata T, Tanji H, Ishida H, Krayukhina E, Uchiyama S, Miyake K, Shimizu T. Structural basis of CpG and inhibitory DNA recognition by Toll-like receptor 9. Nature. 2015;520:702–705. doi: 10.1038/nature14138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirk P, Bazan JF. Pathogen recognition: TLRs throw us a curve. Immunity. 2005;23:347–350. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huyton T, Rossjohn J, Wilce M. Toll-like receptors: structural pieces of a curve-shaped puzzle. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:406–410. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Botos I, Segal DM, Davies DR. The structural biology of Toll-like receptors. Structure. 2011;19:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toshchakov VY, Szmacinski H, Couture LA, Lakowicz JR, Vogel SN. Targeting TLR4 signaling by TLR4 Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-derived decoy peptides: identification of the TLR4 Toll/IL-1 receptor domain dimerization interface. J Immunol. 2011;186:4819–4827. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrao R, Li J, Bergamin E, Wu H. Structural insights into the assembly of large oligomeric signalosomes in the Toll-like receptor-interleukin-1 receptor superfamily. Science signaling. 2012;5:re3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gay NJ, Symmons MF, Gangloff M, Bryant CE. Assembly and localization of Toll-like receptor signalling complexes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:546–558. doi: 10.1038/nri3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin SC, Lo YC, Wu H. Helical assembly in the MyD88-IRAK4-IRAK2 complex in TLR/IL-1R signalling. Nature. 2010;465:885–890. doi: 10.1038/nature09121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motshwene PG, Moncrieffe MC, Grossmann JG, Kao C, Ayaluru M, Sandercock AM, Robinson CV, Latz E, Gay NJ. An oligomeric signaling platform formed by the Toll-like receptor signal transducers MyD88 and IRAK-4. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25404–25411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medzhitov R, Horng T. Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:692–703. doi: 10.1038/nri2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han KJ, Su X, Xu LG, Bin LH, Zhang J, Shu HB. Mechanisms of the TRIF-induced interferon-stimulated response element and NF-kappaB activation and apoptosis pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15652–15661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MH, Yoo DS, Lee SY, Byeon SE, Lee YG, Min T, Rho HS, Rhee MH, Lee J, Cho JY. The TRIF/TBK1/IRF-3 activation pathway is the primary inhibitory target of resveratrol, contributing to its broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effects. Pharmazie. 2011;66:293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagan JC, Medzhitov R. Phosphoinositide-mediated adaptor recruitment controls Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. 2006;125:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonham KS, Orzalli MH, Hayashi K, Wolf AI, Glanemann C, Weninger W, Iwasaki A, Knipe DM, Kagan JC. A promiscuous lipid-binding protein diversifies the subcellular sites of toll-like receptor signal transduction. Cell. 2014;156:705–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunne A, Ejdeback M, Ludidi PL, O’Neill LA, Gay NJ. Structural complementarity of Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domains in Toll-like receptors and the adaptors Mal and MyD88. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41443–41451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301742200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patterson NJ, Werling D. To con protection: TIR-domain containing proteins (Tcp) and innate immune evasion. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2013;155:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narayanan KB, Park HH. Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain-mediated cellular signaling pathways. Apoptosis. 2015;20:196–209. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-1073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rock FL, Hardiman G, Timans JC, Kastelein RA, Bazan JF. A family of human receptors structurally related to Drosophila Toll. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:588–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Y, Tao X, Shen B, Horng T, Medzhitov R, Manley JL, Tong L. Structural basis for signal transduction by the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domains. Nature. 2000;408:111–115. doi: 10.1038/35040600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sims JE, March CJ, Cosman D, Widmer MB, MacDonald HR, McMahan CJ, Grubin CE, Wignall JM, Jackson JL, Call SM, et al. cDNA expression cloning of the IL-1 receptor, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Science. 1988;241:585–589. doi: 10.1126/science.2969618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider DS, Hudson KL, Lin TY, Anderson KV. Dominant and recessive mutations define functional domains of Toll, a transmembrane protein required for dorsal-ventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1991;5:797–807. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nunez Miguel R, Wong J, Westoll JF, Brooks HJ, O’Neill LA, Gay NJ, Bryant CE, Monie TP. A dimer of the Toll-like receptor 4 cytoplasmic domain provides a specific scaffold for the recruitment of signalling adaptor proteins. PloS one. 2007;2:e788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toshchakov VY, Vogel SN. Cell-penetrating TIR BB loop decoy peptides a novel class of TLR signaling inhibitors and a tool to study topology of TIR-TIR interactions. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2007;7:1035–1050. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.7.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piao W, Shirey KA, Ru LW, Lai W, Szmacinski H, Snyder GA, Sundberg EJ, Lakowicz JR, Vogel SN, Toshchakov VY. A Decoy Peptide that Disrupts TIRAP Recruitment to TLRs Is Protective in a Murine Model of Influenza. Cell reports. 2015;11:1941–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piao W, Ru LW, Toshchakov VY. Differential adapter recruitment by TLR2 co-receptors. Pathogens and disease. 2016:74. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftw043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monie TP, Moncrieffe MC, Gay NJ. Structure and regulation of cytoplasmic adapter proteins involved in innate immune signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:161–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Gregorio J, Chan JH, Uematsu S, Akira S, Chang B, Duramad O, Coffman RL. Nucleic acids of mammalian origin can act as endogenous ligands for Toll-like receptors and may promote systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1131–1139. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roelofs MF, Joosten LA, Abdollahi-Roodsaz S, van Lieshout AW, Sprong T, van den Hoogen FH, van den Berg WB, Radstake TR. The expression of toll-like receptors 3 and 7 in rheumatoid arthritis synovium is increased and costimulation of toll-like receptors 3, 4, and 7/8 results in synergistic cytokine production by dendritic cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2313–2322. doi: 10.1002/art.21278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curtiss LK, Tobias PS. Emerging role of Toll-like receptors in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S340–345. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800056-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciechomska M, Cant R, Finnigan J, van Laar JM, O’Reilly S. Role of toll-like receptors in systemic sclerosis. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2013;15:e9. doi: 10.1017/erm.2013.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Falck-Hansen M, Kassiteridi C, Monaco C. Toll-like receptors in atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:14008–14023. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Celhar T, Fairhurst AM. Toll-like receptors in systemic lupus erythematosus: potential for personalized treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:265. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thwaites R, Chamberlain G, Sacre S. Emerging role of endosomal toll-like receptors in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2014;5:1. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhattacharyya S, Varga J. Emerging roles of innate immune signaling and toll-like receptors in fibrosis and systemic sclerosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:474. doi: 10.1007/s11926-014-0474-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu YW, Tang W, Zuo JP. Toll-like receptors: potential targets for lupus treatment. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36:1395–1407. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Neill LA, Bryant CE, Doyle SL. Therapeutic targeting of Toll-like receptors for infectious and inflammatory diseases and cancer. Pharmacological reviews. 2009;61:177–197. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Connolly DJ, O’Neill LA. New developments in Toll-like receptor targeted therapeutics. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2012;12:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Derossi D, Joliot AH, Chassaing G, Prochiantz A. The third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10444–10450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakase I, Konishi Y, Ueda M, Saji H, Futaki S. Accumulation of arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides in tumors and the potential for anticancer drug delivery in vivo. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2012;159:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Couture LA, Piao W, Ru LW, Vogel SN, Toshchakov VY. Targeting Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling by Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adapter protein/MyD88 adapter-like (TIRAP/Mal)-derived decoy peptides. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24641–24648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.360925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarko D, Beijer B, Garcia Boy R, Nothelfer EM, Leotta K, Eisenhut M, Altmann A, Haberkorn U, Mier W. The pharmacokinetics of cell-penetrating peptides. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2010;7:2224–2231. doi: 10.1021/mp100223d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Piao W, Vogel SN, Toshchakov VY. Inhibition of TLR4 signaling by TRAM-derived decoy peptides in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2013;190:2263–2272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piao WJ, Ru LW, Piepenbrink KH, Sundberg EJ, Vogel SN, Toshchakov VY. Recruitment of TLR adapter TRIF to TLR4 signaling complex is mediated by the second helical region of TRIF TIR domain. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:19036–19041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313575110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toshchakov VY, Fenton MJ, Vogel SN. Cutting Edge: Differential inhibition of TLR signaling pathways by cell-permeable peptides representing BB loops of TLRs. J Immunol. 2007;178:2655–2660. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu X, Fu Y, Tian Y, Zhang Z, Zhang W, Gao X, Lu X, Cao Y, Zhang N. The anti-inflammatory effect of TR6 on LPS-induced mastitis in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;30:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu X, Tian Y, Qu S, Cao Y, Li S, Zhang W, Zhang Z, Zhang N, Fu Y. Protective effect of TM6 on LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:572. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00551-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allette YM, Kim Y, Randolph AL, Smith JA, Ripsch MS, White FA. Decoy peptide targeted to Toll-IL-1R domain inhibits LPS and TLR4-active metabolite morphine-3 glucuronide sensitization of sensory neurons. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3741. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03447-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lysakova-Devine T, Keogh B, Harrington B, Nagpal K, Halle A, Golenbock DT, Monie T, Bowie AG. Viral inhibitory peptide of TLR4, a peptide derived from vaccinia protein A46, specifically inhibits TLR4 by directly targeting MyD88 adaptor-like and TRIF-related adaptor molecule. J Immunol. 2010;185:4261–4271. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Snyder GA, Deredge D, Waldhuber A, Fresquez T, Wilkins DZ, Smith PT, Durr S, Cirl C, Jiang J, Jennings W, Luchetti T, Snyder N, Sundberg EJ, Wintrode P, Miethke T, Xiao TS. Crystal structures of the Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domains from the Brucella protein TcpB and host adaptor TIRAP reveal mechanisms of molecular mimicry. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:669–679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.523407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ke Y, Li W, Wang Y, Yang M, Guo J, Zhan S, Du X, Wang Z, Yang M, Li J, Li W, Chen Z. Inhibition of TLR4 signaling by Brucella TIR-containing protein TcpB-derived decoy peptides. Int J Med Microbiol. 2016;306:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weischenfeldt J, Porse B. Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMM): Isolation and Applications. CSH Protoc. 2008;2008 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5080. pdb prot5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, Weis JH, Vogel SN, Weis JJ. Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 2000;165:618–622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Szmacinski H, Toshchakov V, Lakowicz JR. Application of phasor plot and autofluorescence correction for study of heterogeneous cell population. Journal of biomedical optics. 2014;19:046017. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.19.4.046017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Remmert M, Biegert A, Hauser A, Soding J. HHblits: lightning-fast iterative protein sequence searching by HMM-HMM alignment. Nat Methods. 2011;9:173–175. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of computational chemistry. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zanoni I, Tan Y, Di Gioia M, Broggi A, Ruan J, Shi J, Donado CA, Shao F, Wu H, Springstead JR, Kagan JC. An endogenous caspase-11 ligand elicits interleukin-1 release from living dendritic cells. Science. 2016;352:1232–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Silverstein R. D-galactosamine lethality model: scope and limitations. Journal of endotoxin research. 2004;10:147–162. doi: 10.1179/096805104225004879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shirey KA, Lai W, Scott AJ, Lipsky M, Mistry P, Pletneva LM, Karp CL, McAlees J, Gioannini TL, Weiss J, Chen WH, Ernst RK, Rossignol DP, Gusovsky F, Blanco JC, Vogel SN. The TLR4 antagonist Eritoran protects mice from lethal influenza infection. Nature. 2013;497:498–502. doi: 10.1038/nature12118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Piao W, Ru LW, Piepenbrink KH, Sundberg EJ, Vogel SN, Toshchakov VY. Recruitment of TLR adapter TRIF to TLR4 signaling complex is mediated by the second helical region of TRIF TIR domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:19036–19041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313575110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jiang Z, Georgel P, Li C, Choe J, Crozat K, Rutschmann S, Du X, Bigby T, Mudd S, Sovath S, Wilson IA, Olson A, Beutler B. Details of Toll-like receptor:adapter interaction revealed by germ-line mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10961–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603804103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ve T, Williams SJ, Kobe B. Structure and function of Toll/interleukin-1 receptor/resistance protein (TIR) domains. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death. 2015;20:250–261. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-1064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ve T, Vajjhala PR, Hedger A, Croll T, DiMaio F, Horsefield S, Yu X, Lavrencic P, Hassan Z, Morgan GP, Mansell A, Mobli M, O’Carroll A, Chauvin B, Gambin Y, Sierecki E, Landsberg MJ, Stacey KJ, Egelman EH, Kobe B. Structural basis of TIR-domain-assembly formation in MAL- and MyD88-dependent TLR4 signaling. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2017;24:743–751. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Horng T, Barton GM, Medzhitov R. TIRAP: an adapter molecule in the Toll signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:835–841. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Toshchakov V, Jones BW, Perera PY, Thomas K, Cody MJ, Zhang SL, Williams BRG, Major J, Hamilton TA, Fenton MJ, Vogel SN. TLR4, but not TLR2, mediates IFN-beta-induced STAT1 alpha/beta-dependent gene expression in macrophages. Nature Immunology. 2002;3:392–398. doi: 10.1038/ni774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Horng T, Barton GM, Flavell RA, Medzhitov R. The adaptor molecule TIRAP provides signalling specificity for Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;420:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nature01180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Sanjo H, Uematsu S, Kaisho T, Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kobayashi M, Fujita T, Takeda K, Akira S. Essential role for TIRAP in activation of the signalling cascade shared by TLR2 and TLR4. Nature. 2002;420:324–329. doi: 10.1038/nature01182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Latty S, Sakai J, Hopkins L, Verstak B, Paramo T, Berglund NA, Gay NJ, Bond PJ, Klenerman D, Bryant CE. Activation of Toll-like receptors nucleates assembly of the MyDDosome signaling hub. eLife. 2018:7. doi: 10.7554/eLife.31377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.