Abstract

Background

Invasive candidiasis is an important cause of sepsis in extremely low birth weight infants (ELBW, <1000g), is often fatal, and frequently results in neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) among survivors. We sought to assess the antifungal minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) distribution for Candida in ELBW infants and evaluate the association between antifungal resistance and death or NDI.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network study, “Early Diagnosis of Nosocomial Candidiasis”. MIC values were determined for fluconazole, amphotericin B, and micafungin. NDI was assessed at 18–22 months adjusted age using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID). An infant was defined as having a resistant Candida isolate if ≥1 positive cultures from normally sterile sites (blood, cerebrospinal fluid or urine) were resistant to ≥1 antifungal agent. In addition to resistance status, we categorized fungal isolates according to MIC values (low and high). The association between death/NDI and MIC level was determined using logistic regression, controlling for gestational age (GA) and BSID (II or III).

Results

Among 137 ELBW infants with IC, MICs were determined for 308 isolates from 110 (80%) infants. Three Candida isolates from 3 infants were resistant to fluconazole. None were resistant to amphotericin B or micafungin. No significant difference in death, NDI, or death/NDI between groups with low and high MICs was observed.

Conclusions

Antifungal resistance was rare among infecting Candida isolates, and MIC level was not associated with increased risk of death or NDI in this cohort of ELBW infants.

Keywords: Neonatal candidiasis, minimal inhibitory concentration, antifungal, mortality, neurodevelopmental impairment

Introduction

In premature infants, Candida is an important cause of late-onset sepsis.1–3 Among extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infants (<1000 g birth weight), the incidence of invasive candidiasis (IC) varies across NICUs from 0.6% to 8%.2,4–7 Consequences of IC in this population are severe with 14–40% mortality and 30–70% neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) among survivors.3,4,8,9 Amphotericin B deoxycholate or fluconazole are recommended as first line therapy; echinocandins, such as micafungin, are an alternate treatment option.10

The most common isolates among premature infants with IC are C. albicans and C. parapsilosis, organisms which are generally susceptible to first line antifungal therapy.4,6,7 However, there has been increase of the proportion of non-albicans Candida which are associated with resistance to fluconazole.6,11

Candida resistance status is based on clinical breakpoints (CBPs), which are determined following consideration of drug pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) parameters, correlations between clinical outcomes and minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC), as well as MIC distributions of wild-type fungal isolates.12 Clinical data supporting CBPs are usually derived from prospective antifungal trials primarily involving adults.12,13 Antifungal PK are not the same between premature infants and adults.14 Moreover, clinical course and outcome of IC differs in premature infants who are at higher risk of meningoencephalitis and NDI.15–17 Therefore, correlation between antifungal MIC and clinical outcome may differ in premature infants compared to older children or adults. Studies assessing Candida susceptibility and clinical outcomes are limited by small sample size, or by combining infants and adults in the same cohort.18–20 We therefore performed an analysis of data collected in the Neonatal Research Network Candida study to describe the antifungal MIC distribution for Candida in ELBW infants and to evaluate the association between antifungal resistance and death or NDI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This study included infants enrolled in the prospective NICHD-Neonatal Research Network (NRN) study, “Neonatal Candidiasis: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Clinical Judgment.”15 The objective of this former study was to identify risk factors for neonatal candidiasis. The study cohort included 1515 ELBW infants evaluated for possible sepsis between 3 and 120 days of life at 19 NRN sites from March 2004 through July 2007. In the current study, we included infants from this cohort diagnosed with IC. The Institutional Review Board at each center approved participation in the registry and the follow-up studies. Written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from parents or legal guardians.

Definitions

We defined IC as having ≥1 positive cultures for Candida from blood, urine (obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration), cerebrospinal fluid, or other sterile body source. Choice of antifungal therapy was at the discretion of the attending neonatologist and included amphotericin B deoxycholate, lipid complex amphotericin, micafungin, and fluconazole. Species were independently identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), and antifungal susceptibility testing was performed by broth microdilution according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27-A3 reference standard at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Fungus Testing Laboratory.21–23 An infant was categorized in the resistant group if he had ≥1 Candida isolate from a sterile body source that was resistant to ≥1 of the three antifungals tested. A Candida isolate was classified as resistant according to the clinical breakpoints in the CLSI M27-S4 document (Table 1).24,25 Current MIC determination methods for amphotericin B generate a restricted range of MICs, precluding reliable discrimination between susceptible and resistant Candida isolates. We therefore considered an isolate likely resistant to amphotericin B if MIC was ≥2 mg/L as suggested by the CLSI.23 There is no established fluconazole clinical breakpoint established for C. guillermondii, and no fluconazole and micafungin clinical breakpoints established for C. lusitaniae. The epidemiologic cut-off values were therefore used to identify strains with decreased susceptibility (Table 1).25–27 In addition to resistance status based on clinical breakpoints, we categorized fungal isolates as having a low or a high MIC (Table 1). The high MIC cutoff value was defined as the MIC required to inhibit 90% of a given Candida species (MIC90). For Candida species with ≤10 isolates, MIC90 could not be estimated, and the high MIC cutoff was defined as the epidemiologic cutoff value published in the literature. If an infant had multiple positive Candida cultures, the isolate with the highest MIC for a given antifungal, was used in the analysis.

Table 1.

| Species |

Low

MIC (mg/L) |

High MICa (mg/L) |

Resistance breakpoint (mg/L) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole | C.albicans | ≤0.125 | ≥0.25 | ≥8 |

| C. parapsilosis | ≤0.25 | ≥0.5 | ≥8 | |

| C. glabrata | ≤16 | ≥32 | ≥64 | |

| C. tropicalis | ≤1 | ≥2 | ≥8 | |

| C. guilliermondii | ≤4 | ≥8 | ≥8b | |

| C. lusitaniae | ≤1 | ≥2 | ≥2b | |

| Amphotericin B | All Candida species | ≤1 | ≥ 2 | ≥2c |

| Micafungin | C. albicans | ≤0.015 | ≥0.03 | ≥1 |

| C. parapsilosis, | ≤1 | ≥ 2 | ≥8 | |

| C. glabrata | ≤0.015 | ≥0.03 | ≥0.25 | |

| C. tropicalis | ≤0.06 | ≥0.12 | ≥1 | |

| C. guilliermondii | ≤1 | ≥ 2 | ≥8 | |

| C. lusitaniae | ≤0.25 | ≥ 0.5 | ≥ 0.5b |

MIC indicates minimum inhibitory concentration

Defined as the 90th percentile of MICs (MIC90) for a given Candida specie with >10 isolates, or the epidemiological cutoff value from published literature if MIC90 could not be estimated in this study.

There is no established fluconazole clinical breakpoint established for C. guillermondii, and no fluconazole and micafungin clinical breakpoints established for C. lusitaniae. The epidemiological cut-off values were therefore used to identify strains with decreased susceptibility

There is no amphotericin B clinical breakpoint established for Candida. Isolates were considered likely resistant if MIC ≥2 mg/L

The primary outcome of our analysis was the composite of death or NDI at 18–22 months of corrected age.28,29 NDI evaluation included the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) II (for infants born before 2006) or III (Table 2). Secondary outcomes included length of hospital stay and therapy failure. Therapy failure was defined for infants treated with an antifungal drug within 3 days of first positive Candida culture, as any of: 1) death within 14 days of therapy initiation, 2) end-organ involvement, and 3) persistent Candida infection defined by ≥1 positive blood or cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) cultures >14 days after therapy initiation. End-organ involvement was defined as the following: 1) at least 1 CSF positive culture for Candida, 2) ophthalmoscopy findings consistent with endophthalmitis, 3) echocardiography findings consistent with endocarditis or large sessile mass on the wall of the myocardium, and 4) echogenic findings consistent with abscesses in the liver, spleen or kidney.

Table 2.

Definition of Neurodevelopmental impairment (adapted from Wynn et al).44

| Cohort 1 (Infants born in 2004–05) |

Cohort 2 (Infants born in 2006–07) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Neurologic impairment | Moderate to severe cerebral palsy | Moderate to severe cerebral palsy |

| Development | Bayley II MDI <70 or PDI <70 | Bayley III cognitive <70 or GMFCS level ≥2 |

| Vision | Bilateral blindness with no functional vision | <20–200 bilateral |

| Hearing | Bilateral amplification for permanent hearing loss | Permanent hearing loss that does not permit the child to understand directions of examiner and communicate despite amplification |

Severe cerebral palsy defined as having a gross motor function classification system ≥2, MDI: mental development index, PDI: psychomotor development index.

Statistical Analysis

We described infants’ baseline characteristics using median and range for continuous variables, and counts and proportions for categorical variables. The proportion of infants infected with ≥1 resistant Candida was also described at the infant level for each antifungal. Candida species, distribution of MIC and proportion of resistant isolates to each antifungal were described at the isolate level. MIC50 and MIC90, defined as the MIC required to inhibit growth of 50 and 90% of the isolates for 1 given species, were described for each Candida species with >10 isolates available for analysis. We quantified variation in categorical outcomes (death or NDI, and therapy failure) related to Candida MIC (low and high; see table Supplemental Digital Content 1) and antifungal resistance, using logistic regression and adjusting for gestational age (GA) and being born before or after 2006 (cohort 1 or 2). In 2006, the Network Follow-Up study changed the psychometric instrument used to evaluate neurocognitive functioning from the BSID II to the BSID III. Among survivors, length of hospital stay was compared between infants with high MIC to any antifungal and those with only low MIC using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All statistical tests were 2-sided, with significance defined as P <0.05.

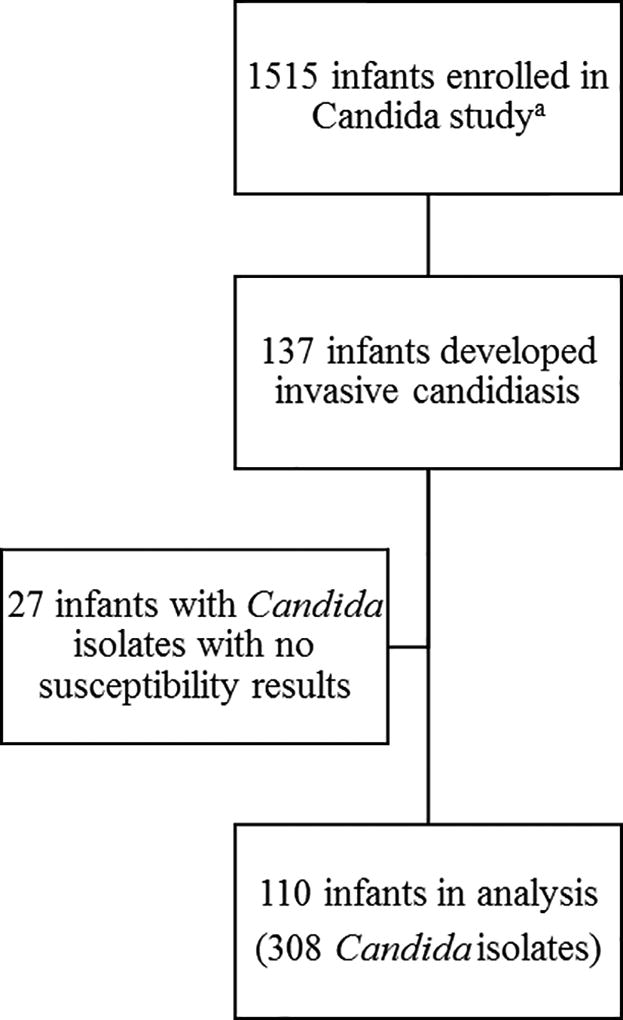

RESULTS

Among the 1515 infants enrolled, 137 (9%) developed IC, and 110/137 (80%) had MIC results (321 total Candida isolates from sterile sites) (Figure 1). Thirteen isolates were excluded from this analysis either because species identification was not successful (n=4), or Candida isolates could not be linked to a subject from the main analysis (n=9). Hence, the resulting number of Candida isolates used in this analysis was 308 from a total of 110 infants. Median (range) gestational age was 25 (23–29) weeks, and median postnatal age at first positive culture was 19 (4–84) days (see table Supplemental Digital Content 1). No difference in demographics were observed between infants with low and high MIC (see table Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Figure 1.

Study enrollment flow chart

a In the original study15

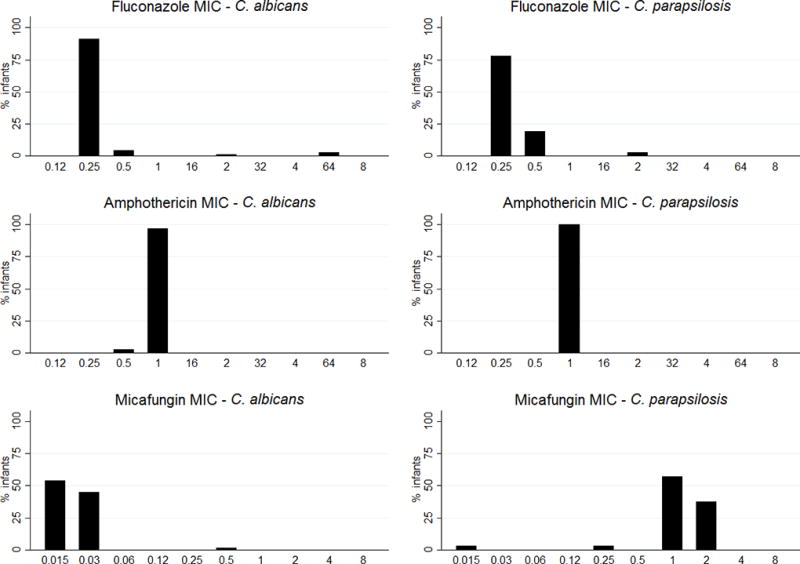

Candida species and MIC distribution

Among 308 Candida isolates, the most frequent species were C. albicans (184 [60%]), C. parapsilosis (107 [35%]), and C glabrata (9 [3%]) (Table 3). Four infants had two different Candida sp., leading to a total of 114 infant-Candida sp. Among those 114 infants-Candida sp, distribution of MIC suggested that fluconazole and amphotericin B MIC distributions were similar for C. albicans and C. parapsilosis (Figure 2). However, micafungin MIC values were higher for C. parapsilosis relative to C. albicans (Figure 2). Detailed MIC distributions for each antifungal are available in tables, Supplemental Digital Content 2–4.

Table 3.

Isolate minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC)

| Fluconazole | Amphotericin B | Micafungin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of isolates (number of infants)a, N=308 (110) |

Range MIC (mg/L) |

MIC 50/90 (mg/L) |

N, Resistant |

Range MIC (mg/L) |

MIC 50/90 (mg/L) |

N, Resistant |

Range MIC (mg/L) |

MIC 50/90 (mg/L) |

N, Resistant |

| C. albicans, n=184 (69) | 0.125 – 64 | 0.125/0.25 | 2 | 0.5 – 1 | 1/1 | 0 | 0.015 – 0.5 | 0.015/0.03 | 0 |

| C. parapsilosis, n=107 (36) | 0.125 – 2 | 0.25/0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1/1 | 0 | 0.015 – 2 | 1/2 | 0 |

| C. glabrata, n=9 (5) | 1 – 64 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 0 | 0.015 – 0.03 | - | 0 |

| C. guillermondii, n=6 (2) | 0.5 – 2 | - | 0 | 1 | - | 0 | 0.5 – 1 | - | 0 |

| C. tropicalis, n=1 (1) | 0.25 | - | 0 | 1 | - | 0 | 0.03 | - | 0 |

| C. lusitaniae, n=1 (1) | 0.5 | - | 0 | 0.5 | - | 0 | 0.25 | - | 0 |

MIC indicates the minimal inhibitory concentration; MIC 50/90 the MIC values inhibiting 50% and 90% of all Candida isolates, respectively.

4 of 110 infants are counted twice in the subject breakdown as they each tested positive for two different Candida species.

Figure 2.

Distribution of infant Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for C. albicans and C. parapsilosisa

a4 of 110 infants are counted twice in the subject breakdown as they each tested positive for two different Candida species

If an infant had multiple positive Candida cultures, the isolate with the highest MIC for a given antifungal, was used in the analysis.

All Candida isolates were susceptible to amphotericin B deoxycholate and micafungin (Table 3). Three Candida isolates (2 C. albicans, and 1 C. glabrata), each from a different infant, were resistant to fluconazole (MIC of 64 mg/L; Table 3). Those 3 infants were male, with gestational age ranging from 24 to 26 weeks, and were 5–81 days at first positive culture. None of them had received prior antifungal prophylaxis, and they were from 3 different sites.

Of the 110 infants, 46 (42%) infants had a high MIC to any antifungal. More specifically, 25 (23%), 0 (0), and 43 (39%) infants had a Candida isolate with a high MIC to fluconazole, amphotericin B deoxycholate, and micafungin, respectively. There was no significant difference in the number of infants with antifungal prophylaxis (nystatin or fluconazole), among infants with a high MIC to any antifungal (3 [7%]) versus those with only low MIC (6 [9%], p>0.73). Site proportions of Candida isolates with a high MIC to any antifungal were more variable for C. parapsilosis than for C. albicans (see figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5).

Outcomes

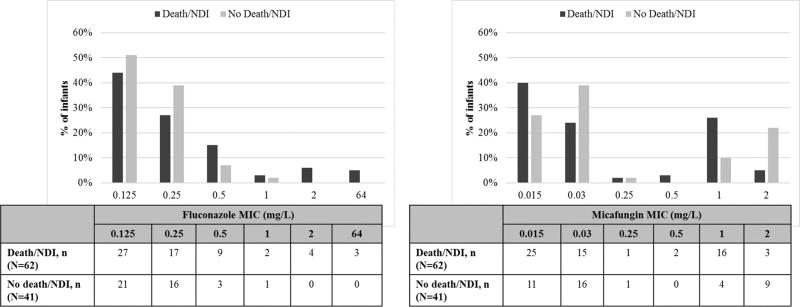

Nine infants (8%) were lost to follow-up by 18–22 months. Among the 101 infants with known status, 39 (39%) infants died by 18–22 months (Table 4A). Among 62 infants who survived, 20 (32%) had NDI; and two infants did not complete the evaluation. Among infants with complete data, 59 (60%) either died or had NDI by 18–22 months follow-up. Among infants with C. albicans and parapsilosis which are the most common species, 35 (59%) and 20 (61%) infants experienced death or NDI, respectively. All infants who had a Candida isolate with a fluconazole MIC ≥2 mg/L either died or had NDI (Figure 3). Among the 3 infants with a Candida isolate resistant to fluconazole, 2 died, while the third had NDI. Too few Candida isolates were resistant when using the clinical breakpoints (n=3) to allow the correlation between outcome and antifungal resistance. There was no significant difference in the rates of death, NDI, or death/NDI among infants with a high MIC to any antifungal, versus those with low MIC (Table 4A). This result still held after limiting the analysis to infants treated with fluconazole (Table 4B). We did not perform a subgroup analysis of clinical outcomes by micafungin MIC in the subgroup of infants who were actually treated with micafungin because of their limited number (n=8). Similarly, no subgroup analysis for amphotericin B was performed because no Candida isolates had a high MIC to that antifungal.

Table 4.

Outcomes by resistance status

| A | Invasive candidiasis (N=110) – All infants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants with Candida isolate(s)

having a low MICa (n=46) |

Infants with Candida isolate(s)

having a high MICa (n=64) |

P | |

| Death prior to discharge (%)b | 15/46 (33) | 21/64 (33) | 0.88 |

| Death at 18–22 months (%)b | 17/44 (39) | 22/57 (39) | 0.93 |

| NDI at 18-22 months(%)c | 11/25 (44) | 9/35 (26) | 0.88 |

| Death or NDI at 18–22 months (%)c | 28/42 (67) | 31/57 (54) | 0.47 |

| B | Infants with invasive candidiasis and treated with fluconazole (N=34) | ||

| Infants with Candida isolate(s) having a low fluconazole MICa (n=26) | Infants with Candida isolate(s) having a high fluconazole MICa (n=8) | P | |

| Death prior to discharge (%)b | 8/26 (31) | 2/8 (38) | 0.43 |

| Death at 18-22 months (%)b | 10/25 (40) | 3/7 (43) | 0.73 |

| NDI at 18–22 months (%)c | 3/14 (21) | 1/4 (25) | 0.57 |

| Death or NDI at 18–22 months (%)c | 13/24 (54) | 4/7 (31) | 0.27 |

| Therapy Failureb (%) | 5/25 (20) | 4/8 (50) | 0.19 |

Low and high antifungal MIC defined in Table 1

Adjusting for gestational age

Adjusting for Bayley cohort and gestational age

Figure 3.

Distribution of clinical outcomes by minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) valuea, b

NDI indicates neurodevelopment impairment; MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration

a4 of 110 infants are counted twice in the subject breakdown as they each tested positive for two different Candida species. If an infant had multiple positive Candida cultures, the isolate with the highest MIC for a given antifungal, was used in the analysis. Data on clinical outcomes missing for 11 infants.

bFigure for amphothericin B is not shown because all Candida isolates but 3 had an MIC of 1 mg/L

Among 60 infants who survived to follow-up at 18–22 months, median (range) length of hospital stay was 118 days (69–268), and median postmenstrual age at discharge was 41 weeks (37 – 65 weeks). There was no significant difference in length of stay between infants with high and low MIC, 114 days (76–268) versus 122 days (69–203), respectively, p=0.38, nor in postmenstrual age at discharge, 41 (37 – 65) weeks versus 42 (37 – 53) weeks, respectively, p=0.35. Nine (26%) out of 34 infants administered fluconazole experienced therapeutic failure. However, there was no significant difference in the rate of therapy failure between those with high versus low fluconazole MIC (Table 4B).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated antifungal susceptibility to the three most common antifungals used in the NICU in a cohort of ELBW infants infected with Candida, and determined the correlation between MIC and clinical outcome. Antifungal resistance was uncommon in this large cohort of ELBW infants with invasive candidiasis, and higher MIC did not predict clinical outcome. C. albicans and C. parapsilosis were the two most frequent species causing invasive infection (>90%) in our cohort, consistent with previous reports.2,4,6,7,18,30 Although C. glabrata was the third most frequent species, it represented only 3% of all species. This finding is consistent with previous publications in which it is significantly less frequent than in adults. 12,30

MIC distribution for amphotericin B was clustered around 1 mg/L for all species. Our results are similar to amphotericin MIC results against Candida isolates previously described in 3 cohorts of neonates in which few (0 to 8%) Candida sp from normally sterile sites had an MIC ≥2 mg/L.18,31,32 In a previous cohort of 322 premature infants (<1500g birth weight), all infecting and colonizing Candida isolates had an MIC <2 mg/L.33 The amphotericin B MIC90 we observed for C. albicans and C. parapsilosis (1 mg/L for both species) was similar to that previously described in the cohort of 322 premature infants (0.125 and 1 mg/L for infecting and colonizing isolates, respectively).34 Given that current methods for MIC determination do not reliably discriminate between Candida isolates susceptible and resistant to amphotericin B, the correlation between clinical outcome and amphotericin MIC cannot be detected.23

Fluconazole resistance was uncommon (3 [3%] infants) in this study. Previously described cohorts of premature infants have reported that no Candida isolates were resistant to fluconazole.6,31,32,34–36 This difference may be explained by the change of clinical breakpoints in 2012 for C. albicans, C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis. For these 3 species, the MIC cutoff for fluconazole resistance decreased from 64 to 8 mg/L.37,38 Previous reports of fluconazole MIC against Candida species in premature infants were usually interpreted with previous CLSI breakpoints therefore possibly underestimating fluconazole resistance.

Micafungin susceptibility data against Candida isolates in premature infants are very limited. Reports of micafungin MIC values come from mixed populations, including neonates, children and adults. In a cohort of patients (infants and adults) with C. parapsilosis fungemia (330 isolates), 2.4% of isolates were resistant to micafungin with an MIC50 and MIC90 of 1 and 2 mg/L, respectively.39 In a cohort of 200 children (0–15 years) with Candida fungemia, micafungin resistance occurred in 1% of both C. albicans, and C. parapsilosis. MIC50/90 were 0.016/0.03 mg/L and 1/2 mg/L against C. albicans, and C. parapsilosis, respectively.33 These results are similar to what we observed in our cohort of ELBW infants.

Infants with IC suffered high rates of mortality (39%) and NDI (33%). These findings were similar to previous studies of premature infants with invasive candidiasis where mortality of 22–41% and NDI incidence of 30% have been reported.8,30 Invasive infection caused by Candida isolates with high MIC may reduce antifungal efficacy and increase time to clear the pathogen from the infected site. This is all the more significant in infants with meningoencephalitis for whom antifungal penetration into the central nervous system may be insufficient against Candida species with decreased susceptibility. In the present study, the number of resistant Candida isolates was too small to detect a correlation between antifungal resistance and clinical outcome. We also analyzed outcomes by MIC, using high and low cutoff values to define susceptible ranges, but were unable to detect significant differences. Previous studies correlating in vitro susceptibility testing against Candida and clinical outcome have yielded conflicting results. In mixed cohorts including infants and adults (>90% adults) with C. albicans fungemia, all-cause 30-days mortality was increased when MIC was equal or superior to 4 mg/L.40 In another cohort including infants and adults with C. glabrata fungemia, elevated MICs were associated with clinical failure.41 Lastly, consistent with our results, data from a small, single-center study in 38 young infants failed to correlate antifungal MIC to clinical outcome in infants with candidemia.18

Our study is the first large cohort of infants <1000 g birth weight with data on resistant Candida isolates, using latest species-specific clinical breakpoints, and evaluating data on micafungin susceptibility. Limitations of this study include the lack of dosing information, and therefore we could not adjust our analysis for this important covariate. We speculate that fluconazole dosing was lower than doses currently recommended, based on PK studies published after the original NRN study.42 Another limitation is that our primary analysis focused on the correlation of outcomes and MIC to any antifungal, regardless of the antifungal (single or combined therapy) that was used for definitive treatment. However, a subgroup analysis of those treated with fluconazole did not show a correlation of fluconazole MIC and outcomes. Because there was no infant who had high amphothericin B MIC, and because of the limited number of infants who were treated with micafungin, we could not perform this analysis for those 2 antifungals. Our ability to assess fluconazole therapy failure was limited by the small number of infants with high MIC who experienced this outcome and the lack of data on central line dwell time Of note, the Bayley score used to assess NDI changed over the study period, and some experts have expressed concern that the Bayley score III (cohort 2; 2006–07) underestimates disabilities.43 However, all three infants with resistant isolates were in cohort 1, and were assessed with the Bayley score II. Finally, some infants were lost to follow-up. All these limitations may have impaired our ability to assess the effect of MIC on clinical outcome.

CONCLUSIONS

Antifungal resistance was rare among Candida isolates causing IC in ELBW infants. Infection with a Candida sp displaying high MIC was not associated with higher risk of death or NDI in this cohort of ELBW infants.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Baseline characteristicsa

Acknowledgments

We thank Annette Fothergill from University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio for her contribution to the susceptibility testing.

The National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Center for Research Resources provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s Candidiasis Study through cooperative agreements. In addition, Dr. Benjamin received support from the Thrasher Research Fund and NICHD (HD44799). While NICHD staff did have input into the study design, conduct, analysis, and manuscript drafting, the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Participating NRN sites collected data and transmitted it to RTI International, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study. One behalf of the NRN, Dr. Abhik Das (DCC Principal Investigator) had full access to all of the data in the study, and with the NRN Center Principal Investigators, take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. The list of investigators who participated in this study, in addition to those listed as authors, may be found in Supplemental Digital Content 6.

Sources of support: Supported by grants from the Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health (M01 RR30, M01 RR32, M01 RR39, M01 RR44, M01 RR54, M01 RR59, M01 RR70, M01 RR80, M01 RR633, M01 RR750, M01 RR997, M01 RR7122, M01 RR8084), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U10 HD21373, U10 HD21397, U10 HD27871, U10 HD36790, U10 HD40461, U10 HD40498, U10 HD53119, UG1 HD21364, UG1 HD21385, UG1 HD27851, UG1 HD27853, UG1 HD27856, UG1 HD27880, UG1 HD27904, UG1 HD34216, UG1 HD40492, UG1 HD40521, UG1 HD40689, UG1 HD53089, UG1 HD53109, and UG1 HD87229). The funding agency provided overall oversight for study conduct. All data analyses and interpretation were independent of the funding agencies. Dr. Benjamin also received support from the Thrasher Research Fund and NICHD (K23 HD44799).

References

- 1.Hornik CP, Fort P, Clark RH, et al. Early and late onset sepsis in very-low-birth-weight infants from a large group of neonatal intensive care units. Early human development. 2012;88(Suppl 2):S69–74. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3782(12)70019-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 Pt 1):285–291. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aliaga S, Clark RH, Laughon M, et al. Changes in the incidence of candidiasis in neonatal intensive care units. Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):236–242. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin DK, Jr, Stoll BJ, Fanaroff AA, et al. Neonatal candidiasis among extremely low birth weight infants: risk factors, mortality rates, and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 to 22 months. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):84–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotten CM, McDonald S, Stoll B, Goldberg RN, Poole K, Benjamin DK., Jr The association of third-generation cephalosporin use and invasive candidiasis in extremely low birth-weight infants. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):717–722. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healy CM, Campbell JR, Zaccaria E, Baker CJ. Fluconazole prophylaxis in extremely low birth weight neonates reduces invasive candidiasis mortality rates without emergence of fluconazole-resistant Candida species. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):703–710. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uko S, Soghier LM, Vega M, et al. Targeted short-term fluconazole prophylaxis among very low birth weight and extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1243–1252. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin DK, Jr, Hudak ML, Duara S, et al. Effect of fluconazole prophylaxis on candidiasis and mortality in premature infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(17):1742–1749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams-Chapman I, Bann CM, Das A, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants with Candida infection. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4) doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.034. 961-967.e963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):503–535. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goel N, Ranjan PK, Aggarwal R, Chaudhary U, Sanjeev N. Emergence of nonalbicans Candida in neonatal septicemia and antifungal susceptibility: experience from a tertiary care center. J Lab Physicians. 2009;1(2):53–55. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.59699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfaller MA, Andes D, Diekema DJ, Espinel-Ingroff A, Sheehan D. Wild-type MIC distributions, epidemiological cutoff values and species-specific clinical breakpoints for fluconazole and Candida: time for harmonization of CLSI and EUCAST broth microdilution methods. Drug Resist Updat. 2010;13(6):180–195. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Sheehan DJ. Interpretive breakpoints for fluconazole and Candida revisited: a blueprint for the future of antifungal susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(2):435–447. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.435-447.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wade KC, Wu D, Kaufman DA, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in young infants. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2008;52(11):4043–4049. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00569-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamin DK, Jr, Stoll BJ, Gantz MG, et al. Neonatal candidiasis: epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical judgment. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):e865–873. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez M, Moylett EH, Noyola DE, Baker CJ. Candidal meningitis in neonates: a 10-year review. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(2):458–463. doi: 10.1086/313973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman S, Richardson SE, Jacobs SE, O'Brien K. Systemic Candida infection in extremely low birth weight infants: short term morbidity and long term neurodevelopmental outcome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(6):499–504. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200006000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang YC, Kao HT, Lin TY, Kuo AJ. Antifungal susceptibility testing and the correlation with clinical outcome in neonatal candidemia. American journal of perinatology. 2001;18(3):141–146. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-14524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovacicova G, Krupova Y, Lovaszova M, et al. Antifungal susceptibility of 262 bloodstream yeast isolates from a mixed cancer and non-cancer patient population: is there a correlation between in-vitro resistance to fluconazole and the outcome of fungemia? Journal of infection and chemotherapy : official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2000;6(4):216–221. doi: 10.1007/s101560070006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park BJ, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Hajjeh RA, et al. Evaluation of amphotericin B interpretive breakpoints for Candida bloodstream isolates by correlation with therapeutic outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(4):1287–1292. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1287-1292.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westblade LF, Jennemann R, Branda JA, et al. Multicenter study evaluating the Vitek MS system for identification of medically important yeasts. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2013;51(7):2267–2272. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00680-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iriart X, Lavergne RA, Fillaux J, et al. Routine identification of medical fungi by the new Vitek MS matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight system with a new time-effective strategy. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2012;50(6):2107–2110. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06713-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CLSI. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; Approved standard - Third Edition (CLSI Document M27-A3) Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 24.CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Fourth Informational Supplement (CLSI document M27-S4) Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Andes D, et al. Clinical breakpoints for the echinocandins and Candida revisited: integration of molecular, clinical, and microbiological data to arrive at species-specific interpretive criteria. Drug Resist Updat. 2011;14(3):164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaller MA, Castanheira M, Diekema DJ, Messer SA, Jones RN. Triazole and echinocandin MIC distributions with epidemiological cutoff values for differentiation of wild-type strains from non-wild-type strains of six uncommon species of Candida. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2011;49(11):3800–3804. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05047-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Procop GW, Rinaldi MG. Comparison of the Vitek 2 yeast susceptibility system with CLSI microdilution for antifungal susceptibility testing of fluconazole and voriconazole against Candida spp., using new clinical breakpoints and epidemiological cutoff values. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayley N. In: Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. Second. Corporation TP, editor. San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bayley N. In: Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. Third. Corporation TP, editor. San Antonio, TX: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blyth CC, Chen SC, Slavin MA, et al. Not just little adults: candidemia epidemiology, molecular characterization, and antifungal susceptibility in neonatal and pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):1360–1368. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ben Abdeljelil J, Saghrouni F, Nouri S, et al. Neonatal invasive candidiasis in Tunisian hospital: incidence, risk factors, distribution of species and antifungal susceptibility. Mycoses. 2012;55(6):493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roilides E, Farmaki E, Evdoridou J, et al. Neonatal candidiasis: analysis of epidemiology, drug susceptibility, and molecular typing of causative isolates. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23(10):745–750. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peman J, Canton E, Linares-Sicilia MJ, et al. Epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility of bloodstream fungal isolates in pediatric patients: a Spanish multicenter prospective survey. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2011;49(12):4158–4163. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05474-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manzoni P, Stolfi I, Pugni L, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of prophylactic fluconazole in preterm neonates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(24):2483–2495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertini G, Perugi S, Dani C, Filippi L, Pratesi S, Rubaltelli FF. Fluconazole prophylaxis prevents invasive fungal infection in high-risk, very low birth weight infants. The Journal of pediatrics. 2005;147(2):162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaufman D, Boyle R, Hazen KC, Patrie JT, Robinson M, Donowitz LG. Fluconazole prophylaxis against fungal colonization and infection in preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(23):1660–1666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CLSI. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; Fourth Informational Supplement. M27-S4 Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 2012;32(17):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fothergill AW, Sutton DA, McCarthy DI, Wiederhold NP. Impact of new antifungal breakpoints on antifungal resistance in Candida species. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2014;52(3):994–997. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03044-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canton E, Peman J, Quindos G, et al. Prospective multicenter study of the epidemiology, molecular identification, and antifungal susceptibility of Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis isolated from patients with candidemia. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2011;55(12):5590–5596. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00466-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Hal SJ, Chen SC, Sorrell TC, Ellis DH, Slavin M, Marriott DM. Support for the EUCAST and revised CLSI fluconazole clinical breakpoints by Sensititre(R) YeastOne(R) for Candida albicans: a prospective observational cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014 doi: 10.1093/jac/dku124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexander BD, Johnson MD, Pfeiffer CD, et al. Increasing echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata: clinical failure correlates with presence of FKS mutations and elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(12):1724–1732. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wade KC, Benjamin DK, Jr, Kaufman DA, et al. Fluconazole dosing for the prevention or treatment of invasive candidiasis in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(8):717–723. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819f1f50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson PJ, De Luca CR, Hutchinson E, Roberts G, Doyle LW. Underestimation of developmental delay by the new Bayley-III Scale. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2010;164(4):352–356. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wynn JL, Tan S, Gantz MG, et al. Outcomes following candiduria in extremely low birth weight infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(3):331–339. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Baseline characteristicsa