Abstract

Objective

Wisdom is a complex trait, and previous research has identified several components of wisdom. This study explored the possible impact of a diagnosis of a terminal illness on conceptualization and evolution of wisdom while facing the end of life.

Design and Participants

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with 21 hospice patients aged 58–97 who were in the last six months of their life.

Methods

Hospice patients were asked to describe the core characteristics of wisdom, as well as how their terminal illness might have impacted their understanding of this concept. The interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and coded by the research team using a grounded theory analytic approach based on coding consensus, co-occurrence, and comparison.

Results

Broad concepts of wisdom described by the hospice patients align with the extant literature, thereby supporting those general conceptualizations. In addition, hospice patients described how their life perspectives shifted after being diagnosed with a terminal illness. Post-illness wisdom can be characterized as a dynamic balance of actively accepting the situation while simultaneously striving for galvanized growth. This delicate tension motivated the patients to live each day fully, yet consciously plan for their final legacy.

Conclusion

The end of life offers a unique perspective on wisdom by highlighting the modulation between actively accepting the current situation while continuing the desire to grow and change at this critical time. This paradox, when embraced, may lead to even greater wisdom while facing one’s own mortality.

Keywords: palliative care, cancer, spirituality, resilience

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

— Søren Kierkegaard, Philosopher (1843)

INTRODUCTION

While wisdom is an ancient religious and philosophical concept (Takahashi, 2000; Jeste & Vahia, 2008), one of the first modern scientists to consider wisdom as a psychological construct was Erikson (Erikson, 1950). He described foundational stages of psychosocial development, with the final (eighth) stage being characterized by a conflict between ego integrity and despair; the optimal resolution of this stage was acquisition of wisdom. Empirical research on wisdom began in the 1970s and has been growing in recent years (Baltes & Smith, 2008; Clayton, 1975). Modern conceptualizations describe wisdom as an aggregate and inter-related mix of cognitive, affective, and reflective attributes (Ardelt, 2004; Sternberg, 1990; Thomas et al., 2017).

To develop a consensus definition of wisdom based on the published literature, Bangen et al. (2013) conducted a meta-review utilizing cohorts ranging from adolescence (Damon, 2000; Lerner, 2008; Pasupathi, Staudinger, & Baltes, 2001) to older adulthood (Glück et al., 2005; Happé et al., 1998; Smith & Baltes, 1990). The review integrated conceptualizations from 24 empirical definitions across 31 articles, and identified nine distinct components of wisdom, listed in decreasing order of frequency of citations in published definitions: 1) social decision making and general knowledge of life, 2) prosocial attitudes and behaviors, 3) reflection and self-understanding, 4) acknowledgement of uncertainty, 5) emotional regulation, 6) value relativism and tolerance, 7) openness to new experience, 8) spirituality and religiosity, and 9) sense of humor.

Although this meta-review provided cohesion for wisdom conceptualizations, the concept of wisdom may vary somewhat, depending on age-based, cultural, contextual, historical, philosophical, or religious lenses used to investigate the construct (Kross & Grossmann, 2012)(Jeste & Vahia, 2008; Takahashi, 2000). In terms of lifespan, hospice care has been redefining our understanding of the affective, cognitive, physical, social, and spiritual underpinnings of well-being as death draws near (Murray et al., 2007; Pinder & Hayslip Jr., 1981; Vachon et al., 2009). Most notably, it has been suggested that the end of life can provide a unique time for possible self-transcendence and self-reflection (Vachon et al., 2009), constructs often associated with the presence of intelligence, spirituality, and wisdom (Jeste et al., 2010). Facing mortality is thought to evoke a greater awareness about larger life perspectives (Bellizzi, 2004), and a dynamic relationship can exist between positive and negative life experiences at this stage (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999; Diamond & Aspinwall, 2003; Meier, et al., 2016). Therefore, assessing individuals at the end of their lives may be particularly salient for characterizing and understanding their perspectives on wisdom.

To explore this possibility, we qualitatively interviewed patients who were diagnosed with a terminal illness and receiving hospice care during the last six months of their life. We examined their reflections regarding the characteristics and influences of wisdom. The study aimed to understand whether a hospice cohort could offer a distinct perspective on wisdom, given their potential to uniquely reflect back on life, coupled with their current understanding of how to live life when faced with a terminal illness.

METHODS

Procedures for data collection and analysis were reviewed and approved by the Human Research Protections Program at the University of California San Diego, USA. Informed consent was obtained from each hospice patient after the study objectives had been fully explained.

Patients were recruited by members of their hospice team with informational study brochures. The study inclusion criteria were purposely broad, given the novel and exploratory nature of this research: all hospice patients who were English speaking and able to complete a one-hour interview were eligible to participate. Study recruitment remained open until the data evidenced theoretical saturation (Morse, 1995).

After study enrollment, each patient completed an individual, 60-minute, semi-structured interview with a mental health professional working in hospice care. All the interviews were audiotaped and conducted in the patients’ homes or residences. The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide, which included questions regarding the descriptions and characteristics of wisdom as well as life influences on wisdom. Primary questions in the interviews included: “How do you define wisdom?”; “What are the characteristics of wise people, in your opinion?”; “What experiences have influenced your level of wisdom?” and “How has your illness affected your level of wisdom?” Notably, all the interviews were open-ended to allow patients to introduce or expand upon topics of importance to them, and to allow for additional follow-up questions, as needed, to learn more about each patient’s unique perspective.

Upon completion of the interviews, each audiotape was transcribed, providing a total of 236 pages for analysis (the average patient interview was 11.2 pages in length). These transcripts reflected the content of the interviews verbatim, thereby allowing reviewers to code the content in full. Based within the methodology of “Coding Consensus, Co-occurrence, and Comparison” as outlined by Willms et al. (1990), the interview transcripts were analyzed using a grounded theory analytic approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

First, approximately one-quarter (24%, n=5) of the interviews were randomly selected for coding by the first and second authors. This coding was completed at a general level by identifying common words or phrases seen in the interviews, in order to condense the data into analyzable units. Paragraphs within each interview were assigned open and axial codes based on a priori (i.e., questions in the interview guide) or emergent themes (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In many instances, the same paragraph was assigned multiple codes. These initial codes were provided to the full research team. Disagreements in assignments or descriptions of codes were resolved through a discussion among all the study authors and a final coding matrix was created.

Next, the first and second authors independently coded all 21 interviews in their entirety using the agreed-upon coding matrix. These two authors then reviewed all the codes proposed, and discussed whether they agreed or disagreed with each of the codes as chosen by the other. Comparison of codes assigned to one of the transcripts revealed an inter-rater reliability rate of 96% – a level indicating high concordance between coders (Boyatzis, 1998).

Finally, all of the codes were entered into Dedoose, a computer program designed for qualitative and mixed-methods analyses (Dedoose, 2015). Using the method of constant comparison (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), codes were then grouped into broader themes, and provided the basis for a group discussion among all the authors regarding the thematic salience and ensuing conceptual map of themes.

RESULTS

Participants

Twenty-one patients diagnosed with a terminal illness, who had a prognosis of six months or less to live, were enrolled in the study between 2012 and 2015. The patients were receiving care at either San Diego Hospice or Mission Hospice, both located in San Diego, California, USA. Patient ages ranged from 58 to 97 years, with a mean age of 78 (SD = 11). A majority of the patients were Caucasian (81%, n=17), and approximately one-half were male (57%, n=12), Christian (48%, n=10), and diagnosed with cancer (48%, n=10). The remaining diagnoses included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, pulmonary fibrosis, and end-stage liver disease. Most study patients were either widowed (38%, n=8) or currently married (33%, n=7).

Descriptions and Characteristics of Wisdom

In response to open-ended questions regarding general characteristics of wisdom, patients spontaneously discussed each of the nine components of wisdom as previously identified in the meta-review by Bangen et al. (2013), thereby supporting the review’s overall findings. However, the order of thematic salience of individual components for this hospice sample (Table 1) differed from that based on salience in the published literature (given above in the Introduction). For hospice patients, the order was: 1) prosocial attitudes and behaviors, 2) social decision making and general knowledge of life, 3) emotional regulation, 4) openness to new experience, 5) acknowledgment of uncertainty, 6) spirituality and religiosity, 7) reflection and self-understanding, 8) sense of humor, and 9) value relativism and tolerance. See Table 1 for exemplar patient quotes related to each general theme.

Table 1.

Emergent Themes Reported by 21 Hospice Patients Regarding General Descriptions and Characteristics of Wisdom

| Emergent Theme | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|

| Prosocial Attitudes and Behaviors |

“I think you would have more wisdom if you have empathy and compassion. Because with empathy and compassion, comes understanding.” “I’ve never seen anybody who is self-centered who I can say is wise.” |

| Social Decision Making and General Knowledge of Life |

“I think a wise person goes and seeks counsel and looks for information before they just jump in and make a decision… They weigh the consequences and the pros and the cons.” “Wise people, in my opinion, will think a great deal before they make any judgments.” |

| Emotional Regulation |

“I think many times your emotions and personal problems can get in the way of being wise.” “Every day is a living experience, and it is what you can make of it, whether it is going to be a happy day or not. What you allow into your life makes you happy or sad.” |

| Openness to New Experience |

“Wisdom is knowledge learned by your mistakes and the action you take to correct those mistakes.” “Keep involved with things. Keep your eyes open, your ears open, study, learn all you can about every subject, and do not stop. Maybe then you will be wise…” “I think that’s how we gain wisdom - by experience and observation and having an open mind to everything that comes along.” |

| Acknowledgement of Uncertainty |

“There is no way to know it all, that’s the whole problem. You don’t know it all. Nobody will, and I think maybe that’s wisdom in itself - realizing that you don’t know anything.” “Wisdom means seeing life on life’s terms.” “The last and final life-changing event was being diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer, that was inoperable and basically terminal. I don’t know how long, but it’s gonna be one of the things where I’m gonna live for as long as I can… I am looking forward to taking whatever God’s given me, whatever I have to use for rest of my life - then I will leave it.” |

| Spirituality and Religiosity |

“I ask for wisdom… I have a relationship with God, and if I need something, I ask Him.” “To me, wisdom is not from man. I get my knowledge and understanding from above.” “I feel I’m wise every time I let go and surrender my little ego self; all you really have to do is plant the seed, and then get out of the way and let the universe produce for you.” |

| Reflection and Self-Understanding |

“Start getting to know yourself… Because everything you’re ever gonna need, you’ve already got.” “Wisdom is the inner voice that we’re given at birth… but most people seem to seek exterior forces and people, places, and things in order to make them happier, but to me wisdom itself emanates from within us, we just have to slow down long enough to find it.” |

| Sense of Humor | “There is usually humor in a lot of things although there is sadness too. You cannot listen to that sadness. You have to get out of it, or you get so depressed, you know. Then you are not good to anyone and you are absolutely useless to yourself.” |

| Value Relativism and Tolerance | “I think the characteristics of wise people are people who listen. They are good listeners… and they aren’t judgmental. They are willing and open to listening to all sides before they say anything.” |

Note: Themes listed in order of thematic salience based on the hospice patients’ interviews. Themes compared to the components of wisdom as described in the meta-review by Bangen et al (2013).

Influences of Illness on Wisdom

Impact of Illness and Receiving Hospice Care

In addition to the general conceptualizations of wisdom presented above, the hospice patients in this sample were able to provide additional unique insights into how wisdom may build or transform after being diagnosed with a terminal illness. These shifts were not necessarily changes the patients had intentionally cultivated. Instead they described dramatic shifts that occurred in a relatively short time frame, and ones that were directly linked to being seriously ill and/or initiating hospice care.

“I think I have learned wisdom, but I did not learn it from home. I have learned most of it from being in the situation I am in now, really. I never thought about it before. It was just, you know… I was doing my own thing and everything was fine. Then you get to a point where you cannot do it anymore, and the wisdom comes in learning how to handle the situation you are in.”

“I really did not have to think about wisdom before I was ill.”

“I guess that’s the last experience that I’ve had to deal with. My perspective, my outlook on life - my outlook on everything - has changed. It’s grown tremendously.”

Active Acceptance

Patients described their hope of finding a sense of acceptance or peace related to their illness, particularly in light of their ensuing physical changes and loss of functioning. This theme was not described as a passive “giving up,” but as an active coping process. Here patients emphasized appreciating life, taking the time to reflect, and even finding ways to live more simply than before they became ill. There was also a keen sense of fully enjoying the time they had left and in so doing, finding the beauty in everyday life.

“For all my life, being a Southerner and having been in beauty contests, I got up in the morning, put my full makeup on, and did my hair every day. A lady was never in her night gown unless she was giving birth! Now all that is very, very difficult for me and I think that has been really hard. I’ve accepted it, and I realized that I have to let it go. I have to ask for help and allow them to help me. I try to take all this with as much graciousness as possible - which I’ve learned is more important anyway. And I realized that my friends really don’t care. They don’t care that I don’t have makeup on or I’m in my night gown. They are just happy to see me out of bed sitting on a chair.”

“Well, I do not think I am the wisest person, but now I think wisdom is about cultivating a happy attitude in your life. Not necessarily based on having money, but being happy with just looking at the sky and appreciating nature and loving the people around you. I think then you will have a very rich life.”

“Unfortunately, my body does not keep up with my mind. I’m limited in the things I’d like to do and want to do, but at the same time you have to make adjustments. I mean, I used to be an avid tennis player and hiking was a part of my life. I’ve had to say, ‘Well that’s behind you.’ I am very fortunate to have a daughter and a wife who take me out places and who take me to watch the seagulls at sunset.”

“Hmmm…what has changed? Well, one thing is that I have no interest in money. Money used to be pretty important… I always thinking ‘What could I buy?’ or ‘What could I do?’ I am not that way anymore. Nothing material is important since I have been on hospice.”

“I know when I moved here it was the best decision I could have made. It was a painful one and then I realized it was a wise decision to stop treatment. I made the decision before it had to be made for me. You can spin your wheels and go from doctor to doctor looking for hundreds of different treatments… But there comes a day when you have to accept the fact that everything that can be done has been done.”

Galvanized Growth

Patients also spoke of positive changes they encountered in response to their illness. These adaptive characteristics were stimulated and forged by the difficulty of living with a terminal illness, and this galvanizing process was linked directly to increase in wisdom. For example, most patients talked about finding increased determination, gratitude, positivity, and strength. Patients further noted increases in spiritual or religious practices as they connected to these evolving aspects of themselves.

“Every day I wake up and I am alive, I am thankful. I do not take it for granted. I did before I got sick - but not now.”

“I think I’m a little stronger in my life. When you are with the disease, it makes you have a lot of patience.”

“I think I know more about people; people’s reactions, what people are really striving for, and the importance of goals and things that I did not even think about before.”

“I say to the Lord when I wake up in the morning, ‘My God, thank you for giving me my new life.’ Because when you get up in the morning, it is a new life. Someday I will not get up no more.”

“Now wisdom is being aware of my surroundings, trying to read the people that I meet, and trying to appreciate my day and look for the gifts. Look for the positive instead of the negative, I would say.”

Wisdom Involves Persistent and Dynamic Balance

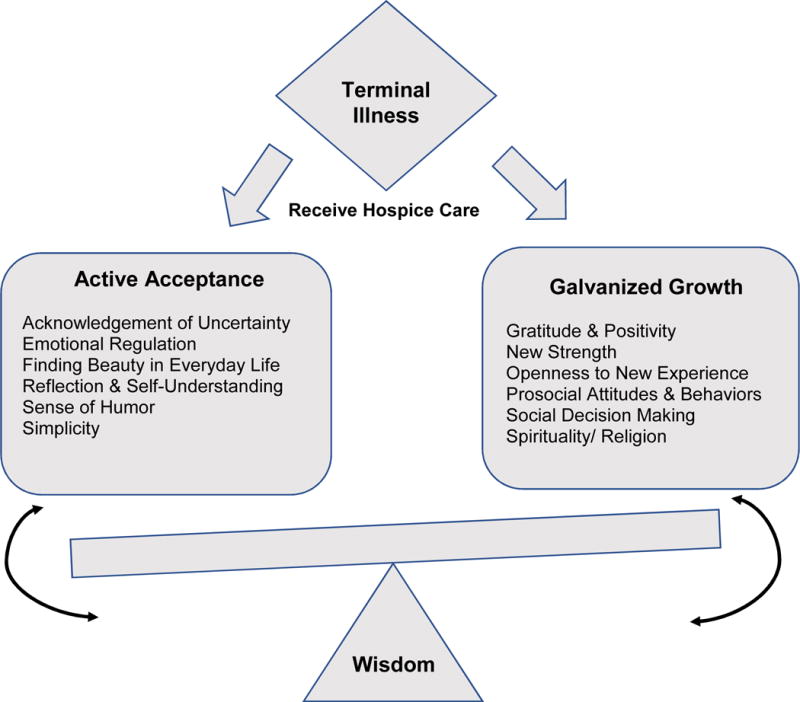

Ultimately, patients described wisdom as a perpetual balance between actively accepting illness on one hand, while wanting to grow and change on the other (see Figure 1 for a conceptual model). Contentment was seen when both sides of the “seesaw” experience were acknowledged, with an understanding that on some days the seesaw forgivably tipped more to one side than the other. There was no “perfect” solution in the face of illness, but rather on-going vacillations between learning to accept things as they were versus striving to change. For patients, wisdom involved honestly recognizing this struggle and humbly allowing it to exist. This process often led to clearer intentions about how the patients wanted to live during their remaining days, with a sense of gravitas for how those final days would directly reflect their life’s legacy.

“I started a new business, kept that going, and then I guess the last and final life-changing event was being diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer - inoperable and basically terminal. I’m working on living as long as I can, but the point is that I am looking forward to taking whatever God has given me, whatever I have during the rest of my life, then I will leave it.”

“I’ve got three more treatments, then we’re gonna do the testing and all of that. We will see how it all works up. But whatever way it works, it’s just gonna work out the way it is supposed to. I’ll do what I can.”

“I had to learn how to do nothing – I went from a person that did everything to a person that does nothing. It takes more wisdom than I had. I have it now because I have learned how to cope with it, and I am more comfortable with my situation. Not 100%, but more comfortable.”

“Well, right now, I could just sit around and feel sorry for myself and not do anything at all. And what a waste that would be at the end of my life.”

“I want them to remember me with a smile, laughing and giggling and doing some of the silly things we do. You know, it is fun. Why do you want to leave on a sad note? I do not want to be remembered being sad.”

“You know I’m terminal. When I came in, they said there will be two or three weeks… it has been six weeks, and now it is getting to the point where my ability to swallow is gone; it should happen today or tomorrow. I know I’m going {to die} and this is wisdom. I’m not going to worry about whether I chose the right thing to do, or whether my life was good enough. I know I’m going… and I don’t fear.”

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Wisdom as Qualitatively Described by Patients Receiving Hospice Care at the End of Their Life (n=21)

DISCUSSION

This study offers a unique perspective on wisdom from patients receiving hospice care at the end of their lives, thereby contributing to previous conceptualizations of wisdom’s cognitive, reflective, and affective origins (Ardelt, 2004; Clayton & Birren, 1980; Thomas et al., 2017). There are several similarities between the themes discussed by this hospice sample and those previously reported in the literature. Specifically, nine of the subcomponents of wisdom spontaneously described by these hospice patients were similar to those outlined in the meta-review by Bangen et al. (2013); however, the order of salience was different. Thus, compared to the frequency of citations in the published papers, the dying patients ranked emotional regulation, openness to new experience, and spirituality higher, whereas reflection and self-understanding, and value relativism and tolerance were ranked lower.

Patients in this study explained the nuances of how receiving a terminal illness and entering hospice care changed their overall perspective, how they strived to actively accept their new situation, and how they found a refined sense of galvanized growth in the process. These patients also shed new light on how wisdom involved a delicate balance between learning to simply be, while continually striving to change. Hospice staff may be familiar with how patients seem to “seesaw” in this regard. On some days, patients may appear very accepting of their life circumstances, while on others they seem fraught with struggle. This same process may be mirrored in the actions of patients’ loved ones, and may even be seen among staff as they aim to actively accept patients’ mortality, yet simultaneously work hard to improve the lives of the patients and their families on a daily basis (Meier et al., 2016).

In some respects, perhaps this “seesaw” concept is similar to the balance described in the Serenity Prayer: “Lord, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference” (Niebuhr, 2015). In its simplicity, this prayer highlights the dynamic and dualistic nature of wisdom as described by the hospice patients in this study. They too conveyed a pervasive battle that, when paradoxically embraced, could lead to contentment - even when the worst of life or death is placed before us.

Finally, the hospice patients in this study noted how their struggles related to conscious decisions about the attitudes and behaviors they wished to express in their final days. The patients understood that their final actions would impact their legacy. This finding speaks directly to the importance of not only providing dignity in care, but also ensuring that legacy-related needs of patients are addressed (Chochinov, 2007). In sum, the hospice patients in this study highlighted how, after being diagnosed with a terminal illness, one’s life perspective shifts. One may learn to accept the illness, but may also wisely strive for growth at the same time. This tension can catalyze the need to live each day fully, and by doing so, can leave an even greater legacy.

Although beneficial in understanding perspectives on wisdom among adults in hospice care, this study does have limitations. First, all the subjects were drawn from a sample in San Diego, California, and the majority of patients were Caucasian (81%). Although this percentage mirrors 2014 national statistics with approximately 76% of all hospice patients in the United States being Caucasian (NHPCO Facts and Figures, 2015), it leaves unanswered questions about how a more geographically, ethnically, and racially diverse group of patients might describe wisdom at the end of their lives.

Additionally, because this study required a 60-minute interview, patients with serious cognitive or other psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., major depressive disorder) were not likely to participate. As a result, the components of wisdom found in this study such as active coping and galvanized growth need to be further evaluated within other clinical populations. Finally, the one-time qualitative interview was conducted among patients who were receiving hospice care and, by definition, were in the last six months of life. As a result, all the patients are now deceased, thereby barring any follow-up assessments.

Overall, these study findings suggest that interviewing hospice patients might hold value for understanding not only the concept of wisdom, but other important concepts as well (Morley, 2004). For example, hospice patients may help us refine other conceptualizations about aging, illness, love, loss, or even grace in the face of death (Depp & Jeste, 2006; Montross Thomas, 2015). Perhaps those living in the last six months of their life could provide an unparalleled and exquisite window into what it means to truly “be alive.”

“In the last analysis, it is our conception of death which decides our answers to all the questions life puts to us.”

— Dag Hammarskjöld, former Secretary-General of the United Nations (1964).

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the courage and commitment of the hospice patients who elected to share their thoughts and reflections as they approached the end of their lives. To them, we are inherently and respectfully grateful. We further wish to acknowledge all the dedicated individuals at Mission Hospice and the San Diego Hospice who were devoted to this study’s purpose, design, and completion.

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health, Grant R25 MH071544/MH/NIMH, the NIMH-funded T32 Geriatric Mental Health Program MH019934, and the Sam and Rose Stein Institute for Research on Aging at University of California San Diego (PI: Dilip V. Jeste, M.D.) Additional staff time and support were provided by the American Cancer Society 124667-MRSG-13-233-01-PCSM, the Westreich Foundation, and the MAPI Research Trust (PI: Lori P. Montross-Thomas, Ph.D.).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this report.

References

- Ardelt M. Wisdom as expert knowledge system: A critical review of a contemporary operationalization of an ancient concept. Human development. 2004;47(5):257–285. doi: 10.1159/000079154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Smith J. The fascination of wisdom: Its nature, ontogeny, and function. Perspectives on psychological science. 2008;3(1):56–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangen KJ, Meeks TW, Jeste DV. Defining and assessing wisdom: a review of the literature. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(12):1254–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi KM. Expressions of generativity and posttraumatic growth in adult cancer survivors. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2004;58(4):267–287. doi: 10.2190/DC07-CPVW-4UVE-5GK0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. London and New Delhi: Sage Publications; 1998. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz D, Charles ST. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54:165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov HM. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A,B,C, and D of dignity conserving care. BMJ. 2007;334:184–197. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39244.650926.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton V. Erikson’s theory of human development as it applies to the aged: Wisdom as contradictive cognition. Human development. 1975;18(1-2):119–128. doi: 10.1159/000271479. (No DOI) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon W. Understanding wisdom: Sources, science, and society. Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press; 2000. Setting the stage for the development of wisdom: Self-understanding and moral identity during adolescence; pp. 339–360. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose. Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2015. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Aspinwall LG. Emotion regulation across the life span: An integrative perspective emphasizing self-regulation, positive affect, and dyadic processes. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27(2):125–156. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM. Reflection, perception and the acquisition of wisdom. Medical Education. 2008;42(11):1048–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Norton [WMS] 1950. Childhood and society, revised 1963. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldrine Publishing Company; 1967. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Glück J, Bluck S, Baron J, McAdams DP. The wisdom of experience: Autobiographical narratives across adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29(3):197–208. doi: 10.1177/01650250444000504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarskjöld D, Auden WH, Sjöberg L. In: Markings [“Vägmärken”] by Dag Hammarskjöld. Sjöberg Leif, Auden WH., translators. Faber & Faber; 1964. with a Foreword by WH Auden. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Happé FGE, Winner E, Brownell H. The getting of wisdom: theory of mind in old age. Developmental psychology. 1998;34(2):358–362. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.2.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Ardelt M, Blazer D, Kraemer HC, Vaillant G, Meeks TW. Expert consensus on characteristics of wisdom: A Delphi method study. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(5):668–680. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Vahia IV. Comparison of the conceptualization of wisdom in ancient Indian literature with modern views: focus on the Bhagavad Gita. Psychiatry. 2008;71(3):197209. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierkegaard S. Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol. 18. Copenhagen: Søren Kierkegaard Research Center; 1843. Journalen JJ; p. 306. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Kross E, Grossmann I. Boosting wisdom: Distance from the self enhances wise reasoning, attitudes, and behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2012;141(1):43–48. doi: 10.1037/a0024158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM. Spirituality, positive purpose, wisdom, and positive development in adolescence: Comments on Oman, Flinders, and Thoresen’s ideas about “Integrating spiritual modeling into education”. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2008;18(2):108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Meier E, Gallegos JV, Thomas LP, Depp CA, Irwin SA, Jeste DV. Defining a good death (successful dying): Literature review and a call for research and public dialogue. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;24(4):261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.01.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montross-Thomas LP. What Are the Most Loving Moments of Your Life? Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015;18(5):398. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0006.18.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE. The top 10 hot topics in aging. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2004;59(1):M24–M33. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.1.M24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. The significance of saturation. Qualitative health research. 1995;5(2):147–149. doi: 10.1177/104973239500500201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Grant E, Boyd K, Barclay S, Sheikh A. Patterns of social, psychological, and spiritual decline toward the end of life in lung cancer and heart failure. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2007;34(4):393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHPCO. Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. Vol. 2016. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; 2015. p. 7. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Niebuhr R. Major works on religion and politics. In: Sifton E, editor. The Library of America. New York, NY: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc; 2015. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M, Staudinger UM, Baltes PB. Seeds of wisdom: adolescents’ knowledge and judgment about difficult life problems. Developmental psychology. 2001;37(3):351–361. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder MM, Hayslip B., Jr Cognitive, attitudinal, and affective aspects of death and dying in adulthood: Implications for care providers. Educational Gerontology: An International Quarterly. 1981;6(2–3):107–123. doi: 10.1080/0380127810060201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Baltes PB. Wisdom-related knowledge: Age/cohort differences in response to life-planning problems. Developmental psychology. 1990;26(3):494. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.26.3.494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg RJ. Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development. Cambridge University Press; 1990. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. (No DOI) [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M. Toward a culturally inclusive understanding of wisdom: historical roots in the East and West. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2000;51(3):217–230. doi: 10.2190/H45U-M17W-3AG5-TA49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas ML, Bangen KJ, Palmer BW, Sirkin A, Avanzino JA, Depp CA, Glorioso D, Daly RE, Jeste DV. A new scale for assessing wisdom based on common domains and a neurobiological model: The San Diego Wisdom Scale (SD-WISE) Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachon M, Fillion L, Achille M. A conceptual analysis of spirituality at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(1):53–59. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willms DG, Best JA, Taylor DW, Gilbert JR, Wilson D, Lindsay EA, Singer J. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1990;4(4):391–409. doi: 10.1525/maq.1990.4.4.02a00020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]