Abstract

22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) is associated with high rates of anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, and other psychiatric conditions. In the general population, psychiatric disorders are treated with proven pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). To begin to assess the feasibility and efficacy of non-pharmacological therapies in 22q11.2DS, we performed a systematic search to identify literature on non-pharmacological interventions for psychiatric disorders in individuals with 22q11.2DS. Of 1,240 individual publications up to mid-2016 initially identified, 11 met inclusion criteria. There were five literature reviews, five publications reporting original research (two originating from a single study), and one publication not fitting either category that suggested adaptations to an intervention without providing scientific evidence. None of the original research involved direct study of the evidence-based non-pharmacological therapies available for psychiatric disorders. Rather, these four studies involved computer-based or group interventions aimed at improving neuropsychological deficits that may be associated with psychiatric disorders. Although the sample sizes were relatively small (maximum 28 participants in the intervention group), these reports documented the promising feasibility of these interventions, and improvements in domains of neuropsychological functioning, including working memory, attention, and social cognition. The results of this review underline the need for research into the feasibility and efficacy of non-pharmacological treatments of psychiatric disorders in individuals with 22q11.2DS to inform clinical care, using larger samples, and optimally, standard randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trials methodology.

Keywords: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, non-pharmacological treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychiatric disorder

INTRODUCTION

22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) is the most common microdeletion syndrome in humans, estimated to affect up to 1 in 2,000 live births (Fung et al. 2015; McDonald-McGinn et al. 2015; Bassett et al. 2011). This condition is typically a multisystem disorder, and major features include an array of somatic and neuropsychiatric disorders (Fung et al. 2015; McDonald-McGinn et al. 2015; Bassett et al. 2011). Prominent features include congenital anomalies, endocrine disorders, intellectual and developmental disabilities, and early- and later onset psychiatric conditions. Three in five adults with the syndrome will develop one or more psychiatric disorders in their lifetime (Fung et al. 2010). More specifically, anxiety disorders are reported in approximately 30% of adolescents and adults with 22q11.2DS, and psychotic disorders are seen in about 30% of adults (Schneider et al. 2014) (when ascertainment is not taken into account).

In the general population, psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, are effectively treated with both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies. For anxiety in particular, the latter can include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). Recommendations for these non-pharmacological treatments are documented in the guidelines by the American Psychiatric Association (APA, United States of America) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, United Kingdom).

Clinicians may wonder if standard treatment strategies are feasible and effective in 22q11.2DS, and if adaptations to treatment guidelines are required. For example, individuals with 22q11.2DS may need more time to establish a trusting relationship with clinicians, may need more time to process information, or may have difficulties understanding abstract information, due to intellectual disabilities and deficits in socialization (Fung et al. 2015). To begin to address the feasibility and efficacy of non-pharmacological therapies in 22q11.2DS, we used a systematic search strategy to identify literature on non-pharmacological interventions of psychiatric disorders in individuals with 22q11.2DS.

METHODS

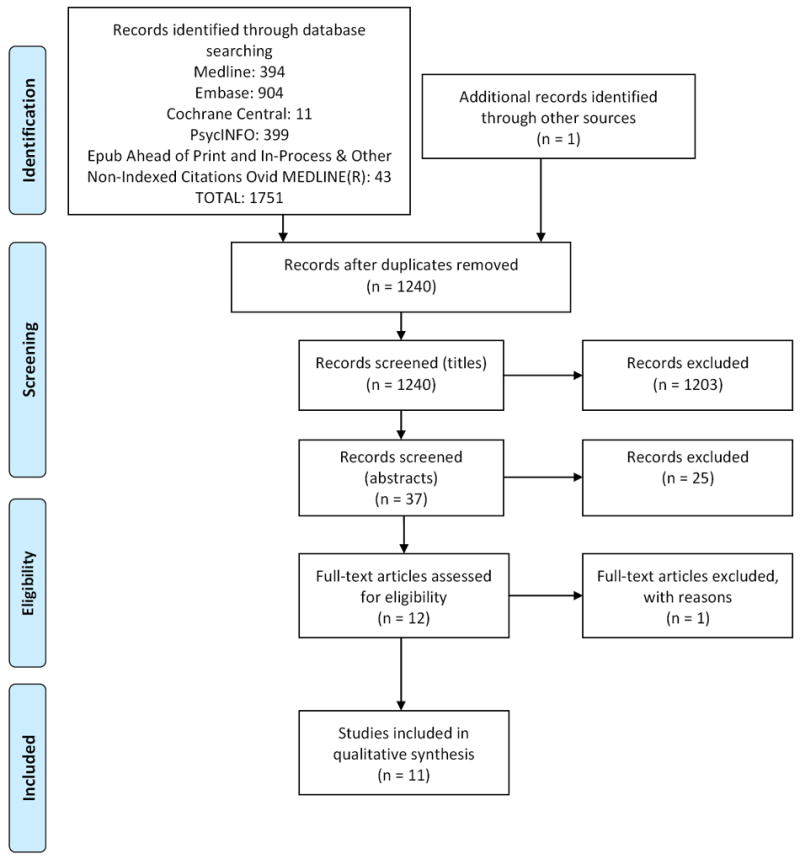

We attempted to identify all literature reporting on non-pharmacological treatment of psychiatric disorders in individuals with 22q11.2DS. A flow diagram, adapted from PRISMA 2009, depicting the literature search strategy is shown in Figure 1. We searched publications using the standard search engines for medicine (Medline, Embase, Cochrane central), behavioral sciences and education (PsychINFO), citation indices and research in progress (Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations Ovid MEDLINE®). We did not put any language or date restrictions on the search which was completed in the second week of July 2016. We searched for human studies with individuals of all ages, gender and race/ ethnicity. We searched all kinds of publications in journal articles, including research in progress, conference proceedings/ abstracts, dissertations and books. Search terms describing the population of individuals with 22q11.2DS included ‘22q11.2’, ‘velocardiofacial syndrome’, ‘DiGeorge syndrome’ and related terms. Based on a small preliminary search we expected a paucity of relevant literature and we broadened our search terms to all psychiatric disorders and all kinds of non-pharmacological interventions related to psychiatric disorders. The search terms used are presented in the online Supplemental material. We subsequently came across a relevant study published subsequent to this search and have added this publication to the review (Demily and Franck 2016).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram, descipting the systematic review search (Adapted from PRISMA 2009 flow Diagram)

All identified titles were imported in Reference Manager 12 (Thomson Reuters) and screened for duplication: first by the program itself, then manually by one of the investigators (PB). Titles, and subsequently abstracts, were screened for eligibility by two investigators (PB, EB). Potentially relevant articles were read and the references screened by one investigator (PB). All publications that discussed non-pharmacological interventions that may reduce the risk of developing and/or improve outcome in psychiatric disorders in individuals with 22q11.2DS were included. No publications were excluded.

RESULTS

The initial search identified 1240 titles, of which 11 publications (10 in English, 1 in German met inclusion criteria. A summary of the publications included in the review, two that refer to the same study, is provided in Table I.

Table I.

Summary of the publications included in the review.

| Literature Reviews (n = 5) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Study reference | Publication type | Design | Methods | Author’s conclusions | |

|

| |||||

| Bassett et al, 2011 | Article | Guideline | Systematic literature review and international 22q11.2DS consensus meetings | Standard management of psychiatric disorders is recommended | |

| Briegel et al, 2004 | Article† | Literature review | Literature review of 22q11.2DS | Standard treatment of psychiatric disorders is recommended | |

| Demily & Franck, 2016 | Article | Literature review | Literature review on idiopathic schizophrenia and 22q11.2DS | It is legitimate to propose CBT in 22q11.2DS | |

| Fung et al, 2010 | Article | Guideline | Systematic literature review and international 22q11.2DS consensus meetings | Standard management of psychiatric disorders is recommended | |

| Gothelf et al, 2013 | Book chapter | Literature review | Literature review ofn 22q11.2DS | Standard management of psychiatric disorders is recommended | |

|

| |||||

| Original research (n = 5) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Study reference | Publication type | Population | Intervention, incentive | Outcome measures | Author’s conclusions |

|

| |||||

| Eliez et al, 2011 | Abstract* (oral) | Intervention group: 28 22q11.2DS, ASD or DD (aged 8-16y), Control group: none | 12-weeks VisAVis; a Computerized software program, Incentive: NR | T-0, T+0 and T+12, Assessments: ‘Cognitive-behavioral evaluations’ (not specified) | VisAVis is a reliable tool for working on socio-emotional impairments in hard-to- treat pediatric populations |

| Eliez and Glaser, 2015 | Abstract* (oral) | Intervention group: 16 22q11.2DS (aged 7-16y) and 19 ASD (aged 7 16 y), Control group: 14 DD (aged 7-16y) | 12-weeks VisAVis Incentive: NR | T-0, T+0 and T12, Assessments: ‘Cognitive-behavioral evaluations’, including Children’s Memory Scale, and Raven Matrices | VisAVis is a useful tool for working on socio-emotional impairments in ASD and 22q11.2DS during middle childhood |

| Harrell et al, 2013 | Article | Intervention group: 13 22q11.2DS (aged 12-17y), Control group: 10 22q11.2DS (aged 12-17y) | 12-weeks, 4 × 40-minute sessions per week, BrainWorks™; an online computerized software program, Incentive: virtual (points) and actual (10 dollars per week), encouraging messages | T-0, T+0 and T+12, Assessments: 7 psychological tests assessing different domains | BrainWorks™ is feasible in children with 22q11.2DS, with high rates of adherence and satisfaction. Preliminary analyses indicate that gains in cognition occur with the intervention |

| Mariano et al, 2015 | Article | Intervention group: 21 22q11.2DS (aged 12-17y), Control group: intervention group served as their own controls | 8-months, 3 × 45-minute sessions per week, Challenging Our Minds; a video conference-based program Incentive: 10 dollar per session | T-32, T-0 and T+0, Assessments: WASI-II, BASC-2 PRS | A computerized CR program may be useful for youth with 22q11.2DS. It appears effective in enhancing cognitive skills during the developmental period of adolescence |

| Shashi et al, 2015 | Article | Intervention group: 13 22q11.2DS (aged 12-17y), Control group: 9 22q11.2DS (aged 12-17y) | 26-weeks, 1 × 60-minute session per week, small-group-based SCT program Incentive: 10 dollar per session attended, reimbursement for mileage | T-0 and T+0, Assessments: 7 psychological tests assessing different domains | SCT in a small-group format for adolescents with 22q11.2DS is feasible and results in gains in social cognition |

|

| |||||

| Other (n = 1) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Study reference | Publication type | Population | Intervention, incentive | Outcome measures | Author’s conclusions |

|

| |||||

| Fjermestad et al, 2015 | Article | Intervention group: 12 22q11.2DS (aged 12-17y), Control group: none | 7 × 45-minute group sessions, during 5 day residential stay, Incentive: NR | NR | Adaptations for interventions in 22q11.2DS are recommended |

22q11.2DS: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome; NR: not reported; CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; ASD: autism spectrum disorder; DD: developmental delay; T-#: number of weeks pre-intervention; T+#: number of weeks post-intervention; WASI-II: Weschler Abbreviated Test of Intelligence—Second Edition; BASC-2 PRS: The Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition Parent Rating Scale; CR: cognitive remediation; SCT: social cognitive training

In German;

These two abstracts refer to the same study and overall sample.

Literature reviews

Five of the 11 identified publications were literature reviews. Four of these referred to standard non-pharmacological interventions of psychiatric disorders in individuals with 22q11.2DS (Briegel and Cohen 2004; Bassett et al. 2011; Fung et al. 2015; Gothelf et al. 2013). The importance of adequate treatment of co-existing somatic conditions was highlighted in the practical guidelines for managing individuals with 22q11.2DS (Bassett et al. 2011; Fung et al. 2015a). The fifth publication reviewed literature on effective interventions in idiopathic schizophrenia and described similarities in the expression of schizophrenia and 22q11.2DS, such as impairments in executive functioning, memory, attention, and social cognition (Demily & Franck 2016). The authors proposed the use of CBT and discussed that adaptations may be needed in individuals with 22q11.2DS, though, as for the other reviews, in the absence of original data.

Original research

Of the 11 identified publications, 5 reported original research. As the two published abstracts refer to the same study population (Eliez et al. 2011; Eliez and Glaser 2015), we focused on the later abstract. Three of these four studies described computerized intervention programs (Eliez and Glaser 2015; Harrell et al. 2013; Mariano et al. 2015) and one described a small-group-based program (Shashi et al. 2015). All four of these original studies aimed at improving neuropsychological deficits that are associated with, and relevant to, the occurrence of psychiatric disorders.

Two of the original studies reported on the feasibility and effects of cognitive remediation (CR), based on the fact that deficits in cognitive functions have been found in individuals with psychotic disorders, and in individuals with 22q11.2DS with and without psychotic illness (Harrell et al., 2015; Mariano et al., 2015). Mariano et al offered an 8-month CR program (‘Challenging Our Minds’, Bracy et al. 1999) involving 45 minute or longer sessions provided 3 times per week via video conferencing. The program was completed by 22 adolescents with 22q11.2DS who served as their own controls. One participant was excluded from statistical analyses because internet connectivity problems invalidated the data obtained. The authors reported post-treatment improvements in working memory, shifting attention and cognitive flexibility with small to medium effect sizes. Harrell et al developed a 12-week computerized cognitive CR intervention, BrainWorks™, comprising four sessions per week and approximately 32 hours for the total program. Nine (69%) of 13 participating adolescents with 22q11.2DS completed the intervention; two did not complete the study due to inconsistent or unreliable internet access and two due to lack of motivation on the part of parents or participants. The authors reported improvements in simple processing speed and on a cognitive composite score in the treatment group when compared with a group of 10 age-matched adolescents with 22q11.2DS who did not receive the intervention. The authors of both of these CR studies concluded that CR is a feasible and effective intervention for individuals with a 22q11.2 deletion.

The study by Eliez et al (Eliez & Glaser 2015) reported on the use of a computerized software program they developed, VisAVis, that aims at improving working memory, emotion recognition, and face processing in children and adolescents with intellectual disability. A VisAVis computerized program consists of 12 weeks of 20-25 minute sessions 4 times per week for the individual patient, supervised by an adult (Glaser et al., 2012). The authors offered this program to 16 children and adolescents with 22q11.2DS, 19 with an autism spectrum disorder, and 14 with developmental delay who served as the comparison (control) group. Improvements in attention and concentration, nonverbal reasoning, and recognition of facial emotional expressions were reported for the 22q11.2DS-group (and for the autism spectrum disorder group), supporting the potential utility of the VisAVis program as a tool for improving socio-emotional-cognitive impairments.

In the only original study of a non-computerized intervention, Shashi et al aimed at improving social cognition and social skills in adolescents with 22q11.2DS, as deficits in these domains had been previously associated with an increased risk for developing serious psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia (Shashi et al., 2015). They adjusted a 26-week, small-group-based program involving cognitive enhancement therapy (CET, Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006), for a group of 17 adolescents with 22q11.2DS. Two sessions aimed at getting to know each other and providing psychoeducation about 22q11.2DS. Subsequent sessions included, but were not limited to, perspective thinking, awareness, recognition and mediation of emotions, social skills, flexible thinking, and identifying maladaptive thoughts and replacing them with more adaptive thoughts. One adolescent dropped out after two sessions (reason for drop out not reported) and three were excluded from analyses because of missing post-intervention assessments. The authors reported that the program was feasible, with high rates of compliance and satisfaction on the part of the participants and their families. Their preliminary analyses indicated that the small-group social cognitive training intervention used was feasible and resulted in significant improvements in an overall social cognitive composite index

Other

One of the 11 publications included in our review did not fit into either a review or original research category. While presented as a research paper, no outcome measures, control group, or study results were reported. The hypothesis presented was that established CBT protocols may be challenging to provide to individuals with 22q11.2DS due to their cognitive and social difficulties, and will therefore need adaptations (Fjermestad et al. 2015). The authors offered seven 45-minute sessions to 12 adolescents with 22q11.2DS, during a five-day residential stay, comprising three sessions aimed at getting to know each other and providing psychoeducation about 22q11.2DS, and four sessions with elements of CBT, i.e.; emotional awareness, relaxation, cognitive restructuring and problem solving. Suggestions for adaptations to accepted CBT protocols provided by the authors, apparently based on clinical experience but not substantiated by scientific evidence, included taking frequent breaks, providing enhanced repetition of concepts, and limiting use of writing exercises. The specific motivation for the adaptations of existing CBT protocols, the treatment goals, and treatment response were not specified.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified five literature reviews, five publications (two of which referred to the same study) reporting original data, and one publication that did not fall into either category. Four of the five literature reviews recommended standard non-pharmacological interventions. One of the reviews and a publication not fitting either category, though not substantiated by scientific evidence, suggested adaptations to standard interventions may be helpful. The four original studies reported on findings from research using promising computer-based and group interventions in individuals with 22q11.2DS. Strikingly, however, this review revealed that no research studying the efficacy and/or feasibility of standard or adjusted non-pharmacological interventions targeting common psychiatric disorders in individuals with 22q11.2DS has been published to date.

The results of this review make it perhaps understandable why standard non-pharmacological management has been recommended for 22q11.2DS (Briegel and Cohen 2004), including in the current international practical guidelines for 22q11.2DS (Bassett et al. 2011;Fung et al. 2015;Gothelf et al. 2013). However, there may be a disconnect between these guidelines and common clinical practice, given the reported under treatment of psychiatric disorders in this patient population (Tang et al. 2013; Young et al. 2011). 22q11.2DS-specific adjustments to standard treatment strategies may be necessary, as proposed in two of the papers included in this study (Fjermestad et al. 2015; Demily and Franck 2016), and as is the practice for individuals with an intellectual disability (Lindsay et al. 2015; Idusohan-Moizer et al. 2015).

Four preliminary studies have however investigated interventions targeting deficits in neuropsychological domains of functioning that are associated with expression of psychosis, such as cognitive abilities and socio-emotional functioning (Eliez & Glaser 2015, Harrell et al. 2013; Mariano et al. 2015; Shashi et al. 2015). Three reported using some sort of control method, including approaches to reduce bias (Harrell et al. 2013; Mariano et al. 2015; Shashi et al. 2015). Harrell et al. non-randomly assigned children to a control group and reported no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in age, gender, or race (Harrell et al. 2013). Shashi et al. assigned participants who did not live in the vicinity to a control group and matched the intervention and control groups for age, gender and ethnicity (Shashi et al. 2015). Mariano et al. used the intervention group as their own controls (Mariano et al. 2015). All three of these studies also reported on the feasibility of their intervention and reported substantial adherence rates (Harrell et al. 2013; Mariano et al. 2015; Shashi et al. 2015). It should however be noted that compensation of 10 dollars per week for participated sessions was provided, something uncommon in clinical practice, and this may have had an impact on adherence rates (Harrell et al. 2013; Mariano et al. 2015; Shashi et al. 2015). Promising improvements were reported immediately and/or at 12 weeks post-intervention in several domains of neuropsychological functioning, including working memory, attention, and social cognition, in all five of the preliminary studies, despite relatively small sample sizes.

In summary, there is limited literature on non-pharmacological treatment of psychiatric disorders in individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The results of this systematic review indicate that there are as yet insufficient data available to warrant adjustments to current clinical guidelines for 22q11.2DS. To inform clinical care, future research using adequately powered samples, and standard randomized controlled clinical trials methodology, to study the feasibility and efficacy of non-pharmacological treatment of psychiatric disorders in individuals with 22q11.2DS is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Melanie Anderson, information specialist, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada for her assistance in the systematic review.

Financial support and sponsorship

Supported by funding from; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP nos. 97800 and 111238; ASB); the NIMH (5U01MH101723-02; ASB and EB); the University of Toronto McLaughlin Centre (ASB); and from the Dalglish Fellowship in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome awarded to EB. ASB holds the Dalglish Chair in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome at the Toronto General Hospital.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, United States of America. Practice Guidelines. http://www.psychiatryonline.org.

- Bassett AS, McDonald-Mcginn DM, Devriendt K, Digilio MC, Goldenberg P, Habel A, Marino B, Oskarsdottir S, Philip N, Sullivan K, Swillen A, Vorstman J. Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;159(2):332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracy OD, Oakes AL, Cooper RS, Watkins D, Watkins M, Brown DE, Jewell C. The effects of cognitive rehabilitation therapy techniques for enhancing the cognitive/intellectual functioning of seventh- and eighth-grade children. Cognitive Technology. 1999;4(1):19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Briegel W, Cohen M. Chromosome 22q11 deletion syndrome and its relevance for child and adolescent psychiatry. An overview of etiology, physical symptoms, aspects of child development and psychiatric disorders. Zeitschrift fur Kinder-und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2004;32(2):107–115. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917.32.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demily C, Franck N. Cognitive behavioral therapy in 22q11.2 microdeletion with psychotic symptoms: What do we learn from schizophrenia? European Journal of Medical Genetics. 2016;59(11):596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliez S, Dukes D, Martinez S, Pasca C, Lothe A, Glaser B. Socio-emotional remediation for persons with autism spectrum disorder or other developmental disabilities. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;20:S86. [Google Scholar]

- Eliez S, Glaser B. Evidence-based program for improving socio-emotional skills and executive function in children and adolescents with autism and developmental delay. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;1:S46. [Google Scholar]

- Fjermestad KW, Vatne TM, Gjone H. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities. 2015;9(1):30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fung WL, Butcher NJ, Costain G, Andrade DM, Boot E, Chow EW, Chung B, Cytrynbaum C, Faghfoury H, Fishman L, Garcia-Minaur S, George S, Lang AE, Repetto G, Shugar A, Silversides C, Swillen A, van AT, McDonald-McGinn DM, Bassett AS. Practical guidelines for managing adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Genetics in Medicine. 2015b;17(8):599–609. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung WL, McEvilly R, Fong J, Silversides C, Chow E, Bassett A. Elevated prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):998. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf D, Burg M, Zalevsky M. Educating children with velo-cardio-facial syndrome, also known as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and DiGeorge syndrome. second edition. San Diego: Plural Publishing; 2013. Psychiatric disorders and treatment in velo-cardio-facial syndrome; pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Lothe A, Chabloz M, Dukes D, Pasca C, Redoute J, Eliez S. Candidate Socioemotional Remediation Program for Individuals with Intellectual Disability. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental disabilities. 2012;117(5):368–383. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.5.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell W, Eack S, Hooper SR, Keshavan MS, Bonner MS, Schoch K, Shashi V. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy data from a computerized cognitive intervention in children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34(9):2606–2613. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP. Cognitive enhancement therapy: the training manual. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Idusohan-Moizer H, Sawicka A, Dendle J, Albany M. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for adults with intellectual disabilities: an evaluation of the effectiveness of mindfulness in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2015;59:93–104. doi: 10.1111/jir.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay WR, Tinsley S, Beail N, Hastings RP, Jahoda A, Taylor JL, Hatton C. A preliminary controlled trial of a trans-diagnostic programme for cognitive behaviour therapy with adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2015;59:360–369. doi: 10.1111/jir.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariano MA, Tang K, Kurtz M, Kates WR. Cognitive remediation for adolescents with 22q11 deletion syndrome (22q11DS): a preliminary study examining effectiveness, feasibility, and fidelity of a hybrid strategy, remote and computer-based intervention. Schizophrenia Research. 2015;166(1-3):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE, Marino B, Philip N, Swillen A, Vorstman JA, Zackai EH, Emanuel BS, Vermeesch JR, Morrow BE, Scambler PJ, Bassett AS. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2015;1:15071. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, United Kingdom. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance.

- Schneider M, Debbane M, Bassett AS, Chow EW, Fung WL, van den Bree M, Owen M, Murphy KC, Niarchou M, Kates WR, Antshel KM, Fremont W, McDonald-McGinn DM, Gur RE, Zackai EH, Vorstman J, Duijff SN, Klaassen PW, Swillen A, Gothelf D, Green T, Weizman A, van AT, Evers L, Boot E, Shashi V, Hooper SR, Bearden CE, Jalbrzikowski M, Armando M, Vicari S, Murphy DG, Ousley O, Campbell LE, Simon TJ, Eliez S. Psychiatric disorders from childhood to adulthood in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: results from the International Consortium on Brain and Behavior in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):627–639. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashi V, Harrell W, Eack S, Sanders C, McConkie-Rosell A, Keshavan M, Bonner M, Schoch K, Hooper S. Social cognitive training in adolescents with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Feasibility and preliminary effects of the intervention. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2015;59(10):902–913. doi: 10.1111/jir.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SX, Yi JJ, Calkins ME, Whinna DA, Kohler CG, Souders MC, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Emanuel BS, Gur RC, Gur RE. Psychiatric disorders in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome are prevalent but undertreated. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44(6):1267–1277. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AS, Shashi V, Schoch K, Kwapil T, Hooper SR. Discordance in Diagnoses and Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents with 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;4(2):119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.