Abstract

Essentials.

Recent randomized trials suggested fewer bleeding events in fragile patients with VTE receiving DOACs.

The frequency, clinical characteristics and outcome of these patients have not been reported in real life.

Fragile patients with VTE had a higher risk for major bleeding or death and a lower risk for recurrences than non‐fragile.

Background

Subgroup analyses from randomized trials suggested favorable results for the direct oral anticoagulants in fragile patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE). The frequency and natural history of fragile patients with VTE have not been studied yet.

Objectives

To compare the clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes during the first 3 months of anticoagulation in fragile vs non‐fragile patients with VTE.

Methods

Retrospective study using consecutive patients enrolled in the RIETE (Registro Informatizado Enfermedad TromboEmbolica) registry. Fragile patients were defined as those having age ≥75 years, creatinine clearance (CrCl) levels ≤50 mL/min, and/or body weight ≤50 kg.

Results

From January 2013 to October 2016, 15 079 patients were recruited. Of these, 6260 (42%) were fragile: 37% were aged ≥75 years, 20% had CrCl levels ≤50 mL/min, and 3.6% weighed ≤50 kg. During the first 3 months of anticoagulant therapy, fragile patients had a lower risk of VTE recurrences (0.78% vs 1.4%; adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 0.52; 95% confidence intervals [CI]: 0.37‐0.74) and a higher risk of major bleeding (2.6% vs 1.4%; adjusted OR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.10‐1.80), gastrointestinal bleeding (0.86% vs 0.35%; adjusted OR: 1.84; 95% CI: 1.16‐2.92), haematoma (0.51% vs 0.07%; adjusted OR: 5.05; 95% CI: 2.05‐12.4), all‐cause death (9.2% vs 3.5%; adjusted OR: 2.02; 95% CI: 1.75‐2.33), or fatal PE (0.85% vs 0.35%; adjusted OR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.10‐2.85) than the non‐fragile.

Conclusions

In real life, 42% of VTE patients were fragile. During anticoagulation, they had fewer VTE recurrences and more major bleeding events than the non‐fragile.

Keywords: anticoagulants, hemorrhage, mortality, recurrences, venous thromboembolism

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, a number of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have been developed for the treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Their use has been associated with a lower rate of major bleeding compared with standard therapy.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Hence, apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and edoxaban have been approved for the treatment of patients with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).6 Subgroup analyses from these randomized clinical trials have delivered further promising results, particularly for the so‐called fragile patients, defined as those having creatinine clearance (CrCl) levels ≤50 mL/min, age ≥75 years, or body weight ≤50 kg.3, 4, 5, 7 Hence, there are reasons to suggest that fragile patients with VTE could be considered ideal candidates for long‐term therapy with DOACs.4, 5, 7, 8 However, the proportion of fragile patients in real life, and their outcome during the course of anticoagulant therapy have not been thoroughly studied yet.

RIETE (Registro Informatizado Enfermedad TromboEmbólica) is a multicenter, ongoing, international (Spain, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, Ecuador, France, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Republic of Macedonia, Switzerland, and the United States enroll patients) registry of consecutive patients with symptomatic, objectively confirmed, acute VTE (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02832245).9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Since its inception in 2001, the aim of RIETE is to record data including the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcomes in patients diagnosed with VTE. Using the RIETE database, the current study compared the clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes during the first 3 months of anticoagulation in fragile vs non‐fragile patients with acute VTE.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Inclusion criteria

Consecutive patients presenting with symptomatic, acute DVT or PE confirmed by objective tests (compression ultrasonography or contrast venography for DVT; helical CT‐scan, ventilation‐perfusion lung scintigraphy or angiography for PE) were enrolled in RIETE. Patients were excluded if they were currently participating in a therapeutic clinical trial with a blinded therapy. All patients (or their legal power of attorney) provided written or oral consent for participation in the registry, in accordance with local ethics committee requirements.

Physicians participating in the RIETE registry made all efforts to enroll consecutive patients. Data were recorded onto a computer‐based case‐report form at each participating hospital and submitted to a centralized coordinating center through a secure website. To ensure the validity of the information entered into the database, one of the specially trained monitors visited each participating hospital and compared information in 25‐50 randomly chosen patient records with the information entered into the RIETE database. For data quality assessment, monitors assessed 4100 random records from all participating hospitals, which included 1 230 000 measurements. These data showed a 95% overall agreement between the registered information and patient records. RIETE also used electronic data monitoring to detect inconsistencies or errors and attempted to resolve discrepancies by contacting the local coordinators.

2.2. Study design

We conducted a cohort study that used consecutive patients enrolled in the RIETE registry. For this study, only patients recruited from January 2013 (the year when the first DOAC was approved for use in patients with VTE) were considered. Our aim was to compare the clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes in fragile vs non‐fragile patients. The major outcome was the rate of VTE recurrences or major bleeding occurring during the first 3 months of anticoagulant therapy.

2.3. Definitions

Fragile patients were defined as those having CrCl levels ≤50 mL/min, age ≥75 years, or body weight ≤50 kg.3 Immobilized patients were defined as non‐surgical patients who had been immobilized (ie, total bed rest with bathroom privileges) for ≥4 days in the 2‐month period prior to VTE.12 Surgical patients were defined as those who underwent a surgical intervention in the 2 months prior to VTE.11 Active cancer was defined as newly diagnosed cancer, metastatic cancer, or cancer that was being treated (ie, surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, support therapy).10 Recent bleeding was defined as any major bleeding episode <30 days prior to VTE.14 Bleeding events were classified as “major” if they were overt and required a transfusion of two units or more of blood, or were retroperitoneal, spinal, or intracranial, or when they were fatal. Fatal bleeding was defined as any death occurring within 10 days of a major bleeding episode, in the absence of an alternative cause of death.14 Fatal PE, in the absence of autopsy, was defined as any death appearing within 10 days after symptomatic PE diagnosis, in the absence of any alternative cause of death.12 Initial therapy was defined as any therapy administered during the first week in case of low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH), unfractionated heparin, fondaparinux, or apixaban, and during the first 3 weeks in case of rivaroxaban. Long‐term therapy was defined as any therapy administered after the end of initial therapy.

2.4. Treatment and follow‐up

Patients were managed according to each participating hospital's clinical practice, and there were no standardized or recommended duration of therapy or follow‐up. All patients had to be followed‐up for at least 3 months in the outpatient clinic or physician's office. During each visit, any signs or symptoms suggesting VTE recurrences or bleeding complications were noted. Each episode of clinically suspected recurrent VTE was investigated by repeat compression ultrasonography, lung scanning, helical‐CT scan, or pulmonary angiography, as appropriate. Most outcomes were classified as reported by the clinical centers. However, if staff at the coordinating center were uncertain how to classify a reported outcome, that event was reviewed by a central adjudicating committee (less than 10% of events).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics, risk factors, and initial VTE presentation were analyzed using descriptive statistics for continuous variables and frequency counts and percentages for categorical variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi‐square test (two‐sided) and Fisher′s exact test (two‐sided). Continuous variables were compared using Student's t test. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), as well as P‐values (Mann‐Whitney test or t test for continuous variables and Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel tests for categorical variables) were presented for each variable analyzed. All outcomes were analyzed in the overall follow‐up period (0‐90 days). Univariate analysis was conducted yielding odds ratios with 95% CI, as well as P‐values (Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel tests) for each outcome. Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis was conducted to investigate the risk of outcomes in both subgroups for the overall period (0‐90 days).

Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare the rates of VTE recurrences and major bleeding in the two subgroups during the 90‐day follow‐up period. Covariates included in the adjusted model were those for which a statistically significant difference (a threshold P‐value of .1 was set to assess significance of differences) was found between the two subgroups, and a backward selection was used for the covariate selection in the multivariate model. For both Kaplan‐Meier survival analyses and Cox regression analyses, if a patient did not have a study outcome of interest before the cut‐off time of 90 days or if he died, then the time‐to‐event was censored. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS for Windows Release 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

3. RESULTS

From January 2013 to October 2016, 15 079 patients with acute VTE were recruited in RIETE. Of these, 6260 (42%) were fragile: 5514 (37%) were aged ≥75 years, 537 (3.6%) weighed ≤50 kg, and 3059 (20%) had CrCl levels ≤50 mL/min. Fragile patients were less likely to be men (38% vs 57%) and more likely to have had recent immobility, cancer, chronic heart or lung disease, recent major bleeding, anemia, or abnormal platelet count than the non‐fragile, but were less likely to have had recent surgery or estrogen use (Table 1). Fragile patients more likely presented initially with PE (with or without concomitant DVT) as compared with DVT alone (60% vs 53%).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in 15 079 fragile and non‐fragile patients with acute venous thromboembolism

| Non‐fragile | Fragile | Age ≥ 75 y | Weight ≤ 50 kg | CrCl ≤ 50 mL/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | 8819 | 6260 | 5514 | 537 | 3059 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Age (y ± SD) | 55 ± 14 | 80 ± 10‡ | 82 ± 5.0 | 71 ± 2.0 | 81 ± 10 |

| Gender (male) | 5058 (57%) | 2407 (38%)‡ | 2104 (38%) | 73 (14%) | 1030 (34%) |

| Body weight (kg ± SD) | 81 ± 17 | 71 ± 14‡ | 72 ± 14 | 47 ± 4. | 67 ± 13 |

| Risk factors for VTE | |||||

| Immobilization ≥4 d | 1342 (15%) | 1648 (26%)‡ | 1488 (27%) | 165 (31%) | 894 (29%) |

| Surgery | 1097 (12%) | 502 (8.0%)‡ | 406 (7.4%) | 48 (8.9%) | 228 (7.5%) |

| Cancer | 1894 (21%) | 1495 (24%)‡ | 1235 (22%) | 164 (31%) | 723 (24%) |

| Estrogen use | 813 (9.2%) | 222 (3.5%)‡ | 160 (2.9%) | 53 (9.9%) | 92 (3.0%) |

| Pregnancy/puerperium | 172 (2.0%) | 7 (0.11%)‡ | 0 | 4 (0.74%) | 3 (0.10%) |

| None of the above | 4353 (49%) | 3004 (48%) | 2731 (50%) | 175 (33%) | 1425 (47%) |

| Prior VTE | 1352 (15%) | 906 (14%) | 821 (15%) | 58 (11%) | 419 (14%) |

| Underlying diseases | |||||

| Chronic heart failure | 254 (2.9%) | 775 (12%)‡ | 720 (13%) | 56 (10%) | 469 (15%) |

| Chronic lung disease | 801 (9.1%) | 1015 (16%)‡ | 904 (16%) | 62 (12%) | 495 (16%) |

| Recent major bleeding | 170 (1.9%) | 168 (2.7%)† | 132 (2.4%) | 15 (2.8%) | 82 (2.7%) |

| Blood tests | |||||

| Anemia | 2492 (28%) | 2514 (40%)‡ | 2116 (38%) | 275 (51%) | 1430 (47%) |

| Platelet count <150 000/μL | 1083 (12%) | 1036 (17%)‡ | 884 (16%) | 70 (13%) | 537 (18%) |

| Platelet count >450 000/μL | 249 (2.8%) | 185 (3.0%) | 151 (2.7%) | 35 (6.5%) | 95 (3.1%) |

| CrCl levels (mL/min ± SD) | 108 ± 50 | 54 ± 24‡ | 55 ± 23 | 54 ± 38 | 36 ± 10 |

| Initial VTE presentation | |||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 4698 (53%) | 3751 (60%)‡ | 3364 (61%) | 280 (52%) | 1853 (61%) |

CrCl, creatinine clearance; SD, standard deviation; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Comparisons between fragile and non‐fragile patients: *P < .05; † P < .01; ‡ P < .001. Anemia was considered in men with haemoglobin levels <13 g/dL or women with levels <12 g/dL.

Fragile patients more often received initial therapy with LMWH (88% vs 83%) or UFH (5.0% vs 4.3%), but less often fondaparinux (2.2% vs 3.6%) or rivaroxaban (2.4% vs 6.1%), as shown in Table 2. For long‐term therapy, fragile patients more often received VKA (54% vs 50%) and less often rivaroxaban (8.4% vs 17%) than the non‐fragile. The proportion of patients receiving apixaban or dabigatran was small and similar in both subgroups. Moreover, fragile patients on long‐term LMWH therapy received lower mean daily doses per body weight than the non‐fragile. Mean duration of therapy was slightly shorter in fragile than in non‐fragile patients (207 ± 190 vs 214 ± 179 days, respectively; P = .026).

Table 2.

Treatment strategies in fragile and non‐fragile patients with acute venous thromboembolism

| Non‐fragile | Fragile | Age ≥75 y | Weight ≤ 50 kg | CrCl ≤ 50 mL/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | 8819 | 6260 | 5514 | 537 | 3059 |

| Initial therapy | |||||

| LMWH | 7288 (83%) | 5493 (88%)‡ | 4879 (88%) | 472 (88%) | 2660 (87%) |

| LMWH doses (IU/kg/d) | 173 ± 43 | 172 ± 45 | 171 ± 44 | 187 ± 55 | 169 ± 47 |

| Unfractionated heparin | 382 (4.3%) | 316 (5.0%)* | 244 (4.4%) | 26 (4.8%) | 215 (7.0%) |

| Fondaparinux | 317 (3.6%) | 136 (2.2%)‡ | 124 (2.2%) | 13 (2.4%) | 56 (1.8%) |

| Rivaroxaban | 534 (6.1%) | 151 (2.4%)‡ | 134 (2.4%) | 14 (2.6%) | 44 (1.4%) |

| Apixaban | 27 (0.31%) | 17 (0.27%) | 16 (0.29%) | 1 (0.19%) | 11 (0.36%) |

| Long‐term therapy | |||||

| LMWH | 2551 (29%) | 1879 (30%) | 1583 (29%) | 242 (45%) | 965 (32%) |

| LMWH doses (IU/kg/d) | 153 ± 44 | 146 ± 45‡ | 145 ± 43 | 159 ± 48 | 144 ± 46 |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 4415 (50%) | 3401 (54%)‡ | 3069 (56%) | 192 (36%) | 1643 (54%) |

| Rivaroxaban | 1452 (17%) | 505 (8.4%)‡ | 456 (8.6%) | 42 (8.4%) | 172 (6.0%) |

| Apixaban | 130 (1.5%) | 93 (1.6%) | 87 (1.6%) | 7 (1.4%) | 47 (1.6%) |

| Dabigatran | 28 (0.32%) | 21 (0.35%) | 21 (0.40%) | 2 (0.40%) | 6 (0.21%) |

CrCl, creatinine clearance; IU, international units; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin.

Comparisons between fragile and non‐fragile patients: *P < .05; † P < .01; ‡ P < .001.

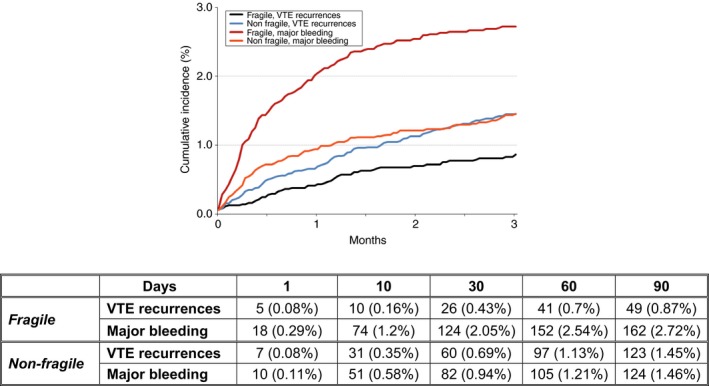

During the first 3 months of anticoagulant therapy, fragile patients had a lower risk of VTE recurrences (0.78% vs 1.4%; OR: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.40‐0.78) and a higher risk of major bleeding (2.6% vs 1.4%; OR: 1.86; 95% CI: 1.47‐2.36) than the non‐fragile (Table 3). The risk of DVT recurrences was particularly lower (0.37% vs 0.90%; OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.26‐0.65) while the risk of PE recurrences was non‐significantly lower (0.43% vs 0.53%; OR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.50‐1.30). Fragile patients also had a higher risk of all‐cause death (9.2% vs 3.5%; OR: 2.82; 95% CI: 2.44‐3.25), fatal PE (0.85% vs 0.32%; OR: 2.68; 95% CI: 1.69‐4.24), and fatal bleeding (0.35% vs 0.19%; OR: 1.83; 95% CI: 0.97‐3.44) compared with non‐fragile. In fragile patients, the risk of VTE recurrences was one‐third the rate of major bleeding (49 vs 162 events, respectively) from the beginning of therapy (Figure 1). In non‐fragile patients, both risks were similar (123 vs 124 events, respectively).

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes during the first 3 months of anticoagulant therapy in fragile vs non‐fragile patients with VTE

| Fragile | Non‐fragile | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | 6260 | 8819 | ||

| Events | ||||

| Recurrent VTE | 49 (0.78%) | 123 (1.4%) | 0.56 (0.40‐0.78) | 0.52 (0.37‐0.74) |

| Recurrent PE | 27 (0.43%) | 47 (0.53%) | 0.81 (0.50‐1.30) | — |

| Recurrent DVT | 23 (0.37%) | 79 (0.90%) | 0.41 (0.26‐0.65) | 0.41 (0.25‐0.67) |

| Major bleeding | 162 (2.6%) | 124 (1.4%) | 1.86 (1.47‐2.36) | 1.41 (1.10‐1.80) |

| Sites of major bleeding | ||||

| Gastrointestinal | 54 (0.86%) | 31 (0.35%) | 2.47 (1.58‐3.84) | 1.84 (1.16‐2.92) |

| Cerebral | 20 (0.32%) | 21 (0.24%) | 1.34 (0.73‐2.48) | — |

| Haematoma | 32 (0.51%) | 6 (0.07%) | 7.55 (3.15‐18.1) | 5.05 (2.05‐12.4) |

| Retroperitoneal | 16 (0.26%) | 11 (0.12%) | 2.05 (0.95‐4.42) | — |

| Death | 574 (9.2%) | 305 (3.5%) | 2.82 (2.44‐3.25) | 2.02 (1.75‐2.33) |

| Causes of death | ||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 53 (0.85%) | 28 (0.32%) | 2.68 (1.69‐4.24) | 1.77 (1.10‐2.85) |

| Initial PE | 49 (0.78%) | 23 (0.26%) | 3.02 (1.84‐4.96) | 1.91 (1.14‐3.20) |

| Recurrent PE | 4 (0.06%) | 5 (0.06%) | 1.13 (0.30‐4.20) | — |

| Bleeding | 22 (0.35%) | 17 (0.19%) | 1.83 (0.97‐3.44) | — |

| Cerebral | 8 (0.13%) | 6 (0.07%) | 1.88 (0.65‐5.42) | — |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (0.06%) | 3 (0.03%) | 1.88 (0.42‐8.40) | — |

| Retroperitoneal | 5 (0.08%) | 1 (0.01%) | 7.05 (0.82‐60.3) | — |

| Respiratory insufficiency | 44 (0.70%) | 24 (0.27%) | 2.59 (1.58‐4.27) | — |

| Sudden, unexpected | 16 (0.26%) | 12 (0.14%) | 1.88 (0.89‐3.98) | — |

CI, confidence intervals; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; OR, odds ratio; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Variables included in the multivariable analysis for VTE recurrence: fragile, active cancer, prior VTE, chronic heart failure, abnormal platelet count, and initial VTE presentation (DVT or PE).

Variables included in the multivariable analysis for major bleeding: fragile, gender, active cancer, chronic lung disease, recent major bleeding, anaemia, abnormal platelet count, and initial VTE presentation (DVT or PE).

Variables included in the multivariable analysis for death: fragile, gender, active cancer, recent surgery, recent immobilization, prior VTE, chronic lung disease, chronic heart failure, recent major bleeding, anaemia, abnormal platelet count, and initial VTE presentation (DVT or PE).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) recurrence and major bleeding during the first 3 months of anticoagulant therapy in fragile vs non‐fragile patients

When separately analyzing outcomes, the risk of major bleeding in patients weighing <50 kg was similar to the risk in non‐fragile, in patients aged ≥75 years it was slightly (but significantly) higher, and in those with CrCl levels <50 mL/min it was over 3‐fold higher than in non‐fragile (Table 4).

Table 4.

Rates of VTE recurrences and major bleeding, according to the presence of age ≥75 years, CrCl ≤50 mL/min and/or body weight ≤50 kg

| N | VTE recurrences | Major bleeding | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | OR (95% CI) | N (%) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Non‐fragile | 8819 | 123 (1.4%) | Ref. | 124 (1.4%) | Ref. |

| Age ≥75 years only | 2967 | 22 (0.7%) | 0.5 (0.3‐0.8) | 62 (2.1%) | 1.5 (1.1‐2.0) |

| CrCl ≤50 mL/min only | 521 | 6 (1.2%) | 0.8 (0.3‐1.8) | 23 (4.4%) | 3.2 (2.0‐5.0) |

| Body weight ≤50 kg only | 183 | 3 (1.6%) | 1.2 (0.3‐3.3) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.8 (0.1‐2.6) |

| Age ≥75 years and CrCl ≤50 mL/min | 2235 | 16 (0.7%) | 0.5 (0.3‐0.8) | 60 (2.7%) | 1.9 (1.4‐2.6) |

| Age ≥75 years and body weight ≤50 kg | 51 | 0 | — | 1 (2.0%) | 1.4 (0.1‐7.3) |

| CrCl ≤50 mL/min and weight ≤50 kg | 42 | 1 (2.4%) | 1.7 (0.1‐9.0) | 2 (4.8%) | 3.5 (0.6‐12.4) |

| All 3 conditions | 261 | 1 (0.4%) | 0.3 (0.01‐1.4) | 12 (4.6%) | 3.4 (1.8‐6.0) |

CI, confidence intervals; CrCl, creatinine clearance; OR, odds ratio; Ref., reference; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

4. DISCUSSION

The term “fragile” has been recently incorporated into the literature to include VTE patients who are elderly, renally impaired, or with low body weight.3 This term should not be confused with “frail,” which usually refers to elderly people with reduced physiologic reserve associated with increased susceptibility to disability.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Our findings, obtained from a large series of consecutive patients with VTE, reveal that in real life 42% of patients were fragile, and that during the first 3 months of anticoagulant therapy they had half the risk of VTE recurrences and a higher risk of major bleeding than the non‐fragile. Among fragile patients, the risk of VTE recurrences was much lower than the risk of major bleeding (49 vs 162 events). Among non‐fragile patients, the risk of VTE recurrences and major bleeding were the same (123 vs 124 events, respectively). Thus, there are reasons to suggest that when choosing an anticoagulant therapy for fragile patients with VTE, safety is an important issue.

Recent randomized trials on patients with VTE provided indirect evidence on a number of advantages in fragile patients receiving DOACs.5, 7, 20 In the EINSTEIN‐DVT and PE trials, the risk of major bleeding was much lower in fragile patients on rivaroxaban than in those on standard therapy (HR: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.13‐0.54).7 This difference was not seen in non‐fragile patients. In the HOKUSAI trial a higher efficacy (defined as symptomatic recurrent venous thromboembolism) was found using edoxaban than with warfarin in fragile patients (2.5% vs 4.8%; P = .04), without any safety concern (11.0% vs 13.7%; P = .87).5 Unexpectedly, however, in our cohort rivaroxaban was less likely to be prescribed in fragile than in non‐fragile patients, both initially (2.4% vs 6.1%, respectively) and for long‐term therapy (8.4% vs 17%).

Our data confirm that the use of anticoagulant therapy carries a higher risk to bleed than to recur in the elderly and in the renally impaired, as previously reported.14, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 During initial therapy with LMWH, fragile patients weighing ≤50 kg received slightly higher (non‐significantly) mean daily doses per body weight of LMWH compared with non‐fragile patients. This might explain, at least in part, the higher risk of major bleeding in fragile patients. Moreover, since fragile patients had more underlying diseases, they probably used more drugs than the non‐fragile patients. Thus, the increased risks of major bleeding during anticoagulation in fragile patients could be explained, at least in part, by these other drugs that might have potentiated the effect of the anticoagulant therapy. The similar risk for bleeding than for VTE recurrences in VTE patients weighing ≤50 kg has not been consistently reported.26, 27, 28 These findings suggest the potential benefit of tailored therapy for VTE according to clinical characteristics of the patients and warrant external validation.

The present study has a number of potential limitations. First, since RIETE is an observational registry (and not a randomized trial) our data are hypothesis‐generating. They might be a useful basis for future controlled clinical trials comparing different therapeutic strategies, but we should be extremely cautious in suggesting changes in treatment strategies just because of uncontrolled registry data. Second, patients were not treated with a standardized anticoagulant regimen; treatment varied with local practice, and is likely to have been influenced by a physician's assessment of a patient's risk of bleeding. Finally, patients in the RIETE database resided in several different countries. The variability of practices in different countries could potentially affect the study outcomes. Furthermore, a variety of practitioners entered data into the registry, which may lend itself to potential inaccuracies in the data being reported. The main strengths of our observation are the high number of included patients, the strict diagnostic criteria and the reporting of objectively established outcomes (major bleeding and recurrent VTE). Additionally, the population‐based sample we used describes the effects of anticoagulant therapy in “real‐world” clinical care, as opposed to in a protocol‐driven randomized trial, and enhances the generalizability of our findings.

In summary, in real life 42% of VTE patients were fragile, and these patients had fewer VTE recurrences and more major bleeding events during the course of anticoagulant therapy than the non‐fragile. Randomized trials are warranted to confirm whether the use of DOACs could be safer than standard anticoagulant therapy in fragile patients with VTE.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F. Moustafa contributed to the design, analysis, and interpretation of data, collected patients, and wrote the article. M. Giorgi‐Pierfranceschi contributed to the interpretation of data, collected patients, and approved the final version of the article. P. Di Micco contributed to the interpretation of data, collected patients, and approved the final version of the article. E. Bucherini contributed to the interpretation of data, collected patients, and approved the final version of the article. A. Lorenzo contributed to the interpretation of data, collected patients, and approved the final version of the article. A. Villalobos contributed to the interpretation of data, collected patients, and approved the final version of the article. JA. Nieto collected patients and approved the final version of the article. B. Valero collected patients and approved the final version of the article. AL. Samperiz collected patients and approved the final version of the article. M. Monreal contributed to the design, analysis, and interpretation of data, collected patients, wrote the article, and obtained funding.

RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE

Dr. Moustafa has served as an advisor or consultant for Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi; has served as a speaker for Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi‐Sankyo and Sanofi; and has received grants from Sanofi, Bayer HealthCare and LFB. Dr. Monreal has served as an advisor or consultant for Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and Sanofi; has served as a speaker or a member of a speaker's bureau for Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Leo Pharma, and Sanofi; and has received grants for clinical research from Sanofi and Bayer. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express our gratitude to Sanofi Spain for supporting this registry with an unrestricted educational grant. We also express our gratitude to Bayer Pharma AG for supporting this registry. Bayer Pharma AG's support was limited to the part of RIETE outside Spain, which accounts for 23.46% of the total patients included in the RIETE Registry. We also thank the RIETE Registry Coordinating Center, S & H Medical Science Service, for their quality control data, logistic, and administrative support, and Prof. Salvador Ortiz, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid and Statistical Advisor S& H Medical Science Service for the statistical analysis of the data presented in this paper.

APPENDIX 1.

1.1.

Coordinator of the RIETE Registry: Manuel Monreal.

RIETE Steering Committee Members: Hervé Decousus, Paolo Prandoni, and Benjamin Brenner.

RIETE National Coordinators: Raquel Barba (Spain), Pierpaolo Di Micco (Italy), Laurent Bertoletti (France), Inna Tzoran (Israel), Abilio Reis (Portugal), Marijan Bosevski (R. Macedonia), Henri Bounameaux (Switzerland), Radovan Malý (Czech Republic), Philip Wells (Canada), and Manolis Papadakis (Greece).

RIETE Registry Coordinating Center: S & H Medical Science Service.

Members of the RIETE Group: SPAIN – Adarraga MD, Agudo P, Aibar MA, Alfonso M, Arcelus JI, Ballaz A, Barba R, Barrón M, Barrón‐Andrés B, Bascuñana J, Blanco‐Molina A, Cañas I, Casado I, Chic N, del Pozo R, del Toro J, Díaz‐Pedroche MC, Díaz‐Peromingo JA, Falgá C, Fernández‐Aracil C, Fernández‐Capitán C, Fidalgo MA, Font C, Font L, Gallego P, García MA, García‐Bragado F, Gavín O, Gómez C, Gómez V, González J, Grau E, Grimón A, Guijarro R, Guirado L, Gutiérrez J, Hernández‐Comes G, Hernández‐Blasco L, Jara‐Palomares L, Jaras MJ, Jiménez D, Jiménez J, Joya MD, Llamas P, Lobo JL, López P, López‐Jiménez L, López‐Reyes R, López‐Sáez JB, Lorente MA, Lorenzo A, Lumbierres M, Luque JM, Marchena PJ, Martín‐Martos F, Mellado M, Monreal M, Nieto JA, Nieto S, Núñez A, Núñez MJ, Otalora S, Otero R, Pedrajas JM, Pérez G, Pérez‐Ductor C, Peris ML, Pons I, Porras JA, Reig O, Riera‐Mestre A, Riesco D, Rivas A, Rodríguez M, Rodríguez‐Dávila MA, Rosa V, Rosillo‐Hernández E, Ruiz‐Artacho P, Ruiz‐Giménez N, Sahuquillo JC, Sala‐Sainz MC, Sampériz A, Sánchez‐Martínez R, Sanz O, Soler S, Sopeña B, Suriñach JM, Tolosa C, Torres MI, Troya J, Trujillo‐Santos J, Uresandi F, Usandizaga E, Valero B, Valle R, Vela J, Vela L, Vicente MP, Villalobos A, Xifre B, BELGIUM – Vanassche T, Verhamme P, BRAZIL – Yoo HHB, CANADA – Wells P, CZECH REPUBLIC – Hirmerova J, Malý R, Dulíček P, ECUADOR – Salgado E, FRANCE – Bertoletti L, Bura‐Riviere A, Farge‐Bancel D, Hij A, Mahé I, Merah A, Moustafa F, ISRAEL – Braester A, Brenner B, Tzoran I, ITALY – Antonucci G, Barillari G, Bilora F, Bortoluzzi C, Brandolin B, Bucherini E, Cattabiani C, Ciammaichella M, Dell'Elce N, Dentali F, Di Micco P, Duce R, Giorgi‐Pierfranceschi M, Grandone E, Imbalzano E, Lessiani G, Maida R, Mastroiacovo D, Pace F, Parisi R, Pellegrinet M, Pesavento R, Pinelli M, Poggio R, Prandoni P, Quintavalla R, Rocci A, Tiraferri E, Tonello D, Tufano A, Visonà A, LATVIA – Gibietis V, Skride A, Vitola B, REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA – Bosevski M, Zdraveska M, SWITZERLAND – Bounameaux H, Mazzolai L.

Moustafa F, Pierfranceschi MG, Micco PD, et al.; the RIETE Investigators . Clinical outcomes during anticoagulant therapy in fragile patients with venous thromboembolism. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2017;1:172–179. 10.1002/rth2.12036

Funding information

The sponsors of the study (Sanofi and Bayer) had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

[Article updated on September 15, 2017, after first online publication on September 4, 2017: The table within Figure 1 has been updated so that the columns reflect number of days, not months.]

Contributor Information

Farès Moustafa, Email: fmoustafa@chu-clermontferrand.fr.

the RIETE Investigators:

Hervé Decousus, Paolo Prandoni, Benjamin Brenner, Raquel Barba, Laurent Bertoletti, Inna Tzoran, Abilio Reis, Marijan Bosevski, Henri Bounameaux, Radovan Malý, Philip Wells, Manolis Papadakis, MD Adarraga, P Agudo, MA Aibar, M Alfonso, JI Arcelus, A Ballaz, R Barba, M Barrón, B Barrón‐Andrés, J Bascuñana, A Blanco‐Molina, I Cañas, I Casado, N Chic, R del Pozo, J del Toro, MC Díaz‐Pedroche, JA Díaz‐Peromingo, C Falgá, C Fernández‐Aracil, C Fernández‐Capitán, MA Fidalgo, C Font, L Font, P Gallego, MA García, F García‐Bragado, O Gavín, C Gómez, V Gómez, J González, E Grau, A Grimón, R Guijarro, L Guirado, J Gutiérrez, G Hernández‐Comes, L Hernández‐Blasco, L Jara‐Palomares, MJ Jaras, D Jiménez, J Jiménez, MD Joya, P Llamas, JL Lobo, P López, L López‐Jiménez, R López‐Reyes, JB López‐Sáez, MA Lorente, M Lumbierres, JM Luque, PJ Marchena, F Martín‐Martos, M Mellado, S Nieto, A Núñez, MJ Núñez, S Otalora, R Otero, JM Pedrajas, G Pérez, C Pérez‐Ductor, ML Peris, I Pons, JA Porras, O Reig, A Riera‐Mestre, D Riesco, A Rivas, M Rodríguez, MA Rodríguez‐Dávila, V Rosa, E Rosillo‐Hernández, P Ruiz‐Artacho, N Ruiz‐Giménez, JC Sahuquillo, MC Sala‐Sainz, R Sánchez‐Martínez, O Sanz, S Soler, B Sopeña, JM Suriñach, C Tolosa, MI Torres, J Troya, J Trujillo‐Santos, F Uresandi, E Usandizaga, R Valle, J Vela, L Vela, MP Vicente, B Xifre, T Vanassche, P Verhamme, HHB Yoo, P Wells, J Hirmerova, R Malý, P Dulíček, E Salgado, L Bertoletti, A Bura‐Riviere, D Farge‐Bancel, A Hij, I Mahé, A Merah, A Braester, B Brenner, I Tzoran, G Antonucci, G Barillari, F Bilora, C Bortoluzzi, B Brandolin, C Cattabiani, M Ciammaichella, N Dell'Elce, F Dentali, R Duce, E Grandone, E Imbalzano, G Lessiani, R Maida, D Mastroiacovo, F Pace, R Parisi, M Pellegrinet, R Pesavento, M Pinelli, R Poggio, P Prandoni, R Quintavalla, A Rocci, E Tiraferri, D Tonello, A Tufano, A Visonà, V Gibietis, A Skride, B Vitola, M Bosevski, M Zdraveska, H Bounameaux, and L Mazzolai

REFERENCES

- 1. Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al.; RE‐COVER Study Group . Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2342–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al.; AMPLIFY Investigators . Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, et al.; EINSTEIN Investigators . Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Büller HR, Prins MH, Lensin AWA, et al.; EINSTEIN‐PE Investigators . Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1287–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Büller HR, Décousus H, Grosso MA, et al.; Hokusai‐VTE Investigators . Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1406–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:315–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prins MH, Lensing AW, Bauersachs R, et al.; EINSTEIN Investigators . Oral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism: a pooled analysis of the EINSTEIN‐DVT and PE randomized studies. Thromb J. 2013;11:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Y, Wang C, Chen Z, et al. Rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic deep‐vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in Chinese patients: a subgroup analysis of the EINSTEIN DVT and PE studies. Thromb J. 2013;11:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Muriel A, Jiménez D, Aujesky D, et al.; RIETE Investigators . Survival effects of inferior vena cava filter in patients with acute symptomatic venous thromboembolism and a significant bleeding risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1675–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farge D, Trujillo‐Santos J, Debourdeau P, et al.; RIETE Investigators . Fatal events in cancer patients receiving anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiménez D, De Miguel‐Díez J, Guijarro R, et al. Trends in the management and outcomes of acute pulmonary embolism analysis from the RIETE registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:162–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muñoz‐Torrero JFS, Bounameaux H, Pedrajas JM, et al.; Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad TromboEmbólica (RIETE) Investigators . Effects of age on the risk of dying from pulmonary embolism or bleeding during treatment of deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:26S–32S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tzoran I, Brenner B, Papadakis M, Di Micco P, Monreal M. VTE Registry: what can be learned from RIETE? Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2014;5:e0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ruíz‐Giménez N, Suárez C, González R, et al. Predictive variables for major bleeding events in patients presenting with documented acute venous thromboembolism. Findings from the RIETE Registry. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buchner DM, Wagner EH. Preventing frail health. Clin Geriatr Med. 1992;8:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robinson TN, Eiseman B, Wallace JI, et al. Redefining geriatric preoperative assessment using frailty, disability and co‐morbidity. Ann Surg. 2009;250:449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer L, Dunn CL, Cleveland JC, Moss M. Simple frailty score predicts postoperative complications across surgical specialties. Am J Surg. 2013;206:544–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perera V, Bajorek BV, Matthews S, Hilmer SN. The impact of frailty on the utilisation of antithrombotic therapy in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Age Ageing. 2009;38:156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Becattini C, Agnelli G. Treatment of venous thromboembolism with new anticoagulant agents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1941–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuijer PM, Hutten BA, Prins MH, Büller HR. Prediction of the risk of bleeding during anticoagulant treatment for venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:457–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Landefeld CS, Beyth RJ. Anticoagulant‐related bleeding: clinical epidemiology, prediction, and prevention. Am J Med. 1993;95:315–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Landefeld CS, Goldman OL. Major bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin: incidence and prediction by factors known at the start of outpatient therapy. Am J Med. 1989;87:144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Landefeld CS, Cook EF, Flatley M, Weisberg M, Goldman L. Identification and preliminary validation of predictors of major bleeding in hospitalized patients starting anticoagulant therapy. Am J Med. 1987;82:703–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nieto JA, Solano R, Ruiz‐Ribo MD, et al. Fatal bleeding in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism: findings from the RIETE registry. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smythe MA, Priziola J, Dobesh PP, Wirth D, Cuker A, Wittkowsky AK. Guidance for the practical management of the heparin anticoagulants in the treatment of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:165–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Merli G, Spiro TE, Olsson CG, et al. Subcutaneous enoxaparin once or twice daily compared with intravenous unfractionated heparin for treatment of venous thromboembolic disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee AYY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al. Low‐molecular‐weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]