To the Editor

RAG deficiency has an estimated disease incidence of 1:181,000 including severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) at a rate of 1:330,000.1, 2 Complete or hypomorphic variants of SCID secondary to low recombinase activity (<5%) present early with severe infections and/or clinical signs of systemic inflammation, such as severe dermatitis and/or colitis.3, 4 Hypomorphic RAG1/2 mutations with more preserved residual V(D)J recombination activity (5–30%) result in a distinct phenotype of combined immunodeficiency with granuloma and/or autoimmunity (CID-G/A).1, 2, 5 Beyond CID, RAG deficiency has been found in patients with predominantly primary antibody deficiencies6, 7 and naïve CD4+ T cell lymphopenia in most cases. Currently there is no published systematic evaluation for the presence of an underlying RAG deficiency in patients with primary antibody deficiencies. There is great variability among diagnostic modalities for evaluation and treatment for inflammatory lung disease in case reports of RAG deficiency with no standardized guidelines. Clinical features and lung disease for patients with late presentation of RAG deficiency have not been studied extensively. In addition, no studies have examined the prevalence of RAG deficiency in cohorts of adult primary immunodeficiency (PID) patients. Here, we describe a cohort of 15 patients with late presentation of RAG deficiency. We also estimate the prevalence of RAG deficiency in adult PID patents following genetic analysis in two separate large cohorts of PID patients.

We have analyzed the canonical regions of RAG1 and RAG2 in a total of 692 PID patients from two separate cohorts, one from the United Kingdom (UK) and one from Austria (Vienna). The UK cohort is part of the National Institute for Health Research BioResource – Rare Diseases (NIHRBR-RD) PID study, as previously described (Tuijnenburg et al, in revision). In the NIHRBR-RD PID cohort 558 patients (299 adults) and the Vienna cohort of 134 patients (106 adults) we report a total of five newly identified cases of RAG deficiency. For details see repository text E1 and tables E1–3. Based on these findings we estimate that prevalence of RAG deficiency in adult PID ranges from 1%–1.9%. For all adult PID patients that are currently registered with the UK Primary immunodeficiency network database (3294 patients over age of 18 years) we expect to find an additional 32.9–62.6 cases of RAG deficiency. Gene variants are illustrated in Fig 1A. The cohort demographics are discussed in repository text E1.

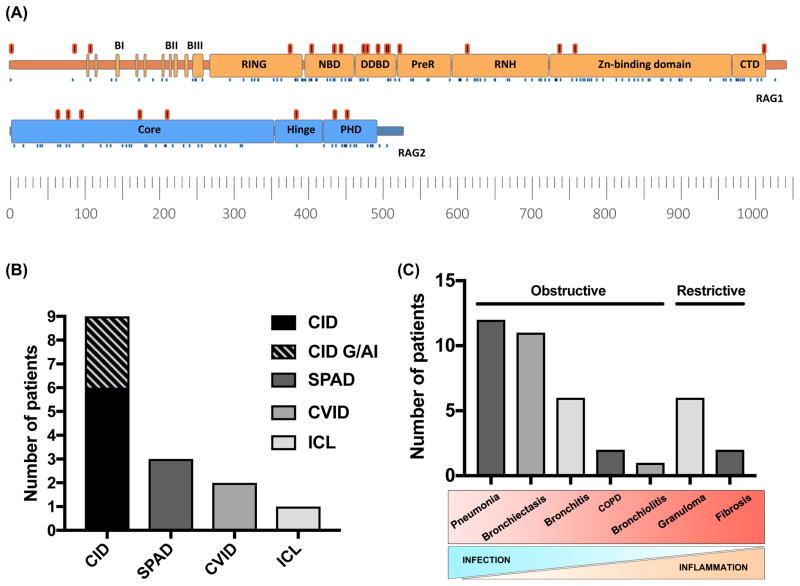

Figure 1. Gene variants and phenotypes of adults with RAG deficiency.

(A) Schematic representation of RAG1 and RAG2 adapted from Notarangelo et al. 2016 (ref E19). Variants in this cohort (17 in RAG1 and 8 in RAG2) are illustrated in red. Known pathogenic variants previously reviewed are shown as blue dots (ref E19). (B) The phenotypes of RAG deficiency in 15 patients including those from the NIHRBR-RD PID and Vienna cohort. (C) Presentation of lung disease. Bars represent age distribution, lines indicate median onset of lung disease, mean age of death, mean age (n=15).

Functional characterization of novel RAG variants is discussed in repository text E1. The activity of mutant RAG1 and RAG2 proteins normally required for catalyzing V(D)J recombination events are shown in Table E2. In addition to the method previously described,8 we also employed a system to measure recombination activity in compound heterozygous cases by in vitro expression of murine RAG1 and RAG2. Both systems simulate the efficiency of protein expressed in patients in their ability to produce a diverse repertoire of TCR and BCR coding for immunoglobulins. Over half of the mutant proteins tested show almost complete loss of activity. All patients tested had an overall low combined RAG activity (6.4–28%).

The immune phenotypes and clinical diagnoses are shown in Fig 1B. Persistently low IgG and/or low IgA and IgM levels are seen in approximately 50% of cases (Table E3). The dominant laboratory features were naïve CD4+ T cell lymphopenia with low absolute number and fraction of naïve CD4 cells (CD4+CD45RA+), and B cell counts were variably low (Table E3). Enzyme-linked immunoassay was used to test for anti-cytokine antibodies (targeting IFNα, ω, and IL-12) on plasma from seven patients (not shown). Four patients were positive which is comparable to our previously reported cohort (56%).5

Most adult RAG deficient patients developed inflammatory autoimmune complications (87%) (Fig E1A, repository text E1). Organ-specific manifestations were most common (73%) and similar to previously described reports of 48–77%.5, 9 Granulomatous disease was seen in 40% of patients, with five out of six patients showing granuloma localization within interstitial lung tissue. Other complications were also seen (Fig E1E). Similar to recent reports (21–77%)5, 9 cytopenias occurred in 40% of patients; autoimmune hemolytic anemia (27%), immune thrombocytopenic purpura (20%), and autoimmune neutropenia in one patient.

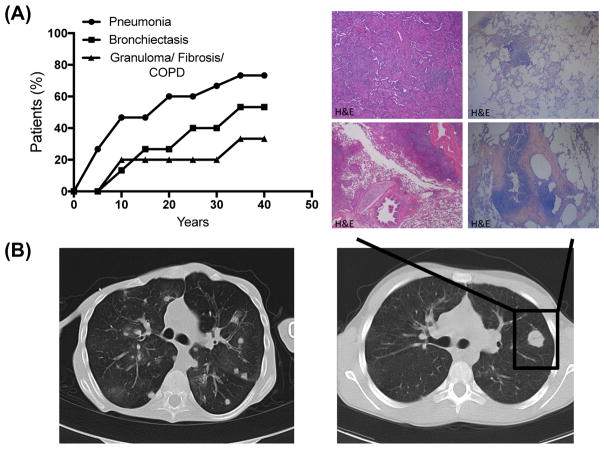

Progressive pulmonary disease was the leading causes of morbidity and mortality (93%) (Fig E1D); pneumonia being the most common, followed by bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, granuloma, fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and bronchiolitis (Fig 1C). We observed a transition from acute infectious complications (pneumonia) (mean onset 14 years) to chronic inflammatory complications (mean age of 23 years) (Fig 2A). It was also the leading concern for successful HSCT. High-resolution computed tomography imaging of lung revealed bronchiectasis and granuloma. Histology of lung biopsies (patient 1 and 3) revealed atypical lymphoid hyperplasia with granulomatous features and giant cells formation (Fig 2B). Germinal center formations in patient 3 were comprised of CD3+ T-cells and CD20+ B-cells. Patient 1 had peribronchial fibrosis (Fig 2B). Pulmonary lung function data revealed median values of FVC 79.55%, DLCO of 75%, and FEV1/FVC ratio of 78%. We performed a retrospective analysis of PFTs over two or more years to assess the decline of respiratory function. Two of four patients had a significant decline indicating a variable degree of lung function in adult patients with RAG deficiency (Fig E1G)(repository text E1).

Figure 2. Pulmonary disease.

(A) Onset of pneumonia, bronchiectasis and granuloma/fibrosis/COPD (n=15). (B) High resolution computed tomography of patient 3 and 9. Histologic examination of lung biopsies from patient 1with atypical lymphoid hyperplasia with granuloma and fibrosis (H&E).

Thirteen out of fourteen patients (93%) received first line immunoglobulin replacement therapy (Fig E1B, Table E2). 57% received antibiotic prophylaxis, 21% antiviral drugs, and 14% disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug. Five patients (36%) were considered for HSCT. Comparisons of therapeutics approaches revealed no statistically significant difference in survival. Three out of eight patients who only received Ig replacement therapy were deceased. Among transplanted patients the major mortality cause was infections post HSCT (Fig E1C).

RAG1/2 are the most common defective genes associated with atypical SCID.9 Patients may survive into adulthood and our findings suggests that prevalence of such cases varies between 1%–1.9% in adult PID cohorts. Total and naïve CD4+ T cell lymphopenia,4, 9 autoimmunity, and progressive inflammatory lung disease should all prompt further investigations for RAG deficiency in adult PID patients. The relative absence of RAG deficiency in the pediatric cohort of 216 patients suggest that milder forms of RAG deficiency may not be diagnosed as readily as a PID in childhood. In the era of whole exome sequencing, the spectrum of RAG deficiency further broadens to include adults with autoimmune and inflammatory manifestations that may result in progressive decline. Systemic analysis of PID related genes8 and functional in vitro assays that confirm decreased recombination activity are essential. Laboratory features of naïve CD4+ T cell lymphopenia and presence of anti-cytokine antibodies can further support the diagnosis of partial RAG deficiency. Where RAG deficiency is confirmed, therapy may be adjusted based on the mechanistic understanding and may ultimately provide targeted strategy for early intervention.

II. Methods

A. Whole genome sequencing

As part of the NIHR BioResource – Rare Disease study, 558 unrelated PID patients had their genomes sequenced, as described before (Tuijnenburg et al, in revision). Briefly, paired-end whole genome sequencing was performed by Illumina on their HiSeq X Ten system, and 95% of bases were covered by at least 15 reads. Substitutions and InDels up to 50bp were called by Isaac and then merged with AGG3 tool, while structural variants were called by Manta and Canvas (all software by Illumina). Only variants with an overall pass rate of >80% and were considered for further analysis. Structural variants were analysed for gene deletions, but none were identified.

B. Targeted sequencing

The canonical region of RAG1 and RAG2 in 134 patients was analyzed. Genomic DNA was prepared from peripheral blood by spin column purification (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit; QIAGEN, Germany). Targeted resequencing of the canonical region of RAG1 and RAG2 was performed using Nextera Custom Enrichment kit according to standard protocols (Illumina, USA). DNA library was quantified and validated using Illumina Eco Realtime (Illumina; USA) and Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies; USA). The library was sequenced in a multiplex pool on a single (150 bp paired-end reads) flowcell on the Miseq System. (Illumina, USA)

C. Variant filtration

PID cohorts were assessed for the region of RAG1 and RAG2; GRCh37 11:36,587,900–36,621,100. Filtering and prediction of functional consequences was performed using Variant Effect Predictor (http://www.ensembl.org/info/docs/tools/vep/index.html), Exome Variant Server (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), The Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/) and ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/), The Exome Aggregation Consortium and The Genome Aggregation Database (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org). Filtering of common variations and annotation was performed using vcfhacks (https://github.com/gantzgraf/vcfhacks) and in-house scripts. Candidate variants were required to pass the following filtering conditions: frequency (count/coverage) between 20–100%, according to VEP-annotation at least one canonical transcript is affected with one of the following consequence: variants of the coding sequence, frameshift, missense, protein altering, splice acceptor, splice donor, or splice region; an inframe insertion or deletion; a start lost, stop gained, or stop retained, or according to VEP an ExAC frequency unkown, <=0.01, or with clinical significance ‘path’.

D. Cell culture and transfection

COS-7 cells (fibroblast-like), from African Green Monkey kidney transformed with a mutant SV40 coding for the wild-type T-antigen, were used for recombination assays. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco). Cells were seeded at 1.5×105 per well (6 well plate) in 1.5ml culture medium 24 hours prior to transfection. Antibiotic free medium was substituted three hours prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with wild type or mutant form of murine RAG1, RAG2 and recombination plasmids using 5uL Lipofectamine™ 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) and 300 uL Opti-MEM® I reduced serum medium (Gibco). Experiments use a total concentration of 400 ng/μL RAG1 construct, 200 ng/μL RAG2 construct, and 1000 ng/μL of inversion recombination substrate. Experiments testing compound heterozygous mutations used half concentrations of both alleles for RAG1 or RAG2.

E. RAG1, RAG2 and recombination substrate plasmids

Mammalian expression plasmids were constructed to contain either murine RAG1 (3192bp in 4350bp pCS2-MT) or RAG2 (1581bp in 5509bp pEF-XC). Site directed mutagenesis was used to produce mutant plasmids using Q5® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits (New England Biolabs, UK). Transfection assays used a combination of wild type or mutant RAG1 and RAG2 plasmids to reflect those of patient genotypes. A third plasmid was constructed and used in each transfection assay as an inversion recombination substrate (6009bp). The site targeted by the RAG1/RAG2 complex is a 557 nucleotide inversion sequence flanked with the 12 and 23 nucleotide RSS; CACAGTGCTACAGACTGGAACAAAAACC and CACAGTGGTAG TACTCCACTGTCTGGCTGTACAAAAACC, respectively (12 and 23 bp spacers with heptamer and nonamer flanking sequences).

F. Recombination assay

Triple-transfection of WT/mutant RAG1/RAG2 and a recombination substrate was used to assess the functional activity matching that of patients with homozygous or compound heterozygous genotypes. Transfection assays used a combination of RAG1 (400 ng/uL) co-transfected with RAG2 (200 ng/uL). Homozygous expression of a mutant gene was mimicked by co-transfecting a RAG1 mutant with wild type RAG2 and vice versa. To mimic compound heterozygous genotypes two equal half concentrations of mutant RAG1 plasmids were co-transfected with wild type RAG2 and vice versa. (i.e.200ng/uL WT RAG1, 200ng/uL mutant RAG1, and 200ng/uL WT RAG2). To measure the activity of these wild type or mutant proteins a third (or fourth in compound heterozygous instances) construct was used as an inversion recombination substrate (1000 ng/μL). The DNA sites targeted on this recombination substrate by RAG1/RAG2 complex are 12 and 23 nucleotide recombination signal sequences (RSS) flanking a 557 nucleotide inversion sequence. Successful recombination events, represented by a reversal of inversion sequence, were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using comparative CT (ΔΔCT) (supplemental Fig E1H). qPCR primer sites were selected on the recombination substrate plasmid at 48 bp upstream of the 12RSS, prior to the inversion sequence, and a primer site 46 upstream of the of the 23RSS, laying internally on the inversion sequence, with both in the forward direction. A successful recombination event resulted in the reverse of inversion sequence and allows amplification of a 94 bp product. A second sequence of 94 bp on the recombination plasmid backbone, which is not affected by RAG activity, was used as a reference to calculate ΔΔCT values and assess relative recombination activity. The relative recombination activity is measured against wild type RAG1/RAG2 to calculate the activity % of WT with mean ± SEM shown in Table 1.

G. Quantitative real-time PCR

Successful recombination events were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using comparative CT (ΔΔCT). To recover recombination plasmid a modified Hirt’s cell lysis extraction for low molecular weight DNA was performed before a phenol chloroform extraction (Thermo Fischer Scientific, 17909) and ethanol precipitation. DNA was diluted 50 times and Fast SYBR® Green Master Mix was used for qPCR. Experiments were performed on a QuantStudio® 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fischer Scientific, 4385610 and A28573).

H. Laboratory evaluation of immune phenotypes

Lymphocyte panel and immunoglobulin levels were determined by clinical laboratory testing. Anti-cytokine antibodies were detected by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) as previously described.1

III. Discussion

Recombination-activating gene 1 (RAG1) and RAG2 encode lymphoid-specific proteins that are essential for V(D)J recombination and diversification the T and B cell repertoire in the thymus and bone marrow, respectively.2, 3 Hypomorphic RAG1/2 mutations with residual V(D)J recombination activity (in average 5–30%) result in a distinct phenotype of combined immunodeficiency with granuloma and/or autoimmunity (CID-G/A).1, 4–8 Currently there is no published systematic evaluation for the presence of an underlying RAG deficiency in patients with primary antibody deficiencies. Inflammatory complications are increasingly reported for RAG deficient patients with CID-G/AI phenotype and late diagnosis.9–11 Allograft rejection and fatal post-transplant complications are more common among SCID patients with RAG variants than in other forms of SCID, especially if harboring infections.12–14 In a recent multicenter study, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was offered in 61% of cases, less frequently than in variants of SCID.1 CID-G/AI patients may also fail to engraft stem cells or die from other post-transplant complications.1, 9, 11, 15

The UK cohort, part of the NIHRBR-RD PID study, included 558 cases with an antibody deficiency, 299 patients presented as adults; CVID were the largest group (n=305), followed by CID (n=101), and other antibody deficiencies (n=78). We report here only coding variants in RAG1 and RAG2; variants identified in non-coding regions were not expected to affect protein expression or function. There were no instances where a patient had a damaging mutation in both RAG1 and RAG2. Other known causes of PID were also excluded in these three patients. The Vienna cohort investigated 134 patients, including 106 adults; CVID (n=57), CID/late onset CID (LOCID) (n=36), primary antibody disorders (PAD) (including hypogammaglobinemia, selective PAD (SPAD) and agammaglobulinemia (n=41). In total five cases of RAG deficiency were identified and are reported in our study. Although these patients were primarily diagnosed with antibody deficiency, closer examination of the T cell compartment revealed low absolute number of naïve CD4 fraction (CD4+CD45RA+) suggestive of a CID phenotype (Table E3).

Complete data was collected for ten additional cases (>15 years of age) (Fig 1, Table E1–3). Of the fifteen patients described here the median age is 37 years (15–73 years), with five patients already deceased at ages 15, 22, 25, 37, and 43 (Table 1, 2). Clinical phenotype was predominantly CID (n=9, 60%), of whom three had clinical history of autoimmunity and/or the presence of granulomas, followed by SPAD (3 patients, 20%), CVID (2 patients, 13%), and a single case of idiopathic CD4+ lymphopenia (ICL) (7%) (Table E1, Fig 1B). Most had late presentation. Although recurrent infections and lung disease were commonly seen in adolescence, severe disease and PID diagnosis generally occurred in adulthood.

Variants found in patients 1–10 were assessed as previously described.16 The variants identified from patients 12–15 were assessed with in vitro expression of murine RAG1 and RAG2 in CV-1 in Origin with SV40 genes cells. The relative recombination activity was measured against wild type RAG1/RAG2 to calculate the activity % of WT with mean ± SEM shown in Table 1. Both systems simulate the efficiency of protein expressed in patients in their ability to produce a diverse repertoire of TCR and BCR coding for immunoglobulins. As shown in Table E2 the mutations found in patients 12–14 have been tested by Lee et al. 26 and show very similar levels of recombination activity for individual mutations.16 Over half of the mutant proteins tested show almost complete loss of activity. Patients 3, 5, 12, 13, and 15 all carry one allele with mutations that individually do not indicate any major loss of function. However, in our assay, we also had the ability to measure recombination activity in compound heterozygous cases and found a striking decrease that was less than the average activity of the two alleles in Patient 12, 13 and 15 (Table E1). All patients tested in our cohort had an overall low combined RAG activity (6.4–28%).

Inflammatory autoimmune complications developed in 87% of patients (Fig E1A). Organ-specific manifestations were the most common autoimmune complications affecting 73% of our adult cohort, similar to previously described reports with 48–77%.1, 17 Gastrointestinal complications were the most prevalent organ specific manifestation followed by dermatological manifestations (Fig E1E). Granulomatous disease was seen in 40% of patients, with five out of six patients showing granuloma localization within interstitial lung tissue. Other complications included myopathies (14%), endocrine abnormalities, sarcoidosis, and polyarthritis was seen in one patient (Fig E1E). Cytopenias occurred in 40% of adult RAG deficient patients (Fig E1A), similar to recently reported cohorts (21–77%).1, 17 Autoimmune hemolytic anemia was the most frequent (27%) followed by immune thrombocytopenic purpura (20%), and autoimmune neutropenia in one patient. Further studies may determine the underlining pathophysiology that drives autoimmunity in RAG deficient patients. 57% of the patients developed antibodies to cytokines, which may serve as a potential biomarker for adults with PID due to RAG1 and/or RAG2 mutations1 (Table E3). It was recently demonstrated, that RAG deficient patients show a restriction of Treg repertoire diversity and a molecular signature of self-reactive conventional CD4+ T cells.18

Progressive pulmonary disease was prominent in our cohort of adults with RAG deficiency (Fig E1D). Of fifteen unrelated adult patients recruited, the median age at onset of lung disease was 11 years. The five patients (33%) that were deceased at the time of the study had a median age of 23.5 years (Fig E1D). We observed a diverse spectrum of pulmonary manifestations (Fig 1C). Clinical symptoms persisted for an average of 13 years. Lung disease was the leading cause of mortality. Of the five deceased patients two cases were due to progressive lung disease with pulmonary fibrosis. Two more patients died due to infections post-transplant. One patient died due to PML caused by John Cunningham virus infection. There was no significant difference in overall survival between patients presenting with pneumonia, bronchiectasis or granuloma, fibrosis, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Computed tomography imaging revealed bronchiectasis and granuloma. Histology of lung biopsies are shown in Fig 2B. A retrospective analysis of PFTs indicated a variable degree of lung function (Fig E1G). Based on literature searches there are only four additional cases of similar adults.1, 4, 5, 7 Of these four, two have died and two had a history of severe lung disease. To promote early intervention, we recommend high resolution chest CT every 1–3 years for signs of progressive pulmonary disease. Treatment of choice should be tailored to both infectious and inflammatory components.

Phenotype-genotype correlations are reported for regions of RAG1 and RAG2.19 Pathogenic missense variants in RAG1 most frequently occur in the catalytic core (amino acids 387–1,011) (Fig 1A), predominantly in the zinc-binding domain. When normalized for domain length, a higher pathogenic variant rate is observed in the NBD and CTD.19 Forty percent of RAG1 patients reported here have disease-causing variants in NBD or CTD. These two domains constitute the highest reported pathogenic mutation rates.19 A few RAG1 missense mutations are associated with CID–G/AI. These variants are predominantly located in the domains DDBD, PreR and CTD.19 Deviation from the phenotype-genotype correlation is illustrated by three patients found to have CID-G/AI; patient 3 (Table E1 and Fig E1F) was found to have compound heterozygous RAG1 mutations in non-core and the catalytic RNase H (RNH) domain while presenting with CID-G/AI, and patients 6 and 7 (Table E1) reported as CID-G/AI due to compound heterozygous core/plant homeodomain (PHD) and homozygous core RAG2 mutations, respectively. Fig 1A, E1F illustrates the distribution of mutations reported in this study amongst RAG1 and RAG2 functional domains.

Newborn screening for SCID and related conditions has identified RAG1/2 as the most common defective genes associated with atypical SCID17, 20 Based on ExAC data analysis, we predicted the incidence of RAG deficiency as 1:181,000 individuals who are homozygous or compound heterozygous for pathogenic RAG1/2 mutations.7 Furthermore, based on two large cohort studies in Europe, we provide an estimate for the prevalence of RAG deficiency in adult PID between 1%–1.9%. With this estimate we expect to find an additional 32.9–62.6 cases of RAG deficiency in the UKPIN database. A robust systemic analysis of 79 individual mutations in RAG1 was conducted previously.16 Our results were comparable to the published data.16 Furthermore, we assessed activity levels in RAG1 and RAG2 compound heterozygous cases and found lower activity levels than the average of activity levels when each allele was measured separately. The relative absence of RAG deficiency in the pediatric cohort of 216 patients suggest that milder forms of RAG deficiency may not be diagnosed as readily as a PID in childhood. The low number of naïve CD4 cells may appear as idiopathic T cell lymphopenia subset when screened at birth.21 Careful analysis of HSCT decision is needed and should be considered before onset of rapid or progressive decline in lung function.15, 22 Interim analysis has been provided to guide difficult HSCT decisions for patients with SCID and profound CID.17, 20 Patients with more severe phenotypes generally have a progressively pronounced restriction of their BCR and TCR repertoire diversity. Analysis of the TCR and BCR repertoire identifies skewed usage of V(D)J segment genes and abnormalities of CDR3 length distribution.23 We also see, as recently published24, that low IgA and IgM is associated with bronchiectasis in PID. Mutant RAG1 and RAG2 proteins with residual recombination activity in these patients likely provides antibody repertoire that may be sufficient during early childhood but immunodeficiency and progressive autoimmunity becomes apparent towards early adolescence. Phenotypic heterogeneity impedes prediction of the clinical phenotype, although at least 150 and 57 disease-causing variants which are likely to result in clinical intervention are reported for RAG1 and RAG2, respectively.19

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study makes use of data generated by the NIHR BioResource - Rare Disease Consortium; A full list of the consortium members who contributed to the generation of the data is available in supplemental materials. Funding for the project was provided by the National Institute for Health Research (grant number RG65966). This work was also funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. We thank Prof Christian J. Müller for providing pathology specimens and Dr. Karl Waibel for providing pulmonary function testing.

Abbreviations

- AB

antibiotics

- AIC

Autoimmune cytopenia

- AIHA

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- AN

Autoimmune neutropenia

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- BCR

B cell receptor

- CID

Combined immune deficiency

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COS-7

CV-1 in Origin with SV40 genes

- CT

computed tomography

- CTD

carboxy-terminal domain

- CVID

Common variable immunodeficiency

- CXR

chest x-ray

- DDBD

dimerization and DNA-binding domain

- G/AI

granulomatous/autoimmune

- HRCT

high-resolution computed tomography

- HSCT

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- HYPOGAM

Hypogammaglobinemia

- ICL

Idiopathic CD4+ T lymphopenia

- ITP

Immune thrombocytopenia

- IVIG

Intravenous immunoglobulin

- MODS

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

- NBD

nonamer-binding domain

- NIHR

National Institute for Health Research

- PFT

pulmonary function test

- PHD

plant homeodomain

- PID

Primary immunodeficiency

- PreR

pre-RNase H

- RAG

Recombination-activating gene

- RNH

RNase H

- RSS

Recombination signal sequence

- SCIG

subcutaneous immunoglobulin

- SPAD

Specific polysaccharide antibody deficiency

- TCR

T cell receptor

- V(D)J

Variable, diversity, and joining

- ZnBD

zinc-binding domain.

The members of the NIHR BioResource – Rare Diseases PID Consortium

Zoe Adhya, Hana Alachkar, Ariharan Anantharachagan, Richard Antrobus, Gururaj Arumugakani, Chiara Bacchelli, Helen Baxendale, Claire Bethune, Shahnaz Bibi, Barbara Boardman, Claire Booth, Michael Browning, Mary Brownlie, Siobhan Burns, Anita Chandra, H. Clifford, Nichola Cooper, E.G. Davies, Sophie Davies, John Dempster, Lisa Devlin, Rainer Doffinger, Elizabeth Drewe, David Edgar, William Egner, Tariq El-Shanawany, Bobby Gaspar, Rohit Ghurye, Kimberley Gilmour, Sarah Goddard, Pavel Gordins, Sofia Grigoriadou, Scott Hackett, Rosie Hague, Lorraine Harper, Grant Hayman, Archana Herwadkar, Stephen Hughes, Aarnoud Huissoon, Stephen Jolles, Julie Jones, Peter Kelleher, Nigel Klein, Taco Kuijpers (PI), Dinakantha Kumararatne, James Laffan, Hana Lango Allen, Sara Lear, Hilary Longhurst, Lorena Lorenzo, Jesmeen Maimaris, Ania Manson, Elizabeth McDermott, Hazel Millar, Anoop Mistry, Valerie Morrisson, Sai Murng, Iman Nasir, Sergey Nejentsev, Sadia Noorani, Eric Oksenhendler, Mark Ponsford, Waseem Qasim, Ellen Quinn, Isabella Quinti, Alex Richter, Crina Samarghitean, Ravishankar Sargur, Sinisa Savic, Suranjith Seneviratne, Carrock Sewall, Fiona Shackley, Ilenia Simeoni, Kenneth Smith (PI), Emily Staples, Hans Stauss, Cathal Steele, James Thaventhiran, Moira Thomas, Adrian Thrasher (PI), Steve Welch, Lisa Willcocks, Sarita Workman, Austen Worth, Nigel Yeatman, Patrick Yong.

The members of the NIHR BioResource – Rare Diseases Management Team

Sofie Ashford, John R Bradley, Debra Fletcher, Tracey Hammerton, Roger James, Nathalie Kingston, Willem H Ouwehand, Christopher J Penkett, F Lucy Raymond, Kathleen Stirrups, Marijke Veltman, Tim Young.

The members of the NIHR BioResource – Rare Diseases Enrolment and Ethics Team

Sofie Ashford, Matthew Brown, Naomi Clements-Brod, John Davis, Eleanor Dewhurst, Marie Erwood, Amy Frary, Rachel Linger, Jennifer Martin, Sofia Papadia, Karola Rehnstrom

The members of the NIHR BioResource – Rare Diseases Bioinformatics Team

William Astle, Antony Attwood, Marta Bleda, Keren Carss, Louise Daugherty, Sri VV Deevi, Stefan Graf, Daniel Greene, Csaba Halmagyi, Matthias Haimel, Fengyuan Hu, Roger James, Hana Lango Allen, Vera Matser, Stuart Meacham, Karyn Megy, Christopher J Penkett, Olga Shamardina, Kathleen Stirrups, Catherine Titterton, Salih Tuna, Ernest Turro, Ping Yu, Julie von Ziegenweldt.

The members of the Cambridge Translational GenOmics Laboratory

Abigail Furnell, Rutendo Mapeta, Ilenia Simeoni, Simon Staines, Jonathan Stephens, Kathleen Stirrups, Deborah Whitehorn, Paula Rayner-Matthews, Christopher Watt.

Further information is available from https://bioresource.nihr.ac.uk/rare-diseases/consortia-lists/

Footnotes

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients gave their written informed consent that anonymized data could be included in a scientific publication. All results presented in this study were obtained as part of the routine medical attendance the patient received.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: Dr. Jolan Walter has received federal funding. This work was partly supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH grant 5K08A1103035 (J.E.W.), Jeffrey Modell Foundation (J.E.W.), Robert A. Good Endowment, University of South Florida, USA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kumanovics A, Lee YN, Close DW, Coonrod EM, Ujhazi B, Chen K, et al. Estimated disease incidence of RAG1/2 mutations: A case report and querying the Exome Aggregation Consortium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwan A, Abraham RS, Currier R, Brower A, Andruszewski K, Abbott JK, et al. Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency in 11 screening programs in the United States. JAMA. 2014;312:729–38. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwarz K, Gauss GH, Ludwig L, Pannicke U, Li Z, Lindner D, et al. RAG mutations in human B cell-negative SCID. Science. 1996;274:97–9. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felgentreff K, Perez-Becker R, Speckmann C, Schwarz K, Kalwak K, Markelj G, et al. Clinical and immunological manifestations of patients with atypical severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol. 2011;141:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter JE, Rosen LB, Csomos K, Rosenberg JM, Mathew D, Keszei M, et al. Broad-spectrum antibodies against self-antigens and cytokines in RAG deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2015 doi: 10.1172/JCI80477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchbinder D, Baker R, Lee YN, Ravell J, Zhang Y, McElwee J, et al. Identification of Patients with RAG Mutations Previously Diagnosed with Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:119–24. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0121-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geier CB, Piller A, Linder A, Sauerwein KM, Eibl MM, Wolf HM. Leaky RAG Deficiency in Adult Patients with Impaired Antibody Production against Bacterial Polysaccharide Antigens. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YN, Frugoni F, Dobbs K, Walter JE, Giliani S, Gennery AR, et al. A systematic analysis of recombination activity and genotype-phenotype correlation in human recombination-activating gene 1 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1099–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speckmann C, Doerken S, Aiuti A, Albert MH, Al-Herz W, Allende LM, et al. A prospective study on the natural history of patients with profound combined immunodeficiency: An interim analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1302–10. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Walter JE, Rosen LB, Csomos K, Rosenberg JM, Mathew D, Keszei M, et al. Broad-spectrum antibodies against self-antigens and cytokines in RAG deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2015 doi: 10.1172/JCI80477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schatz DG, Oettinger MA, Baltimore D. The V(D)J recombination activating gene, RAG-1. Cell. 1989;59:1035–48. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90760-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oettinger MA, Schatz DG, Gorka C, Baltimore D. RAG-1 and RAG-2, adjacent genes that synergistically activate V(D)J recombination. Science. 1990;248:1517–23. doi: 10.1126/science.2360047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuetz C, Huck K, Gudowius S, Megahed M, Feyen O, Hubner B, et al. An immunodeficiency disease with RAG mutations and granulomas. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2030–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Ravin SS, Cowen EW, Zarember KA, Whiting-Theobald NL, Kuhns DB, Sandler NG, et al. Hypomorphic Rag mutations can cause destructive midline granulomatous disease. Blood. 2010;116:1263–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-267583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson LA, Frugoni F, Hopkins G, de Boer H, Pai SY, Lee YN, et al. Expanding the spectrum of recombination-activating gene 1 deficiency: a family with early-onset autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:969–71. e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumanovics A, Lee YN, Close DW, Coonrod EM, Ujhazi B, Chen K, et al. Estimated disease incidence of RAG1/2 mutations: A case report and querying the Exome Aggregation Consortium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwan A, Abraham RS, Currier R, Brower A, Andruszewski K, Abbott JK, et al. Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency in 11 screening programs in the United States. JAMA. 2014;312:729–38. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchbinder D, Baker R, Lee YN, Ravell J, Zhang Y, McElwee J, et al. Identification of Patients with RAG Mutations Previously Diagnosed with Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:119–24. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0121-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geier CB, Piller A, Linder A, Sauerwein KM, Eibl MM, Wolf HM. Leaky RAG Deficiency in Adult Patients with Impaired Antibody Production against Bacterial Polysaccharide Antigens. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharapova SO, Migas A, Guryanova I, Aleshkevich S, Kletski S, Durandy A, et al. Late-onset combined immune deficiency associated to skin granuloma due to heterozygous compound mutations in RAG1 gene in a 14 years old male. Hum Immunol. 2013;74:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuetz C, Neven B, Dvorak CC, Leroy S, Ege MJ, Pannicke U, et al. SCID patients with ARTEMIS vs RAG deficiencies following HCT: increased risk of late toxicity in ARTEMIS-deficient SCID. Blood. 2014;123:281–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-476432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pai SY, Cowan MJ. Stem cell transplantation for primary immunodeficiency diseases: the North American experience. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14:521–6. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Villartay JP, Lim A, Al-Mousa H, Dupont S, Dechanet-Merville J, Coumau-Gatbois E, et al. A novel immunodeficiency associated with hypomorphic RAG1 mutations and CMV infection. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3291–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI25178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John T, Walter JE, Schuetz C, Chen K, Abraham RS, Bonfim C, et al. Unrelated Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in a Patient with Combined Immunodeficiency with Granulomatous Disease and Autoimmunity Secondary to RAG Deficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2016;36:725–32. doi: 10.1007/s10875-016-0326-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YN, Frugoni F, Dobbs K, Walter JE, Giliani S, Gennery AR, et al. A systematic analysis of recombination activity and genotype-phenotype correlation in human recombination-activating gene 1 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1099–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Speckmann C, Doerken S, Aiuti A, Albert MH, Al-Herz W, Allende LM, et al. A prospective study on the natural history of patients with profound combined immunodeficiency: An interim analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1302–10. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowe JH, Stadinski BD, Henderson LA, Ott de Bruin L, Delmonte O, Lee YN, et al. Abnormalities of T-cell receptor repertoire in CD4+ regulatory and conventional T cells in patients with RAG mutations: Implications for autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Notarangelo LD, Kim MS, Walter JE, Lee YN. Human RAG mutations: biochemistry and clinical implications. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:234–46. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dvorak CC, Cowan MJ, Logan BR, Notarangelo LD, Griffith LM, Puck JM, et al. The Natural History of Children with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency: Baseline Features of the First Fifty Patients of the Primary Immune Deficiency Treatment Consortium Prospective Study 6901. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:1156–64. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9917-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuijpers TW, Ijspeert H, van Leeuwen EM, Jansen MH, Hazenberg MD, Weijer KC, et al. Idiopathic CD4+ T lymphopenia without autoimmunity or granulomatous disease in the slipstream of RAG mutations. Blood. 2011;117:5892–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobbs K, Tabellini G, Calzoni E, Patrizi O, Martinez P, Giliani SC, et al. Natural Killer Cells from Patients with Recombinase-Activating Gene and Non-Homologous End Joining Gene Defects Comprise a Higher Frequency of CD56bright NKG2A+++ Cells, and Yet Display Increased Degranulation and Higher Perforin Content. Front Immunol. 2017;8:798. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YN, Frugoni F, Dobbs K, Tirosh I, Du L, Ververs FA, et al. Characterization of T and B cell repertoire diversity in patients with RAG deficiency. Science Immunology. 2016:1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aah6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodkinson JP, Bangs C, Wartenberg-Demand A, Bauhofer A, Langohr P, Buckland MS, et al. Low IgA and IgM Is Associated with a Higher Prevalence of Bronchiectasis in Primary Antibody Deficiency. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2017;37:329–31. doi: 10.1007/s10875-017-0381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroder C, Baerlecken NT, Pannicke U, Dork T, Witte T, Jacobs R, et al. Evaluation of RAG1 mutations in an adult with combined immunodeficiency and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Clin Immunol. 2017;179:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.