Abstract

A growing body of literature indicates that childhood emotion regulation predicts later success with peers, yet little is known about the processes through which this association occurs. The current study examined mechanisms through which emotion regulation was associated with later peer acceptance and peer rejection, controlling for earlier acceptance and rejection. Data included mother-, teacher-, and peer-reports on 338 children (55% girls, 68% European American) at ages 7 and 10. A path analysis was conducted to test the indirect effects of emotion regulation at age 7 on peer acceptance and peer rejection at age 10 via positive social behaviors of cooperation and leadership, and negative social behaviors of indirect and direct aggression. Results indicated numerous significant indirect pathways. Taken together, findings suggest cooperation, leadership, and direct and indirect aggression are all mechanisms by which earlier emotion regulation contributes to later peer status during childhood.

Keywords: aggression, emotion regulation, middle childhood, peer acceptance, peer rejection

It has long been recognized that interactions and relationships with peers are important for children’s development and well-being (Dodge, 1983; Hartup, 1964), and therefore researchers have sought to identify predictors of children’s status with peers. Of particular interest are social behaviors that may be associated with peer acceptance or peer rejection, due to the roles of acceptance and rejection in later outcomes (see Prinstein, Rancourt, Guerry, & Browne, 2009 for a review). In contrast, relatively little research has considered emotional predictors of peer status, despite a large body of research that indicates emotional competence is critical to social competence (Calkins, Gill, Johnson, & Smith, 1999; Contreras, Kerns, Weimer, Gentzler, & Tomich, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1993). What little research has been conducted on this link between emotional competence and peer status has focused almost exclusively on early childhood. The current study addresses this gap by bridging two bodies of literature within the developmental time period of middle childhood, a period during which children’s social behavior is becoming more stable and peer relationships are becoming more salient. We propose a process model by which children’s emotion regulation indirectly affects peer acceptance and rejection through the social behaviors of direct aggression, indirect aggression, cooperation, and leadership.

Links from Social Behaviors to Peer Status

The importance of peer interactions and relationships in children’s lives grows substantially as they mature, and with this growth comes increased expectations of more complex social behaviors and norms. By middle childhood and preadolescence, children spend a great deal of time with their peers and begin to use their peers to meet social and personal needs, such as companionship, identity formation, and support (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Hartup & Stevens, 1997). Therefore, mastering social behaviors that attract peers, as well as avoiding behaviors that may repel them, is an important component of social development in this time period. Extant research has shed light on the social behaviors that underlie children’s acceptance and rejection by their peers.

Children who are accepted by peers have a generally positive behavioral profile; they are higher in positive social behaviors, such as cooperation, friendliness, and leadership, and lower in more negative behaviors, such as direct and indirect aggression, disruptiveness, and submissiveness (Asher & McDonald, 2009; Ironsmith & Poteat, 1990; Zeller, Vannatta, Schafer, & Noll, 2003). A recent study examined such associations in middle childhood (Rodkin, Ryan, Jamison, & Wilson, 2013) and found that the social behavior patterns of prosocial behavior and aggression in the fall of the school year predicted peer acceptance at the end of the year, controlling for earlier levels of peer acceptance. Children who were higher in prosocial behavior in the fall were more accepted by peers in the spring, while children who were higher in aggressive behavior in the fall were less accepted by peers in the spring.

Children who are rejected by peers have a generally negative behavioral profile; they are lower in positive social behaviors, such as cooperation, sharing, and empathic responding; and higher in negative social behaviors such as aggression, conflict, and exclusion (Asher & McDonald, 2009; Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990). In one of the few studies to consider both positive and negative social behaviors as correlates of peer rejection, Casiglia, Lo Coco, and Zappulla (1998) found that, among Italian early adolescents, individuals who were higher in peer rejection were lower in peer-nominated positive social behaviors and higher in aggression.

The association between peer status and indirect aggression, which can be defined as behaviors that attempt to inflict harm but avoid detection, such as social manipulation (Bjorkqvist, Lagerspetz, & Kaukianinen, 1992; Lagerspetz, Bjorkqvist, & Peltonen, 1988), has not been well established. A study of Finnish students found that adolescents higher in indirect aggression were rated higher in both peer acceptance and peer rejection (Salmivalli, Kaukiainen, & Lagerspetz, 2000). These results suggest that adolescents who engaged in indirect aggression were both liked and disliked. After controlling for more direct forms of aggression, though, higher levels of indirect aggression were still associated with higher levels of peer acceptance but with lower levels of peer rejection. Results of this study suggest that indirect aggression, without the presence of other types of aggression, may be a particularly successful mechanism for achieving success with peers. These findings highlight the fact that children and adolescents engage in a variety of social behaviors, such as direct and indirect aggression, within the same peer group and these behaviors have unique associations with peer status. This underlies the importance of examining these behaviors in a manner that accounts for their interdependent nature, a point emphasized by other peer relationships researchers (Coie et al., 1990). In the current study, we extend this rationale by accounting for both positive and negative social behaviors in the same analysis.

In sum, the body of literature examining behavioral correlates and predictors of peer status is broad and has identified important patterns of behaviors that lead to success or failure with peers. However, many of these studies are cross-sectional designs that do not consider the ways that children’s previous behaviors and status may shape the associations between behavior and status. Additionally, most studies focus on either peer acceptance or peer rejection, rather than examining both outcomes. Finally, few studies include both positive and negative social behaviors as predictors of peer status. The current study includes both negative social behaviors, direct and indirect aggression, and positive behaviors, cooperation and leadership, that have been identified in prior research as important to peer status during middle childhood. We analyze each of these constructs in a single model in order to better understand the unique effects of each type of social behavior may have on each outcome.

Emotion Regulation and Social Behaviors

Researchers and theorists have recognized the underlying role of emotional competence in the development of social competence for quite some time (Calkins et al., 1999; Eisenberg et al., 1993). Emotion regulation is a complex construct comprised of both automatic and effortful processes that work together to maintain and modulate emotional expression and experience (Calkins & Hill, 2007). These regulatory processes function at a biological, behavioral, and environmental level and are transactional in nature (Calkins, 2011; Sameroff, 2010). Despite the multidimensional nature of emotion regulation, it can be difficult to measure these complexities in middle childhood because the processes through which children regulate become more internalized as children mature and learn more subtle forms of regulation (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002). Therefore, emotion regulation is often measured as others’ perceptions of a child’s ability to manage his or her emotional responses appropriately across a range of situations.

The association between emotion regulation processes and global social competence has been studied extensively, establishing that the ability to effectively regulate emotion contributes to the development of adaptive social functioning (Denham et al., 2003; Eisenberg et al., 1993; Saarni, 1999). However, much less is known about the influence of emotion regulation on specific social outcomes. As children move through middle childhood, peer transactions become more relational and have a greater affective component (Berndt, 1982), which means the ability to modulate emotional arousal is likely to predict children’s ability to maintain positive peer relationships. This hypothesis has been borne out in empirical work (Blair, Perry, O’Brien, Calkins, Keane, & Shanahan, 2014).

The link between emotion regulation and aggression is also well-established (see Röll, Koglin, & Petermann, 2012 for a review). In general, lower levels of emotion regulation and higher levels of negative emotional reactivity are associated with higher levels of direct aggression across early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence (Crockenberg, Leerkes, & Jó, 2008; McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, Mennin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2009). In addition, a handful of studies have examined emotion regulation as a predictor of indirect aggression. This body of literature is somewhat less clear, although it does point to a similar trend of lower levels of regulation associated with higher levels of indirect aggression (Bowie, 2010; Sullivan, Helms, Kliewer, & Goodman, 2010).

Emotion regulation has also been examined as a predictor of positive social behaviors. Regarding cooperation, most studies have focused on early childhood and have found significant positive associations between emotion regulation and cooperation or sharing with peers (Calkins et al., 1999; Ramani, Brownell, & Campbell, 2010). Literature on the role of emotion regulation in childhood leadership is less clear. One correlational study of adolescents found that self-reported emotional intelligence was positively correlated with peer-nominated leadership (Charbonneau & Nichol, 2002). On the other hand, in a study of maltreated and non-maltreated boys and girls in middle childhood, no association was found between emotion regulation and peer-nominated leadership (Shields, Ryan, & Cicchetti, 2001). Additional research is needed to clarify this association.

Emotion Regulation and Peer Status

A growing body of research indicates that preschool children who engage in strong emotional displays, either positive or negative, are likely to be rejected by peers (Hubbard, 2001), as are children who have difficulty regulating emotion (Shin et al., 2011). On the other hand, children who show a high degree of regulatory competence are able to engage with peers more positively and are more likely to be accepted by peers (Spinrad et al., 2006; Trentacosta, & Izard, 2007). Thus, the ability to regulate emotional arousal in a manner that is contextually appropriate is a critical predictor of peer status.

There is reason to believe that social behaviors are likely mechanisms through which emotion regulation shapes children’s success with peers. Rose-Krasnor’s model of social-emotional competence (1997; Rose-Krasnor & Denham, 2009) proposes that emotion regulation is one of the foundational skills that children build on in order to meet social goals, and meeting social goals promotes successful social interactions, and thus shapes peer relationships and status. Arsenio, Cooperman, and Lover (2000) demonstrated that preschool children’s emotional competence was associated with peer acceptance, but this association was mediated by aggressive acts toward peers. Another study tested a similar process model in which emotion knowledge in kindergarten shaped peer acceptance in first grade via children’s social skills (Mostow, Izard, Fine, & Trentacosta, 2002). We extend these prior studies by hypothesizing that positive and negative social behaviors are the mechanisms through which emotion regulation is related to peer status in middle childhood.

Specifically, children who are able to regulate their emotions effectively are in a better position to think critically about their social goals and motivations, select appropriate behavioral responses, and then act to achieve their goals (Eisenberg et al., 1993; Smith, 2001). Therefore, over time, children who are proficient in regulating emotion are likely to accumulate successful experiences of executing positive social behavior for their own social benefit, and this success is likely to motivate such children to utilize positive social behaviors more frequently and more effectively as they transition to preadolescence. In contrast, children who have difficulty regulating their emotions are more likely to engage in negative social behaviors such as aggression, which are ineffective ways of controlling and modulating emotion. In turn, these behaviors are likely to lead to peer rejection.

Current Study

This study aimed to bridge two bodies of literature that are central to current empirical work on social-emotional development: emotion regulation as a predictor of specific social behaviors and social behaviors as correlates of peer status. Thus, we examined a process model by which emotion regulation shapes changes in specific social behaviors, which in turn, are associated with peer acceptance and rejection. Although these associations have been examined independently in previous research, this study represents a first attempt to bring them together into an integrated model, and extends this model into middle childhood. For instance, previous research utilizing the sample of the current study has found that higher levels of problem behaviors in preschool, including low levels of emotion regulation, predicted lower social preference in kindergarten (Keane & Calkins, 2004). This association was mediated by peer-nominated direct aggression for boys and cooperation for girls. Similarly, another study utilizing this sample found that, among kindergarteners, physiological regulation was associated positively with social preference, which was mediated by peer-nominated cooperation (Graziano, Keane, & Calkins, 2007). Thus, the current study extends this previous work by integrating aggression and cooperation into the same model and including additional developmentally appropriate social behaviors as mediators, breaking apart peer acceptance and rejection as outcomes, and examining these processes in middle childhood rather than early childhood.

We examined three sets of hypotheses. The first addresses the longitudinal relation between emotion regulation and social behaviors. We hypothesized that children’s emotion regulation at age 7 would be associated negatively with direct and indirect aggression at age 10, controlling for age 7 direct and indirect aggression. Similarly, we hypothesized that emotion regulation would be associated positively with cooperation and leadership at age 10, controlling for cooperation and leadership at age 7. Our second set of hypotheses concerned the relations between social behavior and peer status. We hypothesized that direct aggression at age 10 would be positively associated with peer rejection at age 10 and cooperation and leadership would be negatively associated with peer rejection at age 10. Similarly, we anticipated that cooperation and leadership would be positively associated with peer acceptance, while direct aggression would be negatively associated with peer acceptance. Given prior literature, we expected indirect aggression to be positively related to both peer rejection and peer acceptance. Finally, in our third set of hypotheses, we hypothesized that emotion regulation would have indirect effects on both peer rejection and peer acceptance through positive and negative social behaviors.

Methods

Recruitment and attrition

The current study utilized data from three cohorts of children who are part of an ongoing longitudinal study of social and emotional development. The goal for recruitment was to obtain a sample of children who were at risk for developing future externalizing behavior problems, and who were representative of the surrounding community in terms of race and socioeconomic status (SES). All cohorts were recruited through child day care centers, the County Health Department, and the local Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program. Potential participants for cohorts 1 and 2 were recruited at 2-years of age (cohort 1: 1994–1996 and cohort 2: 2000–2001) and screened using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 2–3; Achenbach, 1992), completed by the mother, in order to over-sample for externalizing behavior problems. Children were identified as being at-risk for future externalizing behaviors if they received an externalizing T-score of 60 or above. Efforts were made to obtain approximately equal numbers of males and females. This recruitment effort resulted in a total of 307 selected children. Cohort 3 was initially recruited when infants were six-months of age (in 1998) for their level of frustration, based on laboratory observation and parent report, and were followed through the toddler period (see Calkins, Gill, Johnson, & Smith, 1999 for more information). Children from Cohort 3 whose mothers completed the CBCL at 2-years of age (N = 140) were then included in the larger study. Of the entire sample (N = 447), 37% of the children were identified as being at risk for future externalizing problems. There were no significant demographic differences between cohorts with regard to gender, χ2 (2, N = 447) = .63, p = .73, race, χ2 (2, N = 447) = 1.13, p = .57, or 2-year SES, F (2, 444) = .53, p = .59.

Of the 447 originally selected participants, six were dropped because they did not participate in any 2-year data collection. At 7 years of age, 350 families participated. There were no significant differences between families who did and did not participate in terms of gender, χ2 (1, N = 447) = 2.12, p = .15, race, χ2 (3, N = 447) = .19, p = .67, and 2-year externalizing T score, t (445) = 1.30, p = .19. Families with lower 2-year SES, t (432) = −2.61, p < .01, were less likely to participate in the 7-year assessment. At age 10, 357 families participated, including 31 families that did not participate in the 7-year assessment. No significant differences were noted between families who did and did not participate in the 10-year assessment in terms of child gender, χ2 (1, N = 447) = 3.31, p = .07; race, χ2 (3, N = 447) = 3.12, p = .08; 2-year SES, t (432) = .02, p = .98; or 2-year externalizing T score, t (445) = −.11, p = .91.

Participants

The sample for the current study included 338 children (185 girls, 153 boys) who participated in the 7 and 10-year assessments. Children were included in the current study if they had at least one indicator of emotion regulation at age 7. In addition, four participants were dropped from the current study due to developmental delays. Sixty-eight percent of the analytic sample was European American, 27% African American, 4% biracial, and 2% other. Families were economically diverse based on Hollingshead (1975) scores at the 7-year assessment, with a range from 14 to 66 (M = 44.78, SD = 11.78), thus representing families from each level of social strata typically captured by this scale. Hollingshead scores that range from 40 to 54 reflect minor professional and technical occupations considered to be representative of middle class.

Procedures

Children and their mothers participated in an ongoing longitudinal study beginning when the children were 2 years of age. The current analyses include data collected when children were 7 and 10 years of age. At each laboratory visit, mothers completed questionnaires regarding family demographics and their child’s functioning. In addition, teachers were sent questionnaire packets to complete and mail back.

Peer data were collected using a sociometric nomination procedure when children were 7 and 10, second and fifth grades respectively. In second grade, rosters used for nominations were classroom-based, and in fifth grade, they were grade-based. This change occurred because many participants experienced a switch from elementary school to middle school upon entering fifth grade. The change to middle school included a new daily schedule in which students changed classes throughout the day and interacted with many more students in their grade than they would have in elementary school. Thus, this change in data collection protocol reflected an important change in the peer contexts of the participants. Given that participants were originally recruited long before they entered school, they attended many different schools by the time they were in second grade. In second grade, 218 classrooms from 80 schools were included in the data collection, with an average classroom participation rate of 65%. In fifth grade, 465 classrooms from 80 schools were included, with an average of 49 participants per school.

Measures

Emotion regulation.

A latent variable of emotion regulation at age 7 was constructed with mother and teacher reports of children’s emotion regulation when children were 7-years-old using the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). This measure assesses reporters’ perception of the child’s emotionality and regulation and includes 24 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale indicating how frequently the behaviors occur (1 = almost always to 4 = never). The emotion regulation subscale (α = .66; α = .77 for mothers and teachers, respectively) includes eight items that assess children’s control of their emotional responses, while the lability/negativity (15 items, α = .86; α = .91) subscale assesses negative affect and emotional intensity. Example items include, “displays appropriate negative affect in response to hostile, aggressive or intrusive play” and “can say when he/she is sad, angry, mad, fearful, or afraid.” We utilized the two subscales from each reporter as separate indicator variables to create the latent variable of emotion regulation. All four indicators were significantly correlated and in the expected directions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 7y Regulation – MR | -- | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. 7y Regulation – TR | .27 | -- | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. 7y Lability – MR | −.48 | −.35 | -- | |||||||||||||||

| 4. 7y Lability – TR | −.21 | −.55 | .41 | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 5. 7y Direct Agg | −.12 | −.22 | .25 | .47 | -- | |||||||||||||

| 6. 7y Indirect Agg | −.13 | −.25 | .24 | .45 | .66 | -− | ||||||||||||

| 7. 7y Cooperation | .13 | .29 | −.26 | −.46 | −.49 | −.45 | -- | |||||||||||

| 8. 7y Leadership | .08 | .21 | −.23 | −.31 | −.20 | −.17 | .54 | -- | ||||||||||

| 9. 10y Direct Agg | −.14 | −.04 | .23 | .33 | .51 | .40 | −.21 | −.14 | -- | |||||||||

| 10. 10y Indirect Agg | −.05 | −.07 | .20 | .22 | .21 | .21 | .03 | .01 | .52 | -− | ||||||||

| 11. 10y Cooperation | .24 | .34 | -.32 | −.49 | −.49 | −.40 | .53 | .39 | −.45 | −.21 | -- | |||||||

| 12. 10y Leadership | .14 | .32 | −.25 | −.37 | −.15 | −.13 | .47 | .46 | −.04 | .06 | .57 | -- | ||||||

| 13. 7y Peer Acceptance | .06 | .23 | −.19 | −.28 | −.29 | −.27 | .60 | .52 | −.08 | .04 | .40 | .40 | -- | |||||

| 14. 7y Peer Rejection | −.13 | −.20 | .32 | .32 | .52 | .46 | −.52 | −.42 | .25 | .05 | −.47 | −.34 | −.62 | -- | ||||

| 15. 10y Peer Acceptance | .08 | .20 | −.25 | .22 | −.22 | −.10 | .38 | .33 | −.15 | .04 | .50 | .49 | .36 | −.32 | -- | |||

| 16. 10y Peer Rejection | −.18 | −.13 | .34 | .32 | .37 | .22 | −.33 | −.31 | .46 | .34 | −.52 | −.31 | −.29 | .38 | −.47 | -- | ||

| 17. Child Gender | .09 | .06 | −.08 | −.08 | −.21 | −.34 | .29 | .08 | −.30 | .17 | .34 | .08 | .05 | −.13 | .08 | −.09 | -- | |

| 18. Child Race | −.05 | −.12 | −.00 | .15 | .11 | .18 | −.11 | −.10 | .12 | −.03 | −.03 | .01 | −.18 | .09 | .03 | −.10 | .07 | -- |

| Mean | 3.40 | 3.11 | 1.72 | 1.64 | .00 | .01 | .14 | .06 | −.01 | .01 | .06 | .05 | .07 | −.08 | .08 | .04 | 1.55 | 1.40 |

| SD | .35 | .46 | .28 | .52 | .99 | .99 | .96 | .94 | .91 | .99 | .99 | .99 | .97 | .95 | .95 | .98 | .50 | .66 |

| Min | 2.25 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 | −1.34 | −1.57 | −1.91 | −1.90 | −1.02 | −1.32 | −1.80 | −1.40 | −2.10 | −2.23 | −2.26 | −1.61 | 1 | 1 |

| Max | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.07 | 3.67 | 2.99 | 3.53 | 2.61 | 2.62 | 4.06 | 4.16 | 2.52 | 3.67 | 2.31 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 3.10 | 2 | 2 |

| N | 323 | 277 | 323 | 277 | 255 | 252 | 255 | 251 | 215 | 215 | 215 | 213 | 255 | 255 | 215 | 215 | 338 | 338 |

Note: MR = Mother Report; TR = Teacher Report; Agg = Aggression. Child Gender (1 = boys, 2 = girls); Child Race (1 = Caucasian, 2 = Other). Bold coefficients are significant, p < .05.

Social behaviors.

Two dimensions each of positive and negative social behavior were measured utilizing the sociometric measurement method. School peers of study children participated in a sociometric nomination procedure (modified procedures by Terry, 2000; Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982) in second and fifth grades. A roster was used and children were asked to nominate peers on categorical behavioral descriptions. Nominations were unlimited and were not constrained to same-gender in order to improve reliability (Marks, Babcock, Cillessen, & Crick, 2013). The number of nominations children received for each description were then standardized within classrooms in second grade and schools in fifth grade, with lower scores representing fewer nominations. Standardization was based on all nominations of all participating students in the classroom, including those who are not part of the current study; therefore, although all peer nomination variables are calculated as z-scores, the means and standard deviations in Table 1 do not reflect the full range of standardized scores, only those of the focal study children. Children were encouraged to nominate at least three classmates for each description.

Representing positive social behavior, cooperation was indicated by the item, “kids who work together, help others, and share,” and leadership was indicated by the item, “kids who are leaders, the kids who others look up to.” Direct aggression was indicated by the item, “kids who start fights, say mean things, and hit other kids,” and indirect aggression was indicated by the item, “kids who make up stories about other kids that aren’t true and spread rumors.” Following common practice (i.e., Bowker, Spencer, Thomas, & Gyoerkoe, 2012; Cillessen, Jiang, West, & Laszkowski, 2005; Reavis, Keane, & Calkins, 2010) these are single-item measures. Reliability is not generally viewed as problematic with sociometric nominations due to their multi-reporter nature.

Peer status.

The same sociometric nomination procedure was utilized to assess peer rejection and acceptance. Children were asked to give unlimited nominations for the peers they “most liked” and peers they “least liked.” These nominations were standardized within classroom or grade and were used to indicate peer acceptance and peer rejection, respectively.

Analytic Plan

A structural equation modeling analysis was conducted to examine the associations among children’s emotion regulation, positive social behaviors and negative social behaviors, and peer status utilizing Mplus (Version 7; Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Model Fit for all analyses was examined using the chi-square goodness of Fit statistic, the comparative Fit indices (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI values of .90 to .95 indicate adequate Fit of the data, and values of .95 or higher indicate a good model Fit. RMSEA values below .05 indicate a good model Fit, and values ranging from .06 to .08 indicate an adequate model Fit (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Muller, 2000). Models were estimated using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to handle missing data, which results in less biased parameter estimates and appropriate standard errors compared to other missing data techniques (Schafer & Graham, 2002).

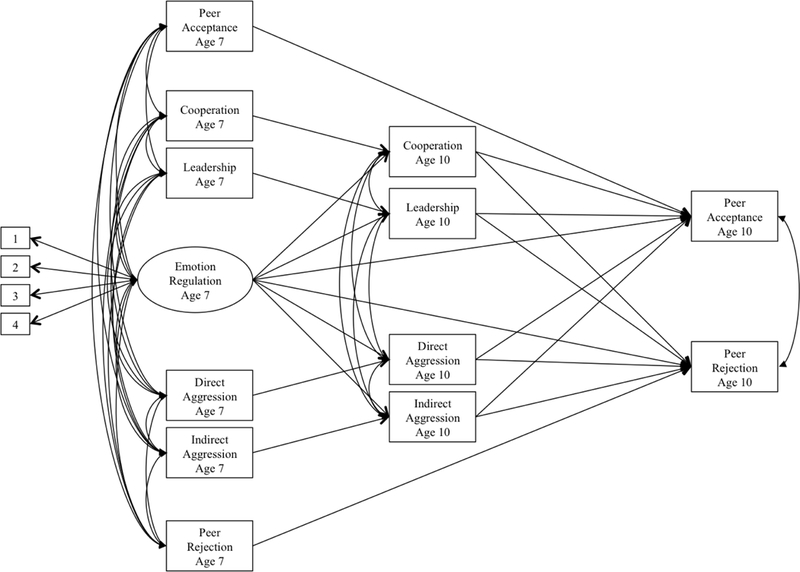

The full analytic model for the current study is pictured in Figure 1. We tested the extent to which 7-year emotion regulation predicted 10-year social behaviors, which in turn predicted 10-year peer status. We controlled for earlier levels of social behaviors in order to test the hypothesis that emotion regulation at age 7 predicts social behaviors at age 10 above and beyond social behaviors at age 7. In addition, all associations among peer-nominated variables were modeled such that cross-sectional effects at age 10 were the focus of the analysis; however, we controlled for these variables, and their associations, at age 7. Controlling for earlier levels of mediating and endogenous variables is often considered a requirement for examining longitudinal mediational models because it reduces the likelihood of inflated estimates of causal paths (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Thus, the model controls for any previous associations among these variables, allowing us to focus in on the associations at age 10 without concern for underlying effects from earlier in childhood, as well as improving internal validity (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002).

Figure 1.

Proposed analytic model examining the indirect effects of emotion regulation on peer status. Not pictured: all variables were regressed onto child gender and race.

In order to test the indirect pathways leading from 7-year emotion regulation to 10-year peer acceptance and peer rejection, we utilized a bootstrapping procedure (5,000 draws). This approach has been shown to generate the most accurate confidence intervals for indirect effects, reducing Type 1 error rates and increasing power over other similar tests (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Therefore, we utilized 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals derived from the bootstrapping procedure to evaluate the significance of the indirect effects.

All model variables were regressed onto child gender (1 = boys; 2 = girls) and race (1 = White; 2 = Other). We also considered family socioeconomic status as a potential covariate, but it was not significantly associated with any of our model variables, and therefore was not included in subsequent analyses.

Results

Preliminary Results

Means, standard deviations, minimum and maximum values, and intercorrelations for all model variables are shown in Table 1. All variables of emotion regulation and lability variables were significantly correlated, including both mother and teacher report, adding support to our use of these to create a latent variable. The means of both reports of emotion regulation were fairly high, and the means of lability were relatively low. This suggests that the sample as a whole was relatively well-regulated, though there was still considerable variability around the means.

There was considerable consistency in peer reports of children’s behaviors. All peer-nominated social behaviors at age 7 were significantly correlated (Table 1). At age 10, all peer-nominated social behaviors were correlated significantly, with the exception of leadership and direct aggression (r = −.04, p > .05), and leadership and indirect aggression (r = .06, p > .05). Additionally, all social behaviors at age 7 were significantly associated with the equivalent behaviors at age 10. Finally, all reports of peer acceptance and peer rejection, at both time points, were significantly correlated.

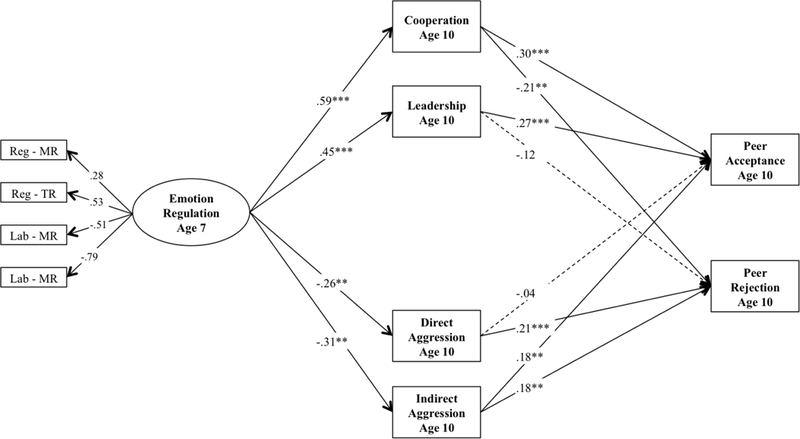

Measurement Model

The measurement model for the latent variable of emotion regulation had adequate fit, χ2 (3, N = 338) = 6.22, p = .10, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06. Indicators were all significant and in the expected directions (see Figure 2 for standardized factor loadings). In order to account for the fact that two indicators were mother reported and two were teacher reported, we allowed measurement errors within-reporter to correlate.

Figure 2.

Standardized estimates of the path analysis testing direct and indirect effects of emotion regulation on peer acceptance and peer rejection, adjusted for child gender and race, as well as all peer variables at age 7; these variables are not pictured for the sake of parsimony. In addition, all within-time correlations were modeled for ages 7 and 10. Dotted lines represent non-significant paths. Model Fit, χ2 (75, N = 338) = 133.29, p = .00, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .05. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Direct Effects

The full structural model had good fit, χ2 (73, N = 338) = 129.92, p = .00, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .05. The direct effects from emotion regulation to peer acceptance and peer rejection were not significant, so we then tested a model where these paths were constrained to zero. The model with no direct effects had good fit, χ2 (75, N = 338) = 133.29, p = .00, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .05 (Figure 2), and was not significantly different from the previous model, ∆χ2 (2, N = 338) = 3.37, p = .19, indicating that these paths did not contribute significantly to the fit of the model. Therefore, we proceeded with the model with no direct effects as our final model.

As expected, emotion regulation significantly predicted all four social behaviors. Higher levels of emotion regulation at age 7 were associated with higher levels of cooperation and leadership as well as lower levels of direct and indirect aggression at age 10, controlling for 7-year levels of these social behaviors. Also as expected, higher levels of cooperation and leadership were associated with higher levels of peer acceptance (see Figure 2 for standardized estimates), and higher levels of direct and indirect aggression were associated with higher levels of peer rejection. Leadership was not significantly associated with peer rejection, and direct aggression was not significantly associated with peer acceptance.

Indirect Effects

We then examined the indirect effects of emotion regulation on peer rejection and acceptance through cooperation and leadership. Results are displayed in Table 2. All variables that were significantly associated with the peer outcomes were also significant mechanisms through which emotion regulation shaped peer status. Specifically, emotion regulation was related indirectly to peer acceptance through cooperation, leadership, and indirect aggression. In addition, emotion regulation was indirectly related to peer rejection through direct and indirect aggression, as well as cooperation.

Table 2.

Unstandardized Estimates and 95% Bias-Corrected Bootstrap Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects

| Unstandardized Estimates | Lower C.I. | Upper C.I. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effects to Peer Rejection | |||

| Emotion regulation → Direct aggression → Peer rejection | −.05 | −.15 | −.01 |

| Emotion regulation → Indirect aggression → Peer rejection | −.05 | −.14 | −.01 |

| Emotion regulation → Cooperation → Peer rejection | −.10 | −.24 | −.01 |

| Emotion regulation → Leadership → Peer rejection | −.04 | −.12 | .01 |

| Indirect Effects to Peer Acceptance | |||

| Emotion regulation → Direct aggression → Peer acceptance | .01 | −.02 | .08 |

| Emotion regulation → Indirect aggression → Peer acceptance | −.06 | −.13 | −.02 |

| Emotion regulation → Cooperation → Peer acceptance | .19 | .09 | .41 |

| Emotion regulation → Leadership → Peer acceptance | .12 | .05 | .25 |

Discussion

Given the importance of peer relationships for positive youth development, additional information about the processes by which children gain peer acceptance or rejection is needed. This study aimed to bring together separate bodies of research that examine emotion regulation as a predictor of social behaviors and examine social behaviors as predictors of peer status. Guided by theories of socioemotional development, we tested an indirect effects process model whereby direct and indirect aggression, cooperation, and leadership were linking mechanisms between emotion regulation at age 7 and peer status at age 10. Although previous research has examined many of the individual pathways included in this study, this is the first attempt to bring them together in an integrated model that reflects a developmental process linking emotion regulation to later success or failure with peers. Overall, our results indicated emotion regulation at age 7 predicted all four social behaviors of interest at age 10: direct and indirect aggression, cooperation, and leadership. There were no direct effects from emotion regulation to either peer acceptance or peer rejection, but emotion regulation was significantly related to later peer rejection and acceptance indirectly through these social behaviors.

Negative Social Behaviors as Mechanisms

Direct aggression was a significant mechanism linking emotion regulation and peer rejection, but not peer acceptance. Indirect aggression was a significant mechanism linking emotion regulation and both peer rejection and acceptance. Children who were lower in emotion regulation at age 7 were rated as higher in direct and indirect aggression at age 10, after controlling for both types of aggression at age 7. These findings are consistent with previous literature that has demonstrated that emotion regulation is associated with multiple forms of aggression, both concurrently and longitudinally (Bowie, 2010; Sullivan et al., 2008; Crockenberg et al., 2008; Eisenberg et al., 2001). This study extends this body of literature by examining the associations in middle childhood and testing both direct and indirect aggression simultaneously. Our results indicated that children who were perceived by mothers and teachers as better regulated emotionally at age 7 were less likely to utilize either direct or indirect aggression with their peers in preadolescence. This may be because the ability to manage emotional arousal effectively allows children to utilize other strategies for managing social situations so that they do not need to rely on aggressive behaviors (Izard & Kobak, 1991).

In accord with our prediction and prior research (Salmivalli et al., 2000), children who were reported to be higher in indirect aggression were more likely to be both accepted and rejected by peers, reflecting the complex nature of indirect aggression. The motivation for engaging in indirect aggression is often to establish or maintain social power without risking negative outcomes from authority figures or other peers (Crick & Grotpeter, 1996). Thus, when used effectively, indirect aggression is likely to be associated with high peer status. On the other hand, indirect aggression also positively predicted peer rejection. Despite the seemingly contradictory nature of these findings, they fit well with previous literature. For example, Prinstein and Cillessen (2003) found that adolescents’ levels of reputational aggression, a type of indirect aggression, when used for the purposes of getting what they wanted, were associated positively with peer status. However, the association did not hold when indirect aggression was used reactively or with no purpose other than hostility. Therefore, children’s motivations for using indirect aggression may partially explain why higher levels of indirect aggression were associated with higher levels of both peer acceptance and peer rejection. When children’s motivation to use indirect aggression is to improve social status, they are more likely to attain this goal, but when their motivation is less clear or more malicious, indirect aggression may have negative repercussions and result in peer rejection. Additional research is needed to establish children’s motivations for utilizing indirect aggression as well as efficacy in achieving their social goals by utilizing this type of behavior.

Positive Social Behaviors as Mechanisms

Cooperation was a significant mechanism linking emotion regulation and both peer acceptance and peer rejection. Leadership was a significant mechanism linking emotion regulation and peer acceptance only. Consistent with previous literature, emotion regulation predicted positive social behaviors as rated by peers. Children higher in emotion regulation at age 7 were more likely to be viewed by peers as cooperative and high in leadership by age 10, after controlling for levels at age 7. Leadership and cooperation are both effortful behaviors, which means they require more than an immediate reaction to a situation. Therefore, in order for children and preadolescents to behave in sustained positive ways, they must first effectively regulate emotional arousal in a way that allows them to recognize a social goal, such as peer acceptance, and identify and implement behaviors that help them reach that goal (Eisenberg, Smith, Sadovsky, & Spinrad, 2004; Spinrad et al., 2006). This also ties in with Rose-Krasnor’s model (1997; Rose-Krasnor & Denham, 2009) in which regulatory skills are thought to be one of the precursors to enacting social behaviors that are intended to attain specific social goals.

Indirect Effects

While there is a substantial body of research indicating that children who are able to regulate emotions appropriately in a range of situations tend to be viewed more positively by peers than other children, much less is known about specific behaviors that contribute to this association. This study provides evidence that emotion regulation shapes the development of both positive and negative social behaviors in middle childhood, and that these social behaviors are involved in peers’ evaluations of children. We compared a model with direct effects from emotion regulation to peer status with a model that included only indirect effects, and found that dropping the direct paths did not significantly change the fit of the model. This comparison is a rigorous test of mediational processes (Cole & Maxwell, 2003) and provides compelling evidence for the role of social behaviors as mechanisms that help to explain the association between emotion regulation and peer status in middle childhood.

The indirect pathways found in our model have implications for interventions aimed at improving children’s social skills and peer success. Our findings provide support for the theoretical proposition that emotion regulation is a critical foundation for developing social behaviors that peers are either attracted to or repelled by, and therefore improving regulatory abilities may be a first step toward attaining greater acceptance by peers. It is likely that these indirect pathways are particularly important in middle childhood, when children are forming intimate friendships, establishing reputations, and breaking off into cliques (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987). For example, it may be that social behaviors are critical in establishing these complex social relationships and structures, and are less important later in development when these structures are more securely in place and individuals’ status is less likely to fluctuate based on specific social behaviors.

Strengths and Limitations

In addition to bringing together the bodies of literature examining behavioral outcomes of emotion regulation and behavioral predictors of peer status, this study also includes multiple social behaviors, rather than breaking them apart into separate studies or separate models. By including each of the four social behaviors in a single model, we were able to examine the associations of each behavior with emotion regulation and peer status in the presence of other social behaviors, thereby controlling for other behaviors. This method accounts for the collinearity among social behaviors and strengthens the argument that each behavior has a unique role in the association between emotion regulation and peer status (Shadish et al., 2002).

The inclusion of both peer acceptance and peer rejection is another strength of this study. These constructs, while related, are generally considered distinct rather than opposite ends of the same construct (e.g., Coie et al., 1982; Newcomb & Bukowski, 1983). Therefore, including both peer acceptance and peer rejection in the same model acknowledges that both are important to children’s peer status. This approach also allows us to examine whether positive and negative social behaviors have unique effects on both outcomes or merely one. For example, despite the fact that many studies find that direct aggression predicts both peer rejection and acceptance (i.e., Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2011), in the current study, direct aggression predicted only peer rejection. It may be that direct aggression does not substantially add to the prediction of peer acceptance after accounting for the effects of indirect aggression, cooperation, and leadership. On the other hand, the ability to cooperate emerged as a particularly positive force for children, leading to higher levels of acceptance as well as lower levels of rejection.

It should be noted that our operationalization of peer acceptance and peer rejection does not directly align with much of the empirical work examining peer acceptance and rejection using sociometric data. There are several ways to measure and calculate these variables, but the most common operationalization is to subtract the number of disliking nominations from the number of liking nominations to index peer acceptance, and multiply this number by −1 to index peer rejection. Given that this operationalization uses the same two variables to calculate both peer acceptance and peer rejection, their values are dependent upon one another and entering them into the path model simultaneously would create a high degree of multicollinearity, subsequently impeding our ability to examine unique associations. Thus, our operationalization, which involved using liking nominations to represent peer acceptance and disliking nominations for peer rejection, was the most appropriate for our analyses. However, it is important to note that one limitation to our approach is that any comparison of our results to those of other studies of peer acceptance and rejection should be made with caution due to potential differences in construct operationalization.

The current study used sociometric nominations for several variables in the model. Despite the fact that peer reports are arguably the best way to measure these constructs, it does introduce the possibility of single-method bias. However, several factors minimize this concern for the validity of our findings. The nature of sociometric nominations is such that, although it is a single method, it is an amalgamation of the nominations of many reporters. Thus, it is unlikely that characteristics of the reporters will bias the reports. In addition, peers did not rate every classmate on each of the characteristics; thus, the peers who rated a particular child as cooperative were not necessarily the same peers who rated that child as someone they liked.

Finally, the sample of this study was originally over-sampled for children who appeared to be at-risk for externalizing behaviors when they were 2 years of age. As a result, the sample may not be representative of a community sample, which may limit the generalizability of our findings.

It was our aim to test a developmental process model examining the associations among emotion regulation, positive and negative social behaviors, and peer status. This study contributes to the current literature by extending knowledge of the specific ways in which childhood emotion regulation shapes the development of later social behaviors and peer outcomes. Our findings support the hypothesis that positive and negative social behaviors serve as the mechanisms through which the ability to regulate emotion influences later peer status.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant (MH 58144) awarded to Susan D. Calkins, Susan P. Keane, and Marion O’Brien. The authors thank the parents and children who have repeatedly given their time and effort to participate in this research and are grateful to the entire RIGHT Track staff for their help collecting, entering, and coding data.

Contributor Information

Bethany L. Blair, Department of Family and Child Sciences, Florida State University

Meghan R. Gangle, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Nicole B. Perry, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Marion O’Brien, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Susan D. Calkins, Department of Psychology, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro Department of Human Development and Family Studies, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Susan P. Keane, Department of Psychology, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Lilly Shanahan, Department of Psychology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

- Achenbach TM (1992). Manual for the child behavior checklist/2–3 and 1992 profile. Burlington, VT: University of VT, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenio WF, Cooperman S, & Lover A (2000). Affective predictors of preschoolers’ aggression and peer acceptance: Direct and indirect effects. Developmental Psychology, 36, 438–448. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.4.438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, & McDonald KL (2009). The behavioral basis of acceptance, rejection, and perceived popularity In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 232–248). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ (1982). The features and effects of friendship in early adolescence. Child Development, 53, 1447–1460. doi: 10.2307/1130071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Björkqvist K, Lagerspetz KM, & Kaukiainen A (1992). Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 18, 117–127. doi: 10.1002/1098-2337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair BL, Perry NB, O’Brien M, Calkins SD, Keane SP, & Shanahan L (2014). The indirect effects of maternal emotion socialization on friendship quality in middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 50, 566–576. doi: 10.1037/a0033532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowker JC, Spencer SV, Thomas KK, & Gyoerkoe EA (2012). Having and being an other-sex crush during early adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 111, 629–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie BH (2010). Emotion regulation related to children’s future externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23, 74–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, & Furman W (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development, 58, 1101–1113. doi: 10.2307/1130550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD (2011). Biopsychosocial models and the study of family processes and child adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 817–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00847.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Gill KL, Johnson MC, & Smith CL (1999). Emotional reactivity and emotional regulation strategies as predictors of social behavior with peers during toddlerhood. Social Development, 8, 310–334. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Gill KL, Johnson MC, & Smith CL (1999). Emotional reactivity and emotional regulation strategies as predictors of social behavior with peers during toddlerhood. Social Development, 8, 310–334. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, & Hill A (2007). Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation: Biological and environmental transactions in early development In Gross JJ (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 229–248). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Stucky BD, Sawalani GM, & Little TD (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79, 1185–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiglia AC, LoCoco A, & Zappulla C (1998). Aspects of social reputation and peer relationships in Italian children: A cross-cultural perspective. Developmental Psychology, 34, 723–730. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.4.723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau D, & Nicol AM (2002). Emotional intelligence and leadership in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 33, 1101–1113. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00216-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AN, Jiang X, West TV, & Laszkowski DK (2005). Predictors of dyadic friendship quality in adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 165–172. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, & Coppotelli H (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–570. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, & Kupersmidt JB (1990). Peer group behavior and social status In Asher SR &, Coie JD (Eds.), Peer rejection in childhood (pp. 17–59). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, & Maxwell SE (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Weimer BL, Gentzler AL, & Tomich PL (2000). Emotion regulation as a mediator of associations between mother–child attachment and peer relationships in middle childhood. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 111–124. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.14.1.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Grotpeter JK (1996). Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 367–380. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400007148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM, & Jó P (2008). Predicting aggressive behavior in the third year from infant reactivity and regulation as moderated by maternal behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 37–54. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Blair KA, DeMulder E, Levitas J, Sawyer K, Auerbach-Major S, & Queenan P (2003). Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence. Child Development, 74, 238–256. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA (1983). Behavioral antecedents of peer social status. Child Development, 54, 1386–1399. doi: 10.2307/1129802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, & ... Guthrie IK (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72, 1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Bernzweig J, Karbon M, Poulin R, & Hanish L (1993). The relations of emotionality and regulation to preschoolers’ social skills and sociometric status. Child Development, 64, 1418–1438. doi: 10.2307/1131543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, & Morris AS (2002). Children’s emotion-related regulation In Kail RV (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior, Vol. 30 (pp. 189–229). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Smith CL, Sadovsky A, & Spinrad TL (2004). Effortful control: Relations with emotion regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood In Baumeister RF & Vohs KD (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 259–282). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW (1964). Friendship status and the effectiveness of peers reinforcing agents. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 1, 154–162. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(64)90017-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW, & Stevens N (1997). Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 355–370. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead ADB (1975). Four factor index of social status. Yale University, Department of Sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA (2001). Emotion expression processes in children’s peer interaction: The role of peer rejection, aggression, and gender. Child Development, 72, 1426–1438. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironsmith M, & Poteat G (1990). Behavioral correlates of preschool sociometric status and the prediction of teacher ratings of behavior in kindergarten. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19, 17–25. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1901_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, & Kobak R (1991). Emotions system functioning and emotion regulation In Garber J & Dodge KA (Eds.), The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation (pp. 303–321). New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511663963.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keane SP, & Calkins SD (2004). Predicting kindergarten peer social status from toddler and preschool problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 409–423. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000030294.11443.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerspetz KM, Björkqvist K, & Peltonen T (1988). Is indirect aggression typical of females? Gender differences in aggressiveness in 11- to 12-year-old children. Aggressive Behavior, 14, 403–414. doi: 10.1002/1098-2337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, & Williams J (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks PE, Babcock B, Cillessen AH, & Crick NR (2013). The effects of participation rate on the internal reliability of peer nomination measures. Social Development, 22, 609–622 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00661.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Mennin DS, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2011). Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: A prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 544–554. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostow AJ, Izard CE, Fine S, & Trentacosta CJ (2002). Modeling emotional, cognitive, and behavioral predictors of peer acceptance. Child Development, 73, 1775–1787. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, & Bukowski WM (1983). Social impact and social preference as determinants of children’s peer group status. Developmental Psychology, 19, 856–867. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.19.6.856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, & Cillessen AN (2003). Forms and functions of adolescent peer aggression associated with high levels of peer status. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 310–342. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2003.0015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Rancourt D, Guerry JD, & Browne CB (2009). Peer reputations and psychological adjustment In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 548–567). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramani GB, Brownell CA, & Campbell SB (2010). Positive and negative peer interaction in 3- and 4-year-olds in relation to regulation and dysregulation. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 171, 218–250. doi: 10.1080/00221320903300353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavis RD, Keane SP, & Calkins SD (2010). Trajectories of peer victimization: The role of multiple relationships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56, 303–332. doi: 10.1353/mpq.0.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodkin PC, Ryan AM, Jamison R, & Wilson T (2013). Social goals, social behavior, and social status in middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 49, 1139–1150. doi: 10.1037/a0029389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röll J, Koglin U, & Petermann F (2012). Emotion regulation and childhood aggression: Longitudinal associations. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 43, 909–923. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0303-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Krasnor L (1997). The nature of social competence: A theoretical review. Social Development, 6, 111–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.1997.tb00097.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Krasnor L, & Denham S (2009). Social-emotional competence in early childhood In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 162–179). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C (1999). The development of emotional competence. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli C, Kaukiainen A, & Lagerspetz K (2000). Aggression and sociometric status among peers: Do gender and type of aggression matter? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 41, 17–24. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A (2010). Dynamic developmental systems: Chaos and order In Evans GW & Wachs TD (Eds.), Chaos and its influence on children’s development: An ecological perspective (pp. 255–264). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/12057-016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, & Graham JW (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, & Müller H (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of psychological research online, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish W, Cook T, and Campbell D (2002). Experimental and quasi experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, & Cicchetti D (1997). Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology, 33, 906–916. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Ryan RM, & Cicchetti D (2001). Narrative representations of caregivers and emotion dysregulation as predictors of maltreated children’s rejection by peers. Developmental Psychology, 37, 321–337. doi.org/10.1037/0012–1649.37.3.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin N, Vaughn BE, Akers V, Kim M, Stevens S, Krzysik L, ... & Korth B (2011). Are happy children socially successful? Testing a central premise of positive psychology in a sample of preschool children. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 355–367. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2011.584549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M (2001). Social and emotional competencies: Contributions to young African-American children’s peer acceptance. Early Education and Development, 12, 49–72. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1201_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Fabes RA, Valiente C, Shepard SA, ... & Guthrie IK (2006). Relation of emotion-related regulation to children’s social competence: a longitudinal study. Emotion, 6, 498–510. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Helms SW, Kliewer W, & Goodman KL (2010). Associations between sadness and anger regulation coping, emotional expression, and physical and relational aggression among urban adolescents. Social Development, 19, 30–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00531.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry R (2000). Recent advances in measurement theory and the use of sociometric techniques In Cillessen AN & Bukowski WM (Eds.), Recent advances in the measurement of acceptance and rejection in the peer system (pp. 27–53). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, & Izard CE (2007). Kindergarten children’s emotion competence as a predictor of their academic competence in first grade. Emotion, 7, 77–88. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, & Shaw DS (2009). Emotional self-regulation, peer rejection, and antisocial behavior: Developmental associations from early childhood to early adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30, 356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller M, Vannatta K, Schafer J, & Noll RB (2003). Behavioral reputation: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 39, 129–139. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]