The objective of this study was to identify histopathologic parameters with prognostic significance to distinguish early gastric cancers with different clinical behavior and to facilitate the planning of multidisciplinary therapy tailored to early gastric cancer.

Keywords: Early gastric cancer, Definition, Prognosis, Treatment

Abstract

Background.

Early gastric cancer (EGC) generally has a good prognosis. However, the current definition of EGC includes various subgroups of patients with different pathological characteristics and different prognoses, some of whom have aggressive disease with a biological behavior similar to that of advanced carcinoma.

Materials and Methods.

We retrospectively evaluated 1,074 patients with EGC who had undergone surgery between 1982 and 2009. The cumulative incidence function of cancer‐specific mortality and competing mortality were estimated using the Fine and Gray method.

Results.

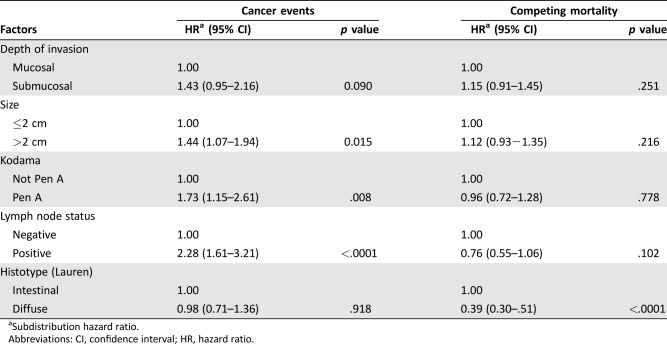

The median follow‐up period was 193 months (range 1–324). Five hundred and sixty‐two (52.3%) patients died, 96 (8.9%) from EGC. The 5‐, 10‐, and 15‐year cumulative incidence rates for mortality of all causes were 20.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 18.0–22.9), 37.1% (95% CI 34.7–40.7), and 52.6% (95% CI 49.1–56.0), respectively; for cancer‐specific mortality, 6.0% (95% CI 4.5–7.6), 9.9% (95% CI 7.9–11.9), and 11.1% (95% CI 8.8–13.3), respectively; and for mortality of other causes, 14.4% (95% CI 12.1–16.6), 27.2% (95% CI 24.2–30.2), and 41.5% (95% CI 38.1–43.3), respectively. A significant increase in the risk of cancer‐specific mortality was observed for lesions >2 cm (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] = 1.44, 95% CI 1.07–1.94), Pen A‐type disease (adjusted HR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.15–2.61), and node‐positive cancers (adjusted HR = 2.28, 95% CI 1.61–3.21).

Conclusion.

Patients with EGC with tumors >2 cm, Pen A‐type disease according to Kodama, or lymph node metastases show a poorer prognosis and an increased risk of cancer‐specific mortality.

Implications for Practice.

Early gastric cancer generally has a good prognosis, and some patients can be treated radically by endoscopic resection. However, the current definition of early gastric cancer includes subgroups of patients with an aggressive disease. In particular, patients with lymph node metastases and Pen A‐type tumors according to Kodama's classification need a more invasive treatment, such as subtotal or total gastrectomy with an extended D2 lymphadenectomy, plus eventual adjuvant chemotherapy.

摘要

背景.早期胃癌(EGC)通常具有良好的预后。然而,当前的EGC定义包括具有不同病理特征和不同预后的多个患者亚组,其中一些侵袭性疾病的生物学行为与晚期肿瘤相似。

材料与方法.我们对曾在1982年至2009年之间进行过手术的1 074例EGC患者进行回顾性评价。使用Fine和Gray方法估算癌症特异性死亡率和竞争性死亡率的累积发生率函数。

结果.中位随访期为193个月(范围1‐324)。562例(52.3%)患者死亡,96例(8.9%)死于EGC。全因死亡率的5、10和15年累积发生率分别为20.5%[95% 置信区间(CI)18.0‐22.9]、37.1%(95% CI 34.7‐40.7)和52.6%(95% CI 49.1‐56.0);癌症特异性死亡率,分别为6.0%(95% CI 4.5‐7.6)、9.9%(95% CI 7.9‐11.9)和11.1%(95% CI 8.8‐13.3);其他原因导致的死亡率,分别为14.4%(95% CI 12.1‐16.6)、27.2%(95% CI 24.2‐30.2)和41.5%(95% CI 38.1‐43.3)。在病灶>2cm[校正风险比(HR)=1.44,95% CI 1.07‐1.94]、存在Pen A型疾病(校正HR=1.73,95% CI 1.15‐2.61)和淋巴结阳性(校正HR=2.28,95% CI 1.61‐3.21)的情况下,观察到癌症特异性死亡率的风险显著增加。

结论.肿瘤>2cm、存在Pen A型疾病(根据Kodama)或淋巴结转移的EGC患者显示预后更差且癌症特异性死亡风险增加。

对临床实践的提示:早期胃癌通常具有良好的预后,一些患者可通过内镜切除得到根治。然而,当前的早期胃癌定义包括存在侵袭性疾病的患者亚组。尤其是存在淋巴结转移和Pen A型肿瘤(根据Kodama分类)的患者需要更积极的治疗,如胃大部切除术或全胃切除术和广泛性D2淋巴结切除术,可能联合辅助化疗。

Introduction

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined as a tumor limited to the mucosa and/or submucosa regardless of lymph node status [1] and is generally considered to have good prognosis. However, many authors have reported the risk of nodal metastases and treatment failure for EGC [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. The widespread use of endoscopic treatment since the introduction of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has enabled a certain number of EGCs with well‐defined pathological characteristics to be radically treated in skilled centers [7], [8]. The most recent Japanese Gastric Cancer Association treatment guidelines [9] defined the standard criteria on the basis of which ESD can be considered curative.

The incidence of gastric cancer in Italy varies from one region to another but is notably higher in Emilia‐Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria, and Marche. Nonetheless, the incidence in these areas is significantly lower than that of Eastern countries. In Romagna, in particular, the catchment area of Forlì, a substantial increase in the number of gastric cancers diagnosed at an early stage (36% of all first diagnoses of gastric cancer) has been observed in recent years since the implementation of sporadic population screening. This is an excellent result for Western countries but not comparable with the percentage of EGCs detected in Eastern countries, where organized population screening program is active [10], [11]. In our previous study conducted on 530 patients with EGC, univariate analysis showed that Kodama's type, lymph node status in terms of both number and pathological stage according to the tumor, nodes and matastases (TNM) Classification of Malignant Tumors, 7th edition, and depth of infiltration were significant prognostic factors [12]. Multivariate analysis identified Kodama's Pen A type and lymph node status, especially when more than three positive nodes were present, as the only independent prognostic factors, suggesting that the inclusion of these parameters could serve to improve the definition and classification of EGC. We thus took into account our previous data when designing the present study and made our primary aim that of identifying histopathologic parameters with prognostic significance to distinguish between EGCs with different clinical behavior and facilitate the planning of multidisciplinary therapy tailored to EGC type.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed data from 1,074 patients aged ≥18 years who underwent surgery for EGC between 1982 and 2009 in seven Italian centers (Forlì, Varese, Siena, Verona, Milan, Rome, and Perugia), all of which are members of the Italian Gastric Cancer Research Group (GIRCG). In accordance with GIRCG guidelines, the study centers use common diagnostic and surgical criteria and procedures [13]. Variables in the analysis included age at diagnosis, gender, depth of infiltration, tumor size, histologic, macroscopic and Kodama's types, lymph node status according to the TNM 7th Edition, and tumor site. All patients underwent subtotal or total gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy, as per the Japanese guidelines. Paris [14], Lauren [15] and Kodama [16] criteria were used, respectively, to classify tumors macroscopically, microscopically, and according to their growth pattern. A pathologist from each center with expertise in gastrointestinal diseases and long‐standing collaborations with multidisciplinary dedicated groups reviewed the cases to accurately reclassify the tumors according to the aforementioned classifications. Population‐based cancer registries provided information on deaths, that is, date of death and underlying cause of death obtained from the death certificate, coded using the International Classification of Diseases, versions 9 and 10. The study was approved by the Local Ethical Committee. Written informed consent was not necessary because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint of this study was the risk of gastric cancer‐specific mortality.

The Mantel‐Haenszel chi‐square test was used to compare the distribution of lymph node metastases and depth of infiltration, tumor size, and Kodama and histologic types. Overall survival was defined as the time from surgical treatment to death from any cause. Causes of death were classified as gastric cancer‐specific mortality and other‐cause mortality (i.e., competing mortality). Surviving patients were censored at their last date of follow‐up.

The cumulative probability of gastric cancer mortality and competing causes of death were calculating using nonparametric cumulative incidence functions [17]. The cumulative incidence function (i.e., the predicted cumulative risk of death) adjusted for competing risks by calculating the cumulative probability of dying from gastric cancer at each time point.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for gastric cancer‐specific mortality and for other‐cause mortality with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values were calculated for each covariate using the Fine and Gray regression model.

Schoenfeld residuals were computed, and residuals were plotted against time in years [18]. A nonzero slope of Schoenfeld residuals against time indicates a violation of the proportional hazard assumption, which we did not observe. Thus, no evidence was found against proportional hazards assumptions.

STATA version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) were used for the statistical analyses.

Results

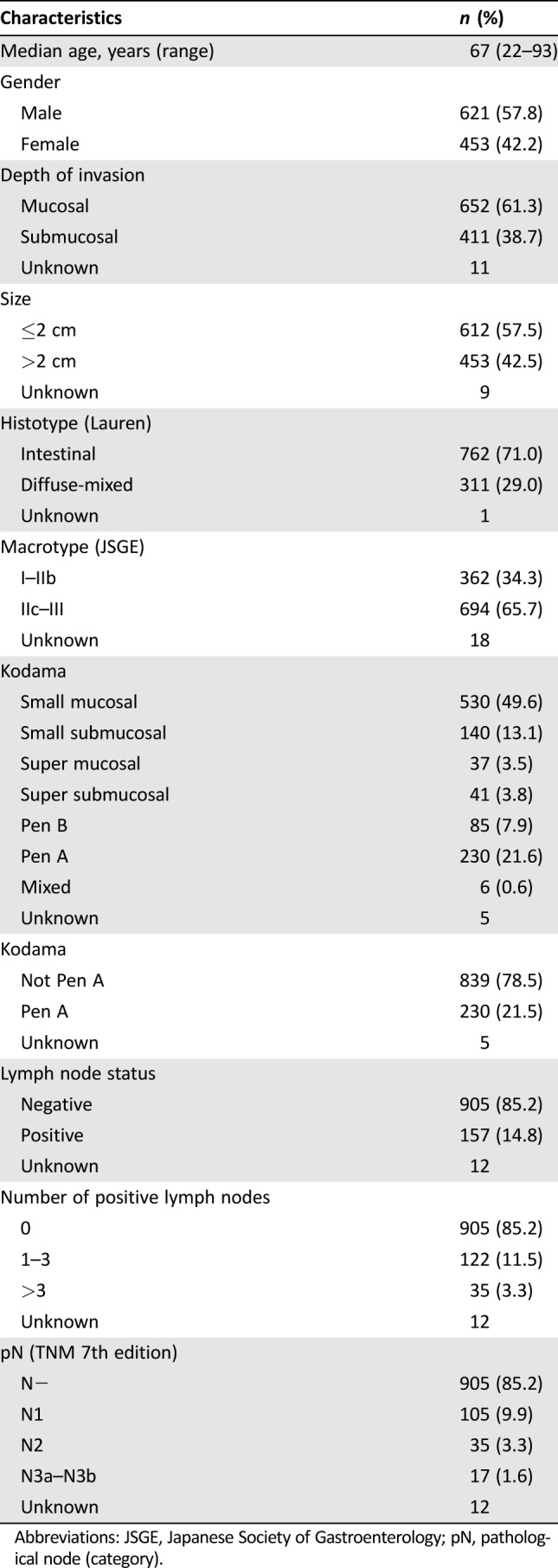

Of the 1,074 patients taking part in the study, 621 (57.8%) were men and 453 (42.2%) were women. The median age was 67 years (range 22–93). About 66% of EGCs were located in the lower third of the stomach. Full patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. One hundred and fifty‐seven (14.8%) patients had lymph node metastases.

Table 1. Patient and tumor characteristics (n = 1,074).

Abbreviations: JSGE, Japanese Society of Gastroenterology; pN, pathological node (category).

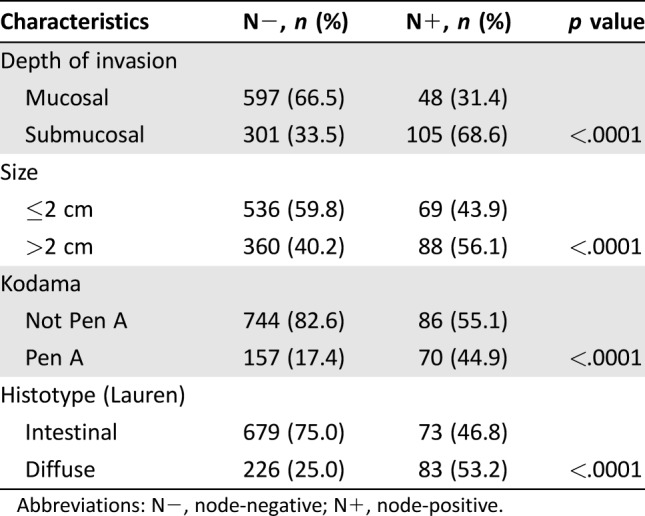

Lymph node involvement was significantly higher in histological diffuse types (p < .0001), submucosal tumors (p < .0001), tumors >2 cm (p < .0001), and Pen A‐type lesions (p < .0001; Table 2). The overall number of deaths was 562 (52.3%), of which 466 (43.4%) were from other causes and 96 (8.9%) were gastric cancer‐related.

Table 2. Distribution of lymph node metastases.

Abbreviations: N−, node‐negative; N+, node‐positive.

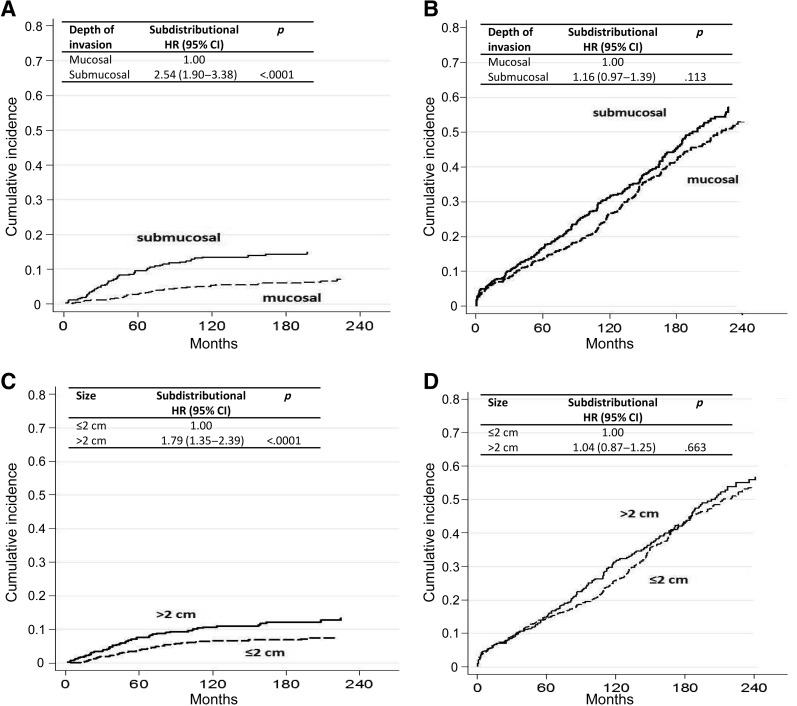

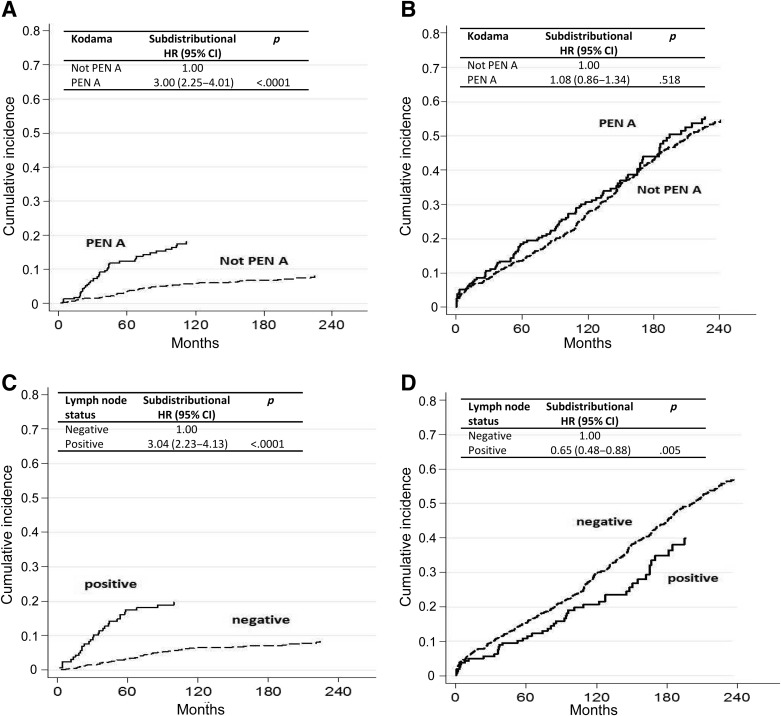

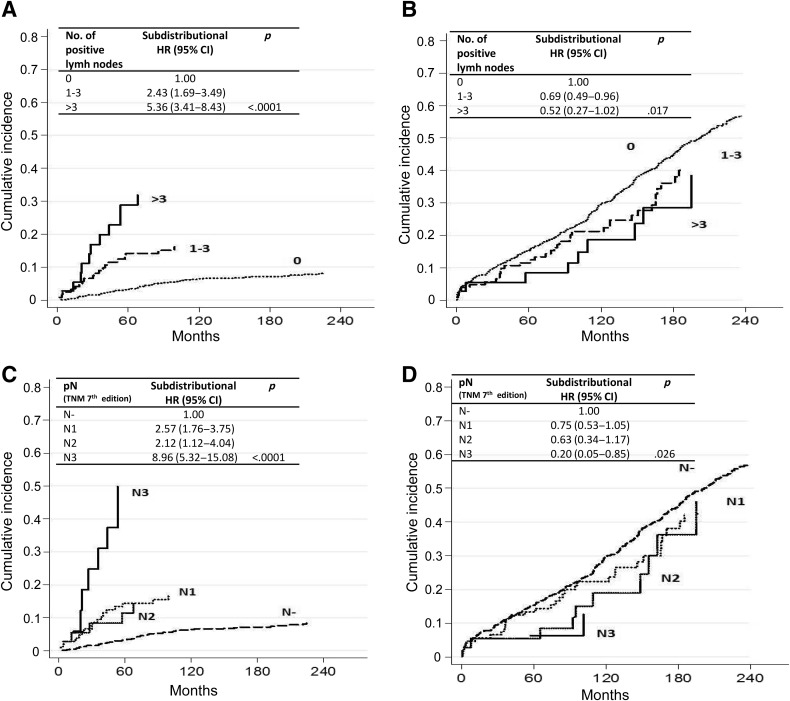

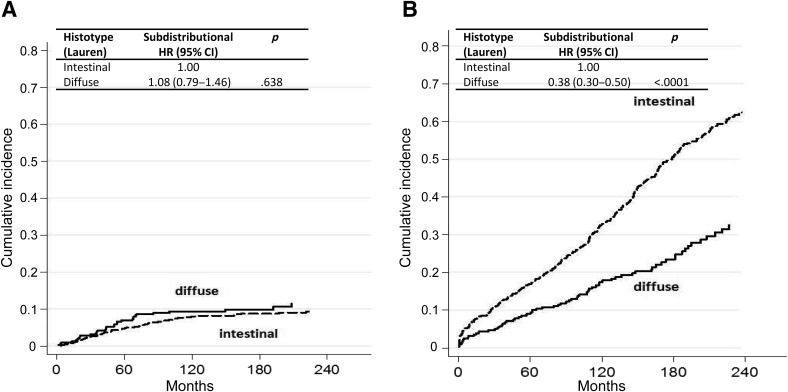

Median follow‐up was 193 months (range 1–324). The 5‐, 10‐, and 15‐year cumulative incidence rates for mortality of all causes were 20.5% (95% CI 18.0–22.9), 37.1% (95% CI 34.7–40.7) and 52.6% (95% CI 49.1–56.0), respectively; for cancer‐specific mortality, 6.0% (95% CI 4.5–7.6), 9.9% (95% CI 7.9–11.9), and 11.1% (95% CI 8.8–13.3), respectively; and for other‐cause mortality, 14.4% (95% CI 12.1–16.6), 27.2% (95% CI 24.2–30.2) and 41.5% (95% CI 38.1–43.3), respectively. In univariate competing‐risks regression analysis, a significant increase in the risk of gastric cancer‐related mortality was observed in patients with submucosal tumors, lesions >2 cm, Pen A‐type disease, and node‐positive cancers (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4). Moreover, node‐positive cancer and diffuse histologic type were associated with a significantly decreased risk of other‐cause mortality.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence for (A) gastric cancer‐specific mortality by depth of invasion after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to other causes), (B) other‐cause mortality by depth of invasion after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to gastric cancer), (C) gastric cancer‐specific mortality by size after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to other causes), and D) other‐cause mortality by size after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to gastric cancer).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence for (A) gastric cancer‐specific mortality by Kodama type (Pen A or not Pen A) after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to other causes), (B) other‐cause mortality by Kodama type (Pen A or not Pen A) after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to gastric cancer), (C) gastric cancer‐specific mortality by lymph node status after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to other causes), and (D) other‐cause mortality by lymph node status after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to gastric cancer).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence for (A) gastric cancer‐specific mortality by number of positive lymph nodes after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to other causes), (B) other‐cause mortality by number of positive lymph nodes after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to gastric cancer), (C) gastric cancer‐specific mortality by pN (TNM 7th Edition) after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to other causes), and (D) other‐cause mortality by pN (TNM 7th Edition) after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to gastric cancer).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; pN, .

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence for (A) gastric cancer‐specific mortality by histotype after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to other causes) and (B) other‐cause mortality by histotype after adjusting for competing risk (i.e., death due to gastric cancer).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Cause‐specific cumulative hazards of gastric cancer mortality and other‐cause mortality for different categories of tumor characteristics are shown in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4. When coefficient estimates were adjusted using the multivariable model, an association was found between gastric cancer‐related mortality and EGCs >2 cm (HR = 1.44, 95% CI 1.07–1.94), Pen A type (HR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.15–2.61), and lymph node metastases (HR = 2.28, 95% CI 1.61–3.21; Table 3). Moreover, only diffuse histological type was associated with decreased competing mortality. A significantly worse prognosis was not observed for patients with non‐Pen A‐type tumors (data not shown).

Table 3. Multivariable analysis of factors associated with gastric cancer‐related mortality.

Subdistribution hazard ratio.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

Early gastric cancer is a malignant tumor in an initial phase that generally has a good prognosis. Our results on a large patient series confirm this, with 5‐, 10‐, and 15‐year cumulative incidence rates of cancer‐specific mortality of 6.0% (95% CI 4.5–7.6), 9.9% (95% CI 7.9–11.9), and 11.1% (95% CI 8.8–13.3), respectively. However, as demonstrated by other authors [4], [5], [6], [12], [19], EGC also represents a group of tumors in an extremely heterogeneous phase of neoplastic growth, as it includes lesions with aggressive clinical behavior, often characterized by the presence of lymph node metastases. It is therefore important to identify EGCs with pathologic characteristics favoring metastatic diffusion to guarantee the most adequate treatment for patients. Our findings suggest that Kodama's Pen A and histologically diffuse types, submucosal tumors, and lesions >2 cm are all conditions that lead to a significantly higher risk of lymph node metastases. Moreover, univariate analysis revealed that patients with submucosal tumors, lesions >2 cm, Pen A type, and lymph node metastases had a substantially greater risk of dying from gastric cancer. Finally, multivariate analysis indicated size >2 cm, Pen A type, and lymph node metastases as independent prognostic factors. The analysis of 5‐, 10‐, and 15‐year survival rates of all Kodama types found that patients with Pen A tumors had a significantly worse prognosis, whereas those with cancers showing minimal submucosal infiltration had a good prognosis and manifested the biologic and clinical characteristics typical of EGCs.

It is clear that accurate pathologic staging of the disease is needed to distinguish between tumors with a good prognosis that can be completely eradicated by ESD and those with a high risk of lymph node metastases, for which surgery is mandatory. Our results demonstrate that the current definition of EGC, that is, a tumor limited to mucosa and/or submucosa regardless of lymph node status [1], is no longer appropriate because of the diverse clinical behavior and different treatment options for the disease. We propose an amended definition that considers only tumors showing mucosal and minimal submucosal infiltration according to Kodama's criteria and without lymph node metastases to be early gastric cancers [12]. We feel that this new definition of EGC allows for a better staging of the disease in ESD specimens, identifying the criteria that influence the evaluation of the radicality of the lesion by endoscopy. To this end, GIRCG guidelines [13] recommend using the standard Japanese criteria [9], a strategy supported by the results from the present study. According to GIRCG guidelines, well‐differentiated, intestinal‐type, intramucosal EGCs, <2 cm and without lymphovascular invasion, neoplastic ulceration, or margin involvement, are suitable for endoscopic treatment with curative intent. Conversely, our data would not appear to support the use of extended criteria suggested by some Japanese authors [20], [21]. Other authors maintain that wall infiltration is not as important as lymph node status for identifying the clinical behavior of EGCs [22], [23]. However, our findings further confirm the important role of deeper submucosal infiltration because of its direct implication in the development of lymph node metastases.

Cancer‐related mortality is not so different between the East and the West, but the number of EGCs is significantly higher in Japan because of the existence of organized population screening. This fact has allowed Japanese endoscopists to attain great skill in ESD of EGCs, suggesting to them also to adopt the expanded criteria for the treatment of these tumors.

As far as we know, our population of patients with EGC, recruited in specialized Italian centers, is the largest studied in Western countries to date. All the centers are members of the Italian Gastric Cancer Research Group and share standardized diagnostic and treatment procedures, aspects that enhance the value of our results.

In this study we observed 562 overall deaths (466 for other causes and 96 gastric cancer related). Thus, with at least 15 events for each variable included in the multivariable model, the number of events permitted us to construct a statistically reliable model.

However, the study is limited by the fact that our population‐based cancer registries did not record detailed data on comorbidities or other potentially relevant variables, which thus could not be included in our model. Such information would be useful to refine our competing risk model.

Conclusion

Tumors with massive submucosal infiltration, size >2 cm, or lymph node metastases should no longer be considered EGCs and require subtotal or total gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Luca Saragoni

Provision of study material or patients: Luca Saragoni, Alessandra Ravaioli, Paolo Morgagni, Franco Roviello, Carla Vindigni, Stefano Rausei, Anna Maria Chiaravalli, Uberto Fumagalli, Paola Spaggiari, Fausto Rosa, Riccardo Ricci, Annibale Donini, Paolo Giovenali, Anna Tomezzoli, Giovanni De Manzoni

Collection and/or assembly of data: Luca Saragoni, Alessandra Ravaioli, Paolo Morgagni, Franco Roviello, Carla Vindigni, Stefano Rausei, Anna Maria Chiaravalli, Uberto Fumagalli, Paola Spaggiari, Fausto Rosa, Riccardo Ricci, Annibale Donini, Paolo Giovenali, Anna Tomezzoli, Giovanni De Manzoni

Data analysis and interpretation: Luca Saragoni, Emanuela Scarpi

Manuscript writing: Luca Saragoni, Emanuela Scarpi, Alessandra Ravaioli, Paolo Morgagni, Franco Roviello, Carla Vindigni, Stefano Rausei, Anna Maria Chiaravalli, Uberto Fumagalli, Paola Spaggiari, Fausto Rosa, Riccardo Ricci, Annibale Donini, Paolo Giovenali, Anna Tomezzoli, Giovanni De Manzoni

Final approval of manuscript: Luca Saragoni, Emanuela Scarpi, Alessandra Ravaioli, Paolo Morgagni, Franco Roviello, Carla Vindigni, Stefano Rausei, Anna Maria Chiaravalli, Uberto Fumagalli, Paola Spaggiari, Fausto Rosa, Riccardo Ricci, Annibale Donini, Paolo Giovenali, Anna Tomezzoli, Giovanni De Manzoni; members of the Italian Gastric Cancer Research Group (GIRCG)

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1. Murakami T. Pathomorphological diagnosis, definition and gross classification of early gastric cancer. Gann Monogr Cancer Res 1971;11:53–66. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abe S, Yoshimura H, Nagaoka S et al. Long‐term results of operation for carcinoma of the stomach in T1/T2 stages: Critical evaluation of the concept of early carcinoma of the stomach. J Am Coll Surg 1995;181:389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sano T, Kobori O, Muto T. Lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: Endoscopic resection of tumour. Br J Surg 1992;79:241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Folli S, Dente M, Dell'Amore D et al. Early gastric cancer: Prognostic factors in 223 patients. Br J Surg 1995;82:952–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saragoni L, Gaudio M, Vio A et al. Early gastric cancer in the province of Forlì: Follow‐up of 337 patients in a high risk region for gastric cancer. Oncol Rep 1998;5:945–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saragoni L, Gaudio M, Morgagni P et al. The role of growth patterns, according to Kodama's classification, and lymph node status, as important prognostic factors in early gastric cancer: Analysis of 412 cases. Gastric Cancer 2000;3:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yada T, Yokoi C, Uemura N. The current state of diagnosis and treatment of early gastric cancer. Diagn Thor Endosc 2013;241320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gotoda T, Ho KY, Soetikno R et al. Gastric ESD: Current status and future directions of devices and training. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2014;24:213–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association . Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer 2011;14:101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer . Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. First English edition. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co, Ltd; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sano T, Sasako M, Kinoshita T et al. Recurrence of early gastric cancer. Follow‐up of 1475 patients and review of the Japanese literature. Cancer 1993;72:3174–3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saragoni L, Morgagni P, Gardini A et al. Early gastric cancer: Diagnosis, staging, and clinical impact. Evaluation of 530 patients. New elements for an updated definition and classification. Gastric Cancer 2013;16:549–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. De Manzoni G, Marrelli D, Baiocchi GL et al. The Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (GIRCG) guidelines for gastric cancer staging and treatment: 2015. Gastric Cancer 2017;20:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: Esophagus, stomach and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58(suppl 6):S3–S43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: Diffuse and so‐called intestinal‐type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo‐clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1965;64:31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kodama Y, Inokuchi K, Soejima K et al. Growth patterns and prognosis in early gastric cancer. Superficially spreading and penetrating growth types. Cancer 1983;51:320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Korn EL, Dorey FJ. Applications of crude incidence curves. Stat Med 1992;11:813–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Folli S, Morgagni P, Roviello F et al. Risk factors for lymph node metastases and their prognostic significance in early gastric cancer (EGC) for the Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (IRGGC). Jpn J Clin Oncol 2001;31:495–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirasawa T, Gotoda T, Miyata S et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated‐type early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2009;12:148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: Estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer 2000;3:219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Inoue K, Tobe T, Kan N et al. Problems in the definition and treatment of early gastric cancer. Br J Surg 1991;78:818–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koufuji K, Takeda J, Toyonaga A et al. Early gastric cancer and lymph node metastasis. Kurume Med J 1997;44:157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]