Abstract

Background:

The role of Immune system in the pathophysiology of depressive disorders is a field of active research, however Indian literature is sparse. The present study was planned to assess the immunological response in depression.

Materials and Methods:

The study comprised of 100 subjects. There were fifty cases of depression satisfying the ICD-10 criteria with no physical illness and HIV negative status and fifty age and sex matched healthy volunteers. Depression was assessed on HRSD and BDI scales. Assessment of three markers each of cellular immunity (NK cells, CD4, CD8 cells) and humoral immunity (Il-2, IL-6 and CRP) was carried out on both groups and depressed patients were reassessed on all parameters after 08 weeks of treatment with antidepressants (SSRIs or TCAs).

Results:

NK Cells were significantly higher in the depressed group and CD 8 Cells and CD 4 Cells were higher in the control group (P = 0.001). Depressed group before treatment v/s control group differed significantly in the cell mediated immune markers. IL-2 levels were higher in the control group. The markers of cell mediated immunity i.e., NK cells, CD4, CD8 had increased significantly after treatment (P =< 0.001). The humoral immunity markers (CRP and IL-2) decreased significantly after treatment (P =< 0.001). However IL -6 levels were raised significantly in the subjects after treatment (P =< 0.001).

Conclusion:

Dysregulation of immune response occurs in depressed patients with changes in both cell mediated and humoral immunity. Further, antidepressant treatment affects the immune status of depressed patients.

Keywords: Antidepressant treatment, depression, immunological response

Depression is a major health problem worldwide with a lifetime prevalence of almost 17% and annual incidence of 1.59%.[1] By 2020, it is projected that depression is going to be the second leading cause of worldwide disability. In 1980s, interest in the association between depression and the immune system arose when chronic inflammatory illnesses, for example, rheumatoid arthritis were noted to be accompanied by depression. Studies showed that cytokines modulate brain neurotransmission and the activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, both of which are disturbed in depression[2,3,4]

This line of research resulted in the propagation of “cytokine hypothesis of depression” which implies that pro-inflammatory cytokines, acting as neuromodulators, cause many of behavioral, neuroendocrine, and neurochemical changes seen in depressive disorders.[2] Meta-analysis of studies in this field suggest that depression seems to be associated with inflammation and that many immunological changes occur in patients with major depressive disorder.[5,6]

Patients with major depression have been found to exhibit significant elevations of innate immune cytokines, acute phase proteins and inflammatory mediators. Studies indicate that of these markers of inflammation, elevations in interleukin-6 (IL-6), and C-reactive protein (CRP) are among the most frequently observed.[7] Due to the relationship between body mass index and CRP and IL-6 (adipocytes are capable of producing IL-6 and so are macrophages within fatty tissues), elevations of these markers in patients with obesity should be interpreted with caution.[8,9]

It has been postulated that antidepressants which are effective in treating depression do so by acting on neurotransmitter receptors.[10] Research evidence has suggested that antidepressants of several classes decrease the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF α) and increase that of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine.[11] Thus, it has been proposed that antidepressants produce some of their effects by immunomodulation and cause reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increase of anti-inflammatory cytokines.[11]

Studies of both cell-mediated and humoral immunity markers in depression have produced conflicting results about the association between depression and immunity, although majority of the literature suggests an association between increased pro-inflammatory cytokines and depression.[10,11,12] Age also has an influence on cellular immunity, and it appears that depression exacerbates age-related immune alterations leading to decline in immunity.[13] Depressed patients show an exaggerated activation of the inflammatory response following acute psychological stress, with greater increases of IL-6 as well as activation of nuclear factor-kappa B, a transcription factor that signals the inflammatory cascade.[14] Increase in circulating levels of other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF α and IL-1 have also been reported in depressed patients.[15] Depression appears to yield increase in inflammatory markers in some patients and decreases natural killer (NK) cell response in other patients.[13]

However, most of these studies did not assess the effect of antidepressant treatment on immune markers. A review of published literature reveals that no Indian study has been undertaken in this field so far. It was therefore proposed to study the association of depression and certain markers of both cell-mediated and humoral immunity in Indian patients and also to study the effect of antidepressant treatment on this association.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample for the study comprised 100 participants. The study group comprised 50 cases of depression treated as inpatients or on outpatient department basis in the Psychiatry Department of a tertiary care hospital in Pune, and 50 age- and sex-matched participants served as the control group. The inclusion criteria for cases in the study group were those meeting International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition criteria[16] for Depressive episode, Recurrent Depressive disorder or Dysthymia, nonsmokers, nonalcoholics/abstinent from alcohol for the last 6 months and not having taken antidepressant medication for 6 months before the study. Exclusion criteria were history of any other comorbid psychiatric illness, HIV seropositivity, immunocompromised status, pregnancy, acute or chronic infections, autoimmune, allergic, neoplastic, or endocrine diseases and other acute physical diseases, including surgery or infarction of the heart or brain within the last 3 months. These illnesses were excluded by clinical interview, physical examination, and comprehensive laboratory workup focusing on parameters indicative of inflammation. Age- and sex-matched healthy volunteers with no lifetime or current diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder served as controls and underwent the same diagnostic procedures as the depressed patients to rule out any of the abovementioned exclusion criteria.

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Institute. Written informed consent was taken from all the patients and the controls. All the patients were interviewed by experienced psychiatrists. In the depressed patients, the psychopathology was quantified by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD); 17-item version[17] and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).[18] Controls who met the inclusion criteria were also interviewed to exclude any psychiatric illness and were also administered the BDI and HRSD.

Immunological parameters in the depressed patients were assessed before treatment and at the end of 8 weeks of antidepressant medication. The HRSD and BDI scores were also assessed after 8 weeks of antidepressant medication. Immunological parameters of the controls were also assessed for comparison with the depressed patients before treatment.

Peripheral blood (6 and 4 ml) was collected from each participant into vacutainers by venipuncture between 0900 h and 1200 h. The blood in the 6 ml vacutainer was used to assess the cell-mediated immunity status by measuring the NK cells, CD4, and CD8 cells on the same day of collection of blood sample using flow cytometry method. The flow cytometry machine used was BD FACS Calibur four-color flow cytometry (manufactured by BD Biosciences Becton, Dickinson and Company, 2350 Qume drive, San Jose, CA, USA 95131-1807). Serum was obtained from the blood of the 4 ml vacutainer by centrifuging at 1000 X g for 10 min and then storing the serum at −70°C. To prevent wastage of ELISA kits, serum samples were stored till 30 frozen samples were available and then these were thawed at room temperature and later quantitative determination of the humoral immunity status was carried out by measuring IL-2, IL-6, and CRP levels by enzyme immunoassay method with ELISA kits (manufactured by DIACLONE, 1, Bd A Fleming, BP 1985, 25020 Besancon Cedex, France).

The depressed patients were prescribed either serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants by treating psychiatrist. Benzodiazepines (lorazepam/clonazepam/alprazolam) were prescribed in some patients for short duration as required.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed with SPSS statistical software. Descriptives were quoted as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). BDI and HRSD scores were quoted as median scores. Comparison of immune parameters between the depressed patients and controls was done with “unpaired t-test.” Comparison of immune parameters of depressed patients before and after treatment was done using the “paired t-test.” Comparison of BDI and HRSD score in depressed patients before and after treatment was done using the Mann–Whitney U-test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

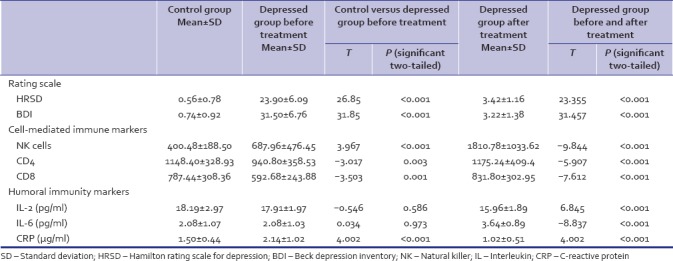

The study group consisted of 50 participants, 33 males and 17 females; mean age was 37.22 (SD-12.21) and body mass index (BMI) was 23.33 (SD-3.07). Control group had 33 males and 17 females; mean age was 38.33 (SD-10.95) and BMI was 23.70 (SD-2.61). There was no statistically significant difference in age (P = 0.68) or BMI (P = 0.512) between the two groups. The mean HRSD and BDI scores were significantly higher in the depressed group as compared to the control group as determined by the Mann–Whitney U-test (P ≤ 0.001) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Depression and immunological parameters (depressed group before treatment and control group)

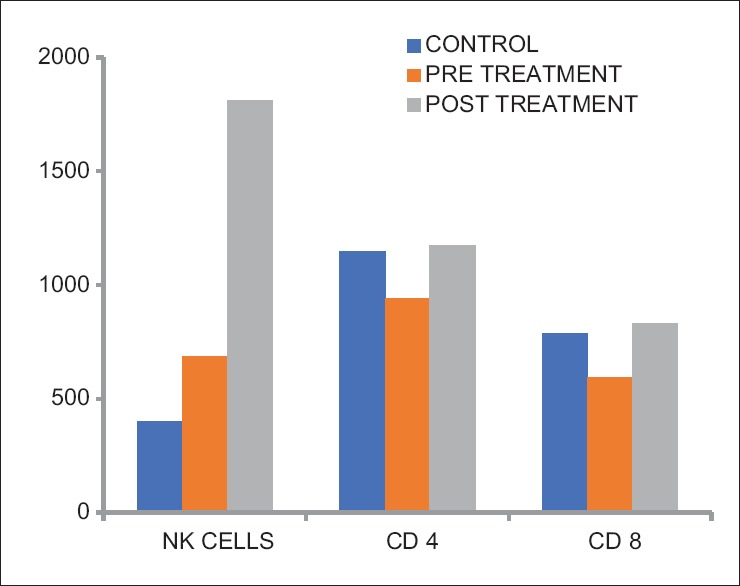

Comparison of the cell-mediated immune markers revealed NK cells to be significantly higher in the depressed group than in the control group (P ≤ 0.001). The CD4 Cells were significantly higher in the control group than in the depressed group (P = 0.003). CD8 Cells were also significantly higher in the control group than in the depressed group (P = 0.001). There was no significant difference between the CD4 and CD8 ratios [Table 1 and Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Comparison of cell-mediated immune markers in control group and depressed patients before and after treatment

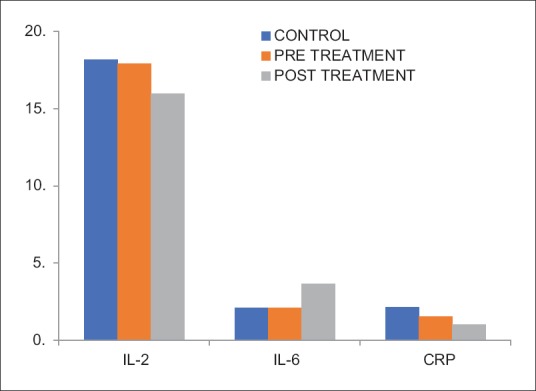

Comparison of the humoral immune markers revealed that the IL-2 levels (in pg/ml) were higher in the control group than in the depressed group though it did not differ significantly (P = 0.586). IL-6 levels (in pg/ml) were marginally higher in the depressed group than in the control group, and the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.973). CRP levels (in μg/ml) were higher in the depressed group than in the control group and differed significantly (P ≤ 0.001) [Table 1 and Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Comparison of humoral immune markers in control group and depressed patients before and after treatment

Comparison of the psychometric and immunological parameters of depressed patients before treatment and after treatment revealed that the mean HRSD and BDI scores had reduced significantly in the depressed patients after 8 weeks of treatment (P ≤ 0.001) [Table 1]. The markers of cell-mediated immunity: NK cells, CD4, and CD8 had all increased significantly following treatment (P ≤ 0.001). However, there was a fall in the CD4:CD8 ratio though the difference was not significant (P = 0.023) [Table 1 and Figure 1]. The humoral immunity markers showed highly significant fall in CRP and IL-2 levels in depressed patients after treatment (P ≤ 0.001). IL-6 levels were raised significantly in the patients after antidepressant treatment (P ≤ 0.001) [Table 1 and Figure 2].

DISCUSSION

Immunological changes in depressed persons have been reported by numerous studies.[13,14,19] However, even meta-analysis have questioned whether there are consistent changes in cellular and humoral immunity in depression.[5] This is due to the heterogeneity of depression and the numerous moderating clinical and biological factors which may account for the lack of consistency in results.

Previous studies report higher prevalence and incidence of depression in women.[1] The smaller number of females in this study was because the hospital where the study was conducted allows admission of only male inpatients in the psychiatry ward.

Comparison of depression rating scores using HRSD and BDI showed significantly higher mean scores in the depressed group compared to controls at baseline (P = 0.00). The HRSD and BDI scores were significantly lower in the depressed group after 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment (P = 0.00) [Table 1].

When cellular immunity was evaluated, the mean NK cells were noted to be significantly higher in the depressed group before treatment compared to healthy matched controls (P = 0.00). Most other studies have reported mild reductions in absolute NK cell counts in depressed individuals.[20] However, a study found circulating NK cells were elevated in depressive illness and varied as a function of depressive subtype and sex.[21]

The mean NK cell counts in depressed group posttreatment were significantly higher than before treatment. This is in agreement with other studies which have suggested that depression leads to suppression of the cellular immunity which resolves with antidepressant treatment.[22,23]

In the present study, the mean CD4 and CD8 cells were significantly lower in the depressed group before treatment compared to healthy matched controls. This finding is in agreement with studies which revealed decreased CD4 counts.[13,24] However, a few studies have found increase in CD4 counts in depressed individuals.[5,25] Since 2001, most studies have reported an increase in CD4 levels. It has been reported that in acute stress the CD8 cell counts are increased, while in chronic stress, both CD4 and CD8 counts are decreased and there were no significant differences in CD4 and CD8 counts in depression.[19] Probably, it would have been easier to substantiate these findings if the assessment of stressors was carried out. However, the finding of immunosuppression as regards cellular immunity in depression is supported by evidence such as patients with major depression have been noted to have a marked decrement in their ability to generate lymphocytes that respond to the herpes zoster virus.[20]

The mean CD4 and CD8 cell counts in depressed group posttreatment were significantly higher than before treatment. This is in agreement with other studies which have suggested that depression is an immunosuppressive state with regard to cellular immunity, which normalizes after depression resolves.[26]

In this study, mean IL-2 levels were found to be marginally decreased in depressed as compared to healthy controls and this difference was not statistically significant. Elevation in IL-2 (a pro-inflammatory cytokine) production in depressed individuals has been noted by other authors.[27] Following antidepressant treatment, significant decrease in IL-2 levels was found in this study. This is in agreement with other studies.[28] The reason proposed is that antidepressant therapy exerts an immunomodulatory effect through decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines and also an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and TGF-β1.

Findings of the present study did not note any significant difference in the mean IL-6 levels between depressed patients and control. This finding is contrary to what has been reported in most literature, wherein IL-6 levels have been reported to be increased in depressed subjects.[29] There was significant rise in IL-6 levels in depressed patients following antidepressant treatment, which is again contrary to what has been found in other studies. However, a study has reported that depressed patients who respond to antidepressant treatment had lower IL-6 levels which increased after treatment, while those who did not respond to antidepressant medication had higher IL-6 levels at baseline.[30] This agrees with our study as our patients had responded well to antidepressants and had lower IL-6 levels at baseline which increased after antidepressant therapy. This leads to an interesting conjecture that IL-6 levels could be predictors of response to therapy and merits further research.

This study found significantly higher mean levels of CRP in depressed patients compared to controls. Since depression is assumed to be a pro-inflammatory condition as per the cytokine theory of depression, CRP levels would be expected to be raised. Following treatment with antidepressants, CRP levels decreased significantly in the posttreatment-depressed patients as compared to the pretreatment group. This finding is also in agreement with other reported studies.[5,9,31]

Depression itself remains a difficult disorder to the study. Most likely, it represents a heterogeneous group of disorders, which may each have different biological profile. It is interesting to hypothesize how subgroups of depression, such as psychotic, bipolar, neurotic, or melancholic depression, might have different immune mechanisms or profiles.[32] It is still unclear whether altered markers of immunity, especially the cytokines, are responsible for the provocation of depression or merely represent an effect of depression on various systems in the body.

Limitations of the study

There are certain limitations of the study such as small sample size (cost being a major factor) and different antidepressants being used

There was heterogeneity of sample, wherein depression has been taken to be a unitary diagnosis including cases of dysthymia, rather than being subclassified into various types of depressive disorder.

There are many confounding variables in the study as immunological changes which have been reported in depression are often influenced by health-related behavior such as sleep, exercise, smoking, alcohol, stress, and medical comorbidities. The above notwithstanding, this study is important as there is no data available in Indian literature on the wide variety of immune parameters considered together, both before and after treatment, as in the present study.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study has shown that there is a change in cell-mediated and humoral immunity in depressed patients. Further, antidepressant treatment affects the immune status of depressed patients.

The implications of this study are that since there is immune dysregulation in depression, immunomodulator group of drugs might have a role in the management of depression in future. Furthermore, the pro-inflammatory changes noted in depression may merit consideration of a prospective role for anti-inflammatory drugs in its management. There is already research underway into these aspects of depression, and the result from studies such as this one could indeed change or revolutionize the pharmacological management of depression in the years ahead. TNF antagonist infliximab does not have generalized efficacy in treatment-resistant depression but may improve depressive symptoms in patients with high baseline inflammatory biomarkers.[33] Use of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid may represent an adjunctive antidepressant treatment option.[34] Thus, recent research is exploring fascinating new treatment options for depression.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to the Office of the Director General Armed Forces Medical Services for permitting this study and providing the funds. The contribution of Brig RM Gupta, Professor, Department of Microbiology, AFMC, Pune, without whose help this study would not be feasible, is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rihmer Z, Angst A. Mood disorders: Epidemiology. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan & Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. New Delhi: Walter Kluwer Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiepers OJ, Wichers MC, Maes M. Cytokines and major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:201–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller GE, Rohleder N, Stetler C, Kirschbaum C. Clinical depression and regulation of the inflammatory response during acute stress. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:679–87. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000174172.82428.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavanagh J, Mathias C. Inflammation and its relevance to psychiatry. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2008;14:248–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zorrilla EP, Luborsky L, McKay JR, Rosenthal R, Houldin A, Tax A, et al. The relationship of depression and stressors to immunological assays: A meta-analytic review. Brain Behav Immun. 2001;15:199–226. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2000.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin M, Daniels M, Smith TL, Bloom E, Weiner H. Impaired natural killer cell activity during bereavement. Brain Behav Immun. 1987;1:98–104. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(87)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: Inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP. Obesity-related sleepiness and fatigue: The role of the stress system and cytokines. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1083:329–44. doi: 10.1196/annals.1367.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller GE, Freedland KE, Duntley S, Carney RM. Relation of depressive symptoms to C-reactive protein and pathogen burden (cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr Virus) in patients with earlier acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:317–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenis G, Maes M. Effects of antidepressants on the production of cytokines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5:401–12. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702003164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien SM, Scott LV, Dinan TG. Cytokines: Abnormalities in major depression and implications for pharmacological treatment. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:397–403. doi: 10.1002/hup.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wichers MC, Koek GH, Robaeys G, Praamstra AJ, Maes M. Early increase in vegetative symptoms predicts IFN-alpha-induced cognitive-depressive changes. Psychol Med. 2005;35:433–41. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schleifer SJ, Keller SE, Bond RN, Cohen J, Stein M. Major depressive disorder and immunity. Role of age, sex, severity, and hospitalization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:81–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810010083011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pace TW, Mletzko TC, Alagbe O, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH, et al. Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1630–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisse CS. Depression and immunocompetence: A review of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:475–89. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Classification of Diseases ICD-10. 10th Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbert TB, Cohen S. Stress and immunity in humans: A meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:364–79. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schleifer SJ, Keller SE, Bartlett JA. Depression and immunity: Clinical factors and therapeutic course. Psychiatry Res. 1999;85:63–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravindran AV, Griffiths J, Merali Z, Anisman H. Lymphocyte subsets associated with major depression and dysthymia: Modification by antidepressant treatment. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:555–63. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199511000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cover H, Irwin M. Immunity and depression: Insomnia, retardation, and reduction of natural killer cell activity. J Behav Med. 1994;17:217–23. doi: 10.1007/BF01858106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank MG, Hendricks SE, Burke WJ, Johnson DR. Clinical response augments NK cell activity independent of treatment modality: A randomized double-blind placebo controlled antidepressant trial. Psychol Med. 2004;34:491–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herbert TB, Cohen S. Depression and immunity: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:472–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller N, Schwarz MJ, Dehning S, Douhe A, Cerovecki A, Goldstein-Müller B, et al. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib has therapeutic effects in major depression: Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled, add-on pilot study to reboxetine. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:680–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonard BE. The immune system, depression and the action of antidepressants. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001;25:767–80. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlatter J, Ortuño F, Cervera-Enguix S. Lymphocyte subsets and lymphokine production in patients with melancholic versus nonmelancholic depression. Psychiatry Res. 2004;128:259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia Z, DePierre JW, Nässberger L. Tricyclic antidepressants inhibit IL-6, IL-1 beta and TNF-alpha release in human blood monocytes and IL-2 and interferon-gamma in T cells. Immunopharmacology. 1996;34:27–37. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(96)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janssen DG, Caniato RN, Verster JC, Baune BT. A psychoneuroimmunological review on cytokines involved in antidepressant treatment response. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:201–15. doi: 10.1002/hup.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanquillon S, Krieg JC, Bening-Abu-Shach U, Vedder H. Cytokine production and treatment response in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:370–9. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castanon N, Leonard BE, Neveu PJ, Yirmiya R. Effects of antidepressants on cytokine production and actions. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:569–74. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothermundt M, Arolt V, Peters M, Gutbrodt H, Fenker J, Kersting A, et al. Inflammatory markers in major depression and melancholia. J Affect Disord. 2001;63:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raison CL, Rutherford RE, Woolwine BJ, Shuo C, Schettler P, Drake DF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the tumor necrosis factor antagonist infliximab for treatment-resistant depression: The role of baseline inflammatory biomarkers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:31–41. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Köhler O, Petersen L, Mors O, Gasse C. Inflammation and depression: Combined use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and NSAIDs or paracetamol and psychiatric outcomes. Brain Behav. 2015;5:e00338. doi: 10.1002/brb3.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]