Abstract

Background:

Depressed patients are preoccupied with unhappy thoughts which reduce their capacity to focus on attention, memory, and other cognitive performance.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to assess neuropsychological deficits in elderly depressive and compare it with matched normal controls.

Methods:

After consideration of inclusion and exclusion criteria, the sample of 30 elderly depressive patients diagnosed on the basis of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition criteria and 30 normal controls were selected. The selection of sample was by purposive sampling from private psychiatric clinic of Bhopal. The age range of sample was 60 years and above. All participants were administered the Geriatric Depression Scale, and the Luria–Nebraska Neuropsychological Battery-1 (LNNB form-1).

Results:

On the Geriatric Depression Scale, 21 patients were at mild level and nine patients were at severe level of depression. None of the normal controls were depressed. On LNNB form-1, depressive patients showed significant elevation on receptive speech, arithmetic, memory, reading, writing, and expressive speech as compared to normal controls.

Conclusion:

Older depressive patients showed significantly more neurocognitive deficits as compared to normal controls. It is important that these deficits are identified and addressed for the holistic treatment of late-onset depression.

Keywords: Geriatric depression, Luria Nebraska Neuropsychological Battery form-1, neuropsychological deficits

The ageing process is a biological reality which has its own dynamic, largely beyond human control. Old age is a phase of the life cycle characterized by its own developmental issues, many of which are concerned with loss of physical agility, and mental acuity, friends and loved ones, and status and power. Internationally, the prevalence of depression and cognitive impairment in geriatric participants is estimated to be 11%–30%[1,2] and 17%–36%,[2,3,4] respectively. Therefore, though depression is primarily a mood disorder, for many older adults, it is also a cognitive disorder. Elderly depressives with comorbid cognitive impairment are a particular clinical concern because it increases the rate of adverse outcomes for physical health, functional status, and mortality.[5]

There has been a renewal of interest in testing patients' with depression on a broad range of neuropsychological tasks in the last decade. This has promoted a growing awareness that, like schizophrenia and other neurological disorders, mood disorders may be associated with a distinct pattern of cognitive impairment. Such impairments of cognitive function are seldom measured. This is surprising because it is easier objectively to measure memory impairment, for example, than it is to measure other core feature of depression in old age such as the severity of depressed mood or sleep disturbance. However, also central to current interest is the effort to link theories of cognitive neuropsychology to the anatomy and physiology of brain function. If depression is indeed a brain disease, then neuropsychological impairments may lead us to the relevant neural substrates. It is now commonly accepted that depression with age is associated with a number of deficits in episodic memory and learning.[6] This finding is consistent across most studies and appears to involve both explicit verbal and visual memory in patients with both melancholic endogenous and nonmelancholic nonendogenous depression.[7] Implicit memory tasks, on the other hand, appear to be spared.[8,9,10,11] Temporal lobe lesions typically disrupt episodic memory; given that reductions in hippocampal volume are demonstrated in patients with major depression, it may be that impaired mnemonic function is associated with dysfunction of the hippocampus in depression.[12] Depression with cognitive impairment is among the most important mental health problem which occurs in elderly people. In both conditions, the patients have severe consequences, including diminished quality of life, functional decline, increased use of services, and high mortality.

Late-onset depression and cognitive impairment often occur together, suggesting a close association between them. It is not known, however, whether depression leads to cognitive decline or vice versa. Clinical practice and research evidence suggest that depression precedes cognitive decline in old age. However, inferring a relationship is hampered because most studies on this topic examined only the association between depression and the subsequent development of cognitive impairment. Thus, the present study was undertaken to assess the neuropsychological deficits in elderly depressive and compare it with matched normal controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The sample consisted of thirty elderly depressive patients diagnosed on the basis of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition-Diagnostic Criteria for Research[13] criteria and age range of 60 and above with minimum of 2 years of illness and free from comorbid psychiatric or major medical illnesses. Equal number of age- and sex-matched control participants without any psychiatric or physical illnesses formed the control group. All participants were explained the aim of the study and gave informed consent.

Sampling technique

Sampling technique was purposive sampling. Patients were selected from private clinics of Bhopal.

Tools used for assessment

Procedure

After screening according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, patients were selected for study. Clinical interview and required history were taken and sociodemographic sheet was filled. GDS was administered to assess the depression in elderly. LNNB-I was administered in 2–3 sessions over a period of 1 day of 2 consecutive days on both depressive and normal controls.

The tests were scored as per the test manuals. Statistical analyses were carried out using Chi-square test and Student's t-test as appropriate.

RESULTS

The mean and standard deviation (SD) of age of normal and depression patients was 62.66 (±2.08) years and 63.46 (±2.40) years, respectively. The mean and SD of education level of normal and depressive patients was 13.2 ± 2.97 years and 11.8 ± 3.42 years, respectively. All the participants were male, married, from urban area, and right handed. There were no significant differences between the depressive patients and normal controls on the sociodemographic characteristics.

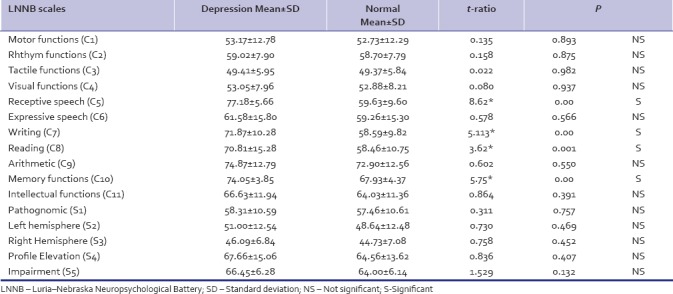

On the GDS, 21 patients were at mild level and nine patients were at severe level of depression. None of the normal controls were depressed. The mean critical level of LNNB-I profile of normal and depressive was 61.9 and 64.23 levels, respectively. On LNNB-I depressed elderly participants showed significantly poorer performance than normal on receptive speech, writing, reading, arithmetic, and memory [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison between elderly depression and matched control subjects on Luria-Nebraska Neuropsychological Battery-I

DISCUSSION

The study reveals that depressive patients underwent a general cognitive decline which is evidenced by differences in neuropsychological test performance relative to normal controls on LNNB-I; performance differences were especially in domain of receptive speech, reading, writing, and memory. The poor performance of depressive patients compared to the normal controls in the present study indicates that probably depressive symptoms are associated with cognitive decline which is supported by the findings of earlier studies.[16,17] A meta-analytic study also concluded that a motivation deficit has the potential to impair the performance of all neuropsychological tasks in depression.[18]

Cognitive functions are associated with symptoms of depression. Functional imaging and brain stimulation studies have convincingly proved that dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VmPFC) play significant roles in the pathophysiology of depression. Apart from playing an important role in the generation of negative emotion, through its projections to amygdala and hypothalamus, VmPFC also coordinates the negative emotions.[19] Studies suggest that DLPFC-mediated cognitive control functions, memory, learning, attention executive functions, also pertain to emotion. Specifically, functional imaging studies demonstrate the recruitment of DLPFC during the regulation of negative emotion through reappraisal/suppression strategies.[20] Studies associate depression with abnormally high levels of VmPFC activity[21,22] but abnormally low levels of DLPFC activity,[23,24,25] thus affecting cognitive functions. This could explain the findings of the present study where patients with depression showed poor performance on LNNB-I scale.

The mean critical level of LNNB-I profile of depressive and normal were 64.2 and 61.9 levels, respectively. On LNNB-I, depressive patients show significantly poorer performance than normal controls which is clear from Table 1 which indicates that LNNB-I profile of depressive shows elevation on scales above the critical level, namely, receptive speech, writing, reading, arithmetic, and memory. However, LNNB-I profile of normal participants shows scale above the critical levels, namely, arithmetic, memory, and intellectual scales. Thus, it was found from the present study that although there was elevation on mean profile of both the groups, a significant difference was obtained between both the groups only on receptive speech, writing, reading, and memory scales. The above findings are consistent with the findings of an earlier study which found that in comparison to controls, depression is associated with a number of deficits in episodic memory and learning.[26] Another recent study also noted deficit in immediate verbal memory, short-term memory, and working memory of major depressive patients with increasing age.[27] Earlier studies have also reported that depressives showed impairments in complex integration for concept formation, spontaneous cognitive flexibility, initiation ability,[28] and have poor performance strategies in comparison with controls.[29]

In the present study, depressive had poor performance than normal control on memory functions and also had problem in new learning and recall interference which indicates that during depressive stage, patients are unable to carry out cognitive functions properly. This is consistent with findings of a recent study which found a significant variation in performance between depressive patients and normal controls in most cognitive functions, especially memory (P < 0.0001), semantic fluency (P < 0.0001), verbal fluency, and digit symbol (P < 0.0001). Late-onset depression patients scored lower and exhibited more severe impairment in memory domains than early-onset depression patients (P < 0.05). Both depressed groups, early and late onset, were more inactive than controls (P < 0.05; odds ratio: 6.02).[30] Depressive symptoms may be a prodrome of cognitive decline, the early manifestation of a neurodegenerative process, causing depression, and dementia. Depression with onset after 60 years of age is associated with pathology of subcortical and deep white matter structures[31] and is more frequently associated with cognitive impairment, typically with prominent abnormalities in executive function that reflect underlying disruption of frontostriatal circuits.[32,33,34,35]

CONCLUSION

Elderly patients with depression have significantly more neurocognitive deficits as compared to age-matched nondepressed controls. It is important that these deficits are identified and addressed for the holistic treatment of late-onset depression.

Limitations

The study had various limitations. The sample size was small. Females could not be included in the study which is a primary limitation in the applicability of the present findings to female depressive patients. A structured clinical interview was not conducted for making psychiatric diagnosis. Being a cross-sectional study, we could not conclude whether depression leads to cognitive dysfunction or vice versa. Neuroradiological investigations would have added to better inference.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Copeland JR, Beekman AT, Braam AW, Dewey ME, Delespaul P, Fuhrer R, et al. Depression among older people in Europe: The EURODEP studies. World Psychiatry. 2004;3:45–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee Y, Shinkai S. Correlates of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms among older adults in Korea and Japan. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:576–86. doi: 10.1002/gps.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rait G, Fletcher A, Smeeth L, Brayne C, Stirling S, Nunes M, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment: Results from the MRC trial of assessment and management of older people in the community. Age Ageing. 2005;34:242–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graciani A, Banegas JR, Guallar-Castillón P, Domínguez-Rojas V, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Cognitive assessment of the non-demented elderly community dwellers in Spain. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21:104–12. doi: 10.1159/000090509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Langa KM, Sands L, Whooley MA, Covinsky KE, et al. Additive effects of cognitive function and depressive symptoms on mortality in elderly community-living adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:M461–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.5.m461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin GM, Austin MP, Dougall N, Ross M, Murray C, O'Carroll RE, et al. State changes in brain activity shown by the uptake of 99mTc-exametazime with single photon emission tomography in major depression before and after treatment. J Affect Disord. 1993;29:243–53. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90014-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austin MP, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, Parker G, Hickie I, Brodaty H, et al. Cognitive function in depression: A distinct pattern of frontal impairment in melancholia? Psychol Med. 1999;29:73–85. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hertel PT, Hardin TS. Remembering with and without awareness in a depressed mood: Evidence of deficits in initiative. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1990;119:45–59. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.119.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denny EB, Hunt RR. Affective valence and memory in depression: Dissociation of recall and fragment completion. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:575–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danion JM, Kauffmann-Muller F, Grangé D, Zimmermann MA, Greth P. Affective valence of words, explicit and implicit memory in clinical depression. J Affect Disord. 1995;34:227–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00021-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilsley JE, Moffoot AP, O'Carroll RE. An analysis of memory dysfunction in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1995;35:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00032-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheline YI, Wang PW, Gado MH, Csernansky JG, Vannier MW. Hippocampal atrophy in recurrent major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3908–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders, Diagnostic criteria for Research. Geneva: WHO; 1993. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golden CJ, Purish AD, Hammeke TA. Luria – Nebraska Neuropsychological Battery: Forms I & II (Manual) Los Angeles Western Psychological Services. 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Köhler S, Thomas AJ, Barnett NA, O'Brien JT. The pattern and course of cognitive impairment in late-life depression. Psychol Med. 2010;40:591–602. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priyamvada R, Jahan M. Cross validity of 22-items and 15-items screening tests from LNNB-1on depressive patients. Indian J Clin Psychol. 2009;36:84–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austin MP, Mitchell P, Goodwin GM. Cognitive deficits in depression: Possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:200–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ongür D, Price JL. The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, monkeys and humans. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:206–19. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochsner KN, Bunge SA, Gross JJ, Gabrieli JD. Rethinking feelings: An FMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14:1215–29. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drevets WC, Videen TO, Price JL, Preskorn SH, Carmichael ST, Raichle ME, et al. A functional anatomical study of unipolar depression. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3628–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03628.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45:651–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biver F, Goldman S, Delvenne V, Luxen A, De Maertelaer V, Hubain P, et al. Frontal and parietal metabolic disturbances in unipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;36:381–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)91213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baxter LR, Jr, Schwartz JM, Phelps ME, Mazziotta JC, Guze BH, Selin CE, et al. Reduction of prefrontal cortex glucose metabolism common to three types of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:243–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810030049007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galynker II, Cai J, Ongseng F, Finestone H, Dutta E, Serseni D, et al. Hypofrontality and negative symptoms in major depressive disorder. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:608–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodwin GM. Neuropsychological and neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal lobes in depression. J Psychopharmacol. 1997;11:115–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119701100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mondal S, Sharma VK, Das S, Goswami U, Gandhi A. Neurocognitive function in patients of major depression. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;51:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fossati P, Amar G, Raoux N, Ergis AM, Allilaire JF. Executive functioning and verbal memory in young patients with unipolar depression and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1999;89:171–87. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Channon S, Green PS. Executive function in depression: The role of performance strategies in aiding depressed and non-depressed participants. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:162–71. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillon C, Allegri RF, Serrano CM, Iturry M, Salgado P, Glaser FB, et al. Late- versus early-onset geriatric depression in a memory research center. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:517–26. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s7320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan KR, Hays JC, Blazer DG. MRI-defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:497–501. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexopoulos GS, Kiosses DN, Klimstra S, Kalayam B, Bruce ML. Clinical presentation of the “depression-executive dysfunction syndrome” of late life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:98–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butters MA, Whyte EM, Nebes RD, Begley AE, Dew MA, Mulsant BH, et al. The nature and determinants of neuropsychological functioning in late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:587–95. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potter GG, Steffens DC. Contribution of depression to cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults. Neurologist. 2007;13:105–17. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000252947.15389.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas P, Hazif Thomas C, Billon R, Peix R, Faugeron P, Clément JP, et al. Depression and frontal dysfunction: Risks for the elderly.? Encephale. 2009;35:361–9. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]