Abstract

Background:

The definitive diagnosis of depression calls for fulfillment of certain criteria in terms of symptoms, severity, and duration, but subthreshold cases are not uncommon. These may evolve to become clinically diagnosable depression preceded by prodrome. The current study was conducted to study prodromal and residual symptoms in depression.

Materials and Methods:

Eighty follow-up patients of depressive episode (F32, International Classification of Diseases-10) in remission defined by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score <8 were interviewed. A symptom was identified as prodromal if it appeared at any time before the period of onset of symptoms sufficient to fulfill the criteria to make a diagnosis of depressive episode. Clinical Interview for Depression and Related Syndromes was used to identify the presence of symptoms. Statistical analysis was done with McNemar test and Pearson's Chi-square test using SPSS software version 20.0.

Results:

The mean age of patients was 41.25 (±8.58) years and the sample was predominately female patients (80%). All the eighty patients had at least one prodromal symptom. The mean duration of prodrome was 115 (±64.46) days. Irritability (45%), insomnia (45%), and reduced energy (43.8%) were the most frequent prodromal symptoms. Frequency of irritability was comparable in prodromal and residual phases of depression (P = 0.074) and significantly associated with a positive family history of depression (P = 0.004).

Conclusion:

Prodrome is present in most cases of depression lasting from weeks to months. Prodrome is frequented by irritability, anxiety, sleep problems, and fatigability. Irritability is associated with genetic loading of depression and likely to present as residual symptom if it is present in prodromal phase.

Keywords: Depressive disorder, irritable mood, prodromal symptoms, residual symptoms

The term depression has been used widely to describe an emotional state, a syndrome, and a group of specific disorders. When seen as part of a syndrome or disorder, depression has emotional, cognitive, somatic, perceptual, and behavioral manifestations. Depression is one of the most common disorders affecting humankind and therefore is a widely researched topic for managing it effectively. Despite multiple effective therapies, biological as well as nonbiological, depression remains a highly prevalent, disabling, and costly condition. The World Health Organization identifies depression as the leading cause of disability worldwide and contributes to suicide as well[1] and is expected to be the second highest cause of morbidity worldwide by 2020.[2]

Like many other chronic medical conditions, many cases remain undetected for years or inadequately controlled, increasing the suffering of patients' and caregiver burden, reducing productivity, and increasing the cost of care when severity reaches to its peak. For the sake of simplicity of diagnosis and management strategies of depression, the diagnostic criteria are devised in classification systems such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and DSM. The peculiarity about these criteria is the threshold about the number of symptoms, severity, as well as duration for a patient, which needs to be crossed to warrant an acceptable diagnosis on the classification systems of disease. However, it is not uncommon in clinical practice to encounter cases which have subthreshold clinical picture before the patients are diagnosed of depressive episode. This is referred to as the prodrome. This sort of subthreshold symptoms can last for a considerable duration in some patients and may cross the threshold eventually with or without stressors to manifest as clinical depression. A subset of chronically depressed individuals may also have temperamental, biologically driven depression, often seen in conjunction with strong genetic loading for severe mood disorders.[3] The prodrome can be considered an early marker of depression and probably biologically determined. Various studies[4,5] have also revealed other subsyndromal conditions, i.e., oligosymptomatic mood states and of short duration (brief episodes), variously referred to as minor, subsyndromal, brief, or intermittent, increasing the importance of early detection of at-risk individuals, as in diabetes mellitus and essential hypertension.

Mood instability such as sudden and intense mood changes over a relatively short time is argued to be a precursor to depression although it remains a feature largely experienced but equally subjective due to lack of uniform definition.[6] The neurobiological correlates of the mood instability are not completely deciphered and current evidences are suggestive of amygdala and prefrontal cortex-related abnormality.[7]

The term “prodrome” derives from the Latin word “prodromus,” which in turn stems from the Greek “prodromos.” It indicates the forerunner of an event (e.g., a race). In medicine, prodromes can be identified with the early symptoms and signs that differ from those of acute clinical phase. The prodromal period generally refers to the time interval between the onset of the first prodromal symptom and onset of the characteristic signs/symptoms of the fully developed illness.[8] Anxiety/tension, irritability, loss of interest, sleep disturbance, decreased drive or motivation, emotional distance, depressed mood, gastrointestinal problems, fatigue, impaired concentration, and decreased energy are reported as prodromal symptoms in patients of depressive disorders.[9]

Understanding how a disorder, especially an episodic one, will unfold and eventually remit over time can be invaluable for understanding the course of the disorder even before the emergence of a complete clinical picture. The identification of prodromes helps planning an early intervention and preventive strategies in individuals as well as gives a clue to the probability of development of clinically significant depression as a full-fledged syndrome, thereby minimizing the impact of a depressive episode and improving the quality of life. This study aims to describe the prodrome and residual symptoms in depressive disorder.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and sample

The study is conducted at the psychiatry outpatient department of a tertiary care municipal-run teaching hospital in a city of India. Consecutive sampling was used to collect the study sample. Eighty follow-up outpatients fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were interviewed for the purpose of study between March 2013 and February 2014. The data were obtained from the patient, the caregiver, as well as the past medical records wherever available.

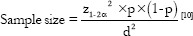

Z1−2α=1.96 (value for 95% confidence level); P = 0.045 (4.5% prevalence,[11] expressed as decimal); and C = 0.05 (confidence interval, expressed as decimal). The estimated sample comes around 60.

Ethics

The study protocol was presented to the institutional ethics committee and was approved before commencement of the study. Patients with depression followed up in the psychiatry outpatient department were briefed about the study, assured confidentiality, and written informed consent was obtained from the willing participants before commencing the interview. Confidentiality was maintained using unique identifiers.

Selection criteria

The follow-up patients of depressive episode (ICD-10, F32) with onset not <2 years before the date of interview, between 18 and 60 years of age, were included in the study. All the participants were to be functional for at least a month prior to interview and in remission as defined by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score within normal range (0–7). Patients with any chronic and debilitating medical or neurological illness and any current or past psychiatric condition apart from depressive episode (ICD-10, F32) were not included in the study. Patients with comorbid substance use disorder in dependence pattern other than nicotine and caffeine were excluded from the study.

Data collection

All the follow-up patients during the said period were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study. The patients fulfilling the requirements of participation of study were briefed about the study and written informed consent was obtained from the willing patients before they were enrolled in the study. Participants enrolled for the study were given convenient appointment and called for interview along with relevant medical records and one relative wherever possible to obtain objective data. Information from patients, relatives, and medical records had been used to ascertain the onset of first prodromal symptom, as well as the onset of the full-blown episode. Following were the instruments used for data collection:

A case record form to record relevant sociodemographic and clinical details

HAM-D: It is a multiple-choice questionnaire that clinicians may use to rate the severity of a patient's depression. The questionnaire rates the severity of depressive symptoms such as low mood, sleep disturbances, and anhedonia to name a few. The scale contains 17 variables and the score is calculated by adding the score on each variable. Score <8 is considered normal, 8–13 is suggestive of mild depression, 14–18 of moderate depression, 19–22 of severe depression, and more than 22 of very severe depression. Internal consistency is reported 0.83[12] and validity ranges from 0.65 to 0.90[13]

-

Clinical Interview for Depression and Related Syndromes (CIDRS):[13] It has been developed on the basis of modern psychometric interpretations of the relationship between symptom and syndrome.

CIDRS is constructed so that it is possible to extract the most commonly used scales (Hamilton's Anxiety Scale, HAM-D, the Montgomery–Šsberg Depression Rating Scale, Young's Mania Scale, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, and Bipolar Depression Rating Scale). The CIDRS interview consists of the modules for Anxiety, Depression, Mania, Schizophrenia, Supplementary items, Etiological considerations.[14]

A symptom was identified as prodromal if it appeared at any time before the period of onset of symptoms sufficient to fulfill the criteria to make a diagnosis of depressive episode according to ICD-10 and remained consistently present into the acute phase. Accordingly, the prodromal phase was operationally defined as the period of time before the acute phase during which at least one symptom was continuously present. The duration between the occurrence of the first prodromal symptom and the onset of the diagnosable depressive episode was regarded as the duration of the prodrome. Similarly, residual symptom was defined as a symptom continuously present for at least 2 weeks before the time of interview despite the HAM-D score within normal range.

Patients and relatives were also inquired about premorbid traits and residual symptoms if any so that it can be distinguished from prodromal symptoms. All information had been cross-checked from records, wherever available; any discrepancies had been resolved by additional interviews. Case record form was filled in with relevant sociodemographic and clinical details of the participant. HAM-D was used to assess the severity of depression and defining remission. After that, the CIDRS was applied on patients to identify if the prodromal symptoms were present or absent and data were collected. The case record form of each participant was coded serially to ensure confidentiality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 20.0 was applied to obtain statistical significance of the data thus collected. Descriptive statistics had been used to describe the sample in terms of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. The occurrence of prodrome and residual symptoms was compared using McNemar test. Pearson's Chi-square test was used to compare between groups based on gender and family history of depression. In this study, a level of significance (α) of <0.05 (two tailed) has been taken to consider a statistically significant result.

RESULTS

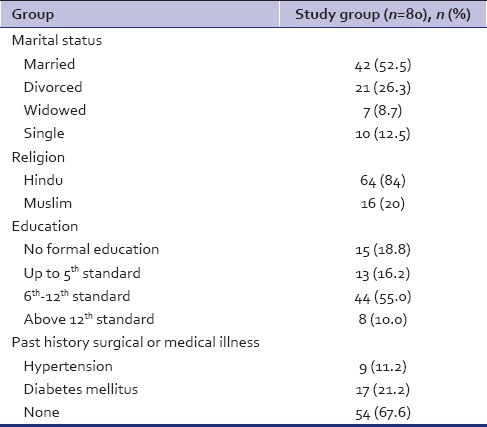

We interviewed a total of eighty patients for the study with a mean age of 41.25 (±8.58) years and the sample was predominated with female patients (80%). Majority of the patients among our sample were married and did not attend college for education [Table 1]. More than two-third of the patients had no comorbid medical condition [Table 1] and there was a positive family history of psychiatric illness in 45% of the patients.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic details of the patients

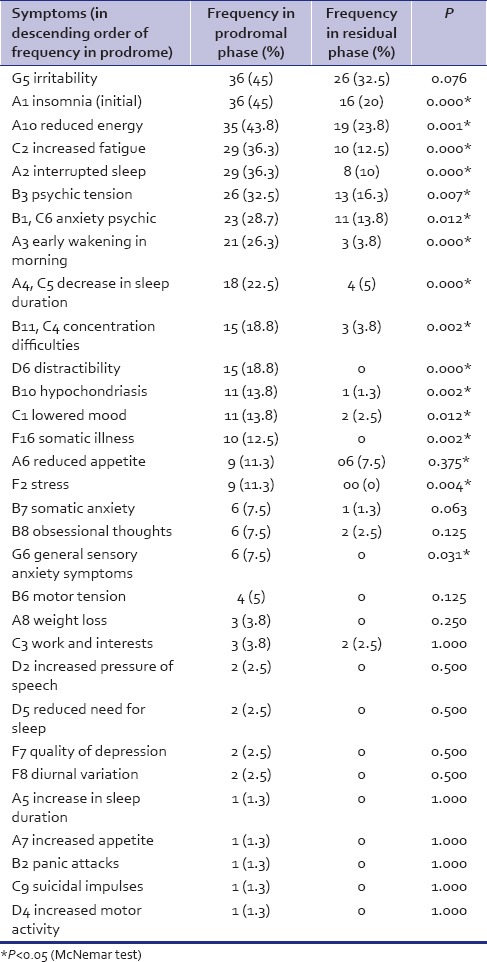

All the patients interviewed had revealed some or other symptoms as prodrome, whereas 10% of participants denied any form of residual symptoms. Mean duration of prodrome was 115 (±64.46) days, ranging from 20 to 300 days. Irritability remained the most commonly reported symptom in the prodromal as well as the residual phases of our study sample, closely followed by insomnia (initial) and reduced energy [Table 2]. Neurovegetative symptoms (Module A) were the most common symptom cluster in both prodromal and residual phases, whereas anxiety (Module B) and depressive (Module C) symptoms were also commonly reported as prodromal symptoms by the participants. There was a significant difference between the most common prodromal and residual symptoms with the exception of irritability [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of symptoms during prodromal and residual phases

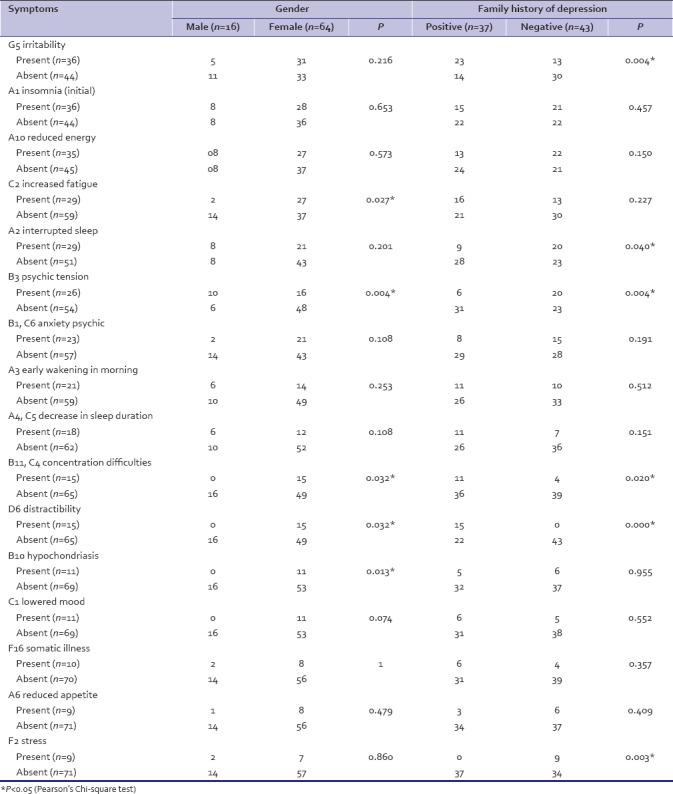

We compared the symptoms of prodrome, with at least 10% frequency in our sample between male and female participants. We found that females significantly often had increased fatigue, concentration difficulties, distractibility, hypochondriasis and males had psychic tension. When the same symptoms were compared between those with a positive family history of depression and those without, we came across a few significant differences as well. Irritability, concentration difficulty, and distractibility were present significantly often in those with a positive family history of depression [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of prodromal symptoms between groups based on gender and family history of depression

DISCUSSION

The current study was undertaken with the objective to study the prodrome of depressive episode as well as comparing prodrome with residual symptoms. Furthermore, we intended to find out if and when the specific prodrome can be defined in terms of symptoms in different associated factors such as gender, age, medical comorbidity, and family history of depression.

Different researchers have studied the prodrome and duration of prodrome and it is reviewed to range from 7 to 133 days for cases of major depression,[9] whereas in mixed sample of unipolar and bipolar disorders, the median duration of prodrome was 28 days.[15] Fava et al.[16] in their preliminary study reported that at least one prodromal symptom is present in 100% of the depressed patients before the onset of depressed mood. A recent investigation[4] describes that around 10% of patients presenting in outpatient department were diagnosed with subthreshold depression, making it a significant morbidity. Our investigation fairly agrees with this view with a comparable duration of prodrome and 100% incidence of at least one prodromal symptom in cases of depressive episode. Jackson et al. reviewed that patients who get relapse of depression can identify at least one symptom before relapse in four out of five cases.[9] We could not agree more about emphasizing and investigating this subsyndromal and prodromal phenomenon of depressive episode.

Our study suggests irritability, reduced energy, fatigue, sleep problems, psychic tension, and anxiety to be the common prodromal symptoms to name a few. In addition, when residual symptoms are looked at, a similar symptom picture is visible with some variations. Fava et al. identified generalized anxiety and irritability to be the most common prodromal symptoms.[16] Recently, a longitudinal study[17] investigated the prodromal symptoms and suggested seven symptoms more likely to be present in prodrome of depression, namely sad mood, decreased interest in or pleasure from activities, difficulty concentrating, hopelessness, worrying/brooding, decreased self-esteem, and irritability. Mood instability is another symptom which is argued as a precursor of depressive episode and predictive factor.[6] Considering our results and literature, it appears that irritability and anxiety are more often found as prodromal symptoms. We could not find if the core symptoms of depression such as depressed mood and anhedonia can be a common prodromal presentation. Symptoms such as sleep difficulties and easy fatigability can be found more often than these core symptoms.

Multiple researchers suggested consistency of prodromal phase within individuals across prodromes in cases of depression.[18,19] There is also evidence to suggest that the residual symptoms in cases of depression can be similar to the prodromal symptoms. The clinical presentations of residual phase as well as prodromal phase are symptom wise similar in majority of patients with depression.[20] The findings of Manhert et al.[21] in cases of recurrent depressive disorder were in line with the suggestion of similarity between prodromal and residual symptoms of depression. The most common symptoms in residual and prodromal phases in our study were similar ones, especially the three most common symptoms in both phases were irritability, reduced energy, and insomnia. It can be very well argued that irritability is the only symptom which is not only most likely to be present but also most likely to be persistent in residual phase if it is present in prodromal phase.

Irritability was significantly associated with a positive family history of depression, whereas interrupted sleep, psychic tension, and stress with a negative family history in few but significant number of patients. Recent research inquiring the validity of diagnoses of 'adjustment disorder' and 'depressive disorder NOS' suggests patients of subthreshold depression with stressor (adjustment disorder) had more insomnia than those with depressive disorder NOS and less likely to be associated with positive family history of depression.[4] A team of Chinese investigators identify different factors of major depression apart from depressive symptom factors, namely vegetative symptoms, cognitive symptoms, and agitated symptoms factors, of which agitated factors are characterized by anxiety and irritability.[22] It can be argued that the irritability as a prodrome may be genetically determined, but irritability as a symptom in active depression may not be specific to genetic association. There is evidence to suggest that irritability in depression may be associated with atypical features, mixed state, and bipolar diathesis.[23] If irritability during prodrome suggests genetic loading for depression? It requires further research to draw such conclusion.

Depression is a complex and heterogeneous disorder clinically as well as etiologically. The heterogenicity of symptom expression suggests difference in the underlying characteristics and symptom reporting of depression.[24] Females are more likely to have psychosomatic subtype of depression with symptoms such as psychomotor disturbances and impaired concentration, whereas being male is associated with cognitive-emotional subtype.[25] We could find a few gender differences in prodromal symptoms. We observed females more likely to report fatigue, hypochondriasis, concentration difficulty, and distractibility during prodrome while males reporting psychic tension. These differences are understandable due to variety in clinical presentation of depressive disorder between genders and it is argued to have gender-specific diagnosis for stress-related disorders.[26] It is suggested that men tend to have aggression and substance use compared to women who tend to have irritability, sleep problems, stress, and anhedonia in depression.[27]

CONCLUSION

Prodromal symptoms may give a clue toward prediction of the clinical picture of depressive episode as well as its etiological identification. Prodrome is present in most cases of depression lasting from weeks to months but is heterogeneous in nature as with depressive disorder per se. The common symptoms in prodrome and depression are irritability, anxiety, sleep problems, and fatigability. Consistency between prodromal and residual phases could not be established except for irritability in our sample. Irritability is associated with positive family history of depression. Fatigability and impaired concentration associated with female gender. Irritability can be identified as a common prodromal symptom and associated with genetic loading of depression. Irritability is also likely to present as residual symptom if it is present in prodromal phase. Identification of prodrome of depression can help to plan early intervention in vulnerable population to minimize the disability associated in terms of duration as well as severity.

The limitation of our study is the cross-sectional study design and retrospective identification of prodrome. We interviewed patients when they had normal depression scores and used objective data to the possible extent to minimize the recall bias. Since we have only included the patients in full remission, we cannot generalize our result to the cases of depression who may not attend full remission or have significant residual anxiety symptoms.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Vihang N. Vahia (Professor emeritus) and Dr. Deoraj Sinha (Associate professor and Head), Department of Psychiatry, HBTMC and Dr. RN Cooper Municipal General Hospital, Mumbai, and

The patients who consented for the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJ, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matorin AA, Ruiz P. Clinical manifestation of psychiatric disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan & Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. New Delhi: Wolters Kluwer (India) Pvt. Ltd.; 2009. pp. 1071–107. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Dalrymple K, Chelminski I, Young D. “Subthreshold” depression: Is the distinction between depressive disorder not otherwise specified and adjustment disorder valid? J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:470–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fils JM, Penick EC, Nickel EJ, Othmer E, Desouza C, Gabrielli WF, et al. Minor versus major depression: A comparative clinical study. Primary care companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;12:PCC–08m00752. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08m00752blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marwaha S, Balbuena L, Winsper C, Bowen R. Mood instability as a precursor to depressive illness: A prospective and mediational analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:557–65. doi: 10.1177/0004867415579920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broome MR, He Z, Iftikhar M, Eyden J, Marwaha S. Neurobiological and behavioural studies of affective instability in clinical populations: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;51:243–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molnar G, Feeney MG, Fava GA. Duration and symptoms of bipolar prodromes. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:1576–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.12.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson A, Cavanagh J, Scott J. A systematic review of manic and depressive prodromes. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:209–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charan J, Biswas T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:121–6. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.116232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, et al. The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton M. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: APA; 2000. Hamilton rating scale for depression (Ham-D) pp. 526–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bech P. Clinical Interview for Depression and Related Syndromes (CIDRS) Copenhagen: Hillord; 2011. p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young MA, Grabler P. Rapidity of symptom onset in depression. Psychiatry Res. 1985;16:309–15. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(85)90122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fava GA, Grandi S, Canestrari R, Molnar G. Prodromal symptoms in primary major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 1990;19:149–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iacoviello BM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Choi JY. The early course of depression: A longitudinal investigation of prodromal symptoms and their relation to the symptomatic course of depressive episodes. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:459–67. doi: 10.1037/a0020114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keitner GI, Solomon DA, Ryan CE, Miller IW, Mallinger A, Kupfer DJ, et al. Prodromal and residual symptoms in bipolar I disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37:362–7. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith JA, Tarrier N. Prodromal symptoms in manic depressive psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27:245–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00788937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fava GA, Grandi S, Zielezny M, Canestrari R, Morphy MA. Cognitive behavioral treatment of residual symptoms in primary major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1295–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.9.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manhert F, Reicher H, Zalaudek K, Zapotoczky H. Prodromal and residual symptoms in recurrent depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1997;7:s159–60. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Aggen S, Shi S, Gao J, Li Y, Tao M, et al. The structure of the symptoms of major depression: Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in depressed Han Chinese women. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1391–401. doi: 10.1017/S003329171300192X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parneix M, Pericaud M, Clement JP. Irritability associated with major depressive episodes: Its relationship with mood disorders and temperament. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2014;25:106–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hybels CF, Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Steffens DC. Heterogeneity in symptom profiles among older adults diagnosed with major depression. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:906–22. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210002346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carragher N, Adamson G, Bunting B, McCann S. Subtypes of depression in a nationally representative sample. J Affect Disord. 2009;113:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter-Snell C, Hegadoren K. Stress disorders and gender: Implications for theory and research. Canadian J Nurs Res. 2003;35:34–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin LA, Neighbors HW, Griffith DM. The experience of symptoms of depression in men vs. women: Analysis of the national comorbidity survey replication. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1100–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]