Abstract

Objective

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and subclinical atherosclerosis, but the reasons for the excess risk are unclear. We explored whether psychosocial comorbidities, which may be associated with CVD in the general population, are differentially associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in RA compared to controls.

Methods

Data were from a longitudinal cohort study of 195 RA patients and 1,073 non-RA controls. Using validated scales, heterogeneity in the associations of psychosocial measures (depression, stress, anxiety/anger, support, discrimination/hassles) with measures of subclinical atherosclerosis (coronary artery calcium [CAC] and carotid intima-media thickness [IMT]/plaque) were compared in RA and non-RA groups using multivariable generalized linear models. Computed tomography and ultrasound were used to identify CAC and IMT/plaque, respectively. CAC >100 units was used to define moderate/severe CAC.

Results

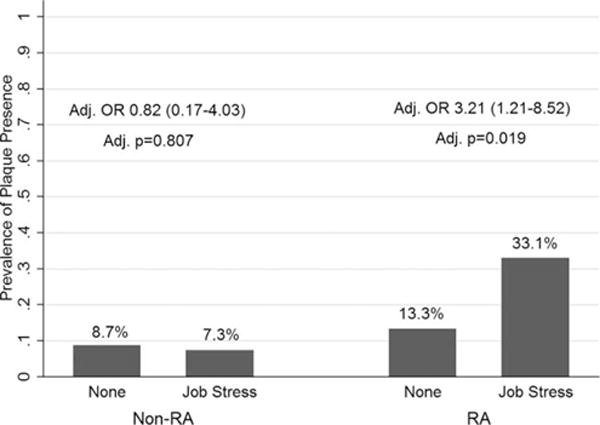

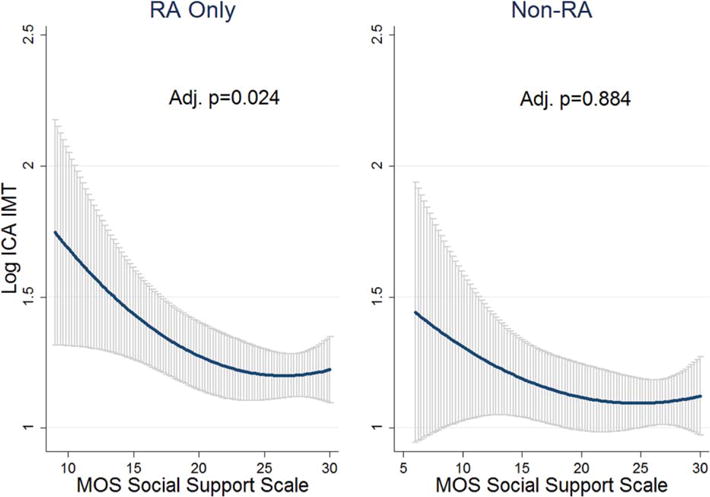

In RA, per-unit higher anxiety scores (odds ratio [OR] 1.10, P = 0.029), anger scores (OR 1.14, P = 0.037), depressive symptoms (OR 3.41, P = 0.032), and caregiver stress (OR 2.86, P = 0.014) were associated with increased odds of CAC >100 units after adjustment for relevant covariates. These findings persisted despite adjustment for markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 levels) and were seen only in RA, not in controls (adjusted multiplicative interaction P = 0.001–0.077). In RA, job stress was associated with an increased risk of carotid plaque (adjusted OR = 3.21, P = 0.019), and increasing social support was associated with lower internal carotid IMT (adjusted P = 0.024).

Conclusion

Depressive symptoms, stress, anger/anxiety, and social support may preferentially affect CVD risk in RA, and screening/treatment for psychosocial morbidities in RA may help ameliorate the additional CVD burden.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is more prevalent in those with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) than in the general population and accounts for much mortality (1,2). Previous studies have shown that those with RA have a higher burden of atherosclerosis than non-RA populations, and other measures of CVD risk, such as coronary artery calcium (CAC) and carotid intima-media thickness (IMT), may be good predictors of CVD events in RA (3,4). Chronically elevated levels of systemic inflammation are thought to be a major driver of risk (5), as traditional risk factors do not fully account for excess CVD in RA (6).

RA is also associated with a higher prevalence of psychosocial comorbidities compared to the general population (7,8). These diminish quality of life and contribute to disease severity and cost, as CVD and depression account for the largest share of RA health care costs (9,10). Depression, anxiety, and stress (measured using validated scales or International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] codes) have been associated with increased CVD risk and myocardial ischemia in the general population as well (11–13). In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I, depressive symptoms were associated with an almost 2-fold higher incidence of CVD (14). A recent study of US veterans showed that anxiety/panic disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder also conferred an increased risk of myocardial infarction (12). It has been hypothesized that these associations occur through an increased inflammatory response leading to increased vascular resistance, as well as other possible mechanisms, such as CVD-aggravating behaviors (15,16).

Although an association between depression (defined using ICD-9 codes) and increased incidence of myocardial infarction in RA has been reported (17), the association between more broadly defined psychosocial comorbidities and subclinical atherosclerosis in the context of traditional CVD risk factors and disease-related characteristics remains unexplored. To determine whether psychosocial comorbidities confer additional CVD risk in RA, we explored the differences between those with and without RA in the association of an array of psychosocial comorbidities (anger, anxiety, depression, stress, social support, discrimination, and hassles) with measures of subclinical atherosclerosis. We hypothesized that these psychosocial comorbidities would display more robust associations with atherosclerosis measures in RA patients than in controls.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Study population

Participants were enrolled in the Evaluation of Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease and Predictors of Events in Rheumatoid Arthritis (ESCAPE RA) study, a cohort study of the prevalence, progression, and risk factors for subclinical CVD in RA that has been described previously (3). Briefly, it was designed with inclusion and exclusion criteria identical (except for the diagnosis of RA) to those of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a population-based cohort study of subclinical CVD (18). ESCAPE RA inclusion criteria were 1) the fulfillment of the American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of RA of >6 months (19), and 2) being 45–84 years of age. Exclusion criteria were 1) having prior self-reported, physician-diagnosed myocardial infarction, heart failure, coronary artery revascularization, peripheral vascular (arterial) disease or procedures, an implanted pacemaker or defibrillator devices, and current atrial fibrillation, 2) weight exceeding 300 pounds, and 3) having had a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest within 6 months prior to enrollment (excluded to minimize radiation exposure). Thirteen controls were excluded for reporting having taken disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) typically used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. RA participants were recruited from the Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center and by referral between 2004 and 2006, with 195 having completed subclinical atherosclerosis data. Non-RA controls, recruited from 2000 to 2002, were derived from Baltimore MESA study participants (n = 1,073). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Subsequent analyses were approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Measurement of psychosocial comorbidities

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

The CES-D is a well-validated depression-screening scale with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.85 in the general population) that has also been found to correlate well with other depression scales, depressive symptoms, and life events (20). The 20 items on the scale are scored by summation of responses (range 0–60). Depressive symptoms were defined as a CES-D score >16.

Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI)

The STAI scale measures relatively stable individual differences in anxiety proneness, and internal consistency is high (median α = 0.90 across various populations) (21). The STAXI scale measures the intensity of anger as an emotional state and differences in anger proneness as a personality trait. It has a high internal consistency (α = 0.87 for both sexes) (21). For both scales, the 10 questions are scored by summation of responses, and scores range from 10 to 40.

Chronic Burden Scale

The Chronic Burden Scale measures ongoing stress in 5 domains: personal health stress, caregiver stress, relationship stress, job stress, and financial stress (22). For each domain, participants were asked to indicate whether they experienced ongoing stress (i.e., stress related to a “serious ongoing health problem in yourself,” a “serious ongoing health problem in someone close to you,” “ongoing difficulties with your job or ability to work,” “ongoing financial strain,” “ongoing difficulties in a relationship with someone close to you”) and, if yes, whether this stress persisted for 6 months or longer and whether the situation was almost never stressful (scored 1), sometimes stressful (scored 2), or often stressful (scored 3). Responses were recoded for analyses based on prior MESA studies (23,24) to contrast with those who reported that they were sometimes or often stressed in a given domain that persisted for at least 6 months (scored 1) with those who did not (scored 0). Total stress was the sum of all positive responses in each domain of stress and ranged from 0 to 5.

Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey (Modified)

The MOS Social Support Survey measures perceived support in multiple domains, including tangible, emotional, affective, and positive support (25). The short form, used in this study, has high internal consistency (α = 0.88) and correlated highly with measures of loneliness/companionship in field studies (26). The 6 questions were scored by summation, with scores ranging from 6 to 30.

Perceived Discrimination Scale and Everyday Hassles Scale (27–29)

The Perceived Discrimination Scale, based on the Major Experiences of Discrimination Abbreviated Test, scored the total number of affirmative responses to 6 questions about perceived discrimination in both the past year and over the lifetime (range 0–6). The Hassles Scale, based on the Everyday Discrimination Scale, was computed by the summation of scores for 9 items ranging from 1 to 6 (never to almost every day), with total scores ranging from 9 to 54. Total scores for all psychosocial scales were considered incomplete if any one question contained missing data, which resulted in completed tests, on average, for 98.6% of RA participants and 94.9% of controls.

Subclinical atherosclerosis: CAC and carotid IMT

All participants underwent cardiac multidetector row CT scanning using methodology described previously (30). CAC was quantified using the Agatston et al method (31), with a phantom of known calcium density scanned along with the participant to ensure standardization across scans (32). For this study, a cutoff of CAC >100 (moderate to severe coronary artery disease) (33) was chosen. Intraobserver agreement and interobserver agreement for CT assessors were high (κ = 0.93 and κ = 0.90, respectively) (3).

Carotid ultrasound imaging was performed on all RA participants and on a subset of age-, sex-, and race-matched MESA controls concurrently to ensure compatibility (n = 198) (34). Plaque was defined as per the Framingham study (35) as focal protrusion into the lumen of the internal carotid artery (ICA)/bulb with reduction in the lumen diameter of more than 25% (36). For ICA IMT measurements, intraobserver coefficient of variation was 6.93% and interobserver coefficient of variation was 18.8%. For common carotid artery (CCA) IMT measurements, intraobserver and interobserver coefficients of variation were 3.48% and 10.7%, respectively (36).

Measurement of covariates

The ESCAPE RA study used the same questionnaires, equipment, methods, and quality control procedures as MESA (18). Information on demographics, education, employment, income, smoking, and alcohol use was collected by questionnaire. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg (the average of the last 2 out of 3 resting, seated measurements), or taking antihypertensive medication. Diabetes mellitus was classified as treated diabetes mellitus (any fasting glucose and taking medication for diabetes mellitus), untreated diabetes mellitus (fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl and not taking medication), impaired fasting glucose (fasting glucose 100– 125 mg/dl and not taking medication), and normal (fasting glucose <100 mg/dl and not taking medication). Physical activity was defined based on prior MESA studies using total intentional activity (metabolic equivalent–hours/ week) and walking pace (where low = 0 to <2 mph, medium = 2 to <3 mph, and fast = 3 to 4 mph) (37). Laboratory values were measured as per the MESA protocol (18), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was estimated in plasma specimens having a triglyceride value <400 mg/dl using the Friedewald et al equation (38).

RA-specific covariates

In RA participants, 44 joints were examined by a single trained assessor for swelling, tenderness, deformity, and surgical replacement/fusion. RA disease duration was calculated based on self-report from the time of physician diagnosis. RA activity was calculated using the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C-reactive protein level (DAS28-CRP) (39). Functional limitation was assessed with the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (40). Any history of taking prednisone and biologic and nonbiologic DMARDs was ascertained in the interview. Single-view, anteroposterior radiographs of the hands and feet were obtained and scored using the Sharp/van der Heijde method (41) by a single trained radiologist blinded to participant characteristics. For 5 subjects with incomplete radiographic assessments, the missing score (hand or foot) was imputed from the available data based on a regression equation using data from the remaining subjects in the cohort. Both rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, with high seropositivity defined as ≥40 units/ml.

Statistical analysis

Various demographic CVD risk factors and psychosocial comorbidities were examined by RA status. Means 6 SDs for normally distributed variables and medians and interquartile ranges for non-normally distributed variables were calculated, with differences compared using t-tests. For categorical variables, counts and percentages were calculated and differences were compared using chi-square tests. Multivariable linear and logistic regression was performed to explore associations between psychosocial comorbidities and RA status, adjusting for relevant sociodemographic and CVD risk variables. Multivariable linear and logistic regression was performed between psychosocial comorbidities and CAC score, ICA/CCA IMT (logarithmically transformed) scores, CAC categorical variables, and plaque presence. Models were fit with common demographic and CVD risk variables, including age, sex, race, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, education, marital status, income, diabetes mellitus, alcohol use, employment status, smoking, physical activity/walking pace, cholesterol (high-density lipoprotein [HDL], LDL, triglycerides, and total cholesterol), as well as markers of RA activity (RA duration, total number of swollen/tender joints, total number of deformed/replaced joints, DAS28, HAQ score, Sharp/van der Heijde score, RF [>40], CCP [>40], and past/current use of DMARDs, biologic agents, and prednisone). An initial backward stepwise model was used to pare down the extensive list of potential confounders (exclusion P > 0.10 and inclusion P < 0.09). The variables identified through this process and others considered clinically relevant by expert opinion were assessed using likelihood-ratio testing designed to explore how each potential covariate changed the overall model (cutoff of P < 0.1) to create the final parsimonious models. All models were assessed for linearity/goodness of fit and, for linear regression models, normality of residuals. For a significant association between each psychosocial comorbidity and CVD outcome, the other psychosocial comorbidities were added into models to explore the independence of associations. In addition, for significant models, markers of inflammation (CRP and interleukin-6 [IL-6] levels) were also added into models. To minimize multiple comparisons, all models were initially fit in RA participants only, and if significant associations were found, the models were then fit in the overall and non-RA participants to assess interactions, both additive ([RA + Psych + RA&Psych] − RA − Psych + 1) and multiplicative (RA × psych). All analyses were conducted using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp). A 2-tailed α = 0.05 was used throughout.

RESULTS

Participant demographics

Compared with controls, those with RA were younger, more likely to be white, and more likely to be married. They also had, on average, lower BMIs, higher levels of education and income, and different rates of employment. They were significantly less likely to have diabetes mellitus or hypertension. There were differences in alcohol use but not in smoking. Those with RA had slightly higher average HDL, CRP, and IL-6 levels, but there were no significant differences in LDL, total cholesterol, or triglyceride levels. Although there were no differences in intentional exercise levels, they trended toward slower walking speeds (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of selected variables in RA and non-RA controls*

| Variable | RA (n = 195) |

No RA (n = 1,073) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD years | 59 ± 8.7 | 63 ± 10 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 118 (61) | 573 (53) | 0.067 |

| Race | |||

| White | 169 (87) | 524 (49) | < 0.001 |

| Nonwhite | 26 (13) | 549 (51) | |

| Education | |||

| Some high school or less | 7 (4) | 121 (11) | 0.015 |

| Completed high school | 41 (21) | 211 (20) | |

| Some college | 70 (36) | 323 (31) | |

| Bachelor’s | 40 (20) | 186 (18) | |

| Graduate school/professional | 37 (19) | 213 (20) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 159 (82) | 580 (56) | < 0.001 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 29 (15) | 378 (36) | |

| Never married | 7 (3) | 87 (8) | |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 101 (52) | 560 (53) | < 0.001 |

| Not employed | 46 (24) | 142 (14) | |

| Retired | 46 (24) | 353 (33) | |

| BMI, mean ± SD kg/m2 | 28.4 ± 5.3 | 29.4 ± 5.8 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| Normal | 151 (77) | 581 (55) | < 0.001 |

| Impaired | 33 (17) | 319 (30) | |

| Untreated | 1 (1) | 53 (5) | |

| Treated | 10 (5) | 110 (10) | |

| Hypertension | 58 (30) | 551 (51) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 80 (41) | 485 (46) | 0.135 |

| Former | 92 (47) | 418 (40) | |

| Current | 23 (12) | 152 (14) | |

| Alcohol | |||

| Never | 15 (8) | 155 (15) | 0.005 |

| Former | 72 (37) | 294 (28) | |

| Current | 107 (55) | 590 (57) | |

| Walking pace | |||

| Slow | 85 (44) | 368 (35) | 0.054 |

| Medium | 79 (40) | 473 (45) | |

| Fast | 31 (16) | 215 (20) | |

| LDL, mean ± SD mg/dl | 116 ± 31 | 117 ± 32 | 0.54 |

| HDL, mean ± SD mg/dl | 55 ± 19 | 52 ± 15 | 0.015 |

| Total cholesterol, mean ± SD mg/dl | 195 ± 38 | 192 ± 36 | 0.33 |

| Triglycerides, mean ± SD mg/dl | 126 ± 92 | 118 ± 72 | 0.17 |

| Intentional physical activity, mean ± SD MET-hours/week | 25.8 ± 33 | 29.8 ± 50 | 0.28 |

| CRP, mean ± SD mg/liter | 6.65 ± 12.3 | 4.24 ± 6.6 | 0.0001 |

| IL-6, mean ± SD mg/ml | 5.51 ± 5.0 | 1.65 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

Values are the number (percentage) unless indicated otherwise. RA = rheumatoid arthritis; BMI = body mass index; LDL= low-density lipoprotein; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; MET = metabolic equivalent; CRP = C-reactive protein; IL-6 = interleukin-6.

Among the characteristics specific to the RA group (previously reported and not shown) (3), median RA duration was 9 years. The majority had high seropositivity for RF (65%) and anti-CCP (71%). The mean DAS28 score was 3.65, reflecting low to moderate disease activity. Seventy-four percent had taken or were currently taking prednisone, and 94% (n = 184) were currently taking a DMARD. They had been exposed to mean ± SD 3.1 ± 1.7 DMARDs and mean ± SD 0.7 ± 0.7 biologic agents.

Psychosocial variables according to RA status

After adjustment for demographic variables (age, sex, race, BMI, education, marital status, income, employment, alcohol use, smoking, and walking pace), RA was associated with higher CES-D scores/frequency of depressive symptoms, levels of personal health stress, and job stress, and lower levels of relationship stress, with a trend toward less financial stress. RA was not significantly associated with caregiver stress. After adjustment, RA participants had less anger, but there were no significant differences in anxiety or social support levels, and there was a trend toward lower discrimination/hassles scores and higher total stress (Table 2).

Table 2.

Psychosocial measures by RA status: adjusted prevalence percentages*

| RA adjusted prevalence | No-RA adjusted prevalence | Adjusted P† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical variables, % | |||

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥16) | 12.7 | 6.4 | 0.012 |

| Personal health stress | 42.5 | 12.3 | < 0.001 |

| Caregiver stress | 29.7 | 31.8 | 0.614 |

| Job stress | 12.0 | 7.2 | 0.031 |

| Financial stress | 10.8 | 16.8 | 0.051 |

| Relationship stress | 11.7 | 18.5 | 0.023 |

| Continuous variables, mean ± SD | |||

| Anger score | 13.83 ± 3.5 | 14.69 ± 3.3 | 0.003 |

| Anxiety score | 15.22 ± 4.5 | 15.78 ± 4.1 | 0.126 |

| Social support (MOS) | 24.63 ± 5.2 | 24.59 ± 4.9 | 0.926 |

| Discrimination score | 0.63 ± 1.0 | 0.76 ± 0.97 | 0.102 |

| Hassles score | 14.2 ± 6.1 | 15.1 ± 5.7 | 0.08 |

| CES-D score | 7.85 ± 6.8 | 6.65 ± 6.4 | 0.033 |

| Total stress | 1.14 ± 1.2 | 0.98 ± 1.1 | 0.11 |

RA = rheumatoid arthritis; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; MOS = Medical Outcomes Study.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, education, marital status, income, employment, alcohol use, smoking, and walking pace based on the categories used in Table 1. P values are based on multivariable logistic regression models.

Association of psychosocial variables with subclinical atherosclerosis: RA versus control

In RA, each 1-unit higher anxiety score was associated with a 10% increase in the odds of having CAC >100 units (P = 0.029) after adjustments for age, sex, smoking, RA duration, and past/current prednisone use. These associations were seen only in the RA group, with adjusted multiplicative interaction term P = 0.001 and additive interaction term P < 0.001 (Table 3). When adding other psychosocial variables into adjusted models of anxiety and CAC >100 units, job stress (P = 0.077) was a potential covariate but did not remove overall significance (P = 0.005). Anxiety and job stress were correlated (correlation coefficient of 0.43, P < 0.001), and in RA, those with job stress scored, on average, 4.8 points higher on the anxiety scale (P < 0.001; data not shown).

Table 3.

Adjusted associations of psychosocial variables with CAC: RA versus non-RA and the effect of markers of inflammation*

| Outcome CAC >100 | RA

|

Controls

|

Interaction testing

|

Adding inflammation markers

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj OR (95% CI) | P | Adj OR (95% CI) | P | Multi-plicative/Additive P† | New adj OR (95% CI)‡ | P | IL-6, P | New adj OR (95% CI)§ | P | CRP, P | |

| Anxiety | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 0.029 | 0.93 (0.90–0.97) | 0.001 | 0.001/< 0.001 | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 0.028 | 0.657 | 1.11 (1.01–1.21) | 0.025 | 0.468 |

| Anger | 1.14 (1.01–1.29) | 0.037 | 1.00 (0.95–1.04) | 0.87 | 0.051/0.013 | 1.14 (1.01–1.30) | 0.037 | 0.722 | 1.14 (1.01–1.29) | 0.038 | 0.627 |

| CES-D | 1.05 (0.99–1.10) | 0.059 | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.222 | 0.012/0.001 | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 0.055 | 0.611 | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) | 0.043 | 0.336 |

| CES-D ≥16 vs. <16 units | 3.41 (1.11–10.5) | 0.032 | 0.83 (0.45–1.52) | 0.547 | 0.027/0.135 | 3.54 (1.14–11.0) | 0.028 | 0.456 | 3.69 (1.18–11.6) | 0.025 | 0.329 |

| Caregiver stress vs. none | 2.86 (1.23–6.66) | 0.014 | 1.03 (0.73–1.45) | 0.857 | 0.077/0.107 | 2.79 (1.19–6.50) | 0.018 | 0.623 | 2.84 (1.22–6.62) | 0.015 | 0.551 |

Odds ratios represent the average unit change in the frequency of CAC >100 units per 1-unit higher psychosocial variable score. RA models adjusted for age, sex, smoking, RA duration, and past/current prednisone use. Models of categorical depression and caregiver stress additionally adjusted for body mass index. Control models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, hypertension, and smoking. CAC = coronary artery calcium; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; Adj = adjusted; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; IL-6 = interleukin-6; CRP = C-reactive protein; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

P values represent adjusted multiplicative (RA × psychosocial variable interaction terms) or additive interaction terms. ([RA + Psych + RA&Psych] − RA − Psych + 1) adjusted for age, sex, race, hypertension, body mass index, and smoking.

New adjusted OR after adding IL-6 (continuous) into overall adjusted models of psychosocial variables and CAC >100.

New adjusted OR after adding CRP (continuous) into overall adjusted models of psychosocial variables and CAC >100.

Each 1-unit higher anger score was associated with a 14% increase in the odds of CAC >100 units (P = 0.037), after adjustment for the previously listed covariates. This was observed in RA participants only (adjusted multiplicative interaction term P = 0.051, additive interaction term P = 0.013) (Table 3). When adding other psychosocial comorbidities into adjusted models of anger and CAC >100 units, the combination of job stress and anxiety significantly affected the overall model but only anxiety removed overall significance on its own (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adjusted models of anger, depression, and caregiver stress with CAC >100: addition of job stress and anxiety*

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anger, per unit | 1.14 (0.037) | 1.16 (0.025) | 1.10 (0.162) | 1.11 (0.157) |

| Job stress | 0.60 (0.322) | 0.34 (0.065) | ||

| Anxiety, per unit | 1.07 (0.152) | 1.13 (0.027) | ||

| CES-D ≥16 | 3.41 (0.032) | 6.02 (0.006) | 1.86 (0.393) | 2.86 (0.201) |

| Job stress | 0.41 (0.119) | 0.21 (0.019) | ||

| Anxiety, per unit | 1.10 (0.114) | 1.17 (0.028) | ||

| Caregiver stress | 2.86 (0.014) | 2.81 (0.016) | 2.33 (0.058) | 2.16 (0.088) |

| Job stress | 0.73 (0.544) | 0.32 (0.067) | ||

| Anxiety, per unit | 1.11 (0.035) | 1.17 (0.006) |

Values are the odds ratios (P values). Model 1 represents logistic regression models of either per unit anger or CES-D ≥16 or caregiver stress with CAC >100, adjusted for age, sex, smoking, body mass index, past/current prednisone use, and rheumatoid arthritis duration. Anger models were not adjusted for body mass index. Model 2 represents Model 1 with the addition of job stress as a covariate. Model 3 represents Model 1 with the addition of anxiety as a covariate. Model 4 represents Model 1 with the addition of both job stress and anxiety as covariates. CAC = coronary artery calcium; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

For depression, in RA participants, a 1-unit higher CES-D score was associated with a 5% increase in the odds of CAC >100 units with borderline significance (P = 0.059) after adjustment for covariates. These associations were seen only in RA participants, with an adjusted multiplicative interaction term of P = 0.012 and an additive interaction term of P = 0.001. The presence of depressive symptoms (CES-D >16) was associated with a >3-fold increase in the odds of CAC >100 units (P = 0.032) after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, smoking, RA duration, and past/current prednisone use. Again, this was observed only in RA participants, with an adjusted multiplicative interaction of P = 0.027 and an additive interaction of P = 0.135 (Table 3). When adding other psychosocial comorbidities into adjusted models of depressive symptoms and CAC >100 units, the combination of job stress and anxiety significantly affected the overall model but only anxiety removed overall significance on its own (Table 4).

Caregiver stress was associated with a >2-fold increase in the odds of CAC >100 units (P = 0.014) after adjustment for the previously listed covariates. This was only seen in RA participants, not controls, with an adjusted multiplicative interaction term of P = 0.077 and an additive interaction of P = 0.107 (Table 3). Although job stress alone did not remove significance from the model, adding anxiety into models gave the overall association a borderline P value (Table 4). All of the previously detailed models (logistic regression) met assumptions for linearity and goodness of fit.

When adding CRP and IL-6 levels into these overall adjusted models of anxiety, anger, depression, and caregiver stress with CAC >100 units, neither of them were significant covariates nor removed overall significance, suggesting that CRP and IL-6 do not influence the association of psychosocial variables with CAC >100 (Table 3). There were no other significant associations between any other psychosocial comorbidities and CAC (data not shown).

Occupational stress and carotid plaque: RA versus control group

In RA, having job stress was associated with >3-fold increased odds of carotid artery plaque presence (P = 0.019) after adjustment for covariates (Figure 1). These logistic regression models met assumptions for linearity and goodness of fit. After adding other psychosocial variables into RA-specific models of job stress and plaque presence with all covariates, caregiver stress was a significant covariate (P = 0.045) but did not remove overall significance (P = 0.009). This association was not seen in controls; however, the adjusted multiplicative interaction term P value was 0.210 and the additive interaction P value was 0.142. Neither the addition of IL-6 nor that of CRP changed the estimates in this model. There were no other significant associations between any other psychosocial comorbidity and plaque (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Adjusted carotid plaque presence by job stress in those with RA compared with non-RA controls. In the RA group, job stress confers increased risk for carotid plaque presence (odds ratio [OR] 3.21 [95% confidence interval 1.21–8.25], adjusted P = 0.019, adjusted multiplicative interaction P = 0.210, and additive interaction P = 0.142). RA models adjusted for age, hypertension, education, and rheumatoid factor ≥40. Control models adjusted for hypertension and education. Adjusted multiplicative interaction P = 0.210 and adjusted additive interaction P = 0.142. Interaction models adjusted for education and hypertension. RA = rheumatoid arthritis.

Social support and carotid IMT: RA versus control group

Higher levels of social support were associated with lower ICA IMT levels (logarithmically transformed variable) in RA participants (P = 0.024) after adjustment for covariates (Figure 2). This association was more pronounced at lower levels of social support, as evidenced by the steeper curve of fit. Linear regression models met assumptions for linearity and normality by Shapiro-Wilk testing. Although this association was only seen in those with RA, there was no significant interaction (adjusted multiplicative interaction term P = 0.206, additive interaction P = 0.236). None of the other psychosocial variables were significant covariates in RA-only models, and the addition of IL-6 and CRP did not influence the model. There were no other significant associations between any other psychosocial comorbidity and carotid IMT (data not shown).

Figure 2.

The association between ICA IMT (logarithmically transformed scores) with the social support scale using line of fit and 95% confidence intervals in gray. In the RA group, as social support increases, log ICA IMT decreases. Adjusted P = 0.024, adjusted multiplicative interaction P = 0.206, and additive interaction P = 0.236. All models adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, education, low-density lipoprotein, and total cholesterol, and RA models adjusted additionally for past/current prednisone use and rheumatoid factor ≥40. Adjusted multiplicative interaction P = 0.206 and adjusted additive interaction P = 0.236. Interaction models adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, low-density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, and education. RA = rheumatoid arthritis; ICA = internal carotid artery; IMT = intima-media thickness; MOS = Medical Outcomes Study.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the associations between a wide range of psychosocial comorbidities and subclinical atherosclerosis in RA. We observed that RA was associated with higher levels of personal health stress and job stress as well as more prevalent depressive symptoms. In RA, anxiety, anger, depressive symptoms, and caregiver stress were associated with a high CAC score, reflecting moderate to severe coronary artery disease, even after adjustment for covariates. Additionally, higher levels of social support were associated with lower ICA IMT levels, and job stress was associated with an increased risk of carotid artery plaque presence in the RA group. Markers of inflammation, such as CRP and IL-6 levels, did not seem to influence these associations.

RA has been associated with both an increased prevalence of psychosocial morbidities and an increased risk of CVD compared to non-RA populations; moreover, both psychosocial comorbidities and CVD contribute significantly to mortality and cost in RA (2,7,9,42). Treharne et al found that in RA, those with CVD had higher rates of depressive symptoms (43). In 15,634 veterans with RA followed for 6 years, Scherrer et al found that depressed participants were 1.4 times more likely to have a myocardial infarction (17).

Our study found that RA participants had higher levels of several nondepression psychosocial comorbidities, such as stress, anger/anxiety, and low social support, and that these, along with depressive symptoms, may be associated with subclinical measures of atherosclerosis, potentially conferring increased risk for CVD. Interestingly, anger, depression, and anxiety were correlated, and the associations between anger/depression and CAC may be in part influenced by anxiety. Additionally, job stress also seemed to be a significant contributor to models exploring the effect of anxiety on CAC in RA, suggesting that the effect of the disease on functional status may be a significant driver of anxiety and may influence CVD risk. Social support was found to be negatively associated with carotid thickening in RA participants only, despite no differences in levels of social support between the 2 groups. Although some have postulated that physical activity plays a role in psychosocial comorbidities (44), our study found that neither intentional exercise nor walking pace were confounders in the associations we found between psychosocial comorbidities and markers of subclinical atherosclerosis. Our study, along with a prior MESA study (23), found no association between psychosocial comorbidities and subclinical atherosclerosis in controls, which may be due to limitations in the assessment of all facets of psychosocial comorbidities and subclinical atherosclerosis and its association with CVD.

A mechanistic theory implicates chronic systemic inflammation, common in autoimmune diseases, leading to accelerated atherogenesis, endothelial damage/dysfunction, abnormal myocardial perfusion, and increased risk of ischemia (1,5). In addition, studies have shown that depression and anxiety are associated with activation of the inflammatory cascade, cytokine release, and oxidative stress, leading to increased atherosclerosis (15,45). Veldhuijzen van Zanten et al found that in RA, those with high inflammation levels (CRP level >8 mg/liter) had increased systemic vascular resistance, heart rate, and mean arterial pressure during stress-inducing tasks (16). Although our study did not demonstrate that CRP or IL-6 levels influenced associations between psychosocial comorbidities and markers of subclinical atherosclerosis, there may be other inflammatory markers/pathways involved in the mechanism of these associations that need to be evaluated. A systematic review has also found that mental stress is associated with transient myocardial ischemia and decreased myocardial perfusion (13). This has clinical implications, in that screening and treatment of psychosocial comorbidities may be important not only in improving quality of life but also in reducing increased CVD risk in RA.

Limitations of this study include the possibility of cross-sectional biases, such as survival bias and the impossibility of establishing temporality/causality. Also, residual confounding is always a possibility, as it is impossible to fully assess/account for every variable potentially involved in these associations; however, a large number of potential confounders were assessed. Other limitations include the modest sample size of RA participants and the limited geographical generalizability. The strengths of this study include the wide range of sociodemographic and RA-specific variables, traditional CVD risk factors, and psychosocial comorbidities assessed, as well as the use of robust, well-validated scales. In addition, multiple measures of subclinical atherosclerosis were used in a standardized fashion with stringent quality control methods. Future studies are needed in larger populations to better characterize these associations and explore methods of screening for and treating psychosocial morbidities in the prevention of CVD in RA.

In conclusion, CVD and psychosocial risk factors account for much of the morbidity, mortality, and costs in RA, and screening and treatment for both is essential in the care of RA patients. Depression, stress, anxiety, anger, and social support may be associated with subclinical markers of atherosclerosis, which are robust predictors of CVD risk in RA and may confer additional risk for CVD.

Significance & Innovations.

Many studies have shown that rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is associated with an increased risk of both cardiovascular disease (CVD) and a wide range of psychosocial comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, and stress. In the general population, these psychosocial comorbidities may themselves be associated with increased CVD risk. To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the association between a wide range of psychosocial comorbidities and subclinical atherosclerosis in RA.

Anger, anxiety, depressive symptoms, certain types of stress, and low social support were associated with markers of subclinical atherosclerosis, including increased coronary artery calcium, carotid intima-media thickness, and plaque presence, even after adjustment for sociodemographic variables, CVD risk factors, and markers of RA disease activity/treatment and inflammation. This suggests that treating these psychosocial comorbidities may not only affect morbidity in RA but also ameliorate the increased mortality from CVD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center General Clinical Research Center and staff, the field center of the Baltimore MESA cohort, and the MESA Coordinating Center at the University of Washington, Seattle. They also thank the ESCAPE RA staff (Marilyn Towns, Michelle Jones, Patricia Jones, Marissa Hildebrandt, Shawn Franckowiak, and Brandy Miles) and the participants of the ESCAPE RA study who graciously agreed to take part in this research.

Dr. Bathon’s work was supported by the NIH (AR050026-01). Drs. Liu and Giles’ work was supported by a grant from the Rheumatology Research Foundation.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication. Dr. Giles had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Liu, Szklo, Bathon, Giles.

Acquisition of data. Liu, Bathon, Giles.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Liu, Szklo, Davidson, Bathon, Giles.

References

- 1.Hollan I, Meroni PL, Ahearn JM, Cohen Tervaert JW, Curran S, Goodyear CS, et al. Cardiovascular disease in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:1004–15. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe F, Mitchell DM, Sibley JT, Fries JF, Bloch DA, Williams CA, et al. The mortality of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:481–94. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giles JT, Szklo M, Post W, Petri M, Blumenthal RS, Lam G, et al. Coronary arterial calcification in rheumatoid arthritis: comparison with the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R36. doi: 10.1186/ar2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Llorca J, Martin J, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Carotid intima-media thickness predicts the development of cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;38:366–71. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ku IA, Imboden JB, Hsue PY, Ganz P. Rheumatoid arthritis: model of systemic inflammation driving atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2009;73:977–85. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Rincon I, Williams K, Stern MP, Freeman GL, Escalante A. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2737–45. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2737::AID-ART460>3.0.CO;2-%23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickens C, McGowan L, Clark-Carter D, Creed F. Depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:52–60. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pincus T, Griffith J, Pearce S, Isenberg D. Prevalence of self-reported depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:879–83. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.9.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joyce AT, Smith P, Khandker R, Melin JM, Singh A. Hidden cost of rheumatoid arthritis (RA): estimating cost of comor-bid cardiovascular disease and depression among patients with RA. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:743–52. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanecki K, Tyszko P, Wislowska M, Lyczkowska-Piotrowska J. Preliminary report on a study of health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:429–34. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2421-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan AZ, Strine TW, Jiles R, Mokdad AH. Depression and anxiety associated with cardiovascular disease among persons aged 45 years and older in 38 states of the United States, 2006. Prev Med. 2008;46:445–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scherrer JF, Chrusciel T, Zeringue A, Garfield LD, Hauptman PJ, Lustman PJ, et al. Anxiety disorders increase risk for incident myocardial infarction in depressed and nondepressed Veterans Administration patients. Am Heart J. 2010;159:772–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strike PC, Steptoe A. Systematic review of mental stress– induced myocardial ischaemia. European Heart J. 2003;24:690–703. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00615-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferketich AK, Schwartzbaum JA, Frid DJ, Moeschberger ML. Depression as an antecedent to heart disease among women and men in the NHANES I study: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1261–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.9.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skala JA, Freedland KE, Carney RM. Coronary heart disease and depression: a review of recent mechanistic research. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:738–45. doi: 10.1177/070674370605101203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJ, Kitas GD, Carroll D, Ring C. Increase in systemic vascular resistance during acute mental stress in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with high-grade systemic inflammation. Biol Psych. 2008;77:106–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scherrer JF, Virgo KS, Zeringue A, Bucholz KK, Jacob T, Johnson RG, et al. Depression increases risk of incident myocardial infarction among Veterans Administration patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:353–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–81. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, Marsh BJ. Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI) In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. 2nd. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. pp. 993–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bromberger JT, Matthews KA. A longitudinal study of the effects of pessimism, trait anxiety, and life stress on depressive symptoms in middle-aged women. Psychol Aging. 1996;11:207–13. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diez Roux AV, Ranjit N, Powell L, Jackson S, Lewis TT, Shea S, et al. Psychosocial factors and coronary calcium in adults without clinical cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:822–31. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-11-200606060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shivpuri S, Gallo LC, Crouse JR, Allison MA. The association between chronic stress type and C-reactive protein in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: does sex make a difference? J Behav Med. 2012;35:74–85. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1576–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor TR, Kamarck TW, Shiffman S. Validation of the Detroit Area Study Discrimination Scale in a community sample of older African American adults: the Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project. Int J Behav Med. 2004;11:88–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1102_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Williams S, Mohammed SA, Moomal H, Stein DJ. Perceived discrimination, race and health in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:441–52. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, McNitt-Gray M, Arad Y, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson JC, Kronmal RA, Carr JJ, McNitt-Gray MF, Wong ND, Loria CM, et al. Measuring coronary calcium on CT images adjusted for attenuation differences. Radiology. 2005;235:403–14. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2352040515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Budoff MJ, Nasir K, McClelland RL, Detrano R, Wong N, Blumenthal RS, et al. Coronary calcium predicts events better with absolute calcium scores than age-sex-race/ethnicity percentiles: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi H, Giles JT, Polak JF, Blumenthal RS, Leffell MS, Szklo M, et al. Increased prevalence of carotid artery atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis is artery-specific. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:730–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson PW, Hoeg JM, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Belanger AM, Poehlmann H, et al. Cumulative effects of high cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, and cigarette smoking on carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:516–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708213370802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bui AL, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, de Boer IH, Fried LF, Polak JF, et al. Cystatin C and carotid intima-media thickness in asymptomatic adults: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:389–98. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertoni AG, Whitt-Glover MC, Chung H, Le KY, Barr RG, Mahesh M, et al. The association between physical activity and subclinical atherosclerosis the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:444–54. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prevoo ML, van ’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight–joint counts: development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–48. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolfe F, Kleinheksel SM, Cathey MA, Hawley DJ, Spitz PW, Fries JF. The clinical value of the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire Functional Disability Index in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1480–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van der Heijde D. How to read radiographs according to the Sharp/van der Heijde method. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:261–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Li T, Katz RS. Chronic conditions and health problems in rheumatic diseases: comparisons with rheumatoid arthritis, noninflammatory rheumatic disorders, systemic lupus erythematosus, and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:305–15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Treharne GJ, Hale ED, Lyons AC, Booth DA, Banks MJ, Erb N, et al. Cardiovascular disease and psychological morbidity among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:241–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelley GA, Kelley KS. Effects of exercise on depressive symptoms in adults with arthritis and other rheumatic disease: a systematic review of meta-analyses. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maes M, Ruckoanich P, Chang YS, Mahanonda N, Berk M. Multiple aberrations in shared inflammatory and oxidative & nitrosative stress (IO&NS) pathways explain the co-association of depression and cardiovascular disorder (CVD), and the increased risk for CVD and due mortality in depressed patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psych. 2011;35:769–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]