To the Editor:

The circadian timing system aligns genetic, physiologic, and behavioral rhythms to solar time (1). The master pacemaker of the body is normally synchronized, or entrained, to solar time each day by environmental zeitgebers (“time givers”), particularly the light–dark cycle (2). When sleep is mistimed in relation to the endogenous circadian rhythm, the circadian regulation of the human transcriptome is disrupted (3) and health is adversely affected (4, 5).

Critically ill patients exhibit profound disruptions of circadian rhythmicity, most commonly in the form of a phase delay (6–8). The ICU environment has been implicated in the pathogenesis of these dysrhythmias, but evidence for this hypothesis has been lacking. Indirect support for this hypothesis derives from data showing that the light–dark cycle of a typical ICU is consistently weak and phase-delayed relative to the solar cycle (9). To more directly test this hypothesis, we conducted a randomized controlled pilot study in critically ill patients (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01284140) to determine the effect of timed light exposure (TLE) on the timing and amplitude of the 24-h 6-sulfatoxymelatonin (aMT6s) rhythm. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (10).

Methods

We enrolled adult (≥18 yr old) patients being treated in the medical ICUs at the University of Iowa and the University of Chicago for shock and/or respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Exclusion criteria included recent major surgery or general anesthesia, neuromuscular blockers, oliguria (<500 ml/d), major sensory impairments, acute neurologic disease, shift work, narcolepsy, drug overdose, and known bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder. The universities’ institutional review boards approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from participants or their authorized representatives.

Patients were randomly assigned to 48 hours of usual care or TLE. The intervention began the next morning, on Day 1, and enforced a specific period of enhanced light exposure from 9:00 a.m. to noon. The initial target of 5,000 lux (n = 10) administered by light box (Sunsation; SunBox Co.) was reduced to 400–700 lux (n = 14) to simplify administration, given evidence that the effects of light intensity on phase resetting are nonlinear and enhanced by prior dim light exposure (2, 11). All subjects receiving mechanical ventilation were ventilated in the assist-control mode at night and received targeted sedation according to institutional protocol (12).

We used the 24-hour profile of urinary aMT6s to assess circadian phase and amplitude (6, 13). Urine samples were collected hourly for 24 hours beginning at 8 a.m. on Day 1. This sampling procedure was repeated on the morning of Day 3, yielding two separate 24-hour profiles for each subject. For each 24-hour profile, total daytime (07:00–23:00) and nighttime (23:00–07:00) aMT6s excretion was determined by calculating the area under the curve for the interval.

The primary outcome measures were the change in timing of the acrophase (fitted maximum) of normalized aMT6s excretion between Day 1 and Day 3 in each group. Nonlinear regression using the least-squares approach (Prism 7; GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used to fit a single 24-hour cosine curve to all normalized data in each group on each day. Model parameters of acrophase and amplitude and their SEs were derived from these curves.

Between-group differences in baseline characteristics and ambient light exposure were tested using a t test or Mann-Whitney U rank sum test, as appropriate. Linear regression was used to examine the relationship between total aMT6s excretion and subject characteristics. Differences in proportions between the two groups were tested using Fisher’s exact test. An unpaired t test was used to compare best-fit values of rhythm amplitude between groups. ANOVA with repeated measures was used to examine the effect of treatment group and time on individual rhythm amplitude. Data were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the subjects. At baseline, the circadian rhythm of the cohort (n = 21) was phase delayed, with the best-fit acrophase occurring at 8:30 a.m. compared with between midnight and 5:00 a.m. in healthy adults (6).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| All* (n = 22) |

Paired Specimens (n = 11) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual Care (n = 11) | Timed Light (n = 11) | Usual Care (n = 5) | Timed Light (n = 6) | |

| Age, yr | 59.2 ± 9.5 | 64.6 ± 10.7 | 59.6 ± 7.7 | 67.2 ± 10.4 |

| Female, n (%) | 7 (63.6) | 5 (45.5) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| APACHE II score*† | 21.1 ± 4.9 | 23.3 ± 7.4 | 24.4 ± 2.0 | 25.5 ± 2.5 |

| Mechanically ventilated, n (%)‡ | 10 (90.9) | 10 (90.9) | 5 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Sepsis or systemic inflammatory response syndrome, n (%)‡ | 9 (81.8) | 9 (81.8) | 4 (80.0) | 4 (66.7) |

| Total urinary aMT6s excretion on Day 1, μg | 15.3 ± 15.4 | 15.0 ± 9.7 | 20.4 ± 8.1 | 14.5 ± 4.7 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2§ | 39.6 (27.4 to 46.7) | 26.0 (23.0 to 28.0) | 27.4 (26.0 to 37.9) | 25.0 (21.8 to 33.2) |

| Average peak creatinine during study period | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.6 |

| Baseline Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale | −2 (−4 to 0) | −2 (−4 to −1) | −4 (−4.5 to −1.5) | −2.5 (−4.3 to −1) |

| Sedative/analgesic infusions, n (%)‡ | ||||

| Propofol | 6 (54.5) | 8 (72.7) | 4 (80) | 6 (100) |

| Opioids | 7 (63.6) | 9 (81.8) | 5 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Benzodiazepines | 5 (45.5) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) |

| Dexmedetomidine | 3 (27.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) |

| ICU length of stay, d | 6.7 (4.3 to 16.4) | 8.9 (7.2 to 11.7) | 16.4 (10.7 to 22.9) | 11.1 (8.4 to 16.3) |

| Died in hospital, n (%) | 2 (18.2)|| | 4 (36.4)¶ | 2 (40.0)|| | 4 (66.7)¶ |

Definition of abbreviation: aMT6s = 6-sulfatoxymelatonin.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are reported as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range).

Twenty-four subjects were enrolled. Two subjects were withdrawn for clinical reasons before any study-related procedures. One subject’s baseline profile was unevaluable because of missing samples.

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score (15).

During the study period (16).

P = 0.002 for differences between the two groups (P = 0.25 for the subgroups with paired specimens).

One patient had received a stem cell transplant for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and died of complications related to multiple infections. The other patient had myelodysplastic syndrome and died of sepsis and multiple organ failure.

Air embolism (1), stage IV cancer (1), acute respiratory distress syndrome in the setting of T-cell lymphoma (1), and multiple myeloma with multiple complications (1).

Eleven subjects had evaluable profiles from both days. Of the remainder, 1 subject had missing overnight specimens, whereas the others had been discharged from the ICU, died, or had their urinary catheter removed. These patients were sicker than patients who did not have both profiles (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II 25 ± 5.3 vs. 19.4 ± 6.1; P = 0.03). TLE and usual care subjects had similar baseline characteristics and sedation regimens (Table 1), night/day ratio of aMT6s on Day 1 (P = 0.4), and days receiving mechanical ventilation while on study (P = 0.4).

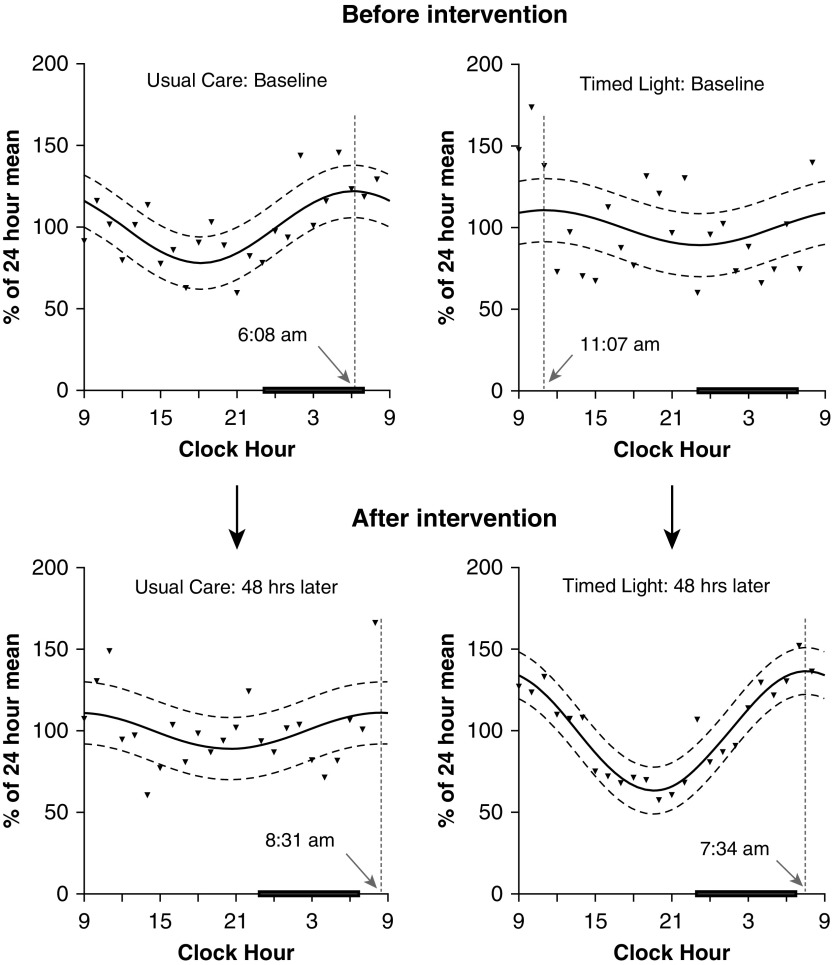

Both groups were phase delayed at baseline (Figure 1) (14). Patients who received usual care (n = 5) experienced an additional 2.4-hour delay from Day 1 to Day 3, although there was no statistically significant difference between the best-fit curves from these 2 days (P = 0.37). In contrast, circadian timing advanced by 3.6 hours (P = 0.0074) in patients who received TLE (n = 6, 5 of whom were treated with 5,000 lux). The proportion of patients with normal timing (acrophase occurring between midnight and 5:00 a.m.) on Day 3 did not differ between groups (1/5 subjects usual care vs 3/6 subjects TLE; P = 0.55). The circadian rhythm of the single subject who received the lower-dose light exhibited a phase advance from 11:17 a.m. to 4:05 a.m., along with an increase in rhythm amplitude (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effect of timed light exposure on circadian timing. Best-fit curves (solid lines) are shown for groups of subjects with paired collections from Day 1 and Day 3 (n = 6, timed light exposure; n = 5, usual care). Triangles are mean values for each hour; dashed curved lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Dotted vertical lines and arrows indicate timing of the acrophase. The black bars represent usual sleep time (23:00–07:00). Usual care is associated with a 2.4-hour worsening phase delay from Day 1 to Day 3. In contrast, circadian timing improves via a 3.6-hour phase advance after timed light. Narrower confidence intervals and increased amplitude of the best-fit curve after timed light are consistent with an increase in interindividual synchronization from entrainment. Using the extra sum-of-squares F test, the null hypothesis that model parameters of amplitude and phase were the same on Day 1 and Day 3 was tested for each group. This hypothesis was not rejected for patients who received usual care (P = 0.37). In contrast, for subjects who received timed light exposure, this analysis provided support for a more complex model in which the best-fit values for amplitude and phase were different on Day 1 and Day 3 (P = 0.0074), consistent with changes in circadian timing (phase advance) and amplitude (increase).

The amplitude of the best-fit curve on Day 3 was greater with TLE than with usual care (36.6 ± 14.5% vs. 11.0 ± 17.7%; P = 0.03). In contrast, there was no effect of treatment group, time, or their interaction on the mean amplitude of individually fitted curves from Day 3 (P ≥ 0.36). Taken together, these results are consistent with increased interindividual synchronization of the aMT6s rhythm with TLE.

Discussion

This pilot study confirms our previous finding (6): The circadian rhythms of critically ill patients are typically phase delayed. In addition, our results suggest that appropriately timed light therapy entrains the circadian rhythms of critically ill patients, resulting in improved synchronization and earlier timing.

This pilot study demonstrates the feasibility of a nonpharmacologic approach to improve circadian timing and amplitude in the critically ill. Enrollment was straightforward and the protocol was both easy to administer and well tolerated. Specimen collection was also highly successful in this complex environment, with 91.7% (770/840) of all planned specimen collections successfully completed. This approach allowed us to characterize our subjects’ circadian rhythms with a high degree of temporal resolution.

Our study does possess some limitations. First, only one evaluable subject received the lower-dose light (albeit with a favorable “response”). Thus, further investigation of the effect of lower light intensity on the circadian rhythms of critically ill patients is warranted. Second, our study design resulted in significant attrition, thereby limiting the number of evaluable patients and suggesting a need for alternative study designs. Third, baseline differences in the timing of maximal aMT6s excretion may have influenced the results. Finally, we did not measure sleep, nor the intensity or temporal distribution of nursing care or sound levels.

Our results provide a basis for the investigation of timed light therapy as a treatment for circadian dysrhythmias. Future research should investigate the effect of this approach on clinically relevant outcomes including delirium, 28-day survival, and ventilator-free days, as well as long-term neuropsychiatric outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the nursing staff of the University of Iowa and University of Chicago ICUs for their assistance with this study. They also appreciate the assistance of Andy Potts, R.N., M.S.N., and Marina Aldrich, R.N.

Footnotes

B.K.G. received support for this study from K23HL088020 from the NHLBI, NIH. The Institute for Clinical and Translational Science at the University of Iowa is supported by the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award program, grant U54TR001356. The Clinical and Translational Science Award program is led by the NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. This publication's contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Contributions: B.K.G. takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript and was involved in the conception, hypothesis delineation, and design of the study; the acquisition and analysis of the data; and writing the paper. S.B.P. was involved in the design of the study and the acquisition of the data and reviewed the paper for critical content. E.V.C. was involved in the design of the study, the analysis of the data, and writing the paper. A.S.P. was involved in the design of the study and the acquisition of the data and reviewed the paper for critical content. J.B.H. was involved in the design of the study and the analysis of the data, and reviewed the paper for critical content. J.Z. was involved in the analysis of the data and writing the article.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0170LE on March 12, 2018

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Albrecht U. Timing to perfection: the biology of central and peripheral circadian clocks. Neuron. 2012;74:246–260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Effect of light on human circadian physiology. Sleep Med Clin. 2009;4:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archer SN, Laing EE, Möller-Levet CS, van der Veen DR, Bucca G, Lazar AS, et al. Mistimed sleep disrupts circadian regulation of the human transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E682–E691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316335111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans JA, Davidson AJ. Health consequences of circadian disruption in humans and animal models. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2013;119:283–323. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396971-2.00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Depner CM, Stothard ER, Wright KP., Jr Metabolic consequences of sleep and circadian disorders. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:507. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0507-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gehlbach BK, Chapotot F, Leproult R, Whitmore H, Poston J, Pohlman M, et al. Temporal disorganization of circadian rhythmicity and sleep-wake regulation in mechanically ventilated patients receiving continuous intravenous sedation. Sleep (Basel) 2012;35:1105–1114. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gazendam JAC, Van Dongen HPA, Grant DA, Freedman NS, Zwaveling JH, Schwab RJ. Altered circadian rhythmicity in patients in the ICU. Chest. 2013;144:483–489. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisani MA, Friese RS, Gehlbach BK, Schwab RJ, Weinhouse GL, Jones SF. Sleep in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:731–738. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201411-2099CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danielson SJ, Rappaport CA, Loher MK, Gehlbach BK. Looking for light in the din: an examination of the circadian-disrupting properties of a medical ICU. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.12.006. [online ahead of print] 28 Mar 2018; DOI: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gehlbach BK, Patel SB, Potts A, Pohlman A, Doerschug K, Schmidt GA, et al. Phase shifting effects of a sleep and circadian rhythm promotion protocol on the circadian rhythm of 6-sulfatoxymelatonin excretion in critically ill patients [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A3134. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeitzer JM, Dijk DJ, Kronauer R, Brown E, Czeisler C. Sensitivity of the human circadian pacemaker to nocturnal light: melatonin phase resetting and suppression. J Physiol. 2000;526:695–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bojkowski CJ, Arendt J, Shih MC, Markey SP. Melatonin secretion in humans assessed by measuring its metabolite, 6-sulfatoxymelatonin. Clin Chem. 1987;33:1343–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahlberg R, Tilmann A, Salewski L, Kunz D. Normative data on the daily profile of urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin in healthy subjects between the ages of 20 and 84. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine consensus conference. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]