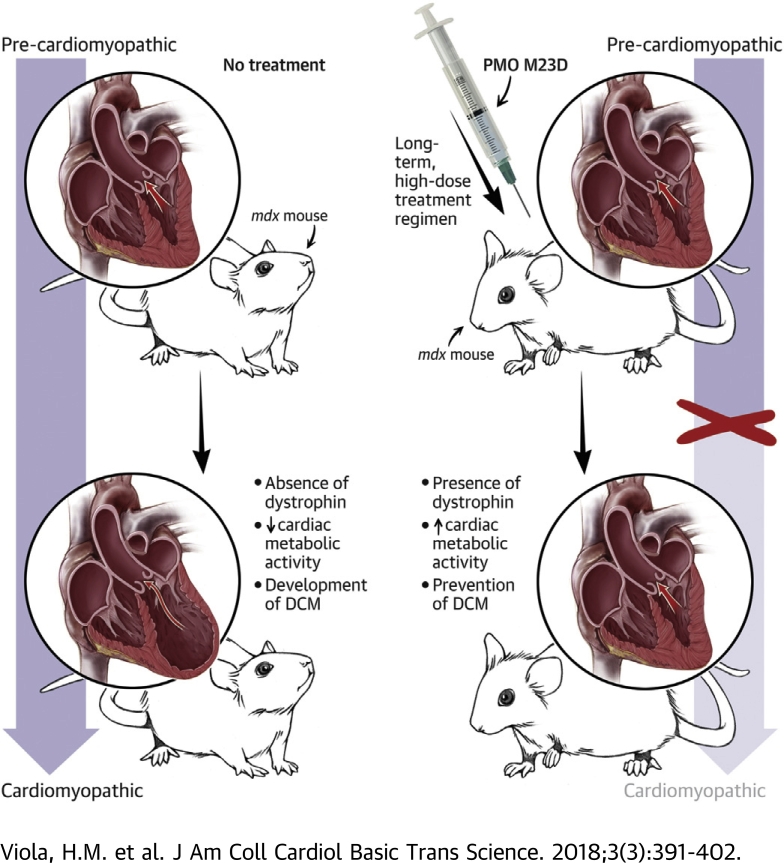

Visual Abstract

Key Words: cardiomyopathy, L-type calcium channels, mitochondria

Abbreviations and Acronyms: DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; ICa-L, L-type Ca2+ channel; JC-1, 5,5',6,6'-tetrachloro-1,1',3,3'-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide; mdx, murine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy; PMO, phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; wt, wild type; Ψm, mitochondrial membrane potential

Highlights

-

•

DMD patients develop reduced myocardial metabolic activity and dilated cardiomyopathy due to the absence of dystrophin.

-

•

Current clinical trials demonstrate patients receiving PMO therapy exhibit accumulation of functional dystrophin and improved ambulation; however, cardiac abnormalities remain.

-

•

Utilizing the murine model of the disease (mdx), we identify a novel early-intervention PMO treatment regimen for the prevention of DMD cardiomyopathy.

-

•

Pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice were administered a nontoxic, long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen.

-

•

Treated mdx mice exhibited accumulation of functional dystrophin, restoration of cardiac metabolic activity, and did not develop the cardiomyopathy.

Summary

Current clinical trials demonstrate Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) patients receiving phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO) therapy exhibit improved ambulation and stable pulmonary function; however, cardiac abnormalities remain. Utilizing the same PMO chemistry as current clinical trials, we have identified a non-toxic PMO treatment regimen that restores metabolic activity and prevents DMD cardiomyopathy. We propose that a treatment regimen of this nature may have the potential to significantly improve morbidity and mortality from DMD by improving ambulation, stabilizing pulmonary function, and preventing the development of cardiomyopathy.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a fatal X-linked disease that affects 1 in 3,600 to 6,000 live male births 1, 2. It is caused by a lack of expression of dystrophin, an important cytoskeletal protein that plays a role in maintaining structural integrity in muscle cells (3). DMD patients exhibit muscle degeneration primarily in skeletal muscles (2). However, in addition to this, patients develop dilated cardiomyopathy that is associated with cytoskeletal protein disarray, contractile dysfunction, and reduced myocardial metabolic activity 4, 5. Approximately 20% of DMD patient deaths result from dilated cardiomyopathy (6).

Approximately 70% of DMD-causing mutations are located between exons 45 and 55 (7). The effect of several therapeutic approaches on DMD cardiac pathology have been investigated, with varying degrees of efficacy reported (8). Effective therapy must be able to induce expression of dystrophin while improving function without inducing toxicity. We have utilized a nontoxic phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO) therapy that induces skipping of dystrophin exon 51, resulting in accumulation of truncated, functional dystrophin. Current clinical trials demonstrate improved ambulation and stable pulmonary function in DMD patients receiving this treatment (30 or 50 mg/kg/week, Phase 2b Eteplirsen Study 202, Sarepta Therapeutics, Cambridge, Massachusetts) 9, 10. However, established cardiac abnormalities consistent with the DMD phenotype remain in these patients.

Using the murine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (mdx mice), we previously identified a novel mechanism by which absence of expression of dystrophin leads to myocardial metabolic dysfunction and compromised cardiac function in mdx hearts (11). This involves a structural and functional communication breakdown between the L-type Ca2+channel (ICa-L) and mitochondria. We have demonstrated that in addition to regulation of calcium-dependent mechanisms, the cardiac ICa-L plays an important role in regulating mitochondrial function through structural and functional communication via cytoskeletal proteins, independently of alterations in intracellular calcium 11, 12. Myocytes isolated from mdx mice that exhibit cytoskeletal disarray due to the absence of dystrophin, exhibit impaired ICa-L regulation of mitochondrial function (11). Importantly, this lack of response occurs in both pre- and post-cardiomyopathic mdx mice, suggesting that metabolic dysfunction precedes development of the cardiomyopathy (11).

We have previously shown that long-term, low-dose treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with an antisense oligomer of the same PMO chemistry administered clinically to DMD patients (13), partially restores mitochondrial function in response to activation of ICa-L in cardiac myocytes isolated from treated mice (11). Because metabolic dysfunction precedes the mdx cardiomyopathy, we reasoned that early PMO treatment and subsequent restoration of metabolic function may prove beneficial in the prevention of DMD cardiomyopathy. Here, we treated mdx mice long term with a high concentration (120 mg/kg/week), yet non-toxic PMO dosing regimen that commenced prior to the development of the cardiomyopathy. This treatment regimen completely restored mitochondrial function and prevented subsequent development of the cardiomyopathy.

Methods

Animal model and PMO treatments

Male C57BL/10ScSn-Dmdmdx/Arc (mdx) and C57BL/10ScSnArc wild-type (wt) mice were used for all studies. Experiments were performed in myocytes isolated from 3 to 9 mice for each experimental group. Four- to 5-day-old mdx mice were treated with either 40 mg/kg PMO M23D (Sarepta Therapeutics), 3× per week or 120 mg/kg PMO M23D once per week by subcutaneous injection for 3 weeks. In other studies, 24-week-old C57BL/10ScSn-Dmdmdx/Arc (mdx) mice were treated with 40 mg/kg PMO M23D 3× per week for 19 weeks (M23D was a generous gift from Sarepta Therapeutics). Age-matched untreated wt and mdx counterparts were used for comparisons. All animal studies were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia and Murdoch University in accordance with the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes (14).

Ribonucleic acid preparation and RT-PCR analysis

Total ribonucleic acid was extracted from cardiac muscle using a MagMax-96 Total RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Melbourne, Australia), and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed for analysis of exons 20 to 26 using a Superscript III One-step PCR system with Platinum Taq (Invitrogen, Melbourne, Australia). Primers are listed in Table 1. Detailed methods are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Table 1.

RT-PCR Primers Used to Amplify Dystrophin Exons 20 to 26

| PCR Primer | Sequence 5′-3′ | Expected Size (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse exon 20-26 outer | MExon20F | CAGAATTCTGCCAATTGCTGAG | |

| MExon26R | TTCTTCAGCTTGTGTCATCC | ||

| Mouse exon 20-26 inner | MExon20F | CCCAGTCTACCACCCTATCAGAGC | 900 |

| MExon26R | CCTGCCTTTAAGGCTTCCTT |

bp = base pairs; RT-PCR = reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Immunoblotting and immunostaining

Dystrophin in cardiac muscle was assessed by immunoblot with NCL-DYS2 (Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, United Kingdom) (15), using a protocol derived from previously described methodology 16, 17. Immunohistochemistry was performed on heart, diaphragm, and tibialis anterior cryosections using rabbit anti-dystrophin primary antibody (ab15277, 1:200 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and Alexafluor 488 secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulins, A11008, 1:400 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Melbourne, Australia). Detailed methods are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Isolation of ventricular myocytes

Animals were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbitone sodium (240 mg/kg) prior to excision of the heart. Cells were isolated based on methods described 11, 18. Detailed methods are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Fluorescent studies

All studies were performed in intact mouse cardiac myocytes at 37°C. Fluorescent indicator 5,5',6,6'-tetrachloro-1,1',3,3'-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) was used to measure mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm) as described previously (19). Flavoprotein autofluorescence was used to measure flavoprotein oxidation based on previously described methods 20, 21. Detailed methods are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide assay

The rate of cleavage of 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide to formazan by the mitochondrial electron transport chain was measured spectrophotometrically as previously described 11, 12. Each n represents the number of replicates for each treatment group from myocytes isolated from a total of 9 wt, 6 mdx, and 6 PMO-treated mdx hearts. Detailed methods are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Echocardiography

Echocardiographic measurement of left ventricular function were performed on mice under light methoxyflurane anesthesia using an i13L probe on a Vivid 7 Dimension (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) as previously described 20, 21. Quantitative measurements represent the average of 24- 30-, 38-, and 43-week-old wt (n = 3), mdx (n = 3 to 5), and PMO-treated mdx (n = 4 to 9) mice. Detailed methods are provided in the Supplemental Appendix.

Serum parameters of kidney and liver toxicity following in vivo treatment

Following treatment, mice were anaesthetized, terminal blood collected, and serum extracted to measure kidney and liver toxicity. Urea, creatinine, and alanine transaminase concentration was assessed using urea, creatinine, and alanine transaminase assay kits (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, California).

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05 using the Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data (GraphPad Prism version 5.04, GraphPad, San Diego, California).

Results

Effect of treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with a short-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen

We previously demonstrated that treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with 10 mg/kg/week PMO for 24 weeks partially restored increases in Ψm and metabolic activity in response to activation of ICa-L in cardiac myocytes (11). Because the half-life of dystrophin is shorter in cardiac versus skeletal muscle (22), a higher PMO dose may induce more skipping of dystrophin exon 23 and accumulation of functional dystrophin in the heart. Therefore, we investigated the effect of a short-term, but high-concentration PMO treatment (120 mg/kg/week), on Ψm and metabolic activity. First we treated 4- to 5-day old pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice (11), with either 40 mg/kg PMO 3× per week for 3 weeks, or 120 mg/kg PMO once per week for 3 weeks. Cardiac uptake of PMO was then determined as evidence of exon skipping using RT-PCR. Treatment with both dosing regimens resulted in exon skipping (Figure 1A).

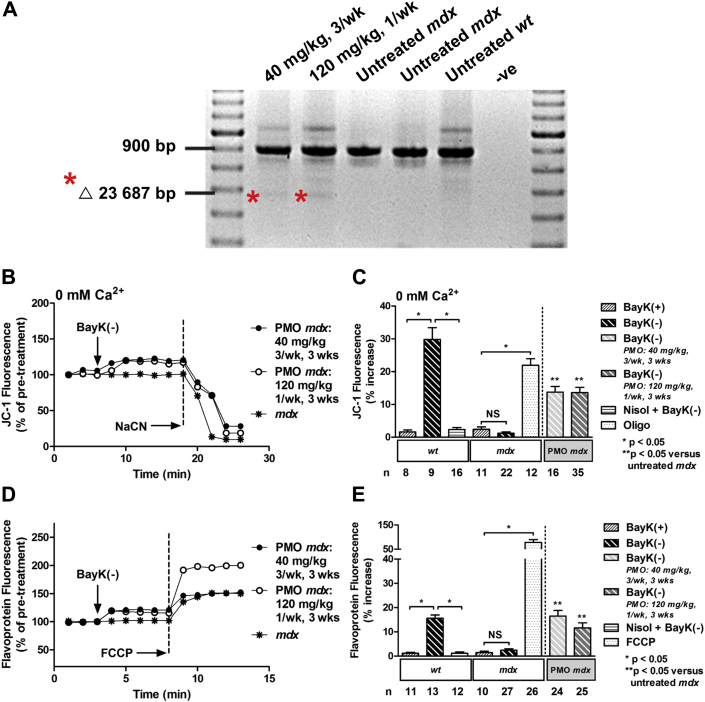

Figure 1.

Short-Term, High-Dose Treatment of 4- to 5-Day-Old mdx Mice With PMO Results in Exon Skipping of Dystrophin, and Partial Restoration of Ψm and Flavoprotein Oxidation in Response to Activation of ICa-L

(A) Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on cardiac ribonucleic acid from phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO)-treated murine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (mdx) mice demonstrating exon 23 skipping (Δ 23 687 base pairs [bp]), as indicated by asterisks, and untreated mdx and wild-type (wt) control mice. (B) Representative ratiometric 5,5',6,6'-tetrachloro-1,1',3,3'-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) fluorescence recorded in myocytes from PMO-treated mdx mice, and an untreated mdx mouse before and after exposure to 10 μM BayK(–) under calcium-free conditions (0 mM Ca2+). (C) Mean ± SEM of JC-1 fluorescence for all myocytes exposed to drugs as indicated. (D) Representative traces of flavoprotein fluorescence recorded in myocytes from PMO-treated mdx mice and an untreated mdx mouse before and after exposure to 10 μM BayK(–). (E) Mean ± SEM of flavoprotein fluorescence for all myocytes exposed to drugs as indicated. PMO treatments: 40 mg/kg (3×/week) or 120 mg/kg (1×/week) for 3 weeks. BayK(+) = 10 μM; FCCP = 50 μM carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone; ICa-L = L-type Ca2+ channel; NaCN = 40 mM sodium cyanide; Nisol = 15 μM nisoldipine; NS = not significant; Oligo, 20 μM oligomycin; -ve = negative control; Ψm, mitochondrial membrane potential.

Next, we examined the efficacy of a short-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen on alterations in Ψm and metabolic activity induced by activation of ICa-L in cardiac myocytes. Consistent with previous findings under calcium-free conditions, application of ICa-L agonist BayK(–) elicited a significant increase in Ψm assessed as changes in JC-1 fluorescence in myocytes from 4-week-old wt mice that was attenuated with application of ICa-L antagonist nisoldipine (Figure 1C) 11, 12. No change in Ψm was observed in age-matched mdx myocytes (Figures 1B and 1C). However, myocytes from 4-week-old mdx mice treated with either PMO treatment regimen exhibited a significant increase in Ψm in response to BayK(–) (Figures 1B and 1C). Both treatment regimens partially rescued the response compared with the response of wt mice. Application of the (+)enantiomer of BayK that does not act as an agonist (BayK[+]) did not significantly alter Ψm in wt or mdx myocytes (Figure 1C). As a positive control, mdx myocytes were exposed to adenosine triphosphatase synthase blocker oligomycin, resulting in a significant increase in JC-1 fluorescence demonstrating functional electron transport (Figure 1C). Mitochondrial electron transport blocker NaCN collapsed Ψm in all myocytes demonstrating that the signal was mitochondrial in origin (Figure 1B). These data indicate that treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with a short-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen partially restores the increase in Ψm measured in response to activation of ICa-L.

Metabolic activity is dependent on oxygen consumption and electron flow down the inner mitochondrial membrane. Therefore, we examined alterations in mitochondrial electron transport in intact cardiac myocytes by measuring alterations in flavoprotein oxidation. Consistent with previous findings, BayK(–) caused a significant increase in flavoprotein oxidation in myocytes from 4-week-old wt mice that was prevented with nisoldipine (Figure 1E) (11). No alteration was observed in age-matched mdx myocytes (Figures 1D and 1E). However, myocytes isolated from 4-week-old mdx mice treated with either PMO dosing regimen exhibited a significant increase in flavoprotein oxidation in response to BayK(–) (Figures 1D and 1E). Both treatment regimens rescued the response. BayK(+) did not significantly alter flavoprotein oxidation in wt or mdx myocytes (Figure 1E). Mitochondrial electron transport chain uncoupler carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone increased flavoprotein signal confirming the signal was mitochondrial in origin (Figures 1D and 1E). These data indicate that treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with a short-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen restores metabolic activity in the mdx heart.

Effect of treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen

We investigated whether a long-term, high PMO treatment dose (120 mg/kg/week) would more effectively restore Ψm and metabolic activity in mdx cardiac myocytes, compared with short-term treatment. The 24-week-old pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice were treated with 40 mg/kg PMO M23D 3× per week for 19 weeks. Rather than 1 weekly dose, a triweekly treatment regimen was used because multiple injections may improve PMO distribution and prolong half-life (22). Cardiac uptake of PMO was then examined by assessing exon skipping using RT-PCR and detecting the presence of dystrophin on immunoblot and immunohistochemistry. This treatment regimen resulted in exon skipping (Figure 2A) and positive expression of dystrophin (Figures 2B and 2C).

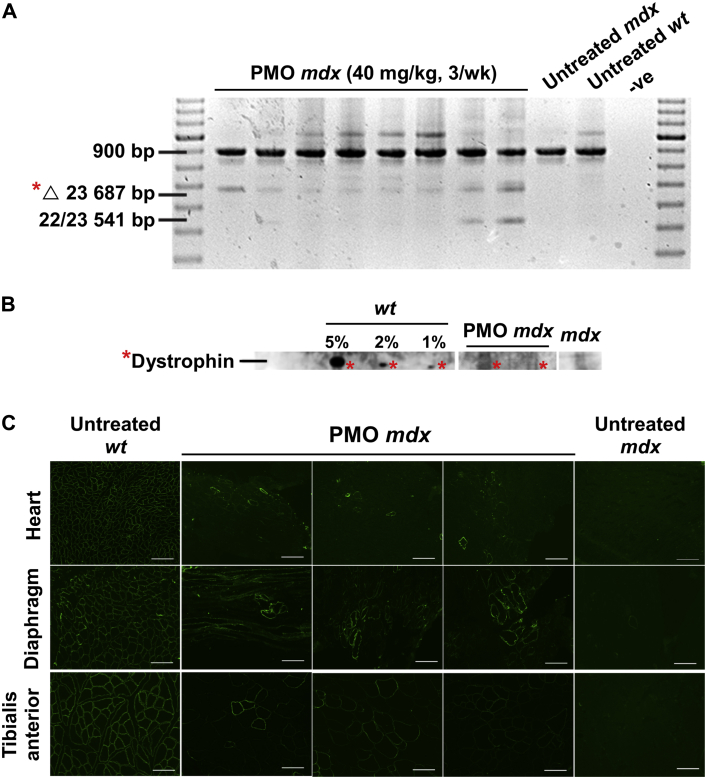

Figure 2.

Long-Term, High-Dose Treatment of 24-Week-Old mdx Mice With PMO Results in Exon Skipping and Expression of Dystrophin

(A) Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction performed on cardiac muscle ribonucleic acid from PMO-treated mdx mice demonstrating exon 23 skipping (Δ 23 687 bp) (indicated by asterisk) and age-matched untreated mdx and wt control mice. The 22/23 541 bp amplicon represents an out-of-frame transcript missing exons 22 and 23 and has been previously reported 37, 38. (B) Immunoblot performed on cardiac muscle from untreated wt (5%, 2%, and 1% dilutions), untreated mdx mice (undiluted), and PMO-treated mdx mice (undiluted) demonstrating presence of dystrophin (indicated by asterisk). (C) Immunostaining of heart cryosections from untreated wt and mdx mice and PMO-treated mdx mice demonstrating presence of dystrophin. Bars = 100 μm. PMO treatment: 40 mg/kg PMO 3× per week for 19 weeks; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

We also examined the efficacy of a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen on restoring Ψm in isolated cardiac myocytes. Under calcium-free conditions, BayK(–) elicited a significant increase in Ψm in wt myocytes that was attenuated with nisoldipine (Figure 3B). No alteration was observed in age-matched mdx myocytes (Figures 3A and 3B). However, treatment of mdx mice with 40 mg/kg PMO 3× per week for 19 weeks completely rescued this response (Figures 3A and 3B). The response was attenuated with nisoldipine (Figure 3B). BayK(+) did not significantly alter Ψm in wt or mdx myocytes (Figure 3B). Oligomycin induced a significant increase in JC-1 fluorescence in mdx myocytes demonstrating functional electron transport (Figure 3B). Application of NaCN collapsed Ψm in all myocytes demonstrating that the signal was mitochondrial in origin (Figure 3A). These data indicate that treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen completely restores the increase in Ψm in response to activation of ICa-L.

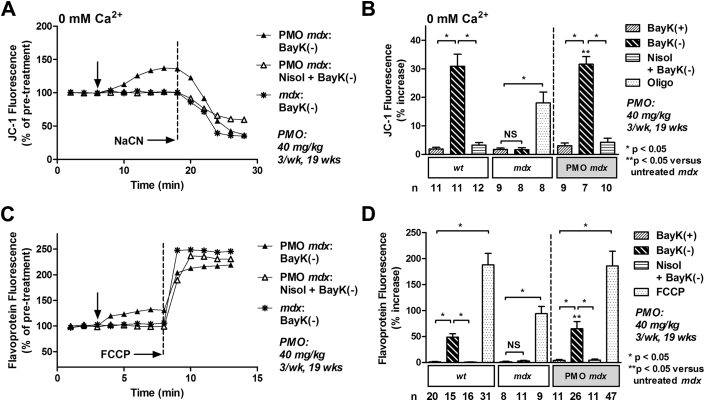

Figure 3.

Long-Term, High-Dose Treatment of 24-Week-Old mdx Mice With PMO Completely Restores Ψm and Flavoprotein Oxidation in Response to Activation of ICa-L

(A) Representative ratiometric JC-1 fluorescence recorded in myocytes from a PMO-treated mouse and an untreated mdx mouse before and after exposure to 10 μM BayK(–) ± 15 μM nisoldipine (Nisol) under calcium-free conditions (0 mM Ca2+). Arrow indicates addition of drugs. (B) Mean ± SEM of JC-1 fluorescence for all myocytes exposed to drugs as indicated. (C) Representative traces of flavoprotein fluorescence recorded in myocytes from a PMO-treated mouse and an untreated mdx mouse before and after exposure to 10 μM BayK(–) ± 15 μM nisoldipine (Nisol). Arrow indicates addition of drugs. (D) Mean ± SEM of flavoprotein fluorescence for all myocytes exposed to drugs as indicated. BayK(+) = 10 μM; FCCP = 50 μM carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone; NaCN = 40 mM sodium cyanide; PMO treatment = 40 mg/kg PMO 3× per week for 19 weeks; Oligo = 20 μM oligomycin; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

We also investigated the efficacy of a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen on metabolic activity. BayK(–) caused a significant increase in flavoprotein oxidation in myocytes from 43-week-old wt mice that was prevented with nisoldipine (Figure 3D). No alteration was observed in age-matched mdx myocytes (Figures 3C and 3D). However, myocytes isolated from 43-week-old mdx mice treated with PMO exhibited a significant increase in flavoprotein in response to BayK(–) that was attenuated by nisoldipine (Figures 3C and 3D). BayK(+) did not significantly alter flavoprotein oxidation in wt or mdx myocytes (Figure 3D). Carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone increased flavoprotein signal in all myocytes confirming the signal was mitochondrial in origin (Figures 3C and 3D).

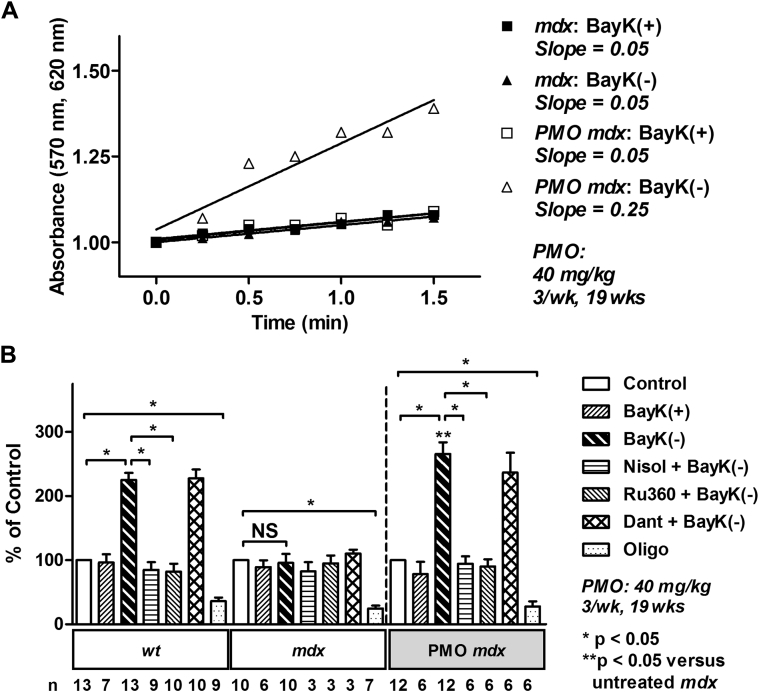

Metabolic activity was also assessed by measuring alterations in mitochondrial electron transport in intact cardiac myocytes, as formation of formazan from tetrazolium salt (3-[4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl]-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide). Consistent with previous findings, BayK(–) elicited a significant increase in metabolic activity in 43-week-old wt mice that was prevented with nisoldipine (Figure 4B) (11). The response was also attenuated with mitochondrial calcium uniporter (mitochondrial calcium uptake) blocker Ru360, but not with ryanodine receptor (sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release) blocker dantrolene (Figure 4B). No alteration was observed in age-matched mdx myocytes (Figures 4A and 4B). However, myocytes isolated from 43-week-old mdx mice treated with PMO exhibited a significant increase in metabolic activity in response to BayK(–) that could be attenuated by nisoldipine or Ru360, but not dantrolene (Figures 4A and 4B). BayK(+) did not significantly alter metabolic activity in wt, mdx, or PMO-treated mdx myocytes (Figures 4A and 4B). Oligomycin induced a significant decrease in metabolic activity in all myocytes demonstrating the myocytes were metabolically active (Figure 4B). These data indicate that treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen restores metabolic activity in the mdx heart.

Figure 4.

Long-Term, High-Dose Treatment of 24-Week-Old mdx Mice With PMO Completely Restores Metabolic Activity in Response to Activation of ICa-L

(A) Formation of formazan measured as change in absorbance in myocytes from untreated wt and mdx mice and PMO-treated mice (40 mg/kg PMO 3× per week for 19 weeks), after addition of 10 μM BayK(+) or BayK(–). (B) Mean ± SEM of increases in absorbance for all myocytes exposed to drugs as indicated. Dant = 20 μM dantrolene; Nisol = 15 μM nisoldipine; Oligo = 20 μM oligomycin; Ru360 = 15 μM; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen prevents the development of cardiomyopathy

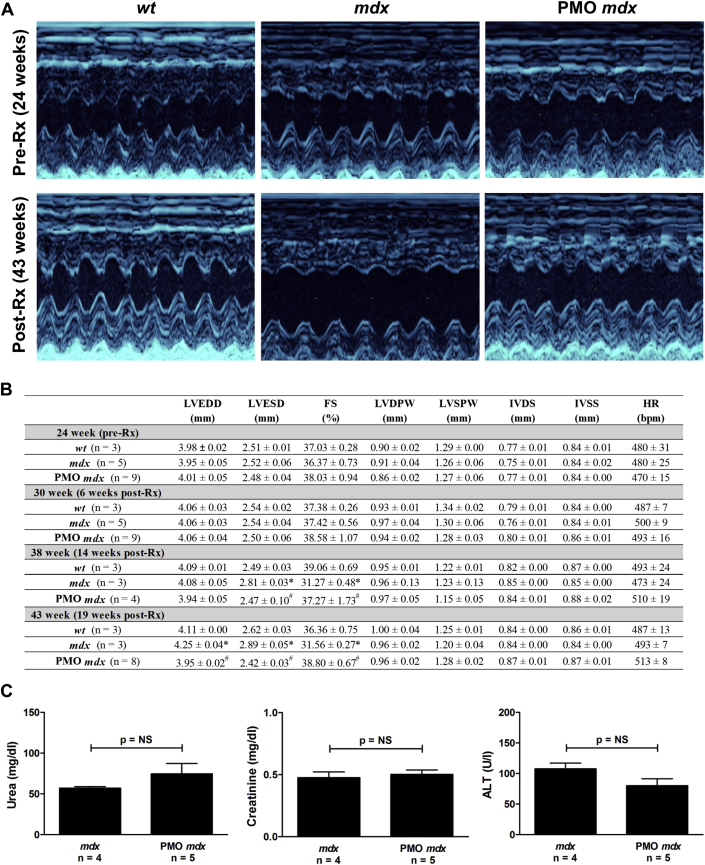

We examined the efficacy of a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen on the development of cardiomyopathy. Serial echocardiography was performed on mdx mice before and after treatment with 40 mg/kg PMO M23D 3× per week for 19 weeks. Twenty-four-week-old mdx mice exhibited no significant difference in any echocardiographic parameter compared with untreated wt mice, indicating that these mice were pre-cardiomyopathic (Figures 5A and 5B). Consistent with the development of dilated cardiomyopathy, untreated mdx mice, compared with age-matched untreated wt mice, exhibited a significant increase in left ventricular end-systolic diameter (from 38 weeks) and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (at 43 weeks) and a significant decrease in fractional shortening (from 38 weeks) (Figures 5A and 5B). PMO treatment significantly decreased left ventricular end-systolic diameter (from 38 weeks) and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (at 43 weeks) and significantly increased fractional shortening (from 38 weeks) to values comparable to those of age-matched untreated wt counterparts (Figures 5A and 5B). These data indicate that treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen prevents development of mdx cardiomyopathy.

Figure 5.

Long-Term, High-Dose Treatment of 24-Week-Old mdx Mice With PMO Prevents Development of mdx Cardiomyopathy and Is Not Toxic

(A) Representative images of serial echocardiographic measurements from PMO-treated mdx mice and untreated wt and mdx mice pre- (24 weeks) and post-treatment (Rx; 43 weeks). (B) Mean ± SEM of all echocardiographic measurements. *p < 0.05 compared with untreated age-matched wt; #p < 0.05 compared with untreated age-matched mdx. (C) Mean ± SEM of urea, creatinine, and alanine transaminase (ALT) concentrations in PMO-treated mice compared to untreated mdx mice. bpm = beats/min; FS = fractional shortening; HR = heart rate; IVDS = intraventricular septum in diastole; IVSS = intraventricular septum in systole; LVEDD = left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVESD = left ventricular end-systolic diameter; LVDPW = left ventricular posterior wall in diastole; LVSPW = left ventricular posterior wall in systole; PMO Rx = 40 mg/kg PMO 3× per week for 19 weeks; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen is not toxic in vivo

Following long-term, high-dose PMO treatment, serum was extracted and used to measure kidney and liver toxicity. Urea, creatinine, and alanine transaminase concentrations were measured. We found no evidence of toxicity following treatment of the mice (Figure 5C).

Discussion

DMD patients exhibit progressive muscle degeneration primarily in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Advances in respiratory care have resulted in an increase in life expectancy for DMD patients over the last half-century; however, this prolongation of life has been accompanied by an increasing number of patients experiencing from an ultimately fatal dilated cardiomyopathy (23). The effect of several therapeutic approaches on DMD cardiac pathology have been investigated, with varying degrees of efficacy (8). This includes use of antisense oligonucleotides to alter exon or splice site selection in order to restore the correct dystrophin reading frame (24) and production of a truncated, but functional dystrophin protein.

Because approximately 70% of DMD-causing mutations are located between exons 45 and 55 (7), the majority of antisense oligonucleotides therapeutic development to date has focused on exon skipping within this region. It has been estimated that skipping exons 51, 45, and 53 could benefit 13%, 8.1%, and 7.7% of all DMD mutations, respectively (25). Two types of modified antisense oligonucleotides have been evaluated clinically for exon 51 skipping in DMD patients, including 2′O-methylated phosphorothioate and PMO. Both have elicited recovery in skeletal and pulmonary function, but with limited ability to prevent progressive cardiac decline (8).

2′O-methylated phosphorothioate oligonucleotides consist of a phosphorothioate backbone that contains internucleotide linkages that confer a negative charge, resulting in enhanced binding to circulatory proteins and an increase in plasma half-life (26). A phase 1 to 2a trial of this compound reported an improvement in the 6-min walk test in DMD patients 25 weeks following commencement of treatment (0.5 to 6 mg/kg for 5 weeks, followed by 6 mg/kg for 12 weeks) versus placebo cohorts, but by week 49, the difference was no longer significant 27, 28. A subsequent phase 3 double-blinded placebo-controlled study involving prolonged treatment of DMD patients with 6 mg/kg/week (48 weeks) did not improve ambulation (6-min walk test) or secondary assessments of motor function (29). Furthermore, adverse events including kidney and liver toxicity, likely to be off-target effects of the 2′O-methylated phosphorothioate backbone, were reported in 46% of patients 27, 28, 30.

PMO consist of a 6-membered morpholine ring moiety, joined by phosphorodiamidate linkages. Unlike phosphorothioates, the backbone carries no charge at physiological pH, reducing off-target effects (31). PMO are nontoxic and stable (32). A phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled study involving treatment of 8 DMD boys (7 to 13 years of age) with 30 or 50 mg/kg/week (24 weeks) demonstrated a significant increase in dystrophin production in these patients (Eteplirsen Study 201, Sarepta Therapeutics). With this, the placebo group joined the PMO treatment group. All 12 patients continued receiving PMO treatment in an ongoing extension study for over 3 years (phase 2b Eteplirsen Study 202, Sarepta Therapeutics) (9). At week 168, the continuously treated ambulatory patients continued to walk within 18% of their week-12 distance, whereas the placebo/delayed treatment cohort continued to walk within 23% of their week-36 distance (10). Pulmonary function remained stable in these patients, and the hallmark decline in respiration observed in DMD patients appears to have been repressed. Furthermore, no clinically significant treatment-related adverse events have been observed. However, cardiac abnormalities consistent with the DMD phenotype remain in these patients. Effective therapy must be able to improve cardiac function and prevent ultimately fatal dilated cardiomyopathy, without inducing toxicity.

The mdx mouse manifests a mild dystrophic phenotype relative to the human disease and is therefore not regarded as an ideal clinical model for DMD. However, it provides an excellent molecular model for the study of dystrophin function and novel therapeutics. Using the mdx mouse model of DMD, we previously identified that cytoskeletal disarray due to the absence of dystrophin results in impaired regulation of mitochondrial function by ICa-L (11). Importantly, we identified that this decrease in myocardial metabolic activity occurs in pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice and persists through to the development of the cardiomyopathy (11).

Cardiomyopathy in DMD patients shows variable onset and severity, with no clear correlation between genotype and phenotype. Conflicting reports on such an association are likely due to small sample size, variability in cardiac function analysis, clinical care and cardiac medications, and unverified consequences of the mutation on dystrophin transcript and/or protein 33, 34, 35. Patients with the same DMD genotype can show very different severity and age of onset of left ventricular dysfunction and, ultimately, survival (35). This confounds the interpretation of potential treatment-related effects. Although cardiomyopathy in the mdx mouse is relatively mild with late onset, this model has allowed us to investigate the mechanistic basis of metabolic dysfunction in the dystrophic heart and the consequences of partial restoration of a functional dystrophin. We have demonstrated that a long-term, low-dose PMO treatment regimen partially restores regulation of cardiac metabolic activity by ICa-L (11). Based on the success of current long-term, 30 to 50 mg/kg/week PMO trials on improving ambulation and pulmonary function, and the knowledge that the half-life of dystrophin is shorter in cardiac versus skeletal muscle (22), we reasoned that a higher PMO dose may induce a higher level of skipping of dystrophin exon 23 and expression of functional dystrophin in the mdx heart.

Initial studies indicated that treatment of pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with a high PMO dose (120 mg/kg/week) for 3 weeks was sufficient to induce exon skipping and partially rescue alterations in Ψm and metabolic activity in response to activation of ICa-L (Figure 1) (11). Based on these findings, we proposed that a long-term, high-dose treatment regimen would result in a more complete restoration of Ψm and metabolic activity. We find that administering pre-cardiomyopathic mdx mice with 40 mg/kg PMO 3× per week for 19 weeks induced exon skipping and expression of dystrophin in the heart (Figure 2), completely rescued alterations in Ψm and metabolic activity (Figures 3 and 4), prevented development of the cardiomyopathy, and, importantly, is not toxic in vivo (Figure 5). Consistent with previous studies, we find that PMO treatment results in accumulation of as little as 5% of normal dystrophin protein expression in mdx mice (Figure 2B) (36). Importantly, this is sufficient to result in functional improvement in the mdx heart (Figures 5A and 5B).

Using the mdx mouse model of DMD, we previously identified that cytoskeletal disarray due to the absence of dystrophin results in impaired regulation of mitochondrial function by ICa-L (11). Additionally, we identified that metabolic dysfunction precedes development of mdx cardiomyopathy (11). Here we find that a long-term, high-dose yet nontoxic PMO treatment regimen that commences prior to the development of mdx cardiomyopathy completely restores metabolic function and, subsequently, prevents development of the cardiomyopathy. This study utilized the same PMO chemistry used in current clinical trials demonstrating that DMD patients receiving this treatment exhibit improved ambulation and stable pulmonary function 9, 10. However, cardiac abnormalities consistent with the DMD phenotype remain in these patients. Based on our current findings, we propose that a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen that commences prior to the development of cardiomyopathy may have the potential to concurrently improve ambulation, stabilize pulmonary function, and prevent cardiomyopathy in DMD patients.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Advances in respiratory care have resulted in an increase in life expectancy for DMD patients over the last half-century; however, this prolongation of life has been accompanied by an increasing number of patients suffering from an ultimately fatal dilated cardiomyopathy. Approximately 20% of DMD patient deaths result from dilated cardiomyopathy. Current clinical trials demonstrate that PMO therapy induces skipping of dystrophin exon 51 and accumulation of functional dystrophin, and that these patients exhibit improved ambulation and stable pulmonary function; however, cardiac abnormalities remain. Effective therapy must be able to improve cardiac function and prevent ultimately fatal dilated cardiomyopathy without inducing toxicity. Utilizing the same PMO chemistry as current clinical trials, we have identified a nontoxic PMO treatment regimen to restore metabolic activity and prevent mdx cardiomyopathy.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: The efficacy of a long-term, high-dose PMO treatment regimen in DMD patients will now need to be determined. We propose that a treatment regimen of this nature may have the potential to significantly improve morbidity and mortality from DMD because in addition to improving ambulation and stabilizing pulmonary function, the treatment will prevent the development of cardiomyopathy in DMD patients.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and Australian Research Council (1062740). Dr. Viola is supported by a grant from Raine Priming (RPG50). Dr. Hool is a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellow (APP1002207). Dr. Fletcher and Ms. Adams were supported by grants from the Muscular Dystrophy Association USA (272200) and the National Health and Medical Research Foundation of Australia (1062740 and 1043758); and receive support from Sarepta Therapeutics. Dr. Fletcher is a consultant to Sarepta Therapeutics; and is named as inventor on patents licensed to Sarepta Therapeutics. The phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers used in this study were a gift from Sarepta Therapeutics (Cambridge, Massachusetts) to Sue Fletcher at Murdoch University, for the purpose of investigation of exon skipping and expression of dystrophin in the heart, diaphragm and tibialis anterior. All in vitro and in vivo assessment of cardiac function was performed in the Cardiovascular Electrophysiology Laboratory of Livia Hool at The University of Western Australia, where no financial benefit or research funds were received from Sarepta Therapeutics. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

All authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Basic to Translational Scienceauthor instructions page.

Appendix

References

- 1.Emery A.E. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet. 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bushby K., Finkel R., Birnkrant D.J., for the DMD Care Considerations Working Group Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:77–93. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao Q.Q., McNally E.M. The dystrophin complex: structure, function, and implications for therapy. Compr Physiol. 2015;5:1223–1239. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finsterer J., Stollberger C. The heart in human dystrophinopathies. Cardiology. 2003;99:1–19. doi: 10.1159/000068446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khairallah M., Khairallah R., Young M.E., Dyck J.R., Petrof B.J., Des Rosiers C. Metabolic and signaling alterations in dystrophin-deficient hearts precede overt cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirokova N., Niggli E. Cardiac phenotype of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: insights from cellular studies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;58:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muntoni F., Torelli S., Ferlini A. Dystrophin and mutations: one gene, several proteins, multiple phenotypes. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:731–740. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00585-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnstone V.P., Viola H.M., Hool L.C. Dystrophic cardiomyopathy-potential role of calcium in pathogenesis, treatment and novel therapies. Genes (Basel) 2017;8:E108. doi: 10.3390/genes8040108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendell J.R., Goemans N., Lowes L.P., for the Eteplirsen Study Group and Telethon Foundation DMD Italian Network Longitudinal effect of eteplirsen versus historical control on ambulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:257–271. doi: 10.1002/ana.24555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pane M., Mazzone E.S., Sormani M.P. 6 Minute walk test in Duchenne MD patients with different mutations: 12 month changes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e83400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viola H.M., Adams A.M., Davies S.M., Fletcher S., Filipovska A., Hool L.C. Impaired functional communication between the L-type calcium channel and mitochondria contributes to metabolic inhibition in the mdx heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E2905–E2914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402544111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viola H.M., Arthur P.G., Hool L.C. Evidence for regulation of mitochondrial function by the L-type Ca2+ channel in ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:1016–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gebski B.L., Mann C.J., Fletcher S., Wilton S.D. Morpholino antisense oligonucleotide induced dystrophin exon 23 skipping in mdx mouse muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1801–1811. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Health and Medical Research Council . 8th edition. National Health and Medical Research Council; Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: 2013. Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fletcher S., Honeyman K., Fall A.M., Harding P.L., Johnsen R.D., Wilton S.D. Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse after localised and systemic administration of a morpholino antisense oligonucleotide. J Gene Med. 2006;8:207–216. doi: 10.1002/jgm.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper S.T., Lo H.P., North K.N. Single section Western blot: improving the molecular diagnosis of the muscular dystrophies. Neurology. 2003;61:93–97. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000069460.53438.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicholson L.V., Davison K., Falkous G. Dystrophin in skeletal muscle. I. Western blot analysis using a monoclonal antibody. J Neurol Sci. 1989;94:125–136. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(89)90223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viola H.M., Davies S.M., Filipovska A., Hool L.C. The L-type Ca2+ channel contributes to alterations in mitochondrial calcium handling in the mdx ventricular myocyte. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H767–H775. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00700.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viola H.M., Arthur P.G., Hool L.C. Transient exposure to hydrogen peroxide causes an increase in mitochondria-derived superoxide as a result of sustained alteration in L-type Ca2+ channel function in the absence of apoptosis in ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2007;100:1036–1044. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000263010.19273.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viola H., Johnstone V., Cserne Szappanos H. The role of the L-type Ca2+ channel in altered metabolic activity in a murine model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science. 2016;1:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viola H., Johnstone V., Szappanos H.C. The L-type Ca channel facilitates abnormal metabolic activity in the cTnI-G203S mouse model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Physiol. 2016;594:4051–4070. doi: 10.1113/JP271681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu B., Lu P., Cloer C. Long-term rescue of dystrophin expression and improvement in muscle pathology and function in dystrophic mdx mice by peptide-conjugated morpholino. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spurney C.F. Cardiomyopathy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: current understanding and future directions. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:8–19. doi: 10.1002/mus.22097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilton S.D., Veedu R.N., Fletcher S. The emperor's new dystrophin: finding sense in the noise. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aartsma-Rus A., Fokkema I., Verschuuren J. Theoretic applicability of antisense-mediated exon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutations. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:293–299. doi: 10.1002/humu.20918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett C.F., Swayze E.E. RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goemans N.M., Tulinius M., van den Akker J.T. Systemic administration of PRO051 in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1513–1522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voit T., Topaloglu H., Straub V. Safety and efficacy of drisapersen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DEMAND II): an exploratory, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:987–996. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.GlaxoSmithKline. A clinical study to assess the efficacy and safety of gsk2402968 in subjects with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. 2013. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01254019. Accessed May 2018.

- 30.Flanigan K.M., Voit T., Rosales X.Q. Pharmacokinetics and safety of single doses of drisapersen in non-ambulant subjects with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: results of a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014;24:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douglas A.G., Wood M.J. Splicing therapy for neuromuscular disease. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2013;56:169–185. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amantana A., Iversen P.L. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of phosphorodiamidate morpholino antisense oligomers. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jefferies J.L., Eidem B.W., Belmont J.W. Genetic predictors and remodeling of dilated cardiomyopathy in muscular dystrophy. Circulation. 2005;112:2799–2804. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.528281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brinkmeyer-Langford C., Balog-Alvarez C., Cai J.J., Davis B.W., Kornegay J.N. Genome-wide association study to identify potential genetic modifiers in a canine model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:665. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2948-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashwath M.L., Jacobs I.B., Crowe C.A., Ashwath R.C., Super D.M., Bahler R.C. Left ventricular dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and genotype. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li D., Yue Y., Duan D. Marginal level dystrophin expression improves clinical outcome in a strain of dystrophin/utrophin double knockout mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mann C.J., Honeyman K., Cheng A.J. Antisense-induced exon skipping and synthesis of dystrophin in the mdx mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:42–47. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011408598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mann C.J., Honeyman K., McClorey G., Fletcher S., Wilton S.D. Improved antisense oligonucleotide induced exon skipping in the mdx mouse model of muscular dystrophy. J Gene Med. 2002;4:644–654. doi: 10.1002/jgm.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.