Abstract

Factorial 2 × 2 designs can be used to combine evaluation of two treatments in a single study. The standard analysis approach is based on a factorial analysis that evaluates each treatment by pooling data over the other treatment. This approach relies on the assumption that the effect of each treatment is not substantially affected by the other treatment. In many oncology settings, this no-interaction assumption cannot be adequately supported at the time the trial is designed. In this Commentary, we consider current practices for the design and analysis of factorial trials by performing a survey of factorial treatment trials published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Journal of Clinical Oncology, and the New England Journal of Medicine (2007–2016). The protocol-specified sample size was derived based on the factorial (pooled) analysis in 96.7% of the 30 identified trials, and the factorial analysis was specified as the primary analysis in 90.0% of these identified trials. An interaction complicating study interpretation was reported in 16.7% of the trials. We provide recommendations for matching the trial analysis and design to the study goals to account for possible interaction and illustrate the recommendations on the data from several published trials.

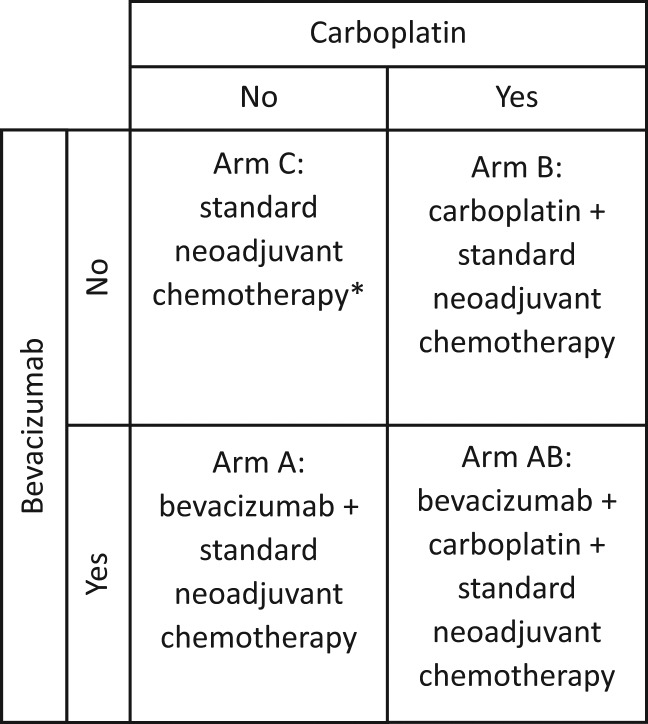

The randomized clinical trial (RCT) is the gold standard for definitive evaluation of new therapies. As RCTs require considerable resource and time commitment, there is the desire to optimize their design efficiency. For example, rather than testing two new treatments in two separate RCTs, it is sometimes possible to evaluate two new treatments (A and B) in a single RCT. A popular design to do this is the 2 × 2 factorial design, which randomly assigns patients to one of four treatments: a control arm (arm C), treatment A (arm A), treatment B (arm B), and a combination of treatments A and B (arm AB). For example, to assess the role of bevacizumab and carboplatin in neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer, CALGB 40603 randomly assigned patients to the standard chemotherapy (arm C), bevacizumab + standard chemotherapy (arm A), carboplatin + standard chemotherapy (arm B), or bevacizumab + carboplatin + standard chemotherapy (arm AB) (Figure 1). (For a more general definition of factorial designs, see the Supplementary Materials, available online.)

Figure 1.

CALGB 40603 (15): 2 × 2 factorial design: 1:1:1:1 randomization between the four arms. *Standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy backbone: paclitaxel weekly for 12 weeks followed by dose-dense doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide for four cycles.

If one assumes no (statistical) interaction between the treatments A and B, that is, that the beneficial effect of one treatment (if any) does not change with presence or absence of the other treatment, then one can use a factorial analysis that evaluates each treatment by pooling data over the other treatment. For example, in CALGB 40603, the effect of bevacizumab (treatment A) was estimated by pooling outcomes of patients that were assigned to the bevacizumab-containing arms (A and AB) and comparing them with the pooled outcomes of patients assigned to the arms that do not include bevacizumab (C and B); this comparison was stratified by treatment B. A factorial analysis allows one to assess both treatments using resources required for the evaluation of one treatment. Indeed, an often stated motivation for the factorial design is its efficiency in terms of the number of required patients (1). However, Green et al. (2) noted that making the no-interaction assumption “may lead to unacceptable chances of incorrect conclusions or inconclusive results, which cannot be overcome by analytic strategies” and strongly cautioned against using factorial analyses. In particular, when the no-interaction assumption is not justified (as, for example, may often be the case when the treatments being combined have overlapping toxicities), designing a study based on the factorial analysis may lead to missing an active treatment or erroneously recommending an ineffective combination.

In this Commentary, we emphasize the distinction between a factorial trial design, which refers to the factorial 2 × 2 treatment assignment, and a factorial analysis (of the factorial trial design), which evaluates each treatment by pooling over the other treatment. The purpose of the Commentary is to examine analysis strategies being used in current applications of factorial designs (by surveying published factorial treatment trials), to briefly review the statistical approaches for evaluation of two treatments in the same trial, and to provide recommendations for matching the study design to the study goal.

Survey of Factorial Designs

To examine the current use of factorial designs and their statistical analysis methods, we searched for phase III cancer treatment studies using factorial designs published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Journal of Clinical Oncology, and New England Journal of Medicine in the last 10 years (2007–2016); see the Supplementary Materials (available online) for details. We excluded cancer-control/symptom trials because they typically have complex multifaceted goals and end points that require complicated analyses. Our search identified 30 treatment trials that used 2 × 2 factorial designs. Characteristics of the trials are summarized in Table 1; specifics of the statistical design for each study were ascertained from the publication and the study protocol when available. For all but one trial, the protocol-specified sample size was based on a factorial analysis (96.7% of the trials). A factorial analysis was the primary analysis in 27 (90.0%) of the studies; in the remaining three trials, the primary analysis first tested for an interaction, with a factorial (individual-arm) analysis performed when the interaction test was statistically not-significant (significant). Among the 30 trials, five (16.7%) reported the presence of an interaction that complicated study interpretation (all of the interactions were negative [antagonistic]). Only 66.7% of the publications presented outcomes by treatment arm; some of the trials that did not report outcome by arm stated that there was no interaction.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 30* factorial trials identified in the survey

| Trial characteristic | Proportion, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Trials that required protocol-specified sample size based on a factorial analysis | 29 (96.7) |

| Primary analysis | |

| Factorial | 27 (90.0) |

| Test interaction -> factorial or arm-specific† | 3 (10.0) |

| Trials that reported presence of interaction that complicated study interpretation | 5 (16.7) |

| Trials that reported results by treatment arm | 18 (66.7)‡ |

Search criteria and list of trials are given in the Supplementary Materials (available online). Out of the 30 trials, three used a partial 2 × 2 design where only a subgroup of patients were randomly assigned to the second factor, and two used a two-stage randomization.

The primary analysis first tested for an interaction, with a factorial analysis (individual arm–specific analysis) performed when the interaction test was statistically not-significant (significant).

Two trials had different maturity for the two factorial questions, and one trial report is an interim futility report for one of the factors. Therefore, these three trials are not counted in the denominator.

Approaches to Evaluating Two Treatments in the Same Trial

We now review RCT designs for evaluating efficacy of two new treatments (A and B) and possibly their combination in a single study. In most cancer treatment settings, the assumption of no interaction cannot generally be well supported at the time of the study design. Furthermore, few factorial designs (and none of the 30 in our survey) have adequate power to detect the level of interaction that can qualitatively affect study conclusions (because this would require roughly quadrupling the study sample size) (3). Therefore, when the no-interaction assumption is not justified, one needs to either consider a three-arm RCT design (A, B, and C) or a factorial design with alternative analysis approaches, which will now be discussed.

Table 2 presents the (relative) sample size requirements for commonly used approaches to the evaluation of two new treatments in a single trial. The best choice of the design and/or analysis approach depends on the questions the study is intended to address (2): 1) Is the goal to independently evaluate two treatments in a single clinical trial, that is, to address two separate questions, whether treatment A works and whether treatment B works? or 2) Is the goal of the study to determine how treatments A and B work with and without the other treatment (including whether the combination of AB works better than both A, B, and C)?

Table 2.

Relative sample sizes* required in the designs considered

| Design | Questions that can be adequately addressed | Sample size per arm | Overall sample size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two separate two-arm trials A vs C and B vs C† | Is A effective? | n | 4n |

| Is B effective? | |||

| Three-arm trial (randomly assigning to A, B, and C) powered for (no multiplicity adjustment)‡ | Is A effective? | n | 3n |

| Is B effective? | |||

| Factorial analysis of 2 × 2 design: factorial randomization powered for pooled analysis (no multiplicity adjustment)‡ | Is A effective? | n/2 | 2n |

| Is B effective? | |||

| (requires no interaction) | |||

| Factorial randomization powered for comparing each experimental arm with the control arm C (no multiplicity adjustment; this design does not address goal 2)‡ | Is A effective? | n | 4n |

| Is B effective? | |||

| Is AB better than C? | |||

| Factorial randomization powered for Bonferroni adjustment for the 5 pairwise comparisons | Is A effective? | 1.42 × n | 4 × (1.42 × n) |

| Is B effective? | |||

| Is AB effective? | |||

| Factorial randomization powered for the two-stage design (Korn etal., 2016 [10]) | Is A effective? | 1.29 × n | 4 × (1.29 × n) |

| Is B effective? | |||

| Is AB effective? | |||

| A vs B (limited power) |

Numbers represent sample sizes for normal or binary data or the number of events for time-to-event data. The designs in the last two rows assume 90% power with a .025 one-sided significance level.

It is assumed that two separate trials represent independent clinical experiments, and thus no multiple comparison adjustment is needed.

The sample sizes given in rows 2, 3, and 4 are not adjusted for the multiplicity; in contrast, the five-comparison Bonferroni and the two-stage procedures in rows 5 and 6 adjust for multiplicity. Assuming 90% power with a .025 one-sided significance level, when adjusted for the multiplicity of testing arms A and B in the same study, the sample sizes for the factorial and three-arm design in rows 2 and 3 need to be inflated by an additional factor of 1.18. When adjusted for multiplicity of comparing arms A, B, and AB vs C in the same study, the sample size for the design in row 4 needs to be inflated by an additional factor of 1.29. Whether to require multiplicity adjustment for the designs in rows 2 and 3 is debatable. For the factorial randomization powered for comparing each experimental arm approach (in row 4), multiplicity adjustment is needed in order to control the study-wise error rate because the experimental arms include overlapping components (5,7). Note, however, that regardless of this multiplicity adjustment, the approach in row 4 does not allow a statistically rigorous evaluation of goal 2.

If the goal is 1, then in the absence of reliable evidence of no interaction, the most efficient approach is to use a three-arm design in which patients are randomly assigned to arms A, B, and C (where arm C represents an appropriate comparator for both A and B) with the study having sufficient sample size to detect the desired effect for each of the two experimental vs control-arm comparisons. This requires 25% less patients than performing two separate trial analyses (row 2 vs row 1 of Table 2). While the three-arm design requires 50% more patients than a factorial design sized to use a factorial analysis (row 2 vs row 3 of Table 2), the three-arm design allows a reliable assessment of the study goal regardless of whether or not there is an interaction. Note that both the factorial and the three-arm design generally do not adjust for multiplicity of conducting two independent evaluations in one study; this is a subject for debate (2,4,5).

In many oncology settings, in addition to the individual efficacy of treatments A and B (vs control), it is of interest to evaluate the efficacy of their combination, that is, to determine whether combining A and B (AB) improves the outcome relative to each treatment alone (goal 2). As AB is not evaluated in the three-arm (A, B, and C) design, one needs to use a 2 × 2 factorial treatment assignment. One possible approach for designing such a trial is to base the primary analysis on comparing each of the three experimental arms (A, B, and AB) vs the control arm (and sizing the study to have sufficient statistical power for each of the three comparisons, row 4 of Table 2). A trial with a factorial design that used this approach is the STAMPEDE trial (6). However, this method does not formally address whether AB is better than either A or B (or better than the best of A, B, and C). Without reliable evidence that the combination improves outcome relative to each experimental treatment alone, recommending AB over A and B (as a part of goal 2) based on AB being better than C could be problematic.

A simple analysis approach that allows assessment of the combination therapy compared with the single agents specifies five primary comparisons (A vs C, B vs C, AB vs C, AB vs A, and AB vs B) and uses a five-comparison Bonferroni procedure (8) to adjust for the five tests. For example, for a design with an overall study-wise error rate of .025, each primary comparison is performed at the .005 (.025/5) statistical significance level. This was the analysis approach used in the SELECT trial (9). In this procedure, AB is recommended if all the AB vs C, AB vs A, and AB vs B comparisons are statistically significant (ie, demonstrating that AB is better than the best of A, B, and C). Adequately powering a study with the five-comparison Bonferroni procedure leads to increased required sample size as compared with a factorial analysis (row 5 vs row 3 of Table 2), but does not require the no-interaction assumption.

Although the five-comparison Bonferroni procedure rigorously addresses the clinical questions of goal 2, in the factorial treatment-assignment setting, the procedure can be improved upon by taking advantage of the natural hierarchy in the preference between the study arms: 1) if the experimental arms A and B are no better than the standard treatment C, then arm C is preferred, and 2) if the combination arm AB is no better than arm A (or B), then A (or B) is preferred. This hierarchy allows sequential testing of the study questions (as opposed to the simultaneous evaluation in the Bonferroni procedure) with improved statistical efficiency in a two-stage procedure (see the Supplementary Materials, available online, for details) (10). This strategy requires smaller samples size than the five-comparison Bonferroni procedure (row 6 vs row 5 of Table 2). Furthermore, the procedure also allows for a formal comparison of arms A and B, albeit with limited power (10).

In addition to the three strategies for nonfactorial analysis of factorial designs described above, some studies use a test for interaction (formally or informally) to decide whether to perform a pooled factorial analysis or a comparison of the individual arms (as was formally done in three studies in our survey). This strategy, however, has poor statistical properties (2) because these trials are typically sized for a factorial (pooled) analysis and thus 1) have insufficient power to detect an interaction and 2) generally have insufficient power for the individual arm comparisons (2,11). Note that none of the three studies that used this strategy in our survey were powered to detect meaningful interaction effects. (Employing a Bayesian approach, Simon and Freedman [12] suggest increasing the sample size by 30% to account for possible interaction.)

Examples

We illustrate the issues involved in analyzing factorial trial designs by considering the five-comparison Bonferroni procedure and the two-stage procedure discussed above for three of the trials identified in our factorial design survey. These re-analyses are used solely to illustrate the statistical issues in the analysis of factorial trial data and are not meant to suggest that the study investigators used inappropriate analyses.

Example 1

E1199, conducted by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, used a factorial trial design to evaluate docetaxel vs paclitaxel and a weekly vs an every-three-week schedule as adjuvant treatment for stage II/III breast cancer with the primary end point of disease-free survival (13,14). Patients were randomly assigned to arm C (paclitaxel every three weeks), arm A (weekly paclitaxel), arm B (docetaxel every three weeks), and arm AB (weekly docetaxel). The design specified a factorial analysis, using a two-sided .05 statistical significance level for each of the two primary factorial comparisons. If either of the primary factorial comparisons was statistically significant, then the design specified a comparison of each of the three experimental arms with the control arm using a .017 two-sided statistical significance level. The five-year disease-free survival rates for the four treatment arms were 76.9% (C), 81.5% (A), 81.2% (B), and 77.6% (AB). Neither of the primary factorial comparisons was statistically significant. However, as was noted by the investigators, the pooled factorial analysis was made uninterpretable by the presence of an interaction (Pinteraction = .003). Consequently, the investigators (appropriately, under the circumstances) performed an ad hoc analysis to compare the individual experimental arms with arm C and concluded that weekly paclitaxel (A) improves disease-free survival as compared with paclitaxel every three weeks (C).

The results of individual arm comparisons are given in Supplementary Table 1 (available online). When applied to these data, the five-comparison Bonferroni approach and the two-stage procedure allow the statistically rigorous conclusion (at the overall α= .025 level) that weekly paclitaxel (A) is superior to paclitaxel every three weeks (C). Further follow-up of this trial confirmed this result (14).

Example 2

CALGB 40603, conducted by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B, used a factorial trial design that compared bevacizumab vs no bevacizumab with carboplatin vs no carboplatin as added to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (15). Patients were randomly assigned to arm C (standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy), arm A (standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy + bevacizumab), arm B (standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy + carboplatin), and arm AB (standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy + carboplatin + bevacizumab). A factorial analysis was specified, with the primary end point being pathologic complete response rate (pCR). The primary factorial analysis showed marginal pCR rates of 60% vs 46% (one-sided P = .0018) for carboplatin vs no carboplatin and marginal rates of 59% vs 48% (one-sided P = .0089) for bevacizumab vs no bevacizumab. The individual arm response rates were 42%, 50%, 53%, and 67% for arms C, A, B, and AB, respectively; the report concluded that addition of either carboplatin or bevacizumab improved pCR rates (15).

The results of individual arm comparisons are given in Supplementary Table 2 (available online). The five-comparison Bonferroni procedure (at overall one-sided α= .025) allows one to conclude that the addition of carboplatin + bevacizumab is better than standard of care (arm AB vs C adjusted P = .005) and better than carboplatin (arm AB vs A adjusted P = .03). Using the two-stage procedure (at overall one-sided α= .025), carboplatin + bevacizumab is shown to be statistically significantly better than the standard of care (arm AB vs C adjusted P = .003). Furthermore, carboplatin + bevacizumab is shown to be statistically significantly better than all other study arms including the bevacizumab arm (arm AB vs best of [A, B, C] adjusted P = .024). Therefore, unlike the five-comparison Bonferroni approach or the factorial-analysis approach, the two-stage procedure allows a statistically rigorous recommendation of AB as the best of the four arms in this setting.

Example 3

AALL0232, conducted by the Children’s Oncology Group, used a factorial design to test whether dexamethasone is better than prednisone and whether high-dose methotrexate is better than the Capizzi methotrexate regimen in children with high-risk B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (16). Patients were randomly assigned to receive arm C (prednisone + Capizi methotrexate), arm A (dexamethasone + Capizi methotrexate), arm B (prednisone + high-dose methotrexate), or arm AB (dexamethasone + high-dose methotrexate). The trial was designed using a factorial analysis with the primary end point of event-free survival (EFS). An early interim analysis demonstrated the superiority of high-dose methotrexate over Capozi-methotrexate. However, because of the observed interaction between the corticosteroid and methotrexate regimen questions (two-sided P = .048), the final report considered individual study-arm outcomes: the five-year EFS rates in arms C, A, B, and AB were 82.1%, 83.2%, 80.8%, and 91.2%, respectively. Using the five-comparison Bonferroni procedure, one can show that dexamethasone + high-dose methotrexate (arm AB) is superior to the arms C, A, and B, with adjusted P values of .008, .019, and .0135, respectively (where a P value of .019 can be considered to represent the significance of the comparison of AB with the best of C, A, and B) (Supplementary Table 3, available online). Using the two-stage procedure, one can conclude superiority of dexamethasone + high-dose methotrexate to the other arms, with an adjusted P value of .0057 (Supplementary Table 3, available online). Therefore, both the five-comparison Bonferroni and two-stage procedures allow a statistically rigorous recommendation of arm AB, a much stronger conclusion than the factorial analysis.

Discussion

In oncology, a statistical interaction between two cancer therapies (a difference in the therapeutic effect of one therapy depending on whether or not it is administered in combination with the other therapy) is not uncommon; it may arise with or without the presence of a biologic interaction between the therapies. The presence of a statistical interaction compromises the ability of a factorial trial to provide rigorous evidence if the trial is designed using a factorial analysis. In the context of evaluating new cancer therapies, justifying the no-interaction assumption could be difficult. (Note that the no-interaction assumption is sometimes reasonable in certain prevention settings where treatment toxicity is negligible and the probability of each intervention working is low, or in some cancer-control trials where the treatments target unrelated quality-of-life outcomes.) Our review of recently completed trials with factorial designs suggests that the vast majority of trials are designed with a factorial analysis, thus explicitly or implicitly relying on the no-interaction assumption (an approach that leads to uninterpretable results if an interaction is present). Note that regardless of the assumptions about interactions made at the design stage and whether an interaction was observed after the study was completed, we recommend that the study should always report the main outcome(s) by arm to allow clear interpretation of the study results by the clinical community.

From the clinical trial design perspective, it is useful to note that the 2 × 2 factorial design is a special case of a general class of four-arm study designs that involve randomly assigning patients between: 1) the standard treatment D, 2) the experimental treatment A, 3) the experimental treatment B, and 4) the combination AB. This general design class includes trials where D is an active treatment that is not included in other arms. An example is given by the PERCY QUATRO trial (17), where patients with metastatic renal carcinoma were randomly assigned to receive: arm D (medroxyprogesterone), arm A (interferon alfa), arm B (interleukin 2), or arm AB (interferon alpha + interleukin 2). In such designs, the treatment assignment is not factorial and thus a factorial (pooled) analysis is not valid even in the absence of interaction. However, the five-comparison Bonferroni procedure and the two-stage procedure can still be applied.

In conclusion, while factorial 2 × 2 designs can be an efficient tool for developing new therapies, their use and analysis should be considered carefully. With infrequent exceptions, the no-interaction assumption will not be justified at the design stage. Therefore, if one is focused on an independent assessment of two treatments in a single RCT (and assessment of the treatment combination is not of interest), then the three-arm design would provide a simple and efficient evaluation by comparing each experimental arm with a common control without relying on the no-interaction assumption. On the other hand, if assessment of the combination of the two experimental arms is also of interest (but fully-powering the trial to test for a meaningful interaction is not feasible), then one needs to use an adequately powered 2 × 2 factorial arm assignment with an analysis strategy that can provide a statistically rigorous evaluation of the individual arms, such as the five-comparison Bonferroni or the two-stage procedure.

Notes

This manuscript was prepared using data from Datasets NCT00075725-D1 from the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) Data Archive of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) NCTN. Data were originally collected from clinical trial NCT number NCT00075725, “Dexamethasone Compared With Prednisone During Induction Therapy and MTX With or Without Leucovorin During Maintenance Therapy in Treating Patients With Newly Diagnosed High-Risk Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.” All analyses and conclusions in this manuscript are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the clinical trial investigators, the NCTN, or the NCI.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. McAlister FA, Straus SE, Sackett DL.. Analysis and reporting of factorial trials. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2545–2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green S, Liu PY, O’Sullivan J.. Factorial design considerations. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(16):3424–3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peterson B, George SL.. Sample size requirements and length of study of testing interaction in a 2 x k factorial design when time-to-failure is the outcome. Control Clin Trials. 1993;14(6):511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Byar DP, Piantadosi S.. Factorial designs for randomized clinical trials. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69(10):1055–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freidlin B, Korn EL, Gray R, et al. Multi-arm clinical trials of new agents: Some design considerations. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(14):4368–4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sydes MR, Parmar MK, James ND, et al. Issues in applying multi-arm multi-stage methodology to a clinical trial in prostate cancer: The MRC STAMPEDE trial. Trials. 2009;10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wason JMS, Stecher L, Mander AP.. Correcting for multiple-testing in multi-arm trials: Is it necessary and it is done? Trials. 2014;15:364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1998;75(4):800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klein EA, Thompson IM Jr, Tangen CM, et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2011;306(14):1549–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Korn EL, Freidlin B.. Non-factorial analyses of two-by-two factorial trial designs. Clin Trials. 2016;13(6):651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brittain E, Wittes J.. Factorial designs in clinical trials: The effects of non-compliance and subadditivity. Stat Med. 1989;8(2):161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Simon R, Freedman LS.. Bayesian design and analysis of two x two factorial clinical trials. Biometrics. 1997;53(2):456–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sparano JA, Wang M, Martino S, et al. Weekly paclitaxel in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N Eng J Med. 2008;358(16):1663–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sparano JA, Zhao F, Martino S, et al. Long-term follow-up of the E1199 phase III trial evaluating the role of taxane and schedule in operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(21):2353–2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sikov WM, Berry DA, Perou CM, et al. Impact of the addition of carboplatin and/or bevacizumab to neoadjuvant once-per-week paclitaxel followed by dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide on pathologic complete response rates in stage II to III triple-negative breast cancer: CALGB 40603 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(1):13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Larsen EC, Devidas M, Chen S, et al. Dexamethasone and high-dose methotrexate improve outcome for children and young adults with high-risk B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from Children's Oncology Group Study AALL0232. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20):2380–2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Negrier S, Perol D, Ravaud A, et al. Medroxyprogesterone, interferon alfa-2a, interleukin 2, or combination of both cytokines in patients with metastatic renal carcinoma of intermediate prognosis: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2007;110(11):2468–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.