Abstract

Background: The first generation CDK2/7/9 inhibitor seliciclib (CYC202) causes multipolar anaphase and apoptosis in lung cancer cells with supernumerary centrosomes (known as anaphase catastrophe). We investigated a new and potent CDK2/9 inhibitor, CCT68127 (Cyclacel).

Methods: CCT68127 was studied in lung cancer cells (three murine and five human) and control murine pulmonary epithelial and human immortalized bronchial epithelial cells. Robotic CCT68127 cell-based proliferation screens were used. Cells undergoing multipolar anaphase and inhibited centrosome clustering were scored. Reverse phase protein arrays (RPPAs) assessed CCT68127 effects on signaling pathways. The function of PEA15, a growth regulator highlighted by RPPAs, was analyzed. Syngeneic murine lung cancer xenografts (n = 4/group) determined CCT68127 effects on tumorigenicity and circulating tumor cell levels. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results: CCT68127 inhibited growth up to 88.5% (SD = 6.4%, P < .003) at 1 μM, induced apoptosis up to 42.6% (SD = 5.5%, P < .001) at 2 μM, and caused G1 or G2/M arrest in lung cancer cells with minimal effects on control cells (growth inhibition at 1 μM: 10.6%, SD = 3.6%, P = .32; apoptosis at 2 μM: 8.2%, SD = 1.0%, P = .22). A robotic screen found that lung cancer cells with KRAS mutation were particularly sensitive to CCT68127 (P = .02 for IC50). CCT68127 inhibited supernumerary centrosome clustering and caused anaphase catastrophe by 14.1% (SD = 3.6%, P < .009 at 1 μM). CCT68127 reduced PEA15 phosphorylation by 70% (SD = 3.0%, P = .003). The gain of PEA15 expression antagonized and its loss enhanced CCT68127-mediated growth inhibition. CCT68127 reduced lung cancer growth in vivo (P < .001) and circulating tumor cells (P = .004). Findings were confirmed with another CDK2/9 inhibitor, CYC065.

Conclusions: Next-generation CDK2/9 inhibition elicits marked antineoplastic effects in lung cancer via anaphase catastrophe and reduced PEA15 phosphorylation.

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related mortality (1–3). Despite current treatments, the five-year survival rate of lung cancer is only approximately 17% (1–3). Innovative ways to treat or prevent lung cancer are needed.

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) form complexes with their cyclin partners; these complexes regulate cell cycle progression (4,5). CDK2 and its partner, cyclin E, promote DNA duplication and orchestrate the G1 to S cell cycle transition by phosphorylating retinoblastoma protein (6). The CDK2-cyclin E complex is deregulated in pulmonary dysplasia and cancer (7). Cyclin E overexpression is associated with unfavorable clinical outcome (8). Consistent with a role for cyclin E in lung carcinogenesis, engineered mouse models targeting cyclin E expression in the lung caused lung cancer formation that recapitulated human lung cancer features, including chromosomal instability (9,10).

Aneuploidy and chromosomal instability are hallmarks of cancer, and neoplastic cells often have supernumerary centrosomes (11). We previously reported that CDK2 inhibition by seliciclib (CYC202, Cyclacel) treatment altered clustering of supernumerary centrosomes and induced multipolar anaphases and apoptosis in lung cancer cells (12,13). This was called anaphase catastrophe (12,13). Fates of seliciclib-treated lung cancer cells were determined by live cell imaging that revealed that these cells succumbed to apoptosis after induced anaphase catastrophe (14). This study found that engaging anaphase catastrophe was a way to combat lung and other genetically unstable cancer cells with supernumerary centrosomes, sparing normal cells without supernumerary centrosomes. This could be exploited in the cancer clinic using an optimal CDK2 antagonist.

The centrosome protein CP110 is phosphorylated by CDK2 and was identified as a key mediator of CDK2 inhibitor-dependent anaphase catastrophe (14). We reported that KRAS mutant as compared with wild-type lung cancers expressed substantially lower CP110 levels that enhanced anaphase catastrophe levels after CDK2 inhibition (14,15). KRAS mutant lung cancer cells were particularly responsive to the first-generation CDK2/7/9 inhibitor seliciclib (12). The next-generation CDK2/9 inhibitor CCT68127 (Cyclacel) is more specific and selective than prior CDK2/9 inhibitors. The CCT68127 purine backbone modification augmented stability and CDK2/9 inhibition relative to seliciclib (16). CCT68127 has antiproliferative activity against ovarian and colon cancer cells (16).

In the current study, the antineoplastic activity of CCT68127 was explored in murine and human lung cancers. Our hypothesis was that this next-generation CDK2/9 inhibitor would elicit marked antineoplastic activity in lung cancer by triggering anaphase catastrophe. Effects on proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle distribution, anaphase catastrophe, in vivo tumorigenicity, and circulating tumor cells were determined. Downstream activity of CCT68127 on cell signaling pathways was interrogated by reverse phase protein arrays (RPPAs). Translational relevance was determined using lung cancer tissue arrays, robotic screens, and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA).

Methods

Chemicals and Cell Culture

CCT68127, CYC065, and seliciclib were from Cyclacel (Dundee, UK). Trametinib was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX). Murine lung cancer cell lines ED1, LKR13, and 393P were from lung cancers of wild-type cyclin E, KrasLA1/+, and KrasLA1/+ p53R172HΔG transgenic mice, respectively, and were authenticated as described (9,10,17–19). Human lung cancer cell lines H522, H1703, A549, Hop62, and H2122 as well as murine C10 pulmonary epithelial and human Beas-2B immortalized bronchial epithelial cells were purchased and authenticated by American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

In Vitro Assays

Proliferation assays, apoptosis assays, cell cycle analyses, washout assays, drug combination analyses, multipolar anaphase assays, and expression plasmids/siRNA experiments are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Reverse Phase Protein Arrays

Cell lysates were arrayed on nitrocellulose-coated slides and stained with 218 unique antibodies and analyzed, as before (20–22).

Immunoblot Analyses and Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Assays

Details are in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

Immunohistochemistry

Lung cancer arrays containing 235 surgically resected non–small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) were previously described (14). Correlative studies were approved by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all the patients. Lung cancer arrays were probed with a PEA15 antibody (AB 135694; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 1:100) using a Leica BOND-MAX automated stainer (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and detected using Leica Bond Polymer Refine Detection reagent. Antibody specificity was confirmed using a blocking peptide. Immunohistochemical scoring was by a pathologist unaware of clinical data.

In Vivo Experiments

KRAS mutant murine lung cancer 393P cells (19) were infected with luciferase lentivirus (Cellomics Technology, Halethorpe, MD) and selected with puromycin. 393P (1 x 106) stable transfectants were injected subcutaneously into six- to eight-week-old male immunocompetent 129S2/SVPasCrl mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Mice with palpable tumors were treated with 50 mg/kg of CCT68127 or vehicle (DMSO/water/HCl) daily for three weeks (five days on and two days off) by oral gavage following an Institutional Animal Care and Use–approved protocol (n = 4 per group). Body weights and tumor volumes were measured with tumor volume (V) calculated as V = (length x width2)/2. Bioluminescence imaging was by D-Luciferin (Gold Biotechnology, Olivette, MO) and IVIS Lumina (Xenogen, Alameda, CA) and Living Imaging software (Xenogen) under 2% isoflurane. Mice were euthanized, and tumors were excised and weighed. Circulating tumor cells were measured as before (23).

Statistical Analysis

For each in vitro experiment, cells were plated in triplicates and treated independently. The averages of the triplicates were calculated to represent the value of that experiment. Then, the entire experiment was repeated at least two more times for a total of three experiments. The data points shown displayed were based on the biomarker values from three independent experiments (n = 3). Analysis of variance was applied to compare the biomarker measure among different cell lines or among different drug concentrations. Differences between two groups were assessed by Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test. To control the overall type I error rate in addressing the multiple comparisons, Tukey’s method was used for all pairwise comparisons across cell lines or experimental conditions. Dunnett’s method was applied for comparing the result of different concentrations with the control (vehicle) group, as well as comparing PEA15-targeting siRNA effects with control siRNA. Tumor growth in vivo was analyzed using the mixed model analysis. Kaplan-Meier survivals were by the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were with SPSS Statistics software (version 23, SPSS, Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism software (version 6, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

CCT68127 Effects

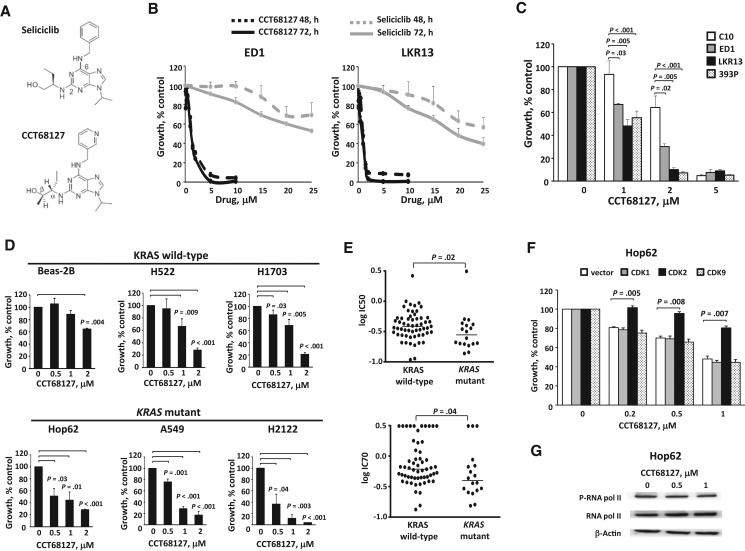

The design of CDK2/9 inhibitor CCT68127 was based on the purine template of the prior CDK2/7/9 inhibitor, seliciclib (Figure 1A) (16). CCT68127 has enhanced potency and selectivity for CDK2 and CDK9 compared with seliciclib (16). To compare CCT68127 and seliciclib activities, cell proliferation response curves for drug concentrations vs vehicle controls were examined in genetically defined murine lung cancer cell lines (ED1 and LKR13). Dose- and time-dependent growth suppression was observed, and as expected CCT68127 effects were more potent than seliciclib (IC50 of CCT68127 was < 1 uM, while the IC50 of seliciclib was > 25 uM) (Figure 1B). Murine lung cancer cells with mutant KRAS (LKR13 and 393P) appeared more responsive to CCT68127 than were ED1 lung cancer cells with wild-type KRAS expression (growth inhibition ± SD = 51.8% ± 5.8% in LKR13, 44.6% ± 5.8% in 393P, and 33.0% ± 1.0% in ED1 cells at 1 µM; 90.0% ± 1.6% in LKR13, 92.8% ± 1.5% in 393P, and 69.8% ± 2.4% in ED1 cells at 2 µM) (Figure 1C). In contrast, minimal growth inhibition was observed in C10 murine immortalized pulmonary epithelial cells treated at the lower (1 µM) dosage (growth inhibition ± SD = 6.7% ± 7.2% at 1 µM), implying preferential activity of CCT68127 against lung cancer cells (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Antiproliferative effects of CCT68127 against murine and human lung cancer cells. A) Structures of seliciclib and CCT68127. B) Dose-response treatments of seliciclib vs CCT68127 in murine (ED1 and LKR13) lung cancer cells. C) CCT68127 effects on growth of murine immortalized pulmonary epithelial cells (C10) and lung cancer cells (ED1, LKR13, and 393P). D) Effects of CCT68127 on growth of human immortalized bronchial epithelial (Beas-2B) and lung cancer (H522, H1703, Hop62, A549, and H2122) cells. E) Comparison of growth inhibition of CCT68127 in KRAS wild-type vs mutant lung cancer cells using a high-throughput screen of 75 human lung cancer cells. Each symbol displays an individual cell line. Bars represent median values. F) Consequences of engineered gain of individual CDK species expression on proliferation of CCT68127-treated Hop62 human lung cancer cells. G) Immunoblot analyses of phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II in Hop62 human lung cancer cells following CCT68127 treatment. Error bars are standard deviation. The P values were computed using t test with multiple comparison adjustment by Tukey's method (C and F) and Dunnett's method (D), and Mann-Whitney U test (E). All statistical tests were two-sided.

CCT68127 treatment effects were next examined in human lung cancer cells. Human lung cancer cells with mutant KRAS species (Hop62, A549, and H2122) were more sensitive than cells expressing wild-type KRAS (H522 and H1703) (growth inhibition ± SD = 55.7% ± 7.6% with P = .01 in Hop62, 71.5% ± 3.6% with P < .001 in A549, 88.5% ± 6.4% with P = .003 in H2122, 33.6% ± 6.6% with P = .009 in H522, and 31.6% ± 5.0% with P = .005 in H1703 cells at 1 µM). Beas-2B human immortalized bronchial epithelial cells were least sensitive to CCT68127 treatment (growth inhibition ± SD = 10.6% ± 3.6% at 1 µM, P = .32) (Figure 1D).

CCT68127 antiproliferative effects were scored with a high-throughput screening platform of 75 (57 KRAS wild-type and 18 KRAS mutant) human lung cancer cell lines. Cell lines with KRAS mutation were more sensitive to CCT68127 than KRAS wild-type cells (P = .02 for IC50 and P = .04 for IC70) (Figure 1E;Supplementary Table 1, available online).

When CDK1, CDK2, or CDK9 was transfected individually, only CDK2 expression antagonized CCT68127 effects in the lung cancer cells (Figure 1F;Supplementary Figure 1A, available online). Additionally, phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II, a target of CDK9, was not affected by CCT68127 (Figure 1G;Supplementary Figure 1B, available online). In combination with trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, CCT68127 showed synergistic or at least additive effects based on the MacSynergy II method (Supplementary Figure 2, available online).

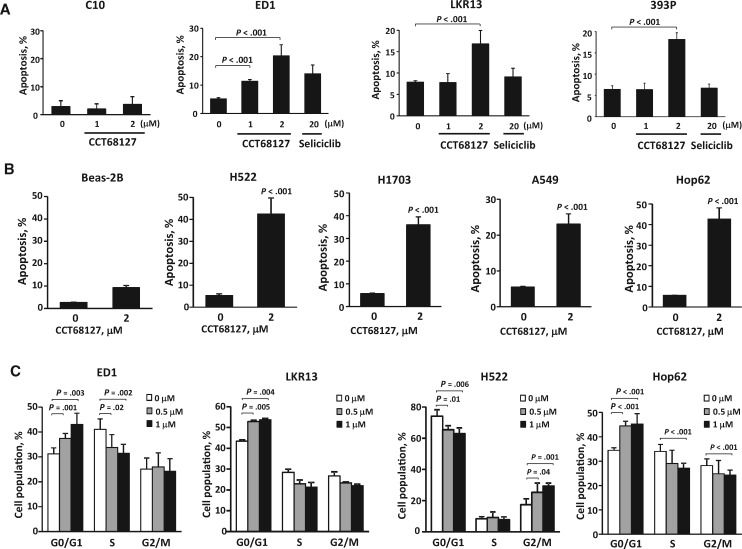

Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest by CCT68127

Apoptosis and cell cycle arrest induction after CCT68127 treatments of lung cancer cells were examined in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment effects occurred at much lower concentrations than with seliciclib (apoptosis ± SD 20.3% ± 3.9% with P < .001 in ED1, 16.8% ± 3.1% with P < .001 in LKR13, and 18.2% ± 1.5% with P < .001 in 393P cells at 2 µM of CCT68127; while 13.9% ± 3.1% with P = .12 in ED1, 9.1% ± 2.0% with P = .40 in LKR13, and 6.7% ± 0.9% with P = .58 in 393P cells at 20 µM of seliciclib). Apoptosis induction of C10 murine immortalized pulmonary epithelial cells was negligible (apoptosis ± SD = 2.0% ± 1.9% with P = .46 at 2 µM of CCT68127) (Figure 2A). Apoptosis induction by CCT68127 treatment was confirmed in human lung cancer cells without appreciable effects found in Beas-2B human immortalized bronchial epithelial cells (apoptosis ± SD = 42.4% ± 7.4% with P < .001 in H522, 36.0% ± 3.5% with P < .001 in H1703, 23.1% ± 2.8% with P < .001 in A549, 42.6% ± 5.5% with P < .001 in Hop62, and 8.2% ± 1.0% with P = .22 in Beas-2B cells at 2 µM) (Figure 2B). CCT68127 caused G1 arrest in ED1 (P = .003), LKR13 (P = .004), and Hop62 (P < .001) cells, and G2/M arrest only in H522 (P = .001) cells (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Apoptosis and cell cycle analysis in lung cancer cells after CCT68127 treatment. A) Percentages of apoptotic cells after CCT68127 treatment of murine immortalized pulmonary epithelial (C10) and lung cancer (ED1, LKR13, and 393P) cells. Apoptosis induction after seliciclib treatment is shown for murine lung cancer cells. B) Percentages of apoptotic cells after CCT68127 treatment of human immortalized bronchial epithelial (Beas-2B) and lung cancer (H522, H1703, A549, and Hop62) cells. C) Cell cycle analysis after CCT68127 treatment in murine (ED1 and LKR13) and human (H522 and Hop62) lung cancer cells. Error bars are standard deviation. The P values were computed using t test (B) with multiple comparison adjustment by Dunnett's method (A and C). All statistical tests were two-sided.

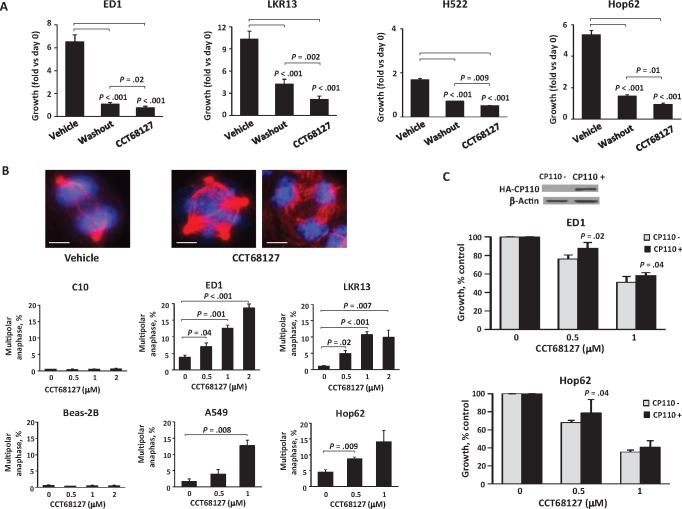

Anaphase Catastrophe by CCT68127

CCT68127 washout experiments were performed to learn if antineoplastic effects were reversible. Growth inhibition by CCT68127 treatment of lung cancer cells was only partially reversed after drug washout (P < .001) (Figure 3A). One possible engaged mechanism was induced anaphase catastrophe. To determine this, multipolar anaphases after CCT68127 or vehicle treatments were measured. CCT68127 readily caused multipolarity and anaphase catastrophe in both murine and human lung cancer cells, but not in bipolar control cells (C10 and Beas-2B) (multipolar anaphase ± SD = 13.6% ± 3.7% with P = .001 in ED1, 10.7% ± 1.0% with P < .001 in LKR13, 13.7% ± 1.7% with P = .008 in A549, and 14.1% ± 3.6% with P = .009 in Hop62 cells; while 0.4% ± 0.1% with P = .52 in C10 and 0.5% ± 0.2% with P = .55 in Beas-2B cells at 1 µM) (Figure 3B). Additionally, CCT68127 was found to inhibit clustering of supernumerary centrosomes (P < .001) (Supplementary Figure 3, A and B, available online) without affecting the incidence of supernumerary centrosomes (Supplementary Figure 3C, available online). Notably, when these cells were engineered with gain of expression of the centrosome protein CP110, a mediator of anaphase catastrophe after CDK2 antagonism (14,15), CCT68127 treatment effects were antagonized (P = .02 in ED1 and P = .04 in Hop62 cells at 0.5 µM) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Anaphase catastrophe in lung cancer cells after CCT68127 treatment. A) Comparison of CCT68127 effects on growth of lung cancer cells between vehicle controls, washout (CCT68127 washout after 48 hours’ treatment), and CCT68127 (continuously treated) groups. B) Percentages of cells undergoing multipolar anaphase after CCT68127 treatment in murine (ED1 and LKR13) and human (A549 and Hop62) lung cancer cells, and bipolar immortalized (C10 and Beas-2B) cells. Representative ED1 lung cancer cells are displayed in the upper panels with two spindle poles (vehicle control) and for those undergoing multipolar anaphases (four spindle poles in the middle panel and three spindle poles in the right panel) in the presence of CCT68127 treatment. The blue signal is DAPI staining, and the red signal is α-tubulin staining. Scale bars = 5 µm. C) Effects of engineered CP110 overexpression on growth inhibition by CCT68127 treatment of lung cancer cells. Error bars are standard deviation. The P values were computed using t test (C) with multiple comparison adjustment by the Tukey's method (A) and Dunnet's method (B). All statistical tests were two-sided.

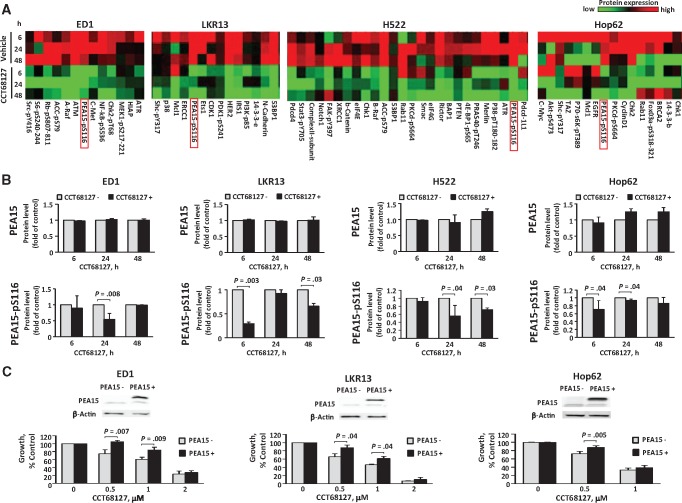

PEA15 and CCT68127 Effects

To uncover mechanisms engaged in CDK2/9 antagonism, CCT68127 treatment effects in lung cancer cells were comprehensively interrogated using RPPA. Expression profiles of 218 key growth-regulatory proteins were studied after 6, 24, and 48 hours of CCT68127 relative to vehicle treatments of murine (ED1 and LKR13) and human (H522 and Hop62) lung cancer cells (Supplementary Figure 4, available online). Attention focused on the cluster of proteins that showed marked repression after CCT68127 treatment (Figure 4A). Among these proteins, the multifunctional growth regulator PEA15 was highlighted. Levels of Ser116 phosphorylated PEA15 were reduced in all examined lung cancer cells by up to 70.0% ± 3.0% with a P value of .003, while its total expression was unaffected (Figures 4, A and B). This finding was independently confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Supplementary Figure 5, available online). When these cells were engineered with gain of PEA15 expression, growth inhibition by CCT68127 was antagonized (P = .007 in ED1, P = .04 in LKR13, and P = .005 in Hop62 cells at 0.5 µM) (Figure 4C), indicating the involvement of PEA15 in mediating CCT68127 antineoplastic effects.

Figure 4.

Involvement of PEA15 in CCT68127 antineoplastic effects in lung cancer cells. A) Heatmaps of protein expression profiles independently analyzed by RPPA in murine (ED1 and LKR13) and human (H522 and Hop62) lung cancer cells after vehicle or CCT68127 treatments. Clusters of proteins markedly downregulated by CCT68127 treatment are displayed. Complete heatmaps appear in Supplementary Figure 4 (available online). B) Quantifications of PEA15 and PEA15-pS116 protein levels by RPPA after CCT68127 vs vehicle treatments are shown with error bars representing standard deviation. C) Consequences of engineered gain of PEA15 expression on proliferation of CCT68127-treated lung cancer cells. Immunoblot analyses confirmed PEA15 overexpression in upper panels. Error bars show standard deviations. The P values were computed by t tests. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Effect of PEA15 Knockdown in Lung Cancer Cells

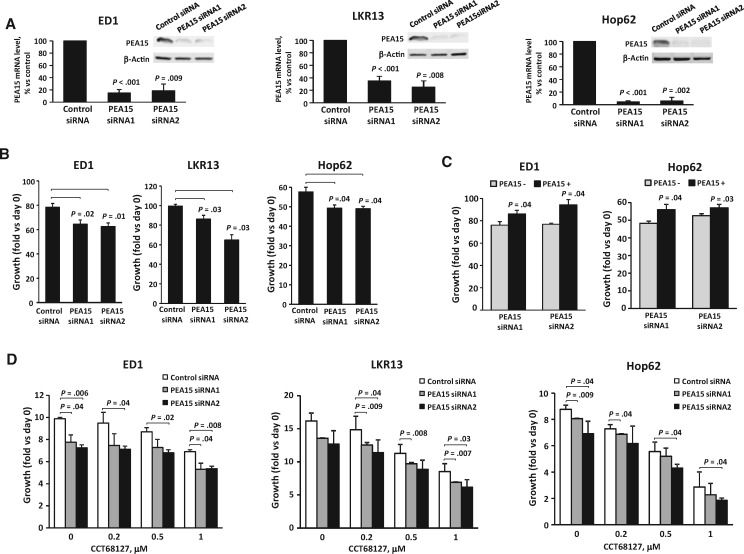

Direct effects of regulating PEA15 expression in lung cancer cells were examined using siRNAs targeting of PEA15. Independent knockdown of PEA15 by two different siRNAs was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and immunoblot assays in both murine and human lung cancer cells (Figure 5A). PEA15 knockdown repressed lung cancer cell growth by up to 35.4% (SD = 6.9%) with P = .03 (Figure 5B), which was reversed by restoring PEA15 expression (Figure 5C). PEA15 knockdown increased growth inhibition after CCT68127 treatment of lung cancer cells (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Effects of PEA15 knockdown in lung cancer cells. A) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and immunoblot analyses confirmed PEA15 knockdown. B) Consequences of PEA15 knockdown on growth of lung cancer cells. C) Restored PEA15 expression after PEA15 knockdown in lung cancer cells. Error bars represent standard deviation. D) Consequences of PEA15 knockdown on growth inhibition after CCT68127 treatment of lung cancer cells. Error bars represent the standard deviation. The P values were computed using t test with multiple comparison adjustment by Dunnett's method. All statistical tests were two-sided.

PEA15 Expression in Lung Cancers

PEA15 mRNA expression profiles in lung cancers were examined using TCGA data. Analyses revealed that PEA15 expression was statistically significantly lower in lung adenocarcinomas (ADs; P < .001) and lung squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs; P < .001) compared with normal lung tissues (Figure 6A). TCGA data established that PEA15 mRNA expression was reduced in the majority of different malignant vs normal tissues, including those of lung origin (Supplementary Figure 6, available online).

Figure 6.

PEA15 expression in human lung cancer cases. A) Comparison of PEA15 mRNA expression between normal (N) and malignant (T) lung tissues in lung adenocarcinoma (AD), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) lung cancers in the The Cancer Genome Atlas database (n = 59 for N, 517 for T in AD, and 51 for N, 501 for T in SCC). Each symbol represents a single case. Bars represent median values. B) PEA15 expression in normal and malignant lung tissues. Representative PEA15 immunostaining of lung cancers and adjacent normal lung tissues are in the upper panels, and PEA15 immunohistochemical staining of T and N are compared in the lower panels. Scale bars = 200 µm. C) Association between PEA15 immunohistochemical expression and stage. D) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival between human lung cancer cases stratified by PEA15 immunohistochemical expression (high, intermediate, and low). Error bars display standard deviation. The P values were computed using t test (A and B) with multiple comparison adjustment by Tukey’s method (C) and log-rank test (D). The trend test was also performed (C). All statistical tests were two-sided. AD = adenocarcinoma; N = normal; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; T = malignant.

PEA15 protein expression was investigated in 235 human lung cancers (142 ADs and 93 SCCs) by immunohistochemical analysis. Antibody specificity for PEA15 detection was confirmed using a blocking peptide (Supplementary Figure 7A, available online). Representative lung cancer PEA15 immunostaining appears in Supplementary Figure 7B (available online). When comparing lung cancers vs adjacent normal lung tissues, PEA15 immunohistochemical expression was lower in lung cancers (P = .02) (Figure 6B), in agreement with TCGA mRNA data (Figure 6A). Decreased PEA15 expression was associated with advanced stage (Ptrend= .02) (Figure 6C) and overall survival (P = .04 between the high-expression group and the intermediate-expression group, and P = .005 between high-expression group and low-expression group) (Figure 6D).

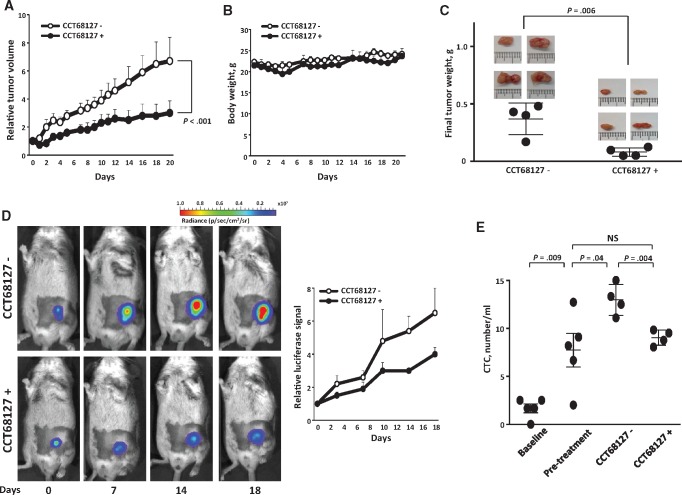

In Vivo CCT68127 Effects

In vivo CCT68127 effects on lung cancer growth were examined using a syngeneic murine lung cancer xenograft model. The 393P KRAS mutant murine lung cancer cell line was engineered to stably express luciferase. Cells were subcutaneously injected into immunocompetent syngeneic mice, which were subsequently treated with vehicle or 50 mg/kg of CCT68127 by oral gavage once daily for three weeks.

Tumor growth was analyzed using the mixed model analysis. Both the time effect and time by treatment interaction of tumor growth were statistically significant (P < 0.001), indicating that the tumor growth rate of the CCT68127-treated group was reduced as compared with the vehicle-treated control group (Figure 7A). There was no appreciable body weight loss, indicating that this agent was well tolerated at this displayed treatment dose (Figure 7B). Higher treatment dosages were associated with toxicity (data not shown). Excised tumors after completion of treatment were smaller in CCT68127-treated than in vehicle-treated mice (P = .006) (Figure 7C). Tumor burden was independently monitored via bioluminescent imaging. Representative images of vehicle vs CCT68127-treated mice are in Figure 7D. The increase in bioluminescence was inhibited in CCT68127-treated mice (Figure 7D), consistent with results from tumor volume measurements (Figure 7A). Circulating tumor cells were measured using a method that we reported (23). Compared with vehicle-treated mice, circulating tumor cells were decreased in CCT68127-treated mice (P = .004) to the same level as the pretreatment group (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

Antitumorigenic effects of CCT68127 treatments. A) Comparison of lung cancer growth in mice treated with vehicle or CCT68127. Day 0 is the treatment start date. B) Mouse body weights did not appreciably change during vehicle or CCT68127 treatments. Error bars are standard deviation. C) Comparison of tumor weights after treatments with vehicle or CCT68127. Each symbol represents a single mouse. Images of the excised tumors are shown. D) Comparison of bioluminescent signals of syngeneic lung cancers in mice treated with vehicle or CCT68127. Representative bioluminescence images of these mice are shown over time in the left panels. E) Comparison of circulating tumor cell (CTC) numbers within the different groups of mice. The baseline group is mice without tumor cell injections. The pretreatment group was injected with tumor cells subcutaneously, and their CTCs were analyzed before the treatment. CCT68127 negative (-) and CCT68127 positive (+) groups were injected with tumor cells subcutaneously, and CTCs were analyzed after completion of the independent treatments with vehicle or CCT68127, respectively. Bars display mean value in this panel. Error bars represent the standard deviation in all graphs. The P values were computed using the mixed model analysis (A) and t test (B) with multiple comparison adjustment by Tukey's method (E). All statistical tests were two-sided. CTC = circulating tumor cell.

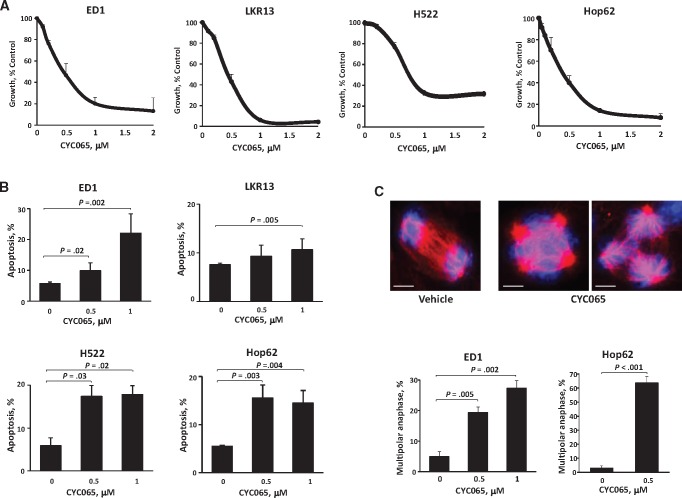

Antineoplastic Activity of Second CDK2/9 Inhibitor

To independently determine the translational relevance of these findings, antineoplastic activities of a clinical lead CDK2/9 inhibitor, CYC065, were evaluated. Substantial growth suppression and apoptosis followed CYC065 treatment of murine (ED1 and LKR13) and human (H522 and Hop62) lung cancer cells (IC50 ± SD = 0.45 ± 0.10 µM in ED1, 0.41 ± 0.06 µM in LKR13, 0.76 ± 0.03 µM in H522, and 0.37 ± 0.09 µM in Hop62 cells; apoptosis ± SD = 22.1% ± 6.3% with P = .002 in ED1, 10.7% ± 2.2% with P = .005 in LKR13, 17.9% ± 2.1% with P = .02 in H522, and 14.5% ± 2.6% with P = .004 in Hop62 cells at 1 µM) (Figure 8, A and B). CYC065 readily induced anaphase catastrophe (multipolar anaphase ± SD = 19.3% ± 1.9% with P = .005 in ED1 and 63.6% ± 4.5% with P < .001 in Hop62 cells at 0.5 µM) (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Antineoplastic activity of the CDK2/9 inhibitor CYC065. A) Dose-response curves for murine (ED1 and LKR13) and human (H522 and Hop62) lung cancer cells after CYC065 or vehicle treatments. B) Percentage of apoptotic cells after CYC065 treatment in murine (ED1 and LKR13) and human (H522 and Hop62) lung cancer cells. C) Percentages of cells undergoing multipolar anaphase after CYC065 or vehicle treatments of murine (ED1) and human (Hop62) lung cancer cells. The vehicle control lung cancer cell shown is bipolar, and in marked contrast the CYC065 treated cells are, respectively, shown with three (right panel) or four (middle panel) spindle poles. The blue signal is DAPI staining, and the red signal is α-tubulin staining. Scale bars = 5 µm. Error bars are standard deviation. The P values were computed using t test with multiple comparisons by Dunnet's method. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Discussion

This study reports that the next-generation CDK2/9 inhibitor CCT68127 has potent antineoplastic activity against both murine and human lung cancers and that its activity is more pronounced than the first-generation CDK2/7/9 inhibitor seliciclib. Antineoplastic effects of CCT68127 were antagonized by the engineered gain of CDK2, but not CDK1 or CDK9 expression, indicating that CCT68127 treatment effects were largely due to CDK2 inhibition, as is consistent with a prior report (16) showing that CCT68127 has highly selective inhibition against CDK2 as compared with other CDKs. Furthermore, a high-throughput screen using 75 human lung cancer cell lines revealed KRAS mutant lung cancer cells are more responsive to CCT68127 than were KRAS wild-type lung cancer cells. This has translational relevance because KRAS mutant lung cancers are an unmet medical need (24).

Interestingly, a synthetic lethal interaction between KRAS oncogenes and CDK4 is reported (25). The activity of CDK inhibitors in KRAS mutant lung cancers in the clinic will be worth exploring in future work. Another promising strategy to consider in KRAS mutant lung cancer is combination therapy (26). Of note, CCT68127 had synergistic or at least additive effects when combined with trametinib treatment in lung cancer cells. CDK4/6 inhibition was recently found to have antineoplastic activity in KRAS mutant lung cancer when combined with trametinib (27).

CCT68127 readily induced anaphase catastrophe, as did seliciclib and dinaciclib treatment, as we previously reported (12,28). Anaphase catastrophe occurs when cells with more than two centrosomes are prevented from appropriately clustering supernumerary centrosomes at cell mitosis, sparing normal bipolar cells that do not have supernumerary centrosomes (12,13). In the current study, anaphase catastrophe was not appreciably induced in control bipolar immortalized cells. Likewise, growth inhibition and apoptosis induction by CCT68127 treatment were also minimally observed in these studied cells. It is hypothesized that CCT68127 treatment preferentially affects chromosomally unstable tumor cells with supernumerary centrosomes and thereby spares normal bipolar cells and tissues from anaphase catastrophe or toxicity.

Comprehensive analysis of expressed protein changes by RPPA uncovered PEA15 phosphorylation at Ser116 as substantially reduced after CCT68127 treatment. Based on the reported consensus amino acid sequence of CDK substrates (29–31) and our bioinformatic analysis of the amino acid sequence of PEA15 using GPS 2.1 software (32), PEA15 was not highlighted as a direct CDK substrate (data not shown). Yet gain of PEA15 expression reduced growth inhibition despite low-dose CCT68127 treatment. Given this, PEA15 likely played as least an indirect role in exerting observed CCT68127 effects.

PEA15 regulates diverse cellular processes, and both tumor-suppressive and oncogenic activities are reported in different cancers (33–37). In the current study, PEA15 knockdown inhibited lung cancer cell growth, implicating it as an oncogenic species in this setting. It is notable that immunohistochemical analysis revealed that PEA15 expression was statistically significantly lower in lung cancers than in normal lung tissues. Also, reduced PEA15 expression was associated with advanced lung cancer stage and an unfavorable overall survival, indicating a potential tumor-suppressive role for PEA15. This dual nature of PEA15 is thought to depend on its phosphorylation state (33,38,39). When unphosphorylated, PEA15 binds ERK1/2 and is sequestered in the cytoplasm, preventing translocation into the nucleus (39–41). In contrast, PEA15 phosphorylation can release ERK1/2 into the nucleus (33,39,40). Upon phosphorylation, PEA15 binds Fas-associated death domain protein, inhibiting apoptosis (33). Changes in the phosphorylation state can turn PEA15 from a tumor suppressor to an oncogene (33,38,39,41). Future work should determine the precise role of PEA15 in lung cancer biology.

Substantial CCT68127 in vivo antineoplastic effects against lung cancer were uncovered. Using a xenograft of KRAS mutant murine lung cancer, modeling a clinical unmet need, CCT68127 exerted marked reduction of tumorigenicity as well as circulating tumor cells without conferring appreciable toxicity in mice at the displayed dosage. These data provide a strong rationale for clinical testing of a potent CDK2/9 inhibitor in lung cancer patients whose tumors harbor KRAS mutations. Because circulating tumor cells can predict metastasis (42), CCT68127-mediated reduction of circulating tumor cells implicates a role for this agent in preventing lung cancer metastasis.

The current study does have some limitations. For instance, when mice were treated with higher CCT68127 dosages (75 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg), they did not tolerate those dosages. Such toxicity might limit clinical efficacy of CCT68127. It is notable that a different next-generation CDK2/9 inhibitor (CYC065) was also examined in this study. This agent may exhibit greater efficacy along with reduced toxicity in the clinic than CCT68127. In this regard, this agent was particularly potent in inducing anaphase catastrophe. Future work should include testing of CYC065 in the cancer clinic.

In summary, the CDK2/9 inhibitor CCT68127 exerts prominent antitumor activity against lung cancer through mechanisms engaging anaphase catastrophe and reduced PEA15 phosphorylation. Clinical relevance of CCT68127 mechanisms of action was confirmed by studies of the related clinical CDK2/9 inhibitor CYC065. Further clinical investigation of an optimal CDK2/9 inhibitor is warranted, especially in lung cancer cases with KRAS mutation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants R01-CA087546 (ED) and R01-CA190722 (ED), a Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation Award (ED), UT-STARs award (ED), American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professorship (ED), and by generous philanthropic contributions to The University of Texas MD Anderson Lung Moon Shot Program.

Notes

The study funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We thank Drs. Uma Giri and Shaohua Peng at MD Anderson Cancer Center for assistance in the high-throughput screen of CCT68127 in lung cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Islami F, Torre LA, Jemal A.. Global trends of lung cancer mortality and smoking prevalence. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;44:327–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;652:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, et al. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends-an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;251:16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shapiro GI. Cyclin-dependent kinase pathways as targets for cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;2411:1770–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freemantle SJ, Liu X, Feng Q, et al. Cyclin degradation for cancer therapy and chemoprevention. J Cell Biochem. 2007;1024:869–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harbour JW, Luo RX, Dei Santi A, et al. Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell. 1999;986:859–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lonardo F, Rusch V, Langenfeld J, et al. Overexpression of cyclins D1 and E is frequent in bronchial preneoplasia and precedes squamous cell carcinoma development. Cancer Res. 1999;5910:2470–2476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fukuse T, Hirata T, Naiki H, et al. Prognostic significance of cyclin E overexpression in resected non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;602:242–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ma Y, Fiering S, Black C, et al. Transgenic cyclin E triggers dysplasia and multiple pulmonary adenocarcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;10410:4089–4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freemantle SJ, Dmitrovsky E.. Cyclin E transgenic mice: Discovery tools for lung cancer biology, therapy, and prevention. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;312:1513–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA.. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;1445:646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Galimberti F, Thompson SL, Liu X, et al. Targeting the cyclin E-Cdk-2 complex represses lung cancer growth by triggering anaphase catastrophe. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;161:109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Galimberti F, Thompson SL, Ravi S, et al. Anaphase catastrophe is a target for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;176:1218–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hu S, Danilov AV, Godek K, et al. CDK2 inhibition causes anaphase catastrophe in lung cancer through the centrosomal protein CP110. Cancer Res. 2015;7510:2029–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hu S, Lu Y, Orr B, et al. Specific CP110 phosphorylation sites mediate anaphase catastrophe after CDK2 inhibition: Evidence for cooperation with USP33 knockdown. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;1411:2576–2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilson SC, Atrash B, Barlow C, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of 6-pyridylmethylaminopurines as CDK inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;1922:6949–6965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu X, Sempere LF, Ouyang H, et al. MicroRNA-31 functions as an oncogenic microRNA in mouse and human lung cancer cells by repressing specific tumor suppressors. J Clin Invest. 2010;1204:1298–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wislez M, Fujimoto N, Izzo JG, et al. High expression of ligands for chemokine receptor CXCR2 in alveolar epithelial neoplasia induced by oncogenic kras. Cancer Res. 2006;668:4198–4207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gibbons DL, Lin W, Creighton CJ, et al. Contextual extracellular cues promote tumor cell EMT and metastasis by regulating miR-200 family expression. Genes Dev. 2009;2318:2140–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheng KW, Lu Y, Mills GB.. Assay of Rab25 function in ovarian and breast cancers. Methods Enzymol. 2005;403:202–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tibes R, Qiu Y, Lu Y, et al. Reverse phase protein array: Validation of a novel proteomic technology and utility for analysis of primary leukemia specimens and hematopoietic stem cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;510:2512–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iadevaia S, Lu Y, Morales FC, et al. Identification of optimal drug combinations targeting cellular networks: Integrating phospho-proteomics and computational network analysis. Cancer Res. 2010;7017:6704–6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Myung JH, Roengvoraphoj M, Tam KA, et al. Effective capture of circulating tumor cells from a transgenic mouse lung cancer model using dendrimer surfaces immobilized with anti-EGFR. Anal Chem. 2015;8719:10096–10102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts PJ, Stinchcombe TE.. KRAS mutation: Should we test for it, and does it matter? J Clin Oncol. 2013;318:1112–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Puyol M, Martin A, Dubus P, et al. A synthetic lethal interaction between K-Ras oncogenes and Cdk4 unveils a therapeutic strategy for non-small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2010;181:63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dieltlein F, Kalb B, Jokic M, et al. A synergistic interaction between Chk1- and MK2 inhibitors in KRAS mutant cancer. Cell. 2015;1621:146–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tao Z, Le Blanc JM, Wang C, et al. Coadministration of trametinib and palbociclib radiosensitizes KRAS mutant non-small cell lung cancers in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;221:122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Danilov AV, Hu S, Orr B, et al. Dinaciclib induces anaphase catastrophe in lung cancer cells via inhibition of cyclin dependent kinases 1 and 2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;1511:2758–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang EJ, Begum R, Chait BT, et al. Prediction of cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation substrates. PLoS One. 2007;27:e656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chi Y, Welcker M, Hizli AA, et al. Identification of CDK2 substrates in human cell lysates. Genome Biol. 2008;910:R149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Errico A, Deshmukh K, Tanaka Y, et al. Identification of substrates for cyclin dependent kinases. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2010;501:375–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xue Y, Liu Z, Cao J, et al. GPS 2.1: Enhanced prediction of kinase-specific phosphorylation sites with an algorithm of motif length selection. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2011;243:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greig FH, Nixon GF.. Phosphoprotein enriched in astrocytes (PEA)-15: A potential therapeutic target in multiple disease states. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;1433:265–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stassi G, Garofalo M, Zerilli M, et al. PED mediates AKT-dependent chemoresistance in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;6515:6668–6675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Glading A, Koziol JA, Krueger J, et al. PEA-15 inhibits tumor cell invasion by binding to extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Cancer Res. 2007;674:1536–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eckert A, Bock BC, Tagscherer KE, et al. The PEA-15/PED protein protects glioblastoma cells from glucose deprivation-induced apoptosis via the ERK/MAP kinase pathway. Oncogene. 2008;278:1155–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Incoronato M, Garofalo M, Urso L, et al. miR-212 increases tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand sensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer by targeting the antiapoptotic protein PED. Cancer Res. 2010;709:3638–3646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sulzmaier F, Opoku-Ansah J, Ramos JW.. Phosphorylation is the switch that turns PEA-15 from tumor suppressor to tumor promoter. Small GTPases. 2012;33:173–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mace PD, Wallez Y, Egger MF, et al. Structure of ERK2 bound to PEA-15 reveals a mechanism for rapid release of activated MAPK. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shin M, Lee KE, Yang EG, et al. PEA-15 facilitates EGFR dephosphorylation via ERK sequestration at increased ER-PM contacts in TNBC cells. FEBS Lett. 2015;5899:1033–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Formstecher E, Ramos JW, Fauquet M, et al. PEA-15 mediates cytoplasmic sequestration of ERK MAP kinase. Dev Cell. 2001;12:239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Massague J, Obenauf AC.. Metastatic colonization by circulating tumour cells. Nature. 2016;5297586:298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.